Candice Ransom's Blog, page 6

August 24, 2015

Summer Reading

Though summer is fast coming to an end, I’m cramming in as many thrillers and other “beach” reads as I can. At the beginning of this month, Bookology published a short essay of mine about children’s summer reading. I’m one of the magazine’s many contributors, happy to be among writers like Avi, Virginia Euwer Wolff, and Heather Vogel Frederick. Here is my piece:

Every summer I wish I was ten again, the perfect age for the perfect season. At that age I was at the height of my childhood powers. And as a reader, books couldn’t be thrust into my hands fast enough.

Every morning I’d eat a bowl of Rice Krispies, with my book at the table (my mother wouldn’t let me do this at supper, though I often kept my library book open on the seat of the chair beside mine). Then I’d go out to my tree house to watch birds and read the day into being. Whatever I was reading—fiction or nonfiction—shaped my daily experiences. I longed to live in books.

At ten, I had mastered writing and drawing to the degree that I was comfortable moving back and forth between words and images. With pencil, paper, and crayons, I could slip into the world beyond the printed page. I “continued” the story in the book, or drew pictures, sometimes copying the illustrations.

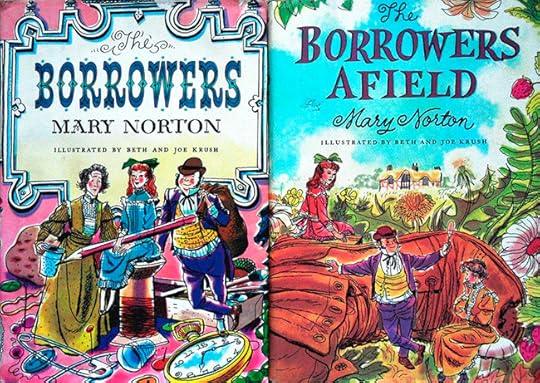

I loved the reckless, sketchy lines of Beth and Joe Krush’s drawings in The Borrowers. And I drew precise, tiny black cats like the ones Eric Blegvad often included in books he illustrated, like The Diamond in the Window, and Superstitious? Here’s Why!

Books led me to places beyond my small Virginia landscape. After finishing The Talking Tree, a novel about Pacific Northwest Native Americans, I was desperate to make my own totem pole. I glued three empty thread spools together and tried to etch a stylized raven, wolf, and beaver with the pointed end of a nail file that kept skidding off the smooth wooden surface.

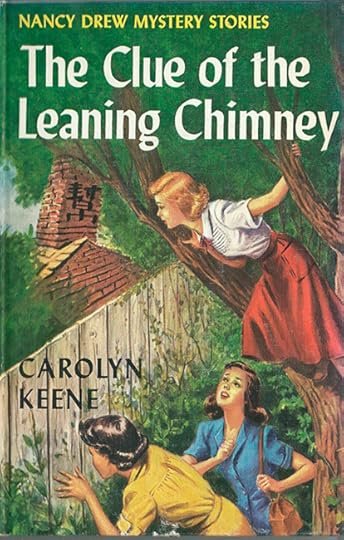

My cousins got roped into acting out a Nancy Drew story. The Mystery of the Leaning Chimney gave me the bright idea of burying my mother’s sake cup, brought back by my uncle after WWII, in our back yard. When my cousins rolled up, I ran to meet their station wagon.

“Mama’s valuable foreign vase has been stolen!” I exclaimed, showing the boys the sinister-sounding note I’d written.

“Aw, you wrote that,” Eugene said, recognizing my handwriting.

“No, really, it’s from the vase stealer!” I was shocked at his unwillingness to suspend disbelief, but undeterred. I dragged them all over the yard, digging holes until I “stumbled” on the buried cup.

What made that summer special was the freedom to read. I read during the school year, of course, and even in class when I was supposed to be working on fractions, but pleasure reading time was squished to weekend afternoons and bedtime. Summer, however, was one Great Big Reading Fest.

Best of all, I wasn’t hobbled by a summer reading list. I grew up in an era in which teachers turned kids loose in June, glad not to clap eyes on them again until after Labor Day. Now many elementary schools ask students to read to prevent “Summer Slide.”

The random lists I checked offer a wide variety of books in a range of reading levels. But the reading list noose tightens in middle and high schools. Students are often required to read from a more specific list and write a paper.

In her recent Washington Post piece, educator Michelle Rhee admits her own childhood dislike of summer reading lists that included such titles as Anne of Green Gables and other books she trudged through with little interest. As a teacher, and later as chancellor of D.C. Public Schools, she recognized the value of summer reading programs. But she also believes students should choose their own books.

A few weeks ago, I wandered the nonfiction children’s section in our public library. A boy around ten sat cross-legged on the floor, a book on helicopters open in his lap. I guessed he had pulled the book from the shelf and plunked right down to read it.

“Mom!” he said. “You have to see this! It’s the most amazing thing in the world!”

It is the most amazing thing in the world to watch a child just the right age fall into a book of his choice. I hope that boy will keep that glorious part of his self always. Let books continue to guide him, pull him in, shape his day.

If you have a child, head to the library and don’t come out until you’re both carrying a big stack of books. If you don’t have any kids handy, go anyway and indulge in your old favorite children’s books, or new titles you haven’t had time to read. Labor Day is still two weeks away!

August 16, 2015

Making Magic

We heard their piping, excited voices as soon as we walked through the door. My friend Donna and I had planned a Friday morning pause between exercise and errands. After meeting at a downtown coffee shop to talk shop, we’d sandwich in a gallery-hop at Liberty Town Arts Center. And now there were kids. We exchanged glances of amused dismay.

Voices carried in the high-ceilinged old plumbing supply warehouse that housed studios and galleries. We followed the chatter upstairs.

At a table set up in the narrow hall, a painting class was in session. The kids looked up at us and I wondered if they were irritated at our intrusion. The little girls, all about six or seven, smiled bright as newly-minted pennies, then returned to their work.

As we edged past, one girl said to the others, “This is the magic time.” Yes, it is, I wanted to say.

Donna and I wandered through the beehive of studios. Finished paintings were propped against easels. Glazed pots lined shelves.

Jugs of brushes, baskets of half-squeezed oil tubes, and watercolor-daubed palettes covered taboret carts.

Some studios had inviting furniture and thickly-piled rugs. Crystal chandeliers made a classy contrast to open duct work. I longed to move in and play.

Studio paintings seemed at rest, content with the last brushstroke. Slightly musty air settled on my arms. I recognized that mid-August feeling, like riding the Ferris wheel when it pauses at the top and the whole world is spread out below.

Donna glanced at her watch. Time tugged at us.

Art, says Teller of Penn and Teller, is anything we do after the chores are done. My to-do list was depressingly long but I was grateful for this interlude. After steeping myself in paintings and pottery, I could face the hot sun and uninspiring stops along Route 3. Maybe save some of this day for some art-making of my own.

On our way out, we passed the children’s class again. The little girls smiled around lollipops, cheerful as a field of daisies. The whole world stretched out before them; time hung suspended between the taste of cherry and a splash of red paint.

I walked down the steps, remembering when I was forever-seven in always-August and I too made magic all day long.

One girl remarked to the girl sitting across from her, “Don’t you wish you were me?”

Yes, I wanted to say back. I do.

August 4, 2015

Missing: The Children of Summer

It was a place I often thought about. I located a lot of my imaginings in it. ~~ Wendell Berry

As I cruised through my neighborhood last Thursday afternoon, I felt like an extra in a Charlton Heston sci-fi movie, “Soylent Green,” perhaps, or maybe “The Omega Man.” When I left for Hollins University back in June, kids were always outside, playing soccer, drawing on sidewalks, tossing Frisbees, turning newly-learned cartwheels.

Now the streets were silent and empty. Bikes were flung in front yards as if their owners had been vaporized. Our cul-de-sac alone is home to seventeen kids of various ages, but not a single one was in sight. It wasn’t until Sunday evening, long after the sun had dipped over the treetops, but well before lightning bugs rose and sparked from the clover, that I saw my first child outside. She ran indoors as if ordered by martial law.

Yes, it’s another hot July in Virginia so everyone takes refuge in air-conditioned buildings. But it’s always hot in Virginia in July. The house I grew up in didn’t have a/c or even a fan, except for the window fan in the grownup’s bedroom and that was only switched on after dark. What did us kids do all day? We stayed outside. Being outdoors was preferable to being indoors because that’s where we became our summer selves.

For me and my town cousins, our summer selves swapped Classic comics under the big silver maple tree. We argued whether Kool-Aid or Cheer-Aid was better. We fed green grapes to the neighbor’s chickens. We ambled through the field behind the lumber yard, scouting killdeer nests. We slipped on moss-slicked mussels in Milford Mills Creek. We played Red Light, Green Light among fireflies. After our baths, fragrant with talcum powder, we lay across the bed to catch the faint breeze, watch the blinking radio tower and make ambitious plans for the next day.

At home, I claimed my own summer kingdom. In the woods, I rode a bouncy sapling over imaginary prairies. I built a fort out of a roll of chicken wire and a musty tarp. I read Nancy Drew, the yellow-back books, in my tree house. I played in the woods and fields alone and unsupervised. I was always (well, usually) within hollering distance. Once, I crossed a little red bridge arching over a creek that led to rustic Japanese-style buildings and an in-ground pool. I wandered around the strange camp, enchanted, then found my way home. I never located that camp again.

But it was okay. The camp, like the horse-tree, the chicken-wire fort, intrepid Nancy Drew, the back yard, the front yard, the sedge-y margin between garden and woods, all formed the place of my summers. And that place was mine by right. Woods and fields, any wild outdoor spaces, belong to children.

In her book A Country Called Childhood: Children and the Exuberant World, Jay Griffiths names nineteenth-century poet John Clare as the patron saint of childhood. “Clare writes of the land as if he were a belonging of the land, as if it owned him . . . his childhood belonged to that land and to its creatures; he knew them all and felt known in turn.” Making her case for nature-deficient children, Griffiths threads ribbons of Clare’s poetry about his childhood “lost in a wilderness of listening leaves,” “roaming about on rapture’s easy wing.”

Recently I stumbled on aerial photographs of the area where I grew up. With a click of the mouse, I peeled back layers and years, the same spot in 1979, in 1968, 1963, down to 1962, when I was ten. And there were my fields and woods, the strange camp, the holly tree in the front garden, even the hog pen. The location of a lifetime of imaginings. I touched the monitor glass, willing it to vanish so I could run barefoot in that grass again.

Over the decades I’ve watched as government, schools, and parents annexed the country of childhood. Driven by litigation and ever-increasing safety standards, communities and schools build playground equipment so tame—no angles, corners, or edges—that older kids become quickly bored. Recess has been chipped away or morphed into organized sports. The number of kids who walk to school—or walk anywhere—has dropped significantly since the 1970s.

When the kids in my neighborhood do play outside, they stay confined to their small front yards, or the cul-de-sac, almost always with a parent nearby. There is no chance for them to belong to a patch of asphalt, to be owned by a square of neatly-manicured lawn. Certainly no opportunity to slap together a fort from rusted chicken wire or discover a mysterious camp in the woods or feel known by birds and wild flowers.

Where are the children of summer today? They are holed up in their bedrooms in self-imposed curfew, watching TV or playing computer games or constructing Lego sets with detailed directions. Their freedom has been chiseled into a safe haven . . . or a cage.

Worse, they don’t even know what they are missing.

As a children’s writer, I’ve preferred to write realistic fiction about kids who sort themselves into pack hierarchies, explore, make up their own traditions and games, and rearrange the landscape to locate their imaginings, just as I did. These days I’m writing the same type of books, but they are fantasy.

At night when my mind idles, I think about the places that shaped my childhood and wonder what the children of summer today will remember when they are grown up.

June 28, 2015

“Go Where You Are Welcome”

The trees welcomed him. The bushes made way for him.

George Macdonald, The Golden Key

Years ago my career and I had a big falling out. I pouted for a while, then decided to leave children’s books and turn to writing adult mysteries. It was not an unfounded decision— seven of my books were canceled in one year, including a picture book at press. The reasons for the cancellations were varied, but most were due to mergers.

This was the mid-90s and mysteries were the Next Hot Thing, particularly cozies. I read several series and, like many people, figured I could do it too. I bought books on writing mysteries. I quit the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Children’s Book Guild of Washington, D.C. and joined Sisters in Crime.

At my first Sisters in Crime luncheon meeting, conversation was not about growing little children’s minds, but how to poison your husband without getting caught. Murder was fun! Why hadn’t I made the switch sooner? The salad course was served, a spiced apple ring on a lettuce leaf, garnished with parsley. And there, on top of my parsley sprig perched a bright green inch worm. He waved at me.

I looked around the table. No one else had worms in their salads. Was this an initiation? To prove worthy was I supposed to flick the worm onto my neighbor’s plate? Eat it? I didn’t know what to do. At children’s book luncheons I’d never faced such dilemmas. I pushed the plate away and prayed the next course would be vermin-free.

Because I’d been publishing for 16 years, I had contacts that crossed over into adult genres. I pitched my vague idea for a series (a woman consignment shop owner) to an editor. She suggested I create a series about a female meteorologist. Alrighty-then. I went to NOAA. I bought textbooks on meteorology. I watched Willard Scott. I attended a lot of mystery writing events, like Malice Domestic, where I bought crime scene tape, a Daffy Duck private eye tie for my husband, and a replica of the Maltese falcon.

At a publisher party, I chatted up my nonexistent book to the editor and even snagged the interest of a very good adult agent. It seemed I was welcome in this world. But I wasn’t, really. That inch worm was waving me away. People were nice but I never felt at home. Worse, I couldn’t confront the work. I read and talked and went to conferences, but I did not write.

Sleuthfest, the annual Mystery Writers of America conference, was held in Philadelphia that year. I cadged a ride with a fellow Sisters in Crime member. My husband warned me not to leave the hotel, Philly was dangerous. Two seconds after I threw my Laura Ashley bag in my hotel room, I was out on the mean streets. My clothes-sleuthing nose led me straight to an Express. I bought all new outfits for the conference.

I heard some of my favorite writers, like Michael Connelly. TV producer Steven J. Cannell, all Hollywood tanned and handsome, was the luncheon keynoter. Then everyone who had had a mystery novel published that year stood while the others applauded. And that’s when a little worm in my stomach turned over. My clothes weren’t wrong—I was.

I belonged with my own tribe. At the annual Children’s Book Guild awards luncheon, my name was called every single year and I always stood proudly with other writers who’d published books while people applauded. Kids’ books had been my passion since I was 15. It was time to get over my two-year snit.

Hollins University, Summer 2015 Children’s Lit Program

I’ve met a number of people who have confided frustration in trying to break into their chosen field. These days it’s both easier and harder to get a book accepted. Easier because so much help is available. When I began, there was Writer’s Digest when it was actually a digest, and The Writer. That was it. But it’s also harder now. Although thousands of books are published every year, there are fewer trade publishers. Of course, self-publishing, indie houses, and e-books are viable options.

In her book A Writer’s Guide to Persistence: How to Create a Lasting and Productive Writing Practice, Jordan Rosenfeld devotes an entire chapter to pushing too hard. “Go Where You Are Welcome” explores our need to seek approval, have our work validated. She examines the fear that someone else will grab our success before we can get there. This pressure is fueled by social media and marketing—build a platform, sell huge numbers of books, win awards. But no one can “steal” your spot. Your work is unique.

When we don’t get results, we persist in knocking at a door that may be locked to us. Rosenfeld doesn’t recommend that we give up, instead apply the “rule of welcome” and reevaluate our efforts. “Quit seeking approval,” she says. “Press pause on attempts to be as others think you should be or as you feel you should be in order to achieve.”

The welcome mat will be rolled out when “you are passionate about your ideas, you commit to doing the writing no matter what, you do your research, you seek avenues that align with your work, you make true connections with people.” But I do all that, you may say. Look again at those last two criteria—are you on the wrong path? Do you really feel a sense of rightness when you talk to an editor or an agent?

I felt no sense of rightness when I was trying to enter the adult mystery field because I wasn’t passionate or serious.

Rosenfeld suggests developing synchronicity in your writing practice. When the project you’re working on is right, things happen to reinforce its place in the universe. Small things, like walking into 7-Eleven and realizing you aren’t craving that Milky Way bar in your hand, but your character is. Stay open and pay attention, Rosenfeld advises, and synchronicity will find you.

She suggests keeping a synchronicity notebook in which you record all the little coincidences that enrich your project. “The more you track these events and situations, the stronger your lens will become to look for signs you’re moving in the right direction, and the more likely you will feel motivated rather than discouraged.”

And you won’t need a little green worm in your salad to send you down the right path.

June 19, 2015

Packing My Typewriter for Hollins

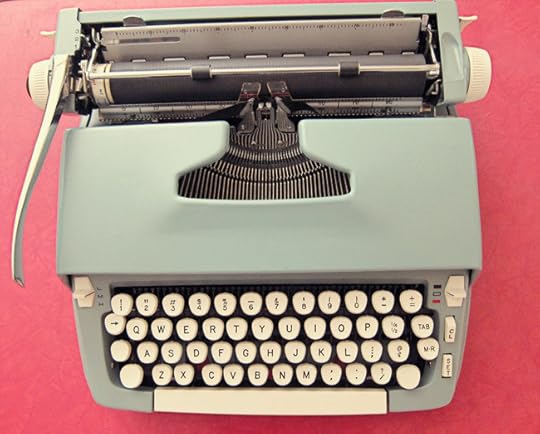

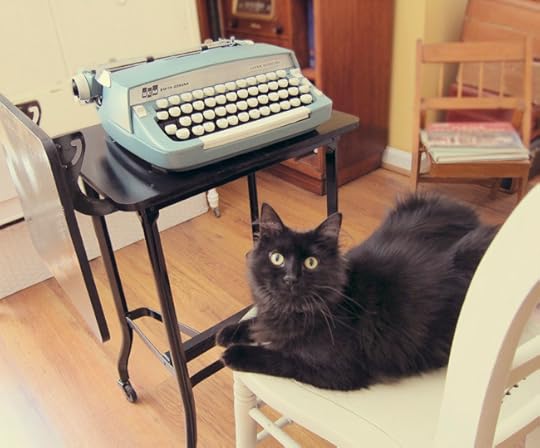

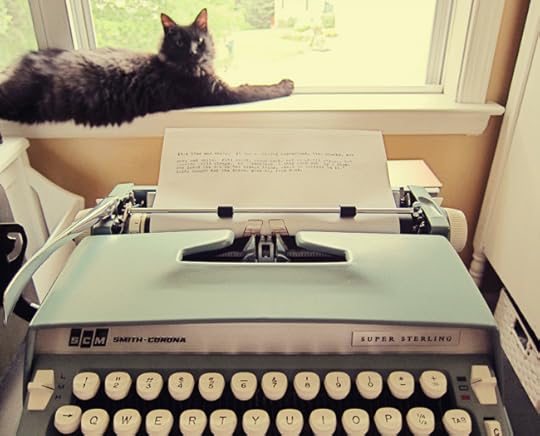

Yes, you read that right. I’m taking a typewriter to Hollins University. Not a display piece to hold photographs, but a working Smith-Corona Super Sterling in its original case. Its walking papers state it was purchased new in December, 1967. Now it’s mine.

Two things spurred me to buy another typewriter. One, a vague unease about composing on the computer, even after more than thirty years of “word processing.” The monitor shows nearly a full blank page, cursor urging me to start stringing words. It occurred to me that lately I’ve been trying to fill that page. A paragraph or partial page seems incomplete. I have to cover that white space.

And two, I bought a typewriter because of Barbara Kingsolver’s bobcat in the window.

Kingsolver is best known for her prize-winning books such as The Poisonwood Bible, Prodigal Summer, and Flight Behavior. She also writes crackerjack essays. “Knowing Our Place” (from Small Wonder) opens with, “I have places where all my stories begin.” She’s not referring to the places in her novels, but where she actually works.

Kingsolver lived part of the year between the mountains of southwestern Virginia and the rest in the “narrow riparian woodland stitched like a green ribbon through the pink and tan quilt of the Arizona desert.” [Book jackets forever declare that such-and-such author ‘divides his time’ between New York and Paris. If I ever get famous, I’m putting on my book jackets: She divides her time between Willow Springs and Scrabble, Virginia.]

Kingsolver’s cabin in Appalachia was built from chestnut logs. She hung out laundry, read out loud, weeded the vegetable garden. But mostly she wrote. “I work in a rocking chair on the porch, or at a small blue desk facing the window. I write a good deal by hand . . .”

In Arizona, she lived a house made of sun-dried mud, surrounded by mesquites and cottonwood that grew along an oasis of a creek in the Sonora desert. “I work at a computer on a broad oak desk by a different window, where the view is very different, but also remarkable.”

It has been my policy, ever since I became a full-time writer, that my work station face something dull—a closet door, a blank wall. Windows would prevent me from distilling scattered thoughts into pure, crystalline words (still waiting for that to happen).

One day in her Arizona house, Kingsolver sensed a presence over her shoulder. “I turned my head slowly to meet the gaze of an adolescent bobcat at my window.” She looked “straight into bronze-colored bobcat eyes” until he broke eye contact and walked away. “Some part of my brain drifted after him for the rest of the day . . . It’s a grand distraction, this window of mine.”

My window is behind me. Sometimes I glimpse wrens flitting by or wasps rappelling down the screen, but I have to turn my head to look. Sinking the hook, Kingsolver quotes Annie Dillard: “Beauty and grace are performed whether or not we will or sense them. The least we can do is try to be there.”

After I read that essay, I thought about Barbara Kingsolver writing on her porch in the mountains, or typing by the bobcat window. I’m not the type to take my laptop outside. Truthfully, I hate my laptop. The monitor is too small, the keyboard too flat. I use it at Hollins in the summers, at Bell House, and researching in libraries. That’s it. When I plugged it in after months, it required one hundred updates that took two hours to chew through. I felt like a bad laptop mother for neglecting it so long, but also annoyed.

I remembered the days before computers, when I rolled a piece of paper into my typewriter and just wrote. Somehow Kingsolver’s bobcat, her porch rocker, the one hundred updates, and the cold computer screen page coalesced into an image of myself sitting on my porch writing on a typewriter.

Not an electric typewriter, though I was tempted by an IBM Selectric (I got rid of two of those gorgeous machines when we moved here 20 years ago). I love the technology, but its cartridge ribbons are hard to come by.

After studying the best and most reliable machines, the Olympia SM9 came up. I looked across my desk, past my Dell internet computer and there, on a $9 typing table, sat an Olympia SM9 with a 13-inch carriage. A German workhorse I already owned. However, it’s a semi-portable, which means it’s heavy, and it needs a new ribbon.

I found a Smith-Corona Super Sterling in working order with a brand-new ribbon, in a shade hovering between turquoise and cornflower with cream-colored keys. I fell hard. $75. Two days later, Margie Irene arrived (I named it after my mother) with case, papers, and all. I loved it on sight.

I’m not throwing my computers out. But I am writing first drafts on the typewriter. There is no impatient cursor, no cold page to fill at once. And I’m not alone. Many writers are drafting old-school. British novelist Will Self switched because, “I felt oppressed by the distractions of digital media and longed for a certain level of clarity that the typewriter afforded. The Internet is of no relevance at all to the business of writing fiction directly [italics mine], which is about expressing certain kinds of verities that are only found through observation and introspection.”

Working on a typewriter is different. I’d forgotten the apostrophe is shift 8 and when the bell rings, you must return the carriage. But as Will Self noted, “…the computer user does his thinking on the screen, and the non-computer user is compelled, because he has to retype a whole text, to do a lot more thinking in the head.” Writing a misspelled, missing-letters first draft is not the end of the world. I’ll re-key it into the computer, effectively doing a simultaneous second draft.

For morning porch sessions, I bought a Korean War-era field typing table (no casters). The table and Smith-Corona are both coming to Hollins. I’ll set them up by the open window of my apartment. Soon sounds no one has heard in years—some have never heard—will float across Faculty Row. The ratchet of paper rolling into the platen, the clack of keys, the ding of the bell, the satisfied sigh of pages piling up.

When I come home, I’ll move my typewriter in front of the window and be present for acts of grace. Atticus will stand in for the bobcat.

June 8, 2015

Wonder-Words: Catch Them Before They’re Gone

Is there anything worse than being flattened by sickness in summer? An eighteen-wheeler virus Jake-braked through our house and left both me and my husband in the ditch. During conscious moments, feet snugged under a hubcap of a cat, I read the latest issue of Orion. The magazine subtitled Nature, Culture, Place invites the finest writers and I was delighted to see a piece by Robert MacFarlane.

MacFarlane, British nature writer and national treasure (like our Wendell Berry), mentioned he has been collecting words from old places used by crofters, farmers, colliers, shepherds, poets, walkers, and “unrecorded others for whom particularized ways of describing place have been vital to everyday practice and perception.” Wonder-words, MacFarlane calls them, like pirr, from the Shetland Islands, which means “a light breath of wind, such as will make a cat’s paw on water.”

He began collecting these near-forgotten words back in 2007, about the time he glimpsed the new edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary. Words were conspicuously missing—acorn, beech, bluebell, buttercup, cygnet, dandelion, fern, hazel, heather, heron, ivy, kingfisher, mistletoe, otter, pasture and willow, among others.

Nature words had been yanked like rotten teeth and replaced with shiny modern terms like attachment, block-graph, blog, broadband, celebrity, chatroom, committee, cut-and-paste, MP3 player, and voice-mail. You’ll find Blackberry instead of blackberry. The Oxford University Press admitted it had been under pressure to purge entries no longer relevant to techno-savvy children.

What will kids call those yellow flowers that sprinkle spring lawns like gold coins? And those large blue-gray birds that stalk frogs in shallow creeks? And what will they rake in the fall along with oak leaves . . . No, wait, they don’t rake any more, they’re indoors tweeting celebrities. They don’t even need a dictionary any more, there’s spell-check.

In fourth grade, I received my very own Thorndike-Barnhart Junior Dictionary. It cost $2.50 and I remember the exact moment Mrs. Stann placed my copy on my desk. The cover was red cloth with gold lettering. Black labeled indents made navigating the thick book easier. I opened it immediately, eager to meet all the words in the world, and carried my Thorndike-Barnhart with me every day. I read it like a novel.

Four years before, when we moved to our new house in the country, I was afraid of everything. I was afraid of our long gravel driveway to the highway. I was afraid of the trees, the woods that drew close like giants.

My stepfather let me tag after him as he did his chores. He answered my hesitant questions and taught me the names of things. Not just an oak tree but specifically black, red, white, pin, or chestnut. After a while I could identify pin oaks and chestnut oaks by their bark, leaves, and acorns. By learning their names, I realized that trees weren’t scary but had their place in the world. I became less afraid and began to take root in my new place, entwined with its spirit through language.

The new words in dictionaries are mostly retreads, truncated terms, or composites: “twitter,” “app,” and “Instagram.” We aren’t richer for them, especially if we’ve lost “acorn.” As MacFarlane’s article states, “If acorn goes from the lexicon, the game is up for nature in England.” I suspect the game is up for nature—and language—everywhere. Now we have smarter-sounding terms for nature, like environment and ecology.

In their sterile Common Core writing samples, students will likely define environment as “the surroundings in which a plant or animal operates.” Can we picture such a thing? We can picture an acorn. Emerson, one of America’s greatest nature writers, was a stickler about “fastening words to visible things,” just as my stepfather was a stickler about the exact species of oak.

As Robert MacFarlane traveled the far corners of the British Isles, he collected linguistic gems as ammil, a Devon word for the “thin film of ice that lacquers leaves, twigs and grass when a freeze follows a partial thaw, and that in sunlight can cause a whole landscape to glitter.” One exquisite word to describe a fleeting spectacle.

MacFarlane’s new book, Landmarks, about the reclamation of place-based language, will be published in the U.S. in September. I can’t wait to get a copy. I want to know more about Aunt Julia who was so rooted in her native Harris Island that she “came to think with and speak in its birds and climate.”

And I can’t wait to learn more wonder-words such as smeuse, “the gap in the base of the hedge made by the regular passage of a small animal.” As a kid I used to follow those little woods trails, trying to blend in with the brambles and bushes so the animals would think I belonged.

Now that I’m better (finally!), I’m taking a sharp look around, my feet planted firmly on the ground, careful to pin the right words on the wonders I see.

May 5, 2015

That Kansas Air

Sometimes we’re not ready to leave home, go on a business trip, or even go to the grocery store. We’re that involved with spring chores or our work. But sometimes we feel misaligned, out of plumb, ripping out rows of work to get back on track. Those times we’re eager to get away, breathe different air.

On Friday I left the air of Virginia—chilly and mizzling—to fly to Kansas, where I was giving a workshop for the Kansas SCBWI. I flew out of Richmond and took a connecting flight from Atlanta for Kansas City. Even with the awfulness of air travel (boarding is the worst), everyone wore the air of going someplace.

I made sure I had a window seat so I could see the Mississippi. The rumpled Appalachians and Ozarks smoothed out and there was the great river. Southeastern farms, laid out crazy-quilt style, gave way to neat, nine-patch Midwestern designs. You could pull those farms over your shoulders like eight-hundred thread count bedcovers.

From the airport I walked out with my hostess, Sue Gallion, into clean bright air. My allergies stayed on the other side of the Mississippi so I took a deep lungful. Sue, the advisor for the Kansas region, took me under her capable Midwestern wing. We became instant friends. As we drove south, I watched Kansas roll by. I heard birds I didn’t know.

This is a clean, neat, well-organized state with manicured municipal lawns and four-square buildings. Even the weeds, if there were any, behaved. It occurred to me that Sue, who planned my trip so quickly and efficiently I’m still flabbergasted, reflects the orderliness of her home state. Kansas people don’t mess around.

Kansas doesn’t mess around when it comes to barbeque, either. At Jack Stack, where I was taken to dinner, not only is it acceptable to eat like a registered hog, but expected. I did not disappoint.

Saturday I led a workshop on writing chapter books and middle grade fiction for nearly 60 people, but it seemed more like chatting with family. Everyone was Midwestern nice, but I learned too, from this lively, funny, and smart bunch. All too soon it was over.

Sunday I waited for my ride to the airport outside in crisp early air. Mourning doves were nesting on a beam next to the hotel entrance. The female mourning dove fluttered off the nest after incubating the eggs all night. The male took over for the day shift. Then Teresa, librarian/writer dynamo, picked me up. Doves cooed as I closed the car door.

At my gate, I watched a technician clean the cockpit windshield. It never occurred to me that jet windshields need cleaning, or that someone does it with a rag. The air around the bright blue plane shimmered.

Once onboard, I settled in my seat to read. I didn’t need to look out the window. Kansas had realigned my out-of-plumb self and cleared my vision.

In Richmond, I walked out into hot, humid air. While I was gone for three days, spring had slipped away and summer jumped up in its place. Trees flew new leaves like flags along the I-95 corridor and weeds cheered. I wasn’t in Kansas any more.

I slipped back into my home state and embraced the messy, verdant green, the cacophony of familiar birds multi-tasking. I eased back into my work, energized, and didn’t drop a stitch.

April 27, 2015

Why I Blog . . . and Take Pictures

Sunday arrives and I remind myself, lugging a basket of laundry as dust mice scuttle ahead of me, Must post to blog. On Sundays I often grocery shop, do laundry, vacuum, go out for lunch with my husband, and try to sort out the coming week. Thinking of a pithy blog post is often at the bottom of my list. Thinking of anything period is often at the bottom of my list.

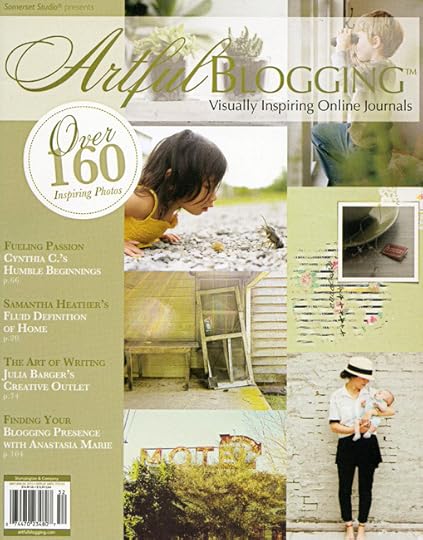

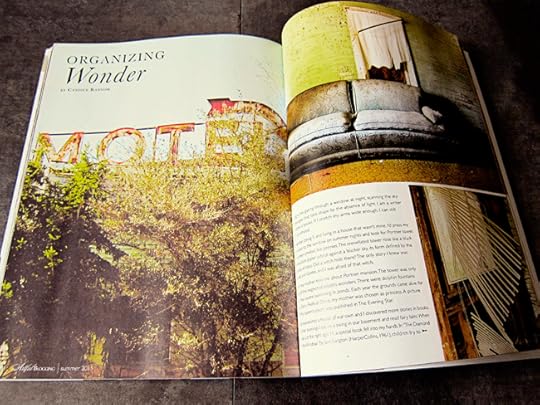

That’s why I sit myself down and do it. If I didn’t make myself think, yes, even on a weekend, even on Sunday, the day would be lost in dailyness. This week I thought I’d simply put up the above photo and announce that I’m a contributor to the new issue of Artful Blogging. Send up a flare, end of post.

Nope. Not letting myself off the hook that easily.

It’s true, my blog, a new essay, and my photos are featured in the Summer 2015 issue of Artful Blogging. If you don’t know this publication, it’s an feast of photographs and essays by bloggers who are artists, photographers, craftspeople, cooks, mothers, travelers, anyone who maintains a creative blog.

I’ve followed this magazine since its inaugural issue in 2008, before I began this blog. I drooled over the pictures, poured over the essays, spent time at the authors’ blogs. To say I’m gratified and flattered to be included is an understatement. My work is bookended by photographers who do not use point and shoot cameras set on auto!

By studying the magazine and other people’s blogs, I learned what makes an interesting photo and to include images that aren’t simply a visual “break” in my narrative. Several times I tried taking my photography to the next level. I bought books, enrolled in online and face-to-face classes, hung around with Donna Hopkins, a true photographer.

I ventured out into the world with my little Canon Powershot (and sometimes my Nikon), snapping pictures of old houses and cars and junkyards. National Geographic did not call. Good thing, because my camera is still on auto.

While my photos have gotten marginally better, the purpose of my blog has not changed. It’s the place where I think and work things out. I try to write shapely essays that anyone can relate to. The best part of blogging is that I can create a post, put it up, and be done. When you work on long-term projects, creating a blog post feels like a vacation.

My photography is stepping into my work-a-day writing. I take pictures for those long-term projects and not just for research. The camera has become another tool in my technique toolbox. From other people’s blogs (notably Donna’s), I’ve noticed photo collages. These artfully arranged objects can serve as a sketchbook of sorts.

Photo by Donna Hopkins of Patchwork Photos

Instead of just thinking about what my character likes or has, I arrange objects that represent my character and photograph them. As Donna told me, the very act of arranging—placing one object a half inch to the right and another a hair to the left—feels very zen. More importantly, arranging a composition gives me time to consider my character in a tangible sense.

Often when we create characters, we assign background information—color of hair, height, favorite flavor of ice cream, etc. Sometimes arbitrarily: my character loves blue and hates Brussels sprouts. Does she really? Or do we love the color blue and hate Brussels sprouts and transfer those likes and dislikes automatically?

By physically gathering things and then arranging them, the position of and space around the object holds weight. These are the items that matter to your character, in this particular way. I take the photograph of the collage and print it as part of my background notes. My character comes to life more organically.

I’ll continue to blog because I enjoy writing journal entries from my little corner of the world. And I’ll continue to take photos because it goes back into my work.

Magazine, paint chips, antique silver nut cup, duck egg shell.

Yet for the next three months, I’ll be able to walk into a Barnes and Noble anywhere and pick up Artful Blogging. I might even tell the person standing next to me that not only is my work included in the magazine, but two of my photos are featured on the cover.

For the next three months, I’ll feel like Dorothea Lange.

April 13, 2015

Street of Lost Steps

Life is a child at play, moving pieces in a game; the kingdom belongs to the child. Heraclitus

Saturday. A beautiful day to drive to a library event. My GPS guided me to a highway I hadn’t been on in over 25 years, Rt. 28 between Manassas and Centreville. Good thing I had GPS because I was lost on a road I’d traveled thousands of times growing up.

Abandoned children’s games in the little side street, the street of Lost Steps, with the chalk lines of hopscotch in the late afternoon sunlight and shadow. Charles Simic

Dozens of traffic signals caused cars to crawl, even early on a Saturday morning. I gawked at a world I didn’t know. Check-cashing shacks, used car lots, ethnic restaurants, payday loans places, tattoo parlors, gun shops, auto parts stores, psychics, every inch plastered with tawdry sprawl.

Not that Rt. 28 had ever resembled Rodeo Drive, but blaring development made me grip the steering wheel as though I were hurtling through purgatory. Only Kline’s Tasty Freeze, an old-fashioned walk-up dairy bar in the same location 70 years, served as my personal global positioning system, my landmark anchor.

In antiquity the game of hopscotch symbolized the labyrinth in which one kicked a small flat white stone—one’s soul—toward the exit, the vanishing point with its cloudless sky. Charles Simic

As a kid, I traveled this stretch of road in all weather, every season, all times of day and night, in the backseat, the front seat, and, as a teenager, a few times in the driver’s seat. Yet in my mind, I’m nine years old in the backseat of our fin-tailed gray Chevy Biscayne. We wing toward Centreville on Lee Highway—the first view of the whale-shaped Blue Ridge Mountains—and turn left onto Rt. 28, heading to town.

It’s Friday evening in early summer, payday, and the road is the same purplish-blue as the mountains it runs parallel to. Small white houses are dwarfed by “snowball” and forsythia bushes. Forsythias, past their bloom, spray green fountains, but hydrangeas burst with rockets of blue and lavender. Telephone poles advance and retreat, unfurling scalloped wires like holiday bunting.

Alone in the backseat, I am queen. I own that throne of checked buttoned plush, rule both windows, possess the houses and mailboxes my coach passes like royal subjects. The road is familiar and comforting in its sameness, yet any second something new could swim into my vision. On the way to Manassas, I am watchful with anticipation. We bump over the Bull Run bridge into the next county. The river flows slow and brown between red clay banks. My stepfather mentions a good fishing hole he used as a boy.

On the way home, I’m drowsy with content, clutching a new Little Lulu comic book, chewing one chocolate-covered caramel Pom-Pom after another from the five-cent box. My mother and stepfather murmur in the front seat. Rt. 28 is darker. Telephone poles blur by, the hydrangea blossoms are bowed with dew. The distant mountains slumber.

Saturday when I crossed the county line, I never even glimpsed the Bull Run River. I didn’t see the mountains, only high-rises and vast shopping centers. A labyrinth of overpasses confused the turn onto Lee Highway.

The German variation of hopscotch is called Himmel und Holle (Heaven and Hell). The player throws the stone in the first square (Earth), then hops to each square after kicking the stone ahead, avoiding the square of Hell, trying to reach the last square, Heaven.

Stopped at one of the ill-timed red lights, I sat, a solitary soul, in my truck. So did the person in the car next to me. And the person in the car in front. We were all sitting on the same road at the same time. It occurred to me that no one else noticed the changes along that road, no one else was upset by them. It didn’t matter what was there before, only what was there now. Moreover, we were all active in creating those changes, simply by idling a few minutes in that spot.

Heraclitus said we can’t step into the same river twice. Every time I journeyed down Rt. 28 and back again, my presence altered the landscape. And the landscape altered me. The road was not the same, and neither was I. But what nine-year-old wants to think about change unless she initiates it?

Solitude, my mother/tell me my life again. O.V. de L. Milosz

Let me sweep aside the clutter of development. Let me be nine and queen of the backseat on my purplish-blue road. Let me tell my life again, the way I want to.

April 6, 2015

Mad Men, Monet, Mammoths, and Me: Finally Finding My New York

New York–so much to see, so exhausting, so wonderful.

When I was 18, the man I was falling for took me to New York. We went one whirlwind day, driving five hours up and back in his new 1970 midnight blue Mercury Marquis convertible. Because I was going to be a writer, I was certain I belonged in New York. (I was also certain I belonged with this man, a huge mistake.)

I insisted we eat in the Writers and Artists restaurant at the gauche hour of 11:00 a.m. and was disappointed not to see one single writer or artist. Then: I was propositioned in Central Park and didn’t realize it, bought an over-priced original watercolor from a sidewalk artist, saw my first mime, and cried when a cafeteria server barked at me for not making up my mind fast enough. We drove out of the city with the top down. I gazed up at the star-lit skyscrapers, vowing I’d come back as a writer.

I did. More than ten years later, and with a different man, one who believed in me. I delivered a manuscript—my second published book—to my editor at Scholastic. My husband and I took the train, getting up at 3:00 a.m. to drive to the station. I wore jeans and a red “sheep” sweater (made popular by Princess Diana—rows of white sheep with one black sheep facing the other direction). A red Alice-in-Wonderland style ribbon held back my long hair. I was over 30 but looked 16. Still not ready for New York.

Ann Reit, my wonderful chic editor, took me to a restaurant where I had my first chocolate raspberry truffle. For the next few years, I hand-delivered my books, and came home with contracts. Ann showed me her city—her upper West Side neighborhood, Shakespeare & Co., the New School. New York meant the Metroliner (with dining service), lunch or dinner and show with my editor, the train back home.

Later I went to New York for conferences and conventions. The city meant Amtrak, Penn Station, hotels, Javits Convention Center, cocktail parties and receptions. I never went to a museum, never saw the Statue of Liberty, never did anything fun. I began to dread going to New York. So much so that years and years would go by between trips.

Two years ago, on a quick trip to attend the Children’s Choice gala, I visited the Strand bookstore and memorably walked the 30-some blocks to Penn Station with my luggage and bags of books. A year later I left a conference to see the “ABC of It” exhibit at the New York Public Library. There was another New York. In fact, there was a New York just for me. I only had to find it.

It began with a disappointing trip to D.C. this past November, when a friend and I visited the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. Instead of feeling close to natural history, I felt distanced from it. Inside the charming Beaux Arts building the exhibits felt modern and skimpy. And inside of me, a book that featured natural history was trying to be born.

I would go to New York. I’d visit the Museum of Natural History and anything else the book required. I went this past week, alone, for four days, a trip not associated with a conference or a convention. I went for work. I went for myself. I was ready.

Days from Mad Men’s finale, the end of my favorite show.

I got off the train, checked into my hotel, and hit the streets. I walked from 44th and 8th Avenue to 12th and Broadway, to the Strand bookstore. Along the way, I stopped at Books of Wonder. Real bookstores were my New York. I even visited the three-story Barnes and Nobles. It was freezing and raining, but bookstores kept me warm. I couldn’t walk five million blocks back—I’d rather lay down in the middle of Broadway and let taxis flatten me. So I learned the subway.

The next day I had an appointment at Random House—shades of visiting Scholastic. My editor took me to lunch at the Art and Design Museum. The elevator opened to a display of Pucci mannequins, naked and white, with people staring at them. I wished I’d captured that bizarre scene with my camera. At lunch I enjoyed a view of glass skyscrapers marching toward midtown. We shopped in the gift shop. I spent the rest of the afternoon on subways, thrillingly lost.

The oasis of Central Park.

I don’t know why I thought I’d be alone at the Natural History Museum. Entire countries of tourists were bused in every day. Spring-break kids descended in swarms. Rather than wait with the crowd, I wandered around Central Park until the museum opened. Crocuses were pushing through leaf litter. I climbed rocks and dodged joggers on winding paths. This was my New York.

Inside the museum, a door opened inside me. It led straight to my ten-year-old self, the kid who loved all things nature. I wandered through galleries of dioramas (absent in the Smithsonian) I wanted to step in, past sweeping murals, dinosaur skeletons, gems, birds, amazement at every turn. I stayed until closing and missed half the exhibits. I went to be amazed and to learn. I went to find something I didn’t know I needed until I saw it.

The next day I had to go home, but I hoofed it to the Modern Museum of Art. I had one hour. I went looking for the shadow boxes of Joseph Cornell. After I found those, I had thirty minutes. I passed up Rothko and Warhol for Monet’s staggeringly beautiful water lilies—entire walls of spring. People sat on the bench in front of one of the world’s greatest masterpieces, gazing at their phones. This was New York, too.

On the train home, winter landscape spooled outside my window—leafless trees, platinum-tinged rivers. Gradually the scenery greened until we reached Virginia where redbud and cherry blossoms, forsythia and daffodils welcomed me home again. I got off the train, tired but happy, with an extra suitcase, feet four sizes bigger, an empty wallet, and a head filled with astonishing images.

I had found my New York. I can’t wait to go back. And when I go, it won’t be in a 1970 midnight-blue Mercury Marquis, but coach-class Amtrak. I’ll be with the man who gave me the real New York and much more. And I’ll give him the Natural History Museum.

I had found my New York. I can’t wait to go back. And when I go, it won’t be in a 1970 midnight-blue Mercury Marquis, but coach-class Amtrak. I’ll be with the man who gave me the real New York and much more. And I’ll give him the Natural History Museum.