Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 44

December 3, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of November 28, 2016

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and the Hessians of the American Revolution.

• Edgar Degas and Miss LaLa at the Cirque Fernando.

• The • The dancing plague of 1518.

• Her Majesty has an eye-watering collection of miniature things.

• When Felix the Cat took down an airplane at the 1932 Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade.

• Image: Shakespeare in brick.

• That time when the mother-of-the-bride stole all the attention in a jeweled Byzantine gown designed by Worth.

• Whatever happened to Pre-Raphaelite model and muse Fanny Cornforth?

• Updated for modern cooks: a 17thc recipe for a marmalet of pippins (for those can't resist apples in season.)

• Image: 17thc gold and enamel memento mori ring, to remind the wearer of the brevity of life.

• Explore the life and reign of Elizabeth I in her own words.

• Guy Fawkes' lantern.

• How Charles Dickens kept a beloved pet cat alive (sort of.)

• Nicknames of the • Fashion is not a matter of size, except when it is.

• Image: Restraint clothing used at Bedlam Hospital in the early 19thc.

• Granddaughtes of the revolution: modern descendents of early suffragists recall the work of their ancestors.

• Now to read online: a 17thc registry of Scottish men and women accused of witchcraft.

• A Stuart prince reappears in Baltimore.

• The wayward youth of John Adams.

• "Her slip is always showing": Picky bosses and their pet peeves about their secretaries, 1945.

• Gambling, cheats, and Voltaire's Madame de Chatelet.

• Image: Just for fun: the only celebrity autograph worth having.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on December 03, 2016 14:00

December 1, 2016

Friday Video: Victorians Get Dressed Quickly

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Continuing the 2NHG tradition of re-examining aspects of history that might not be completely true and may in fact be completely false, I present for your consideration this interesting program in which a historical interpreter gets into her Victorian attire in a very short time.

This is the same expert, by the way, who demonstrated the many different activities a Victorian lady could perform while wearing a corset .

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post.

Published on December 01, 2016 21:30

November 30, 2016

Into the Writing Vortex with Jo March & Louisa May Alcott, 1869

Isabella reporting,

Isabella reporting,As Loretta and I have mentioned here before, we are each furiously racing towards our separate book deadlines. We commiserate with one another long distance (she's in Massachusetts, and I'm in Pennsylvania), but for the most part we're so deep in the writing morass that we're not very sociable.

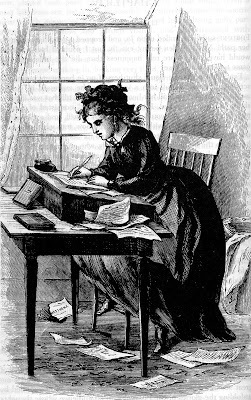

We're not alone in this, of course. Yes, writers write, but there is also much wailing and gnashing of teeth. That's why I love this particular passage from Little Women, the classic novel by Louisa May Alcott. First published in two volumes in 1868 and 1869, Little Women features the March sisters, four young women who remain among the most memorable female characters in American literature. Jo aspires to be a writer, and because Alcott based Jo loosely upon herself, Jo's writing process has the ring of truth to it. So does the illustration, left, from the first edition. Substitute old sweats for Jo's "scribbling suit" and a laptop for her pen, and you have a pretty good idea of how things are going for Loretta and me this month.

"Every few weeks [Jo] would shut herself up in her room, put on her scribbling suit, and 'fall into a vortex', as she expressed it, writing away at her novel with all her heart and soul, for til that was finished she could fine no peace. Her 'scribbling suit' consisted of a black woolen pinafore on which she could wipe her pen at will, and a cap of the same material, adorned with a cheerful red bow, into which she bundled her hair when the decks were cleared for action. This cap was a beacon to the inquiring eyes of her family, who during these periods kept their distance, merely popping in their heads semi-occasionally to ask, with interest, Does genius burn, Jo? They did not always venture even to ask this question, but took an observation of the cap, and judged accordingly. If this expressive article of dress was drawn low upon her forehead, it was a sign that hard work was going on, in exciting moments it was pushed rakishly askew, and when despair seized the author it was plucked wholly off, and cast upon the floor. At such times the intruder silently withdrew, and not until the red bow was seen gaily erect upon the gifted brow, did anyone dare address Jo.

"She did not think herself a genius by any means, but when the writing fit came on, she gave herself up to it with entire abandon, and led a blissful life, unconscious of want, care, or bad weather, while she sat safe and happy in an imaginary world, full of friends almost as real and dear to her as any in the flesh. Sleep forsook her eyes, meals stood untasted, day and night were all too short to enjoy the happiness which blessed her only at such times, and made these hours worth living, even if they bore no other fruit. The divine afflatus usually lasted a week or two, and then she emerged from her 'vortex', hungry, sleepy, cross, or despondent."

Now back into the vortex....

Above: "Jo in a Vortex" from the 1869 first printing of Little Women, Part Second. Louisa May Alcott Collection, Hale Library Special Collections, Kansas State University.

Published on November 30, 2016 21:00

November 28, 2016

Isabel Florence Hapgood

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Not long ago, I posted about the Oread Institute , an early college for women, and promised to write about one of its students.

Isabel Florence Hapgood is one who’s often mentioned in pieces about the Oread Institute. She wasn’t its only famous student, but she’s the one I learned was buried in Worcester. With guidance from William Wallace, Executive Director of the Worcester Historical Museum , my trusty photographer spouse found the grave at the Rural Cemetery , and this photo is the result. It’s a modest marker for a remarkable woman, famous in her day. Because she never married, her body was returned to Worcester, to be buried in the Hapgood family plot in the Rural Cemetery (she's on the left) next to her twin brother, who didn't marry, either.

Isabel Florence Hapgood (1851–1928) attended the Oread Institute from 1863–65, then went on to Miss Porter’s school in Farmington, Connecticut.

She turned out to have a knack for languages—“After graduating, she used her exceptional gift for languages to master in the next ten years most Romance and Germanic languages, and, most importantly, Russian, Polish, and Church Slavonic. She obviously was taken with Russian and…engaged a Russian lady to achieve natural fluency in spoken Russian.”—A Linguistic Bridge to Orthodoxy: Isabel F. Hapgood, by Marina Ledkovsky

In 1885 her first translations from Russian to English appeared. In the years following she translated major works by Tolstoy, Gogol, Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Gorky, Chekhov, and Sonia Kovalesky, among others. She also wrote for the New York Evening Post and the Nation. Her life turns out to be quite exciting: Among other things, she was friends with Leo Tolstoy, invited to visit the Empress Alexandra, and had a narrow escape from Russia when the Revolution began.

In 1885 her first translations from Russian to English appeared. In the years following she translated major works by Tolstoy, Gogol, Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Gorky, Chekhov, and Sonia Kovalesky, among others. She also wrote for the New York Evening Post and the Nation. Her life turns out to be quite exciting: Among other things, she was friends with Leo Tolstoy, invited to visit the Empress Alexandra, and had a narrow escape from Russia when the Revolution began.I would recommend you read at least pp 5-6 of this presentation , to get a sense of her accomplishments and how highly regarded she was.

The History of the Oread Collegiate Institute is a highly detailed account. Among other things it lists faculty and students throughout the school’s history. Ms. Hapgood’s entry is here . She’s in Wikipedia , of course, and the Encyclopedia Britannica . There's a short bio here at Lost Womyn’s Space , and you can see her autograph here .

Cemetery photograph by Walter M. Henritze III. I have been unable to find the original source for the image below, which appears in numerous places.

Published on November 28, 2016 21:30

November 27, 2016

The Tragedy of the Ex Dress & the Settee, c1760-80

Isabella reporting,

Isabella reporting,Fashion never stands still. But as we've discussed here before, women in the past didn't always buy a new dress to reflect a new style, but instead refurbished, retrimmed, or remade existing clothes that they already owned to fit the latest trends. (See examples here , here , here , and here .)

However, that's not what happened to the once-lovely 18thc dress shown here in pieces.

Last week I visited Winterthur Museum for a fine Nerdy History Girls afternoon with Linda Eaton, John & Marjorie P. McGraw Director of Collections and Senior Curator of Textiles. Linda showed me some of the treasures of Winterthur's costume and textiles collection - my idea of a perfect afternoon. In one of the storage rooms, Linda pulled a long archival box from a shelf and asked me if I'd like to see some "ex dresses." This was a new term to me, and at once I envisioned dresses worn by someone's former girlfriend. But in curatorial language, the "ex" refers more to the former state of the textile; in other words, it once was a dress, and now it's a fragment.

When new in 1760-1780, the ex dress shown here was a fashionable robe a la francaise (like this one) , with a floating, pleated back and full petticoat, or skirt. The costly silk was likely woven in either Lyon, France, or Spitalfields, London, England, and imported to colonial America, where it was made up for a wealthy client. The now-unknown mantua-maker who cut and stitched this dress was a skilled seamstress: the meandering floral pattern is carefully matched on the front of the bodice, with the two fronts mirroring one another.

The dress survived intact until the mid-20thc, when it fell prey not to another dressmaker, but to an upholsterer. In a practice common at the time, the dress was cut apart to provide a period-correct fabric for the 18thc settee also in Winterthur's collection, lower right. In theory this was a good choice: the settee was made in New England in 1760-1775, around the same time as the dress, and the style of the robe a la francaise offered plenty of yardage. In the hierarchy of colonial antiques, furniture outranked clothing until the late 20thc (when the study and collecting of historic dress began to be taken more seriously), and so the dress was sacrificed to outfit the settee.

At least the pieces of the dress that couldn't be used were saved - the bodice plus the shaped

sleeve ruffles, upper right, - but while the fragments are useful for study, they're also heartbreaking. To me the final indignity is the the remnants of the linen lining from the back, above left, showing the inner lacing that would have adjusted the now-vanished pleats.

sleeve ruffles, upper right, - but while the fragments are useful for study, they're also heartbreaking. To me the final indignity is the the remnants of the linen lining from the back, above left, showing the inner lacing that would have adjusted the now-vanished pleats.Many thanks again to Linda Eaton for her assistance with this post.

Left: Ex Dress, maker unknown, silk woven in France or England, dress made in North America, 1760-1780, Winterthur Museum.

Lower right: Settee, maker unknown, Massachusetts, 1760-1775, Winterthur Museum.

Photographs used with permission of Winterthur Museum.

Published on November 27, 2016 17:06

November 16, 2016

Thanksgiving Break

As has become our custom, we'll be taking off a week or so from blogging, tweeting, pinning, and all-around social-networking to spend time with family, friends, and a good book or two. Both of us have early-January deadlines (the same day - what are the odds?), so there will probably also be a bit of holiday-writing in the mix.

We each have much to be thankful for - including you, the very best readers, followers, and fellow-nerdy-history-folks in the world.

Have a fantastic holiday,

Loretta & Isabella

Thanksgiving postcard by John Winsch, 1910, New York Public Library.

Published on November 16, 2016 21:00

November 14, 2016

A College for Women is Founded in 1848

Oread Institute 1853

Loretta reports:

Oread Institute 1853

Loretta reports:Once upon a time, in my college days back in the last century, I lived on Castle Street in Worcester. Behind our little street rose a hill*), which we learned was Castle Hill. Queries about the name evoked responses like, "I heard there was a castle on the hill. Or a school or something.” That was about as much as I ever learned, until recently, when a vintage postcard arrived at our house. It showed a castle, and its title, “Oread Institute,” connected in my mind with my old neighborhood, because I recalled s a street by that name not far away.

As my husband I have been learning, Worcester was a happening place in the 1800s and first half of the 1900s.This was why I wasn’t completely surprised when I read here why Worcester was chosen as the site for one of the United States' first higher education institutions for women. It was built by Eli Thayer, and modeled on his alma mater, Brown University. Founded in 1848, it opened 14 May 1849.

History of Oread Institute

History of Oread Institute

Oread Institute in 1870s

Oread Institute in 1870s

As this piece in Gleason’s Pictorial of 19 March 1853 points out, “Here woman enjoys exclusively those privileges which some have regarded as the rightful prerogative of the other sex, having the advantages of a collegiate course of study, if she chooses. And in the attainment of that to which she has long aspired, she is happy.”

Here's a view of Worcester from the Oread Institute in 1858, and here is a detailed study of the college. It

closed in 1881. From 1898 to 1904, it was the Worcester Domestic Science Cooking School.** In 1934 it was demolished.

We’ve located the grave of one of its graduates, about whom I’ll post at a future date.

Image at top: Oread Institute 1853, courtesy Yale University Art Gallery. The photograph below it is described thus: " The Oread Institute, in Worcester, Massachusetts, was an important and popular women's school from 1848 until it closed its doors in 1881. This ca. 1870's photograph is significant not only because it captures the school in its final years, but because it was taken by a woman, Ms. Augustine H. Folsom." Image and quote courtesy American Antiquarian Society , Worcester MA.

*This is the case with most streets in Worcester: level ground is in short supply.

**It's believed that shredded wheat was invented there.

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on November 14, 2016 21:30

November 13, 2016

From the Archives: How (Not) to Dress a 17th c.Puritan Maiden

Isabella reporting,

Isabella reporting,Historical clothing is one of our favorite topics on this blog, and readers of both our posts and books will know how hard we try to get things *right* when in comes to what people were wearing in the past. Yet I'm also willing to concede that there can be considerable wiggle-room when it comes to theatrical costumes (no one really expects Cinderella to wear a perfect replica 18th c. gown, do they?) and other artistic expressions of past fashion.

But what happens when that artist's vision becomes such a potent image that it wipes the real thing clear away?

That was my thought yesterday while reading one of my favorite blogs, historian Donna Seger's Streets of Salem. A recent post featured the 19th c. Anglo-American painter George Henry Boughton (1833-1905), and how his paintings of 17th c. New England Puritans have influenced how we today imagine those early settlers. (Read her post here .) She's right: Boughton's paintings have illustrated countless school history books, and his version of Puritan dress is still widely accepted as the real thing. In fact, when I did a search for the painting, left, the Google best guess that comes up is "Puritan fashion", followed by links to a teaching site that labels this as an example of "colonial clothing."

Except that it isn't. Like most history-painters, Boughton's intentions were the best, but what this young woman is wearing bears no more real resemblance to 17th c. clothing than the sturdy stone walls and substantial brick buildings in the background do to mid-17th c. architecture in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Boughton painted his Puritan maiden in 1875, and to me her expression and posture seem more akin to a fashionable lady of that era; compare her with the lady in James Tissot's Portrait , also painted in 1875.

But it's the costume that Boughton contrived for his model that fascinates me the most. I'm guessing that, like many artists, he had a collection of antique and fancy-dress clothing in his studio, and he assembled an outfit from bits and pieces that looked right to him. To be fair to Boughton, he was trying to create an artistic mood, a somber, thoughtful reverie set in the past, rather than a 17th c. fashion plate. In 1875, people regarded historical clothing as old clothes to be worn to masquerades (no one loved fancy-dress more than the Victorians), and the academic study of dress and fashion was in its infancy.

Still, I'd like to offer a challenge to you. Among our readers, there are many art historians, re-enactors, costume historians, historic seamstresses and tailors, and others of you who know your historical fashion. How many different elements and eras can you see represented in this young woman's costume?

Above: A Puritan Maiden, by George Henry Boughton, 1875, Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute.

Published on November 13, 2016 17:00

November 12, 2016

Breakfast Links: Week of November 7, 2016

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Prize money : frigates, treasure, and Jane Austen.

• The heroines of 19thc cookboooks .

• Kissed against her will : a Victorian case of assault and abuse of power.

• Mesmerizing video via drone of the mist rolling off the cliffs on the Dorset coast.

• Image: Women fishing next to a Studebaker "Big Six" touring car, 1919.

• American child brides and the dangers of underage sex.

• The unique beauty of Dante Gabriel Rosetti.

• Extreme bagpiping situations, from Antarctica to the Beaches of D-Day.

• A metal detectorist finds a 15thc gold ring .

• Sophia Smith's 1818 sampler , made in Connecticut.

• How Emma Hamilton brought ancient Greek fashion to 18thc Europe.

• Image: Gold brooch, c1860-80, depicting a wyvern , a winged two-legged dragon with a barbed tail.

• When Charles Dickens and Edgar Allen Poe met, and Dickens' pet raven inspired Poe's poem.

• Evanion, the Royal Conjurer , plays with fire.

• In 1798, nascent party politics turned George Washington's birthday into a political headache for John Adams.

• The Jersey City devil .

• Image: In praise of doodling! This doodle of a fool was drawn by artist Hans Holbein in the margin of a book in 1515.

• "On being over-fond of animals ", 1765.

• Casket couture? Fashions for the grave, 1915.

• More than just a soundtrack: drums, bugles, and bagpipes in the Seven Years War.

• Was the color green fashionable in the 18thc?

• Image: Just for fun: more proofreader marks .

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection.

Published on November 12, 2016 14:00

November 10, 2016

Friday Video: Recreating an 18thc Agateware Teapot

Isabella reporting,

Recreating an object from the past using the original methods is one of the best ways to understand both the object itself as well as the complexity of the process. It also provides a fresh appreciation for the skill of the original tradespeople, as well as the amount of time (and imagination) that went into making things by hand in the pre-mechanized era.

This novelty agateware teapot from the Victoria & Albert Museum was made in Staffordshire c1750-1765. It was intended to resemble natural agate stone with a swirling effect achieved through layering multicolored clay. The scallop shell shape was created by pressing a thrown base into a mold cast from actual shells, with additional pieces like the spout, handle, and lid made and added separately.

That's the short version of how the teapot was made. This video features Michelle Erickson, who was Ceramic Resident: World Class Maker at the V&A in 2012, recreating a replica of the original teapot, and showing exactly how labor-intensive that 18thc process was.

Above: Teapot, maker unknown, c1750-1765, Victoria & Albert Museum.

If you received this post via email, you may be seeing a black box or empty space where the video should be. Click here to view the video.

Published on November 10, 2016 21:00