Ken Lizzi's Blog, page 6

November 3, 2024

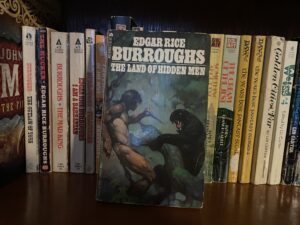

Finding ERB’s The Land of Hidden Men

Tarzan and John Carter are deservedly famous. But I have extracted a perhaps unexpected amount of enjoyment from several of Edgar Rice Burrough’s less well known books, such as The Mucker, I Am A Barbarian, The Outlaw of Torn, and The Mad King. Now add to that The Land of Hidden Men.

The Land of Hidden Men was originally titled Jungle Girl. I consider the new title a marginal improvement, though not ideal. Still, it does accurately hint that the story dabbles in lost world tropes. Our hero, Gordon King, is a man of leisure; a doctor with independent means and thus no need to practice his profession; a former college athlete specializing in the javelin throw. He enters a Cambodian jungle as an amateur archaeologist and is immediately lost. This vast jungle is the location of two utterly secluded, warring city states with no contact with the outside world. King is injured, starved, and endures what he believes is a hallucinogenic fever. He saves an important man from a tiger and is nursed to health by two escaped slaves. He encounters a beautiful girl, falls in love, becomes a soldier for one of the city states, abducts the girl from a king, is recaptured, becomes a prince, fights in a pitched battle atop an elephant, etc. Plenty of action. It never really stops. I appreciate that Gordon King’s background as both a physician and a javelin thrower become essential to the plot, rather than being mere background information.

Weak points? I supposed. It feels rather slight. The subplot with the primitive semi-human brute is abandoned, the mystery of his existence/racial identity never resolved. The potential love triangle involving King’s childhood girl next door friend/potential girlfriend is never really developed. As with most of this sort of tale, it traffics in coincidence and sheer luck. But the vigorous, forward driving nature of the narrative moves the reader rapidly past any inclination to indulge in pettifoggery.

So, in all a pleasant way to pass a few hours, if not much more than that. And why does it need to be more?

Now, on to commercial matters. I’ve signed a contract for another short story. This makes me happy. Once the publication is available for purchase, I’ll provide the relevant details. If you cannot possibly wait to get your hands on something I’ve written, you have any number of options. Pick up something and enjoy.

October 27, 2024

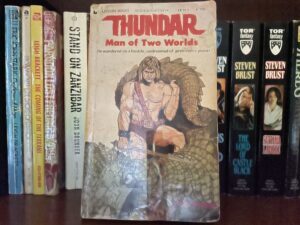

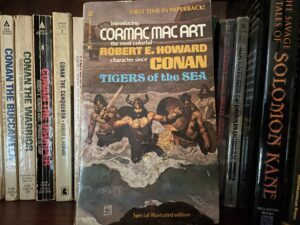

Two Quick Shots: Thundar and Tigers of the Sea

Thundar: Man of Two Worlds was meant as the first in a series, judging by the textual evidence. It is the work of John Bloodstone (that is, Stuart J. Byrne, who labored in the speculative fiction mines in the latter half of the Twentieth Century). Thundar is Edgar Rice Burroughs filtered through Lin Carter. The debt to ERB is evident from the beginning: a narrator revealing how he’d come into possession of the manuscript that provides the bulk of the novel. The debt only deepens with the Tarzan and Caspak elements later on. Lin Carter’s fingerprints show in the gleeful mixture of subgenres: lost world/lost race; time travel; super-science blending with heroic fiction. It isn’t quite as bonkers as the Worlds End books, but doesn’t pull any punches either. All that aside, it was a lot of fun. Quick, fast-paced, and inventive. Unfortunately it leaves many of the mysteries and questions to be answered in the follow-up volume(s) which never appeared.

Tigers of the Sea collects Robert E. Howard’s Cormac Mac Art stories, two of which are finished by Richard Tierney. The introduction is a good primer on REH’s heroes and where Cormac Mac Art fits within the pantheon. The stories in question fall into the historical adventure category (with the exception of the final one, in which our heroes unquestionably tangle with the supernatural.) Yet the introduction suggests an intriguing path linking all of Howard’s sword-swingers, from Kull to El Borak. The change of writers is evident in the first story finished by Tierney, but it still reads tolerably well. Overall, the collection is a fine read if you, like me, enjoy historical action/adventure.

For some action/adventure of the non-historical variety, pick up a copy of my novel Thick As Thieves.

October 20, 2024

The Ship of Ishtar

Look, The Ship of Ishtar is an unusual book. There’s no question of that. It dispenses with traditional tropes.�� A. Merritt does not tread familiar fantasy paths. He picks his own unexpected tangent and proceeds pellmell along it. The pocket universe he creates and its rules appear initially quite strange and arbitrary. But in context of the story’s underlying assumption of the reality and power of the ancient Sumerian pantheon, and of the wrath of Ishtar’s vengeful incarnation, it all coheres more or less consistently. But nothing is ever clearly explicated or spelled out. Merritt trusts the reader to figure things out for himself. It is sink or swim aboard The Ship of Ishtar.

So, what is it about? From my reading, it concerns the conflict between Ishtar and Nergal; that is, between generative life and the foulness of the grave. Baldly put, it is about sex and violence. And, perhaps in the final analysis, about love mediating between the two extremities while partaking of aspects of both. You may get something entirely different out of it.

Merritt jumps right into the action. We are introduced immediately to the protagonist being sucked from his own world onto the eponymous ship. (Begin nitpick: Merritt misdates Sargon of Akkad’s reign by about 1,500 years. End very picayune criticism.) John Kenton, the protagonist, is another of Merritt’s WWI vets. (e.g., Larry O’Keefe, The Moonpool.) Kenton adjusts well to (or is predisposed toward) committing brutal acts of violence, enslavement, sexual aggression. He’s not a model of genteel 20th Century man. In fact, there are hints that he was predestined to voyage on the Ship of Ishtar, which is stuck like a fly in amber in a perpetually primitive pocket world. For example, Kenton already possessed the sword of Nabu, which plays important roles in the narrative. He is familiar with the language (written and spoken) as well as the poetry of Uruk. Merritt deliberately notes that Kenton grows while on the ship, not merely in strength but actually in height as well. This supernatural result suggests that he is (or was fated to become) a focus or avatar if one accepts that attributes beyond those of ordinary man are necessary to handle a numinous visitation. Thus supernally gifted he is able later to receive direct and immediate communications from the gods. And more, he ends up serving as judge for the central conflict. Does his capacity to judge the gods themselves indicate he might be one himself? Merritt writes, “‘Of course,’ said Kenton naively, and with no ironic intention, ‘I am no god…'”

Then there is the glorious redhead Sharane. Another of Merrit’s priestesses or numinous avatars, possessed by gods, monsters, or aliens. Loa-ridden, if you will. Sharane is, on occasion, the vessel of Ishtar herself. Sharane’s reluctant, contemptuous, even spiteful early attraction to Kenton is drawn out to a satisfactory length. Her love for Kenton, and her resultant fate, are adumbrated by the loves and fates of two other women in the tale, a point which perhaps should be considered in light of the thesis of Ship.

I recall feeling a sense of disappointment at the ending the first time I read this. Perhaps my tastes are overly simplistic: I like happy endings, a triumphant hero gaining his reward. That’s not to say I don’t appreciate the bittersweet: Frodo sailing away from the Grey Havens; King Arthur floating off on the barge to Avalon. But tragic characters such as, for example, Elric are a bit harder of a sell for me. However, I think I have a better understanding of both the story Merritt was trying to tell and for the character of Kenton this read through. Appreciating the story from his perspective rather than my own, and having a better grasp of the story’s metaphysical revelations regarding the nature of love, his ending is, in a sense, a happy one. A eucatastrophe, if you will. (And given the hints of an afterlife for the lovers…)

If any of the foregoing suggests that the narrative of Ship is tedious, I apologize for the inadvertent misdirection. The book is full of rousing fight scenes, heroics, and battles on sea and land. It does not, in short, lack for action. It’s just that there is more to it than straightforward, two-fisted action (not that there is anything wrong with straightforward, two-fisted action), and that’s what I concentrated my comments upon.

I’d like to end this with a compliment directed toward Merritt’s descriptive gift. His work features beautifully limned pictures of light, form, and movement that he clearly had fully envisioned to the minutest detail. More importantly, he possessed the skill to masterfully convey his imagination on the page; a rare confluence of the skills of the technical writer and poet. Many are gifted with imagination. Few can impart those visions to others. Merritt could. (If I have previously downplayed his skill in the slightest, I hereby retract and beg your indulgence.) If you want to pick up a copy for yourself, please note that DMR is releasing a Centennial Edition in November.

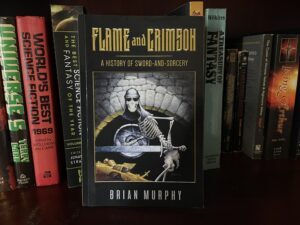

I am writing this post from Orycon 44, in Portland, Oregon. The convention was kind enough to issue me yet another invitation to blather on panels. Of note was the Saturday panel, Sword-and-Sorcery 101, at which I shamelessly cribbed from Brian Murphy’s Flame and Crimson. I also sold several books. Speaking of which, herein follows the obligatory self-promotion. (We all have bills to pay.) Aethon Books has undertaken the effort and expense of publishing all four volumes of Semi-Autos and Sorcery. Now the series is also available in collected format, as both digital and audio books. Get yours today.��

Bonus con pictures.

October 13, 2024

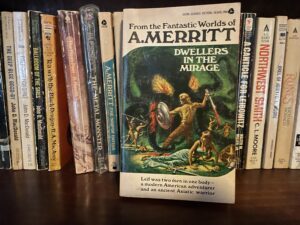

Re-reading Dwellers in the Mirage. Blended Whisky.

A. Merritt‘s Dwellers in the Mirage is a farrago of elements, blending almost perfectly in a heroic fantasy adventure. I wonder, though, if some of the elements are intended to be taken seriously, or if some were included simply because Merritt was having fun, seeing what he could get away with. I mean we’ve got an octopoid malevolent god from beyond the stars (or another dimension, or something) by the name of Khalk’ru. Ring any bells? We have a lost world, a hidden valley in the Alaskan wilderness hidden beneath a mirage-producing layer of geothermal steam. (Or something like that.) We have the Uighers of western China revealed as the degenerate remnant of a proto-Nordic race, whose unmixed bloodline is later encountered in the lost world. (Note such fantastic cognates as Ayjir for Aesir. Yodin for Odin. A gender-swapped Luka for Loki. Etc. It’s like an Easter Egg hunt hidden within the novel.) Then there are Indian myths, most notably the Little People, also encountered with the mirage-concealed valley.

I won’t say that the combination of elements shouldn’t work. Clearly it does, and works well. Much of the best, most entertaining fiction is a combination of disparate influences. Why shouldn’t it work? I had a wonderful time revisiting this book.

Quibbles: I would have liked a bit more of the relationship of Leif and Jim, if only to provide a deeper motivation for Jim’s action and perhaps a greater emotional payoff. The Little People are never explained. Neither are the river serpents, nor the giant leeches (other than a vague suggestion of a Lost World-type continuation of megafauna from a prior epoch, though this is never developed.) Nor is there a reason proposed for the disproportionate number of women or the lessened height of the men. Merritt flings a few strands of explanation against the wall for Khalk’ru, I suppose leaving it up to the reader to see which one sticks. And it is all right. This is a fantasy. We don’t need an explanation for the Witch-woman’s ability to converse with wolves. We don’t need to know the origin of the Rrrllya, nor in what manner the ancient sentience of Dwayanu comes to merge with that of Leif — ancestral memory, reincarnation, etc. It doesn’t matter if the action of the story and the investment in the fate of the characters carries the reader through.

And here it does, going down like a fine, blended whisky. Not everything needs to be a single malt.

There’s nothing wrong with a six-pack, either. Or a four-pack for that matter. Get yours today.

October 6, 2024

Flame and Crimson. Rock On.

Flame and Crimson is Brian Murphy’s affectionate yet fair examination and analysis of the Sword-and-Sorcery sub-genre of Fantasy. (Disclaimer: Brian is an acquaintance. So factor in whatever bias you like to what follows.) Published in 2019, F&C adds a significant component to the renaissance of S&S.

Dissection requires a corpse, and vivisection is hardly an improvement. A close examination of something you enjoy always carries with it the risk of diminishing that enjoyment. You want to eat the sausage, not ponder the meat grinder and intestine stuffing. Happily, F&C does not blunt the appetite for those who feast in the halls of S&S. Instead Murphy examines the sub-genre in entertaining, exhaustive (though not exhausting) detail. Like a skilled waiter, he describes the dish being served in a manner that only enhances the dining experience.

Murphy provides S&S definitions, literary origins, a history, analysis, and cultural impact. He offers useful biographical information about the major players, and lays out their conflicting opinions, philosophies, and thematic shibboleths without taking sides. Plenty of inside baseball stuff, and fun to read even for those already relatively familiar with most of it.

It is game day, so I have to wrap this up. But before I go, the obligatory self-promotion. The four-volume set of Semi-Autos and Sorcery remains a good deal.

September 29, 2024

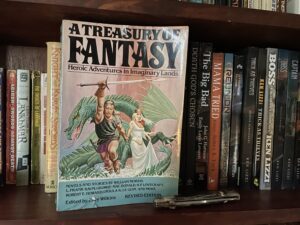

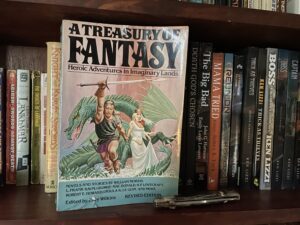

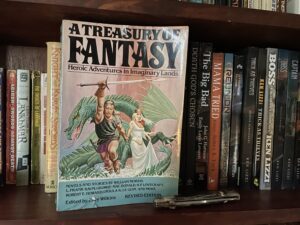

Part III of a Review of “A Treasury of Fantasy.” (REH Has Entered the Chat.)

Following is my review of the last half of A Treasury of Fantasy. Part I is here. Part II here.

The Wood Beyond the World. William Morris. This is not my first Morris novel, though it is, perhaps, my favorite thus far. Morris continues to employ deliberately archaic language, as one might expect. I still appreciate it, yet it often lends itself more to telling rather than showing. Thus it functions in two ways as a sort of throwback to earlier romances.

Morris doesn’t seem to have had an ending in mind when he commenced his tale of Walter Goldings, scion of a rich merchant house and troubled by an unfortunate marriage to a faithless wife. With his father’s blessing, Walter takes ship to foreign ports to start afresh. Before embarking he witnesses a Dwarf, a Lady, and a thrall Maid boarding another ship. A shipwreck on a distant shore — in which is the titular Wood Beyond the World, a title that seems possess no relevance or import beyond sounding cool — leads him to encounter the strange trio again. Adventures ensue.

The positives:

Walter’s old man deserves mention. He kindly acquiesces to his son’s request to roam and offers to deal with the fallout that must inevitably arise from the failed marriage. Walter gets a report of his father’s death from the resulting battle with the house of the (ex) wife. That report includes this ice cold line: “Yea, in his bed he died; but first he was somewhat sword-bitten.” Somewhat sword-bitten. Stellar.

It was refreshing to shift from the Victorian moralizing of MacDonald in the prior novel to the gray, situational ethics of Morris, including thinly veiled sex. And more, we have a protagonist actively pursuing his interests rather than observing events befall him. “…Walter…deemed…that it was little manly to be as the pawn upon the board, pushed about by the will of others.” (pg. 306.)

The negatives:

Morris seems to have either gotten bored or forgot where he was going with the story. To employ an apt idiom, he failed to stick the landing. The ending doesn’t follow from any established acts or foreshadowing. Loose ends are left flapping in the breeze. The island or continent of the “Wood Beyond the World” while introduced in a fashion encouraging hopes of solid, consistent world-building, turns into an out-of-left field fairy tale land of unlikely happy endings at odds with prior descriptions of the place. And the intriguing, ambiguous hints concerning the nature of Walter’s love interest (the Maid, who turns out to be an impressively quick-witted, steel-nerved conniver) never really lead anywhere. A missed opportunity, there. The insinuations that she was misleading Walter, pursuing schemes of her own, could have been explored. Still, a short novel worth reading.

The Master Key. L. Frank Baum. The title has the following subheadings: An Electrical Fairy Tale. Founded upon the Mysteries of Electricity and the Optimism of its devotees. It was written for boys, but others may read it.

As one might expect from Baum, this is one is a children’s story. It might easily be classified as science-fiction rather than fantasy but for Baum’s utter disinterest in the actual science and the conceit that all the novel inventions are given to the protagonist by an accidently summoned genie, the Demon of Electricity. The inventions are interesting and it is fun to consider them from the perspective of a century and a quarter later. Did Baum foresee tasers or the internet accessible in the palm of your hand? Of course not. But one can’t help comparing the gadgets he proposed with what actually exists today. The episodic adventures are ones I would have thoroughly enjoyed when I was, say, twelve. The action and plucky courage of the boy hero would have appealed to me. I’m not sure how well it fits into this particular collection. And the ending irritated me; Baum and I would not have seen eye-to-eye on technology, humanity, and individual freedom.

The Doom that Came to Sarnath. H.P. Lovecraft. A classic. I have written about it before here.

Swords of the Purple Kingdom. Robert E. Howard. The anthology is really finishing up strong. Kull! I don’t think I’ve reviewed this one before. Usually it is a Conan story that ends up in these anthologies, not King Kull. This one is compact, fast-paced, and features all the elements you want from a sword-swinging Howard fantasy: villainous subterfuge, evil magicians, a plucky damsel, feats of strength, courageous heroes facing courageous foes in blood-drenched battle. What’s not to like?

The Rule of Names. Ursula K. Le Guin. An Earthsea short story written in the charming style of The Hobbit or, say James P. Blaylock’s Balumnia novels. The twee language and setting belie the rather dark end, though it is an end that isn’t hard to see coming from the get-go. I’m not the world’s greatest Earthsea fan, but this is a good story.

So, A Treasure of Fantasy provides an interesting progression covering about a thousand years of the evolution of fantasy. What selections would you have made to fulfill the same brief; that is to provide exemplars of the styles and trends of fantasy fiction over the course of Western Civilization from circa 1000 AD? I haven’t sat down and drafted my own selections. But I think I might swap out Phantastes for The Castle of Otranto and perhaps trade The Master Key for Jurgen.

Now, on to the announcement and book-hawking portion of the post. I will be a panelist at Orycon this year. If you happen to be in PDX the weekend of October 18-20 drop by and say hello. My schedule is as follows (title, room, date/time):

Reading. Grant. Oct. 18 4:00.

Essential Fantasy Novels. Morrison. Oct. 19 1:00.

Sword and Sorcery 101. Morrison. Oct. 19 2:00.

Fantasy Before Tolkien. Morrison. Oct. 19 5:00.

Pulp Fantasy! Morrison. Oct. 20 1:00.

Looks like I’ll become well acquainted with the Morrison room. If you’re interested in giving any of my stuff a look before then, why not pick up the four-volume set of Semi-Autos and Sorcery?

September 22, 2024

Part II of a Review of “A Treasury of Fantasy.” “Phantastes.”

Part II of my review of A Treasury of Fantasy covers only one entry, but it accounts for a good quarter of the length of the anthology. Part I can be found here. The selection in question is George MacDonald’s Phantastes. A Faerie Romance for Men and Women.

The first chapter of Phantastes reminds me of Lilith, his later, perhaps more mature work that I’ve covered previously. Both begin with a wealthy young man living in a grand estate and coming into his inheritance only to almost immediately meet a supernatural creature who sets his feet on the path of fantastical adventure. A couple of general notes I found of interest: The sentient — and apparently mobile — trees of early in the book can’t help but call to mind the Old Forest, Fangorn, Old Man Willow, and the Ents. The faeries are largely of the Victorian mold and thus somewhat diminish the undercurrent of menace a Tolkien enthusiast might prefer to encounter in the Perilous Realm.

The story becomes rather episodic as the narrator traverses the forest, blundering into one adventure after another (in the tradition of Broceliande and other such numinous forests.) Anodos, our narrator (“Anodos” means “pathless” in Greek, which is a rather on the nose name given his seemingly pointless meandering) is a rather feckless sort of hero, being delivered from perils not by his own skill, daring, or native luck, but by last minute rescuers. We get hints that the fairy land and the mundane world in some ways overlap, especially when one holds a positive, rosy outlook. But a negative, bitter, or incurious attitude obscures the wonders, beauties, (and dangers) of the fairy world.

��“As through the hard rock go the branching of silver veins, as into the solid land run the creeks and gulfs from the unresting sea; as the lights and influences of the�� upper worlds sink silently through the earth’s atmosphere, so doth Faerie invade the world of men and sometimes startle the common eye with an association of cause and effect, when between the two no connecting links can be traced.” (p. 183.)

Eventually we get more of an inkling as to the thesis of the story. It is, it seems, a moral journey. The distant echoes of Pilgrim’s Progress are inescapable, though this isn’t so directly theological. The varied and disjointed adventures appear allegorical in nature. The intent of such allegories, I confess, may have well eluded me more than once. Still, the thrust seems to be Anodos’ personal and/or spiritual growth as he wanders without seeming purpose through increasingly bizarre (but gorgeously imagined) scenes and scenarios. He gains and loses a shadow (sin, presumably), falls in love and pursues the object of his affection, becomes a martial hero, indeed a knight. Yet all of this leads only to his discovery that it is not such pursuits that necessarily make the man, but rather selflessness and service to others, even if that means recognizing that his object of affection is better off with another. The clearest evidence of his growth and the purpose of the novel seems to me found in page 242:

��“I learned that it is better, a thousand-fold, for a proud man to fail and be humbled, than to hold up his head in his pride and fancied innocence. I learned that he that will be a hero, will barely be a man; that he that will be nothing but a doer of his work, is sure of his manhood. In nothing was my ideal lowered, or dimmed, or grown less precious. I only saw it too plainly, to set myself for a moment beside it.�� Indeed, my ideal soon became my life; whereas, formerly, my life had consisted in a vain attempt to behold, if not my ideal in myself, at least myself in my ideal.”

Anodos ultimately becomes a better man through an act of self-sacrifice performed from pure altruism rather than self-conscious heroism. And there is, more or less, a happy ending, though one that fails to connect with the opening of the book and tie-up loose ends (perhaps too much of a modern/technical criticism.)

I appreciate the quality of the work done. Many of the tales within the tale are compelling and entertaining, including those in verse (and there is a great deal of verse.) The imagery and sheer idiosyncratic, one-of-a-kind creativity on display is worth the trip through. Once, anyway. However, some of my feelings can best be summed up by the quote from the knight who truly is a hero in the story: “You see this Fairy Land is full of oddities and all sorts of incredibly ridiculous things, which a man is compelled to meet and treat as real existences, although all the time he feels foolish for doing so.” That’s rather how I saw it. Much of it seemed the narrator’s ride through a carnival sideshow, viewing interesting things and characters, but generally lacking interaction with them.

I suppose Mac Donald, however, might feel that such viewings helped guide the protagonist to his epiphany; the whole point of which is summed up in page 254:

“…it is by loving, and not by being loved, that one can come nearest the soul of another.”

And that is perfectly valid. It comes down to why one is reading fantasy, at least on a given day. If you are in the mood for edification and curious, beautifully oneiric scenery this is an excellent choice. If, however, you are in the mood for something rather more heroic and action-filled, Phantastes might leave you wanting. We’ll see if the next selection of A Treasure of Fantasy is a somewhat less moralizing entry. If you are currently in the mood for action-filled, heroic fiction (I would dream of attempting to compete with the Reverend MacDonald in the arena of edifying and uplifting) why not give this a try?

September 15, 2024

Part I of a Review of “A Treasury of Fantasy.”

Today I’m going to cover the first quarter of the contents of A Treasury of Fantasy. This early 1980’s volume contains a chronologically arranged selection of fantasy, and bears the subtitle “Heroic Adventures in Imaginary Lands.” Interestingly, the stories chosen come from no farther back than the Volsunga Saga, circa 1270. I suppose that decision makes a degree of sense. Starting with, say the Epic of Gilgamesh, would result in a book at least twice as thick as the already hefty tome under review. There is an open question whether traditional legends, myths, and fairy tales are equivalent to what is considered to form the genre currently labeled fantasy. But that’s a debate for another time (if ever.) So, on to the selections.

The Story of Sigurd, from the Volsunga Saga. Translated from the Icelandic by Eirikr Magnusson and William Morris. That Northern Thing, which matches for grim tragedy anything the Greeks produced. The outlook on life expressed feels almost alien: fatalistic, bloodthirsty, nakedly avaricious. The focus on magical runes and the use thereof is interesting. I can’t imagine at this point there is anyone who doesn’t recognized the debt Tolkien’s The Children of Hurin owes to the Volsunga Saga. This is essential reading perhaps, but not necessarily the most pleasant.

The Quest of the Holy Graal. Mrs. Andrew Lang. Hard to know what to make of the assorted adventures, recounted as barebones outlines of events. More importantly, what is represented by the quest? The unfolding of the search establishes a certain moral hierarchy, one in which martial skill is often (but not always) directly correlated to virtue. But virtue to what end? The religious nature of the quest seems clear, and the most virtuous die to go their final reward. But the quest itself leads directly to the downfall of King Arthur’s court, as half of the Knights of the Round Table perish in pursuit of the Holy Grail, leaving the kingdom vulnerable. So, is the object sought (or the quest for it) in fact a form of evil? Or was it an essential good, necessary to fulfill Arthur’s tragic destiny and move history on from a beautiful, but ultimately stagnant springtime? To quote Tennyson,

“The old order changes, yielding place to new,

And God fulfills himself in many ways,

Lest one good custom should corrupt the world….”

Either way, it was good to encounter all these old familiar names again.

The Enchantment of Lionarda. From Palmerin of England. Franciso de Moraes. This is one of the few knightly romances Cervantes deemed worthy of survival. Palmerin is one of many off-shoots of Amadis of Gaul. While interesting, this selection lacks punch. All the obstacles Palmerin faces are mere illusions. Still, after the dry recitation of encounters in the Graal Quest, it is nice to read a richer narrative, one in which events are described in detail rather than baldly stated. The story telling from this point becomes recognizably modern.

The Elves. Johann Ludwig Tieck. Ultimately tragic, another glimpse of the Perilous Realm. If the elves weren’t quite so twee, portrayed as eternal children, this version would align reasonably well with Tolkien’s (c.f. Smith of Wootton Major.) The tale contains suggestions of the old Nordic concept of the Alfar and some aspects that would fit (uncomfortably, perhaps) with the elvish world of Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword. The dark undercurrents of traditional fairy tales are surface level in this one.

The King of the Golden River. John Ruskin. A droll fairy tale in the vein of Hans Christian Anderson, though with more humor and less pathos. The supernatural creatures are presented with color and wit. It is a proverb of virtue and vice, with the dull nutrition of the message encased in a flavorful delivery vehicle, like coating a dog’s pill in peanut butter.

I will return with part II at some, as yet unspecified date in the future. But if you want to read something else from me right away, why not pick something out from here?

September 8, 2024

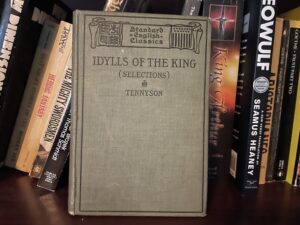

Idylls of the King. Return Again to the Matter of Britain.

I doubt I could recall the sheer number — let alone the titles — of all the books, comics, short stories, films, and television shows I have consumed based upon the tales of King Arthur. Clearly the stuff resonates with creators, or there wouldn’t be so much of it. And equally clearly it resonates with me.

I was visiting friends and family in Oregon a few moths back. In an antique store I picked up a volume (copyright 1903) of selections from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Idylls of the King. I do not pretend to possess the qualifications or aptitude to critique poetry, nor even the interest in developing the qualifications or aptitude. But I do enjoy revisiting the Arthurian Legends in their multitudinous variations and incarnations. And Idylls of the King is one of the major incarnations.

Tennyson wrote the Idylls in blank verse. So those looking for rhymes will be disappointed. But it flows. For those interested in the nuts and bolts of iambic pentameter, meter, anapest, spondees, trochees and the like, this particular volume contains a primer of sorts. Personally I think reading it aloud in an attempt to follow the rules of scansion would be a mistake. Merely reading it as one would a novel soon drops you into the flow. It feels melodic.

More importantly for me, it reads well. The three idylls selected are terrific. Unlike the spare recitation of events provided by earlier compilations of the legends, (e.g., Le Morte d’Arthur), Tennyson brings a poet’s (or dramatist’s) eye to detail, motivation, and character.

Gareth and Lynette is the first selection. Tennyson draws wonderful character portraits of the Kitchen Knight and the haughty, dismissive maid. The action scenes, rather than consisting of “Knight X encountered Knight Y and unhorsed him,” are fleshed out. It isn’t Robert E. Howard level visceral mayhem, but Tennyson does a fine job conveying the blood and bone-breaking violence. Lynette’s gradual appreciation of Gareth is well-done.

Lancelot and Elaine is second. The central sin that undoes the glories of Camelot is on full display here, even though the central plot is the tragedy of the unrequited love of Elaine. This is sort of a longer variation of Tennyson’s take on the same story, The Lady of Shallot. I’m resisting quoting bits here. Read it yourself for portraits of the guilty lovers and the husband perhaps willfully withholding suspicion.

The third Idyll is The Passing of Arthur. It is haunting. No matter how many times you read about it, Arthur’s end is always tragic and moving, in light of what could have been. Tennyson’s version can be appreciated by those steeped in Arthurian lore, but also just as easily by those who have merely watched Excalibur and liked it.

I’m glad I picked up this little volume. Of course it has only whetted my appetite for the complete work.

If you are interested in picking up a complete work, the four-volume set of Semi-Autos and Sorcery is available, and at remarkably reasonable rate.

September 1, 2024

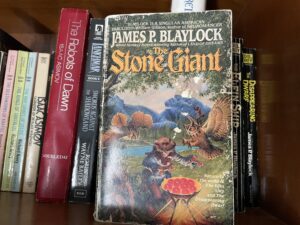

James P. Blaylock’s “The Stone Giant”

James P. Blaylock’s twee trilogy comes to close, oddly enough with a beginning of sorts. The Stone Giant does not pick up with the further adventures of Jonathan Bing. Instead it leaps back in time to the commencement of the career of the roguish Theophile Escargot. At first this might strike the reader as an odd choice. I, for one, was initially disappointed. Escargot was not a favorite character and I wanted to catch up with what the cheesemaker Bing might have gotten himself into next.

Yet it didn’t take long for Blaylock to draw me into the Escargot’s story. It begins as a bit of a picaresque, and I’m a sucker for that sort of tale. And as Blaylock pushes the hapless Escargot into worse and worse trouble, he starts ladling out references to people and items we readers have encountered before (and Escargot will bump into again in his future.) So it seems Blaylock decided he wanted to explain some mysteries via prequel rather than sequel. He does so with humor, verve, and a nod to Verne’s Captain Nemo. The story culminates with a grand, climactic battle. It is delivered in a somewhat muddled fashion, yet Blaylock carries it through on sheer eventfulness and momentum. He leaves us without closure, but it works well since we readers know that this is merely the start of many more strange adventures to come for Theophile Escargot.

The Stone Giant is, perhaps, the lesser of the three books. Still

Warning: This book may induce a desire for pie.

If, instead of pie, you are interested in something to read, let me again recommend the recently released four-book set of Semi-Autos and Sorcery. It’s priced right in both digital and audio formats. Give it a try and let me know what you think.