Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 46

October 26, 2016

London in October in 1826

Loretta reports:

I discovered Peter George Patmore’s Mirror of the Months through Hone’s Every-day Book, which quoted from the excerpt below. Rather more readable than many writers of the time, Patmore vividly describes the sights and sounds of England, town and country, during each month of the year. He offers some insights into society—with lower case as well as capital S—as well as painting some charming domestic scenes, like this one. Anybody who’s been in London in the autumn will relate, I’m sure.

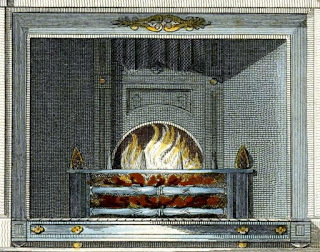

Images from Ackermann's Repository.

Images from Ackermann's Repository.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it.

I discovered Peter George Patmore’s Mirror of the Months through Hone’s Every-day Book, which quoted from the excerpt below. Rather more readable than many writers of the time, Patmore vividly describes the sights and sounds of England, town and country, during each month of the year. He offers some insights into society—with lower case as well as capital S—as well as painting some charming domestic scenes, like this one. Anybody who’s been in London in the autumn will relate, I’m sure.

“But has London no one positive merit in October, then? Yes; one it has, which half redeems all its delinquencies. In October, Fires have fairly gained possession of their places, and even greet us on coming down to breakfast in the morning. Of all the discomforts of that most comfortless period of the London year which is neither winter nor summer, the most unequivocal is that of its being too cold to be without a fire, and not cold enough to have one. At a season of this kind, to enter an English sitting-room, the very ideal of snugness and comfort in all other respects, but with a great gaping hiatus in one side of it, which makes it look like a pleasant face deprived of its best feature, is not to be thought of without feeling chilly. And as to filling up the deficiency by a set of polished fireirons, standing sentry beside a pile of dead coals imprisoned behind a row of glittering bars,—this, instead of mending the matter, makes it worse; inasmuch as it is better to look into an empty coffin, than to see the dead face of a friend in it. At the season in question, especially in the evening, one feels in a perpetual perplexity, whether to go out or stay at home; sit down or walk about; read, write, cast accounts, or call for the candle and go to bed. But let the fire be lighted, and all uncertainty is at an end, and we (or even one) may do any or all of these with equal satisfaction. In short, light but the fire, and you bring the Winter in at once; and what are twenty Summers, with all their sunshine (when they are gone), to one Winter, with its indoor sunshine of a sea-coal fire?”

Images from Ackermann's Repository.

Images from Ackermann's Repository.Clicking on the image will enlarge it.

Published on October 26, 2016 21:30

October 24, 2016

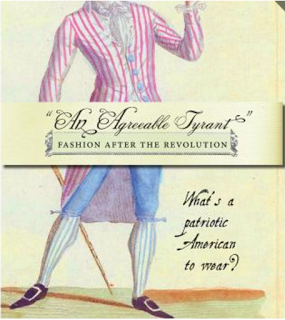

From the NHG Library: "An Agreeable Tyrant: Fashion After the Revolution"

Isabella reporting,

Isabella reporting,Loretta and I both have more research books crowding our respective houses than either of us would like to admit. Yet there's always room for one more, especially when that book fills an important gap on the shelf.

I'm currently working on a historical novel set in 18thc America during and after the Revolution. (That's all I'm saying for now - everything will be revealed soon enough, with a publication date of September, 2017.) It's a fascinating period in American history, with the dramatic achievements of the war giving way to the difficult process of not only building a new country from the ground up, but also creating a national identity to go with it.

Part of that new identity was deciding what Americans should wear. Of course, for many people this meant continuing to wear what they'd worn before the Revolution, but for more fashion-conscious Americans, this was a serious question. They wanted to continue to be as stylish as their counterparts in London and Paris, but they didn't want to follow the fashion dictates of the royal courts. Displaying taste and wealth would also be a challenge in homespun. As the subtitle of this new book asks: "What's a patriotic American to wear?"

An Agreeable Tyrant: Fashion After the Revolution, above, is a new companion book to an exhibition currently on display at the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum in Washington, D.C., through April 29, 2017. This beautifully written and designed book is much more than a mere exhibition catalogue, however. It contains dozens of full-color photographs of surviving garments - many shown on mannequins, complete with accessories, right - plus fashion plates, portraits, and other images from the era.

There are also thoughtful, informative essays written by experts in the field of historic fashion and textile, including lengthy footnotes to primary sources (be still my nerdy history heart!) Clothes for men and women of every class are covered, including enslaved people. And for readers who appreciate the "behind the seams" approach to fashion history, detailed, scaled patterns of garments complete the book. Congratulations to Alden O'Brien, Curator of Costumes & Textiles, DAR Museum, and her staff for creating such a wonderful book.

An Agreeable Tyrant deserves a place in every costume-lover's library, and on the shelves of American historians as well. And yes, it's an excellent resource for us fiction-writers. I've already referred to it to "dress" my characters, and I've given it the ultimate endorsement: I didn't receive this for review, but ordered it myself as soon as it was available.

If you're interested in purchasing a copy of An Agreeable Tyrant, you can order it directly from the DAR Museum's site here .

Above (left to right): Silk gauze dress, 1810; Purple silk dress, 1810; Silver brocaded evening dress, 1810s, all from a private collection. Photograph copyright DAR Museum.

Published on October 24, 2016 21:00

October 23, 2016

Naughty Watches of the 18th and 19th Centuries

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:At a recent authors event, readers asked about the naughty watch a character buys in my book Lord of Scoundrels : Was this based on research or imagination?

If you Google “erotic watches,” you’ll know I wasn’t making this stuff up. So yes, the idea came from research—done in the days before Google existed, I ought to point out. These days, it would have been easier.

While I was aware of snuff boxes with erotic scenes inside the lid, the pornographic watch was news to me. I was especially intrigued to learn that watchmakers had been creating these devices as early as the late 1700s. This includes Abraham-Louis Breguet, a famous, highly-regarded watchmaker mentioned in Lord of Scoundrels.

Eric Bruton’s The History of Clocks & Watches offers a black and white illustration of a carriage watch, from which I developed the one in my book.

“It shows the time, day, date, and sidereal time, strikes the hours and quarters, and plays tunes on six bells. On the back a human figure in three parts keeps changing and below it some ‘curtains’ can be drawn aside to reveal an animated pornographic scene.”The watch was made in London in 1790.

Though it’s not like the watch shown in The History of Clocks and Watches, this one works more or less the same way: an innocent front, with an animated scene on the other side. Googling the subject will bring you quite a few examples, including one on YouTube—but I'll let you search, if you wish. I'm trying to keep this post at least somewhat family-friendly.

Image (not erotic to my knowledge): Chevalier et cachet watch between 1790-1799 (gift of Liz and Peter Moser, 2006), courtesy Walters Art Museum.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on October 23, 2016 21:30

October 22, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of October 17, 2016

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• How London's Foundling Hospital defied " gruel stereotypes ."

• A 2,000 year old canister of ancient Roman face cream , including the finger marks of the user.

• Emily Brontë's homely life.

• Shades of Victorian fashion : lilacs, lavenders, plums, and purples.

• Black women , slavery, and the silences of the past.

• Image: Lovely, evocative autochrome photograph taken in Longwood Gardens, 1915.

• Male midwives and disobedient women in 18thc Britain.

• Ann Mead: the life and death of a teenaged nursemaid , 1800.

• Ominous illustrations of ventilation , 1869.

• Boston's Rat Day , 1917.

• Is this note passed between the lines at the Battle of Antietam stained with Civil War blood ?

• Image: Skilled needleworker Mary, Queen of Scots , embroidered this cat.

• George Washington's "racy" letter about a donkey goes on sale.

• Signs of old London.

• Designer Ann Lowe : how a little-known black pioneer changed fashion forever.

• Dance card from 1924 for an engineers' dance - check out the names of the dances!

• Famous illustrators depicting knitters and knitting - and here are some vintage photos of knitters , too.

• Image: Appalling early 20thc anti-suffragette poster.

• Before George Washington became a general or a president, he tried his hand at poetry, with mixed results.

• In search of the lost mosque of Kew Gardens.

• A 1950s version of Yelp? The Gustavademecum , a NYC dining guide for engineers and explorers.

• The beautiful English romantic painting of Samuel Palmer.

• Image: Little Egyptian faience model of a hedgehog , made around 1300-1500 BC.

• Following the geometry of fire in the National Archives.

• The lighter side of 15thc magic .

• Monuments to some of the world's most pawsome cats .

• The history of the rural cemetery movement , which brought Victorians to picnic among the gravestones.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on October 22, 2016 14:00

October 21, 2016

(Un) Dressing Mr. Darcy

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Writers as well as readers who’ve tried to work out the details of historical clothing generally appreciate a chance to see actual human beings wearing historically accurate attire.

Isabella and I have been fortunate in being able to call on the expertise of the tailors and milliners of Colonial Williamsburg . We’ve also posted what we’ve learned and seen there. Although I set my books in a later time period than the site focuses on, the historians there have The Knowledge of various eras, and have advised me on many points. But not everybody can consult with them while writing or reading a book. A demonstration like this one can answer a great many questions.

Though my current stories are later, too, than the time period recreated in this video, and the cut of coats and breeches/trousers change, as do hats, the principles apply.

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post.

Published on October 21, 2016 06:55

October 19, 2016

An Englishwoman's Abolitionist Statement, 1827

Isabella reporting,

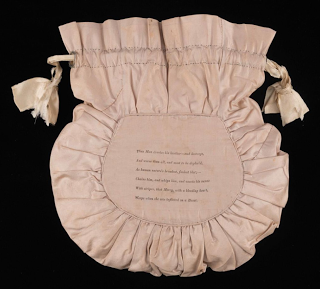

Isabella reporting,Today (especially during this election year) people wear a printed t-shirt to display their political allegiances and concerns to the world. In the 19thc, the abolition of slavery was an important and emotional social movement, and abolitionists found many ways to show their support their cause. Abolitionist motifs and slogans appeared on everything from jewelry to porcelain to printed scarves, handkerchiefs, and workbags like this one, newly acquired for the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

Although workbags originally were intended to carry a woman's sewing or embroidery (her "work"), by the 1820s they had become more general carry-alls for daily essentials, much like a modern purse. Most workbags were decorated with prettily embroidered patterns, but this one carried a more serious and somber message. Printed on the front is a copper plate image of an enslaved man in chains, while in the background others are being whipped by their master or overseer. Though this may seem somber for a lady's accessory, by the early 19thc the figure of a kneeling slave had become the unofficial symbol of the abolitionist cause.

A workbag like this was also viewed as a show of sympathy to the enslaved people themselves. While it might be considered improper or indelicate for a lady to become too deeply involved in a cause as sordid as abolition, it was acceptable for English ladies to demonstrate their emotional concern for those who suffered.

On the back of the workbag is printed an excerpt from William Cowper's 1784 poem on slavery, The Task:

"Thus man devotes his brother, and destroys;

And worse than all, and most to be deplored,

As human nature's broadest, foulest blot; ––

Chains him, and whips him, and exacts his sweat

With stripes, that Mercy, with a bleeding heart,

Weeps when she sees inflicted on a beast."

According to the collection's label:

"Established on April 8, 1825, the Birmingham, England, Female Society for the Relief of British Negro Slaves, produced literature, printed albums, purses and workbags [including this one] for sale to help raise awareness of the cruelty to enslaved Africans and to provide money for their relief. These women, many members of the Society of Friends or Quakers, began one of the earliest Free Labor Movements specifically against the purchase of slave-made West Indian sugar. Identical objects and literature crossed the Atlantic and helped to fuel the American abolitionist movement."

Many thanks to Neal Hurst, Associate Curator of Costume & Textile, Colonial Williamsburg, for sharing this with us.

Workbag, made by the Female Society for the Relief of British Negro Slaves, 1827. The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

Published on October 19, 2016 21:00

October 17, 2016

Forged Banknotes in the Regency Era

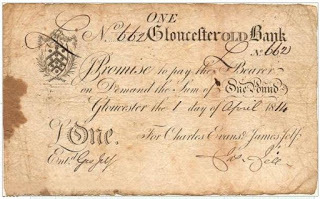

£1 Bank Note 1814

Loretta reports:

£1 Bank Note 1814

Loretta reports:In researching Dukes Prefer Blondes , I spent some time looking up criminal cases. I was struck by the number of prosecutions for coining and forgery. That was why the short entry (shown below) in Hone’s Every-day Book about forged notes caught my attention.

I found an explanation at The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674-1913.

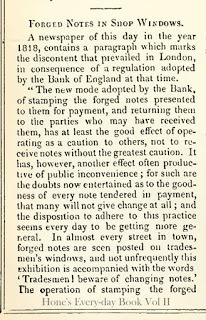

Forgeries 1818

Forgeries 1818

“Between 1797 and 1821, the period known as the ‘restriction’, new, primarily copper coins and, most importantly, inexpensively produced £1 and £2 notes were brought into circulation. The poor quality of these notes led to a spate of forgeries, which in turn led to a high number of prosecutions led by the Bank [of England] itself, for both forgery and uttering forged notes.”

If you’re curious about what old bank notes looked like, you can scroll down this page .

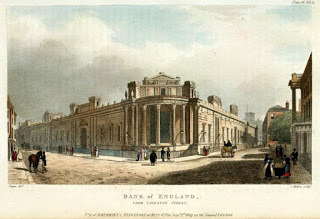

Bank of England 1809

Bank of England 1809

You can look at a forged note from 1936 here .

And the Old Bailey website also offers a history of money & what it bought .

Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on October 17, 2016 21:30

October 16, 2016

Ann Flower's Drawing Book, c1753-1760

Isabella reporting,

Isabella reporting,Sketchbooks are the notebooks of artists. They use them to explore influences, capture quick impressions, and save ideas for later work, all in (mostly) visual form. But like many notebooks, sketchbooks are often fragile, made of inexpensive paper that over time disintegrated, and often discarded by the artist her/himself, or tossed later after the artist's death.

Compared to Europe, there were relatively few artists in colonial America, and even fewer of their sketchbooks survive today. Only three are currently known: one each by John Singleton Copley and Benjamin West, and the one featured here by Ann Flower. Copley (1738-1815) and West (1738-1820) are prominent names in art history, men whose talent was encouraged and supported, and whose skill eventually carried them from the colonies to London and the celebrity of noble, even royal, patrons.

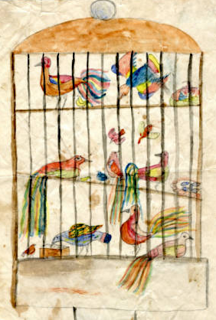

Ann Flower (1743-1778) was a Quaker woman from Philadelphia who would never have considered a career as a professional artist, or have travelled to Europe to pursue such a career. This modest sketchbook, or drawing book, and several pieces of her needlework are all that remain of her youthful creative spirit. It's believed to date from around 1753-1760, when Ann would have been an adolescent, living in the largest city of the American colonies.

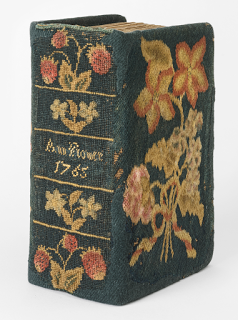

I saw Ann's sketchbook and her embroidered book cover, bottom right, as part of the Embroidery: The Language of Art exhibition currently at Winterthur Museum (see here and here for other posts I've written about this exhibition), and I learned more about her and her work at the Winterthur conference inspired by the exhibition this weekend. Amanda Isaac, Associate Curator, George Washington's Mount Vernon, has extensively studied Ann Flower and her work, and spoke about her drawing book as well as women's artistry in colonial Philadelphia.

Ann's sketchbook is small, only about 8" x 5" and made from fifteen sheets of paper. While it was purchased commercially, over time she tore some pages out, and added another. She drew in pencil and in ink, and added color with watercolor paints purchased from Philadelphia shops. The early pages of the book are filled with the kind of brightly colored, fanciful birds popular in 18thc embroidery, including a stupendous peacock, middle left, plus a rabbit, and a cat. Ann was a skilled needleworker, and it's possible she was experimenting with new designs or archiving older ones. There are also designs for flowers, vases, and animals.

But later in the book, Ann also drew from her life: pictures of Philadelphia women, middle right, detailing their dress, and a view of a house that may have been her own. (I particularly liked the thin black ribbons worn around the throat of one of the women that, according to Ms. Isaac, were a worldly fashion embraced by young Quaker women around 1760, and deplored by their elders - exactly the kind of thing that a teen-aged artist would note.) Fragments of faces in faded pencil peer from the pages, and more realistic drawings of flowers and birds were likely copied from botanical prints. Although untutored and unsophisticated, there's an undeniable energy to her drawings, and a quick eye for detail.

The final section of the sketchbook contains carefully inked patterns for embroidery, as well as colored drawings of flowers copied from a well-known 18thc book: Augustin Heckel's The Florist; An extensive and curious collection of Flowers/For the imitation of/Young Ladies,/Either in Drawings, or in Needlework. Ann's versions weren't literal copies of Heckel's work (so much for ladylike imitation), but her own interpretations. When she designed the embroidery for the book cover, she combined Heckel's flowers with her own to create a new design, a bouquet tied with curling ribbons, and clumps of strawberries on the spine.

The book cover is the last known example of Ann's needlework, and it likely must have held special significance for her. It covers a copy of the Anglican Church's Book of Common Prayer that was given to her by her father around the time of her marriage in 1765. Ann left the Quaker meeting to marry a man who was an Anglican, and the prayer book may have been her father's way of supporting her as she left her old faith behind. As Ms. Isaac suggested, the elaborately worked cover, too, may also been Ann's way of making her new religion and new life her own by surrounding it with familiar flowers and needlework.

While I know most of you won't be able to visit Wintherthur to see Ann Flower's sketchbook in person, the museum has made it available to read or download online here .

Many thanks to Amanda Isaac for sharing her research on Ann Flower.

Above: Illustrations from a Sketchbook, by Ann Flower, watercolor, pencil, and ink on paper, c1753-1760. Winterthur Museum.

Below: Embroidered Book Cover, by Ann Flower, wool and silk on linen, c1765. Winterthur Museum.

Published on October 16, 2016 18:40

October 15, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of October 10, 2016

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Doris Duke , the last Gilded Age socialite of Newport, RI.

• Bowled over at the 1927 Highland Park Bowl .

• Lord Woolton Pie : recipe and history of the much-mocked carrot pie created during wartime rationing and which might be worth trying today.

• Image: Chills: when you find something in an old book....

• Mad, bad, and dangerous to spar with: boxing with Byron .

• Was Florence Foster Jennings really the worst singer in the world?

• Postage due: the perils of American Civil War mail delivery.

• Nineteenth century children employed in dangerous trades.

• Image: This failed 1838 constitutional amendment would have forbidden duelists from holding public office.

• Work out like an Edwardian: read 1913 Physical Culture for Women online.

• The clothes! Wonderful photos of American department store workers , c1898-1900.

• Accidental explosions : gunpowder mishaps in Tudor and Stuart London.

• Image: At the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC, a librarian's tombstone that looks like a catalogue card.

• Huh: in 1875, someone published a novel with rivals "Trump" and "Clinton."

• Ten • Thomas Newington's recipes, 1715.

• The nearly-lost drawings of an artist who spent most of his life in an insane asylum.

• Image: Wouldn't you like to know more about Miss Macdonald, the inventress of this 1818 walking dress?

• Tape loom weaving and its traditions in colonial North America.

• Repetition is celebrity: Austen and Shakespeare.

• Combating the fear of "white slavery" in the 1930s: the FBI, sexual predators, and the Mann Act.

• Short video: It's just a box of old sewing supplies....

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on October 15, 2016 14:00

October 13, 2016

Friday Video from the Archives: A Glimpse Back to the Edwardian Past, c. 1900

Isabella reporting,

This isn't a single video, but a series of short, silent clips pieced together. The description notes that it's also been "enhanced," with the focus sharpened and the speed made consistent. That said, it's a wonderful slice of Edwardian life, a medley of street scenes, factory-dominated landscapes, amusement parks, family scenes, dockside farewells, and holidays at the beach. The caption on YouTube says the clips were mostly shot in London, with some perhaps from Cork, Ireland as well.

Much like one of our earlier Friday videos from 1895, the people here may have been arranged before the camera, but no one is acting. Seeing how everyone walks, how their clothes move and how they carry themselves, the carriages and wagons and early motor cars - it's as close as we'll get to being able to look backwards in time more than a hundred years.

Several things stood out to me while watching this:

1) Everyone dressed much more formally then, no matter what the occasion.

2) Boys and men have always been willing to stick their faces in front of a camera.

3) Wherever the people in the last scene are, it's an incredibly happy crowd. So many smiles!

4) The women's hats are fantastic, and so are the men's moustaches.

What do you see?

If you received this post via email, you may be seeing an empty space or black box where the video should be. Please click here to view the video.

Published on October 13, 2016 21:00