Walter Coffey's Blog, page 186

June 23, 2013

Meade Replaces Hooker

In June 1863, General George G. Meade replaced General Joseph Hooker as commander of the Federal Army of the Potomac.

At the time, General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia was in the process of invading the North. Unsure of Confederate whereabouts, Hooker took eight days to leave Virginia in pursuit. The slow pace concerned Lincoln administration officials that Hooker may not be able to stop the Confederate invasion.

Hooker was infuriated when he was ordered by General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck to hold Harpers Ferry and Maryland Heights. Hooker believed that this compromised his control of the army, and he tendered his resignation in protest. To his surprise, President Abraham Lincoln accepted. Hooker was unaware that Lincoln had been waiting for a reason to relieve him of command ever since his May defeat at Chancellorsville.

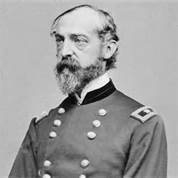

General George G. Meade

At 3 a.m. on June 28, Meade, commanding Fifth Corps, was awakened and ordered to take command of the army. Meade had no choice but to accept the tremendous responsibility and quickly formulate a strategy to stop Lee’s invasion.

By that afternoon, Meade developed a plan: “I must move toward the Susquehanna (River), keeping Washington and Baltimore well covered, and if the enemy is checked in his attempt to cross the Susquehanna, or if he turns toward Baltimore, give him battle.” Lincoln accepted Meade’s strategy and rejected panicked pleas to reinstate George B. McClellan to army command during this crucial time.Meanwhile, Robert E. Lee’s Confederates had captured Chambersburg and York. However, when Lee learned that Meade had replaced Hooker, he abandoned plans to attack Harrisburg. Instead, Lee turned back south and began concentrating his forces near Gettysburg and Cashtown. By June 30, the Federal vanguard was converging on Gettysburg from the south.

June 22, 2013

The Wilmot Proviso

In the 1840s, an amendment to a spending bill attempted to stop the expansion of slavery, but it only drove the wedge deeper between North and South.

The U.S. was at war with Mexico in 1846. When it became likely that the U.S. would win and acquire new territory in the Southwest, members of Congress began debating how the territory would be administered. This included debating over whether or not slavery should be allowed.

U.S. Congressman David Wilmot

Most politicians had tried avoiding the divisive slavery issue ever since the Missouri Compromise of 1820. But now it was starting to divide the parties. Northern Democrats were expressing dissatisfaction with their southern counterparts, particularly southern Democratic President James K. Polk. Whigs tried keeping quiet to avoid exposing sectional differences in their party as well.

On August 8, President Polk requested $2 million to negotiate an end of the war with Mexico. He explained that paying Mexico for its land would achieve an honorable peace since the U.S. had not intended to acquire territory when it declared war. Congress was scheduled to adjourn in two days, so a bill was hastily drafted. As the bill was debated in the House of Representatives, Democratic Congressman David Wilmot of Pennsylvania introduced an amendment that became known as the Wilmot Proviso.

Under Wilmot’s amendment, slavery would be prohibited in any territory acquired from Mexico. The amendment’s language was derived from the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which had administered and barred slavery in the future states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, and Illinois. Wilmot was chosen to introduce the proviso because he had consistently supported Polk and the southern Democrats.

The proviso’s introduction was not motivated by antipathy toward slavery. It was intended to keep blacks out of the new territories so that white free labor did not have to compete with black slave labor. The Wilmot Proviso introduced the notion of “free soil” in U.S. politics, or the notion that slavery should not be allowed to expand, but should be left alone where it already existed.

As an ally of slaveholders, Wilmot declared he had no “morbid sympathy for the slave,” instead submitting the proviso to uphold “the cause and the rights of white freemen.” Wilmot explained, “I would preserve to the free white labor a fair country, a rich inheritance, where the sons of toil, of my own race and color, can live without the disgrace which association with Negro slavery brings upon free labor.”

Even though it was unlikely that slavery would exist in the new territory because of the hostile southwestern climate, southerners considered the Wilmot Proviso an insult to their honor and a threat to their equality in the Union. As a result, the proviso accelerated the already growing sectional split among the political parties. The bill passed the House with the proviso attached, mainly because northerners outnumbered southerners. Northern Democrats and Whigs generally supported the bill, while southern Democrats and Whigs were opposed.

The Senate contained an equal number of northerners and southerners, and the bill passed only after Democrats removed the Wilmot Proviso. The revised bill was sent to the House for approval, but the House had already adjourned due to an eight-minute difference between the clocks in the House and Senate chambers. This meant that Congress was out of session, and the bill died.

The bill was revived when the next session of Congress began in December and Polk again asked for funding, this time $3 million. The “Three-Million Dollar Bill” was introduced in the House on February 8, 1847. The Wilmot Proviso was again included, but the language was changed from prohibiting slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico to prohibiting slavery in “any territory on the continent of America which shall hereafter be acquired.” The bill narrowly passed the House.

In the Senate, Democrat Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri sponsored a modified bill removing the Wilmot Proviso. The bill passed the Senate, and when it was returned to the House for approval, 22 Democrats reversed their original votes against the measure. The spending bill was enacted without the Wilmot Proviso.

The Mexican-American War ended in 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. When the Senate debated ratification, northern senators tried adding the Wilmot Proviso to the treaty. Stephen Douglas of Illinois argued that debate over slavery in the territories was premature because the U.S. had not yet even acquired them. Southern senators defeated the motion, and the treaty was ratified without the Wilmot Proviso. This meant that there was no ban on slavery in the territory acquired from Mexico.

Even though the Wilmot Proviso was defeated, southerners considered the measure an example of northern contempt for the southern way of life. Southerners adopted the “Alabama Platform,” which declared that the federal government had no right to interfere with slavery anywhere.

The proviso also split the Democratic Party in the 1848 elections. Democratic presidential nominee Lewis Cass opposed the Wilmot Proviso, causing proviso supporters to leave and form the Free Soil Party. This was the first political party created to directly address the slavery issue on a national level.

Cass introduced the concept of “popular sovereignty,” or the notion that settlers in the new territories should decide for themselves whether or not to allow slavery. This only caused more controversy because it made the Democrats appear to be avoiding what was now an unavoidable issue.

The Whig Party was even more ambiguous regarding slavery. They nominated General Zachary Taylor, the hero of the Mexican-American War, for president. Taylor was a southern slaveholder who made no public statements about slavery. Even so, Taylor’s war hero status and the Democratic split were enough to tip the election to him.

Many historians fail to acknowledge that the Wilmot Proviso was introduced not for concern about the plight of slaves, but for keeping the new territories open for whites only by barring slaveholders from bringing blacks into the new region. The Wilmot Proviso was one of the first steps toward the national division that ultimately led to the War Between the States.

June 19, 2013

The Divisive Pierce Administration

President Franklin Pierce’s support for southern expansion in the 1850s alienated northerners and pushed America further down the path toward civil war.

The Pierce Presidency

Franklin Pierce, 14th U.S. President

In 1852, America was splitting between North and South. To minimize the split, the Democratic Party nominated Franklin Pierce of Vermont for president. Pierce was a “doughface,” or a northerner who was sympathetic to southern views. Pierce joined southerners in favoring “manifest destiny,” or the notion that the U.S. should control North America. This was a highly popular sentiment at the time, considering the U.S. had just acquired vast new land as a result of the Mexican-American War.

With legendary author and fellow New Englander Nathaniel Hawthorne writing his campaign biography, and having served as a brigadier general in the recent war, Pierce enjoyed mass appeal in both North and South. The election was a resounding Pierce victory that virtually ended the Whig Party as a national organization. In his inaugural address, Pierce stated, “The policy of my Administration will not be controlled by any timid forebodings of evil from expansion.”

Pierce’s popularity, combined with the recent Compromise of 1850 that promised a tentative peace between North and South, should have set the stage for a successful presidency. But by the time Pierce left office four years later, his policies had only further divided the country between North and South.

The Gadsden Purchase

Pierce tried balancing his cabinet by appointing northerners and southerners, including Caleb Cushing of Massachusetts and future Confederate President Jefferson Davis of Mississippi. But they all shared Pierce’s expansionist views.

As secretary of war, Jefferson Davis sought to build a southern transcontinental railroad, both to enhance southern trade and to defend against future potential conflict with Mexico. However, the route through present-day Arizona was too mountainous. To fix this, Davis convinced Pierce to send Democratic Senator James Gadsden of South Carolina to Mexico to negotiate buying more land.

By this time, Mexican President Santa Anna had already spent most of the reparations the U.S. paid to Mexico after the Mexican-American War. Now he needed more revenue to finance his military, which made him receptive to Gadsden’s offer. Santa Anna agreed to sell a strip of land to the U.S. for $15 million. Called the Gadsden Purchase, this land consisted of present-day Arizona south of the Gila River and a portion of southern New Mexico.

Many northerners opposed the purchase because of its potential to create more slave territory. When Pierce submitted the purchase treaty to the Senate, it fell three votes short of the two-thirds majority needed for ratification. Pierce decreased the size of the acquired land and lowered the price from $15 to $10 million, and the treaty was approved. Northern senators split their vote, but unanimous southern support ensured ratification.

Santa Anna agreed to the changes, despite widespread Mexican protest that continues today. The purchase also caused sectional tension in the U.S. that ultimately doomed plans to build a southern transcontinental railroad.

The Ostend Manifesto

Before becoming president, a southern plot had begun to acquire Cuba from Spain. As a U.S. senator, Jefferson Davis had declared, “Cuba must be ours.” Southern politicians argued that the Spanish Empire was declining, and it was necessary to annex Cuba to prevent the island from falling into the hands of Britain or France.

Northerners argued that this was merely another attempt to expand southern influence in the federal government, including slavery, since the Cuban climate was conducive to a slave economy. Southerners contended that acquiring southern land was needed to offset the growing population of the North, which was resulting in northerners dominating the House of Representatives.

U.S. representatives had previously offered to buy Cuba for $100 million, but Spain had refused. When he became president, Pierce sided with the southerners on this issue. In 1854, Pierce sent ministers to Ostend, Belgium to negotiate with Spain, Britain, and France on Cuba’s future. At Ostend, the ministers were informed that a slave revolt in Cuba was imminent. They responded by sending a secret memorandum to Pierce stating that if Spain did not agree to sell Cuba to the U.S., then the U.S. should take Cuba by force in the interest of national security. When the memorandum was made public, many Americans were outraged.

Northerners vehemently protested the idea of annexing Cuba, mainly because it would give southerners more slave territory and more representation in Congress. Europeans also denounced what became known as the “Ostend Manifesto.” This incident discredited expansionism, split the Democratic Party, and so greatly damaged Pierce’s reputation in the North that he was forced to repudiate the memorandum.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act

Pierce’s favorability in the North was further damaged when he endorsed the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. This repealed the Missouri Compromise, which had banned slavery in the northern territories west of the Mississippi River, by potentially allowing slavery in the territories of Kansas and Nebraska through “popular sovereignty” (i.e., allowing the people in the territories to decide for themselves whether to permit slavery).

This law led to civil unrest in Kansas, which became a precursor to the Civil War. In endorsing this law, Pierce was roundly criticized for appeasing the South rather than trying to mend sectional disputes. As a result, the Democrats lost many seats in the 1854 mid-term elections.

No Second Term

During Pierce’s term, the Gadsden Purchase and Ostend Manifesto discredited “manifest destiny,” and the Kansas-Nebraska Act discredited “popular sovereignty.” Pierce’s ineffectiveness in handling the growing sectional crisis prompted the Democrats to decide against nominating him for a second term as president in 1856.

While Franklin Pierce had hoped to unite North and South through expansionism and appeasement, he only made sectional hostility worse by failing to recognize that America was changing. These changes ultimately led to the Civil War.

June 18, 2013

The Sons of Union Veterans: My Story

On Tuesday, June 11, I became a member of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War!

I was inducted by Lieutenant Commander Edward Lea USN, Camp 2 in Houston, Texas. You can visit the site here. The camp is named for Edward Lea, a Union naval officer who was killed during the Battle of Galveston in January 1863.

Thanks to my Aunt Barb, I learned about my ancestry and its roots in the Civil War. I am descended from Nicholas Almire, a Prussian immigrant who served in Company E of the 42nd Indiana Volunteer Infantry from 1864-65. He was drafted at age 29, and his first march was to Nashville, Tennessee. He was present at Goldsboro, North Carolina in April 1865. I don’t know if he saw action, but that was the site of the closing days of General William T. Sherman’s Union campaign through Georgia and the Carolinas.

Private Almire was honorably discharged at Louisville, Kentucky on July 21, 1865. Since the government provided no transportation, Nicholas walked home to Monticello, Indiana, hiding by day and traveling by night to avoid hostile Kentuckians. When Nicholas returned home, his wife and son didn’t recognize him because he was so thin.

Nicholas and his wife, Catherine, had one son prior to Nicholas’s service. They had at least five more children after his service. Nicholas died on January 14, 1883 from a sore on his leg that wouldn’t heal, and vomiting due to a stomach ailment. He stated that his illnesses were caused by his service in the army.

Unfortunately, Catherine’s applications for a military pension were never approved. She cared for their children and Nicholas’s ailing mother by taking in others’ laundry. She died in poverty on February 12, 1892 at age 54. Her pension claim was labeled “abandoned” and closed.

The oldest son of Nicholas and Catherine, Jacob Henry Almire, was born on August 14, 1861. He married Louisa Grisez, and they had nine children. Their fifth child was Isabella Almire. In the early 20th century, Isabella married Leonard Swansborough; the name was later shortened to Swansbro. Leonard and Isabella had a child in 1924 named Leonard, Jr., who was my grandfather. He married Rosella Alessio, and their daughter Anita is my mother.

This my heritage, and I’m honored to be a new member of the Sons of Union Veterans.

June 17, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Jun 17-23, 1863

Wednesday, June 17

In Georgia, the Confederate ironclad Atlanta, or Fingal, battled Federal ships Weehawken and Nahant at the mouth of the Wilmington River in Wassaw Sound. Atlanta was ultimately forced to surrender after being hit four times. This was a major loss for the small Confederate navy.

In Mississippi, Federal transports aiding the siege of Vicksburg were attacked by Confederates; this was one of several attacks on Federal shipping during the siege. Skirmishing occurred in Maryland as General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia continued its northward advance. Skirmishing also occurred in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri.

Thursday, June 18

In Mississippi, Federal General Ulysses S. Grant relieved General John A. McClernand as commander of Thirteenth Corps. McClernand had resented his subordinate status to Grant, arguing that his force should remain independent. Following the failed assaults on Vicksburg in May, McClernand had issued a congratulatory order to his men that disparaged the efforts of other Federal units. This gave Grant the reason he needed to dismiss him.

In Virginia, Robert E. Lee’s Confederate cavalry, commanded by General Jeb Stuart, held the approaches to the Blue Ridge. Skirmishing occurred in South Carolina, Missouri, and Louisiana

Friday, June 19

Robert E. Lee’s leading Confederate corps, commanded by General Richard Ewell, moved north of the Potomac River toward Pennsylvania. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee and Louisiana.

Saturday, June 20

President Lincoln issued a proclamation making West Virginia the 35th state. While Virginia voters had supported secession from the Union, voters in the farming and mining areas west of the Alleghenies largely opposed secession. Thus, Lincoln supported West Virginia’s secession from the rest of the state while opposing the southern secession from the rest of the Union.

Sunday, June 21

At Vicksburg, a Confederate major said, “One day is like another in a besieged city–all you can hear is the rattle of the Enemy’s guns, with the sharp crack of the rifles of their sharp-shooters going from early dawn to dark and then at night the roaring of the terrible mortars is kept up sometimes all this time.” Skirmishing occurred among Robert E. Lee’s advance units in Virginia and Maryland. Skirmishing also occurred in South Carolina, Tennessee, and Louisiana.

Monday, June 22

In Mississippi, skirmishing occurred around Vicksburg as part of the Federal siege. Also, skirmishing continued among Federals and Robert E. Lee’s advancing Confederates. Confederate raider Charles Read, captaining the captured Federal vessel Tacony, seized five Federal schooners.

Tuesday, June 23

In Tennessee, General William S. Rosecrans’s Federal Army of the Cumberland at Murfreesboro opposed General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee at Tullahoma. The Lincoln administration had been urging Rosecrans to attack, believing that this would prevent Bragg from sending reinforcements to Vicksburg. General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck finally wired Rosecrans: “I deem it my duty to repeat to you the great dissatisfaction felt here at your inactivity… Is it your intention to make an immediate move forward?” After several months of planning, Rosecrans resolved to begin advancing tomorrow.

In Louisiana, a skirmish at Brashear City resulted in the surrender of 1,000 Federals. In Virginia, General Joseph Hooker, commanding the Federal Army of the Potomac, considered crossing the Potomac River in pursuit of Robert E. Lee’s Confederates. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Mississippi, Missouri, and the Nebraska Territory.

Primary source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

June 15, 2013

Damaging Effects of the Sherman Antitrust Act

In 1890, the Sherman Antitrust Act became the first federal law to prevent “monopolistic,” “anticompetitive,” or “predatory” business practices. Sponsored by Republican Senator John Sherman of Ohio, the law was hailed as a great milestone. But its vague language failed to define what was a “monopolistic,” “anticompetitive,” or “predatory” business practice. Even worse, the law’s supposed purpose to curb big business only diverted attention from what politicians had sought all along: a high protective tariff to stifle foreign competition, which would help big business at the consumers’ expense.

Senator John Sherman

The Era of Trusts

Historians often call the late 19th century the “Gilded Age” or the “Age of the Robber Barons” based on the assumption that greedy capitalists sought to dominate emerging industries while further impoverishing the poor. However, the truth is that industries such as steel, railroads, and oil became enormous in this era because modern mass production techniques were being employed for the first time to provide basic needs and modern conveniences to more people than ever before. This created millions of jobs, which strengthened the economy and helped produce the strong middle class that became America’s backbone in the 20th century.

In their constant effort to improve efficiency, business leaders began banding together in the form of trusts. When lesser competitors failed to adopt more efficient business practices to better compete, they accused the trusts of forming monopolies and lobbied the government to stop them from being so successful. Employing class warfare, they complained that trusts were getting richer at the people’s expense, and their wealth needed to be either curtailed or confiscated. The public agreed, and politicians began exploring possible ways to regulate these trusts.

Were the Trusts Illegal Monopolies?

One of the most prevalent charges against the trusts was that they formed illegal monopolies, under which they raised prices to gain windfall profits. A “monopoly” is exclusive control of a commodity or service in a particular market, or a control that enables the manipulation of prices. So for a trust to be a “monopoly,” it had to have complete control over its products so it could decrease supply (through reduced production) to increase demand, which would force prices to rise.

However, in the decade before the Sherman Antitrust Act was passed, the industries accused of being “monopolies” grew seven times faster than the national economic growth rate. At the same time, prices charged by “monopolies” fell faster than national average price levels. For example, the Standard Oil Trust controlled about 90 percent of U.S. oil production, but oil prices were steadily falling as the trust continuously sought to improve efficiency. Why bother improving efficiency if a market is already cornered? From an economic standpoint, the trusts were not the monopolies that politicians, newspapers, and rival business leaders claimed.

Moreover, evidence suggests that even though members of Congress knew that trusts benefited consumers by expanding production, lowering prices, and creating jobs, they were concerned that the trusts were driving less efficient, higher-priced competitors out of the market. This concern came from lobbyists who pushed to protect bad business leaders. These leaders, instead of improving their businesses to better compete, lobbied Congress to pass laws weakening their stronger rivals.

Protecting “Protectionism”

John Sherman called his law the “Magna Carta of free enterprise.” But while Sherman and other politicians patted each other on the back for passing this law, the New York Times saw it for what it truly was: “That so-called Anti-Trust law was passed to deceive the people and to clear the way for the enactment of this… law relating to the tariff. It was projected in order that the party organs might say to the opponents of tariff extortion and protected combinations, ‘Behold! We have attacked the Trusts. The Republican party is the enemy of all such rings.’”

Sherman and most of his fellow Republicans were strong supporters of high tariffs (i.e., taxes) on imported goods. These taxes were intended to make domestic goods cheaper, thus diminishing competition. It was no coincidence that the Sherman Act was passed the same year as the McKinley Tariff Act, which imposed extremely high tariffs. So while the politicians seemed to be working for the people by supporting the Sherman Act, they were simultaneously raising tariffs to help big business diminish consumer choice.

The Times correctly argued that the antitrust law merely diverted attention from the real source of monopoly power: the protectionist tariff. Sherman himself declared that he supported the antitrust law because trusts “subverted the tariff system,” not because they harmed consumers. Thus the act, which was publicly touted as a tool to protect the people, was really just camouflage for raising tariffs. This ensured that special interests, political chicanery, and crony capitalism would override free enterprise.

A Big Business Win and a Consumer Defeat

Even before the Sherman Act was passed, many trusts began reorganizing into holding companies that were chartered by state legislatures. Others formed vertical combinations, in which corporations took control of every aspect of their industry. For example, Standard Oil controlled not only oil refining but railroads and ships to transport the oil, warehouses to store the oil, and raw materials to case the oil. Similarly, meatpacker Gustavus Swift owned his own cattle ranches, transportation networks, slaughterhouses, refrigerated railroad cars, and wholesale distributors. This type of top-to-bottom control reduced costs, increased profits, and created more jobs.

Ironically, the Sherman Act was invoked for the first time not against big business but against a labor union (the American Railway Union in 1894). The act was not regularly invoked until the presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft (1901-1913). In that time, several trusts were dissolved for alleged monopolistic practices, including Standard Oil in 1911.

The Sherman Antitrust Act produced two significant unintended consequences. One was that it pushed weak companies out of trusts and into either holding companies or vertical combinations. This actually strengthened business organization and made big business more powerful than ever before. Another important consequence was that instead of protecting consumers from monopoly, it protected less efficient businesses from superior competitors, which ultimately weakened the free market and harmed consumers. Both demonstrate the negative effects of political intervention in free enterprise, which continues to this day.

June 12, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Jun 10-16, 1863

Wednesday, June 10

General Joseph Hooker, commanding the Federal Army of the Potomac, wrote to President Abraham Lincoln that General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia was moving north. Hooker proposed to ignore Lee’s army and advance on the Confederate capital at Richmond. Lincoln replied, “I think Lee’s Army, and not Richmond, is your true objective point… Fight him when opportunity offers. If he stays where he is, fret him, and fret him.” Northerners were growing alarmed by news of Lee’s invasion, and the Maryland governor called on citizens to defend the state.

General Darius N. Couch assumed command of the Federal Department of the Susquehanna. General Braxton Bragg, commanding the Confederate Army of Tennessee, was confirmed in the Episcopal Church at Chattanooga. On the Virginia coast, Confederate prisoners aboard the steamer Maple Leaf ran the ship ashore and escaped. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia and Tennessee.

Thursday, June 11

In Ohio, Democrats nominated former Congressman Clement Vallandigham to run for governor. Vallandigham had been arrested and banished to the Confederacy last month for voicing opposition to the war, which made him highly popular among “Copperheads,” or Peace Democrats. However, Vallandigham was unwelcome in the South and was shipped to Canada, where he campaigned for governor while in exile.

In Louisiana, Confederate outposts were captured during the Federal siege of Port Hudson. Skirmishing occurred in South Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, and Mississippi.

Friday, June 12

The vanguard of General Lee’s Confederate army crossed the Blue Ridge into the Shenandoah Valley, where various skirmishes occurred with Federal troops. C.S.S. Clarence, commanded by Lieutenant Charles Read, captured the Federal ship Tacony off Cape Hatteras. Read transferred his crew to Tacony, destroyed Clarence, and continued pirating operations in the north Atlantic.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis approved Vice President Alexander Stephens’s plan to conduct a mission to obtain “a correct understanding and agreement between the two Governments.” This was a minor effort to negotiate a peace, but Davis and Stephens agreed that no peace could be accepted without granting each state the right “to determine its own destiny.”

In response to a complaint about arbitrary arrests and suppressions that unconstitutionally infringed upon civil liberties, President Lincoln stated, “I must continue to do so much as may seem to be required by the public safety.” General Quincy Adams Gillmore replaced General David Hunter as commander of the Federal Department of the South. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Tennessee, and Mississippi.

Saturday, June 13

In Virginia, General Lee’s vanguard drove Federals from Winchester and occupied Berryville. General Hooker’s Federals began moving north toward the Potomac River, leaving positions along the Rappahannock River they had held for nearly seven months.

President Davis asked General Bragg at Tullahoma if he could send reinforcements to the Confederates under siege at Vicksburg. Skirmishing occurred in Kentucky and Mississippi.

Sunday, June 14

Both General Hooker and President Lincoln were unaware of General Lee’s exact location. Lincoln wrote to Hooker, “If the head of Lee’s army is at Martinsburg and the tail of it on the Plank road between Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, the animal must be very slim somewhere. Could you not break him?”

As part of the Federal siege of Port Hudson on the Mississippi River, Federal General Nathaniel Banks demanded the garrison’s surrender. When the besieged Confederates refused, Banks attacked at dawn. Two Federal advances gained some ground but failed to break the lines before being repulsed with heavy losses. The campaign had cost about 4,000 Federal combat deaths, while another 7,000 had either died or fallen ill with dysentery or sunstroke. The siege of Port Hudson continued, and the defenders were growing weaker.

In Arkansas, Federal forces destroyed the town of Eunice after guerrillas attacked U.S.S. Marmora. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee.

Monday, June 15

In Virginia, the Second Battle of Winchester occurred as Lee ordered General Richard Ewell to clear the northern Shenandoah Valley of Federals as the Confederates moved north. Part of Ewell’s force captured 700 Federals, along with guns and supplies, at Martinsburg. Meanwhile, Ewell’s remaining force attacked the Federal garrison at Winchester and Stephenson’s Depot. Some Federals escaped to Harper’s Ferry, but the Confederates captured 23 guns, 300 loaded wagons, over 300 horses, and large amounts of supplies.

General Hooker informed President Lincoln that “it is not in my power to prevent” a Confederate invasion of the North. In response, Lincoln called for the mobilization of 100,000 militia from Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maryland, and West Virginia.

The Federal Navy Department dispatched a force to capture C.S.S. Tacony, the Federal ship that had been seized and used for Confederate pirating operations by Lieutenant Charles Read. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee and Louisiana.

Tuesday, June 16

General Richard Ewell’s Second Corps led the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in crossing the Potomac River from Virginia to Maryland in its northern invasion. A reporter stated that the Pennsylvania capital of Harrisburg was in a “perfect panic” as residents and politicians hurried to evacuate the city in the face of a potential Confederate invasion.

General Hooker moved most of the Federal Army of the Potomac to Fairfax Court House. Hooker argued with General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck, who wanted Hooker to follow General Lee’s Confederates and possibly relieve Harper’s Ferry. Hooker wanted to move north of Washington to confront Lee’s vanguard. When Hooker complained to Lincoln, the president instructed him to follow Halleck’s orders.

Federal troops began a campaign against the Sioux Indians in the Dakota Territory. Skirmishing occurred in Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, and the New Mexico Territory.

Primary source: The Civil War Day-by-Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

June 10, 2013

The Battle of Brandy Station

In June 1863, General Alfred Pleasonton’s Federal cavalry confronted General Jeb Stuart’s Confederates on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, along the Rappahannock River, north of Culpeper, and a few miles northeast of Fredericksburg, Virginia. For nearly 12 hours, cavalrymen charged and attacked each other at Brandy Station, Fleetwood Hill, and Beverly Ford in the largest cavalry battle in American history.

In June 1863, General Alfred Pleasonton’s Federal cavalry confronted General Jeb Stuart’s Confederates on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, along the Rappahannock River, north of Culpeper, and a few miles northeast of Fredericksburg, Virginia. For nearly 12 hours, cavalrymen charged and attacked each other at Brandy Station, Fleetwood Hill, and Beverly Ford in the largest cavalry battle in American history.

Stuart was surprised by the attack, and he barely held off the Federals at Fleetwood Hill and Stevensburg near Kelly’s Ford. Pleasonton finally withdrew his troops back across the Rappahannock near 4:30 p.m. Although this was a Confederate victory, the battle proved that the Federal cavalrymen had become effective fighters. An adjutant said that this fight “made the Federal Cavalry,” which bolstered Federal confidence. The fight also indicated to General Joseph Hooker, commanding the Federal Army of the Potomac, where the Confederates were going.

The Federals suffered 866 casualties out of about 10,000 effectives, while the Confederates lost 523 out of roughly 10,000. Despite his victory, Stuart was intensely criticized by the southern press for being caught off-guard. These criticisms may have prompted Stuart to make a bold move to restore his reputation. Misinterpreting General Robert E. Lee ’s orders, Stuart conducted a northern raid instead of shielding Lee’s advance across the Potomac River.

June 7, 2013

Andrew Jackson and the Central Bank

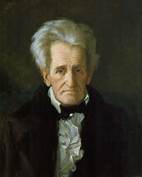

Andrew Jackson, 7th U.S. president

Can you imagine a president taking on the Federal Reserve System today? That’s what Andrew Jackson did in 1832, and it changed America forever.

The Hydra-Headed Monster

In the early 19th century, the forerunner to the Federal Reserve was the Second Bank of the United States. President Andrew Jackson despised the Bank, ostensibly because it held too much power over the economy, but truly because it was controlled by his political enemies. So Jackson set out to destroy the Bank.

The Bank had been created in a desperate attempt to stop the high debt and inflation caused by the War of 1812. However, the Bank only made matters worse by printing its own currency and extending generous (and sometimes fraudulent) loans to political friends. The loans helped cause an economic boom that crashed with the Panic of 1819, the first depression in American history. The depression soon ended, but many never forgot the Bank’s role in the crisis.

In the 1820s, the Democratic Party was formed, supposedly to represent working class voters, many of whom resented institutions that catered to the rich such as the Bank. Jackson became the first Democratic president in 1829, and he joined in on the class warfare by calling the Bank “a hydra-headed monster… it impaired the morals of our people, corrupted our statesmen, and threatened our liberty. It bought up members of Congress by the Dozen… and sought to destroy our republican institutions.”

Many perceived Jackson’s opposition to the Bank as an effort to keep government limited, to restore a sound financial system, and to free the “common man” from control by “monied elites.” However, Jackson was not opposed to central banking in general, rather he was opposed to the Bank because it was controlled by his political enemies, among them Bank President Nicholas Biddle.

Biddle and the National Republicans

Biddle routinely used lending practices for political gain, including using Bank funds to publish newspaper attacks on opponents. Biddle openly favored the National Republicans (later to become the Whig Party), many of whom benefited financially from Biddle’s favor. Prominent National Republicans were Congressmen Daniel Webster (who was on the Bank’s payroll as a legal counsel) and Henry Clay (Jackson’s opponent in the 1832 presidential election).

Demonstrating general support for central banking, Jackson offered a compromise in which the Bank would remain in operation in exchange for diminishing its power. However, Clay and Webster advised Biddle to reject the compromise because the Bank had enough support from Congress to continue operating without having to decrease its power.

To secure the Bank’s position, Clay convinced Biddle to petition Congress for re-charter in 1832, four years before the Bank’s 20-year charter was set to expire. Clay guessed that Jackson would not dare risk losing reelection by vetoing the Bank’s charter. Clay guessed wrong.

The Alarming Veto

In a strong and unprecedented veto, Jackson cited several reasons for refusing to re-charter the Bank:

It was a dangerously centralized financial power

It held an unconstitutional monopoly on finance that only helped the rich get richer

It made the economy vulnerable to foreign and special interests

It held too much influence over federal politicians

It favored the North (where most financial centers were located) over the South and West

Jackson also declared that an investigation had revealed that the Bank attempted to influence elections through fraud. He stated, “If (government) would confine itself to equal protection… it would be an unqualified blessing. (Re-chartering the Bank) seems to be a wide and unnecessary departure from these just principles.” Congress could not muster a two-thirds majority to override Jackson’s veto.

The veto was highly controversial because it was the first to use political, not just constitutional, reasons for its application. This set a precedent for future presidents to follow, which gradually expanded the power of the Executive branch of government.

“King Andrew”

National Republicans were outraged. Biddle called the veto a “manifesto of anarchy,” and Webster called it a “political tool.” Other Bank supporters denounced “King Andrew’s” tyrannical use of veto power. Meanwhile, the Bank directly contributed $100,000 to Clay’s presidential campaign and indirectly controlled thousands of potential voters through political favors.

Jackson’s opponents distributed his veto message in an effort to discredit him. However, they underestimated public resentment toward the Bank, and Jackson easily defeated Clay in the 1832 election. Upon winning a second term, Jackson pressed his advantage by ordering the withdrawal of federal funds from the Bank’s vaults. Jackson fired two Treasury secretaries before finding someone—Roger B. Taney—who carried out his order. Taney was later appointed Chief Justice of the U.S. as a reward for his loyalty.

Removing federal funds essentially killed the Bank by depriving it of the capital needed to extend loans and favors, which was its primary advantage over competitors. Jackson ordered the deposit of federal funds into state banks friendly to the Democratic Party, which were derisively called “pet banks.” The Bank of the United States sputtered along until its charter expired in 1836. Jackson’s victory was complete.

The Censure

Realizing that it was no longer the most powerful branch of government, Congress responded by censuring Jackson for assuming “upon himself authority and power not conferred by the Constitution and laws.” Shortly before Jackson left office in 1837, a more sympathetic Congress removed Jackson’s censure from the record.

Jackson’s victory over the Bank decentralized the economy and led to greater economic prosperity and individual freedom through the 1840s and 1850s. However, his devotion to patronage (i.e., granting jobs to political allies) doubled the size of the federal government during his term, which centralized political power in Washington at the people’s expense. This chipped into the prosperity and freedom generated by the end of central banking.

In the end, the central bank returned in the form of the Federal Reserve, and the size of government has increased to record levels, partly thanks to Jackson’s precedent. So individual liberty ultimately lost on both counts.

June 3, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Jun 3-9, 1863

Wednesday, June 3

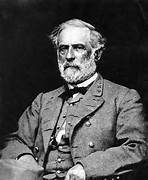

Confederate General Robert E. Lee

General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia began moving west out of Fredericksburg, beginning what would become Lee’s second invasion of the North. The Federal Ninth Corps was transferred from Kentucky to reinforce General Ulysses S. Grant’s forces laying siege to Vicksburg, Mississippi.

In New York City, Mayor Fernando Wood and other Democrats met at the Cooper Institute to call for peace. In South Carolina, the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, the first Federal black regiment, arrived at Port Royal. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia and Tennessee.

Thursday, June 4

In Virginia, two corps of Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army moved out of Fredericksburg. Upon President Abraham Lincoln’s suggestion, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton revoked General Ambrose Burnside’s order closing down the Chicago Times; the Times had been suppressed for publishing “disloyal and incendiary statements.” Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Tennessee, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Arkansas.

Friday, June 5

In Virginia, General Joseph Hooker, commanding the Federal Army of the Potomac, exchanged wires with President Lincoln and General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck about Robert E. Lee’s movement. Hooker wanted to attack Lee’s remaining Confederates at Fredericksburg, while Lincoln and Halleck wanted Hooker to attack Lee’s forces moving west.

Saturday, June 6

In Virginia, General Jeb Stuart, commanding Robert E. Lee’s Confederate cavalry, staged a grand review for Lee and other top Confederate officers, dignitaries, and ladies near Culpeper. The review raised noise and dust that was spotted by the Federals.

President Lincoln expressed concern about delayed telegrams from Vicksburg. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Louisiana, and the Indian Territory.

Sunday, June 7

In Mississippi, a Confederate attack at Milliken’s Bend was repulsed, and Federals captured and burned Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s plantation, Brierfield. These actions helped to slowly strangle Vicksburg into submission. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia and Kentucky.

Monday, June 8

In Mississippi, the punishing Federal siege of Vicksburg continued. A resident wrote of the endless artillery bombardment, “Twenty-four hours of each day these preachers of the Union made their touching remarks to the town. All night long their deadly hail of iron dropped through roofs and tore up the deserted and denuded streets.” Residents moved into caves on the town’s hillsides for refuge. Supplies dwindled and hungry people resorted to eating mules, dogs, cats, and rats.

In Virginia, Jeb Stuart staged another grand cavalry review for top Confederate officials that attracted Federal attention. Joseph Hooker dispatched cavalry and infantry under General Alfred Pleasonton to “disperse and destroy the enemy force.” Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, Missouri, and Kansas.

Tuesday, June 9

In Virginia, the Battle of Brandy Station occurred as Alfred Pleasonton’s Federals attacked Jeb Stuart’s Confederate cavalry along the Rappahannock River, north of Culpeper. The lines surged back and forth for nearly 12 hours. Surprised by the attack, Stuart barely held off the Federals until Pleasonton finally withdrew. Although this was a Confederate victory, the battle proved that the Federal cavalrymen had become effective fighters. This bolstered Federal confidence and indicated to Joseph Hooker that the Confederates were moving north.

A powder magazine explosion killed 20 Federals and wounded 14 in Alexandria, Virginia. In Tennessee, two soldiers were hanged by Federals as spies. Skirmishing occurred in Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana.