Packing My Typewriter for Hollins

Yes, you read that right. I’m taking a typewriter to Hollins University. Not a display piece to hold photographs, but a working Smith-Corona Super Sterling in its original case. Its walking papers state it was purchased new in December, 1967. Now it’s mine.

Two things spurred me to buy another typewriter. One, a vague unease about composing on the computer, even after more than thirty years of “word processing.” The monitor shows nearly a full blank page, cursor urging me to start stringing words. It occurred to me that lately I’ve been trying to fill that page. A paragraph or partial page seems incomplete. I have to cover that white space.

And two, I bought a typewriter because of Barbara Kingsolver’s bobcat in the window.

Kingsolver is best known for her prize-winning books such as The Poisonwood Bible, Prodigal Summer, and Flight Behavior. She also writes crackerjack essays. “Knowing Our Place” (from Small Wonder) opens with, “I have places where all my stories begin.” She’s not referring to the places in her novels, but where she actually works.

Kingsolver lived part of the year between the mountains of southwestern Virginia and the rest in the “narrow riparian woodland stitched like a green ribbon through the pink and tan quilt of the Arizona desert.” [Book jackets forever declare that such-and-such author ‘divides his time’ between New York and Paris. If I ever get famous, I’m putting on my book jackets: She divides her time between Willow Springs and Scrabble, Virginia.]

Kingsolver’s cabin in Appalachia was built from chestnut logs. She hung out laundry, read out loud, weeded the vegetable garden. But mostly she wrote. “I work in a rocking chair on the porch, or at a small blue desk facing the window. I write a good deal by hand . . .”

In Arizona, she lived a house made of sun-dried mud, surrounded by mesquites and cottonwood that grew along an oasis of a creek in the Sonora desert. “I work at a computer on a broad oak desk by a different window, where the view is very different, but also remarkable.”

It has been my policy, ever since I became a full-time writer, that my work station face something dull—a closet door, a blank wall. Windows would prevent me from distilling scattered thoughts into pure, crystalline words (still waiting for that to happen).

One day in her Arizona house, Kingsolver sensed a presence over her shoulder. “I turned my head slowly to meet the gaze of an adolescent bobcat at my window.” She looked “straight into bronze-colored bobcat eyes” until he broke eye contact and walked away. “Some part of my brain drifted after him for the rest of the day . . . It’s a grand distraction, this window of mine.”

My window is behind me. Sometimes I glimpse wrens flitting by or wasps rappelling down the screen, but I have to turn my head to look. Sinking the hook, Kingsolver quotes Annie Dillard: “Beauty and grace are performed whether or not we will or sense them. The least we can do is try to be there.”

After I read that essay, I thought about Barbara Kingsolver writing on her porch in the mountains, or typing by the bobcat window. I’m not the type to take my laptop outside. Truthfully, I hate my laptop. The monitor is too small, the keyboard too flat. I use it at Hollins in the summers, at Bell House, and researching in libraries. That’s it. When I plugged it in after months, it required one hundred updates that took two hours to chew through. I felt like a bad laptop mother for neglecting it so long, but also annoyed.

I remembered the days before computers, when I rolled a piece of paper into my typewriter and just wrote. Somehow Kingsolver’s bobcat, her porch rocker, the one hundred updates, and the cold computer screen page coalesced into an image of myself sitting on my porch writing on a typewriter.

Not an electric typewriter, though I was tempted by an IBM Selectric (I got rid of two of those gorgeous machines when we moved here 20 years ago). I love the technology, but its cartridge ribbons are hard to come by.

After studying the best and most reliable machines, the Olympia SM9 came up. I looked across my desk, past my Dell internet computer and there, on a $9 typing table, sat an Olympia SM9 with a 13-inch carriage. A German workhorse I already owned. However, it’s a semi-portable, which means it’s heavy, and it needs a new ribbon.

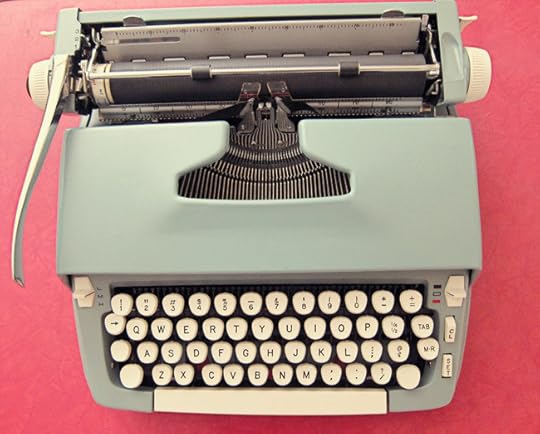

I found a Smith-Corona Super Sterling in working order with a brand-new ribbon, in a shade hovering between turquoise and cornflower with cream-colored keys. I fell hard. $75. Two days later, Margie Irene arrived (I named it after my mother) with case, papers, and all. I loved it on sight.

I’m not throwing my computers out. But I am writing first drafts on the typewriter. There is no impatient cursor, no cold page to fill at once. And I’m not alone. Many writers are drafting old-school. British novelist Will Self switched because, “I felt oppressed by the distractions of digital media and longed for a certain level of clarity that the typewriter afforded. The Internet is of no relevance at all to the business of writing fiction directly [italics mine], which is about expressing certain kinds of verities that are only found through observation and introspection.”

Working on a typewriter is different. I’d forgotten the apostrophe is shift 8 and when the bell rings, you must return the carriage. But as Will Self noted, “…the computer user does his thinking on the screen, and the non-computer user is compelled, because he has to retype a whole text, to do a lot more thinking in the head.” Writing a misspelled, missing-letters first draft is not the end of the world. I’ll re-key it into the computer, effectively doing a simultaneous second draft.

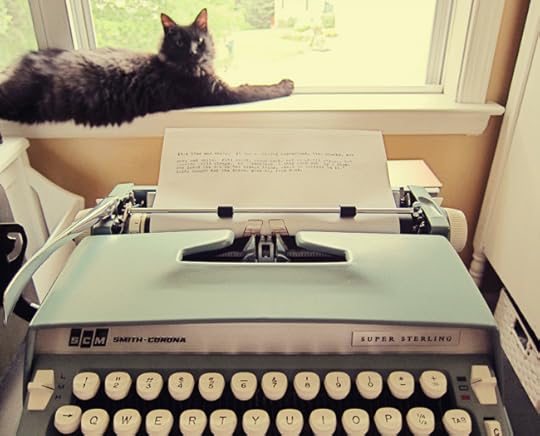

For morning porch sessions, I bought a Korean War-era field typing table (no casters). The table and Smith-Corona are both coming to Hollins. I’ll set them up by the open window of my apartment. Soon sounds no one has heard in years—some have never heard—will float across Faculty Row. The ratchet of paper rolling into the platen, the clack of keys, the ding of the bell, the satisfied sigh of pages piling up.

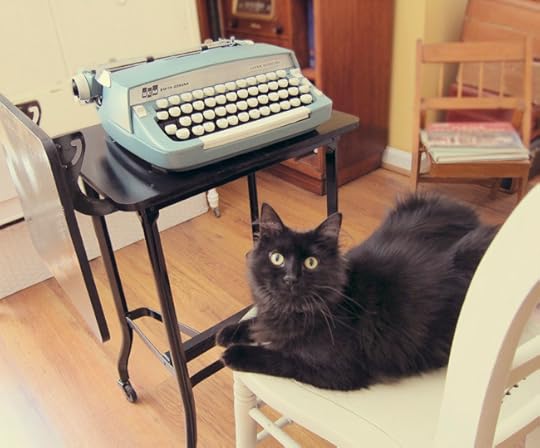

When I come home, I’ll move my typewriter in front of the window and be present for acts of grace. Atticus will stand in for the bobcat.