Ken Lizzi's Blog, page 9

April 7, 2024

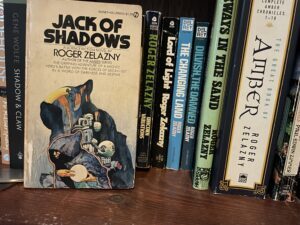

Jack of Shadows. A Dark Gem of a Novel.

I have at last managed to fill in a lacuna in my Appendix N reading. Jack of Shadows is, in someways, Roger Zelazny condensed to the quintessence. A synecdoche of a sort. If you’ve read much Zelazny, you’ll recognize themes: resurrection, from Lord of Light; the corrupting nature of absolute power, from Amber; the ambiguously amoral nature of demonic and monstrous beings, from Dilvish the Damned and A Night in the Lonesome October.

Jack of Shadows is set on a tidally locked earth. Whether that occurred naturally or supernaturally is left unstated, though a supernatural origin is hinted at. The dark side is the realm of magic and generally evil or morally equivocal creatures. The light side (which gets short shrift) is the realm of science, essentially 1970s America. (Commence Digression: Reading this section, in which Zelazny refers to supersonic flight as a matter of course, left me feeling melancholy. There was a time during which we went to the moon, traveled in supersonic passenger jets, and generated electricity through nuclear power. Had those technologies been allowed to develop along the same trajectory as computing, medicine, and biology, what glorious existence would we be enjoying? End Digression.)

I won’t summarize the plot. That’s something for the reader to enjoy and puzzle out himself, with its deliberately unreliable narrators. Jack begins as a sort of roguish, amoral thief. An antihero. His overwhelming, all consuming desire for revenge leads him along a path toward villainy, to the extent that he becomes in effect the traditional fantasy Dark Lord. There is a luciferian quality to him, which is emphasized by his sole friendship with a bound, gigantic figure named Morningstar. His remaining redeeming features: love, friendship, and gratitude, impel him on a sort of descent into the underworld to perform an apocalyptic act of destruction which leads to a sort of Promethean redemption.

All this and swordplay, magic, weird spectacles, and bizarre settings compacted to 142 pages. There is the merest hint of Elric about the book. Just a whiff, nothing more. Readers who want the plot and setting neatly set out, with the internal logic fully explicated might not enjoy this one nearly as much as I did. Sometimes I feel the same way, wanting something more de Campian. But Zelazny — to my mind, at any rate — neatly pulled off the trick of satisfactorily providing nothing more than hints, suggestions, and allusions.

If this web log post put you in the mood for reading a fantasy set somewhat off the beaten path, give Thick as Thieves a try. You’ll enjoy it. (I mean, just because I have something to gain is no reason not to trust me.)

March 31, 2024

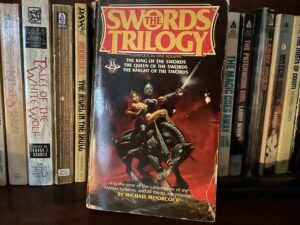

The Swords Trilogy. Psychedelic Sword and Sorcery

It seems impossible to write about a book without invoking the reviewers personal connection with the book and the author. Age, circumstance, and location can have an effect on how a book hits any given reader. I won’t be able to perform the impossible, you may be surprised to learn. I’ve made no secret that I’m not the world’s greatest fan of Michael Moorcock. His works did not hold up for me as I aged (I won’t say matured.) Your mileage, as they say, may vary. And that’s fine with me. The point is that I still retained a soft spot for The Chronicles of Corum, the follow up to The Swords Trilogy. I read it three or four times as a youth. Perhaps it was the riffs on Irish mythology, which I was exploring at the time. Perhaps it was that terrific cover. I don’t know. Whatever reason, it was one of the last of the Moorcock paperbacks I sold off. I’ve since collected one or two, but have few of the Eternal Champion tales on ��my shelves. When I saw a copy of The Swords Trilogy in quite decent condition at the used bookstore I hesitated only briefly. That one I’d read only once and had only limited recollection of. I recall it being vivid, colorful, and weird. Why not take a chance on a re-read?

I am, on balance (heh) glad I did so. The Swords Trilogy collects three short novels: The Knight of Swords, The Queen of Swords, and The King of Swords. Each novel depicts the efforts of Corum Jhaelen Irsei to defeat the titular Lord ��of Chaos in each of three closely related planes/dimensions. Corum is an avatar of the Eternal Champion (like Elric), of a race similar to the Melniboneans. So one of Moorcocks elves by other names. Corum is similarly moody and broody. The first novel provides us ample reason for his attitude, as humans slaughter all of his race, leaving him the last of the Vadhagh. (Or, so he believes.) Thus he has a quest for revenge, which runs through all three books. But more immediately he gets caught up in scenarios that require him, as I mentioned, to defeat the god of each of three dimensions.

If you’ve read any of the Eternal Champion novels, none of this will be particularly new. In fact the last book ties in directly to one of Elric’s stories. Some familiarity with the Eternal Champion Cycle isn’t necessary, but it does add a dimension. In many ways, then, this isn’t something I should have enjoyed that much. Moorcock’s idiosyncratic thematic shibboleths are on full display. But the sheer velocity of the narrative helped carry me right past them without even an eye roll. (Well, maybe one or two. “…the mourning wind found an echo of sadness in their own souls….” Ugh.)

That narrative speed, coupled with sheer, infinitely creative bravura, which takes you on a blistering tour through epically gonzo settings following one after another, is what provided the pleasure in this re-read. Short paragraphs provide the illusion of velocity. Brief, punchy descriptions of the bizarre and outre keep the reader zipping past plot holes, lack of cohesion, slapdash world building, and contradictory timelines. None of that matters here. It’s all about the psychedelic light show. If the show is good, certain issues with plot coherence are irrelevant. And the show is good. I had fun.

I don’t imagine I’ll be picking up another copy of The Chronicles of Corum anytime soon, however. Instead I’ll walk away leaving Corum to a happy ever after, pretending the inevitable tragic end of the second series never occurs.

So, a positive review. Keep that fact in mind as I move on to the commercial stage of today’s web log post. Looking for something to read? (Here imagine that I am closing my eyes and tossing a dart at the vanity shelf.) Pick up a copy of Under Strange Suns. The reviews are positive, for whatever that is worth.

March 24, 2024

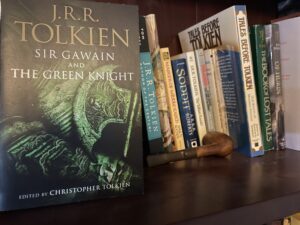

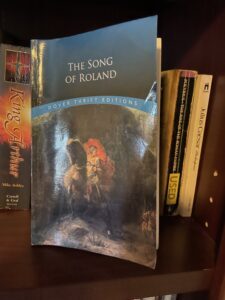

The Green Knight, Roland, and More Delving into Roots

Stories cannot help but build on prior stories. Conventions story tellers are not even aware they are employing all derive from some earlier source. Even the wild and wooly field of speculative fiction, despite its reasonable claim to novelty, owes debts that can be traced back to Homer, if not earlier.

J.R.R. Tolkien, in addition to his own creative endeavors, also translated the works of creators of tales in defunct languages. I picked up a copy of the volume edited by Christopher Tolkien, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The book, in addition to that famous story, also contains��Pearl and Sir Orfeo. I was familiar with the basic events of Green Knight from prior readings of the corpus of Arthurian legends. (And yes, if you’re asking, I did see the recent film. I will accept traditional advice and not say anything about it.) Reading the poem and the transcript of the lecture Tolkien gave concerning it and his translation provided a deeper and more nuanced experience than a simple recounting of the particulars. The religious and cultural aspects were interesting. But the tale does lack the action and adventure focus of many of the other legends. Not every Arthurian yarn needs to concern itself with who knocked whom from a horse with a long stick, but I genuinely like that aspect, within reason. Gawain’s fixation on rectitude, on right action and behavior stands out in comparison to other depictions of the character. Here he is not the hothead encountered in other tellings of the legends.

Pearl is religious allegory, a dream visitation from the narrator’s deceased young daughter and a tour of Heaven. I am not the one to offer much comment on this one. After the alliterative verse of Green Knight, it was rather pleasant to encounter rhymes.

Sir Orfeo is something of a variation on the Orpheus myth, though with a happier ending. Instead of a trip through the underworld, there is a visit to Faerie. I rather enjoyed it. It seemed to provide a glimpse at one of Tolkien’s inspirations, the conventions that influenced his creative output, consciously or unconsciously.

The Song of Roland predates the stories Tolkien translated. As King Arthur and ��the Matter of Britain are to England, so Charlemagne and the deeds of the 12 Peers are to France. Entire cycles of stories were created concerning Roland, Olivier, Ogier the Dane, etc., much as they were about Lancelot, Galahad, Percival, etc. As with the Battle of Badon Hill providing some vague factual support for the King Arthur stories, there was an actual battle at Roncevaux that involved some of Charlemagne’s forces being entirely wiped out. But it was by local Basques, not Muslims. Still, there was a fight. And the fight is the focus.

And what a fight. We’re in superhero/mythical territory here. Much as with the early chapters of Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, the battles defy credibility. They aren’t, presumably, intended to be realistic. There are some fine depictions of one on one combat, detailing lance’s spitting opponents, or sword strokes cutting both man and horse in half. Semi-plausible up to a point. But then will ��follow a description of that victorious knight going on to slay hundreds or thousands. Much like in Le Morte d’Arthur. It’s Achille’s-level slaughter before the walls of Troy. More so, even. Roland’s rear guard of 20,000 ends up defeating about a half a million. Roland and Archbishop Turpin, the last two alive, send the remaining few thousand fleeing before succumbing to their wounds. Charlemagne then arrives to take on an even larger army generalled by an even greater villain (as befits the foe of an Emperor.) This army, take note, not only includes men but giants and semi-human monsters. If Zack Snyder ever directed a film adaptation I’m pretty sure these would get vastly more screen time than they got verses. (Note that earlier, in almost an aside, we learn that Turpin kills a sorcerer during the battle. Sadly that potentially interesting incident gets nothing more than a single line.) It’s all pretty wild. Yet so is your average Fast & Furious movie. The tale wasn’t intended to be plausible, merely entertaining.

So it was and thus shall it ever be, or so one can hope. We want our larger than life heroes. We want Beowulf, and Superman, and Breckinridge Elkins, and whomever The Rock is playing this week. That’s what iteration after iteration of Western literature, generation after generation of stories has conditioned us to desire. And that’s fine with me. Programed or not, I like this stuff.

If you like this stuff, you might try some of mine. Give the Semi-Autos and Sorcery series a try. Karl Thorson is rather larger than life himself.

March 17, 2024

Merida and Vicinity

I returned Wednesday from a week in Merida, Mexico. Merida is the capital, and largest city, in the State of Yucatan. MBW, the HA, and I rented an AirBnB and a car for the week’s explorations. We visited the city center, plazas, cathedrals, restaurant row, a chocolate shop, a well-done brewpub, ice cream and gelato shops, etc. We visited the ruins at Uxmal, swam in cenotes, hit the beach in Progresso and in Sisal.

I won’t bore you with all the photos I took. But here are a few covering the trip.

Enormous market. Herein the HA learns in part where her food comes from. She was not pleased.

Enormous market. Herein the HA learns in part where her food comes from. She was not pleased. One of a half-dozen of the statues and monuments we saw in Merida.

One of a half-dozen of the statues and monuments we saw in Merida. Street scene in Merida. Tourist area.

Street scene in Merida. Tourist area. Ditto, except marred by my presence.

Ditto, except marred by my presence. Bacab brewpub. Go. Have the stout. Talk to Fred, formerly of Bend.

Bacab brewpub. Go. Have the stout. Talk to Fred, formerly of Bend. Flight at Bacab.

Flight at Bacab.Various pictures from Uxmal below. I took plenty more. I would have liked to spend more time there, but the temperature that day was brutal.

Cooling off in a cenote.

Cooling off in a cenote. Prior occupant of the cenote?

Prior occupant of the cenote?We spent a day in Progresso on the beach, then shortly before closing time took a boat across to a nature sanctuary with several open air cenotes for more swimming.

The malecon in Progresso.

The malecon in Progresso. Waiting for tacos and beer while the HA played in the sand.

Waiting for tacos and beer while the HA played in the sand.

We got to the quiet seaside town of Sisal the next day. A relaxing change from the touristed Progresso.

Imagine cold beer and a Jimmy Buffet song.

Imagine cold beer and a Jimmy Buffet song.Speaking of beer, I sampled my way through some of the local craft offerings. Mexico still has a way to go in the IPA field, but some others were decent. And I finally had a chance to try pulque, which offered up an intriguing, pleasantly sour bread dough flavor.

Just shoveling in hops doesn’t make for a good IPA.

Just shoveling in hops doesn’t make for a good IPA. A dessert beer. Good, but couldn’t handle that much cloying honey for a second bottle.

A dessert beer. Good, but couldn’t handle that much cloying honey for a second bottle. Decent.

Decent. You should try pulque at least once.

You should try pulque at least once. Not too bad for a custom label beer. The food was much better.

Not too bad for a custom label beer. The food was much better.

March 10, 2024

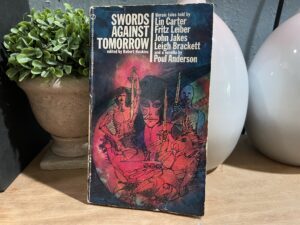

Swords Against Tomorrow: A Wickedly Sharp Collection of Yesterday

I can’t say I get the title. The rather generic — but perfectly acceptable — introduction by Robert Hoskins does not clarify. But what is important is not the title but the contents. And what contents!

The great Poul Anderson leads off with a story I’ve never encountered before, Demon Journey. Apparently it was originally published pseudonymously and not republished until this volume, a couple of decades later. I think I can guess why. I don’t believe Mr. Anderson was particularly proud of this one. The revelations later in the final act are rather unconvincing, the plot depends upon unlikely contrivances, and at least one intriguing — and seemingly important — bit of world building is never paid off. But all that aside, it is still Poul Anderson writing Sword and Sorcery. Even lesser Anderson is good Anderson. This one is pretty long, novella length, and he filled every page with color.

I couldn’t say how many times I’ve read Bazaar of the Bizarre by Fritz Leiber. It doesn’t really matter. I read it again and still enjoyed it.

Lin Carter is third with Vault of Silence. If you’ve read any of the Thongor stories, you know the style of prose you’ll be getting in Vault. He sets up a sort of fantastic, twelfth century Kievan Rus analog, then lets his imagination run wild. I enjoyed it. His character, Kellory, makes a fine archetype for anyone who wants to run a somewhat non-standard wizard in D&D. Only two items diminished my appreciation. One is the fact that a story based on magic use often feels like the writer is cheating being able to set up tension and conflict, then pretending that whatever hoodoo power he’s invented to get the hero out of it is somehow an act of strength and courage. The writer needs to establish the rules in advance, at least hinting at the solution and establishing its courageous nature. That doesn’t occur here. Second, this isn’t a full story. It reads like the first chapter in an epic. Nothing was resolved.

I’ve read Devils in the Walls before. It is one of John Jakes’ better Brak the Barbarian stories. I like it this time through as well. I wonder if anyone writing currently would include the use of a cruciform symbol as a focus of numinous power. It works here, I think, adding layers to the world Brak traverses.

Leigh Brackett contributes Citadel of Lost Ships. It is the only science fiction story, a retro-sf adventure story set in our system with the conceit that the inner planets and moons of the outer planets are inhabited. No swords appear, but it is the only tale to which one might apply the anthology title. It is a frontier story, taking place primarily on and in the orbit of Venus. With its space ship chases, high-tech gun battles, unique alien races, evil governments, and corrupt space station manager it is ��better Star Wars story than, say, Rebel Moon. ��But what else would one expect from Brackett? She was an old hand at this. My only quibble is it inclusion here. It sticks out in an anthology filled with S&S.

Overall, a solid collection. I enjoyed it despite the repeats. Nothing wrong with rereading something you enjoy.

Speaking of reading something you enjoy, I’m guessing you might enjoy Under Strange Suns. Give it a try. Let me know what you think.

March 3, 2024

Convention Weekend and the Thief of Time.

I am in Lebanon, Tennessee this weekend, about twenty minutes outside of Nashville, for a small convention. This is my second appearance here. I had to back out last year, but was happy to make it back to Mike Williamson’s annual gabfest and booze-a-thon. Sarah Hoyt served as Guest of Honor. It was nice to see her again.

I feel a trifle disconnected at the moment. Time seems to behave strangely at these things. I tend to go to be relatively early. Yet on Friday (or, rather Saturday) I glanced at my watch and discovered it was 12:30. And then Saturday (or, rather, this morning) I realized it was 3:00 AM and I was still swapping stories. What happened? How did time slip past at such an accelerated pace?

And now, I suppose, the hours until I head to the airport and fly home will creep along glacially. Strange.

Well, it was a good weekend, seeing familiar acquaintances, and even selling a few books.

Speaking of selling books, feel free to browse through these selections. I, meanwhile, will drink some coffee.

February 25, 2024

The Exotic Enchanter. A Hero’s Homecoming — Eventually.

Here we are with part 4 of my look at the Harold Shea stories. The last part, as far as I am aware. The Exotic Enchanter returns L. Sprague de Camp and Christopher Stasheff to the series as well as adding three additional authors, two of whom co-write a story. The ongoing pursuit of Florimel continues to drive the narrative for a while. As motivations go it is serviceable — it certainly has the benefit of experience behind it. So, on to the first story.

Enchanter Kiev by Roland Green and Frieda Murray. Perhaps not the most clever of titles, but at least it provides a notion of where the characters will find themselves. I’m familiar with Roland Green as a competent adventure scribbler, but I do not recall running across Frieda Murray before. This tale follows up the cliff hanger from the previous volume. Shea and Chalmers are either in Borodin’s opera, Prince Igor, or in the earlier, inspirational work, The Lay of Igor’s Host. Other than some slight knowledge of the period and the area, this is new literary territory for me. The story is fine. It lacks some of the clarity other others have brought to the series. If it isn’t exactly murky, the prose could at times be clearer. Lacking also is the gift of de Camp and Pratt’s I noted in an earlier post: pacing. This one could do with tightening up. It crawls at times, burdened with excess detail. The writers, I guess, wanted to show their work.

Sir Harold and the Hindu King, by Christopher Stasheff. I’m unfamiliar with the tale sends Drs. Shea and Chalmers into. There is early promise of a certain whimsical humor. Sadly that largely vanishes, followed with the occasional droll observation but little actual levity. That’s too bad; the Prophet of Profit was a fun character from whom the reader is led to expect repeat visits. The story becomes rather turgid and I had to push myself to finish it. It isn’t a bad story, merely lackluster. At least the pursue of Florimel storyline is wrapped up. Finally.

Sir Harold of Zodanga. L. Sprague de Cap is back! And with a story set in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barroom! Expectations mount. de Camp answers one question I had about the continuity of a series written over 50 years. It seems that, instead of maintaining a 1940s timeline, de Camp envisions a comic book style continuity in which everything occurs in a continuously flowing now. Thus this story occurs in the 1990s. The story sees Malambroso kidnapping Shea and Belphebe’s daughter and spiriting her off to Barroom. The couple pursues. It is fun to step back onto ERB’s red planet again, though through another author’s filter. In this case the filter is de Camp. Those still irritated at de Camp and Carters’ approach to Robert E. Howard’s Conan oeuvre will likely bristle immediately. de Camp, being who he is, cannot help but “correct” the technical deficiencies of ERB’s science fiction, frequently noting that such things as radium guns were merely exaggerations or inaccuracies on the part of the scrivener of John Carter’s adventures. And that was okay with me, having had some of the same quibbles. At least, okay for a while until it seemed to entirely preoccupy de Camp at the expense of the story. He decamped from grounds of gentle, affectionate teasing into full on Neil deGrasse Tyson territory, apparently abandoning all sense of whimsy and acceptance of fantastic literature conventions. Still the best of the stories so far, and fun when de Camp focused on the adventure.

Harold Shakespeare by Tom Wham. I’m not familiar with Wham’s work. In the culminating tale he takes Shea, Belphebe, and Polacek (remember him?) onto the island of Shakespeare’s The Tempest prior to the advent of Prospero. While it could have been paced a trifle faster it remained engaging. I would have preferred interaction with the great wizard himself, perhaps a brush or two with Caliban. But the story works well enough. Much of the formula is in evidence, though I could have wished Wham would have had Shea working through the science of the magic of this particular world, rather than rehashing the greatest hits of other stories. I suppose this story is in fact a respectful homage. It does serve as sort of coda, wrapping up the series, and reestablishing all the major characters more or less comfortably back in Ohio.

And that, so far as I know, is that for Harold Shea. Is anyone aware of another collection, or perhaps an uncollected story or two? To sum up four posts worth of reviews: the truth is that the real sparkle vanished without Fletcher Pratt. The collaboration of Pratt and de Camp just worked. Every Harold Shea story after varied in quality from mediocre to slightly above average.

For the concluding, commercial portion of the post, I’ll recommend a thematically appropriate work. I wrote Under Strange Suns in part as an homage to ERB’s Barroom. Give it a try.

February 18, 2024

The Enchanter Reborn. Too Many Cooks?

Despite the passing of Fletcher Pratt, Harold Shea lives on. The fantasy humor writer Christopher Stasheff tries to fill in, though the proceedure of story creation differs. The collection The Enchanter Reborn contains, rather than collaborations, individually written stories: two by Stasheff, one by L. Sprague de Camp, one by Holly Lisle, and one by John Maddox Roberts, (the latter two from outlines by de Camp and Stasheff.) So, rather than Pratt and de Camp working together to produce the stories, we have four authors writing individually. How does this change in the recipe affect the product? Let’s find out.

Professor Harold and the Trustees by Stasheff is�� more a refresher, a tidying up of loose ends, and a reset than a true Harold Shea story. Stasheff here, in his return to previously explored worlds, doesn’t truly capture the Pratt and de Camp feel. His actions scenes are slightly off, lacking the technical sport fencing lingo de Camp (I assume it was de Camp, judging from a dozen or so other de Camp books) liked to employ. And Harold seems less the opportunist than he was in Pratt and de Camp’s hands. Much of it seems a pointless exercise, since the purpose is utterly forgotten or dispensed with later on.

Sir Harold and the Goblin King by L. Sprague de Camp. de Camp and Stasheff clearly had not consulted with each other before writing. de Camp’s story directly contradicts Stasheff’s prior entry. In de Camp’s hands Shea reads like Shea again. Innuendo returns to the pages and Shea is slightly more calculating and less absorbed by moral niceties than Stasheff’s version. I’m not an Oz enthusiast and have little familiarity with the characters and setting. But I liked this one.

Sir Harold and the Monkey King, by Christopher Stasheff. I am familiar with the Chinese epic Journey to the West primarily through films, cartoons, graphic novels, and references in other texts. So I don’t know how accurate Stasheff’s take is. But it feels right. Yet neither Shea nor Dr. Chalmers (who accompanies Shea in this episode) attempt to discover and employ the particular magical system of this universe. So, absent one of the tent poles of the Harold Shea stories, this story sags. It still had its moments, though.

Knight and the Enemy by Holly Lisle. Again the lack of a coordinating editor for this anthology reveals itself. Lisle’s story states that it occurs following an excursion to the world of the Aenied. But Roberts’ story, which comes last, takes place in the Aenied. Also, it feels as if there is a missing story, unless I have forgotten an earlier tale that introduces Malambroso. (Which is entirely possible. Feel free to point it out to me.) Lisle’s tale brings Shea and Chalmers into the company of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. And it is a lot of fun, full of humor and adventure. But the cleverest bit is that the story takes place — rather than in Cervantes’ novel — inside the universe as imagined by Cervantes’ character; inside the chanson de gesete warped mind of the Knight of the Woeful Countenance himself. It is gloriously metafictional, a story within a story within a story. Lisle windowframes this herself: Dr. Chalmers, on page 197, says “The universe is not a Chinese puzzlebox, Harold. Universes of fictions within fictions are improbable to the point of ludicrousness and –“. That’s great stuff.

Arms and the Enchanter, by John Maddox Roberts. Roberts has a great knack for colorful, telling detail. He skillfully includes little points showing that this world is Virgil’s conception of the ancient Mediterranean, rather than either Homer’s or the historical record’s. He gets the metafictional aspect, the humor, and the mechanics of magic aspect. He seems to have an excellent grasp of the underlying material; that is, both the Aeneid and the Enchanter stories. So the book ends on a high note, though it also ends with a cliff hanger. Which means there is more to come. Check back next week.

While you are waiting, pick up something of mine. As of this writing, it looks like you can get the entire four volumes of the Semi-Autos and Sorcery series for a good rate.

February 11, 2024

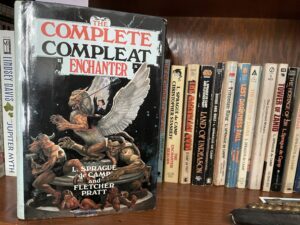

The Complete Compleat Enchanter. Part Two, the Romantic.

Last week I posted about the the first two tales of L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s Harold Shea stories. This week it is time to complete the Complete Compleat Enchanter.

The Castle of Iron sees Shea in the world of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (after a brief stop in Coleridge’s Xanadu.) Shea is now married to Belphebe of Faerie. Due to various complications, she has become Belphegore of the Furioso and has lost her memory. Pursued by a policeman of our world, Shea must recover her, return her memory, and return to the mundane world. Which he does, leaving various psychologists and a policeman stranded.

The Wall of Serpents begins with a sense of domesticity for Mr. and Mrs. Shea. Romance and maturity are increasing themes and motivators in the last three stories. But the responsibility of rescuing the others left in Xanadu drives Shea to once again start up the syllogismobile. He and Belphebe head to the world of the Kalevala, in need of a powerful wizard to draw the others to mythical Finland, and then head back to Ohio. Of course complications arise. And instead of getting back to our world, three of them end up in…

Mythical Ireland, in The Green Magician, the world Harold had been attempting to access his first time out. It proves rather more dangerous than he’d anticipated. They encounter Cuchulainn in one of his fits of temper. That is dangerous in itself. Another danger is his interest in Belphebe. The policeman turns into a major asset, revealing himself to be deeply informed of all things Irish. (That is played for humor, as he is in fact of Polish descent, but figured he’d improve his career opportunities in the police force if he affected to be more Irish than the Irish.) They get caught up in the events of the legend, consult a couple of druids, visit the land of the Sidhe, fight a lake monster, and return home. Though they’ve only managed to bring back the cop, leaving psychologist behind in a couple of different worlds.

So, there we have it. The Complete Enchanter leaves an incomplete story. And that’s okay, because the saga continues, though without Fletcher Pratt and with a variety of authors taking a turn behind the wheel of the syllogismobile. Which means I’ll be back with more posts on the continuing adventures of Harold Shea.

If you’d like to read something else of mine while you’re waiting, there is plenty to chose from. Why not give Reunion a try?

February 4, 2024

The Complete Compleat Enchanter. Part One, of the Making of a Hero.

I re-read books. Yes, I keep going back to the well, or, rather, wells. But if the water is so good — uisce beatha, if you will — what’s wrong with that?

I have the Baen edition of L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s The Complete Compleat Enchanter, which I haven’t read in years. More fool me. It contains the sequentially connected (Short novels? Novellas? I haven’t peformed word counts.) stories The Roaring Trumpet, the Mathematics of Magic, The Castle of Iron, The Wall of Serpents, and The Green Magician. As noted in David Drakes introduction (highly recommended) these were originally published in John W. Campbell’s magazine Unknown, wherein the writing credits were reversed. (Campbell gets a cameo of sorts in Mathematics of Magic.)

So far this week I’ve read through the first two. (Hence, the “Part One” of the title of this post.) The first thing I want to note is the pacing. It is brisk. I find myself breezing through these stories faster than most fiction I pick up nowadays. It’s as if I’m getting to return to the Ken Lizzi of bygone days who had the time and lack of competing demands that allowed him to sit down and read two or three hundred pages in a day. Sure, I’m not reading that fast. Contemporary Ken Lizzi does have those competing demands on his time. Messrs. Pratt and de Camp keep the story moving along, providing all the information and background color the reader needs but not a word more. That allows room for the jokes.

That’s the second thing to note. These stories are funny. Droll might be a better word. But definitely some variety of amusing. On occasion rather boldly amusing for the era. (I finally got around to reading The Ballad of Eskimo Nell, of which Harold Shea, the hero of the stories, quotes a few carefully selected snatches in Mathematics of Magic. Even though redacted, the fact that the doggerel was referenced at all seems rather audacious for the 1940s.) Pratt and de Camp are able to find humor in the Norse myths and Spencer’s Faerie Queene without belittling or mocking the source material.

And they get the source material. They also ground it, looking at the practicalities that would have necessarily accompanied these worlds. I mean, of course they would; this is L. Sprague de Camp writing for John W. Campbell. The nuts and the bolts must be considered. In fact the nuts and the bolts must take primacy of place. Specifically in the Harold Shea stories these nuts and bolts are the workings of the magic system in each world into which the characters transport themselves. (That method of transport provides the initial piece of “science” developed in the narrative.)

Roaring Trumpets takes place at the cusp of Ragnarok. Shea ends up there accidentally, rather than hitting the world of the Irish Mythos he’d been attempting for. Shea is rather a bumbler in this first tale, getting frequently taken down a peg. It is a learning experience for him. And learn he does, for by The Mathematics of Magic (taking place in the quasi-Arthurian/chanson de geste-esque sylvan landscapes of the Faerie Queene) he has grown in confidence and competence, becoming more of the conventional hero he’d considered himself to be.

It’s good stuff. Fun. I’ll be plowing straight on through the rest of the series. If you haven’t already, you might want to give it a try. You might also want to try the Semi-Autos and Sorcery series. I think that’s pretty good, too. Then again, I am biased.