Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 47

October 12, 2016

Views on Tobacco in 1832

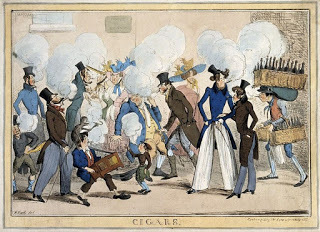

Cigars, by H. Heath (1827)

Loretta reports:

Cigars, by H. Heath (1827)

Loretta reports:From the time Sir Walter Raleigh brought it to England, tobacco had its detractors as well as proponents.

Henry James Meller's Nicotiana (1832), whose full title is almost as long as one of its chapters, is very much a pro-tobacco document. However, it’s also an interesting historical one. I chose one from hundreds of possible excerpts, mainly because this isn’t the only 1800s book I've found recommending tobacco as a preservative for teeth.

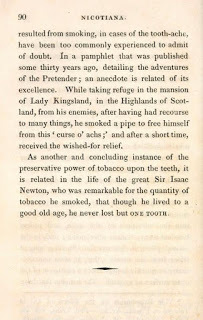

Tobacco for teeth

Tobacco for teeth

More tobacco treatment

More tobacco treatment

If you start on page 83 ,

you can learn about the many ailments it was alleged to cure, including lung ailments.

Cigars, by H Heath 1827 , courtesy Wellcome Images via Wikipedia.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on October 12, 2016 21:30

October 10, 2016

Sewing in a London Garden, c1800

Isabella reporting,

Since my last two posts have featured an 18thc sampler and another worked in 1673, it's not surprising that embroidery and sewing have been in my thoughts lately. When I came across this charming painting with women sewing in a London garden, I knew I had to share it here. As always, please click on the images to enlarge them.

The Chalon Family in London was painted around 1800 by Jacques-Laurent Agasse (1767-1849), who was known primarily as a painter of animals. Born in Switzerland, he studied art in Paris, and came to England in the late 18thc to paint the portraits of the favorite dogs and horses (though he also painted at least one giraffe) of the British aristocracy. Unfortunately, Agasse seems to have suffered the fate of many artists who have more creative talent than business acumen, and, as one historian put it, he "was born poor and died poor."

So who are the people in this painting? I'm guessing that this is the Chalon family mentioned in an 1862 edition of the Art Journal. These Chalons were French Protestants, driven by the French Revolution first to Switzerland, and then finally settling in London. The two sons of the family, Alfred and John Chalon, both in time became artists, and it seems likely they would be acquainted with Agasse, a fellow emigre from Switzerland who was also familiar with Paris.

It's an informal painting, the kind of picture that artists make as gifts for friends or for their own amusement, and small (only about 5" x 7".) Even though the specific identities of the people have been forgotten, they definitely have the look of a family at ease with one another. The women are engaged with their work, while the men talk over the wall. Though there's no documentation, I wouldn't be surprised if the man leaning over the fence was Agasse himself, bottom left.

But all that speculation aside, there's a wealth of details in the clothing of the four women. The oldest woman, upper left, sitting by herself and warily looking up at the artist, is dressed in the style of an earlier generation, in a plain gown, kerchief and ruffled cap. She's also wearing a floral-printed pinner apron, something I can't recall seeing before (Has anyone else out there seen one in a collection or in another painting?) Instead of needlework, it appears that she's peeling white turnips with a plate of peeled ones on the ground beside her, and more turnips with the leaves still attached to her left.

The four younger women are much more stylishly dressed in the high-waisted gowns and bonnets of the early 19thc. I'm particularly intrigued by the blue over-bodice or sleeveless spencer with the little ruffle at the back - don't you wish she'd turn around to show the front?

Gathered around a polished table and seated in chairs that were probably brought outdoors from an inside parlor, the women are making the most of the sunlight, workbaskets at the ready. The woman in the center is wearing eyeglasses, and I wonder if the woman to the left is also wearing them. Eyeglasses of the era didn't necessarily hook around the ears, but instead were secured with a ribbon through the bows and across the back of the head; is the black ribbon just above her nape attached to her eyeglasses?

The Chalon Family in London by Jacques-Laurent Agasse, c1800, Yale Center for British Art.

The Chalon Family in London by Jacques-Laurent Agasse, c1800, Yale Center for British Art.

Published on October 10, 2016 21:00

October 9, 2016

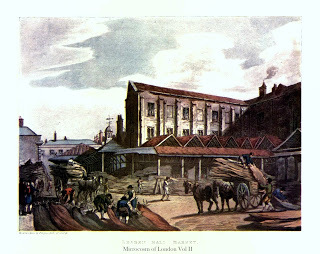

Leadenhall Market in 1815

Leadenhall Market

Loretta reports:

Leadenhall Market

Loretta reports:I’ve previously posted excerpts ( here and here ) from the Alimentary Calendar section of Ralph Rylance’s The Epicure’s Almanack , originally published in 1815 and republished in with 2012 extensive, useful notes.

The following excerpt is from the section on markets in and about London. There were quite a few (more than I was aware of). Mr. Ryland rates Leadenhall Market as Number One.

“Leadenhall Market, independently of the sales of hides and leather effected there, is by far the most considerable market in London. The articles sold here are town and country-killed meats of every sort, and of the primest quality. In addition to the usual variety of fine beef, veal, and mutton, some of the first rate butchers here expose, during the winter season, specimens of very delicate house-lamb, which is usually sold by the quarter, at Christmas tide from fifteen to twenty-five shillings each.”

Meat Market by Pollard

The meats include all possible cuts of pork, as well as poultry:

Meat Market by Pollard

The meats include all possible cuts of pork, as well as poultry:“Not only turkies, bustards, geese, peacocks and peahens, guinea fowls, pullets, capons, pigeons, ducks, wild and tame, widgeons, teal, plovers, quails, woodcocks, snipes, larks, and all other lawful game are sold here.”

Unlawful game was sold as well, under the counter, by a method of coded words.

“Around the wholesale poultry-market are the shops of several retail poulterers of great fame, such as Messrs. Mott’s. Here are roasting-pigs, eggs, and fresh-butter, in great abundance; nor is there wanting a proportionate supply of the finest fish in season.” Here also are two or three excellent tripe-shops. This is the most considerable market in London for tame and wild-rabbits, wild in particular, which arrive every day during the season from the several warrens in Essex, Herts, and Suffolk.”

Starting here you will you'll find a detailed history and description of Leadenhall Market, including which days which items were sold.

Image above, from Ackermann's Repository, courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art via Internet Archive. Image below, James Pollard, The Meat Market , courtesy Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on October 09, 2016 21:30

October 8, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of October 3, 2016

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• The weathervanes of old London.

• A crewel pocketbook for Benjamin Stuart, 1763.

• Beautiful images of New York and New England by Robert L. Bracklow, a weekend photographer in the 1890s.

• Unusual suspects: finding the humanity in vintage mugshots .

• Giles Cory, the only person in American history pressed to death by a court of law.

• The links between Queen Elizabeth I and the Muslim rulers of the late 16thc: England's forgotten Muslim history.

• Image: Beautiful woodcut-printed kite, c1855.

• Time-travel down NYC's Fifth Avenue with photographs from 1911 and today.

• Death personified: the many different appearances of death in culture.

• Runaway ! Recapturing working women's dress through runaway advertisement analysis, 1750-90.

• "Every minutes counts": the legacy of photojournalist Katherine Joseph .

• Drowning in Tudor England: Why was water so dangerous?

• Forgotten Georgette Heyer stories to be republished.

• Image: A page filled with drawings and signatures, c1909, from the visiting book kept by Lady Olwen Ponsonby, daughter of the eighth Earl of Bessborough.

• Snakes, mandrakes, and centaurs: a medieval herbal now online.

• The opposite of a muse : for two decades a medical secretary in Paris persuaded scores of renowned photographers to take her picture (NSFW).

• New postage stamps honoring Agatha Christie don't just celebrate her mysteries - they contain their own.

• Image: A flashy 1920s billboard advertising "Holeproof Hosiery ."

• The monstrous 18thc Beast of Gevaudan .

• How an imaginary island - said to be inhabited by sorcerers and giant black rabbits - stayed on maps for five centuries.

• What to expect when you're expecting, from a 1671 midwife .

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on October 08, 2016 14:00

October 6, 2016

Friday Video: Cooking 101 for the 20th century

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Someone recently told me that the height of gourmet dining early in his adult life was Trout Almondine, and that reminded me of going to fancy restaurants decades ago, where it did indeed star on the menu.

Most of what’s in the film is strange to me, but then, I did grow up in an immigrant household, in New England, and wasn’t exposed to much of the food that my husband, for instance, grew up with in the South. Of course, watching some of our cooking shows today, the people in the film likely would have been equally puzzled.

I wonder how many of these food ideas traveled from Britain to the U.S. or vice versa. I also wonder how many of us dress to cook in the style of the woman in the first segment. But I do lust for her jewelry. And her dress. And the mid-century dishware.

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post.

Published on October 06, 2016 21:30

October 5, 2016

An Early Sampler from Salem, MA, 1673

Isabella reporting,

Isabella reporting,Here's another sampler from the exhibition Embroidery: The Language of Art, currently on display at Winterthur Museum . This one, too, doesn't fallow into traditional notions of what a sampler should be.

Most Americans today think of 17thc New England as a mythical Pilgrim-Land , where everyone is dressed in black with buckles on their hats, barely scraping out an existence in the new land before they finally erupt into the paranoia and persecution of the witch trials. It's seen as a grim, forbidding place where it's always winter, and it's more than a little scary.

Yes, the first years of the Massachusetts Bay Company were grim. But by the middle of the century, life was growing more comfortable. Many of the settlers in the Boston area were prospering, and actively trading by ship with London, and therefore with the rest of the world. The silk thread for this sampler likely came in one of those ships, and it could have come to a Boston or Salem shop from silk manufacturers in France, Italy, or even China. Even those north American colonies were already part of a global economy.

This sampler was made fifty years after the first Pilgrims landed at Plymouth, and twenty years before the infamous witch trials. Sarah Collins, the young woman who made the sampler, signed and dated her work in the bottom rows of letters. She lived in Salem, a coastal town about twenty miles outside of Boston with a good harbor, and she must have belonged to one of the families that was benefiting from this shipping trade. Clearly she wasn't required to work all day in the fields or preparing food for her family's sustenance, as girls might have done earlier in the colony's history. Instead she had sufficient time to devote to learning elegant, decorative needlework like this, and she was likely encouraged to do so as a sign not only her own skill, but as proof of her family's gentility.

The stitches and patterns are traditional designs that, once learned, could be employed in different ways. Letters and numbers would have been used to mark linens, shifts, and shirts, while the floral designs could embellish both clothing and household linens. Most of the sampler is worked in cross stitch, although there are some more linear stitches used as well. (Compare these geometrically-inspired designs with the more free-flowing flowers of the needle lace sampler I posted earlier from the 1790s.) Though faded with time, the colors would once have been rich and vibrant, and their selection would have been an integral part of Sarah's creation.

What impressed me the most, however, is not only Sarah's skill at needlework and design, but also the extraordinary tidiness of her work. The sampler is displayed sandwiched between two sheets of Plexiglas so that both sides are visible. If it weren't for the letters being backwards and the colors of the thread being brighter on the reverse (shown above right), it would be impossible to tell the right from the wrong side of the sampler. For Sarah, Puritan Massachusetts wasn't necessarily gloomy, but a place that included flowers, colors, and gleaming silk on fine linen - and beautiful embroidery.

Winterthur will be hosting a needlework conference in connection with this exhibition on October 14-15, 2016. Entitled Embroidery: The Language of Art, the conference speakers will include international experts on needlework as well as hands-on workshops in the needle arts. Click here for the conference brochure for more information.

Sampler, worked by Sarah Collins, 1673. Winterthur Museum. Photographs copyright Winterthur Museum.

Published on October 05, 2016 21:00

October 3, 2016

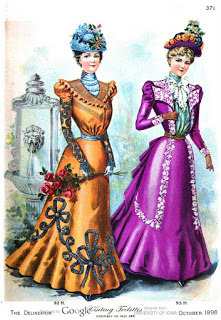

Fashions for October 1898

1898 suits

Loretta reports:

1898 suits

Loretta reports:It appears that 1898 continued a change in fashion begun in 1897, when the huge leg o’ mutton sleeves disappeared, along with clashing colors. C. C. Willett Cunnington, in English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century tells us:

“The new conception was that the dress should be fluffy and frilly, undulating in movement with ripples of soft foam appearing at the feet; colours harmonizing with each other, surfaces broken with flimsy trimmings and revealing submerged depths of tone. The softened outlines, willowy and slender, created the illusion that these aery habitations must be occupied by beings composed of stuff less solid than flesh and blood. ... This style survived well into the present [20th] century and during the last years of the nineteenth century did not arrive at its maturity.”

1898 visiting dresses

1898 visiting dresses

According to the book, “The emancipatory movement associated with the nickname ‘ the New Woman’ ” along with the personal freedom the bicycle offered women , explains the change. “The alarm created by such innovations created, as it usually does, an apparent swing-back to the ultra-feminine in fashion. By such devices the pace of progress is seemingly checked and the male sex reassured. After a stride forward woman will affect to mark time by a return to fluffiness.”

1898 fashion description

1898 fashion description

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on October 03, 2016 21:30

October 2, 2016

A Beautiful Needle Lace Sampler, 1795

Isabella reporting,

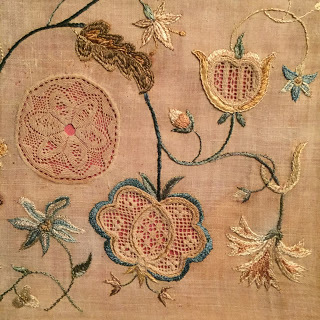

Isabella reporting,Last week I visited one of my favorite places, Winterthur Museum, and among the current exhibitions is Embroidery: The Language of Art . Our readers know that embroidery is one of my absolute favorite things, and this exhibition had plenty of examples to make me ooh and ahh.

For most modern people, the word "sampler" means cross-stitched letters and designs. It can be that, yes, but a sampler can also feature all kinds of needlework, from decorative stitching to darning stitches and even the so-called plain stitches used to construct clothing and household goods. Most samplers were worked by schoolgirls as they learned the various stitches. Not only were the samplers an educational tool, but they could become a kind of record of stitches for future projects. If a sampler was decorative as well, then it could also be proudly displayed by the girl's family as proof of her newly-acquired expertise.

The identity of this sampler's maker is now sadly lost beyond her initials, but her exquisite workmanship remains. Worked in a school in the Philadelphia area, the sampler features both traditional embroidery stitches and needle lace to create a stylized basket of flowers, a motif popular with embroiderers in many different cultures. The sampler is worked in silk thread on linen. (As always, please click on the images to enlarge them.)

Needle lace, sometimes called Dresden work, involves cutting or drawing away parts of the supporting fabric and then using the needle to weave elaborate patterns to fill in the empty spaces. This example must have required phenomenal skill and patience from its young maker. The needle lace sections are done with very tiny stitches - the geometric circles shown in the details are only about 1-1/2" in diameter. (The pink backing is modern to provide contrast.)

Yet there's an unmistakable exuberance and joy to the design as well. Too often fine embroidery seems like drudgery to 21st century eyes, but a piece like this is clearly as much an expression of the young needleworker's imagination as a painting might have been. You can see her enjoyment in her design and her pride in the precision of her stitches. How fortunate her work has survived so we can enjoy it, too!

Above: Sampler, by "M.S.", worked in the Delaware Valley, 1795. Winterthur Museum.

Published on October 02, 2016 17:00

October 1, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of September 26, 2016

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• The amazing 19thc butter sculptures of Caroline S. Brooks.

• A humble skirt worn by an enslaved child finds a place in history.

• The mystery of the phantom page-turner .

• Native American captive Elizabeth Hanson, a Quaker mother in 1724 New England.

• Explore all the treasures of the Red Drawing Room at Blenheim Palace in 360 degrees.

• Skeleton of a teenaged girl confirms cannibalism at Jamestown.

• Image: Gold leaf on Coptic shoes , making a fashion statement while strutting the streets of ancient Egypt.

• Fingerspitzenformer , otherwise known as a late 19thc fingertip shaper. Really.

• Danger and the amorous woman: prostitution in 19thc Britain.

• An inspired pot.

• Many questions from the title alone of this 1892 advice book to read online: " How to Get Married Although a Woman, or, The Art of Pleasing Men" by a Young Widow.

• Image: Enchanting c1915 autochrome portrait of a lady happily surrounded by her books.

• Inside the old-fashioned world of New York's vintage girls .

• Benjamin Franklin's silver court sword is coming up for auction.

• Why John Hancock's signature was so big and other hands FAQs about the Declaration of Independence .

• Image: Bonnie Prince Charlie's stunning silver-hilted broadsword , found on the battlefield after the defeat at Culloden.

• Domestic and imported woolen cloth in a medieval town.

• The Wolf's Water , coming from a historic London pump.

• Queen's House , Tower of London: the most complete high-status, timber-framed building in London that predates the Great Fire of 1666.

• The Countess Greffulhe, Proust's fashion queen, reigns again in a new exhibition.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on October 01, 2016 14:00

September 29, 2016

Friday Video: Why Share a Picture of a Meal When You Can Eat It? (18thc Style)

Isabella reporting,

Yes, I have an Instagram account , but no, I don't post pictures of food before I eat it (okay, so there was this one pumpkin pie I made for Thanksgiving - pie pride! - but I swear, that's IT.) Having to wait with food on the table while someone else hovers with their phone, trying to compose the perfect shot of their rapidly-cooling meal to post on IG, Yelp, or a personal foodie blog....no. Just no.

All of which is why I found this advertisement so entertaining. It features that too-familiar, first-world-scenario, but from an 18thc perspective.

Relax, indeed.

Published on September 29, 2016 21:00