Ken Lizzi's Blog, page 8

June 16, 2024

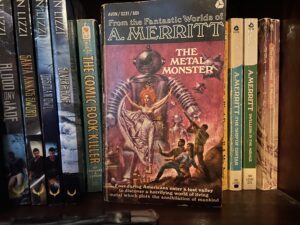

The Polychromatic Prose of A. Merritt’s The Metal Monster

So, what is The Metal Monster? Imagine a concoction of one part She, one part The Moon Pool (natch), one part Lovecraft’s cosmic horror, one part D&D Modrons, and one part Big Hero Six. Blend and strain through A. Merritt’s glorious, vividly colorful, and painstakingly descriptive prose. It ought to make for a masterpiece. Maybe it is, but I found it lesser Merritt. He’s always been somewhat difficult to follow; his style can make it hard to figure out exactly what is going on, and where one thing is in relation to another. The descriptions are exacting, yet are written in such dense detail that it is easy to get lost. (He’d have been a hell of a technical writer.) Still, so long as the story is entertaining, it doesn’t much matter. You can pick up enough to carry on. In this case the story is entertaining…just enough. Little actually happens after an exciting action scene. The bulk of the tale is a travelogue through Merritt’s fantastic visual imagination: a civilization of living machines, of three-dimensional solids that can combine to form any conceivable object and think and act as one.

Therein lies the problem, I think. Other than…showing up, the characters have little impact on the story. The narrative is on rails. The POV character does nothing more than describe what he sees as he whizzes along rather than affecting, directing, or influencing the outcome. At least the final act is…kinetic.

Overall I liked it. It paints a tremendously imaginative, kaleidoscopic vision. I just expect more from Merritt.

Right, now for this commercial message: get your copies of Reunion and Under Strange Suns while you still can. The original editions won’t be available much longer, or so I’ve been informed.

June 9, 2024

The Dice Have Been Cast. NTRPG 2024 in the Rearview Mirror.

The fifth and final day of the North Texas RPG Convention is here. I’m packed and ready to hit the road. It is hard to believe that most of a week can pass seemingly so swiftly. But there you have it.

I restricted myself to purchasing only three books in the dealers’ room, an exercise of staggering will power you should all admire.

I rolled dice with old friends and perhaps some new ones. In brief, I had fun.

Negatives? The hotel is in a restaurant desert. I rode with friends instead of driving, which necessarily limited my meal options. But I didn’t come to Dallas to sample the cuisine.

So, next year? Probably.

And now for distasteful commercialism. Buy my books. (I see the boxed edition of the Semi-Autos and Sorcery series is in the pipeline. Cool.) Thank you for your patronage.

June 2, 2024

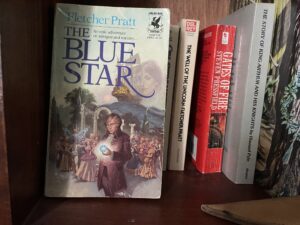

“The Blue Star” Shines

I’ve written before about Fletcher Pratt, incidentally referencing The Blue Star. But it has been years since I’ve read it. It is one of those books pilloried by the scolds and Mrs. Grundy’s who appear like a locust infestation from time to time in the speculative fiction field. Perhaps they have a point and I missed something on my previous read through. Time to find out.

The novel opens with the first half of one of those bookends we seldom get anymore but that used to be more common. A port and pipe fueled philosophical conversation between intellectuals discusses the likelihood and possible make up of alternative earths, narrowing down possibilities to one in which the discovery of gunpowder did not occur, but instead psychic powers or witchcraft developed. All three men dream the same dream that night, the content of which is the novel (between the bookends.)

The story occurs in an Alternate European Enlightenment period, on the cusp of the equivalent of the French Revolution. There a suggestions of geographic state overlap and alternative religious and cultural groups (a Jewish people, Germanics, an orthodox church as well as a splinter-group combining attributes of both the more positive standard protestant sects as well as some of the more outr�� practices of some of the less well known splinter groups.

Into this background is thrust the male protagonist, Rodvard Bergelin. Rodvard is an idealist (and naive) clerk, attached to a revolutionary cell. He is tasked with seducing a witch, becoming her paired man, and thus gaining the power of the eponymous Blue Star, which grants him the power to read minds if he has a good look into the eyes of another. Everything proceeds from this one act.

And this is the act that seems to cause the kerfuffle. Let me address it and move on. It is not rape. It is seduction. Roughly done, yes. Boorish, uncommendable. Deplorable, even. The roughness, if continued, might have indeed reached the awful level of rape. That can’t be determined, because ultimately the act was in fact consensual. The female protagonist, the witch-despite-herself Lalette Asterhax, verbally acquiesces, not merely conveying consent through action and body language.

From there the story progresses to betrayals, escapes, reunions, murders, and political intrigue. But what is it really about? Well, there is an awful lot going on. The capacity of custom to rein in power, for one thing. Otherwise, a world in which witchcraft reigned unchecked would necessarily look substantially different that that of Blue Star. I wonder if the hobbled matriarchy is intended to represent a vestigial remnant of an earlier rule by witches in this alternate world? Had there been some brutal, horrific backlash millennia before, an uprising against a ruling class of witches?

The book is about the feet of iron and clay of all men. The idea that even those displaying the noblest of actions may in fact be harboring evil thoughts. That all men do so to some extent; the outer expression — verbal or otherwise — is a mere mask.

It is about the flux and uncertainty involving commitment, second thoughts, infidelity, constancy. The tumble of shifting views and emotions over time.

That good intentions may lead to evil outcomes. At the same time, ignoble, Machiavellian acts may lead to good outcomes. Or may not. Motives may count for little.

The overwhelming nature of a youthful libido, crushing the knowledge of consequences in even the most sensitive, thoughtful, and well-meaning. Rodvard has a relationship with a beautiful, potentially loving witch. Why can’t he corral his wandering eye, we plead with him. But before you judge the wayward affections of Rodvard too harshly, try to recall your own youth. Remember your own actions and the people your actions touched. I like the clean, fragile glass of my house; I won’t be chucking any stones. There is an element of the picaresque about this aspect of the novel, but ultimately the ruminations are too serious, too universal. The bedroom escapades are not played for laughs.

It is about the pot metal beneath the gilding of all high-minded statements and the base drives that override all noble thoughts. It is a hard look at the reality of human nature, the thin veneer of virtue over base, animalistic drives.

The novel traffics in the cynicism of James Branch Cabell, though absent his wry, snarky humor. It is equally as philosophical as Cabell and, from a widely diverging viewpoint, E.R. Eddison.

To be blunt, this isn’t a book I can universally recommend. It isn’t for everyone, and that’s neither a condemnation of the book nor of those who find it unpleasant. Blue Star rewards slow, careful, open-minded reading. This isn’t an action-packed page turner to rocket through. You’ll want to be in the mood for contemplation and have the time for it, whether you concur with the rather pessimistic conclusions or not. If you rush, wondering where the action is, you’ll find this a disappointing read. Happily, I was in the mood for it. But now I’m going to leap into the most recent of Bernard Cornwell’s Richard Sharpe novels. Sabers and rifle bullets, here I come.

May 26, 2024

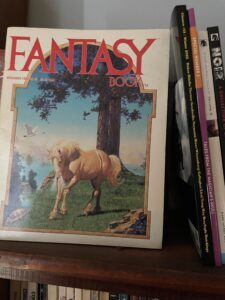

Retro Review: December 1983 “Fantasy Book”

Later today I will be driving MBW, the HA, and myself down to Galveston for the remainder of the Memorial Day weekend. My sister and brother-in-law are driving down from Nebraska to join us. Time constraints thus demand a more abbreviated post, but I trust it will still be worth your reading time.

Fantasy Book was a relatively short-lived magazine, putting out 23 issues between 1981 and 1987. It was one of the first publications I submitted to as a budding teen writer (I hope I never run across any of the manuscripts I wrote back then) so I picked up a copy. I wonder if I still have an ancient rejection letter from Fantasy Book somewhere? I still have the magazine and decided to give it another read after the interval of (oh so many) decades. Here are my brief notes on each story.

Little Axes. Richard Mueller. Two generally unlikeable protagonists encounter a kingdom of Tolkienesque dwarves (note the spelling) in the Pacific Northwest. Slight, moderately entertaining, though implausible. Still, fantasy is the literature of the implausible.

Abraxas. D. Jeffrey Ostling. A slow burn of a horror story, reminiscent of something from The Twilight Zone or Tales from the Dark Side. The composition is a little awkward and the dialogue stiff. But it works okay.

Coco. Don Sakers. A short piece. Part of a larger work? An anecdote? (Too long for a vignette.) An enigma.

Exhibition. Kristine K. Thompson. An orchestral horror story? I failed to grok this one.

Dark Reckoning. Tetti Pinckard. An ambitious weird tale of sex and death.

Wind of Steel. Gene O’Neil. A quiet family drama set in post-war Japan. (Okinawa to be precise, and I know there is a difference.) It is a tale of self-sacrifice, relying heavily upon hints and suggestions. Poignant. Unhurried (perhaps excessively so.)

For the Hell of It. Jefferson P. Swycaffer. The one story I’d retained some recollection of. Was there a reason it had stuck with me? Re-reading informs the answer is “yes.” A medieval army invades Hell itself. Divinely entertaining stuff.

Parameters. Patrice Duvic. A darkly humorous meditation on the nature of change. Science fiction rather than fantasy, the first in a sequence of such in a purported fantasy magazine.

It’s How You Play the Game. Lois Wickstrom. A sci-fi morality tale of some sort? Notable for the conception that text-adventures were the acme of early 80s video gaming technology.

Coyote Awakens. Roger E. Moore. A post-apocalyptic fable featuring the Indian trickster god. There is a humorous Gamma World quality that seems appropriate given the author. Maybe my second favorite story in the magazine.

Godgifu and Aelfgifu. Esther M. Friesner. Lady Godiva meets a fairy. While interesting conceptually, not much was done with it other than a brief moment of “Girl Power.” A fantasy interrupting the string of science-fiction.

The Tempest Within. Jayge Carr. Shapechanging psychic faeries in space!

For a magazine whose cover features a unicorn in a bucolic setting, this issue seemed oddly heavy on dark, horrific stories and science fiction. Interesting in a time capsule sort of way. Overall, few of the stories connect with me now. But the re-read was worth it if only for Swycaffer and Moore’s stories.

If you want to read any of my short fiction, some are available here, here, or even here. And you can check out my Author page for more links.

May 19, 2024

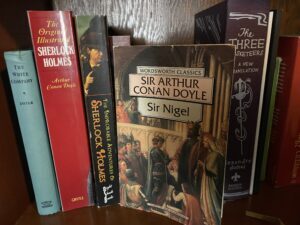

Arthur Conan Doyle’s “Sir Nigel.” Bildungsroman? Prequel? Fun.

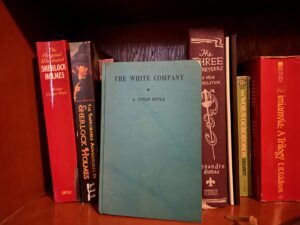

My post last week post reviewed The White Company. Today I’m looking at the subsequent novel, Sir Nigel. Though written about a decade later, the events it relates begin about twenty years prior to those in the White Company. Instead of covering the coming of age and adventures of Alleyne Edricson, we read about the coming of age and adventures of his mentor, Sir Nigel Loring.

As a historical novel it treads much of the same ground, with Doyle discussing church/state relationships, the economics of the Black Death, and providing elaborate and colorful detail concerning clothing, food, and architecture. Perhaps because he was traversing already covered territory, this novel is shorter. It moves much more quickly into the meat of the narrative.

Nigel Loring is a more interesting character than the stock hero Alleyne Edricson. Nigel is a more than a bit Quixotic, raised by his grandmother on a steady diet of knightly romances and chansons de geste. His attitudes are contrasted with those of more pragmatic knights (to varying degrees), with the author staking out no moral position.

The story details Nigel’s relatively impoverished youth, his near disastrous legal disputes with the neighboring Cistercian monastery, and his fateful meetings with his own mentor, Sir Chandos as well as King Edward and the Black Prince. We also get introduced to the archer Samkin Aylward, who accompanies Nigel through many of his adventures. We meet Nigel’s future bride, Mary, who is the instigating motive behind most of Nigel’s chivalrous endeavors during his campaigns in France.

The combat, sieges, shipboard fights, and brutal tourneys are recounted with flair. Doyle doesn’t shrink from the sanguineous, bone-breaking violence. And Nigel isn’t presented as an invincible superhero. He spends long periods convalescing from serious wounds, rather than hopping back into the saddle as if it were “only a flesh wound.”

It is a fun, worthwhile read that expands upon Doyle’s image of the Hundred Years War. It is, I think, a lesser work compared to The White Company. But if you enjoyed that one (and why wouldn’t you?) you’ll probably like Sir Nigel as well.

You might also like my series, Semi-Autos and Sorcery. Go ahead, get your contemporary fantasy/adventure fix.

May 12, 2024

Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The White Company”

Originally serialized in a magazine in the last decade of the 19th century, A. Conan Doyle’s The White Company is damned near perfection. Conan Doyle is known to most as the author of the Sherlock Holmes stories. That would be enough to cement any writer’s reputation as one of the greats. But Doyle wrote prolifically and in a wide variety of genres and styles, including (among others) the Professor Challenger science fiction stories, EA Poe-esque horror stories, and historical fiction. In fact, I’m given to understand that he believed his historical novels were his true legacy. While I hold Holmes in his due, high regard, I’m not going to argue with Mr. A. Conan Doyle. Judging from The White Company, he had good reason to take pride in the works.

Anyone who grew up with Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Howard Pyle will immediately connect with The White Company. It is a distillate of what we loved from Ivanhoe, The Black Arrow, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood and all that ilk. But the book offers more than just an opportunity to wallow in a warm bath of nostalgia. There is a solid adventure tale here. The action is vivid, sometime related at a sort of remove, other times with a blunt force gusto that would have brought a grim smile to Robert E. Howard.

It doesn’t start with a bang. It opens at a rather leisurely pace. Roughly the first half is a sort of cultural travelogue of mid-fourteenth century England as conceived by Arthur Conan Doyle. While it is in many ways awash with the hearkening back to a perceived purer and simpler time that seemed to pervade much of the Victorian Industrial Age fiction, Conan Doyle did not succumb entirely to such a simplistic view. He also included numerous descriptions of the hardship and misery endured by the serfs, especially the French peasants — the Jacques Bonhommes — raided and terrorized by the English free companies and exploited and abused by the French lords. He even manages to squeeze in the economic transition occurring about this time caused by the Black Death, leading to improved standards of living for the peasantry, now able to demand higher wages due to the lessened supply of laborers.

If that sounds boring, I apologize. That’s my fault, not Conan Doyle’s. He introduces his characters, and in following them through the ensuing adventures he shows off the scenery, the typical classes and professions from begging friars, to flagellants, to students, to yeomen, to innkeepers, etc. You’ll be familiar with many of these from The Canterbury Tales. He shows us where they lived and how they dressed, employing a gifted eye for detail, but without the results reading as a series of dry lists or a historical slideshow.

The characters themselves are fun and well-drawn. The hero — Alleyne Edricson — is the expected youth, experiencing the expected trials and rites of passage; meeting a girl, learning to fight, becoming a squire, showing his courage, and facing adventures, travel, and battles. His companions are the gigantic, somewhat dim youth Hordle John and the experienced archer Samkin Aylward. Edricson becomes squire to the knight Sir Nigel Loring (played in my head by David Niven). Each of these men is a unique, fully realized archetype. Nigel Loring in particular, is memorable; which is good since he has his own novel, Sir Nigel, that I intend to read next.

If you haven’t had the pleasure of reading The White Company, I recommend you do so at your earliest opportunity. And I would be remiss if I didn’t take this opportunity of suggesting you also read my Falchion’s Company series, available in print, digital, and audio. Hardly the same thing, of course, but they both contain the word “company” so I couldn’t possibly ignore such marketing felicity.

May 5, 2024

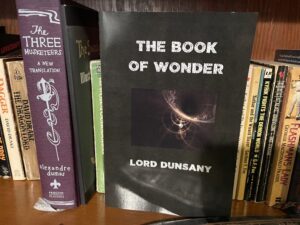

Lord Dunsany’s Book of Wonder

This collection of short stories by Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, aka Lord Dunsany, is akin to a jewel box. Each story is a brilliant, faceted gem to be enjoyed for its color, sparkle, and luster. These are not lengthy tales. These are snippets, anecdotes, oneiric snapshots of dreamscapes. It there is a throughline or theme it is the comeuppance of thieves and pilferers. But primarily it is, as the title has it, a Book of Wonder. Following are my (appropriately brief) comments on each entry.

The Bride of the Man-Horse. A fanciful romance of joy and beauty, brief and lyrical.

The Distressing Tale of Thangobrind the Jeweler. Read before and reviewed here.

The House of the Sphinx. Enigmatic and evocative anecdote. Dunsany seems here to be tapping into Poe and Lovecraft across the nighted shores of time.

The Probable Adventure of the Three Literary Men. More musings on the unwisdom of thieving from great and terrible powers. Dunsany seems to have written much of this with a half-smile and tongue thrust deeply in his cheek. The sparse descriptions hint at so much yet reveal so little.

The Injudicious Prayers of Pombo the Idolator. Of the unwisdom of both excessive godsbothering and excessive impiety. Perhaps a warning to pursue moderation and eschew immoderate obsession. If one persists in pestering a passel of petty divinities, one is advised to practice the proper protocols.

The Loot of Bombarasharna. High seas adventure. Or, rather, the aftermath of prior adventures plus one last job. There is an almost Mark Twain-esque aspect to the telling: droll yet ultimately melancholy.

Miss Cubidge and the Dragon of Romance. An Edwardian fantasy, perhaps. Or maybe a description of a descent into delusion and madness. Either way, it is a lovely dream.

The Quest of the Queen’s Tears. A fair tale. Cautionary? Tragic? Semi-autobiographical? I cannot say. It does, however, constitute one of the more straightforward narratives in the collection.

The Hoard of the Gibbelins. A classic, reviewed here.

How Nuth Would have Practiced His Art Upon the Gnoles. A recounting of an attempted heist, featuring another of Dunsany’s burglars. Sort of a companion piece to The Distressing Tale… and Hoard of the Gibbelins.

How One Came, As Was Foretold, to the City of Never. An elevated sort of Little Nemo in Slumberland. Wonder tinged with regret and a twist that — while unexpected — supplies the perfect touch.

The Coronation of Mr. Thomas Shap. Of lucid dreaming and overreaching. Reality rears its pitiless head here in the Book of Wonder.

Chu-Bu and Sheemish. Always amusing. Reviewed here.

The Wonderful Window. A bittersweet, voyeuristic tale. It feels as if it must be illustrative of some epigram or axiom.

So, should you read this? Absolutely. But don’t hurry through it. Take out one gem at at a time, watch the light play through it. Savor its beauty along with a glass of your favorite beverage. An aged whiskey. A barley wine. A tawny port. Trust me, it will pair well.

Speaking of pairing books and booze, crack open a cold one and accompany it with — oh, pretty much anything I’ve written. I mean honestly, beer goes with everything. But, how about Reunion?

April 28, 2024

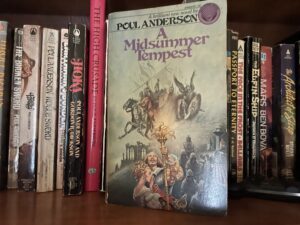

Poul Anderson’s Magnificent “A Midsummer Tempest.”

1974’s A Midsummer Tempest exhibits an artist working at the height of his powers. It is a work that defies clear categorization. Poul Anderson has created something utterly indiosyncratic that nonetheless depends entirely upon prior works.

The tale occurs near the culmination of the English Civil War. So, it is historical fiction then, right? Not so fast. The world of AMT is one in which the plays of William Shakespeare are accurate histories. All of them. (As are one or two other works of fiction, apparently. Watch for cameos.) As if that was not enough, it is also a world in which the Industrial Revolution has begun early. Anderson thus cleverly constructs a backdrop of Progress versus Poetry, Science versus Romance.

Against this background, Prince Rupert of the Rhine — with the aid of Oberon and Titania — quests to recover Prospero’s broken staff and sunken grimoire in order to prevent the defeat of Charles I.

While fun and involving, the plot is secondary to the telling. The language is deliberately florid, the dialogue flows in near seamless Iambic Pentameter. It is pure artistry.

If you read my post on Anderson’s short story collection Fantasy, you might recall the story House Rule. The Old Phoenix makes a reappearance in AMT. Anderson indulges himself (in a fashion similar to Robert Heinlein and Stephen King) by using the transdimensional tavern to allow some of his characters from other books to meet each other. It is charming and fun, though in other hands it could be an eye-rolling conceit. (The Old Phoenix shows up again in the Epilogue. Watch for more cameos. See how many you can recognize.)

Will Fairweather is a standout character, written (or so I assume) as an homage to Shakespearean earthy characters such as Dogberry. Anderson has tremendous fun with Fairweather’s sexual puns and innuendos, his dialogue written in dialect.

Contrary to the blurb on the back cover, AMT is not Sword and Sorcery. It isn’t a breakneck page turner, not action heavy. That isn’t to say it is either bloodless or dull. There is plenty of adventure, combat, escapes, and thrills. But it is a book to be savored, not rushed through. The depth, layers of meaning, and beautiful descriptive passages should be lingered over. If, like me, you appreciate John Myers Myers’ Silverlock and E.R.R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros, AMT will occupy a cherished spot on your shelves.

Perhaps a bit of counterprogramming is called for in the commercial portion of today’s post. If you are in the mood for something rather more gritty and grounded in your fantasy, after the gorgeous flight of fancy of AMT, pick up a copy of my Thick As Thieves, my S&S homage to Elmore Leonard’s crime novels.

April 21, 2024

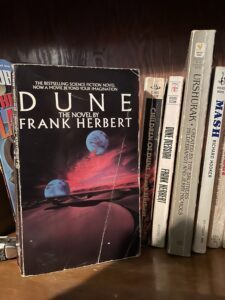

Science Fiction’s Top Five Tough Guys

Most everyone loves the fictional tough guy: the battle-hardened enforcer as quick with his fists as he is with a wry comment. He’s usually not the primary hero. Instead he’s Little John, not Robin Hood; T.C., not Thomas Magnum; Tars Tarkas, not John Carter. ��The hero is usually the swashbuckling, more vulnerable, romantic lead. But he depends on the big bruiser. And vicariously, so do we.

Science fiction offers some prime examples of this archetype. ��Here are my top five.

Amos Burton, The Expanse. One of the more complete, complex examples of the type. Burton’s damaged psychological make up provides him more depth than most. Though Wes Chatham, the actor portraying the character in the television series, doesn’t look like the character as described in the novels, he embodies the essence as near perfectly as one could wish. If you want someone at your back, the self-proclaimed “last man standing” wouldn’t be a bad option.

Jayne Cobb, Firefly. The hero of Canton provides all the muscle and firepower you’d want backing you up — so long as you could trust him at your back. Adam Baldwin (and, of course, good writing) provided dimension to what could have been a flat stereotype in other hands.

Duncan Idaho, Dune. Loyal, self-sacrificing. You can understand why one might want to keep him around. Even after death. Again and again.

John Stark, The Book of Skaith, et al. So, sometimes the primary hero is the tough guy. If I make the rules, I can bend the rules. Big, strong, and fast (evoking comparison with Conan of Cimmerian) Stark is his own enforcer.

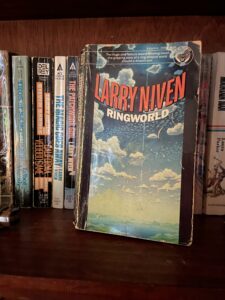

Speaker-To-Animals, Ringworld. As suggested by the reference to Tars Tarkas, the tough guy doesn’t have to be human. I suppose I could have gone with Chewbacca here, but I prefer someone who delivers understandable dialogue.

These are my five. Whom am I missing? Which sci-fi tough guys would you suggest, and whom of my five would you replace?

In the spirit of John Stark — that is tough guy and hero in one package — today I’ll promote Karl Thorson of my Semi-Autos and Sorcery series.��Try the stories for yourself, see how he stacks up. If I may quote a reviewer, “Karl Thorson is a supernatural Jack Reacher. That’s a good thing.” (Hat tip to Mr. Troy Osgood.)

April 14, 2024

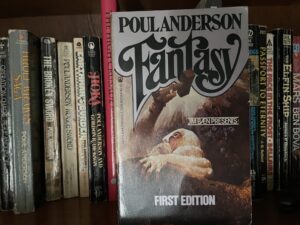

Poul Anderson’s “Fantasy.” A Showcase.

In 1981, Poul Anderson put out a collection of selections of his fantasy short stories, titled plainly enough Fantasy. Though perhaps that’s misleading, as not every entry is a fantasy short story, some being essays, some humorous oddities, and some defying the reader to apply classification. But that, I believe, was intentional in order to spotlight the breadth of the subject matter.

Is it any good? Well, of course. Poul Anderson wrote this stuff. Let’s take a deeper look. Advance warning: much of this I have read and reviewed before. Links abound.

House Rule. I am drawn to stories that take place in taverns. Taverns frequented by the fantastical or those time/dimension jumping taverns that are themselves fantastical, it doesn’t much matter. Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon. Gavagan’s Bar. Etc. The White Horse in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman��offered a kindred drinking establishment to that in Anderson’s tale here. While I like House Rule, it is more of an anecdote than a complete story. Still, I’ll take what is poured until the bartender gets around to serving me again. (Which should be during A Midsummer Tempest, in my TBR pile.)

The Tale of Hauk. I wonder how many books I have reprinting this one. I reviewed it here.

Of PIGS and MEN. Tongue-in-cheek historical revisionism I previously reviewed here.

A Logical Conclusion. I remember liking this one when I reviewed it here. It holds up.

The Valor of Captain Varra. Always good to encounter one of the prototypical fantasy bards again. I reviewed it here.

The Gate of the Flying Knives. Revisiting Sanctuary after many years. And two of Sanctuary’s more anomalous, short-term denizens: Cappan Varra and Jaime the Red who both apparently return to their respective universes. A fun story, despite Cappan Varra feeling to me vaguely out of place in the stinking riot that is Sanctuary. He classes up the Vulgar Unicorn, which doesn’t seem quite right.

The Barbarian. Anderson has some fun with Robert E. Howard’s Hyborean Age conceit. Anderson is underrated as a humorist, subtly droll and tongue-in-cheek. He tells a sort of porto Groo the Wanderer story. Some REH readers might bristle, but I believe Anderson is poking gentle fun at the worst of the Clonans, rather than at the Ur-barbarian himself. Indeed, in the very next entry in this collection he writes “Howard could make Conan’s accession quite plausible.” (Page 166.) And Anderson wrote a Conan pastiche, Conan the Rebel.

On Thud and Blunder. Seminal, indispensable resource for writers of heroic fantasy. Reviewed here, though I honestly didn’t provide more than the written equivalent of a thumbs up. The thing is, if you write this sort of thing, Anderson has some advice for you. Good advice, if you want my opinion, though some of his observations should be considered in light of more current research (such as the quality of European swords.)

Interlopers. A fantasy-tinged science fiction story. The conceit is relatively easy to discern early on. Those who have read Broken Sword will pass through familiar territory. In some places it reflects Anderson’s early, less mature political philosophy. Overall, the weakest entry so far. Which still leaves it better than 90% of speculative fiction shorts.

Pact. A humorous riff on The Devil and Daniel Webster with a nod to Captain Stormfield’s Visit to Heaven. At its length, the story should have dragged. Bit it did not, Anderson skillfully keeping it light and zipping along.

Superstition. A post-apocalyptic fantasy about correlation and causation. Not bad, but not my favorite.

Fantasy in the Age of Science. An essay concerning the nature of fantasy (and science fiction, though primarily focused on the former) in the context of the (then) modern era. Anderson keeps if from becoming dryly academic and makes some trenchant points.

The Visitor. A poignant ghost story, dressed up with bookends of ESP and pseudo-scientific psychic phenomena. Poetic, elegiac.

Bullwinch’s Mythology. Amusing description of a mid-20th Century American pantheon of gods from the viewpoint of a mythologist writing millennia in the future.

Afterword. Worth reading, but unnecessary for appreciation of the collection.

Fantasy is a hefty, eclectic volume. It is one I should have picked up years ago. Well, I have a copy now. If you are feeling acquisitive, I suggest picking up something of mine. I think you’d enjoy the Semi-Autos and Sorcery series.