Ken Lizzi's Blog, page 4

March 16, 2025

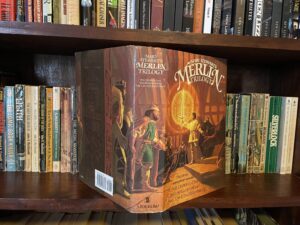

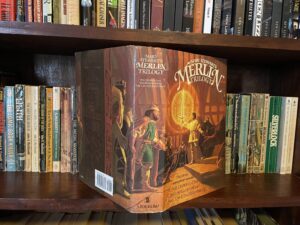

Mary Stewart’s The Merlin Trilogy Re-Read Part II: The Hollow Hills

Given the nature of telling a well-known story through the eyes of a character with foreknowledge, it is unsurprising that The Hollow Hills is generally lacking in suspense. We readers — even more than the narrator, Merlin — know the broad brush strokes of what is going to happen. The fun comes from the variations, from Stewart’s refashioning Geoffrey of Monmouth’s improbable legend into a plausible narrative. And, as with Book I, The Crystal Cave, much of the enjoyment comes from the Easter Egg hunt. Reading closely for Stewart’s laying of eggs to be hatched later on — whether in the current book or the next — adds a layer of entertainment for those of us who have consumed innumerable takes on the Matter of Britain.

The Hollow Hills covers the period from Arthur’s birth to his ascension to the throne. Given that there is little in the way of mythical material concerning this time of Arthur’s life, Stewart — like T.H. White before her — has nearly a blank canvass on which to create. Much of this she spends creating a career and educational path for Merlin, following him to Asia Minor. There is good color here and I enjoyed it. Once Merlin returns to Britain, events speed up and we get Stewart’s take on the whole sword-in-the-stone business. It’s good stuff.

An aside: I wonder if some of Merlin’s prognostication and references to the rise and eventual fall of the island kingdom is a veiled reference to the then relatively recent loss of empire. Or am I reading into the book something that wasn’t written? Subtext can be an illusive — or even absent — thing.

The obligatory self-promotion follows: Please buy one of my books. Thank you.

March 9, 2025

The Web Log is Busy

March 2, 2025

An Unconventional Convention

MBW, the HA, and I packed into the car on Thursday and headed northeast. Destination: ConFinement VI. We reached Louisiana by mid-morning and hit Mississippi by the afternoon. I didn’t want to subject the family to a thirteen hour run, so holed up for the night at roughly the midway point: Hattiesburg, MS. We had dinner at Southern Prohibition. The beer was quite good, the food tolerable (though the Brussels Sprouts were outstanding) but this was one of those establishments that wants you to order through your phone and pay by ApplePay. Points off for that.

We reached Lebanon, TN the next afternoon in time for the con to begin. ConFinement is Mad Mike Williamson’s baby, now in its sixth year. It is a small gathering, with almost all the panels occurring in the same space, one after another. There is a small vendor’s room, and a hospitality suite. (I contributed a bottle of Tullamore DEW which did not survive the first night.)

I was on one of the first panels, Sword-and-Sorcery 101. After a bit of rough start it picked up and went, I believe, reasonably well. I had a reading the next day. Other than that, I was at loose ends, drifting, dropping in on panels, or just chatting. I also sold quite a number of books. (Thanks to all of you who bought a copy of my scribblings. I wish you happy reading.) Glenn Reynolds of Instapundit was the guest of honor. Sarah Hoyt, the previous year’s GOH was again in attendance, as were many familiar faces from previous years.

MBW and the HA drove in to Nashville for a bit of sight seeing, then returned to the hotel for some pool time. Saturday we had dinner at Tenn Lakes brewing. The beer didn’t live up to SoPro, but the food was excellent, notably the smoked wings.

Today we need to pack up and hit the road. We’ll be going back via a different route. Tonight’s destination: Little Rock, Arkansas. Might as well see a bit of the country, right?

The morning is getting on, so I will cut this short with just the usual hucksterism. My books are available for purchase. Take a look at the offerings on Amazon, treat yourself to a spot of two-fisted fabulism.

February 23, 2025

The Merlin Trilogy Reread Part I: The Crystal Cave

I picked up this collected edition of Mary Stewart’s Merlin Trilogy only in part because of the oddly endearing, but perhaps misleading Hildebrandt Bros. cover. The other reason was, I suppose, a form of nostalgia. Allow me to explain.

When I was in sixth grade, both my mother and my step father were working. No one was able to pick me up after school. (I attended small private schools, with a couple of brief interludes in public school, up until college. So, no school bus.) After school, I walked a couple of miles to the nearest public library and stayed there until around six when my mother came to collect me. (This was in the eighties. No one pitched a fit upon seeing an unaccompanied twelve year old. And yes, we did ride in the back of pickup trucks and drink from the garden hose and ride our bikes for miles so long as we were home for supper.) In retrospect, this might have been the happiest year of my life. It was certainly the most formative. I got to spend over two hours every day in the library, reading whatever I wanted, without interruption.

The partial basement level housed the novels:science fiction and fantasy, historical novels, adventure, etc., though the classics were upstairs for some reason. The point is, that eventually I got to Mary Stewart. And I was enthralled, devouring all three as fast as I could, which was pretty fast. (When did I lose that speed?) When I ran across this collection, I had to buy it in order to discover if the magic remained.

I’ve finished the first book, The Crystal Cave. I am fairly certain that much of it flew right over the head of twelve-year old Ken during that initial reading so long ago. I’m not referring only to the more prurient bits (which I did not in the least recall) but which Stewart handled with a certain refined euphemistic artifice. At twelve, I hadn’t yet consumed the sheer volume of books on The Matter of Britain that I have since read. I may have already read Rosemary Sutcliff’s Sword At Sunset, and perhaps Gillian Bradshaw’s Hawk of May. But I hadn’t yet absorbed the sheer mass of Arthurian legend to allow me to grasp the allusions Stewart larded the story with, the seeds of foreshadowing she sowed. I was reading it purely as a novel. This time I read it more like a detective, noting clues.

So, did it hold up? Is the enchantment still in place? Well, I don’t think that is entirely possible. I can’t, at 55, undergo the same experience I enjoyed at 12. Instead I appreciated it on another level, admiring the craft and trying to keep up with the author as she laid the foundation for the advent of Arthur. Telling the story entirely through the first-person viewpoint of Merlin as Stewart does, some of the more exciting aspects that impelled a younger Ken to gravitate toward every piece of Arthurian literature he could find are necessarily absent or elided. But Stewart makes up for that in providing a convincing magician, giving the reader access to his unique perspective; sort of above the fray, possessing a generational outlook rather than concerned solely with the hurly-burly of the day.

I’m eager to get on to the next book.

If you are eager to get straight to some reading, why not something of mine? The four-volume collection of Semi-Autos and Sorcery perhaps. Or maybe you’re in the mood for a sword-and-sorcery/crime mashup such as Thick As Thieves.

By the way, if you happen to be in the Nashville area February 28-March 2, I’ll be a panelist at ConFinement VI. Come by and say hello.

February 16, 2025

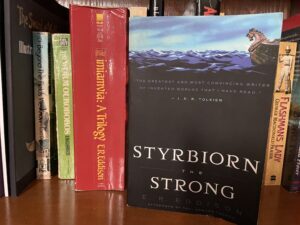

Styrbiorn the Strong. Eddison Breathes the Northern Thing.

E.R. Eddison is known primarily for The Worm Ouroboros, and to a lesser extent the Zimiamvia Trilogy. But he also wrote a historical novel. As a youth he fell under the eddic spell of the Norse sagas (e.g., The Elder Edda.) And why wouldn’t he? The sparse, barebones recitations of blood feuds, raids, treachery, and murder couldn’t help but appeal to an imaginative boy’s spirit. Styrbiorn the Strong, published a mere four years after the successful release of Worm, was Eddison’s expression of his love for the tales, moderated through his poetic gifts as a novelist. He did not produce a work of pastiche or scholarly recreation. As he states in the Afterword of Syrbiorn, “My story is not an imitation of a Saga. I have told it in my own way. Imitations are dead lumber: but having been a reader of Sagas these twenty-five years, and having chosen such a theme and staged it in such an age, I should be foolish to deny that while the defects of this book may be mine, its merits, if it has any, must be fastened on that spirit which lives in the Sagas.”

And with that intention in mind, he wrote a historical novel inspired by a couple of fragments which referenced a character named Styrbiorn the Strong. He cleaved to as much of the historical record as he could, peopled his dramatis personae with actual characters and/or those found in the sagas, and produced a historical novel. Yet not one readers of historical novels would expect. He did not filter the story through the mores and preconceptions of early 20th Century Englishmen. While he did not limit himself to the skeletal narrative of a narrative, neither did he flesh it out in topcoat and top hat, merely providing a bit of muscle and sinew and a hint of flesh. The “spirit of the North” (again quoting from the Afterword) comes through clearly in the lack of authorial judgment. The characters act, but no moral accusations are intimated, no aspersions cast either directly or indirectly. The reader is left to consider such matters for himself.

The story is, as anyone with even a passing familiarity with the sagas would expect, a tragedy. Styrbiorn is clearly headed for an early grave, given his intractable, self-willed behavior; an attitude bordering on hubris. He is of a mold as Sampson or Beowulf, almost supernaturally strong. Surrounded by fatalistic, violence prone Vikings, the only real question is what will trigger the ultimate doom. This being Eddison, the answer is, of course, a beautiful, strong-willed woman.

The characters do possess a certain similarity to those of Worm and Zimiamvia. Eddison admires those above the common herd. The exception are not — in his view — beholden to morality, conventional or otherwise. But Sytrbiorn is unlike the more typical Eddison hero in his flaws, his stuttering and rather linear, non-Machiavellian mind. But he is nonetheless a fascinating character to follow through the latter years of the Viking Age, which Eddison limns with his customary skill. Styrbiorn’s particular friend Biorn is a skald. Eddison’s depiction of a mead hall celebration and the poetry (adapted by Eddison from the original) that he places in the mouth of Biorn is one of the most evocative scenes I’ve ever read. I felt I was a blink away from finding myself there. The power of words does not reach much higher than that.

Despite the foregone, inescapable conclusion, Eddison manages to maintain a level of suspense. The actual end does offer a degree of the unexpected. And the denouement is moving and goes some way to nudging the novel from historical fiction into the realm of fantasy. For anyone with more than a passing interest in the Northern Thing, I recommend picking up a copy of Styrbiorn the Strong.

I also recommend picking up a copy of the four-volume collection of Semi-Autos and Sorcery. Karl Thorson wouldn’t have felt out of place swinging an axe in the shield wall beside Styrbiorn.

February 9, 2025

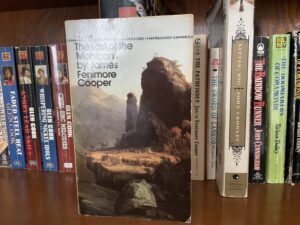

The Last of the Mohicans: Part of the DNA of American Fiction

While reading my copy of James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans I found between the pages a bank deposit slip of mine from 1986. So I know I must have read this copy before — the binding shows some wear — or at least reached about the midpoint and left a book marker there. But my memory of the contents is limited. The truth is, I read it through the lens of the 1992 film, curious to observe the deviations, of which there are many. In fact the Daniel Day-Lewis vehicle is pretty much all deviation, although a damn fine flick.

Despite the fact that the events printed in 374 pages of paperback could have been condensed to about a third that amount, I thought the story held up well. In fact, I think the story held up so well that it continued to influence American fiction at least through the mid-20th Century. Samuel Clemens may have derided Fenimore Cooper, but there’s no denying he read him.

The Last of the Mohicans is the second (chronologically) of the Leather Stocking Tales, though the third published. On my shelf (still, I believe, unread after decades of gathering dust) is The Pathfinder, the fifth published, but the third chronologically. I am listening to The Deerslayer, the first chronologically, though the fifth (and last) in publication order. The Leather Stocking Tales recount the life and exploits of Nathaniel (Natty) Bumppo, aka The Deerslayer, Hawkeye, La Longue Carabine, etc. He is a distinctive character, the Ur-American frontiersman.

Hawkeye, and the Leather Stocking Tales continued to influence American writers for hundreds of years. Or that’s how I see it. Natty Bumppo makes an appearance in the vast forest of the Commonwealth of Letters in John Myers Myers’ essential, don’t-miss novel Silverlock . I can’t help but see the fingerprints of Fenimore Cooper in Robert E. Howard’s Beyond the Black River. Replace Natty Bumppo with Conan, the Huron’s with the Picts, the English fort with the Aquilonian. No, there is no strict one for one analogue in any of the elements, but the works do resonate harmoniously with each other. The literary heredity seems clear to me. Louis L’Amour, in his Sackett novels, references Fenimore Cooper’s work, having one of the Sacketts (William Tell Sackett, if my memory serves) comment positively on one of the novels. (I can’t help but wonder how much of L’Amour’s depiction of Indians derived in some form or another from Cooper’s descriptions of the methods, mores, and habits of the Northeastern tribes. And I also wonder about Cooper’s accuracy from a historical and anthropological view. But I’m straying from my thesis.)

Look, I won’t lie to you. The dense descriptiveness, the prolix redundancy, the soliloquies, and all the other baggage of early nineteenth century literature did slightly hinder my enjoyment of what is, at its heart, a taut, tragic adventure tale. But that heart remains. I’m at the midpoint of The Deerslayer. If I can judge the rest of the series from this perspective, I’d hazard that they are all variations on the same story. So I rather doubt I’ll read all five novels. But I don’t regret having spent time with Mr. Cooper. And I’d wager that a second hand, third hand, or at even further remove, I’ve spent much more time with him. As you probably have as well.

Before you jump right into the Leather Stocking Tales, why not give something of mine a try? The Semi-Autos and Sorcery series is a book shy of Cooper’s pentalogy, but don’t let that stop you.

February 2, 2025

Near Term Event: ConFinement VI

I will be attending ConFinement VI, February 28-March 2. I’m scheduled for a panel on Friday. We’ll see if I’ll sit in on any others. If any readers are the Nashville, TN area that weekend, see if you can grab a membership. Drop by and say hello.

ConFinement is a small gathering of — primarily — science fiction and fantasy authors, held in Lebanon, TN, about thirty minutes east of Nashville. The panels are rather more casual and intimate than in the usual convention setting. There is a small dealers room, some gaming, and a hospitality room that is conducive to some fascinating (often hilarious) conversations late in the evening.

I will be bringing MBW and the HA this year, taking a couple of days for the drive. The HA will likely spend as much time as possible in the hotel swimming pool. But I think MBW will want to take the car into Nashville for a bit of exploring. So the HA will have to remain dry for some of the trip.

If you feel like contributing some gas money, why not buy a book? People do seem to like them. Mostly; you can’t please everyone.

January 26, 2025

Technical Difficulties

The Web Log is experiencing technical difficulties. Please check back next week for something more entertaining than this boring note.

January 19, 2025

January Update

To anyone looking it might not appear that I’m doing any writing. But I am. The staring at the walls or spending entirely too long in the shower phase is often an essential component of the writing process. I’m not going to discuss what I have in mind; it is too early. If I crack the story, however, this one should occupy me for most of the year.

I also have completed projects waiting for responses from publishers. So, we’ll see.

Meanwhile I am reading. Currently I am reading — or re-reading, I’m not entirely sure which — The Last of the Mohicans. I’ve had the book on my shelves for decades. It was, I believe, a Christmas present in my youth. The condition of the binding suggests it has been read at least once, but that could merely be age. So far, so good, though I do grasp the foundation for Mark Twain’s mockery “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses.”

In the car and at the gym I am listening to Operation Pineapple Express. It is intense. I find myself wondering which of the multiple storylines will be excised in the inevitable movie version.

Well, I have some more mulling to do, and those walls won’t stare at themselves.

If you’d like to occupy yourself with something rather more entertaining, pick up the collected four book series Semi-Autos and Sorcery.

January 12, 2025

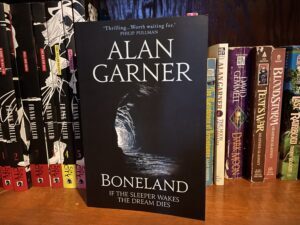

Fifty Years Later: “Boneland.”

A few months back I read Alan Garner’s The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath, both of which I considered here. In 2012, some fifty years after the original two-thirds of the Weirdstone Trilogy (or the Tales of Alderly), Garner released Boneland. I won’t say it is the concluding volume of the trilogy. That may be a trifle confusing. Let me try to explain.

The first two books fit neatly into Young Adult territory, or were, perhaps, Juveniles, (e.g., The Chronicles of Narnia, The Dark is Rising, etc.) Fifty years later Garner could not, or would not, return to the world he’d created with the same approach. For whatever reason, he did not write another YA or Juvenile novel. He instead chose to focus on one of the twins (Colin) as an adult. And the book is written by a man with fifty more years under his belt, a writer with other interests and something different to say. Boneland is not, therefore, a continuation of the narrative; it does not pick up where Gomrath left off.

Not only is there a narrative breach, there is a fundamental tonal breach. Do not open Boneland expecting to encounter dwarfs, wizards, witches, and plucky youths pursing adventure. This is an entirely different story, a frequently internalized, psychological story. In short, you have to be in the mood for it. Garner’s prose, trimmed to the bone, demands a lot from the reader. He does not take the reader by the hand and lead him through the tale. Instead he leaves it to the reader to decipher what exactly is happening, what is real, what is imagined, and what is perhaps some juxtaposition of the two.

Now, I’m not always in the mood for that. Sometimes I simply want to be told a story, not be expected to puzzle out the events or meanings. Happily for me, I was in the frame of mind for the challenge. (Yes, I think “challenge” is the right word.) Colin (decades after his sister Susan disappears) is now a polymath, employed as an astrophysicist attached to a radio-telescope project; a project Colin has apparently manipulated to search the Pleiades for some contact with Susan. But this is never entirely spelled out. Instead, the reader is left to consider if the events Colin experiences are in fact hallucinations or manifestations of mental illness. Much of the narrative involves Colin’s interactions with his therapist, Meg, who may or may not have some connection to the events of the first two books, and who may either be inimical to Colin or entirely on his side. There is also, seemingly, another, unnamed narrator from the deep, deep past involved in a parallel quest of ritual magic — a quest that may be read as convergent rather than parallel. Garner seems no longer interested in local folklore, or even Pan-European myth. He is dealing with more fundamental, universal themes, reaching back to the dawn of mankind (and, in fact, even further.) He is dealing with the intersection of faith and science, with the power of story and belief to influence reality (or at least the perception of reality.)

And he is fully committed to ambiguity.

That, I think, is the theme or message of the work. Ambiguity. That the knowledge of uncertainty is the only true certainty. Anyway, that’s what I got from it. Admittedly I may have entirely missed the point. Still, I appreciated it, though I am self-aware enough to realize that had I read it at some other time I would have been either bored with the book or irritated by it.

I hope never to bore with any of my tales of two-fisted fantasy. Try some for yourself.