Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 50

August 17, 2016

E.B. White on White & Brown Eggs

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:I’m writing this while up in Blue Hill, Maine, in a local library, where works of E.B. White , who lived not far from where I'm hanging out on a cloudy day, stand on shelves in a lovely room focused on the area and its many talented residents and long-time visitors.

The essay, written in 1971, touches on something we history nerds constantly encounter in our research: attempts by visitors to explain the natives. Just because the writer is highly regarded, well-read, and observant, doesn’t mean he/she has a clue.

In this excerpt from a slightly longer essay, "Riposte" (which I highly recommend), Mr. White takes up the Englishman J.B. Priestley’s comments in the New York Times about eggs in the U.S.

~~~

In America [Priestley] says, “brown eggs are despised, sold off cheaply, perhaps sometimes thrown away.” Well now. In New England, where I live and which is part of America, the brown egg, far from being despised, is king. The Boston market is a brown-egg market.

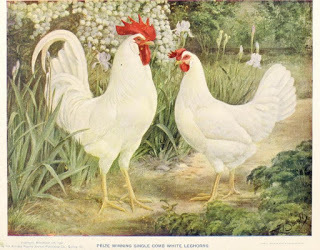

“The Americans, well outside the ghettos,” writes Mr. Priestley, “despise brown eggs just because they do seem closer to nature. White eggs are much better, especially if they are to be given to precious children, because their very whiteness suggests hygiene and purity.” My goodness. Granting that an Englishman is entitled to his reflective moments, and being myself well outside the ghettos, I suspect there is a more plausible explanation for the popularity of the white egg in America. I ascribe the whole business to a busy little female—the White Leghorn hen. She is nervous, she is flighty, she is the greatest egg machine on two legs, and it just happens that she lays a white egg. She’s never too distracted to do her job. A Leghorn hen, if she were on her way to a fire, would pause long enough to lay an egg. This endears her to the poultrymen of America, who are out to produce the greatest number of eggs fro the least money paid out for feed. Result: much of America, apart from New England, is flooded with white eggs.

Image: White Leghorns, courtesy Wikipedia

Published on August 17, 2016 21:30

August 15, 2016

From the Archives: The Tale of a Teenaged Sailor (and Embroiderer), 1850

Isabella reporting:

Isabella reporting:Not all 19thc embroidery was done by ladies in parlors. This sailor's uniform and sea bag were featured in one of my favorite exhibitions at

Winterthur, now nearly five years ago. With Cunning Needle: Four Centuries of Embroidery was filled with stunning needlework that ranged from schoolgirl samplers to masterpieces by professional embroiderers. While some of the pieces might have represent more skill or sophistication than the two pieces shown here, none had a better story behind them. (Click on the photos to enlarge them to see the details.)

Standardized uniforms for enlisted sailors in the United State Navy were still a relatively new notion in the 1840s-50s, when this uniform was created. While sailors were required to wear the Navy-issued uniforms while on board ship, there was more leeway in what they could wear on shore. The shore-going uniform could be proudly embellished and embroidered to suit a sailor's tastes, as well as to reflect his skill with a needle. ( Here's part of another elaborately embroidered shore-going uniform, a dark wool blouse from c. 1862.)

This rare summer uniform and sea bar were owned, worn, and likely embroidered by Warren Opie, born in 1835. Growing up in a large family of comfortable means in Burlington, NJ, Warren's childhood effectively ended with his cordwainer (shoemaker) father's early death in 1848. Warren's mother struggled to support the family, and several of Warren's sisters were sent to live with other relatives. It's likely that Warren, too, felt the family's financial pressures, and in 1850, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy for a three-year tour of duty with the rating of a second-class boy. He was fifteen.

Warren served on the steam frigate Susquehanna, the flagship of the four-ship squadron commanded by Commodore Matthew Perry on his historic trip to Japan between 1850-1854. Warren would have had considerable time to make this sea bag and uniform on the long voyage between Norfolk, VA and Japan; it's possible that he learned to sew from his father, or perhaps from some of the other men in the crew. While the uniform shows the typical patriotic motifs – stars, eagles, anchors, and flags – popular among sailors, his bag features his parents, his two closest sisters, and landmarks from his hometown in New Jersey. Warren was visiting exotic countries on the far side of the world, but it's clear his heart still remained at home.

In Japan, Commodore Perry presented a letter from President Millard Fillmore to the ruler of Japan in an elaborate ceremony involving nearly all the American sailors in his squadron and thousands of Japanese officials, soldiers, and attendants. Records show that one of the American ship's boys carried the president's framed letter in the procession. It's tempting to imagine Warren, dressed in this splendidly embroidered summer-uniform, as the boy performing this important task.

Unfortunately, there's no documentation to tell what became of Warren after his three-year-tour was done; he last appears in navy records as having been promoted to "landsman," a full member of the crew. No one knows if he died at sea, or jumped ship in some foreign port, or returned to New Jersey to live a long and contented life, nor is there any record of how his uniform landed in the hands of the dealer who sold it to Mr. Du Pont for his collection. It's all another history-mystery – but what a wonderful legacy Warren Opie left in his embroidery!

Above: Summer uniform of an enlisted sailor, worn by Warren Opie, 1850-54, linen, silk, wool.

Sea Bag, owned by Warren Opie, 1850-54, linen, silk, wool, cotton.

From collection of Winterthur Museum, Garden, & Library

Published on August 15, 2016 21:00

August 14, 2016

From the Archives: Matrimonial Disputes in the Early 1800s

Doctors Commons

Loretta reports:

Doctors Commons

Loretta reports:[Note: Because a couple of my English readers have asked about my letting characters get married at home, rather than in church, I thought I'd rerun this. In the not-too-distant future, I hope to go into the matter of special licenses in more detail.]

The matter of divorce in England in the early 19th century is much too complicated for me to attempt in a post. I’m not sure I’d attempt it in a dissertation. However, since we historical romance authors often send our characters to Doctors Commons for this, that, or the other thing, I thought I’d offer a Rowlandson image from the Microcosm of London and an excerpt describing one of its matrimonial functions.

Doctors Commons-matrimonial

Doctors Commons-matrimonial

This is also the place we’d send our heroes to obtain the famous-in-Regency-novels special license, which is explained in the epigraph heading the epilogue of Vixen in Velvet :

"But by special licence or dispensation from the Archbishop of Canterbury, Marriages, especially of persons of quality, are frequently in their own houses, out of canonical hours, in the evening, and often solemnized by others in other churches than where one of the parties lives, and out of time of divine service, &c."— The Law Dictionary 1810

The image I’ve used is courtesy Wikipedia, because it’s of superior quality to the one in the Internet Archive version. You can see truly splendid images from the Microcosm at the Spitalfields Life blog.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on August 14, 2016 21:30

August 13, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of August 8, 2016

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• American vacations of the early 1900s in color.

• London's westward expansion in the 18thc and the development of Mayfair .

• Celebrating Elizabeth Siddal , Pre-Raphaelite artist, poet, model, and muse.

• A charming 1920s " autograph quilt " from the Pink Granite Grange, New Hampshire.

• "Girls bowled, batted, ran, and catched": yes, women's cricket was played in the 1700s.

• Free to read online: rare novels and plays by women writers, 1600-1830, from the Chawton House Library.

• Image: One hundred years ago, Wyoming guardsmen stage a protest in Cheyenne by marching in nothing but their underwear .

• How exhaustion became a status symbol.

• Charlotte Cushman, a star of the stage who demanded equal pay - in the 19thc.

• Napoleon's remarkable porcelain " cabaret set " - a 36-piece breakfast service decorated with scenes of Egypt, 1810.

• Syphilis onstage: Eugene Brieux's 1913 play Damaged Goods brought a taboo subject into the limelight.

• English rose: cosmetics in 18thc England.

• Image: How cooking has changed - recommended boiling (!) times for vegetables and seafood, 1922.

• Five female coders that changed the world.

• Blessing cars and eating oysters: celebrating the saints' days of St. Christopher and St. James .

• The language of 18thc politics .

• George Washington writes to his step-granddaughter with advice for a happy marriage: companionship is more important than passion.

• "Have mercy on your dear child ," 1818.

• Image: Victorian mourning ring mounted with the glass eye of the deceased.

• An interview with Tracey Panek , the official historian of denim for Levi Strauss & Co.

• True colors: light damage and historic needlework .

• The forgotten wife of Charles Dickens.

• Ambire , an antidote against all sorts of poisons, from the New Kingdom of Granada, c1628.

• The 1880 police raid on the notorious cross-dressing ball at Temperance Hall.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on August 13, 2016 14:00

August 11, 2016

Friday Video: Messages from Roman Era London

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:After watching a video program like this one, observing the painstaking work involved in reading what amounts to ghost messages, I ought to hesitate to call myself a Nerdy History Girl, but I won't. These really are ghost messages, since they're only the shadows of the originals, unlike an inscription on a monument, say. But you do have to be a history nerd to get excited about the first use of "London"—and the surprising recovery of London after Boudica .

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post.

Published on August 11, 2016 21:30

August 10, 2016

The Importance of Mending, c1775

Isabella reporting,

Isabella reporting,We've often shared beautiful clothing here on the blog, lavish silk gowns enhanced with yards of lace and ribbons. For most women living in the 18thc, however, gowns like those were as far beyond their wardrobes as haute couture Chanel is for the majority of us today.

But our 18thc sisters valued the garments that they did own much more than we do. The cost of their clothing lay in the fabric, not the labor. Last year's clothes weren't discarded when they no longer fit, fell from fashion, or showed wear. Instead they were unpicked and taken apart and remade, mended and reworked. While the more expensive dresses would be remade by professional seamstresses and mantua-makers (see examples here and here ), most mending was done at home.

Girls were taught useful darning and mending stitches as well as fancy embroidery, and though it was often called "plain sewing," the neatness of the stitches and repairs represented a skill that was anything but plain. Nor was mending an entirely feminine endeavor. Men whose work took them far from home (and thus far from obliging female family members) like sailors and frontiersmen also became adept at mending their clothing.

I was reminded of the importance of mending as I recently watched Sarah Woodyard, a journeywoman mantua-maker in the Margaret Hunter shop, Colonial Williamsburg , repairing a gown. Sarah made the gown in 2012 for apprentice blacksmith Aislinn Lewis. (See the dress when it was new in this blog post .) The fabric is a serviceable linen with indigo-blue stripes, and it's the fabric that marks this as a working-class garment. With its open-front, fitted bodice and full skirts thanks to neat rows of tiny pleats, the same style of the dress could have been made in silk for a wealthy lady.

Aislinn's work at the anvil in the blacksmith's shop has worn sizable holes in the bodice and in the underside of the sleeve where the two areas rub together. Since the rest of the dress was still in good shape, Sarah offered to mend the holes. The goal of an 18thc patch or darn was to make it as unobtrusive as possible. Statement-making patches of contrasting fabrics wouldn't even have been considered. (The checked fabric that shows in the hole of the sleeve is the sleeve's lining, not a patch.)

In the photograph, above, Sarah is patching the hole in the bodice with a scrap of the original fabric, taking care to line up the stripes; the only difference will be how the new fabric hasn't faded. She'll turn in the raw edges and overcast them, and stitch everything neatly into place. The finished effect won't be invisible, but it will give fresh life to a favorite garment - not such a bad idea in our era of fast fashion and disposable clothes.

Photograph ©2016 Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on August 10, 2016 21:00

August 8, 2016

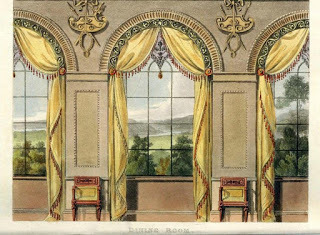

Dining Room Window Decor for August 1816

Dining Room Curtains August 1816

Loretta reports:

Dining Room Curtains August 1816

Loretta reports:The commentary about curtains and other hangings being used “in so liberal a degree” had me wondering whether this had been a recent fad, rather than the old-fashioned look of a previous generation. We do know that the heavily-draped look suited many Victorians, but I was puzzled about its popularity during the Regency. It’s also possible, though, that Ackermann’s Repository is simply explaining what’s tasteful and what isn’t, and casually directing the (upper class) reader to George Bullock, an important purveyor of furnishings during this period.

In any case, the view is nice.

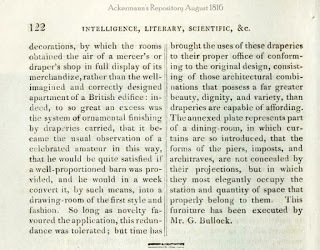

1816 Curtains description

1816 Curtains description

1816 Curtains description cont'd

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

1816 Curtains description cont'd

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on August 08, 2016 21:30

August 7, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of September 5, 2016

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Did Regency ladies ever get sunburned ?

• The surgeon's porcupine , c1830.

• The teen-aged midshipman was also His Royal Highness Prince William , and the first British royal to visit North America, 1781.

• So cool: see the reading habits of Aaron Burr, others, by searching the books they borrowed from the New York Society Library.

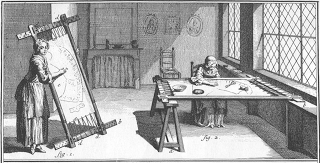

• Transferring designs for embroidery in the 18thc.

• The Book of Sir Thomas More: Shakespeare's only surviving • When ancient Romans had their clothes stolen, they responded with curse tablets.

• Image: Sarah Bankes boldly wrote her name in the front of her book, 1649.

• Inside the 300 year old model of St. Paul's.

• Scrapbooking Waterloo: Thomas Pickstock's travel journal, 1843.

• Caleb Brewster crosses the Devil's Belt: secrets of the Culper Ring, a Revolutionary War spy ring.

• Women in 1066: the power behind the throne.

• "Under cross-examination, she fainted": sexual crime and swooning in the Victorian courtroom.

• Image: Patchwork quilt featuring a stunning collection of printed dress cottons, 1820-1840

• The case of the "Ghost Sculptor", 1883.

• How Alexander Hamilton (and other 18thc Americans) did breakfast.

• Elected in 1887, Susanna Salter was the first female mayor in the US.

• Dogs in the 19thc press.

• Video: Check out these bicorn hats from the Museum of London.

• The history behind eleven exotic words from the world of fashion.

• Mud, blood, and vegetables: the soldier "farmers" of World War One.

• Plain work and stolen finery, 1837.

• Vive la comfort! For corseted 18thc courtiers, this dress was a French revolution.

• Image: What was on the menu for a BBQ in Portsmouth, RI in 1766?

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on August 07, 2016 19:34

Embroidery for a Man's Suit that Was Never Made Up, c1780

Isabella reported,

Isabella reported,Last month I visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Antonio Ratti Textile Center and Reference Library to study examples of 18thc embroidery (see my first post here), including this fascinating example. As always, please click on the images to enlarge them.

This piece is really several pieces, or panels, featuring the embroidered elements for a man's suit that was never completed. Elaborate embroidery was the height of male fashion in the 18thc, and skilled embroiderers executed designs in silk, sequins, and beading.

The embroidery was worked flat, with the fabric stretched taut on wooden frames. The embroidery pattern and the garment's outline were transferred to the fabric via pouncing - a light chalky powder pressed through tiny holes in the paper pattern - and then the lines were reinforced with ink on the fabric. These lines were meant to be covered by the embroidery, although some do still peek through if you look carefully. The illustration from Diderot's Encyclopédie, upper right, shows two embroiderers at work on a coat.

These panels are embroidered in silk thread, with accents of netting, on a purple silk cloth. The larger panel, left, includes not only the embroidery for accenting the front of the coat, but also the pocket flaps, upper left, and buttons, bottom left. The second panel, lower right, has the collar and cuffs as well as the knee tabs for the matching breeches. (To better understand how all these puzzle-pieces were meant to be assembled, see this similar suit, also in the Met's collection.) The pieces that are basted together in the second panel may indicate that different embroiderers were working on the same project.

In most cases, the completed embroidered panels would have next gone to a tailor to be made up into a suit. The embroidery could have been ordered to the tastes of a specific customer, or done on speculation. Either way, it would have been the tailor's responsibility to assemble the embroidery to fit his customer's body.

These panels were never made into finished garments, and the reasons why are now forgotten. They're rare survivors of the historic fashion trades, and wonderful to study as they are. But being a fiction writer, however, I kept wondering why the suit was never made. Were the colors of the silk flowers not to a customer's tastes? Was the embroidery more expensive than he expected, and never claimed? Or was the embroidery somehow "so last year," and out of fashion before it could be finished?

Many thanks to Melinda Watt, Associate Curator, European Sculpture & Decorate Arts, and Supervising Curator, Antonio Ratti Textile Center, and the staff of the Antonio Ratti Textile Center for their assistance, knowledge, and patience - as you can tell, I had a wonderful Nerdy-History-Girl time!

Many thanks to Melinda Watt, Associate Curator, European Sculpture & Decorate Arts, and Supervising Curator, Antonio Ratti Textile Center, and the staff of the Antonio Ratti Textile Center for their assistance, knowledge, and patience - as you can tell, I had a wonderful Nerdy-History-Girl time!Above: Embroidered panels for a man's suit, French, c1780, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photographs ©2016 by Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on August 07, 2016 18:58

August 6, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of August 1, 2016

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Victorian fat-shaming : harsh words on weight from the 19thc.

• How the stethoscope transformed medicine 200 years ago.

• Those kids of 1818, staring mindlessly into their glass devices: the now-forgotten craze for kaleidoscopes .

• The floating pleasure worlds of Paris and Edo in art.

• Jane Austen's music collection is now digitized and available on line.

• Image: Timeless beauty: a German gaming pouch , c1675-1700.

• Carved skeletons, Elizabethan theater giants, and a cat: St Leonard's , Shoreditch, London.

• Eleanor Sidgwick , the original Victorian female ghostbuster.

• Spectators pictured "fanning" the flames of early baseball passion.

• A history of embarrassing presidential campaign logos .

• Image: Celebrate summer's lushness with this green brocade robe a la francaise , c1740s.

• In 1704, Isaac Newton predicted the world will end in 2060.

• Willa B. Brown, the first African American woman to earn a commercial pilot's license in 1937.

• Ghosts in the machine: the devices and daring mediums that spoke for the dead.

• Discovery of vast treasure-trove of fine textiles shows importance of fashion to Bronze Age Britons .

• The history of exhaustion .

• Image: "Is this you five years from now?" Advertisement selling cigarettes to women as a diet aid, 1920s.

• The art of cuisine: dining with the artist Toulouse-Lautrec and his wildly impractical but fascinating cookbook.

• Working in the Paris fashion industry 100 years ago.

• Analysis of an athlete's weight, pains, digestion, perspiration levels, and speed - in 1813.

• A now-lost 1820s house in New York once known as the " house of romance. "

• Thomson's Guide to London , 1902.

• Seventeenth century doll houses weren't invented for children's play, but to show off wealth and teach domestic roles.

• Just for fun: Test your book smarts .

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on August 06, 2016 14:00