Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 51

August 4, 2016

Friday Video: A Miser's Purse, c1870

Isabella reporting,

Long before credit cards and Apple Pay, a miser's purse was the way thrifty shoppers kept their money sorted. Despite their name, miser's purses were a fashionable accessory and popular gift. Frequently mentioned in 19thc novels and women's magazines, the purses were also a favorite small handicraft project for ladies who enjoyed crochet and fancy beading. Today they turn up at flea markets, as sad and limp as old balloons, and likely unrecognizable to most modern shoppers. This brief video from the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum will remedy that, however, and explain how you didn't have to be a miser to use a miser's purse.

To see more examples of miser's purses in the Cooper-Hewitt collection, see here . For more information, the Museum has published a short ebook on miser's purses as part of their DesignFile line. The book was written by the narrator of this video, Laura Camerlengo, a Curatorial Fellow at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; it's available to download from Amazon here, and from Barnes & Noble here.

If you have received this video via email, you may see an empty space or black box where the video should be. Please click here to view the video.

Published on August 04, 2016 21:00

August 3, 2016

Fashions for August 1872

Walking dresses August 1872

Loretta reports:

Walking dresses August 1872

Loretta reports:According to Cunnington's English Women's Clothing in the Nineteenth Century , “The fashions of this year were marked by a change in the colour taste and a development of the polonaise.” While some “still clung to the use of two approximate shades of one colour ... others boldly employed contrasts, but the general preference was for soft and ‘autumn tints.’”

The polonaise “consisted of a bodice and tunic in one, the tunic being looped up at the sides, short in front and much looped up behind into a puff. It was, of course, only a revival of an eighteenth century garment but its acceptance may be fairly attributed to English rather than to French taste. In a special form, made with materials printed in chintz patterns, it was known as the ‘Dolly Varden.’ ” It seems we are not to use the two terms interchangeably, however, as, according to Cunnington’s sources, the Dolly Varden was “not patronized by the ‘best people.’” In other words, it was popular and affordable.

1872 dress description

1872 dress description

1872 dress description cont'd

1872 dress description cont'd

Cunnington includes more detailed explanations of the style(s). Since I do not make historical clothing and barely understand even modern dressmaking terminology, these might as well have been written in Romanian or Chinese. What’s clear enough is the change in shape from the 1860s fashions I showed last month , from the wide-all-around tent-like skirt to the flat front, and the wonderfully inventive emphasis on the booty.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on August 03, 2016 21:30

August 1, 2016

Trying to Keep Cool the 18thc Way in Colonial Williamsburg

Isabella reporting,

Isabella reporting,This past weekend I made a quick visit to Colonial Williamsburg, where it was hot, hot, hot, and tropically humid, too - the steamiest of Tidewater Virginia weather. As I walked (no, I'll be honest: I was dragging myself) around the historic area, I was impressed by how the women dressed in the style of c1775 seemed to look much more comfortable with the heat than I was, dressed c2016.

The secret to keeping bearably cool in the heat like our 18thc counterparts did? Apparently it's layers of linen and cotton that breathe and absorb perspiration away from the skin, plus straw hats against the sun.

Not far from the cabinet-maker's shop, Katy, upper left, was making a length of cord (probably destined for use as a drawstring) with the help of a lyre-shaped tool called a lucet. Her linen bedgown is comfortably loose and pinned closed, and given shape with the apron tied around her waist.

Sitting before the George Wythe House, Christian, right, was writing in her journal, pen in hand and inkstand on the bench beside her. In addition to her linen jacket, shift, and petticoat, she was wisely keeping from the sun with her wide-brimmed hat plus fingerless linen mitts, all designed to preserve a proper lady-like paleness.

In the shade of the courthouse porch, Mairin, lower left, was embroidering, her scissors hanging ready on a ribbon from her waist. She wore a mix of bright colors and prints that were cheerful and summery to modern eyes: a printed cotton short gown, a printed cotton neckerchief, a checked apron, and a bright yellow linen petticoat. In the shade, she didn't wear a straw hat, but she did make sure to keep her head covered with a neat linen cap. What 18thc woman wouldn't?

But all of these women were sitting still while they worked. The young women (I'm sorry I wasn't able to ask their names), below right, were working in the treading pit in the brickyard. With their feet bare and their petticoats tucked into their aprons, they took turns mixing water with clay to create the raw material for the brickmaker to mold into bricks. Visitors were invited to join them, shedding their shoes and sandals to take a turn in the treading pit and shrieking at the unfamiliar sensation of wet clay between the toes.

Beneath a tent-like shelter overhead against the sun - I suspect more to keep the clay from drying out than to protect the workers - the clay and water must have been pleasantly cool underfoot on this hot day. But passing visitors notwithstanding, this wasn't at all the romanticized, genteel way we often imagine the past. This was hard, tedious work, unskilled labor at its most basic, and I couldn't help but think of the 18thc women, men, and children who must have toiled in similar treading pits from dawn until dusk, from early spring until the frosts of fall - and likely for the most minimum of wages, too.

All photographs ©2016 by Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on August 01, 2016 21:00

July 31, 2016

Opening the New London Bridge, August 1831

London Bridge 1 August 1831

London Bridge 1 August 1831

Loretta reports:

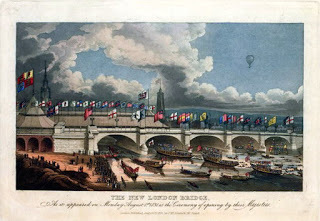

Usually, I start the month with fashion plates, but today’s the 185th anniversary of the opening of the “new” London Bridge. So we'll look at that instead, in pictures and text, since it isn't in London anymore.

The bridge, as many are aware, has had several incarnations .

On this day in 1831, King William IV officially opened, with great pomp and ceremony, the version that’s since moved—more or less—to Arizona.

You can read a short summary of its life here, and a lengthy account in the Gentleman’s Magazine starting here .

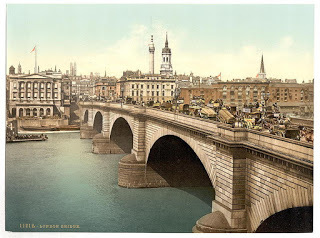

London Bridge ca 1890-1900

You may not feel up to an early 19th century detailed report on the bridge’s history and construction, along with a blow-by-blow description of the opening ceremony. These lengthy accounts are tough on modern readers. But this sort of thing was what readers wanted, in the days before photography, let alone television. If the whole article is too much for you, you might still want to take a look at the very nice bird’s eye view engraving

here

.

London Bridge ca 1890-1900

You may not feel up to an early 19th century detailed report on the bridge’s history and construction, along with a blow-by-blow description of the opening ceremony. These lengthy accounts are tough on modern readers. But this sort of thing was what readers wanted, in the days before photography, let alone television. If the whole article is too much for you, you might still want to take a look at the very nice bird’s eye view engraving

here

.Image above left: The New London Bridge as it appeared on Monday August 1st, 1831, at the Ceremony of opening by their Majesties, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

Below right: London Bridge ca 1890-1900 , courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on July 31, 2016 21:30

July 30, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of July 25, 2016

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• The parachute wedding dresses of World War Two brides.

• Winged skulls and hot air balloons: the unusual grave of Etienne-Gaspard Robert , pioneer of phantasmagoria.

• What's in my bag, 1890s Montreal edition.

• Speculating about the appearance of Elizabeth I through dress reconstruction.

• Let them eat stale bread: the diet of the poor in Regency England.

• Image: Scrap album fancy dress , 1893.

• Victorian and Edwardian lingerie pin-ups.

• While John Adams was in Philadelphia in 1776, Abigail Adams wrote this letter to him with news of having their children (and herself) inoculated against smallpox.

• Canines and crinolines: Victorian dogs confined by fashion.

• Image: A 17thc recipe for "an approved Elixir for the recovery of health in those that have longe languished."

• A 1936 junior miss suit with a lot to say.

• Read this 1891 booklet online: Don't Marry; or, Advice as to Who, How, and When to Marry.

• George Washington's favorite horse, Nelson.

• The children of World War One in photographs .

• The mirrors (or not) behind Rembrandt's self-portraits .

• The high cost of life for Europeans in India .

• New York man finds enslaved ancestor's bill of sale, 220 years ago.

• Image: Author Charlotte Bronte was only 4'10". Here's her bodice and her gloves .

• Modish dresses , modesty, and Napoleon's brother, 1815.

• How a Dutch fabric-maker became the father of microbiology .

• Nathaniel Hawthorne and the Fountain of Youth .

• The first Indian restaurant in London, 1810.

• Dress made from World War Two silk escape maps .

• Who was luckiest in the American Revolution?

• Just for fun: An oldie but goodie: copywriter proofreading marks explained.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on July 30, 2016 14:00

July 28, 2016

Friday Video: The Singing Bird Pistols & Their Restoration

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Readers familiar with my short story, “Lord Lovedon’s Duel,” (from the Royally Ever After duet) will remember the Singing Bird Pistols. I’ve shown the pistols in operation in a previous blog . What I didn’t realize was how much restoration work went into making them look like this .

Today's video tells the incredible story of that restoration (you may have to overlook the highly energetic introduction & music).

You can watch the same program without the noisy TV intro here on Vimeo .

In both cases, you will notice some odd spelling in the subtitles. Ever wonder how this happens? I sure do. Hello? Dictionary?

Many thanks to reader Kafryn W Lieder for sending me the link!

Many thanks to reader Kafryn W Lieder for sending me the link!Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post.

Published on July 28, 2016 21:30

July 27, 2016

When a Victorian Painting Isn't What It Seems

Isabella reporting,

Some of the most popular 19thc painters were storytellers as well as artists, filling their realistic canvases with characters and symbolism that gallery-goers of the time could "read" as clearly as if the paintings were books. Poignant farewells, heroic soldiers , thwarted lovers, fallen women , scenes from history and from current events all found their place in these often-oversized, detailed paintings.

When I recently came across the painting, above, on Twitter, I was sure I understood the story it told. Even the title with its Biblical quotation seemed filled with obvious meaning: Nameless and Friendless: "The rich man's wealth is his strong city" - Proverbs X, 15. (As always, please click on the image to enlarge it.) Painted by Emily Mary Osborn in 1857, I thought it must be a poignant representation of a young widow forced to sell her belongings to survive. Her somber clothes must be a stage of mourning, and her melancholy expression hints at painful memories of happier times. Perhaps the painting that the gallery owner is appraising was even a favorite of her late husband.

And wow, was I ever wrong.

To learn the real subject of this painting, go to

But before you go over there - what do you see in this painting?

Above: Nameless and Friendless: "The rich man's wealth is his strong city" - Proverbs X, 15 by Emily Mary Osborn, 1857, The Tate.

Published on July 27, 2016 21:00

July 25, 2016

Traveling Advice & Expenses 1828

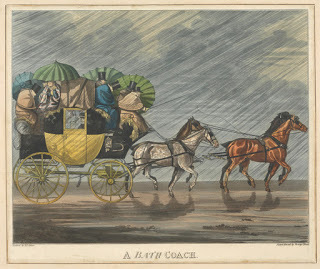

Alken, Bath Coach 1820

Loretta reports:

Alken, Bath Coach 1820

Loretta reports:Traveling in the early 1800s was complicated to a degree we can scarcely fathom. The Traveller's Oracle , by William Kitchiner, M.D., deals with what seems to be every last, daunting detail of the process, like what sort of servant(s) to take, what medicines to pack, how to sleep safely at an inn, and so on.

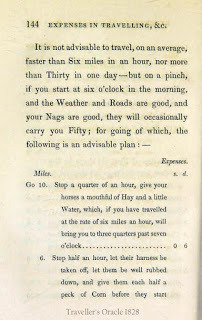

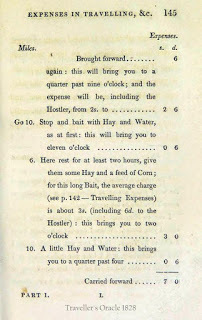

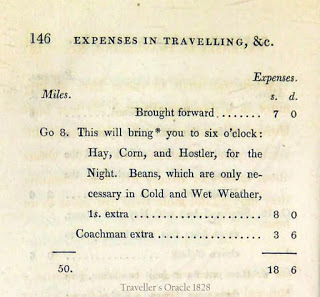

I could have picked any of dozens of excerpts, but decided matters of the horse would offer a good clue to the kinds of things one had to consider. This is from the third (1828) edition:

Travel expenses

Travel expenses

Travel expenses

Travel expenses

Travel Expenses

Travel Expenses

When you wish to travel forty or fifty miles in a day expeditiously, if you have Horses of of your own—it is the most advisable plan to send them on the day before about twenty or twenty-five miles, desiring they may go not more than five miles in an hour.Image: Henry Alken, Bath Coach (1820) courtesy Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

If you start from home with post Horses, your own will be fresh to carry you on briskly to the termination of your Journey.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on July 25, 2016 21:30

July 24, 2016

A Close Encounter with Silk Embroidery for an 18thc Gentleman's Suit

Isabella reporting,

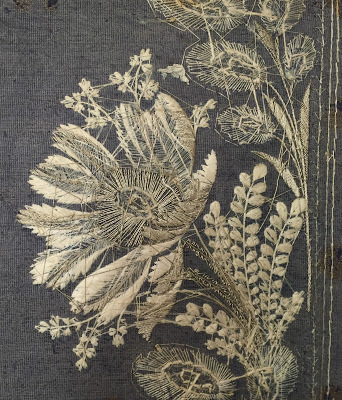

Isabella reporting,One of my favorite textile/costume exhibitions was last summer's Elaborate Embroidery: Fabrics for Menswear before 1815 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (you can read my post about it here .)

But as wonderful as the exhibition was, I longed to see the richly embroidered samples more closely than the display cases permitted. Last week, I finally returned to the Met for a research appointment at the Antonio Ratti Textile Center and Reference Library - the keepers of all those embroidery samples and much, much more besides.

The sample here (click on the images to enlarge) was one of the ones that I requested to view. It's not large: 12-1/2" x 7-3/4". The black fabric is faintly dotted silk velvet, and the embroidery threads are silk and metallic. There are also dozens of tiny sequins as well as paste jewels worked into the design. It might have been a sample of an embroidery pattern that was shown to gentlemen considering new suits, or it could also have been a experiment with a new pattern. The sample eventually became part of the textile design archives of The United Piece Dye Works, who gave the collection to the museum in 1936.

This sample was stitched in France around 1800-1815, long past the time when Louis XVI's court and their legendary excess had been displaced by the Revolution. But Napoleon Bonaparte liked those same sartorial trappings as much as his royal predecessors had, and gentlemen appearing at the imperial court were expected to appear in suits of luxurious fabrics embellished with embroidery like this. Of course, this kind of elaborate formal dress had never stopped being worn at the English court and others like it across Europe, but these suits were to be the last gasp of the glittering male peacock. Within a generation, formal wear for gentleman became dark and subdued, and has remained so to the present day.

Worked in shades of silver with gold accents on that inky velvet, a suit enhanced with the design in this sample would have sparkled and gleamed in an elegant, refined show of wealth and taste. Equipped with a magnifying glass, I was able to see the exquisite delicacy of the stitches, and the extremely fine silk and metallic threads used to create them, threads that would likely be impossible to find today.

I was especially interested in the tiny sequins, held in place by even smaller beads. The sequins that were stitched directly onto the velvet had tarnished over time, probably from a dye in the velvet, giving them an unintentional ombre effect. The small paste (glass) "jewels" near the edge were secured in in metal collars, which in turn were hidden by a loop of wrapped metallic thread. These details are visible where some of the loops has slipped away from the jewel.

I also loved being able to see the back side of the embroidery. Without the pile of the velvet and the glitter of the sequins and jewels, the design becomes more linear with the transition stitches criss-crossing over the flowers and leaves. In a way, it's equally beautiful, like the finest of silk spiderwebs.

Most of all, seeing this sample in such detail left me in awe of those now-forgotten designers, embroiderers, thread-spinners, sequin-and paste-jewel makers, velvet-weavers, and needle-makers who would have each contributed to its creation, and the skill, artistry, and accomplishment that this small bit of two-hundred-year-old fabric represents.

Many thanks to Melinda Watt, Associate Curator, European Sculpture & Decorate Arts, and Supervising Curator, Antonio Ratti Textile Center, and the staff of the Antonio Ratti Textile Center for their assistance, knowledge, and patience - as you can tell, I had a wonderful Nerdy-History-Girl time!

Above: Embroidery sample for a man's suit, French, 1800-1815, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Photographs ©2016 by Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on July 24, 2016 18:44

July 23, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of July 18, 2016

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• How the corset turned into a girdle, 1900-1919.

• The now-forgotten " girl mayors " of the 1920s became the first face of feminism.

• Keeping khaki-kool during World War One.

• Baunscheidt's Lebenswecker: the 19thc " life-awakener " (and now considered fraudlent.)

• The peculiar history of cows in the OED.

• Video: Short video of magnificently embroidered early 20thc evening dress .

• The (almost lost) art of handwriting .

• How and when did the thirteen colonies learn of the Declaration of Independence ?

• Image: 19thc purse made from hundreds of melon seeds.

• Magical photographs of fireflies in Japan.

• The rich and fascinating history of dhaka muslin .

• Ten strangest deaths of Roman emperors .

• Descendants of a South Carolina plantation owner and slaves unite to have dinner together 181 years later.

• The 18thc anatomist who celebrated life with dioramas of death.

• Image: Photographer Margaret Bourke-White sets up camera on a gargoyle on the 61st floor of the Chrysler Building, 1934.

• Cleopatra's Needle : how an Egyptian obelisk ended up by the Thames.

• "An extraordinary delivery of rabbits": how Mary Tofts convinced doctors she'd given birth to rabbits, 1726.

• Creating La Dolce Vita in post-war Italy.

• The surprisingly raucous home life of James and Dolley Madison .

• Why women led anti-suffrage movements against themselves.

• Silk-dyers in 18thc London.

• Image: Women's day at the free public bathing house in the East River, NYC, 1876.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on July 23, 2016 14:00