Walter Coffey's Blog, page 181

November 14, 2013

The Liberal Republican Movement

A fledgling 19th century organization has served as the foundation for conservatism in American politics today.

Ulysses S. Grant was preparing to run for a second term as president in 1872. He had been strongly supported by the Republican Party in his first presidential campaign four years earlier, but by this time, many Republicans had become disillusioned by the rampant corruption taking place within his administration. These detractors formed a new group called the Liberal Republican Party.

The party derived its name from the classical definition of “liberal,” which in 19th century terms meant smaller, more limited government. The Liberals supported reducing the size and scope of the federal government, lowering taxes, embracing free market economic principles, and battling corruption.

The Liberal Republican Party included Democrats and Republicans, and even holdovers from the defunct Whig Party. They all had different reasons for joining the party, but they generally agreed that government corruption must be stopped and there must be a return to the nation’s founding principles of limited national government and increased local self governance.

The movement was predicated on the notion that anyone could succeed in America through hard work, regardless of their race, gender, or economic status. The Liberals opposed government favoring special interests over the people, but they also opposed people who demanded special favors from the government. And they opposed people using the government to redistribute wealth rather than earn it themselves.

Liberal Republican campaign poster

At the 1872 national convention, party leader Carl Schurz said, “We want the overthrow of a pernicious system; we want the eradication of flagrant abuses; we want the infusion of a loftier spirit into our political organism; we want a Government which the best people of this country will be proud of.” The idea that this new party would be above the muck of politics was immediately compromised when a backroom deal was made to nominate Horace Greeley for president.

Greeley was the editor of the influential New York Tribune, and although he shared the Liberals’ zeal for reform, he didn’t share many of the same principles as his party. For instance, Greeley supported high tariffs (i.e., taxes) on imported goods while the Liberals favored lowering taxes. Greeley had also supported alcohol prohibition and communism for a time, which directly conflicted with the Liberals’ devotion to individual liberty. In choosing Greeley, the Liberals compromised their principles in the hopes that he was famous enough to defeat Grant in the presidential election.

E.L. Godkin, editor of The Nation, wrote that it was “impossible for anyone to speak of ‘reform’… without causing shouts of laughter… We suppose that a greater degree of incredulity and disappointment has not been felt… since the news of the first battle of Bull Run.” Disappointed by Greeley’s nomination, Schurz asked him to withdraw. When Greeley refused, Schurz and other reformers nominated a different candidate for president instead.

At the time, the South was under military occupation in the aftermath of the Civil War. The Liberals alienated the newly freed slaves by calling for an end to the occupation and amnesty for ex-Confederates. Liberals also alienated farmers and laborers by calling for a gold-based economy, which would make paper money that they used to survive harder to come by. Liberals alienated business leaders and industrialists as well by favoring an end to government subsidies and land grants.

When the Democrats held their nominating convention, they feared that the Liberals would split their vote and enable Grant’s reelection. So they also nominated Greeley for president. This proved a major blunder because Greeley had become famous as a newspaper editor by savaging the Democratic Party for years. Having espoused so many opinions (many of them radical) in print, Greeley’s opponents had endless material to use against him. The campaign was so brutal that Greeley had to commit his wife to an institution from the stress, and then Greeley himself died less than a month after the election.

As the Liberals learned, reform is a noble cause but not necessarily a popular one; Grant was easily reelected. Nevertheless, America slowly began embracing Liberal ideas as the century progressed. More Americans began expressing opposition to government corrupted by special interests, instead supporting a more limited government that operated within constitutional restraints. The notion that anyone could succeed in America helped reunite North and South.

The Liberal Republican agenda of limited government, low taxes, free markets, and individual freedom was completely adopted by the conservative movement, spearheaded by Ronald Reagan’s run for president in 1980. Today, these are the general principles of the Tea Party Movement and other conservative/libertarian groups opposed to excessive government infringement on the rights of the states and the people.

November 12, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Nov 11-17, 1863

Wednesday, November 11

Controversial Major General Benjamin F. Butler returned to active duty by assuming command of the Federal Department of Virginia and North Carolina. Butler quickly ordered the arrest of anyone demonstrating disloyalty through “opprobrious and threatening language.”

Confederate President Jefferson Davis became increasingly concerned that Federal troops were preparing to break through General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee besieging Chattanooga. Davis told Bragg that he should ”not allow the enemy to get up all his reinforcements before striking him, if it can be avoided…”

Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and the Indian Territory.

Thursday, November 12

Washington’s social event of the year occurred with Kate Chase, daughter of Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, marrying Senator William Sprague of Rhode Island. President Lincoln was among the dignitaries attending the wedding.

Renewed Federal shelling of Fort Sumter began in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. Pro-Union officials met in Little Rock, Arkansas to discuss restoring the state to the Union. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and the Indian Territory.

Friday, November 13

The Federal bombardment of Fort Sumter continued. Federal expeditions began in Charleston, West Virginia and Cape Fear River, North Carolina. Federal troops skirmished with Indians near the Trinity River in California. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Tennessee, and Arkansas.

Saturday, November 14

The Federal bombardment of Fort Sumter continued. Brigadier General Nathan Bedford Forrest was assigned to Federal-controlled western Tennessee. In response to North Carolina farmers threatening to resist Confederate taxation, the Davis administration announced that force and confiscation would be used to collect taxes if necessary.

Federal expeditions began from Martinsburg, West Virginia; Maysville, Alabama; and Helena, Arkansas. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia and Tennessee.

Sunday, November 15

Four divisions of the Federal Army of the Tennessee, commanded by General William T. Sherman, arrived at Bridgeport, Alabama to reinforce the besieged Federals in Chattanooga. Sherman conferred with General Ulysses S. Grant, commanding the besieged forces, in Chattanooga.

Federal authorities in western Tennessee and northern Mississippi increased restrictions on trading with the enemy and consorting with Confederate guerrillas for profit. Administration guidelines were largely ignored in this region of Federal occupation, which was riddled with corruption and mismanagement.

The Federal bombardment of Fort Sumter slowed, with 2,328 rounds fired since November 12. Federal cavalry operations were conducted in Virginia and West Virginia. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee, South Carolina, and Arkansas.

Monday, November 16

Confederates under General James Longstreet approached Knoxville in eastern Tennessee. Longstreet had detached from Braxton Bragg’s Confederates at Chattanooga to attack General Ambrose Burnside’s Federal Army of the Ohio occupying the city. Burnside planned to meet Longstreet south of town and gradually withdraw, thus drawing Longstreet further from Chattanooga.

After sharp skirmishing, Burnside withdrew as planned and Longstreet failed to cut Burnside’s retreat line at Campbell’s Station. Burnside reported to President Abraham Lincoln that Longstreet had crossed the Tennessee and the Federals were retiring to Knoxville.

General Nathaniel Banks’s Federals occupied Corpus Christi, Texas in their campaign to conquer eastern Texas. Federals fired 602 rounds into Fort Sumter. Federal ships attacked the batteries on Sullivan’s Island, with U.S.S. Lehigh badly damaged before escaping.

A Federal expedition began from Vidalia, Louisiana. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, West Virginia, and Tennessee.

Tuesday, November 17

James Longstreet began a Confederate siege of Knoxville. The Federal bombardment of Fort Sumter continued. In Texas, Federals captured a Confederate battery at Aransas Pass near Corpus Christi.

Federal expeditions began from New Creek, West Virginia and Houston, Missouri. Skirmishing occurred in Mississippi and California.

Primary Source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

November 10, 2013

The Wounded Knee Massacre

The massacre of Indian men, women, and children in December 1890 ended any significant resistance to U.S. authority and relegated Native American tribes to permanent government dependency.

By the 1890s, most Sioux Indians on the Great Plains had been rounded up and placed on reservations. Desperate to free themselves from U.S. control, the Sioux embraced a new ritual called the Ghost Dance. The Sioux believed that practicing the Ghost Dance would resurrect their ancestors, replenish the buffalo, and wipe the white man off the earth.

Aftermath of the Wounded Knee Massacre

U.S. officials became concerned as the Ghost Dance ritual spread among the reservations. In response, they attempted to arrest Chief Sitting Bull at the Standing Rock Reservation. Sitting Bull was accused of trying to incite an uprising by encouraging the Sioux to practice the Ghost Dance. When Indians resisted the authorities at Standing Rock, a gunfight erupted and Sitting Bull was killed.

The Sioux were so confident that the Ghost Dance would deliver them from U.S. rule that they did not try to avenge Sitting Bull’s death. Instead, many of them fled Standing Rock, with about 100 Hunkpapa Sioux going to the Minneconjou Sioux camp of Chief Big Foot, Sitting Bull’s half-brother. Big Foot was one of the last Indian chiefs that had not yet submitted to U.S. authority.

The U.S. War Department issued a warrant for Big Foot’s arrest as one of the “fomenters of disturbances.” When Big Foot was informed that Sitting Bull had been killed, he led his band toward the camp of Chief Red Cloud on the Pine Ridge Reservation. It was hoped that Red Cloud could negotiate a peace between the Indians and U.S. authorities. Big Foot’s band included 120 men and 230 women and children; most of them had lost relatives in prior conflicts with U.S. forces.

On the way to Pine Ridge, Big Foot was stopped by a portion of the 7th U.S. Cavalry, the same regiment that had been decimated at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. Led by Major Samuel Whitside, the U.S. troopers placed Big Foot in an ambulance because he was suffering from pneumonia and escorted the Indian band to Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota. Because they arrived at the encampment late in the day, Whitside decided to wait until the next day to disarm the Indians.

That night, the rest of the 7th Cavalry arrived with their commander, Colonel James W. Forsyth. Forsyth informed his men that the Indians were to be taken to the Union Pacific Railroad the next day and transported to a military prison in Omaha, Nebraska. After stationing sentinels and four Hotchkiss guns to prevent escape, Forsyth and his men drank to celebrate Big Foot’s capture. Meanwhile, fearful rumors spread through the Indian camp that the U.S. troopers would avenge their defeat at Little Bighorn.

The next morning, the Indians were issued breakfast rations and informed that they would be taken to Pine Ridge. The Indians were then notified that they would be disarmed. They stacked their arms for collection, but the troopers also searched tepees and seized axes, knives, and other items that could be used as weapons. The troopers then searched the Indians themselves. Two rifles were found, and when an Indian objected to surrendering his weapon because he had paid a high price for it, the gun discharged and the troopers opened fire.

The Indians tried fleeing, but the Hotchkiss guns shredded the camp. When the firing stopped, it was reported that 84 men, 44 women, and 18 children were killed, including Big Foot. U.S. forces suffered 25 dead and 39 wounded, but since few Indians had access to weapons, most of the U.S. casualties were due to friendly fire. Because of an approaching blizzard, the Indian corpses were left where they lay until a civilian detail came to bury them in a mass grave. Of the 350 Indians who had been detained at Wounded Knee, only four men and 47 women reached Pine Ridge.

A band of Sioux attacked the 7th Cavalry the day after the incident, but the 7th was rescued by the black troopers of the 9th Cavalry, and the Indians were too hungry and demoralized to resist any further. Although General Nelson A. Miles described the incident as a “massacre” to the commissioner of Indian Affairs, the U.S. government awarded 20 medals of honor for the action. The Indians were finally dispersed among various reservations where they lived in poverty for generations.

Black Elk, an Oglala Sioux medicine man who was injured at Wounded Knee, recalled the tragic incident: “I did not know then how much was ended. When I look back now from this high hill of my old age, I can still see the butchered women and children lying heaped and scattered all along the crooked gulch as plain as when I saw them with eyes still young. And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream… the nation’s hoop is broken and scattered. There is no center any longer, and the sacred tree is dead.”

Primary Sources:

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown

A Patriot’s History of the United States by Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen

A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn

November 8, 2013

Buck v. Bell: Sterilized by the State

The Supreme Court established a dangerous precedent by ruling that the government could involuntarily sterilize people “for the protection and health of the state.”

The Virginia legislature passed a law in 1924 permitting the state to forcibly sterilize anybody considered unfit to reproduce. This law was based on the work of Harry Laughlin, a leading eugenicist who worked with various state legislatures to enact measures that would enable compulsory sterilization by removing doctors’ fears that their patients would sue them.

Carrie Buck

Dr. James H. Bell, superintendent of the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble Minded, was granted a request by the Board of Directors to sterilize 18-year old patient Carrie Buck, who was considered mentally retarded. Buck already had a daughter that was also deemed retarded, as was Buck’s mother.

It was alleged that Buck posed a genetic threat to society if she was permitted to continue reproducing. Buck had been pronounced “incorrigible” for immorally having a child out of wedlock. But it was later revealed that Buck’s cousin had raped her, and Buck’s family had her committed to the asylum to protect the family name.

Laughlin declared that sterilizing Buck would be “a force for the mitigation of race degeneracy.” He based this dubious claim on a nurse who stated, “These people (the Bucks) belong to the shiftless, ignorant, and worthless class of anti-social whites of the South.”

Buck’s guardian tried stopping the procedure, but the Circuit Court of Amherst County and Virginia’s Supreme Court of Appeals ruled that Buck could be sterilized. The case was then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, where Buck’s counsel argued that sterilizing a person against her will under any circumstances violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The Court disagreed.

Disregarding the natural right to life, the Court ruled that the state had the power to sterilize people against their will. Only one justice dissented. The Court’s opinion was written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who wrote that since Buck would be “the probable potential parent of a socially inadequate offspring, likewise affected… she may be sexually sterilized.”

Holmes cited a Massachusetts law requiring the vaccination of children as a precedent, writing that “the principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes.” To Holmes, sterilization was simply a public health measure serving the “greater good” at the expense of personal freedom.

Holmes’s alarming opinion foreshadowed views that would soon be espoused by the rising Nazi Party in Germany. He stated, “(i)t is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind.” Holmes ended with the infamous statement, “(t)hree generations of imbeciles are enough.”

Representing Buck was Irving Whitehead, who had served on the asylum’s Board of Directors and even approved the initial request to sterilize Buck. Critics accused Whitehead of conflict of interest, and even of deliberately botching the case in an effort to maintain the family name. Buck was sterilized as ordered, and she lived as a domestic worker until 1983.

The Court ruling reflected the Progressive view that humans could (and should) modify or correct anything that the state defines as imperfect, and it led to the passage of sterilization laws in dozens of states. The government’s power to deny life to any citizen considered defective is a flagrant violation of the natural right to life, a fundamental principle upon which this country was founded.

Primary Sources:

Theodore and Woodrow by Andrew P. Napolitano

Liberal Fascism by Jonah Goldberg

A Patriot’s History of the United States by Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen

November 6, 2013

Support the AAFMAA!

November 5, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Nov 4-10, 1863

Wednesday, November 4

Confederate General Braxton Bragg weakened his Army of Tennessee by sending a corps under General James Longstreet to Knoxville to attack General Ambrose Burnside’s Federal Army of the Ohio. Longstreet strongly opposed this order because it both weakened Bragg and pitted Longstreet’s small force against Burnside’s superior army. But because Longstreet had complained about Bragg’s leadership, President Jefferson Davis allowed Bragg to detach him.

President Davis continued his southern tour by visiting James Island and the forts and batteries at Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Missouri, and the Arizona Territory.

Thursday, November 5

The Federal bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor was reduced. John S. Mosby’s Confederate raiders operated in northern Virginia. Three Confederate blockade runners were captured near the mouth of the Rio Grande River, and another three were seized off Florida and South Carolina.

President Abraham Lincoln wrote to General Nathaniel Banks, Federal commander of the Army of the Gulf, expressing disappointment that a civil government was not yet installed in Louisiana. Lincoln urged Banks to “lose no more time,” emphasizing that the government must “be for and not against” the slaves “on the question of their permanent freedom.”

Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, West Virginia, Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Missouri.

Friday, November 6

Brigadier General William W. Averell’s Federals cleared Confederates from Droop Mountain in West Virginia. This enabled the Federals to operate more freely in the region and destroy important Confederate railroad links between Virginia and the Southwest.

President Davis stopped at Wilmington, North Carolina on his return to Richmond. Davis said he recognized the importance of the harbor there, since it was the only port truly open for Confederate trade. Davis received a report from the Trans-Mississippi that stated, ”The morale of the army is good and the feelings (sic) of the people is better than it was” in Arkansas, now separated from the rest of the Confederacy.

In the eastern Texas campaign, Nathaniel Banks’s Federals occupied areas around Point Isabel and Brownsville, Texas, near the Mexican border. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia and Tennessee.

Saturday, November 7

The Federal Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia continued movements in northern Virginia. Major General George G. Meade’s Federals fought heavy skirmishes with General Robert E. Lee’s withdrawing Confederates at Rappahannock Station and Kelly’s Ford. As Meade pushed across the Rappahannock River, Lee withdrew to the Rapidan River.

William W. Averell linked with A.N. Duffie’s Federals and captured Lewisburg, West Virginia. A Federal expedition began from Fayetteville to Frog Bayou, Arkansas. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia.

Sunday, November 8

In northern Virginia, the Federal advance across the Rappahannock continued with skirmishing at various points. The Federal expedition in West Virginia skirmished at Second Creek. Skirmishing occurred in Louisiana.

Major General John C. Breckinridge replaced Lieutenant General D.H. Hill as commander of Second Corps in Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee. This was another attempt to end the animosity between Bragg and his subordinates.

Monday, November 9

In Virginia, a Federal expedition began at Williamsburg, east of Richmond. President Davis returned to Richmond amidst an early snowstorm.

President Lincoln wired George G. Meade concerning his army’s recent movements: “Well done.” Lincoln then attended the drama The Marble Heart featuring the famous actor John Wilkes Booth. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, North Carolina, Louisiana, and the Indian Territory.

Tuesday, November 10

As of today, Fort Sumter had sustained 1,753 shells in its walls over the past three days. Federal expeditions began in Arkansas and Missouri to clear out Confederate guerrillas. A Federal expedition began from Skipwith’s Landing, Mississippi.

Primary Source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

October 30, 2013

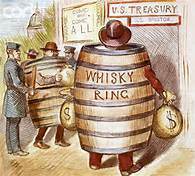

The Whiskey Ring

A major political scandal erupted within the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant when it was revealed that federal tax collectors were colluding with whiskey distillers to avoid paying taxes.

Cartoon by Thomas Nast

Whiskey taxes had been sharply increased after the Civil War, prompting distillers to bribe tax collectors to avoid paying such exorbitant sums. General John McDonald, supervisor of internal revenue in St. Louis and personal friend of President Grant, led a conspiracy to accept such bribes. The conspiracy involved distillers in not only St. Louis, but also Chicago, Peoria, Milwaukee, Cincinnati, and New Orleans.

When reformer Benjamin Bristow became Treasury secretary, he worked with Treasury Solicitor Bluford Wilson to hire a reporter to investigate the rumors. The reporter followed the trail leading to McDonald as the plot’s central figure in St. Louis.

It was reported that distillers and tax collectors had been defrauding the federal government of taxes, and some of the funds that should have gone toward tax payments were used to finance Republican Party campaigns. McDonald was summoned to Washington, where he admitted involvement to Bristow. Bristow and Wilson submitted the evidence to Grant.

Bristow then ordered raids on other federal tax offices. The raid plans were so secret that neither Grant nor his attorney general was notified beforehand. Special investigators seized records and arrested about 350 distillers and government officials.

It was discovered that whiskey distillers, storage managers, distributors and others had been bribing tax collectors to ignore various irregularities in whiskey manufacturing since at least 1870. Over $3 million in federal taxes were stolen in the locales where the conspiracy operated. It was estimated that between 12 and 15 million gallons of whiskey had gone untaxed in the past five years.

As the scheme progressed, suspicions had been aroused when the participants began appearing increasingly prosperous, despite having such low-paying jobs. Grant and his former Treasury secretary had ignored warnings about a conspiracy, and when an investigation was finally ordered, the appointed investigators were bribed to divulge nothing. Even the Treasury’s chief clerk was a participant.

Despite the evidence, Grant resisted prosecuting McDonald because of the friendship between McDonald and General Orville E. Babcock, Grant’s personal secretary. McDonald had bestowed lavish gifts on both Grant and Babcock in the past. To Grant’s dismay, evidence soon surfaced that Babcock had been involved in the ring as well.

Bristow appointed John B. Henderson as a special prosecutor to bring those involved in the ring to justice. When Henderson obtained a grand jury indictment against Babcock, Grant fired Henderson for attacking his secretary. The press blasted Grant for saving Babcock from certain conviction. Henderson’s removal crippled the prosecution and greatly aided the conspirators.

Being a general, Babcock demanded a trial before a military tribunal, which would more likely acquit him than a civil court. Grant’s cabinet reluctantly agreed, and Grant appointed three friendly generals to preside over the case. Declaring, “Let no guilty man escape,” Grant directed the attorney general to secretly order no immunity for suspects who informed on others. The press revealed the secret order and condemned it because it meant there would be no reward for testifying against Babcock.

Igniting even more criticism was Grant’s dismissal of special investigator Charles S. Bell. Bell had been hired to prove Grant’s assertion that his political enemies were trying to embarrass him by attacking Babcock. Bell instead uncovered even more damaging evidence against Babcock, prompting Grant to fire him.

Grant planned to travel to St. Louis to personally testify on Babcock’s behalf, but Secretary of State Hamilton Fish persuaded him to relent. Grant instead endorsed a deposition vouching for Babcock’s character and calling the charges against him baseless. The endorsement took place at the White House in the presence of the prosecuting and defense attorneys, and was signed by the chief justice of the Supreme Court.

Not surprisingly, Babcock was acquitted. He was also given $10,000 from admirers. The alleged ringleader in St. Louis, McDonald, was sentenced to three and a half years in prison and fined $5,000. In all, 238 people were indicted and tried. Of the 238, 110 were convicted, and over $3 million in taxes were recovered.

There was no evidence that Grant was personally involved. However, he permitted Babcock to return to work at the White House until pressure from his cabinet and the public finally forced Grant to reassign him. Bristow, who had broken the Whiskey Ring, eventually resigned due to Grant’s resentment over his persecution of Babcock. Grant’s intense loyalty to his secretary led many to question his ethics. And Grant’s opposition to those seeking to punish corruptionists like Babcock cast great doubts on the president’s credibility.

The Whiskey Ring was the most infamous of all the scandals within the Grant administration, and the public was shocked by the enormity of the crimes. This, unlike prior scandals, was directly linked to the White House, which demonstrated the vast corruption involved in the growing alliance between government and business.

October 29, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Oct 28-Nov 3, 1863

Wednesday, October 28

In the evening, General James Longstreet’s Confederate corps attacked Federal forces in Lookout Valley, Tennessee to stop the Federals from breaking the Confederate siege of Chattanooga. The Confederates withdrew after intense fighting, and the cracker line supplying the besieged Federals remained intact.

Regarding the volatile situation in Missouri, President Abraham Lincoln wrote to General John A. Schofield, commander of the Federal military district, ”Prevent violence from whatever quarter; and see that the soldiers themselves, do no wrong.”

Federal cavalry occupied Arkadelphia, Arkansas, south of Little Rock. In Charleston Harbor, Federal forces fired 628 artillery rounds into Fort Sumter. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee.

Thursday, October 29

Confederate President Jefferson Davis diffused a longstanding problem between General Braxton Bragg, commander of the Army of Tennessee, and cavalry commander Nathan Bedford Forrest by giving Forrest an independent command. Forrest had threatened to kill Bragg after the Battle of Chickamauga. From Atlanta, Davis expressed satisfaction that he had successfully urged “harmonious co-operation,” but this was short-lived.

One of the heaviest Federal bombardments of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor began. A Federal expedition began from Winchester to Fayetteville, Tennessee. Skirmishing occurred in Alabama and Missouri.

Friday, October 30

The intense Federal bombardment of Fort Sumter continued. A pro-Union delegation assembled at Fort Smith, Arkansas and elected a representative to the U.S. Congress. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, Louisiana, and the Indian Territory.

Saturday, October 31

Fort Sumter fell under heavy Federal bombardment once more. Over the last three days, 2,961 rounds of artillery were fired into Sumter, making this the fort’s heaviest punishment of the war. By this time, Sumter held more symbolic than military significance, yet the Confederate defenders continued holding firm. Skirmishing occurred in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

Sunday, November 1

General Ulysses S. Grant’s Federal cracker line became fully operational. This broke the Confederate siege of Chattanooga by delivering supplies to Federals in the city via Brown’s Ferry on the Tennessee River. President Davis began his return to Richmond after his southern tour. At Savannah, Davis wrote to Braxton Bragg expressing disappointment about Grant’s new supply line.

Federal forces fired 786 artillery rounds into Fort Sumter. General William B. Franklin’s Federals retired from Opelousas to New Iberia, Louisiana in a sputtering effort to conquer eastern Texas. Federal cavalry expeditions began in West Virginia. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee and Mississippi.

Monday, November 2

President Lincoln was invited to attend the dedication of the new Gettysburg National Cemetery on November 19 and offer “a few appropriate remarks.” Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin had approved the purchase of 17 acres of the battlefield to create a burial site for the fallen Federal soldiers. Although the invitation came less than three weeks before the dedication, Lincoln accepted.

Lincoln expressed concern that violence may occur during upcoming state elections. In a letter about press criticism, Lincoln wrote, “I have endured a great deal of ridicule without much malice; and have received a great deal of kindness, not quite free from ridicule. I am used to it.”

Federals launched 793 artillery rounds into Fort Sumter. President Davis visited Charleston and noted that the city “was now singled out as a particular point of hatred to the Yankees,” but he “did not believe Charleston would ever be taken.” If Charleston fell, Davis urged that the “whole be left one mass of rubbish.” The sound of booming Federal cannon was heard during Davis’s speech.

As William B. Franklin’s Federals withdrew in Louisiana, Federals under General Nathaniel Banks moved west and landed at Brazos Santiago where the Rio Grande River flows into the Gulf of Mexico. This began another Federal campaign to stop Mexican trade with the Confederacy by seizing control of the Rio Grande River and the Texas coastline. Banks had been ordered to attack eastern Texas from the Red River, but political considerations led to Banks choosing this presumably safer route.

Brigadier General John McNeil became commander of the Federal District of the Frontier. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas.

Tuesday, November 3

With Federal troops in Chattanooga receiving full rations once more via the cracker line, President Lincoln informed Secretary of State William H. Seward at Auburn, New York that Ulysses S. Grant’s dispatches “show all quiet and doing well.”

Federals fired 661 artillery rounds into Fort Sumter. Strong skirmishing occurred at Bayou Bourbeau and Carrion Crow Bayou, Louisiana. The Federals were repulsed, but their reinforcements helped them regain their positions. Confederate cavalry operated against the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Tennessee, and Mississippi.

Primary Source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press Inc., 1971)

October 25, 2013

The Water Cure

The U.S. practice of waterboarding (i.e., simulating drowning) suspected terrorists to extract information is not a new tactic. It began over a century ago and became prevalent when U.S. forces were fighting to deny independence to the Philippines.

In the 1890s, citizens of the Philippines rebelled against ruling Spain in their quest for independence. When the U.S. declared war on Spain in 1898, Filipinos saw the U.S. forces as their liberators. But when Spain was defeated, the U.S. seized control of the Philippines. Realizing that they would not be granted independence, the Filipinos began rebelling against U.S. rule in what became an undeclared war lasting over four years.

During this conflict, U.S. troops regularly used what was called the “water cure” to extract information from captured soldiers and civilians. The term “water cure” was actually derived from a therapeutic procedure that was popular in the late 1800s. In warfare, applying the water cure meant forcing prisoners to drink large amounts of water while lying down. This distended their stomachs and sometimes led to death if they refused to talk.

Use of this technique was even featured on the cover of Life magazine in 1902. The cartoon depicting a Filipino soldier receiving the water cure while Europeans observed contained the caption: “Chorus in background: Those pious Yankees can’t throw stones at us anymore.” This referenced U.S. criticisms of barbaric acts committed by European countries in past wars.

Use of this technique was even featured on the cover of Life magazine in 1902. The cartoon depicting a Filipino soldier receiving the water cure while Europeans observed contained the caption: “Chorus in background: Those pious Yankees can’t throw stones at us anymore.” This referenced U.S. criticisms of barbaric acts committed by European countries in past wars.

President Theodore Roosevelt contended, “Nobody was seriously damaged (by the water cure) whereas the Filipinos had inflicted incredible tortures on our people… Nevertheless, torture is not a thing that we can tolerate.” However, one soldier reported that “he helped to administer the water cure to one hundred and sixty natives, all but twenty-six of whom died.”

A Senate committee chaired by Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts held hearings pertaining to the Philippine conflict in general and use of the water cure in particular. The committee was dominated by senators who supported maintaining U.S. authority in the Philippines. In 1902, the committee issued a 3,000-page report after holding secret hearings on alleged war crimes.

William Howard Taft, military governor of the Philippines (and future U.S. president and chief justice), admitted in his testimony that “the torturing of natives by so-called water-cure and other methods” were used “on some occasions to extract information… There are some amusing instances of Filipinos who came in and said they would not say anything unless tortured; that they must have an excuse for what they proposed to say.”

David P. Barrows, a Philippine school director who supported U.S. control of the islands, claimed that alleged torture via the water cure “injured no one.” He also claimed that the concentration camps where U.S. troops were forcing Filipino civilians to live actually improved the quality of life in the Philippines. Barrows said that Filipinos went to live in the camps on “their own volition… (they) are pleased with it, because they are permitted to live an easier life—much easier than at home.”

Opponents of the U.S. occupation were not allowed to testify. Also barred from testifying was Major Cornelius Gardener, the Philippine provincial governor of Trabayas. Gardener claimed that the residents of the province initially supported the U.S. occupation, but “the torturing of natives by so-called water cure and other methods… is in my opinion sowing the seeds for a perpetual revolution against us hereafter whenever a good opportunity offers… the American sentiment is decreasing and we are daily making permanent enemies.”

Nevertheless, many witnesses who testified claimed that torture was necessary because of the Filipinos’ “inability to appreciate human kindness.” Others testified that the water cure was useful in getting Filipino rebels to confess to applying horrific torture of their own on captured U.S. soldiers. A U.S. sergeant alleged that even the Presidente of Igbaras in the province of Iloilo had been given the water cure for refusing to tell whether Filipino rebels had been alerted of the U.S. presence in the town.

According to a contributor from Harper’s Weekly, “A choice of cruelties is the best that has been offered in the Philippines. It is not so certain that we at home can afford to shudder at the water cure unless we disown the whole job, and if we do disown the whole job we cannot put the responsibility for it on the army. The army has obeyed orders. It was sent to the Philippines to subdue the Filipinos, and it seems to have made remarkable progress.”

The hearings resulted in no definitive course of action. Senator Albert Beveridge of Indiana, a supporter of the U.S. occupation, published a separate report commending the U.S. military for acting humanely and denouncing opponents of the U.S. occupation as unpatriotic defamers. Thus, use of the water cure would continue until the rebellion was finally suppressed. The Philippines were not granted independence until 1946, nearly a half century later.

Primary sources:

Theodore and Woodrow by Andrew Napolitano (Kindle version), Chapter 13

The New York Times, various issues between March 11 and May 20, 1902

October 22, 2013

The Civil War This Week: Oct 21-27, 1863

Wednesday, October 21

At Stevenson, Alabama, Major General Ulysses S. Grant conferred with General William S. Rosecrans, who had just been relieved as commander of the Army of the Cumberland under siege in Chattanooga. Grant then proceeded to Chattanooga, which was difficult to reach due to the Confederate siege, harsh mountain roads, and the fact that Grant was on crutches after falling from his horse.

Federals under Major General William B. Franklin occupied Opelousas, Louisiana after fighting there and at Barre’s Landing in their campaign to capture eastern Texas. A Federal expedition began from Charleston, West Virginia. Skirmishing occurred in Alabama, Tennessee, and Missouri.

Thursday, October 22

Ulysses S. Grant continued trying to get to Chattanooga via the treacherous mountain roads. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Missouri.

Friday, October 23

Confederate President Jefferson Davis transferred General Leonidas Polk to Mississippi. Polk had been a corps commander in General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, but had been relieved by Bragg for allegedly delaying an attack at Chickamauga last month.

Ulysses S. Grant arrived in Chattanooga and met with General George H. Thomas, commander of the besieged Army of the Cumberland. It took Grant three days to get into Chattanooga. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia and North Carolina.

Saturday, October 24

In Chattanooga, Ulysses S. Grant conducted inspections and ordered the opening of a new supply line at Brown’s Ferry on the Tennessee River. This would enable supplies to be transported from Alabama rather than through the difficult mountain passes.

President Abraham Lincoln instructed Federal General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck that “with all possible expedition the Army of the Potomac get ready to attack (Confederate General Robert E.) Lee…” General George G. Meade, commanding the Army of the Potomac, replied that he would “make every preparation with the utmost expedition to advance…”

Major General William T. Sherman replaced Grant as commander of the Federal Army of the Tennessee. General Jo Shelby’s Confederate raiders fought in Missouri and Arkansas as Shelby’s Missouri raid drew to a close. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Alabama, and Louisiana.

Sunday, October 25

General John S. Marmaduke’s Confederates attacked Pine Bluff, Arkansas after his demand for its surrender was refused. Marmaduke eventually withdrew after partially occupying the town. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia and Tennessee.

Monday, October 26

General Joseph Hooker’s Federals crossed the Tennessee River at Bridgeport, Alabama and cleared the area in preparation for opening the new supply line to the besieged Federals in Chattanooga.

Jo Shelby’s Confederates fought in Arkansas after returning from the Missouri raid. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, and Missouri.

Tuesday, October 27

Joseph Hooker’s Federals advanced to the western foot of Lookout Mountain, and a pontoon bridge was erected across the Tennessee River below Chattanooga at Brown’s Ferry. Within days, supplies began reaching Federals in Chattanooga through what became known as the “cracker line,” and the siege of Chattanooga was broken.

Federal naval forces began another bombardment of Fort Sumter and other defenses in Charleston Harbor. Major General Nathaniel Banks, commander of the Federal Army of the Gulf, began a third campaign to gain a foothold in eastern Texas by advancing toward the Rio Grande River and the Texas coast. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, North Carolina, West Virginia, Tennessee, Alabama, and Arkansas.

Primary source: The Civil War Day by Day by E.B. Long and Barbara Long (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)