Missing: The Children of Summer

It was a place I often thought about. I located a lot of my imaginings in it. ~~ Wendell Berry

As I cruised through my neighborhood last Thursday afternoon, I felt like an extra in a Charlton Heston sci-fi movie, “Soylent Green,” perhaps, or maybe “The Omega Man.” When I left for Hollins University back in June, kids were always outside, playing soccer, drawing on sidewalks, tossing Frisbees, turning newly-learned cartwheels.

Now the streets were silent and empty. Bikes were flung in front yards as if their owners had been vaporized. Our cul-de-sac alone is home to seventeen kids of various ages, but not a single one was in sight. It wasn’t until Sunday evening, long after the sun had dipped over the treetops, but well before lightning bugs rose and sparked from the clover, that I saw my first child outside. She ran indoors as if ordered by martial law.

Yes, it’s another hot July in Virginia so everyone takes refuge in air-conditioned buildings. But it’s always hot in Virginia in July. The house I grew up in didn’t have a/c or even a fan, except for the window fan in the grownup’s bedroom and that was only switched on after dark. What did us kids do all day? We stayed outside. Being outdoors was preferable to being indoors because that’s where we became our summer selves.

For me and my town cousins, our summer selves swapped Classic comics under the big silver maple tree. We argued whether Kool-Aid or Cheer-Aid was better. We fed green grapes to the neighbor’s chickens. We ambled through the field behind the lumber yard, scouting killdeer nests. We slipped on moss-slicked mussels in Milford Mills Creek. We played Red Light, Green Light among fireflies. After our baths, fragrant with talcum powder, we lay across the bed to catch the faint breeze, watch the blinking radio tower and make ambitious plans for the next day.

At home, I claimed my own summer kingdom. In the woods, I rode a bouncy sapling over imaginary prairies. I built a fort out of a roll of chicken wire and a musty tarp. I read Nancy Drew, the yellow-back books, in my tree house. I played in the woods and fields alone and unsupervised. I was always (well, usually) within hollering distance. Once, I crossed a little red bridge arching over a creek that led to rustic Japanese-style buildings and an in-ground pool. I wandered around the strange camp, enchanted, then found my way home. I never located that camp again.

But it was okay. The camp, like the horse-tree, the chicken-wire fort, intrepid Nancy Drew, the back yard, the front yard, the sedge-y margin between garden and woods, all formed the place of my summers. And that place was mine by right. Woods and fields, any wild outdoor spaces, belong to children.

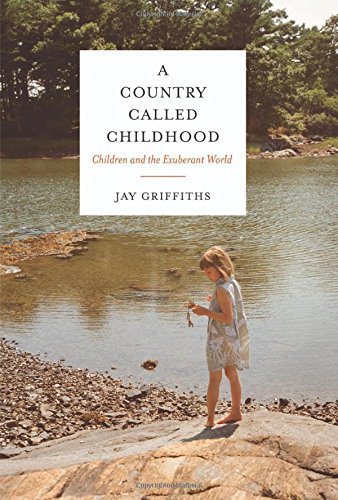

In her book A Country Called Childhood: Children and the Exuberant World, Jay Griffiths names nineteenth-century poet John Clare as the patron saint of childhood. “Clare writes of the land as if he were a belonging of the land, as if it owned him . . . his childhood belonged to that land and to its creatures; he knew them all and felt known in turn.” Making her case for nature-deficient children, Griffiths threads ribbons of Clare’s poetry about his childhood “lost in a wilderness of listening leaves,” “roaming about on rapture’s easy wing.”

Recently I stumbled on aerial photographs of the area where I grew up. With a click of the mouse, I peeled back layers and years, the same spot in 1979, in 1968, 1963, down to 1962, when I was ten. And there were my fields and woods, the strange camp, the holly tree in the front garden, even the hog pen. The location of a lifetime of imaginings. I touched the monitor glass, willing it to vanish so I could run barefoot in that grass again.

Over the decades I’ve watched as government, schools, and parents annexed the country of childhood. Driven by litigation and ever-increasing safety standards, communities and schools build playground equipment so tame—no angles, corners, or edges—that older kids become quickly bored. Recess has been chipped away or morphed into organized sports. The number of kids who walk to school—or walk anywhere—has dropped significantly since the 1970s.

When the kids in my neighborhood do play outside, they stay confined to their small front yards, or the cul-de-sac, almost always with a parent nearby. There is no chance for them to belong to a patch of asphalt, to be owned by a square of neatly-manicured lawn. Certainly no opportunity to slap together a fort from rusted chicken wire or discover a mysterious camp in the woods or feel known by birds and wild flowers.

Where are the children of summer today? They are holed up in their bedrooms in self-imposed curfew, watching TV or playing computer games or constructing Lego sets with detailed directions. Their freedom has been chiseled into a safe haven . . . or a cage.

Worse, they don’t even know what they are missing.

As a children’s writer, I’ve preferred to write realistic fiction about kids who sort themselves into pack hierarchies, explore, make up their own traditions and games, and rearrange the landscape to locate their imaginings, just as I did. These days I’m writing the same type of books, but they are fantasy.

At night when my mind idles, I think about the places that shaped my childhood and wonder what the children of summer today will remember when they are grown up.