Walter Coffey's Blog, page 184

August 19, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Aug 19-25, 1863

Wednesday, August 19

In New York City, the Federal military draft resumed without incident; troops guarded the draft offices to prevent the violence that had occurred in July. In Charleston Harbor, Federal cannon blasted Confederate positions at Fort Sumter and Battery Wagner for a third day. In Florida, a Confederate signal station was captured at St. John’s Mill, and skirmishing occurred in West Virginia and Tennessee.

Thursday, August 20

Colonel Christopher “Kit” Carson’s Federals left Pueblo, Colorado to stop depredations against settlers by Navajo Indians in the New Mexico Territory. The Federal objective was to move the Indians to a reservation at Bosque Redondo on the Pecos near Fort Sumner.

In Tennessee, General William S. Rosecrans’s Federal Army of the Cumberland approached the Tennessee River during their advance on Chattanooga. In addition, Federal troops were transferred from Kentucky to aid in the Federal offensive in eastern Tennessee.

In Charleston Harbor, Federal guns continued pummeling Fort Sumter and Battery Wagner. In Kansas, William C. Quantrill and about 450 Confederate raiders approached Lawrence. A Federal expedition began from Vicksburg, Mississippi to Monroe, Louisiana.

Friday, August 21

William C. Quantrill’s Confederate raiders rampaged through Lawrence, Kansas. Quantrill’s men robbed the bank, killed 180 men, burned 185 buildings, and cost about $1.5 million in property damage. Quantrill’s main target–Republican Senator James Lane–escaped into a cornfield in his nightshirt. The attack was the result of bitterness from the Kansas border war, a prior Federal raid on Osceola, and Quantrill’s dislike of the anti-slavery town. An eyewitness said, “The town is a complete ruin. The whole of the business part, and all good private residences are burned down. Everything of value was taken along by the fiends… I cannot describe the horrors.”

Federal General Q.A. Gillmore threatened to bombard Charleston if Fort Sumter was not surrendered and Morris Island was not evacuated. The Confederates refused, and the Federal bombardment resumed. However, casualties remained low. A Confederate torpedo boat attempted to destroy a Federal ship, but its detonation device failed and it retreated under heavy fire.

Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee and Alabama as part of William Rosecrans’s Federal advance on Chattanooga. Skirmishing also occurred in West Virginia.

Saturday, August 22

Fort Sumter was attacked by five naval vessels. Although there were few remaining guns to return fire, the Confederate defenders refused to surrender. Federal guns began firing on Charleston, but the famed Swamp Angel exploded while firing a round.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis worked to get reinforcements for General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee defending Chattanooga. In Kansas, skirmishing occurred as Quantrill’s Confederates left Lawrence in ruins. Skirmishing occurred in West Virginia, Tennessee, and the Arizona Territory.

Sunday, August 23

The Federal bombardment of Fort Sumter temporarily ended after nearly 6,000 rounds had been fired into the fort, leaving it in ruins. In Virginia, Confederates captured two Federal gunboats at the mouth of the Rappahannock River, which caused irritation in the North. Skirmishing occurred in Arkansas, and Federals scouted Bennett’s Bayou, Missouri.

Monday, August 24

In Virginia, John Singleton Mosby’s Confederate raiders began harassing Federals belonging to General George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac. Federal scouting also occurred at various points in Virginia.

The Federal bombardment of Fort Sumter and Battery Wagner decreased. Skirmishing occurred in Alabama.

Tuesday, August 25

Responding to the Lawrence massacre and citizens aiding the Confederate raiders, Federal General Thomas Ewing, Jr., commanding from Kansas City, issued General Order No. 11. This compelled residents of four Missouri counties to abandon their homes and seek refuge at military posts if they could prove their loyalty to the Union. This forcibly relocated at least 20,000 people around Kansas City. As the residents left, pro-Union “Jayhawkers” looted their homes. Ewing’s order actually encouraged more Confederate guerrilla attacks by enraging local citizens against his Federal relocation policy.

In Charleston Harbor, Federal forces failed to capture Confederate rifle pits in front of Battery Wagner. In Virginia, Confederates captured three Federal schooners at the mouth of the Rappahannock River. In West Virginia, Federals destroyed Confederate saltpeter works on Jackson’s River. Skirmishing occurred in Missouri and Arkansas.

Primary Source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

August 14, 2013

The Contentious Election of 1824

John Quincy Adams was elected president without winning either the electoral or popular vote. The resentment caused by this disputed victory led to the birth of the Democratic Party.

6th U.S. President John Quincy Adams

The 1824 contest pitted four candidates against each other: Adams of Massachusetts, Henry Clay of Kentucky, William Crawford of Georgia, and Andrew Jackson of Tennessee.

Adams was secretary of state under President James Monroe. He had been favored to win primarily because those serving as secretary of state usually succeeded the outgoing president. As the son of former President John Adams, John Quincy had a famous family name and extensive foreign policy experience. But his anti-slavery views made him unpopular in the South, and his perceived elitist demeanor made him unpopular in the North.

Speaker of the House Henry Clay was known for his efforts to secure the Missouri Compromise between North and South in 1820. Clay was an influential politician who championed the “American System,” a program advocating more government intervention in the economy. He also claimed to oppose slavery, even though he owned slaves.

William Crawford was a prominent southern politician who was endorsed by Presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe. But since he was a strong supporter of slavery, he alienated northern voters. In addition, Crawford had suffered a stroke during the presidential campaign and was nearly paralyzed, which hurt his chances for victory.

Former General Andrew Jackson was a slavery advocate from Tennessee, and his status as a war hero of the War of 1812 and the Seminole War appealed to both northerners and southerners. Jackson was also viewed as a “man of the people,” and a man who could continue the legacy begun by George Washington in which top military leaders become president. He avoided committing to key issues and ignored the slavery issue during the campaign.

Each candidate was popular in a different region. Adams and Clay were strongest in the Northeast and Northwest respectively, and Crawford and Jackson were most popular in the Southeast and Southwest. From a political perspective, Adams and Clay were more similar in ideology than Crawford and Jackson. In addition, Clay personally detested Jackson because he felt that Jackson’s credentials as a military commander did not merit him becoming the president.

Character trumped issues in this campaign. Adams was ridiculed for his cold manner, Clay was accused of being a drunk, Crawford was accused of misconduct, and Jackson was accused of murder for ordering the execution of alleged Indian sympathizers during the Seminole War. Many states allowed men who owned no property to vote for the first time, which held the potential for a large voter turnout.

When the results were tallied, Jackson received 99 electoral votes, more than any other candidate. He also won more popular votes than Adams and Clay combined. Adams finished second with 84, Crawford finished third with 41, and Clay finished fourth with 37. Even though Jackson finished first, he fell short of the 51 percent of the electoral votes needed for victory, so he could not be declared the winner. Instead, the House of Representatives was required to decide the contest.

Under the Twelfth Amendment, only the top three vote-getters could be considered, so Clay was eliminated. But as House speaker, Clay had enormous influence over who would win the election. Crawford’s stroke and his polarizing support of slavery left him out, leaving Jackson and Adams. Since Clay despised Jackson, and since Clay was more politically similar to Adams, the House elected Adams president on the first ballot. Clay cast the final ballot to award the election to Adams.

Jackson’s supporters were shocked and dismayed by Adams’s quick victory. They protested that the will of the people had been ignored. However, this was not entirely true because only four states had all four candidates on the ballot. Also, none of the candidates could truly represent the true will of the people because women and blacks–a large portion of the people–were barred from voting.

The Jacksonian protests turned into outrage when Adams named Clay to be his secretary of state. Since secretaries of state had traditionally succeeded outgoing presidents, this meant that Clay could have been next in line for the presidency. Consequently, many Jackson backers accused Adams and Clay of making a “corrupt bargain” to rob Jackson of the White House.

Both Adams and Clay denied the charges, and no evidence suggests that a deal had been struck before Adams was elected. But the fact that Adams won the presidency without winning either the popular or electoral vote, and the fact that Clay was appointed to Adams’s top cabinet post left many bitter and eager for revenge four years later.

Adams had enjoyed only moderate popularity before becoming president, and his perceived alliance with Clay to defeat Jackson doomed him to an ineffective term. His presidency was constantly challenged by a coalition devoted to defeating him in the next election.

This began the modern two-party system in American politics, as Adams’s supporters became known as the National Republicans, and Jackson’s supporters formed the Democratic Party, one of the first national political parties in the U.S. The Democrats finally elected Jackson president four years later.

August 12, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Aug 12-18, 1863

Wednesday, August 12

On the South Carolina coast, Federal cannon began firing on Confederate positions at Fort Sumter and Battery Wagner in Charleston Harbor. This was an effort to test the range of the heavy Parrott rifles, but it began a new Federal offensive against the harbor. Fort Sumter was severely damaged by the batteries.

President Abraham Lincoln refused to grant an army command to General John McClernand, who had been relieved as corps commander by General Ulysses S. Grant for insubordination. A Federal expedition began from Memphis, Tennessee to Grenada, Mississippi. Skirmishing occurred in Mississippi.

Thursday, August 13

A Confederate army chaplain wrote to President Jefferson Davis “that every disaster that has befallen us in the West has grown out of the fact that weak and inefficient men have been kept in power… I beseech of you to relieve us of these drones and pigmies.” The recent Confederate defeats had caused dissension among the ranks, especially in the Western Theater. The chaplain cited General John C. Pemberton, who had surrendered at Vicksburg in July, and General Theophilus H. Holmes, commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department.

Federals continued their practice fire on Fort Sumter and Battery Wagner from land batteries and naval guns. In Arkansas, a Federal expedition began up the White and Little Red Rivers. Federals also began an expedition against Indians in the Dakota Territory. Skirmishing occurred in Mississippi and Missouri.

Friday, August 14

Federals continued their practice fire in Charleston Harbor. General George G. Meade, commander of the Federal Army of the Potomac, met with President Lincoln and his cabinet to provide details of the Gettysburg Campaign. In Virginia, Federal expeditions began near Winchester and the Bull Run Mountains. Skirmishing occurred in North Carolina, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Saturday, August 15

In Virginia, a Federal expedition against Confederate partisans began from Centreville. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia and Arkansas.

Sunday, August 16

In Tennessee, General William S. Rosecrans’s Federal Army of the Cumberland began advancing on Chattanooga. Since Rosecrans had captured Tullahoma in July, the Lincoln administration had repeatedly urged him to continue his advance. Rosecrans had initially hesitated because his flanks were threatened by Confederates in Mississippi and eastern Tennessee. However, Ulysses S. Grant’s Federals now opposed the Confederates in Mississippi, and Ambrose Burnside’s Federals opposed Confederates in eastern Tennessee.

Rosecrans planned to cross the Tennessee River south and west of Chattanooga, hoping to trap General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee between his forces and Burnside’s. Meanwhile, Bragg desperately pleaded for President Davis to send him reinforcements. Confederate scouts informed Bragg that Rosecrans was advancing from the southwest at Stevenson, while Burnside began moving on Knoxville. Bragg remained entrenched at Chattanooga, unsure of which force to fight.

Federals continued practice firing on Confederate targets in Charleston Harbor. Work crews hurried to repair damages to Fort Sumter and Battery Wagner before Federal artillery damaged them again.

President Lincoln wrote to New York Governor Horatio Seymour regarding the military draft: “My purpose is to be just and fair; and yet to not lose time.” A Federal expedition began from Memphis, Tennessee to Hernando, Mississippi. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia and Mississippi.

Monday, August 17

On the South Carolina coast, Federal artillery opened in earnest against Fort Sumter and Batteries Wagner and Gregg. The 11 cannon on Morris Island included the 200-pound “Swamp Angel,” and were joined by naval guns in firing 938 shots that crumbled Sumter’s walls. But the rubble formed an even stronger defense against Federal fire.

Federal expeditions began from Cape Girardeau and Pilot Knob, Missouri to Pocahontas, Arkansas. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee and Arkansas.

Tuesday, August 18

Federals continued their heavy bombardment of Fort Sumter and Batteries Wagner and Gregg. Confederate positions were severely damaged, but the troops refused to surrender.

In Washington, President Lincoln tested the new Spencer repeating rifle at Treasury Park. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, North Carolina, and Kentucky. Federals clashed with Indians in the New Mexico Territory.

Primary source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

August 9, 2013

The Teapot Dome Scandal

Teapot Dome was one of the most notorious political scandals of the early 20th century, and one of many scandals in the administration of President Warren Harding.

Teapot Dome was a region of oil-rich land in Wyoming. In 1909, a presidential order set aside this land, along with oil-rich lands in Elk Hills and Buena Vista, California, for potential use by the U.S. Navy. Meanwhile, private companies refined oil near each of these three regions, and federal officials became concerned that these companies may start siphoning oil from the government lands.

Teapot Dome was a region of oil-rich land in Wyoming. In 1909, a presidential order set aside this land, along with oil-rich lands in Elk Hills and Buena Vista, California, for potential use by the U.S. Navy. Meanwhile, private companies refined oil near each of these three regions, and federal officials became concerned that these companies may start siphoning oil from the government lands.

As a result, in 1920 Congress authorized the Navy secretary to administer the lands in Teapot Dome, Elk Hills and Buena Vista as he saw fit. There were two viable options: 1) Drill offset wells on the land boundaries to minimize siphoning, or 2) Lease the land to the companies for drilling if they promised to set aside sufficient oil for the Navy in case of emergency. The Navy secretary chose the first option.

In 1921, President Woodrow Wilson was succeeded by Warren Harding, and newly appointed Interior Secretary Albert B. Fall persuaded President Harding that the second option would be better. Naval officials feared oil shortages in case of conflict with foreign nations, particularly Japan. Fall assured them that the money collected for the leases would be used to construct new oil depots at strategic defensive points such as Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

To put his plan in motion, Fall convinced Harding to transfer authority over the lands from the Navy Department to Fall’s Interior Department. Thus, Fall was now in charge of the oil reserves. He quickly leased the land at Teapot Dome to Harry F. Sinclair, owner of Mammoth Oil, and the land at Elk Hills to Edward L. Doheny, owner of Pan-American Oil. Both oil reserves were leased without competitive bidding.

On April 14, 1922, the Wall Street Journal revealed the arrangement between Fall and Sinclair for Teapot Dome. The next day, Democratic Senator John B. Kendrick of Wyoming called on Fall to explain why he had leased the fields to Sinclair without competitive bidding. Fall explained that this was because Teapot Dome belonged to the military, and competitive bidding would have generated publicity that could threaten national security. Upon Senate investigation, it was determined that the deals were legal under the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920. The story faded, but the Senate continued digging.

Republican Senator Robert M. LaFollette of Wisconsin, chairman of the Senate Committee on Public Lands, assigned the committee’s most junior minority member, Democratic Senator Thomas J. Walsh of Montana, to investigate the matter. Since it was already determined that the deals were legal, the question became how Fall got so rich so quickly because his living standards suddenly and noticeably improved.

As the investigations escalated, Fall finally resigned under pressure in March 1923. Later that year, a Senate subcommittee chaired by Walsh convened to formally investigate. It was discovered that in November 1921, prior to leasing the lands, Fall had been loaned $100,000 interest-free by Doheny. It was also discovered that shortly after Fall resigned, he accepted $260,000 in bonds from Sinclair. Altogether Fall had accepted gifts or loans totaling $404,000 from oil executives. These revelations exposed what became known as the Teapot Dome scandal.

Since leasing the oil fields was legal, Fall was indicted for bribery, not for the leases. In 1924, Fall was convicted of accepting bribes, sentenced to one year in prison, and fined $100,000. This made him the first presidential cabinet member to ever be convicted of crimes committed while in office.

Since leasing the oil fields was legal, Fall was indicted for bribery, not for the leases. In 1924, Fall was convicted of accepting bribes, sentenced to one year in prison, and fined $100,000. This made him the first presidential cabinet member to ever be convicted of crimes committed while in office.

In separate bribery trials, Doheny and Sinclair were acquitted of bribing Fall. However, Sinclair was convicted on a count of contempt of the Senate for refusing to answer questions, and jury tampering for hiring detectives to investigate jurors. He served a short prison sentence and was fined $100,000. The Supreme Court ultimately ruled that the oil fields were leased through “corrupt” means. The leases were invalidated, and the land was returned to government control.

While Teapot Dome was a major scandal, it was by no means the only scandal that plagued the Harding administration. Separate incidents included:

Thomas W. Miller, head of the Office of Alien Property, was convicted of accepting bribes

Jess Smith, personal aide to the attorney general, committed suicide after destroying papers

Charles Forbes, Director of the Veterans Bureau, was convicted of fraud and bribery for skimming profits, taking kickbacks and running an illegal alcohol and drug ring

Charles Cramer, aide to Forbes, committed suicide

Although President Harding was not directly linked to any of these scandals (and he died before most of the corruption came to light), Teapot Dome was the prime indication that he was either unwilling or unable to stop the corruption in his administration. President Calvin Coolidge, who succeeded Harding upon his death, blamed the scandal on congressional Republicans and was elected to his own term in 1924 under the slogan, “Keep Cool With Coolidge.”

One lasting legacy of the Teapot Dome scandal came when it was revealed that the Bureau of Investigation had illegally monitored and wiretapped the offices of congressmen investigating the scandal. This revelation prompted Bureau reform, leading to the creation of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the appointment of J. Edgar Hoover as its first director.

August 5, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Aug 5-11, 1863

Wednesday, August 5

President Lincoln wrote to General Nathaniel Banks, commander of the Federal Department of the Gulf: “For my own part I think I shall not, in any event, retract the emancipation proclamation; nor, as executive, ever return to slavery any person who is free by the terms of that proclamation, or by any of the acts of Congress.”

In Arkansas, General Frederick Steele assumed command of Federal troops at Helena. On the South Carolina coast, Confederates strengthened defenses at Fort Sumter and Battery Wagner in Charleston Harbor. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, West Virginia, and Mississippi.

Thursday, August 6

In accordance with President Lincoln’s proclamation, the northern states observed a day of thanksgiving for the recent Federal victories. Confederate President Jefferson Davis wrote to South Carolina Governor M.L. Bonham pledging relief for Charleston, “which we pray will never be polluted by the footsteps of a lustful, relentless, inhuman foe.”

C.S.S. Alabama captured Sea Bride amidst cheers off the Cape of Good Hope. In Virginia, John S. Mosby’s Confederate raiders captured a Federal wagon train near Fairfax Court House. Skirmishing occurred in West Virginia.

Friday, August 7

President Lincoln refused New York Governor Horatio Seymour’s request to suspend the military draft, explaining, “My purpose is to be, in my action, just and constitutional; and yet practical, in performing the important duty, with which I am charged, of maintaining the unity, and the free principles of our common country.” Skirmishing occurred in Virginia and Missouri.

Saturday, August 8

General Robert E. Lee submitted his resignation as commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia to President Davis. Lee was in poor health, and he blamed himself for the defeat at Gettysburg in July. Lee wrote, “I, therefore, in all sincerity, request your excellency to take measures to supply my place.”

On the South Carolina coast, Federals continued building approaches to Battery Wagner, using calcium lights to work at night. Off the Florida coast, U.S.S. Sagamore seized four prizes. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Mississippi, and Missouri.

Sunday, August 9

In a letter to General Ulysses S. Grant at Vicksburg, President Lincoln wrote that black troops were “a resource which, if vigorously applied now, will soon close the contest.” Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Tennessee, and Missouri.

Monday, August 10

In Arkansas, Frederick Steele’s Federals began advancing on Little Rock from Helena. Thirteenth Corps was transferred from Ulysses S. Grant’s army at Vicksburg to Carrollton, Louisiana. In Texas, Confederate regiments mutinied at Galveston due to lack of rations and furloughs, but order was quickly restored.

President Lincoln wrote to General William S. Rosecrans, commanding the Federal Army of the Cumberland in Tennessee, “I have not abated in my kind feeling for and confidence in you… Since Grant has been entirely relieved by the fall of Vicksburg, by which (Confederate General Joseph E.) Johnston (in Mississippi) is also relieved, it has seemed to me that your chance for a stroke, has been considerably diminished…” Skirmishing occurred in Louisiana and Missouri.

Tuesday, August 11

On the South Carolina coast, Confederate artillery at Battery Wagner, Fort Sumter, and James Island pounded entrenched Federals. In Virginia, Confederates captured a Federal wagon train near Annandale.

After pondering Robert E. Lee’s resignation, President Davis refused, stating, “our country could not bear to lose you.” A pro-Union meeting voiced support for the Federal war effort at Washington, North Carolina.

Primary Source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

August 2, 2013

The Infamous Dred Scott Ruling

In 1857, the Supreme Court rendered one of the most controversial and repugnant decisions in American history by ruling that slaves were property, not human beings.

Dred Scott

Dred Scott was a Missouri slave whose master was a U.S. army surgeon. The army transferred the surgeon to various states and territories, and he brought Scott with him. They briefly lived in the Wisconsin Territory (present-day Minnesota), where slavery was prohibited.

When the surgeon died, Scott and his family were ultimately inherited by John F.A. Sanford of New York. Scott sued Sanford for his freedom, arguing that he was entitled to freedom because he had briefly lived where slavery was prohibited according to the Missouri Compromise of 1820. That compromise had banned slavery north of Missouri, which included the Wisconsin Territory.

The case finally reached the Supreme Court in 1857, after 11 years of trials and appeals. James Buchanan became the 15th U.S. president in March of that year. In his inaugural address, Buchanan declared that the Dred Scott case and the issue of slavery ”belongs to the Supreme Court of the United States, before whom it is now pending, and will, it is understood, be speedily and finally settled.” Two days after Buchanan’s inauguration, the Court ruled 7 to 2 in Scott v. Sandford (Sanford’s name was misspelled) that Dred Scott was not entitled to freedom.

Writing the majority opinion, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney ruled that blacks were historically “so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Thus, blacks could not be U.S. citizens, regardless of whether they were free or enslaved. To validate this point, Taney cited numerous laws limiting or prohibiting citizenship for blacks, especially in the northern states. Only states could confer citizenship on persons, not the Court.

This meant that Dred Scott could not be a U.S. citizen because he was black. Since Scott could not be a U.S. citizen, he had no right to sue in a federal court. Thus, the Supreme Court had no authority to hear such a case, and the lower court rulings that Scott was not entitled to freedom were upheld. But Taney exceeded the case’s scope by establishing two more controversial points:

First, Scott had no right to sue under the terms of the Missouri Compromise because that law was unconstitutional. This despite the fact that the validity of the law was not questioned in this case.

Second, the federal government could not confiscate slaves from their masters, even if they moved to free states, because it violated the Fifth Amendment banning federal seizure of private property without due process of law.

Thus, slaves were considered property, not persons, and the federal government could not stop citizens from bringing their property into any state or territory. This opened the path toward expanding slavery throughout the country.

The two dissenting justices issued objections to Taney’s ruling:

First, they argued that Taney should have not rendered the second part of his ruling, instead simply ending the case by ruling that it was outside the Court’s jurisdiction since Scott was not considered a citizen.

Second, they noted that the Missouri Compromise was valid because it was based on the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which had prohibited slavery in the region around the Great Lakes, and was endorsed by most of the nation’s founders.

Third, they asserted that there was no legal basis to deny citizenship to blacks because when the Constitution was ratified, 10 of the 13 original states had allowed black suffrage. Even though black civil and voting rights had been largely curtailed since then, past recognition of black citizenship could not now be revoked.

Evidence suggests that James Buchanan helped influence the decision before becoming president in an effort to resolve the slavery issue once and for all. Buchanan had written to Justice John Catron asking his help in deciding the case before Buchanan’s inauguration. Buchanan also persuaded fellow Pennsylvanian Robert C. Grier to side with Taney to show northern support for the decision and make the verdict appear more decisive.

Ruling the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional marked just the second time that the Supreme Court had invalidated an act of Congress (the first was Marbury v. Madison in 1803). Even so, the ruling had little effect since the compromise had been effectively ended by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Nevertheless, the decision sparked outrage among liberty advocates due to its callous definition of fellow human beings as property.

This ruling was cheered in the South and condemned in the North, thus further dividing the country. Northern antislavery advocates were horrified that slaveholders could now expand slavery throughout the new western territories, or even into the northern states. The Albany Evening Journal called the decision a victory for slavery which was an offense to the founding principle of individual freedom.

Politically, northerners feared that this could expand southern political influence in Washington and shift the balance of federal power to the South. Southern congressmen soon introduced bills to extend slavery into the territories and even to revive the African slave trade. The Democratic Party split over the ruling along North-South lines. The ruling also invalidated the Republican Party’s platform, which favored banning slavery in the western territories. This emboldened more northerners to side with the abolitionists and support the Republicans in the 1860 elections.

Financial backers purchased the freedom of Dred Scott and his family before Scott died the year after the ruling. Roger B. Taney’s reputation as a justice was irreparably harmed by this case. Also irreparably harmed was sectional harmony, as the ruling only split North and South apart even further. The decision was eventually overturned by the post-war Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, which ended slavery and conferred national citizenship on all persons born in the U.S.

July 29, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Jul 29-Aug 4, 1863

Wednesday, July 29

Following the string of Confederate defeats this month, Queen Victoria of England informed the British Parliament that she saw “no reason to depart from the strict neutrality which Her Majesty has observed from the beginning of the contest.”

President Abraham Lincoln stated that he opposed “pressing” General George G. Meade, commanding the Federal Army of the Potomac, into immediately attacking General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Skirmishing occurred in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Alabama. Federals clashed with Indians in the Dakota and New Mexico territories.

Thursday, July 30

President Lincoln directed General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck to issue an order declaring the U.S. government would “give the same protection to all its soldiers, and if the enemy shall sell or enslave anyone because of his color, the offense shall be punished by retaliation upon the enemy’s prisoners in our possession…” This “Order of Retaliation” was prompted by the Confederate order “dooming to death or slavery every negro taken in arms, and every white officer who commands negro troops.”

Lincoln’s order sought to offset the Confederacy’s “relapse into barbarism,” stating “the law of nations and the usages and customs of war as carried on by civilized powers, permit no distinction as to color in the treatment of prisoners of war.” Under this order, “for every soldier of the United States killed in violation of the laws of war, a rebel soldier shall be executed; and for every one enslaved by the enemy or sold into slavery, a rebel soldier shall be placed at hard labor.”

Skirmishing occurred in South Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Friday, July 31

In Virginia, Federals clashed with Confederates while crossing the Rappahannock River at Kelly’s Ford. Skirmishing occurred in West Virginia, Kentucky, and Mississippi.

Saturday, August 1

Federal Rear Admiral David D. Porter assumed command of naval forces on the Mississippi River. Now that the entire waterway was in Federal hands, Porter’s main objective was to defend against Confederate guerrilla attacks on Federal shipping.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis offered amnesty to all soldiers absent without leave if they would return to their units within 20 days. In asking for more sacrifice, Davis proclaimed that “no alternative is left you but victory, or subjugation, slavery and utter ruin of yourselves, your families and your country.”

In Virginia, a cavalry skirmish near Brandy Station ended the Gettysburg Campaign. On the South Carolina coast, Federals began concentrating for another attack on Battery Wagner in Charleston Harbor. The Federal War Department disbanded the Fourth and Seventh Army Corps.

Prominent Confederate spy Belle Boyd was imprisoned in Washington a second time after being apprehended in Martinsburg, West Virginia. Skirmishing occurred in Kentucky, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Sunday, August 2

On the South Carolina coast, Federals attacked the Confederate steamer Chesterfield off Morris Island in Charleston Harbor. President Davis wrote Robert E. Lee, ”It is painful to contemplate our weakness when you ask for reinforcements.” Skirmishing occurred in Virginia.

Monday, August 3

In response to the New York City draft riots last month, New York Governor Horatio Seymour requested that President Lincoln suspend the military draft in his state. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

Tuesday, August 4

On the South Carolina coast, Federals continued bombarding Charleston Harbor while preparing the “Swamp Angel,” a massive cannon, to aid in the bombardment. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, West Virginia, and Tennessee.

Primary Source: The Civil War Day-by-Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

July 28, 2013

Liberty Threatened by the Alien and Sedition Acts

Less than 10 years after the founding of the American republic, a series of federal laws threatened the freedoms supposedly guaranteed by the new U.S. Constitution.

In 1798, the new United States experienced tense diplomatic relations with Great Britain and France because those countries were seizing U.S. ships on the high seas. This was splitting federal politicians into two factions called the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans (i.e., Republicans).

In 1798, the new United States experienced tense diplomatic relations with Great Britain and France because those countries were seizing U.S. ships on the high seas. This was splitting federal politicians into two factions called the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans (i.e., Republicans).

The Federalists favored closer relations with the British, a strong federal government, and a loose interpretation of the Constitution. The Republicans favored closer relations with the French, a limited federal government, and a strict interpretation of the Constitution. The Federalists controlled both houses of Congress, and Federalist John Adams was president.

When U.S. diplomats attempted to negotiate a peace with France, French agents refused to talk unless a bribe was paid first. This prompted congressional Federalists to call for war against France. The Federalists also feared that pro-French citizens and immigrants, primarily Republicans, would undermine a potential war by favoring France over their own country.

As a result, the Federalist majority passed a series of laws in the summer of 1798 that became known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. These were intended to tighten immigration restrictions, limit critical speech against the government, and curtail “anti-American” (i.e., Republican) criticism in the press. The Alien and Sedition Acts consisted of four measures:

The Naturalization Act lengthened the requirement for foreigners to receive citizenship from five to 14 years. This was primarily aimed at French and Irish immigrants, most of whom were Catholics and/or Republicans.

The Alien Act and Alien Enemies Act authorized the president to order the arrest and/or deportation of aliens “dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States” during peacetime and wartime respectively. Vice President Thomas Jefferson, a leading Republican, believed that these laws targeted his political ally, Albert Gallatin, because he was born in Geneva.

The Sedition Act prohibited the criticism of government officials “with intent to defame… or bring into contempt or disrepute,” and punished anyone who would “print, utter, or publish… false, scandalous and malicious writing” about the president or Congress. This was mostly aimed at critical Republican newspapers.

Federalists argued that these laws were needed to stop disloyalty and give President Adams redress against defamation. They also cited the recent Reign of Terror in France and expressed fear that government criticism would spark a similar bloody rebellion in the U.S.

Republicans not only opposed the acts, but they were outraged by the way the laws were enforced. Over two dozen men were arrested, most of whom were Republican newspaper editors who were jailed and their papers suppressed. Benjamin Franklin Bache, grandson of Benjamin Franklin and editor of the Philadelphia Democrat-Republican Aurora, was arrested for allegedly libeling President Adams. A man was fined $100 for saying he hoped that the presidential cannon would “hit Adams in the ass.”

Other Republicans were harassed and threatened with arrest. Federalist judges used the loosely worded laws to trump up charges and imprison political dissenters. Republican Congressman Matthew Lyon denounced these acts and spat in the eye of a Connecticut Federalist. He was jailed and won reelection while imprisoned. The Alien and Sedition Acts proved to be the first crisis concerning the viability of the constitutional guarantees of free speech, press, association, assembly, and expression.

In addition to charges of unfair enforcement, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison argued that the Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional in their Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. The resolutions cited the Tenth Amendment, under which powers not delegated to the federal government belong to either the states or the people. Thus the acts, by violating the First Amendment, violated the Tenth Amendment as well and should be considered null and void.

Jefferson and Madison further declared that the laws infringed on state sovereignty, which violated the compact between the states and the federal government. Under this “compact theory,” states have the right to nullify federal laws deemed unconstitutional because the states had created the federal government and voluntarily agreed to form a compact for their mutual benefit that became known as the United States.

This was the first doctrine of states’ rights, and it introduced the principle of nullification that would be invoked to challenge federal authority in the future.

Like most federal legislation, the Alien and Sedition Acts produced unintended consequences. First, the laws proved so unpopular that they led to sweeping Republican victories in the 1800 elections, including the election of Thomas Jefferson as president. The acts were allowed to expire after Jefferson took office.

Second, the Federalists never fully recovered from Jefferson’s victory in 1800 and the faction eventually dissolved, only to be resurrected as the Whig Party in the 1830s, and again as the Republican Party in the 1850s.

Third and perhaps most importantly, the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions introduced the concepts of state sovereignty and nullification that would become the primary political issues of the 19th century, ultimately leading to the southern secession and war.

July 25, 2013

National Supremacy Under McCulloch v. Maryland

In 1819, the Supreme Court set a landmark precedent by ruling that the federal government is supreme over the individual states, even though there is no such distinction in the Constitution.

The case involved the Second Bank of the United States, a national bank that had been chartered by Congress in 1816. When the Bank opened branches in the states, it adversely affected the business of state and local banks already operating. To remedy this, Maryland passed a law “to impose a tax on all banks, or branches thereof, in the State of Maryland, not chartered by the legislature.”

The annual tax on Bank branches in Maryland was $15,000. It was intended to drive the Bank out of the state because the Bank mainly served the interests of the federal government, which were not necessarily compatible with the state’s interests.

James W. McCulloch, cashier of the Bank’s Baltimore branch, was sued by the state of Maryland when he refused to pay the annual tax. The Maryland Court of Appeals decided in favor of the state, asserting that “the Constitution is silent on the subject of banks,” which meant that Congress had no authority to charter a national bank. McCulloch appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

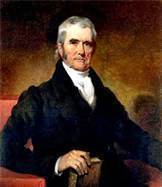

U.S. Chief Justice John Marshall

In a unanimous ruling, the Court overturned the appeals court decision by finding for McCulloch. Chief Justice John Marshall wrote the Court’s opinion, which addressed two key issues: whether the Bank was unconstitutional, and whether states could tax federal entities.

On the first point, Marshall wrote that Congress has the power to “incorporate the subscribers to the Bank of the United States,” which meant that the Bank was a constitutional entity.

Acknowledging that there is no specific language in the Constitution allowing Congress to create a national bank, Marshall invoked the same argument used by Alexander Hamilton to justify creating the first Bank of the United States in 1791. Marshall contended that the federal government had certain “implied powers,” referring to Article I, Section 8 which stated that Congress could “make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers” listed in the same section.

Marshall stated, “There is nothing in the Constitution… which exclude incidental or implied powers. If the end be legitimate… all the means which are appropriate… may constitutionally be employed to carry it into effect.” Thus, Marshall essentially declared that Congress could pass unconstitutional laws (i.e., chartering a national bank) as a means to an end, as long as that end remains within the constitutional scope (i.e., enhancing congressional power to tax, coin money, etc.).

On the second point, Marshall wrote that the “Government of the Union, though limited in its powers, is supreme within its sphere of action, and its laws, when made in pursuance of the Constitution, form the supreme law of the land.” This prohibited Maryland from taxing the Bank because the Bank had been created by federal law which, in the Court’s opinion, was supreme over state law.

This so-called “supremacy clause” meant that “States have no power, by taxation or otherwise, to retard, impede, burthen, or in any manner control the operations of the constitutional laws enacted by Congress to carry into effect the powers vested in the national Government.” There is no mention of a “supremacy clause” in the Constitution, and the result of such a notion has tipped the balance of power decidedly toward the national government in the federalist system.

In declaring all state laws that conflict with federal law null and void, Marshall warned the states that “the power to tax involves the power to destroy.” However, this ruling simply replaced the power of states to tax with the federal power to tax, which now has more power to destroy than any state ever had.

Marshall was a prominent ally of Alexander Hamilton and other Federalists who favored more federal power at the states’ expense. This ruling reflected the general trend in which federal power trumped state powers in cases decided by the federal judiciary.

The ruling was largely ignored at the time. This was mainly because Americans of the early 19th century were more connected with the Constitution’s original intent, which saw the federal judiciary more as an advisory body that would issue opinions with no authority to actually enforce or overturn law. But as time went on, the federal government gradually began asserting its authority over the states, and when the southern secession was defeated in the Civil War, the states were made permanently subservient to federal authority.

McCulloch v. Maryland was one of the first steps on the march toward centralization. This ruling set the precedent for future Congresses to enact constitutionally questionable legislation simply because it is arbitrarily deemed “necessary and proper.” Rulings such as these are largely responsible for the overreaching, over-intrusive federal government that exists today.

July 22, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Jul 22-28, 1863

Wednesday, July 22

In Ohio, General John Hunt Morgan’s Confederate raid continued with skirmishing at Eagleport. Morgan’s Confederates fled northward from Federal pursuers.

In Virginia, General George G. Meade, commanding the Federal Army of the Potomac, directed General William H. French, commanding Third Corps, to attack Confederates under General Robert E. Lee in Manassas Gap tomorrow. The New York Chamber of Commerce estimated that Confederate raiders had taken 150 Federal merchant vessels valued at over $12 million. Skirmishing occurred in North Carolina and Louisiana.

Thursday, July 23

In Virginia, William H. French’s Federals pushed through Manassas Gap but were delayed for hours by a Confederate brigade. This allowed the remainder of Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia to escape southward. Other skirmishing occurred at various points, but George G. Meade’s effort to destroy Lee in the Shenandoah Valley failed.

In Ohio, John Hunt Morgan’s straggling Confederates skirmished at Rockville.

Friday, July 24

In Virginia, the Federal Third Corps occupied Front Royal, and George G. Meade began concentrating his remaining forces at Warrenton. Robert E. Lee’s Confederates began arriving at Culpeper Court House, south of the Rappahannock River. Lee wrote to President Jefferson Davis that he had intended to march east of the Blue Ridge, but high water and other obstacles prevented him from doing so before the Federals crossed the Potomac into Loudoun County.

In Ohio, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates skirmished at Washington and Athens. On the South Carolina coast, Federal naval vessels bombarded Battery Wagner in Charleston Harbor as Federal infantry advanced their siege lines. Skirmishing occurred in Missouri and the New Mexico Territory.

Saturday, July 25

In Ohio, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates skirmished near Steubenville and Springfield. The Confederate Department of East Tennessee was merged into the Department of Tennessee under General Braxton Bragg. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Arkansas.

Sunday, July 26

In Ohio, John Hunt Morgan and his Confederate raiders surrendered to Federal forces at Salineville. Morgan and his men were exhausted and outnumbered after invading enemy territory and moving east near the Pennsylvania border. They were imprisoned in Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus. Morgan’s unauthorized raid had resulted in sensational headlines, the capture of nearly 6,000 Federal prisoners, the destruction of hundreds of bridges and railroad tracks, and the diversion of Federal attention from other campaigns. However, it did little to affect the war.

In Texas, prominent statesman Sam Houston died at Huntsville. Houston had opposed secession but knew that as long as the people of Texas chose to secede, they could not turn back. In Kentucky, John J. Crittenden died at Frankfort. A longtime member of Congress, Crittenden had tried to negotiate a compromise between North and South before the war.

In accordance with an act of Congress expelling the Dakota Sioux Indians from Minnesota, Colonel Henry Sibley’s Federals pursued the Lakota and Dakota Indians into the Dakota Territory and defeated them at the Battle of Dead Buffalo Lake. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Mississippi.

Monday, July 27

In Alabama, Confederate leader William Lowndes Yancey died at Montgomery. Skirmishing occurred in Kentucky, Alabama, Missouri, and Louisiana.

Tuesday, July 28

President Davis wrote to Robert E. Lee and shared his views on the recent Confederate defeats: “I have felt more than ever before the want of your advice during the recent period of disaster.” Noting that public opinion was turning against him, Davis stated, “If a victim would secure the success of our cause I would freely offer myself.”

In Virginia, General John S. Mosby’s Confederate raiders harassed George G. Meade’s Federals. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Missouri, and the Dakota Territory.

Primary source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)