Walter Coffey's Blog, page 185

July 21, 2013

Civil War News Book Review

Below is a review of my book from “Civil War News.” I appreciate the reviewer bringing to my attention some details I might have missed, though I’m not sure about the error regarding A.P. Hill’s role at Harpers Ferry before Antietam. But I disagree with criticism of my premise that the war was caused by money and politics, not slavery.

The reviewer cites the ordinances of secession to argue that the southern states left the Union because they wanted to preserve slavery. I don’t dispute this point. However, just because slavery caused the secession doesn’t mean that it also caused the war. I still contend that money and politics caused the war, and although slavery played a key role in both, it wasn’t the main cause of the conflict. This is clearly explained in my book’s introduction.

The reviewer also compares my premise to the “dubious” work of economist Thomas DiLorenzo, who has been criticized for his negative assessment of Abraham Lincoln. Well I consider it a compliment to be compared to Thomas DiLorenzo, who is an excellent champion of free markets and constitutional liberty. And just because he committed the “ultimate sin” by daring to criticize Lincoln doesn’t mean that he’s wrong.

By John Foskett:

This book by Walter Coffey is a chronological history of the Civil War. Each chapter is devoted to one month, beginning with January 1861 and ending with May 1865. The chapters are not broken down by dates but rather by topical paragraphs regarding the most significant events during each month.

Battles and campaigns are covered, of course, but so are political events, economic developments, legislative and executive actions, and issues arising on the home fronts. These entries are succinct and are intended to convey basic information to readers with a casual interest in the war and all of its facets.

Given the book’s apparent audience, there are some concerns. While the author has capably chosen a comprehensive cross-section of important events and developments, “the devil is in the details.”

There are numerous errors. For example, the Confederate forces that captured Harpers Ferry in September 1862 were commanded by Stonewall Jackson, not A.P. Hill; the primary problem caused by Union Maj. General Dan Sickles’ tactical decision at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863, was that it isolated his corps from its supports, rather than isolating the Round Tops;

James Longstreet commanded the Army of Northern Virginia’s First Corps, not its Third Corps, at the Battle of the Wilderness; and the long-held legend that 7,000 Union soldiers became casualties in half an hour during the June 3, 1864, assault at Cold Harbor was debunked some years ago by historian Gordon Rhea.

The author’s introduction regarding the causes of the war also raises questions. Asserting that the “true cause” was not slavery but, instead, “money and politics,” the author focuses on U.S. tariffs and their disproportionate effect on the South.

This approach appears to be straight from dubious theories advanced by economist Thomas J. DiLorenzo. Those theories turn more on opinion and modern political philosophy than they do on historical evidence.

That evidence includes the texts of the seceding states’ secession resolutions. It also includes the writings and speeches of the secession commissioners from the lower South during the winter of 1860-61.

Reading the resolutions and the commissioners’ arguments for disunion to their recalcitrant brethren farther north leaves little doubt that discontent with tariffs and the philosophy of state’s rights took second chair as a basis for secession to fears about Northern intentions towards the South’s “peculiar institution.”

There is no bibliography. Instead the author supplies a list of “recommended reading.” That list contains a random sampling of secondary sources, some popular published primary sources, and a few idiosyncratic books such as two uniformly criticized volumes by DiLorenzo on Abraham Lincoln.

Readers with a thorough grounding can apply their trained eyes to errors of detail and analysis. As noted, however, they do not appear to be the targeted audience. Civil War buffs and serious students are far better served by the “gold standard” for this type of work, which remains E.B. Long’s 1971 The Civil War Day by Day.

Coffey’s book is acceptable for the casual reader who comes to it with some basic background knowledge, especially since it introduces that reader to significant non-military events with which he or she likely is not familiar.

July 17, 2013

The Cuban Missile Crisis

The U.S.S.R. capitalized on President John F. Kennedy’s weakness to push the world to the brink of nuclear war.

In October 1962, U.S. officials discovered that the U.S.S.R. was building missile systems in Cuba, close enough to strike U.S. soil. For 13 days, Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev faced off to see which superpower would flinch first.

The Bay of Pigs

In April 1961, three months after President Kennedy took office, a small force of Cuban exiles invaded Cuba at the Bahia de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs) to overthrow communist dictator Fidel Castro. The U.S. had pledged to assist the exiles with a naval fleet and warplanes, and Kennedy had approved the plan.

But Castro anticipated the invasion, having announced on Radio Havana that Kennedy’s recent State of the Union address indicated “a new attack on Cuba by the United States.” When the invasion faltered, Kennedy withheld the promised naval and air support, and all the invaders were either killed or captured. Humiliated, Kennedy had to negotiate for the captives’ release.

The Bay of Pigs debacle was the result of a lack of training, planning, communication, and equipment. This fiasco damaged U.S. prestige among its allies and increased tensions between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. It also enabled Castro to denounce the U.S. as aggressors and strengthen his ties to the Soviets. Soviet Premier Khrushchev saw this as a sign of Kennedy’s weakness and began planning to arm Cuba more heavily.

Signs of Weakness in Europe

Khrushchev’s assessment that Kennedy could be easily intimidated was enhanced at a 1961 summit meeting between the two leaders in Vienna, where even Kennedy admitted that Khrushchev had pushed him around. This emboldened the Soviets to tighten their grip on Eastern Europe, which led to the building of the Berlin Wall.

The Berlin Wall separated communist East Berlin from democratic West Berlin in East Germany. The wall stopped the desperate flow of refugees from the East to the West. West Berliners expressed frustration that Kennedy did nothing to stop the wall from being built. Even though there was little that Kennedy could have done since the wall did not justify going to war, the presumption that Kennedy allowed the wall to go up enhanced his reputation as a weak leader.

This prompted the Soviets to make their biggest gamble of the Cold War: installing offensive nuclear weapons in Cuba.

The Missile Discovery

On October 14, 1962, photographs taken by U-2 spy planes revealed 65 Soviet missile sites in Cuba. These included not only intermediate-range ballistic nuclear missile sites (IRBMs), but also surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) protecting the sites. These bases were capable of launching missiles that could destroy major U.S. communications systems before a retaliatory strike could be ordered. The missiles could also strike many major U.S. cities and kill tens of millions of Americans within minutes.

Executive Committee Meeting to Discuss the Discovery of Missiles in Cuba

When Kennedy received the photographs on October 16, he immediately consulted with his advisors and cabinet. A response to this threat was needed to both protect the U.S. and stop Soviet expansion in the Western Hemisphere. If Kennedy did nothing, then Americans would live under the threat of nuclear attack at close range, and the country’s international reputation would be permanently weakened. It would also embolden world communism. If the U.S. attacked Cuba, it could spark a nuclear war with the U.S.S.R.

Kennedy’s cabinet was almost evenly divided on what his response should be. Some urged an immediate air strike and invasion. Some urged having the United Nations impose sanctions on Cuba and the U.S.S.R. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy proposed a naval blockade of Cuba to prevent the importation of materiel needed to complete the weapons systems. Robert Kennedy’s proposal was based on a CIA report contending that a blockade would not ignite a war if the president could prove that it was a direct response to Soviet aggression. Perhaps more importantly, a blockade could give the Soviets the opportunity to withdraw on their own terms and avoid a direct confrontation.

The Negotiations

After listening to various opinions, President Kennedy delivered a televised address on October 22. He announced that the Soviets had installed missile bases in Cuba, capable of sending nuclear missiles 1,000 miles into the U.S. Kennedy warned that any attempt to place nuclear weapons in Cuba would be considered a threat to the U.S., and while the U.S. did not seek war, it would not tolerate the installation of Soviet missiles in Cuba.

To stop the missile installation, Kennedy proclaimed a naval blockade, or “quarantine,” under which all ships arriving in Cuba would be inspected by the U.S. Navy. The Soviets were given until October 24 to dismantle the systems already in place, and Kennedy ordered the military to prepare for an invasion if the Soviets did not comply. After the speech, Kennedy began negotiations with Khrushchev through an intermediary from ABC News.

Kennedy insisted that Khrushchev return to the “earlier situation” before the missile bases had been installed. As Soviet ships approached Cuba, Khrushchev warned that the U.S.S.R. would not accept the blockade. People around the world anxiously awaited a confrontation as the ships drew nearer.

On October 26, Khrushchev sent a secret message to Kennedy offering to withdraw the missile bases in exchange for a U.S. pledge not to invade Cuba. Shortly after sending this message, Khrushchev sent a second message demanding that the U.S. also dismantle its missile bases in Turkey. But Kennedy pretended not to have received it while accepting the terms of the first.

Castro urged Khrushchev to launch a “pre-emptive” nuclear attack on the U.S., but Khrushchev refused. The U.S. tried to negotiate with Castro through Brazilian intermediaries, but Castro refused. When Khrushchev agreed to dismantle the missile sites based on Kennedy’s pledge not to invade Cuba, Castro was enraged.

The Agreement

Ultimately a secret deal was struck, under which the U.S.S.R. would dismantle the missile sites in Cuba and the U.S. would not invade Cuba. In addition, a telephone hotline between Washington and Moscow would be installed to ensure better communication, and a nuclear test ban treaty would be negotiated. And the U.S. secretly agreed to Soviet demands to dismantle its bases in Turkey, mainly because the sites were obsolete due to advances in nuclear submarine technology.

Radio Moscow announced that the missiles in Cuba would be crated and returned to the U.S.S.R., and Khrushchev ordered the Soviet ships heading to Cuba to turn back from the U.S. blockade line. The U.S. blockade of Cuba ended on November 20. The “Cuban Missile Crisis” brought the world closer to nuclear war than ever before, and its resolution brought immense relief.

Aftermath

Kennedy’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis proved to Khrushchev that the president was not as weak as previously believed. The U.S. media hailed Kennedy as a tough young leader who forced the mighty U.S.S.R. to back down. However, little was mentioned about how Kennedy’s prior weakness played a key role in starting this crisis in the first place.

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a humiliation for the U.S.S.R., which had been goaded by Cuba into overextending itself and was forced to withdraw. When Soviet intelligence revealed that the U.S. Navy could have destroyed the Soviet Atlantic fleet in minutes, the U.S.S.R. began modernizing and expanding its navy. Moreover, intelligence from a Soviet defector showed that U.S. nuclear weaponry was far superior to the Soviets’, despite Kennedy’s false campaign claim of a “missile gap” in the Soviets’ favor.

The U.S. success prompted many Cubans to flee to the U.S., where many flourished in a capitalist economy while Cuba languished in poverty under communist oppression. However, it also caused the highest increase in U.S. military expenditures since the Korean War, and it emboldened U.S. military leaders to urge even more spending to stop the spread of communism. This, combined with Kennedy’s determination to maintain his new tough image, soon turned U.S. attention to Vietnam.

July 15, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Jul 15-21, 1863

Wednesday, July 15

In Ohio, General John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates continued moving east of Cincinnati toward the Ohio River as Federals pursued. In Virginia, General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia slowly moved south up the Shenandoah Valley. In Mississippi, General William T. Sherman’s Federals increased pressure on Confederates under General Joseph E. Johnston at the state capital of Jackson.

President Lincoln issued a proclamation designating August 6 as a day of praise, prayer, and thanksgiving for the recent military victories. To Confederate General Theophilus H. Holmes in the Trans-Mississippi Department, President Jefferson Davis confided, “The clouds are truly dark over us.”

In New York City, order was gradually being restored after three days of violent rioting. In Kentucky, Federals occupied Hickman. Skirmishing occurred in West Virginia and Tennessee.

Thursday, July 16

U.S.S. Wyoming Captain James S. McDougal destroyed Japanese batteries in the Straits of Shimonoseki after learning that Japan was expelling foreigners and closing the Straits. Wyoming had stopped at Yokohama during her search for famed Confederate commerce raider C.S.S. Alabama. This was the first naval battle between the U.S. and Japan, and an international naval squadron later forced Japan to reopen the Straits.

In Mississippi, Joseph E. Johnston abandoned Jackson to William T. Sherman’s Federals after being outnumbered and outmaneuvered. On the South Carolina coast, Federal army and navy forces repulsed a Confederate assault near Grimball’s Landing on James Island. In Louisiana, the steamer Imperial became the first Federal vessel to successfully travel down the Mississippi River from St. Louis to New Orleans in over two years.

In Virginia, Robert E. Lee wrote to Jefferson Davis, “The men are in good health and spirits, but want shoes and clothing badly… As soon as these necessary articles are obtained, we shall be prepared to resume operations.” Skirmishing occurred in West Virginia, Tennessee, and Mississippi.

Friday, July 17

In Ohio, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates met stiff Federal resistance near Hamden and Berlin as they continued trying to reach the Ohio River. In Virginia, a cavalry skirmish occurred at Wytheville. Other skirmishing occurred in West Virginia, Tennessee, and Mississippi.

In the Indian Territory, General James G. Blunt’s Federals attacked Confederates under General Douglas H. Cooper in the largest engagement in the region. The Confederates withdrew due to lack of ammunition in a battle that featured black Federals opposing Confederate Indians.

Saturday, July 18

On the South Carolina coast, Federals continued efforts to capture Charleston. The harbor was pummeled by artillery before about 6,000 Federals launched a frontal attack on Fort Wagner on the south end of Morris Island. Leading the assault was the 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry regiment. A portion of the Confederate earthworks was temporarily captured, but the attack was ultimately repulsed with heavy losses. This Federal defeat proved that Charleston could not be taken by a joint Army-Navy force without first conducting a siege. Despite the defeat, this effort earned fame for the 54th and legitimized the role of blacks as U.S. soldiers.

In Ohio, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates were becoming desperate due to relentless Federal pursuit and pressure. They reached Buffington on the Ohio River, but it was guarded by Federals and Morgan had to wait until next morning to try crossing back into Kentucky.

In Indiana, George W.L. Bickley, a leader of the Knights of the Golden Circle, was arrested. President Lincoln commuted several sentences for soldiers found guilty of various crimes.

President Davis called for enrollment in the Confederate army those coming under jurisdiction of the Conscription Act. General John G. Foster assumed command of the Federal Department of Virginia and North Carolina, and General John A. Dix assumed command of the Federal Department of the East. Skirmishing occurred in West Virginia, Mississippi, Louisiana, and the New Mexico Territory.

Sunday, July 19

In Ohio, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates attacked Buffington in an effort to cross the Ohio River, but Federals repulsed them. The Confederates suffered over 800 casualties, including 700 captured. Morgan’s remaining 300 men continued along the Ohio toward Pennsylvania.

General George G. Meade’s Federal Army of the Potomac completed crossing the Potomac River into Virginia in their pursuit of Robert E. Lee. General D.H. Hill replaced General William Hardee as commander of Second Corps in General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee. Skirmishing occurred in Mississippi and the New Mexico Territory.

Monday, July 20

In Ohio, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates skirmished near Hockingport as they turned northward away from the Ohio River. In Virginia, skirmishing occurred between George G. Meade’s Federals and Robert E. Lee’s Confederates.

On the South Carolina coast, Federal naval forces bombarded Legare’s Point on James Island. Skirmishing occurred in North Carolina and the Indian Territory.

The Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce expelled 33 members for refusing to take an oath of allegiance. New York merchants gathered to organize relief efforts for black victims of the draft riots.

Tuesday, July 21

In Virginia, skirmishing continued between George G. Meade’s Federals and Robert E. Lee’s Confederates. President Lincoln wrote to General O.O. Howard describing George G. Meade “as a brave and skillful officer, and a true man.” Lincoln directed Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to renew vigorous efforts to raise black troops along the Mississippi River.

President Davis wrote to Robert E. Lee expressing concern over the defeat at Gettysburg and the Federal threat to Charleston, South Carolina. General John D. Imboden was given command of the Confederate Valley District. Skirmishing occurred in North Carolina.

Primary source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

July 14, 2013

Vetoing the Bonus Bill

Back when the Constitution was taken literally, President James Madison vetoed a measure that would have established a national public works program.

4th U.S. President James Madison

After its creation in 1816, the Second Bank of the United States awarded a $1.5 million bonus in surplus revenue to the U.S. Treasury. In early 1817, Congress passed a measure to spend the money called the Bonus Bill. Sponsored by Congressman John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, the bonus would fund a national program of improving roads, canals, harbors, and defense to better facilitate interstate commerce.

This bill was popular among southerners and westerners because most of the projects that were proposed would take place in their states. New Englanders opposed the bill because it could encourage western expansion, which would diminish New England’s political influence in the federal government.

The concept of providing federal tax dollars for “internal improvements” had been debated since America’s founding. Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. Treasury secretary, supported providing “bounties” to preferred businesses to stimulate the economy and establish an alliance between government and business. Hamilton’s legacy was continued by new young congressmen such as Congressman Henry Clay of Kentucky, who introduced what became known as the “American System.”

The “American System” was a national economic program composed of high tariffs on imports to protect domestic manufacturing, centralized banking to better regulate the economy, and funding preferred businesses to improve the national infrastructure. This program threatened the federal system of government created by the Constitution by transferring power from the states to the national government.

In his last official act, President Madison, known as the “Father of the Constitution,” vetoed the Bonus Bill. In his veto message, Madison stated, “I am constrained by the insuperable difficulty I feel in reconciling the bill with the Constitution of the United States… The legislative powers vested in Congress are specified and enumerated in the eighth section of the first article of the Constitution, and it does not appear that the power proposed to be exercised by the bill is among the enumerated powers.”

Madison had endorsed the first two planks of the “American System” the previous year when he approved a high tariff law and a law creating the Second Bank of the United States. Madison had initially believed that protective tariffs and central banking were unconstitutional as well, but he reluctantly approved them in an effort to stimulate the struggling economy after the War of 1812. Madison drew the line with approving the third plank of the program.

Madison asserted, “I am not unaware of the great importance of roads and canals and the improved navigation of water courses, and that a power in the National Legislature to provide for them might be exercised with signal advantage to the general prosperity.” However, Madison contended that the Constitution would need to be amended to enact such an ambitious program.

Although the bill was defeated, Congress continued passing similar measures until future presidents eventually began approving them. Most internal improvement projects were approved based on the federal government’s constitutional power to regulate interstate commerce. There has never been a constitutional amendment to clearly establish that the federal government has the power to use taxpayer money to subsidize preferred businesses, even when they are performing valuable public works.

Since Madison’s time, the practice of funding internal improvements has become known as “pork-barrel spending” or “corporate welfare.” The politics that have become infused with such spending has led to massive expenditures that have helped incur the enormous national debt that stands today.

July 8, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Jul 8-14, 1863

Wednesday, July 8

General John Hunt Morgan’s Confederate raiders crossed the Ohio River west of Louisville and entered Indiana after destroying supply and communication lines. Citizens panicked, fearing that local Copperheads would join Morgan’s attack.

In Louisiana, Confederates under siege at Port Hudson on the Mississippi River learned of Vicksburg’s surrender. Realizing that hope was lost, Confederate General Franklin Gardner asked Federal General Nathaniel Banks for surrender terms.

General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia reached Hagerstown, Maryland. Lee wrote to President Jefferson Davis that he was “not in the least discouraged” by the defeat at Gettysburg last week.

Skirmishing occurred in Mississippi as General William T. Sherman’s Federals advanced on the state capital at Jackson. In Massachusetts, the Federal military draft began.

Thursday, July 9

In Louisiana, Franklin Gardner unconditionally surrendered his 7,208 remaining men at Port Hudson after enduring a six-week siege. The fall of Vicksburg on July 4 had isolated Port Hudson on the Mississippi River, making surrender inevitable. This opened the entire Mississippi to Federal navigation and split the Confederacy in two.

In Indiana, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates raided homes and businesses in Corydon. In Mississippi, skirmishing continued between William T. Sherman’s Federals and Confederates under General Joseph E. Johnston. Jefferson Davis wrote to Johnston expressing hope that the Federals “may yet be crushed and the late disaster could be repaired by a concentration of all forces.”

Friday, July 10

In South Carolina, Federal naval forces bombarded Charleston in an effort to seize the vital harbor. As part of the effort, Federal infantry under General Quincy A. Gillmore targeted a prime harbor defense point: Battery or Fort Wagner on the south end of Morris Island. Jefferson Davis wrote to South Carolina Governor M.L. Bonham to send local troops to Charleston to defend against the Federal attacks. In addition to escalated Federal attacks on Charleston, the Confederacy was reeling after losses at Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Tullahoma, and Port Hudson.

In Indiana, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates skirmished at Salem before turning east toward Ohio. Skirmishing occurred at various points between Robert E. Lee’s Confederates and General George G. Meade’s Federal Army of the Potomac. Lee’s troops reached the Potomac River in their effort to return to Virginia.

Saturday, July 11

In South Carolina, a Federal attack on Fort Wagner was repulsed by Confederate defenders. Jefferson Davis wrote to Joseph E. Johnston that since both Generals P.G.T. Beauregard at Charleston and Braxton Bragg at Chattanooga were under threat, “The importance of your position is apparent, and you will not fail to employ all available means to ensure success.”

In Maryland, Robert E. Lee’s Confederates established defensive positions along the Potomac River because George G. Meade’s Federals were approaching and the river was too high to ford. In Mississippi, William T. Sherman’s Federals reached the outskirts of Jackson.

In New York City, the first names of men eligible for the Federal military draft were randomly drawn by officials in the Ninth District Provost Marshal’s office at Third Avenue and 46th Street. The names were published in city newspapers. The notion of being forced into the military added to growing northern resentment of both the war and the Lincoln administration. That resentment was especially strong in New York, where Governor Horatio Seymour denounced Abraham Lincoln’s unjust war and unconstitutional attacks on civil liberties.

Sunday, July 12

In Maryland, George G. Meade’s Federals prepared to attack Robert E. Lee’s Confederates near Williamsport. However, the Potomac River was falling, and Lee began planning to cross the next day.

In Mississippi, William T. Sherman’s Federals skirmished near Canton. In Indiana, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederate invasion was losing momentum due to straggling troops and resistance from angry citizens.

Monday, July 13

In New York City, an enraged mob attacked the Ninth District Provost Marshal’s office where the military draft was being conducted. The mob used stones, bricks, clubs, and bats. Officials were beaten and the building was burned. The police tried to stop the violence, but they were quickly overwhelmed by the enormous mob.

The three-day rampage resulted in the burning of businesses, hotels, police stations, the mayor’s home, and the pro-Republican New York Tribune office. Blacks were beaten, tortured, and killed, including a crippled coachman who was lynched and burned as rioters chanted, “Hurrah for Jeff Davis.” The Colored Orphan Asylum was burned, but police saved most of the orphans. A heavy rain helped extinguish the fires, but the riot continued for two more days. Riots also occurred in Boston; Portsmouth, New Hampshire; Rutland, Vermont; Wooster, Ohio; and Troy, New York.

John Hunt Morgan’s Confederate raiders entered Ohio and captured Harrison. Morgan initially planned to attack either Hamilton or Cincinnati, but due to growing Federal resistance, he decided to return south. Federal authorities declared martial law in Cincinnati. In Maryland, Robert E. Lee’s Confederates began crossing the Potomac River into Virginia during the night.

In Mississippi, Federals occupied Yazoo City and Natchez without a fight. Texas Governor F.R. Lubbock wrote to Jefferson Davis requesting more arms to defend the state. President Lincoln wrote to General Ulysses S. Grant congratulating him on his capture of Vicksburg. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee and Louisiana.

Tuesday, July 14

In New York, workers joined the rioters in attacking the homes of prominent Republicans. Governor Seymour unsuccessfully tried to stop the violence. An announcement suspending the draft eased the riot somewhat, but it continued into the next day.

In Maryland, George G. Meade’s Federals advanced on the Confederate defensive works but found them abandoned, as Robert E. Lee had withdrawn across the Potomac last night. President Lincoln wrote a letter to Meade that he never signed or sent, stating “Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasureably (sic) because of it.”

In Ohio, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates skirmished near Camp Dennison. General W.H.C. Whiting was appointed commander of the Confederate Department of North Carolina. Jefferson Davis wrote to Senator R.W. Johnson, “In proportion as our difficulties increase, so must we all cling together, judge charitably of each other, and strive to bear and forbear, however great may be the sacrifice and bitter the trial…”

Primary Source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

July 7, 2013

The South Carolina Nullification

South Carolina’s response to perceived onerous federal taxation led to one of the first major sectional conflicts in U.S. history and helped sow the seeds of civil war.

In 1828, a new tariff law was enacted that raised taxes on foreign imports to unprecedented levels. The law’s supporters were mostly northerners who believed that higher taxes on imports would protect northern industrial goods from European competition.

However, the law disproportionately harmed the South because that region relied more on foreign imports than the North. In addition, high tariffs could prompt foreign trading partners to retaliate with high tariffs of their own, which could disproportionately harm the South because southerners relied more on exporting their goods than northern manufacturers.

In reality, the tariff was not raised to protect U.S. industry. It was a political ploy to help Andrew Jackson get elected president. Exorbitant taxes were placed on goods manufactured in New England, which was the home of current President John Quincy Adams. When Adams signed the bill into law, he was accused of favoring New Englanders over southerners, and his prospects for reelection in the upcoming presidential election became slim.

Southerners condemned this new law, calling it the “Tariff of Abominations.” An anonymous pamphlet called “The South Carolina Exposition and Protest” was distributed that declared the tariff was “unconstitutional, oppressive and unjust.” According to the pamphlet, “The United States is not a union of the people, but a league or compact between sovereign states, any of which has the right to judge when the compact is broken and to pronounce any law null and void which violates its conditions.” The tract’s author was later revealed to be Vice President John C. Calhoun of South Carolina.

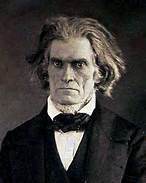

John C. Calhoun of South Carolina

Calhoun’s theory of nullification was not an original idea. The original nullification document was the Declaration of Independence, in which Thomas Jefferson proclaimed that the states were independent of Great Britain and therefore no longer subject to her laws. Jefferson and James Madison also encouraged state resistance to federal authority in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolves of 1798. In addition, many northerners also supported nullification, especially abolitionists who urged people to ignore laws that upheld and enforced slavery.

Many founders believed that since the federal government derived its power from the states’ consent, the states had the inherent right to defy federal laws considered harmful to their existence. Much state resistance to federal power stemmed from the War for Independence, which was a war of secession from Great Britain. American fears of a tyrannical central government prompted many to declare greater loyalty to their state than the federal authority. To southerners, an unfairly high tariff constituted federal tyranny.

As planned, Andrew Jackson was elected president shortly after John Quincy Adams approved the high tariff. Southerners supported Jackson in the hope that as a fellow southerner, he would be sympathetic to their interests. When prospects of the desired sympathy turned bleak, cries grew louder for nullification, and Vice President Calhoun declared support for the nullifiers.

Tensions between Calhoun and Jackson climaxed at the annual Jefferson’s Birthday Dinner in 1830. Proposing a toast, Jackson declared, “Our Union! It must be preserved!” Calhoun countered by declaring, “The Union! Next to our liberty, the most dear!” The following year, Calhoun delivered a speech:

“Stripped of all its covering, the naked question is, whether ours is a federal or consolidated government; a constitutional or absolute one; a government resting solidly on the basis of the sovereignty of the states, or on the unrestrained will of a majority; a form of government, as in all other unlimited ones, in which injustice, violence, and force must ultimately prevail.”

Calhoun ultimately became the first vice president to resign when the South Carolina legislature elected him to the U.S. Senate. Calhoun encouraged his fellow South Carolinians to oppose federal enforcement of the tariff.

In an effort to ease the bitterness, a new tariff law was enacted in 1832. Although this generally lowered the tariff rates, the decreases were not enough to appease South Carolina. On November 24, a state convention passed an “Ordinance of Nullification” which declared the tariff “null, void and no law.”

President Jackson furiously declared that no state could nullify a federal law and he initiated the Force Act, which empowered him to mobilize the U.S. military to collect tariffs if necessary. Jackson ordered General Winfield Scott to prepare to lead 50,000 troops into the state, and he ordered a naval squadron at Norfolk to prepare to go to Charleston. South Carolina officials condemned “King Andrew” and mobilized 10,000 state militia to repel a potential invasion. Meanwhile, politicians led by Calhoun and Henry Clay scrambled to find a compromise to avert war.

Congressmen eventually agreed upon a new law known as the Compromise Tariff of 1833. This gradually reduced taxes on imports over 10 years in exchange for South Carolina revoking the Ordinance of Nullification. After all parties agreed to the terms, South Carolinians symbolically voted to nullify Jackson’s Force Act. It was a final act of defiance, even though the Force Act was never implemented.

Both sides claimed victory in the tariff standoff. Some saw this as a defeat for the theory of nullification, and others saw it as a southern victory because tariffs were ultimately lowered. Many southern states began citing this incident as an example that states were empowered to secede, and the flames of secession began growing hotter. While the compromise temporarily pacified both sides, the tariff would be one of key issues that would divide the North and South for the next 30 years and lead to civil war.

July 5, 2013

Annexing San Domingo

U.S. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts

Less than two years after the Civil War ended, expansionists sought to acquire the island nation of San Domingo, which is now known as the Dominican Republic. Senator Charles Sumner defied the president and his own party to oppose depriving an independent nation of its own self-determination.

By the late 1860s, U.S. politicians had long desired to expand beyond North America for some time, especially in the Caribbean Sea where European merchants competed with the U.S. for commerce. Some thought that expanding into the Caribbean would eventually lead to the U.S. conquering Mexico and Canada and controlling the whole Western Hemisphere.

In 1867, Secretary of State William Seward negotiated treaties to buy the Danish West Indies (the present-day Virgin Islands) and the valuable naval port of Samana Bay in San Domingo. The Senate rejected both treaties, but the expansionists persisted.

When Ulysses S. Grant became president in 1869, he authorized his personal secretary, Orville E. Babcock, to negotiate a treaty with President Buenaventura Baez of San Domingo. Both sides agreed that the U.S. would acquire San Domingo (which would eventually become a state), lease Samana Bay for $150,000, and pay $1.5 million toward San Domingo’s national debt.

Grant strongly supported annexing San Domingo because Samana Bay could become a key naval base for the U.S. navy to control the Caribbean. Also, the island nation was rich with minerals and sugar cane. U.S. business interests on the island supported annexation for financial reasons, and President Baez supported annexation to save himself from being overthrown in a revolt that was taking place against his regime.

More importantly, Grant believed that San Domingo could provide a sanctuary where former slaves in the South could go to escape white injustice. This was consistent with the Republican Party idea that colonizing blacks outside the U.S. would solve the country’s racial problems.

The treaty was negotiated in secret, and it was later revealed that Babcock, who was not a diplomat, stood to profit from annexation because he owned land on the island. Babcock also interfered with the San Domingo civil war by ordering a U.S. navy ship to block anti-Baez vessels from threatening the island’s coast. Baez’s regime was propped up by the U.S. military while negotiations proceeded.

In San Domingo, a popular election was held to determine whether or not to approve annexation to the U.S. Voters were threatened with exile or execution if they opposed the treaty. Predictably, it was approved almost unanimously. The rebels fighting to free themselves from Baez’s oppressive regime were branded terrorists by U.S. officials for opposing annexation.

In the U.S., Grant knew that the treaty would only be approved in the Senate if it was supported by Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, the powerful chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee. However, Sumner opposed the treaty. He expressed concern that the U.S. would inherit San Domingo’s vast debt, which could require the U.S. military to prevent creditor nations from seeking reimbursement by force.

Sumner also noted that annexation would involve the U.S. in the ongoing conflict between San Domingo and neighboring Haiti, which were the only two black republics in the world. He advised that the black nations “should not be absorbed by the United States, but should remain as independent powers, and should try for themselves to make the experiment of self-government.” From a political standpoint, Sumner joined many of his fellow New Englanders in opposing any U.S. expansion to the south, which would move the political center of the U.S. away from New England.

Republicans had traditionally opposed southern expansion because it would extend slavery, but now that slavery was abolished, most of them reversed course. Democrats resisted bringing more blacks into the U.S., with some arguing that the tropical climate made the people habitually lazy and unable to govern themselves.

After repeated urgings from Grant, the Senate finally voted. The tally was 28 for and 28 against, which fell far short of the two-thirds majority needed for ratification. Grant felt betrayed because he thought he had garnered Sumner’s support.

Grant would not accept defeat. He removed cabinet members who opposed the treaty, he removed a top diplomat who was friends with Sumner, and he began looking into having Sumner removed as committee chairman. When Congress assembled in December 1870, Grant asked the Senate to reconsider the treaty. Sumner again voiced strong opposition, arguing that the U.S. would be committed “to a dance of blood” by involving the U.S. in San Domingo’s civil turmoil. Sumner also condemned President Baez, who was only “sustained in power by the (U.S.) that he may betray his country.”

The Senate overruled Sumner and created a commission to go to San Domingo to determine the feasibility of annexation. The commission consisted of pro-annexationists, so they predictably supported acquiring San Domingo. And when the next Congress assembled in 1871, Grant’s allies in the Senate voted to remove Sumner as chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee.

Despite being stripped of chairmanship, Sumner would not be silenced. He delivered a speech condemning Grant’s use of the military to prop up “the usurper Baez.” This turned public opinion against annexation. Grant urged reconsideration throughout the remainder of his term, but the treaty was never presented to the Senate again.

Charles Sumner’s principled opposition to absorbing a people and a culture into the U.S. without their true consent stopped the U.S. annexation of San Domingo. But the expansionists continued pushing to annex Caribbean entities in later years. Puerto Rico was acquired in the Spanish-American War a generation later, and the Danish West Indies were finally acquired in 1917. As time went on, it became more important to expand “American exceptionalism” throughout the world than to respect the sovereignty of individuals and nations who may wish to determine their own political fates.

July 2, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Jul 1-7, 1863

Wednesday, July 1

In Pennsylvania, the Battle of Gettysburg began between General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and General George G. Meade’s Federal Army of the Potomac. Fighting erupted when the Federal vanguard under General John Buford arrived at the town. As General Richard Ewell’s Confederates advanced from the northwest, Buford held his ground and called on the rest of the Federal army to hurry and support him.

In Pennsylvania, the Battle of Gettysburg began between General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and General George G. Meade’s Federal Army of the Potomac. Fighting erupted when the Federal vanguard under General John Buford arrived at the town. As General Richard Ewell’s Confederates advanced from the northwest, Buford held his ground and called on the rest of the Federal army to hurry and support him.

Reinforcements gradually arrived on both sides, and the skirmish became a battle at several points outside Gettysburg. One of the Federals’ best corps commanders, General John Reynolds, was killed in action. The Federals slowly withdrew south of town to Cemetery Hill, where Robert E. Lee ordered Ewell to capture the position “if practicable.” Ewell decided not to attack, and a vital opportunity to seize the high ground and destroy the Federal army was lost. By day’s end, both sides had suffered terrible casualties, but Federal reinforcements were forming a nearly impregnable defense.

In Mississippi, the brutal Federal siege of Vicksburg was taking its toll on the Confederate troops and civilians in the city. Residents holed up in hillside caves to avoid artillery, and many were starving. Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, commanding the Western Theater, was unable to help the Confederates trapped in Vicksburg because General Ulysses S. Grant’s besieging Federal army was being constantly reinforced.

In Tennessee, General William S. Rosecrans’s Federal Army of the Cumberland captured Tullahoma without a fight after a brilliant campaign of maneuver against General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee. Because this campaign featured no major fighting, its success was overshadowed by Gettysburg and Vicksburg. Nevertheless, Bragg considered the loss of Tullahoma “a great disaster” as he withdrew to Chattanooga.

In Virginia, residents of Richmond were alarmed by a Federal expedition that came close to the capital city. In Missouri, a pro-Union state convention resolved to end slavery in the state by July 4, 1870. Skirmishing occurred in Kentucky and the Indian Territory.

Thursday, July 2

The Battle of Gettysburg continued, as Robert E. Lee ordered General James Longstreet to attack the Federal left at Cemetery Ridge and the Round Tops, while Richard Ewell attacked the Federal right at Culp’s and Cemetery Hills. The attacks were ineffective until Federals under General Daniel Sickles blundered by moving forward into a wheat field and creating a gap in the line. The Confederates captured several key points but were repulsed at Little Round Top by Colonel Joshua L. Chamberlain’s 20th Maine. The second day of fighting ended in brutal stalemate. That night, George G. Meade conferred with subordinates and decided to hold his ground. He hurried Federal reinforcements to the line’s center at Cemetery Ridge, guessing that since Lee had attacked both Federal flanks, he would try the center next.

In Mississippi, John C. Pemberton conferred with his commanders and agreed that Vicksburg must be surrendered to save the residents from starving. Pemberton contacted Ulysses S. Grant to discuss possible surrender terms, and a meeting between the two commanders was scheduled for tomorrow.

In Richmond, Confederate President Jefferson Davis authorized Vice President Alexander Stephens to “proceed as a military commissioner under flag of truce to Washington.” Stephens was to officially negotiate prisoner exchange, but he was also empowered to discuss a possible end to the war.

In Kentucky, Confederate General John Hunt Morgan began a raid to ease Federal pressure on Tennessee. General Braxton Bragg had approved Morgan’s Kentucky raid, but Bragg had not been informed that Morgan also planned to cross the Ohio River and invade the North. Skirmishing occurred in Louisiana, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Virginia.

Friday, July 3

The Battle of Gettysburg concluded. As George G. Meade had guessed, Robert E. Lee planned to attack the Federal center at Cemetery Ridge and split the line in two. Lee overruled James Longstreet’s objections, confident his troops would succeed. After one of the largest artillery fights in American history, Longstreet ordered his three divisions to advance in what became known as “Pickett’s Charge,” named for General George Pickett, one of the division commanders.

The Confederates marched through artillery and rifle fire, making it to the ridge where fierce hand-to-hand combat ensued. In what was later called the “Confederate high-water mark,” the charge was unsuccessful and the Federals were victorious. Lee refused pleas from his troops to try another charge, instead preparing defenses for a Federal counterattack that never came. This was the most terrible battle ever fought in North America, as nearly 50,000 men were killed, wounded, or missing over three days of fighting.

In Mississippi, a tense meeting occurred between John C. Pemberton and Ulysses S. Grant over possible surrender terms for the Confederates besieged in Vicksburg. Grant initially insisted that all captured Confederate soldiers be sent North as prisoners of war. But then he relented and offered to parole them if they pledged not to take up arms again. Pemberton agreed.

In Kentucky, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates skirmished as they advanced on Columbia. In New Orleans, the Federal commander banned all public gatherings except for church services without written permission; no more than three people were allowed to congregate at one place in the streets; and a 9 p.m. curfew was enacted to prevent rebellion against the Federal occupation forces. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee.

Saturday, July 4

John C. Pemberton formally surrendered Vicksburg to Ulysses S. Grant. This ended a Federal campaign that had lasted over a year; it left a once-proud Confederate stronghold in ruins with its residents starving and destitute. The remaining 29,000 Confederate soldiers marched out of Vicksburg at 10 a.m. and stacked their arms. Along with the men, the Federals also captured 172 cannon and 60,000 muskets. Grant’s Federals entered the city and began providing food to the starving civilians and soldiers.

The twin victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg sparked massive celebrations throughout the North, and 100-gun salutes were fired in most major cities. The fall of Vicksburg meant that the fall of Port Hudson was inevitable, thus opening the entire Mississippi River to Federal transport and commerce. This day marked the turning point of the war. From this point forward, the Confederacy could only rely on northern war weariness or foreign intervention for victory.

In Pennsylvania, Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia began returning to Virginia after its defeat at Gettysburg. President Lincoln announced “a great success to the cause of the Union” for the Army of the Potomac.

As the Confederate gunboat Torpedo carried Vice President Alexander Stephens down the James River to Hampton Roads, President Davis wrote to President Lincoln requesting that Stephens be allowed to negotiate with Federal authorities. However, having just won major victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Lincoln replied, “The request is inadmissible.”

In Kentucky, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates were temporarily repulsed at Tebb’s Bend on the Green River. In Arkansas, Confederates attacked Helena in a belated attempt to relieve Federal pressure on Vicksburg and Port Hudson. Skirmishing occurred in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Mississippi, Missouri, and the New Mexico Territory.

Sunday, July 5

Robert E. Lee’s Confederates moved toward Hagerstown, Maryland. George G. Meade’s Federals did not pursue, but there were minor cavalry skirmishes in Maryland and Pennsylvania.

In Mississippi, Federals under General William T. Sherman began moving toward the state capital at Jackson to confront the remaining Confederates in the state under General Joseph E. Johnston. Meanwhile, Ulysses S. Grant began paroling the captured Confederates at Vicksburg. In Kentucky, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates captured Lebanon and Bardstown. Skirmishing occurred in North Carolina and Tennessee.

Monday, July 6

Robert E. Lee’s Confederates continued withdrawing to Virginia, and George G. Meade’s Federals attempted no major pursuit. In Mississippi, William T. Sherman’s Federals continued advancing toward Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederates at Jackson. In Kentucky, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates captured Garnettsville as they continued moving north toward the Ohio River.

In Indiana, an anti-war group called the Knights of the Golden Circle seized guns and ammunition at the Huntington depot. Rear Admiral Samuel F. Du Pont was relieved as commander of the Federal South Atlantic Blockading Squadron due to his failed attack on Charleston, South Carolina.

Tuesday, July 7

In Tennessee, General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee established new positions at Chattanooga after losing most of the state to General William S. Rosecrans’s Federal Army of the Cumberland.

In Kentucky, John Hunt Morgan’s Confederates skirmished at Shepherdsville and Cummings’ Ferry as they approached the Ohio River. In the Arizona Territory, Colonel “Kit” Carson began an expedition against the Indians. In the North, the Conscription Act went into effect amidst much resentment. Skirmishing occurred in Missouri, Mississippi, and the Idaho Territory.

As Robert E. Lee’s Confederates continued withdrawing, Lee wrote to President Davis that the army would continue moving southward. Expressing concern about George G. Meade’s reluctance to pursue Lee, President Lincoln wrote to General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck, “Now, if General Meade can complete his work, so gloriously prosecuted thus far, by the literal or substantial destruction of Lee’s army, the rebellion will be over.”

June 26, 2013

The Missouri Compromise

An agreement among members of Congress only temporarily prevented hostilities between North and South.

The first major sectional conflict in American history had roots in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. The purchase doubled the size of America and prompted debate over how slavery should be regulated in the new territory. The debate intensified in 1818 when John Scott, a non-voting member of the House of Representatives, requested statehood for a portion of the Louisiana Purchase called the Missouri Territory.

A bill was submitted in the House authorizing Missouri to draft a state constitution and form a government in preparation for statehood. Slavery was not prohibited in the bill, which meant that it was implicitly permitted. The bill was not voted upon until early 1819.

Admitting Missouri to the Union threatened to disrupt the delicate balance of 11 slave and 11 free states represented in Congress. To prevent shifting the balance of power to the South, Congressman James Tallmadge of New York offered amendments to the Missouri bill prohibiting further slave importation into the territory and gradually emancipating the slaves already there.

The Missouri bill narrowly passed after fierce debate, largely because northerners outnumbered southerners in the House. However, the Senate contained an equal number of northerners and southerners, and since Missouri already allowed slavery, the Missouri bill was approved only after removing the Tallmadge amendments. When the revised bill returned to the House for reconciliation, it was rejected.

By the time the next Congress assembled in December 1819, the Missouri debate had become a national issue. In the House, another bill was submitted requesting statehood for Missouri, and Congressman John W. Taylor of New York submitted an amendment requiring slavery to be banned in Missouri for it to become a state. Meanwhile, a second bill had been introduced requesting statehood for the Maine Territory, which prohibited slavery.

As the Missouri bill was debated in the House, the Senate passed a bill granting statehood to Maine only if Missouri was also granted statehood without any restrictions on slavery. Maine’s fate now depended on Missouri’s. The Maine-Missouri bill stalled in the Senate until Kentucky Senator Henry Clay seized the opportunity for compromise.

Clay persuaded the debating factions to approve granting statehood to both Maine and Missouri. As a concession to slaveholding states, Missouri would have no slavery restrictions. Thus, one slave and one free state would be added to the Union, maintaining the balance between North and South in Congress. As a concession to the free states, slavery would be prohibited north of Missouri’s southern border, the 36-30 line, in the remainder of the Louisiana Territory.

The Senate passed the bill, but the House rejected the compromise because Maine’s potential statehood depended on Missouri’s fate. The House instead passed two separate bills granting statehood to both Maine and Missouri without conditions for either. The House retained the Senate amendment banning slavery north of the 36-30 line. The Senate approved the bills, and they were signed into law by President James Monroe in 1820.

The so-called Missouri Compromise pacified most slave and non-slave factions, but some were still dissatisfied. Former President Thomas Jefferson considered the compromise “as the knell of the Union… A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.” Sure enough, the Mexican-American War two decades later prompted a new sectional crisis.

While territory acquired from Mexico was not subject to the terms of the Missouri Compromise, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was. This created the Kansas and Nebraska Territories, and although both were north of the slavery boundary line, the act allowed the people in those territories to decide for themselves whether or not to permit slavery. This effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise.

Three years later, the Supreme Court officially declared that the Missouri Compromise was illegal in the controversial Dred Scott v. Sandford decision. The Court ruled that Congress had no authority to regulate slavery in the territories, which it had attempted to do under the compromise. This effectively opened all territory to slavery expansion, thus irreparably dividing North and South and effectively shoving the country toward civil war.

June 24, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Jun 24-30, 1863

Wednesday, June 24

In Tennessee, Federal General William S. Rosecrans wired Washington: “The army begins to move at 3 o’clock this morning.” After repeated urgings, Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland began moving out of Murfreesboro to confront General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee at Tullahoma. The Lincoln administration believed that pressing Rosecrans to attack would prevent Bragg from sending reinforcements to break the siege of Vicksburg.

In Mississippi, the situation inside Vicksburg was becoming critical. Federal shelling continued, and the residents suffered from lack of food and other supplies.

Federal General Joseph Hooker wired Washington asking for orders, stating that ”I don’t know whether I am standing on my head or feet.” Hooker’s Army of the Potomac was struggling to pursue General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia as it advanced northward into Pennsylvania.

Skirmishing occurred in Maryland, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

Thursday, June 25

Robert E. Lee dispatched his cavalry under General Jeb Stuart to block the movements of the Confederate forces from observation by the pursuing Federals. Stuart instead began a northern raid that handicapped Lee’s army in enemy territory.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis wrote to Braxton Bragg and General P.G.T. Beauregard at Charleston, South Carolina pleading for them to send reinforcements to Vicksburg. Davis stated that unless General Joseph E. Johnston was reinforced, “the Missi. (Mississippi River) will be lost.” Johnston’s Confederates tried harassing the Federals laying siege to Vicksburg, but were ineffective.

Friday, June 26

Joseph Hooker’s Federal forces finally completed crossing the Potomac River in pursuit of Robert E. Lee’s Confederates. It took Hooker eight days to cross the Potomac. The slow pace concerned Lincoln administration officials that Hooker may not be able to stop the Confederates’ northern invasion. Meanwhile, Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin called for 60,000 volunteers to serve three months to repel the invasion as a portion of Lee’s army under General Jubal Early reached Gettysburg.

Off the Maine coast, the Confederate schooner Archer was destroyed by Federal steamboats and tugboats. Commanded by Lieutenant Charles W. “Savez” Reed, Archer had caused panic in New England by capturing 21 ships, including the Federal revenue cutter Caleb Cushing off Portland, in 19 days. The Federals had dispatched 47 vessels to find and destroy Archer.

Skirmishing occurred in Pennsylvania, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Louisiana.

Saturday, June 27

Joseph Hooker submitted his resignation as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker was infuriated by General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck’s order to hold Harpers Ferry and Maryland Heights, believing it compromised his command. To Hooker’s surprise, President Lincoln accepted. Hooker was unaware that Lincoln had been waiting for a reason to relieve him of command ever since his May defeat at Chancellorsville.

In Pennsylvania, Jubal Early’s Confederates captured York.

Sunday, June 28

At 3 a.m., General George G. Meade, commander of Fifth Corps, was awakened and ordered to take command of the Army of the Potomac. Meade had no choice but to accept the tremendous responsibility and quickly formulate a strategy to stop Robert E. Lee’s northern invasion. By that afternoon, Meade developed a plan: “I must move toward the Susquehanna, keeping Washington and Baltimore well covered, and if the enemy is checked in his attempt to cross the Susquehanna, or if he turns toward Baltimore, give him battle.” President Lincoln approved Meade’s strategy.

When Lee learned that Meade had replaced Hooker, he abandoned plans to attack Harrisburg. Instead, Lee turned back south and began concentrating his Confederates near Gettysburg and Cashtown. At York, Jubal Early’s Confederates seized shoes, clothing, rations, and $28,600. In Virginia, Confederate cavalry under Jeb Stuart skirmished near Fairfax Court House.

In Tennessee, William Rosecrans’s Federals occupied Manchester as part of their Tullahoma Campaign. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Louisiana.

Monday, June 29

George G. Meade’s Federals moved quickly through Maryland, and General John Buford’s Federal cavalry reached Gettysburg. In Tennessee, heavy skirmishing occurred as part of the Tullahoma Campaign. Other skirmishing occurred in Louisiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, and West Virginia.

Tuesday, June 30

In Tennessee, Confederates began evacuating Tullahoma as William S. Rosecrans’s Federals advanced on the town. In Pennsylvania, Robert E. Lee’s Confederates were converging on Gettysburg. President Lincoln rejected panicked pleas to reinstate George B. McClellan to army command during this crucial time. Skirmishing occurred in Missouri and Louisiana.

Primary source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)