Andrew Skurka's Blog, page 17

May 13, 2020

Encouraging sign: Rocky Mountain to reopen May 27

Rocky Mountain National Park announced yesterday that they will begin a phased reopening starting on May 27. The press release is here.

Most relevant to this readership, backcountry camping will be permitted right away, and will continue through the fall as normal.

Even though Rocky is a National Park, the release points out that under Colorado’s current “Safer at Home” policy, travel more than ten miles from your home and/or into the mountain towns is discouraged. The opening of the park seems inconsistent with this safer-at-home order, which makes me wonder: Do NPS officials foolishly believe that non-locals won’t visit the park, or does the reopening align with the expected expiry of the 10-mile recommendation (which seems untenable for much longer since our high country will open up next month or summer recreation)?

Rocky is the third most visited unit (with 4.5 million visitors, behind only the Smokes and Grand Canyon); it’s one-tenth the size of Yellowstone; and two small towns on its east and west sides serve as its main access points. I’m uncertain how NPS solved for social distancing requirements and addressed concerns about medical care in rural areas, but I’m going to assume that officials in DC and in both Larimer and Grand counties signed off on it.

It’s an especially encouraging sign that Rocky has scheduled a reopen date, and I hope that other parks will soon follow. The park experience needs to be different in 2020 to accommodate the risk of Covid-19, but parks do not need to remain closed.

The post Encouraging sign: Rocky Mountain to reopen May 27 appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

May 11, 2020

Tutorial: Plan a backpacking trip in these 7 steps

This year I will plan twenty-nine backpacking trips. They are scheduled June through October, run three to seven days, and are scattered throughout North America in the high desert, eastern woodlands, mountain West, and Alaska.

In addition, I will also ready our 240+ clients, who are of mixed ages, genders, fitness, and experience.

To pull this off efficiently and without mistakes, over the years I’ve developed a planning framework that works for any trip and that can be used by any backpacker.

7 steps to plan a backpacking trip

The process goes like this:

Define the trip parameters: Where, when, with who, and why? Research the conditions, like temperatures and bug pressure. Select gear that is appropriate for the parameters and conditions. Plan snacks and meals. Collect or create navigational resources like maps and guidebooks. Gain the requisite skills and fitness for the itinerary. And, Complete a final systems check just before hitting the trail.

Let me go into more details.

Looking north over Arapaho Pass and Lake Dorothy towards Apache Peak, Lost Tribe Lakes, and the west ridge of Lone Eagle Cirque

Looking north over Arapaho Pass and Lake Dorothy towards Apache Peak, Lost Tribe Lakes, and the west ridge of Lone Eagle Cirque1. Define the parameters

The “Five W’s” is a journalistic device, but it’s also a good starting point for trip planning. I don’t need definitive answers to every question right away, but I want to start narrowing my options.

Start with these questions:

Where?When? Why, in terms of hiking versus camping?

Then add more specifics:

What length of time?What specific trails, routes, landmarks, or campsites?How many miles or how much vertical?Who else will join me, if anyone?

Also, consider the logistics:

Do I need permits? If so, how, when, and where?How will I get there and back?Are there unique or notable land use regulations or requirements?

I take all these details and drop them into a “Trip Planner” document that serves as a “parking garage” of information and that can be shared with my emergency contacts just before I leave.

2. Research the conditions

Once I have a reasonably defined trip plan, I start researching the conditions that I will likely encounter so that I can prepare properly, mitigate risks, and rule out baseless “what if” and “just in case” scenarios.

I’m only interested in conditions that will influence my selection of gear and supplies, or that will demand particular skills. I look at:

ClimateDaylightFootingVegetationNavigational aidsSun exposureWater availabilityWildlife & insectsRemotenessNatural hazards

For more details on this step, read this post.

I compile the findings of my research in a separate document, and I cite my sources so that I can easily re-find them if I find contradictory information elsewhere.

In a downpour, would you rather be relying on just a rain shell, or a rain shell plus an umbrella?

In a downpour, would you rather be relying on just a rain shell, or a rain shell plus an umbrella?3. Select your gear

For a beginner backpacker, the task of gear selection is usually the most time-consuming, certainly the most expensive, and unfortunately also the most frustrating — it’s very easy to go down the rabbit hole here.

To make this process easier for our clients, I give them:

A time-tested and well designed gear list template;Examples of completed gear lists for similar trips; and,A copy of The Ultimate Hiker’s Gear Guide .

These resources help direct their attention and cut through the noise.

Clients also have email access to their guides and their group, so that they can get advice specific to them. If you don’t have an immediate contact who really knows their stuff, utilize a community forum like r/Ultralight.

Clothing, footwear, and a few other items for the winter months of my Alaska-Yukon Expedition

Clothing, footwear, and a few other items for the winter months of my Alaska-Yukon Expedition4. Plan your food

We’re vulnerable to “packing our fears.” If we fear being cold at night, we bring a sleeping bag that’s excessively warm. If we fear bears, we sleep in a full-sided tent (which won’t help but may make us feel better). And if we fear being hungry, we pack too much food.

I’ve given in-depth meal planning recommendations before (read this or the food chapter in my Gear Guide), so here I’ll provide some basic pointers:

Plan for 2,250 to 2,750 calories per day, or 18 to 22 ounces assuming an average caloric density of 125 calories per ounce.If you’re older, female, petite, or on a low-intensity trip, go with the low end of this range. If the opposite is true, go with the high end.Variety is the spice of life, so pack foods with varying tastes (spicy, sweet, salty, sour) and textures (chewy, crunchy).Early on in a trip, treat yourself with real food — like a ham sandwich, avocado, or apple — that will also delay on the onset of culinary boredom.

For breakfasts and dinners, try these field-tested options, instead of spending your hard-earned money on exorbitant freeze-dried meals or punishing yourself with thru-hiker fare like Ramen noodles or Lipton Sides.

Food for a 9-day yo-yo of the Pfiffner Traverse. Six days fit in my BV500, and I ate through the “overflow” prior to entering Rocky Mountain National Park where the canister is required.

Food for a 9-day yo-yo of the Pfiffner Traverse. Six days fit in my BV500, and I ate through the “overflow” prior to entering Rocky Mountain National Park where the canister is required.5. Create or collect navigational resources

For my earliest hikes, I utilized whatever resources were conveniently available and that seemed sufficient. Before thru-hiking the Appalachian Trail in 2002, for example, I purchased the ATC Data Book and downloaded the ALDHA Thru-Hikers Companion. And to explore Colorado’s Front Range the following summer, I bought a few National Geographic Trails Illustrated maps that covered the area.

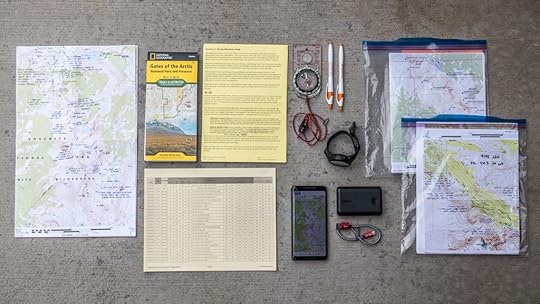

But when I started adventuring off the beaten path, I had to create some or all of these materials from scratch. Through this process, I developed what I believe to be an optimal system of maps and resources that includes:

Large-scale paper topographic maps,Small-scale paper topographic maps,Digital maps downloaded to a GPS smartphone app,Route description and tips, and possiblyA datasheet, which is a list of key landmarks and distance along a prescribed trail or route.

A complete navigation system

A complete navigation system6. Gain fitness and skills

There’s no better way to gain hiking fitness than by hiking!

And there’s no better way to develop backpacking skills than by backpacking!

But who has the time and ability to do that? Not me, and probably not you.

The next-best option is to:

Workout more intensely, to maximize the potential of the time you have available. Personally, I run 60-70 miles per week. Alan Dixon has a training plan that’s more hiking-oriented and probably more realistic.Read and watch skill tutorials, such as my series on navigation, pooping in the woods, finding great campsites, packing your backpack, and knot-tying.

A low-risk “shakeout” is also very valuable. It can be done locally, like in a nearby park or even your backyard; and it will give you an opportunity to use your gear, practice some skills, and identify room for improvement before you undertake a more committing itinerary. Your goal is to replicate the elements of a real trip: hiking with a loaded pack, refilling your water bottles, changing layers, setting up your shelter, cooking a meal, etc.

A training hike in Boulder’s foothills, carrying the Osprey Aether Pro 70 pack loaded with with 50 pounds of bricks.

A training hike in Boulder’s foothills, carrying the Osprey Aether Pro 70 pack loaded with with 50 pounds of bricks.7. Final systems check

In the final days before your trip, there is a list of housekeeping items to complete, including but not limited to:

Packing up all your gear, using your gear list as a checklist, plus your maps/resources and permit;Buying any necessary perishable foods like cheese, butter, and tortilla shells;Looking at a 5-day weather forecast and adjusting your gear accordingly; and,Proof-reading your Trip Planner and leaving it with your emergency contacts.

This trip planning checklist has a more definitive list.

Questions or comments about my trip planning system?

The post Tutorial: Plan a backpacking trip in these 7 steps appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

May 8, 2020

Should I stay home or can I go? Navigating Covid-19 restrictions

Based on what we currently know about Covid-19 and on the best practices that you plan to follow, you may deem the risk of contracting or spreading Covid-19 acceptably low. And, therefore, you want to start your trip.

I would generally concur with you: thoughtful behavior in a backcountry setting — which has constant air flow and ample space, and where small groups are the norm — would not really seem demonstrably riskier than shopping at your local grocery store or running on a popular bike path.

For the 2020 season, though, I suspect that the bigger obstacle to backcountry use will not be your personal assessment of the risk but instead the layers of restrictions that have been placed on outdoor recreation and travel more broadly.

I think these restrictions are typically well-intended, even if they’re poorly nuanced or lacking factual basis. But what I think — and what you think — is irrelevant. As responsible backcountry users, it’s important to abide by the rules.

In deciding whether your trip is a go or a no-go, what conditions should you consider?

Bare shelves of toilet paper at my local supermarket. Such supply shortages (not necessarily of TP, but more critical items like beans and rice, or water purification) could amount to a “red light” for your trip.

Bare shelves of toilet paper at my local supermarket. Such supply shortages (not necessarily of TP, but more critical items like beans and rice, or water purification) could amount to a “red light” for your trip.This is a four-part series of backcountry best practices in the coronavirus era, and should be read as a whole.

Executive summaryPart 1 || Covid-19: Objective risk assessmentPart 2 || New normals: Policies and codes of conductPart 3 || Navigating restrictions on backcountry use

Green, yellow, or red?

In pondering the fate of trips I have scheduled for 2020, I’m looking at nine criteria, and assigning a red-yellow-green rating to each. A single criteria with a “red light” amounts to a deal-breaker. Ideally, they’re all green, but certain yellow lights may be acceptable.

Quarantine mandate for out-of-state visitors to Alaska, in effect through May 19, 2020

Quarantine mandate for out-of-state visitors to Alaska, in effect through May 19, 2020Stay-at-home order in your locale

Red light: Order is in effect through the starting date of the trip.Yellow light: Order is currently in effect, but set to expire before the start of the trip.Green light: No stay-at-home order in effect.

Quarantines for out-of-state visitors

Red light: Order is in effect through the starting date of the trip, unless you have the time to go through the quarantine process.Yellow light: Order is currently in effect, but set to expire before the start of the trip.Green light: Order has been lifted.

Land access

Red light: Public access to the trip location is forbidden through the start of the trip.Yellow light: Access is currently forbidden, but the ban is set to expire before the start of the trip.Green light: Public access is permitted.

Medical capacity

Red light: Medical facilities near the trip location and/or in your locale are strained by the outbreak, resulting in staff and PPE shortages, bans on elective surgeries, and overcrowded facilities.Yellow light: Medical facilities are operating near capacity or are concerned about being overwhelmed by an outbreak.Green light: Medical care is functioning normally.

Gateway communities

Red light: Binding mandates restrict access by non-locals.Yellow light: Non-binding preference for local access only.Green light: Open for business.

Trip supplies (e.g. food, fuel)

Red light: Panic or supply shortages has resulted in critical items being unavailable.Yellow light: Critical items are available if you look hard enough, or suitable substitutes can be found.Green light: Normal availability.

Rescue personnel

Red light: Official statement that personnel are not available for backcountry search and rescue.Yellow light: Exceptional discouraging of ambitious itineraries and risk-taking.Green light: Normal risk-adverse guidance.

Bailout options

Red light: Plausible scenarios where self-rescue would be impossible, combined with unavailable rescue personnel.Yellow light: Limited opportunities for self-rescue or assisted rescue.Green light: Relatively easy access if things don’t go according to plan.

Clients and guides

As a commercial operator, we must also consider the willingness and availability of our clients and guides to join and lead trips in this new coronavirus era.

Red light: Too few clients can join or too few guides can lead, in which case the trips would not be economical or the client/guide ratio would not be maintained.Yellow light: If current restrictions are not lifted soon, there is a risk of losing too many clients or guides.Green light: Enough clients and guides are available for the trips to be economical and for the minimum client/guide ratio to be maintained.

Leave a comment!

What other criteria should be accounted for in your go/no-go decision?Do you have suggestions for improving mine?

The post Should I stay home or can I go? Navigating Covid-19 restrictions appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

May 7, 2020

New normal: How can Covid-19 risk in the backcountry be minimized?

In 2020 I’m hopeful that my personal and guided backpacking trips will take place. But it won’t be business as usual — on both private and commercial outings, individual behaviors and program protocols must reflect the new risk of Covid-19.

The preceding post is an objective assessment of this risk, and it serves as a factual basis to develop and identify mitigation tactics. The prescriptions on this page are specific to my guided trip program, but they can be a starting point for other backcountry users and organizations.

This is a four-part series of backcountry best practices in the coronavirus era, and should be read as a whole.

Executive summary

Part 1 || Covid-19: Objective risk assessment

Part 2 || New normals: Policies and codes of conduct

Part 3 || Navigating restrictions on backcountry use

Big picture

The recommendations on this page are primarily designed to:

1. Prevent transmission

Covid-19 is thought to spread mainly through respiratory droplets that are produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes or talks. To prevent transmission of these droplets, take steps to:

Most importantly, create distance between people; and,

Avoid sharing potentially contaminated surfaces, especially without first washing or disinfecting them.

2. Protect vulnerable populations

The risk potential of Covid-19 is heavily skewed towards:

Older age groups, and

People with underlying health conditions.

These populations — and those close to them — must be especially conservative in their risk tolerance.

The background will look the same in 2020, but group behavior will need to change.

The background will look the same in 2020, but group behavior will need to change.Individual code of conduct

To participate in our 2020 trips, we expect the following behaviors from both clients and guides:

Pre-trip health assessment

Stay home if you:

Have symptoms consistent with Covid-19;

Had a confirmed or suspected case of Covid-19 and cannot yet discontinue home isolation per CDC guidelines; or,

Within the last fourteen days have been in contact with someone who displayed Covid-19 symptoms, at the time or since, and were not equipped with medical-grade personal protective equipment (PPE).

If you are a medical professional:

Abide by the guidelines above; and,

Contact me if you’ve been exposed to Covid-19 within the last fourteen days so that we can discuss your unique situation.

Pre-trip risk assessment

Ultimately, responsibility for your safety rests mostly with you. A group can agree to abide by best practices, but every individual must take primary responsibility for their own safety.

The risk of Covid-19 can be reduced but not eliminated, due to biological limitations and probably also to accidental human error — until everyone adjusts to these new normals, momentarily relapses to the old normal may be unavoidable. Do you accept the risk to yourself, your group, and your family and friends?

Be especially mindful if you are in a high-risk population (i.e. older and/or underlying health conditions) or cannot avoid contact with those who are.

Expect that a clause pertaining to Covid-19 will be added to our Participant Agreement, which clients have always had to sign before joining us on a trip.

Required precautions

Starting fourteen days before your trip, take steps to minimize your risk of contracting Covid-19, if you are not already doing them. This conduct should continue throughout your trip and — ideally, though it’s less consequential to those in your group — afterwards as well.

Minimize social contact.

Maintain a distance of six feet whenever possible between you and others.

Wear a face covering when you will not have a six-foot buffer for more than a few seconds.

Wash your hands with soap, especially after being in public spaces and before eating.

Abide by group size limits, which vary by jurisdiction.

Cover your face with a tissue or elbow while coughing or sneezing, and wash hands afterwards.

Respect the mitigation behaviors of others, which may be different than yours.

Equally important, do not:

Touch your mouth, nose, or eyes with unsanitary hands.

Share food or touch others’ belongings with unsanitary hands.

Share your water or water bottle.

If you are joining us in Alaska, please familiarize yourself with the Covid-19 policies for Coyote Air, our bush plane service, which are mostly consistent with our own.

Greetings

This should go without saying, but shaking hands, hugging, and high-5’s are forbidden. Instead, try one of these, or another of your choosing:

Air hugs or air high-5’s,

Slight bow,

Hand over your heart,

Blow kisses, or

A secret dance.

Travel

When we’re in the field, the risk of contracting or spreading Covid-19 intuitively seems low, due to small group sizes, constant air flow, and ample space to spread out.

For the opposite reasons, traveling to the trailhead — especially by plane or other forms of public transit — seems riskier: more interaction, less air flow, and limited social distancing options.

To help minimize your risk while traveling:

Drive if you can; fly if you must.

Socially distance, wear a mask, and wash your hands at all opportunities.

Reduce contact by starting travel with all necessary food, drink, and fuel.

Rather than staying in motels, consider camping nearby.

Only share vehicles and lodging with members of your household.

Disinfect shared surfaces before use (e.g. plane trays, rental car).

Post-trip

Have available a reliable quarantine option in the event that you feel sick or came into contact with someone who was sick.

If you develop symptoms, self-quarantine and please inform me.

Face coverings

Consider the the long-term performance of your face-covering, since you may have to wear it for extended periods while traveling and hiking. Find one that is comfortable and stays put, and that doesn’t itch or pinch.

Personally, my go-to covering has become an elasticized polyester Buff. However, while on a commercial airplane I will probably use a true mask (N95) to combat the higher risk in this setting.

Guides

Additional precautions and behaviors must be adopted by guides:

When reviewing client gear at the trailhead, do not touch it.

Favor verbal direction over physical assistance, like when setting up a client’s shelter.

Role-model good behavior. And,

Kindly enforce the new rules, and be willing to discuss the rationale openly.

It may take a few trips to get everything right — I may not have thought of everything we could do, and public guidelines will probably continue to evolve. So I’m giving guides the the discretion to improve or modify our best practices based on observation or group input. Please share feedback and tips with other guides and with me.

Client self sufficiency

Because guides will have fewer opportunities to physically assist clients, clients should practice or develop some skills beforehand, notably:

Packing your backpack;

Pitching your shelter, including knot-tying;

Operating a compass; and,

Taking care of your feet.

Diagnostics

Testing

If clients and guides were tested for Covid-19 before their trip, it would lend confidence but wouldn’t be a magic bullet:

A negative viral test offers no assurance that you did not contract the disease between the time of the test and your arrival at the trailhead; and,

A positive antibody test has not yet been proven to convey future immunity.

Rapid testing for Covid-19 at the trailhead would be more useful, but currently there are significant obstacles in making this a formal protocol.

A testing device like the Abbbot ID NOW is available only to authorized laboratories and patient care settings;

The limited testing capacity is currently being dedicated to those with symptoms; and,

For most trip locations it’d be logistically difficult to corral all clients and guides before the trip in order to be tested.

I will continue to pursue this opportunity, however, and hope that testing capacity will eventually allow for pre-screening of clients and guides.

Symptom checks

To help identify potential cases of Covid-19 within our ranks, clients and guides will complete regular symptom checks.

The first check will be done at our meetup spot, and other rounds will be done at the discretion of the guides — mornings and evenings would seem to be the most natural times.

To check for fever, no-touch thermometers will be added to the first aid kits. I may also add pulse oximeters, based on this comment, but I need to look into that.

Even if no clients or guides have Covid-19 symptoms, the core mitigating behaviors (social distancing, masks, hand-washing) must be maintained, since the group may have presymptomatic or asymptomatic carriers of the disease.

Food and meals

Preparation

The program will continue to supply breakfasts and dinners. These meals will be prepared at least 14 days in advance of your trip in accordance with normal food preparation guidelines.

Hand-washing

Before all communal meals — specifically, breakfasts and dinners — all clients and guides must wash their hands. Guides may want to make this a formal part of mealtimes.

Distribution

At the trailhead, clients and guides will be given their individual portion of the breakfasts and dinners (e.g. a bag of beans & rice, sans seasoning, cheese, and Fritos) by a guide with sanitized hands.

On 3-day trips, guides can normally carry all the group food (e.g. the cheese and Fritos), limiting opportunities for contamination. On longer trips, some share of group food usually must be carried by the clients. To help keep these food items sanitary, they will be double-bagged, and clients and guides should only access their food bags or canisters with clean hands.

In the field, guides will prepare group food items with clean hands. Spice kits can be passed around like normal, since all clients will have clean hands, too.

Instead of dividing group rations into the normal “red bowls,” each client will be given their own bowl at the trailhead that they must carry and care for. These bowls will be washed with soap and water between trips.

Post-trip meal

After each trip we normally have an optional group meal at a nearby establishment. We will look for an eatery with take-out and ample outdoor eating space.

Program policies

Group size

Normally our maximum group size is 10 (on 5- and 7-day trips) or 12 (on 3-day trips), including two guides.

Group sizes must adhere to the current restrictions imposed by local policymakers. Guidance will be sought first from the land agency; if no guidance has been given, we will look to county or state officials.

To further reduce group size, guides are permitted to split into two independent patrols, assuming that normal protocols are followed, such as having an established meetup spot and time, and have a reliable communication system between the patrols.

Route planning

For the sake of trip quality, we sought out low-use areas even before Covid-19. We will continue to find such locations in 2020, for the added purpose now of minimizing on-trail contact with others.

The chosen routes must still be appropriate for the group’s abilities and in the context of on-the-ground conditions, however. The risk of overextending a client is probably greater than the risk of sharing an outdoor space with others.

Loop itineraries will be planned so that groups do not need shuttling.

Campsite selection

Select campsites that have sufficient space to observe social distancing:

Between individual sleeping spots; and,

While eating and gathering.

This should not be a challenge for our 2020 trip locations, where generally we have lots of room to spread out. But I could see this being problematic for areas with:

Small designated campsites like Rocky Mountain National Park, or

Limited campsites and/or high-use, which will cause crowding, such as along many sections of the Appalachian Trail.

Water purification

Guides will manage the water purification process.

When Aquamira drops are being dispensed into bottles, social distancing must be maintained (by putting bottles in a central space) or masks must be worn.

To eliminate the risk that identical water bottles will be mixed up, clients and guides should mark them distinctly. Tape works best; marker/Sharpie gets rubbed off after a few days.

Close-contact sessions

It may not always be possible or desirable to maintain a six-foot distance from others, like when reading a map or spotting a client on a difficult scramble. In these close-contact sessions, all participants must wear their face covering, and the session cannot start until everyone is safely covered.

Demo gear

If clients are uncomfortable with borrowing gear from us, they should obtain their own.

Between trip locations, any virus particles on demo gear will not survive, since there’s at least a two-week gap between blocks. Thus, the first trip in every location will have reliably coronavirus-free gear.

Stove systems will be washed in hot soapy water between trips.

I’m uncertain if sleeping bags and shelters can be cleaned properly between trips, when the turnaround time is less than 24 hours, and I’m soliciting feedback. It’d be practical for the guides to use a topical spray on these items and to lay them in the sun (if available), but we don’t have the time or facilities to thoroughly wash them.

Sleeping pads will not be available until further notice. Even our pads that can be pumped remotely must be topped off with a few breaths.

First aid

Additional PPE will be added to the kits, to supplement what is used or lost during the trip.

Guides should clean their hands before using or dispensing any supplies.

Emergency protocols

Respiratory distress that cannot be resolved is a life-threatening emergency, regardless of whether it’s related to Covid-19 or not. Normal evacuation protocols should be followed while still maintaining Covid-19 best practices (social distancing if possible, mask if not, hand-washing).

In most cases of Covid-19, clients and guides would have a few days to exit the backcountry before symptoms become severe. But evacuating soon after the onset of a cough or fever would seem prudent.

Leave a comment

Do you have questions about any of these policies?

Do you feel like any are unwarranted or insufficient?

If you’re familiar with our guiding program, do you think I’ve left anything out?

The post New normal: How can Covid-19 risk in the backcountry be minimized? appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

New normal: Backcountry behaviors & protocols to reduce Covid-19 risk

In 2020 I’m hopeful that my personal and guided backpacking trips will take place. But it won’t be business as usual — on both private and commercial outings, individual behaviors and program protocols must reflect the new risk of Covid-19.

The preceding post is an objective assessment of this risk, and it serves as a factual basis to develop and identify mitigation tactics. The prescriptions on this page are specific to my guided trip program, but they can be a starting point for other backcountry users and organizations.

This is a four-part series of backcountry best practices in the coronavirus era, and should be read as a whole.

Executive summaryPart 1 || Covid-19: Objective risk assessmentPart 2 || New normal: Expected code of conductPart 3 || Navigating mandates & guidelines

Big picture

The recommendations on this page are primarily designed to:

1. Prevent transmission

Covid-19 is thought to spread mainly through respiratory droplets that are produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes or talks. To prevent transmission of these droplets, take steps to:

Create distance between people; and,Avoid sharing potentially contaminated surfaces, especially without first washing or disinfecting them.

2. Protect vulnerable populations

The risk potential of Covid-19 is heavily skewed towards:

Older age groups, andPeople with underlying health conditions.

These populations — and those close to them — must be especially conservative in their risk tolerance.

The background will look the same in 2020, but group behavior will need to change.

The background will look the same in 2020, but group behavior will need to change.Individual code of conduct

To participate in our 2020 trips, we expect the following behaviors from both clients and guides:

Pre-trip health assessment

Stay home if you:

Have symptoms consistent with Covid-19;Had a confirmed or suspected case of Covid-19 and cannot yet discontinue home isolation per CDC guidelines; or,Within the last fourteen days have been in contact with someone who displayed Covid-19 symptoms, at the time or since, and were not equipped with medical-grade personal protective equipment (PPE).

If you are a medical professional:

Abide by the guidelines above; and,Contact me if you’ve been exposed to Covid-19 within the last fourteen days so that we can discuss your unique situation.

Pre-trip risk assessment

Ultimately, responsibility for your safety rests mostly with you. A group can agree to abide by best practices, but every individual must take primary responsibility for their own safety.

The risk of Covid-19 can be reduced but not eliminated. Do you accept the risk to yourself, your group, and your family and friends?

Be especially mindful if you are in a high-risk population (i.e. older and/or underlying health conditions) or cannot avoid contact with those who are.

Expect that a clause pertaining to Covid-19 will be added to our Participant Agreement, which clients have always had to sign before joining us on a trip.

Required precautions

Starting fourteen days before your trip, take steps to minimize your risk of contracting Covid-19, if you are not already doing them. This conduct should continue throughout your trip and — ideally, though it’s less consequential to those in your group — afterwards as well.

Minimize social contact.Maintain a distance of six feet whenever possible between you and others. Wear a face covering when you will not have a six-foot buffer for more than a few seconds.Wash your hands with soap, especially after being in public spaces and before eating.Abide by group size limits, which vary by jurisdiction.Cover your face with a tissue or elbow while coughing or sneezing, and wash hands afterwards.Respect the mitigation behaviors of others, which may be different than yours.

Equally important, do not:

Touch your mouth, nose, or eyes with unsanitary hands.Share food or touch others’ belongings with unsanitary hands.Share your water or water bottle.

If you are joining us in Alaska, please familiarize yourself with the Covid-19 policies for Coyote Air, our bush plane service, which are mostly consistent with our own.

Greetings

This should go without saying, but shaking hands, hugging, and high-5’s are forbidden. Instead, try one of these, or another of your choosing:

Air hugs or air high-5’s,Slight bow,Hand over your heart,Blow kisses, orA secret dance.

Travel

When we’re in the field, the risk of contracting or spreading Covid-19 intuitively seems low, due to small group sizes, constant air flow, and ample space to spread out.

For the opposite reasons, traveling to the trailhead — especially by plane or other forms of public transit — seems riskier: more interaction, less air flow, and limited social distancing options.

To help minimize your risk while traveling:

Drive if you can; fly if you must.Socially distance, wear a mask, and wash your hands at all opportunities.Reduce contact by starting travel with all necessary food, drink, and fuel.Rather than staying in motels, consider camping nearby.Only share vehicles and lodging with members of your household.Disinfect shared surfaces before use (e.g. plane trays, rental car).

Post-trip

Have available a reliable quarantine option in the event that you feel sick or came into contact with someone who was sick.If you develop symptoms, self-quarantine and please inform me.

Face coverings

Consider the the long-term performance of your face-covering, since you may have to wear it for extended periods while traveling and hiking. Find one that is comfortable and stays put, and that doesn’t itch or pinch.

Personally, my go-to covering has become an elasticized polyester Buff. However, while on a commercial airplane I will probably use a true mask (N95) to combat the higher risk in this setting.

Guides

Additional precautions and behaviors must be adopted by guides:

When reviewing client gear at the trailhead, do not touch it.Favor verbal direction over physical assistance, like when setting up a client’s shelter.Role-model good behavior. And,Kindly enforce the new rules, and be willing to discuss the rationale openly.

It may take a few trips to get everything right — I may not have thought of everything we could do, and public guidelines will probably continue to evolve. So I’m giving guides the the discretion to improve or modify our best practices based on observation or group input. Please share feedback and tips with other guides and with me.

Client self sufficiency

Because guides will have fewer opportunities to physically assist clients, clients should practice or develop some skills beforehand, notably:

Packing your backpack; Pitching your shelter, including knot-tying; Operating a compass; and, Taking care of your feet.

Diagnostics

Testing

If clients and guides were tested for Covid-19 before their trip, it would lend confidence but wouldn’t be a magic bullet:

A negative viral test offers no assurance that you did not contract the disease between the time of the test and your arrival at the trailhead; and,A positive antibody test has not yet been proven to convey future immunity.

Rapid testing for Covid-19 at the trailhead would be more useful, but currently there are significant obstacles in making this a formal protocol.

A testing device like the Abbbot ID NOW is available only to authorized laboratories and patient care settings; The limited testing capacity is currently being dedicated to those with symptoms; and,For most trip locations it’d be logistically difficult to corral all clients and guides before the trip in order to be tested.

I will continue to pursue this opportunity, however, and hope that testing capacity will eventually allow for pre-screening of clients and guides.

Symptom checks

To help identify potential cases of Covid-19 within our ranks, clients and guides will complete regular symptom checks.

The first check will be done at our meetup spot, and other rounds will be done at the discretion of the guides — mornings and evenings would seem to be the most natural times.

To check for fever, no-touch thermometers will be added to the first aid kits.

Even if no clients or guides have Covid-19 symptoms, the core mitigating behaviors (social distancing, masks, hand-washing) must be maintained, since the group may have presymptomatic or asymptomatic carriers of the disease.

Food and meals

Preparation

The program will continue to supply breakfasts and dinners. These meals will be prepared at least 14 days in advance of your trip in accordance with normal food preparation guidelines.

Hand-washing

Before all communal meals — specifically, breakfasts and dinners — all clients and guides must wash their hands. Guides may want to make this a formal part of mealtimes.

Distribution

At the trailhead, clients and guides will be given their individual portion of the breakfasts and dinners (e.g. a bag of beans & rice, sans seasoning, cheese, and Fritos) by a guide with sanitized hands.

In the field, guides will prepare group food items (e.g. the cheese and Fritos) with clean hands. Spice kits can be passed around like normal, since all clients will have clean hands, too.

Instead of dividing group rations into the normal “red bowls,” each client will be given their own bowl at the trailhead that they must carry and care for. These bowls will be washed with soap and water between trips.

Some share of group food usually must be carried by the clients. To keep these items sanitary, clients should only access their food bags or canisters with clean hands.

Post-trip meal

After each trip we normally have an optional group meal at a nearby establishment. We will look for an eatery with take-out and ample outdoor eating space.

Program policies

Group size

Normally our maximum group size is 10 (on 5- and 7-day trips) or 12 (on 3-day trips), including two guides.

Group sizes must adhere to the current restrictions imposed by local policymakers. Guidance will be sought first from the land agency; if no guidance has been given, we will look to county or state officials.

To further reduce group size, guides are permitted to split into two independent patrols, assuming that normal protocols are followed, such as having an established meetup spot and time, and have a reliable communication system between the patrols.

Route planning

For the sake of trip quality, we sought out low-use areas even before Covid-19. We will continue to find such locations in 2020, for the added purpose now of minimizing on-trail contact with others.

The chosen routes must still be appropriate for the group’s abilities and in the context of on-the-ground conditions, however. The risk of overextending a client is probably greater than the risk of sharing an outdoor space with others.

Loop itineraries will be planned so that groups do not need shuttling.

Campsite selection

Select campsites that have sufficient space to observe social distancing:

Between individual sleeping spots; and,While eating and gathering.

This should not be a challenge for our 2020 trip locations, where generally we have lots of room to spread out. But I could see this being problematic for areas with:

Small designated campsites like Rocky Mountain National Park, orLimited campsites and/or high-use, which will cause crowding, such as along many sections of the Appalachian Trail.

Water purification

Guides will manage the water purification process.

When Aquamira drops are being dispensed into bottles, social distancing must be maintained (by putting bottles in a central space) or masks must be worn.

To eliminate the risk that identical water bottles will be mixed up, clients and guides should mark them distinctly. Tape works best; marker/Sharpie gets rubbed off after a few days.

Close-contact sessions

It may not always be possible or desirable to maintain a six-foot distance from others, like when reading a map or spotting a client on a difficult scramble. In these close-contact sessions, all participants must wear their face covering, and the session cannot start until everyone is safely covered.

Demo gear

If clients are uncomfortable with borrowing gear from us, they should obtain their own.

Between trip locations, any virus particles on demo gear will not survive, since there’s at least a two-week gap between blocks. Thus, the first trip in every location will have reliably coronavirus-free gear.

Stove systems will be washed in hot soapy water between trips.

I’m uncertain if sleeping bags and shelters can be cleaned properly between trips, when the turnaround time is less than 24 hours, and I’m soliciting feedback. It’d be practical for the guides to use a topical spray on these items and to lay them in the sun (if available), but we don’t have the time or facilities to thoroughly wash them.

Sleeping pads will not be available until further notice. Even our pads that can be pumped remotely must be topped off with a few breaths.

First aid

Additional PPE will be added to the kits, to supplement what is used or lost during the trip.

Guides should clean their hands before using or dispensing any supplies.

Emergency protocols

Respiratory distress that cannot be resolved is a life-threatening emergency, regardless of whether it’s related to Covid-19 or not. Normal evacuation protocols should be followed while still maintaining Covid-19 best practices (social distancing if possible, mask if not, hand-washing).

In most cases of Covid-19, clients and guides would have a few days to exit the backcountry before symptoms become severe. But evacuating soon after the onset of a cough or fever would seem prudent.

The post New normal: Backcountry behaviors & protocols to reduce Covid-19 risk appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

May 5, 2020

Covid-19: What’s the objective risk to backcountry travelers?

To mitigate a risk, it’s essential to first understand it. For example, if I were planning to hike the John Muir Trail/PCT in the early-season, I’d want to know about hazardous creek crossings. And if I was planning to drink water from natural sources on that trip, I would want to be familiar with the pros and cons of purification techniques.

This fact-based approach towards risk is central to both my personal and guided backpacking trips.

So before I get to specific coronavirus best practices, let’s start by discussing what we know — and, equally important, what we don’t yet know — about Covid-19, with an emphasis on the most relevant facts for an outdoor audience.

Our understanding of Covid-19 is rapidly changing. The information on this page is accurate as of the publishing date. If you feel that it has errors or omissions, please leave a comment.

This is a four-part series of backcountry best practices in the coronavirus era, and should be read as a whole.

Executive summary

Part 1 || Covid-19: Objective risk assessment

Part 2 || New normals: Policies and codes of conduct

Part 3 || Navigating restrictions on backcountry use

For most people, Covid-19 will look something like this.

For most people, Covid-19 will look something like this.The disease

Covid-19 is a novel strain of coronavirus, and is one of seven known coronavirus strains that are human transmitted. These strains are an extremely common cause of colds and other upper respiratory infections (source).

Presentation

Symptoms

A person may have Covid-19 if they have (source):

A cough, and/or

Shortness of breath;

Or at least two of the symptoms below:

Fever

Chills

Repeated shaking with chills

Muscle pain

Headache

Sore throat

New loss of taste or smell

Over the course of the disease, most persons with Covid-19 will experience the following (source):

Fever (83–99%)

Cough (59–82%)

Fatigue (44–70%)

Anorexia (40–84%)

Shortness of breath (31–40%)

Sputum production (28–33%)

Muscle aches, or myalgias (11–35%)

Headache, confusion, rhinorrhea, sore throat, hemoptysis, vomiting, and diarrhea have been reported but are less common (

Onset

Perhaps 25 percent of those who contract Covid-19 will not show any symptoms. Determining the exact prevalence of asymptomatic carriers is made difficult by the lack of widespread testing and the inaccuracy of current tests (source).

The time from exposure to symptom onset (known as the incubation period) is thought to be three to 14 days, though symptoms typically appear within four or five days after exposure (source).

People with Covid-19 may be contagious for one to three days before they show symptoms. These presymptomatic carriers are a particular challenge to containment strategies (source).

Progression of severe cases

The median time to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) ranged from 8 to 12 days, and the median time to ICU admission ranged from 10 to 12 days (source).

Severity

Hospitalization

Risk of hospitalization due to Covid-19 increases with age. Among confirmed cases in the US in March, hospitalization rates were (source):

18-49 years-old: 2.5 percent

50-64 years-old: 7.4 percent

65-74 years-old: 12.2 percent

Certain preexisting conditions also dramatically increase the risk of hospitalization. Approximately 90 percent of hospitalized Covid-19 patients had an underlying condition, notably:

Hypertension (50 percent)

Obesity (48 percent)

Chronic metabolic disease, e.g. diabetes (36 percent)

Chronic lung disease (35 percent)

Heart disease (28 percent)

Mortality

Among confirmed Covid-19 cases, the mortality rate currently ranges from 0.1 percent in Qatar to 15.8 percent in Belgium. In the US, it’s 5.8 percent. This huge variability is a function of testing, country demographics, the quality of care, and data accuracy (source).

As researchers better understand the prevalence of Covid-19, the mortality rate will likely change. A study by Stanford researchers self-published in mid–April found that there may be 50 to 85 times more infected people in Santa Clara, Calif., than confirmed cases, which would lower the mortality rate proportionally. However, the methodology has been strongly criticized.

Evidence also exists to support the opposite argument. The comparison of all deaths in spring 2020 versus historical normals suggests that Covid-19 deaths have been under-reported.

Like the hospitalization rate, the mortality rate increases with age. I’ve struggled to find recent national data; as of late-April in New York City, death rates were:

20-29 years-old: 0.2 percent

30-39 years-old: 0.2 percent

40-49 years-old: 0.4 percent

50-59 years-old: 1.3 percent

60-69 years-old: 3.6 percent

70-79 years-old: 8.0 percent

80+ years-old: 14.8 percent

I’ve also struggled to find mortality data that looks specifically at underlying conditions. But it seems reasonable that the relationship between underlying conditions and hospitalizations (90 percent) also holds true for the relationship between underlying conditions and mortality.

Relative to other respiratory diseases, Covid-19 is less fatal than severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) or Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), which had mortality rates of 10 and 34 percent, but more fatal than the seasonal flu (0.1 percent) (source). For specific mortality rates of the influenza, refer to CDC data.

Transmission

The infectious dose is the amount of virus needed to establish an infection. Scientists do not yet know how many virus particles of Covid-19 are needed to trigger infection. Based on the global spread of the virus, it’s clearly very contagious. Two potential explanations (source):

Few particles are needed for infection;

Infected people release a lot of virus in their environment.

Early data from multiple contact tracing studies suggest that close and prolonged contact is required for transmission, and that the risk is highest in enclosed environments with multiple people (houses, long-term care facilities, shelters, public transport, offices). Casual and short interactions are not the main cause of the epidemic.

In short, you want to avoid the three C’s: Conversations in poorly ventilated Closed, Crowded spaces.

Airborne

The virus that causes Covid-19 is thought to spread mainly through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or spits while talking. These droplets can:

Land in the mouth, nose, or eye of a person nearby,

Be inhaled into the lungs, or

Introduced into the body by touching the nose, mouth, or eyes with an infected surface, like your fingers.

Spread is more likely when people are in close contact with one another, within about 6 feet (source).

Covid-19 particles have been found in finer aerosols, such as from exhaled breath (source), but it’s uncertain if these particles are sufficient to cause infection (source). In an outdoor setting, these aerosols are probably less of a concern than in confined spaces with many people and poor airflow.

Surfaces

Particles of Covid-19 have been shown to stay viable on surfaces like printing paper (3 hours) and plastic (3 to 7 days). But, like aerosols, it’s unclear if the amounts are sufficient to cause infection, and infection is entirely dependent on having a path into the respiratory system (source).

Water and food

Per the FDA, “Foodborne exposure to [Covid-19] is not known to be a route of transmission.” The CDC agrees.

I have not found information on the transmissibility of Covid-19 in water. For good measure, treat natural sources with chlorine dioxide or a UV light, two recommended water purification techniques that are effective against viruses.

When outdoors

Scant research has been done on the transmission of Covid-19 in an outdoor setting. A study of 318 outbreaks with 1245 confirmed cases in China traced only two cases (0.16 percent) to outdoor transmission. However, the study did not account for the proportion of time spent outdoors by the study group.

Intuitively, it would seem more difficult to absorb an infectious dose while outside, because Covid-19 particles are dispersed by airflow and probably also killed fairly quickly by sunlight (source). This article discusses infectious dose in the context of hiking, running, and cycling outdoors.

Testing

Two kinds of tests are available for COVID-19:

A viral test tells you if you have a current infection.

An antibody test tells you if you had a previous infection

An antibody test may not be able to show if you have a current infection, because it can take 1-3 weeks after infection to make antibodies. We do not know yet if having antibodies to the virus can protect someone from getting infected with the virus again, or how long that protection might last (source).

It’d be enormously helpful if testing for Covid-19 was more widespread and accurate. But it hasn’t been; it’s not yet; and it probably won’t be in time for the 2020 backpacking season. Read this op-ed for a good synopsis of the situation.

Treatment

There is no cure for Covid-19. One drug, remdesivir, has been shown to modestly reduce recovery time (source), and was granted emergency FDA authorization on May 1, 2020.

Antibiotics aren’t effective against viral infections such as Covid-19 (source).

The CDC recommends resting and hydrating to help manage symptoms at home.

Precautions

To reduce the risk of contracting or spreading Covid-19, health experts recommend three measures:

1. Social distancing

The most effective method to reduce Covid-19 risk is avoiding close contact (within 6 feet) with others for a prolonged period of time to prevent the transmission of respiratory droplets.

The exact length of time that constitutes a “prolonged period” is not certain. Recommendations range from just a few minutes in a healthcare setting, to 10 to 30 minutes outside of one (source).

2. Wear a face covering

When social distancing cannot be practiced, wearing a non-medical mask can protect you from others, and others from you. Masks should be washed periodically.

The efficacy of homemade masks is questionable due to cloth porosity and imperfect seals (source). It might be considered a “better than nothing” preventative measure.

3. Wash your hands

To remove viruses you have picked up from others or from surfaces, wash your hands for at least 20 seconds with soap and warm water. Even standard soap is more effective than alcohol-based hand sanitizer, though sanitizer will also work and it’s sometimes more convenient.

Leave a comment!

Is this page in error, or not clear?

What important facts about Covid-19 have been omitted?

The post Covid-19: What’s the objective risk to backcountry travelers? appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

Covid-19: Objective risk assessment for backcountry travelers

To mitigate a risk, it’s essential to first understand it. For example, if I were planning to hike the John Muir Trail/PCT in the early-season, I’d want to know about hazardous creek crossings. And if I was planning to drink water from natural sources on that trip, I would want to be familiar with the pros and cons of purification techniques.

This fact-based approach towards risk is central to both my personal and guided backpacking trips.

So before I get to specific coronavirus best practices, let’s start by discussing what we know — and, equally important, what we don’t yet know — about Covid-19, with an emphasis on the most relevant facts for an outdoor audience.

Our understanding of Covid-19 is rapidly changing. The information on this page is accurate as of the publishing date. If you feel that it has errors or omissions, please leave a comment.

This is a four-part series of backcountry best practices in the coronavirus era, and should be read as a whole.

Executive summaryPart 1 || Covid-19: Objective risk assessmentPart 2 || New normal: Expected code of conductPart 3 || Navigating mandates & guidelines

For most people, Covid-19 will look something like this.

For most people, Covid-19 will look something like this.The disease

Covid-19 is a novel strain of coronavirus, and is one of seven known coronavirus strains that are human transmitted. These strains are an extremely common cause of colds and other upper respiratory infections (source).

Presentation

Symptoms

A person may have Covid-19 if they have (source):

A cough, and/or Shortness of breath;

Or at least two of the symptoms below:

FeverChillsRepeated shaking with chillsMuscle painHeadacheSore throatNew loss of taste or smell

Over the course of the disease, most persons with Covid-19 will experience the following (source):

Fever (83–99%)Cough (59–82%)Fatigue (44–70%)Anorexia (40–84%)Shortness of breath (31–40%)Sputum production (28–33%)Muscle aches, or myalgias (11–35%)

Headache, confusion, rhinorrhea, sore throat, hemoptysis, vomiting, and diarrhea have been reported but are less common (

Onset

Perhaps 25 percent of those who contract Covid-19 will not show any symptoms. Determining the exact prevalence of asymptomatic carriers is made difficult by the lack of widespread testing and the inaccuracy of current tests (source).

The time from exposure to symptom onset (known as the incubation period) is thought to be three to 14 days, though symptoms typically appear within four or five days after exposure (source).

People with Covid-19 may be contagious for one to three days before they show symptoms. These presymptomatic carriers are a particular challenge to containment strategies (source).

Progression of severe cases

The median time to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) ranged from 8 to 12 days, and the median time to ICU admission ranged from 10 to 12 days (source).

Severity

Hospitalization

Risk of hospitalization due to Covid-19 increases with age. Among confirmed cases in the US in March, hospitalization rates were (source):

18-49 years-old: 2.5 percent50-64 years-old: 7.4 percent65-74 years-old: 12.2 percent

Certain preexisting conditions also dramatically increase the risk of hospitalization. Approximately 90 percent of hospitalized Covid-19 patients had an underlying condition, notably:

Hypertension (50 percent)Obesity (48 percent)Chronic metabolic disease, e.g. diabetes (36 percent)Chronic lung disease (35 percent)Heart disease (28 percent)

Mortality

Among confirmed Covid-19 cases, the mortality rate currently ranges from 0.1 percent in Qatar to 15.8 percent in Belgium. In the US, it’s 5.8 percent. This huge variability is a function of testing, country demographics, the quality of care, and data accuracy (source).

As researchers better understand the prevalence of Covid-19, the mortality rate will likely change. A study by Stanford researchers published in mid–April found that there may be 50 to 85 times more infected people in Santa Clara, Calif., than confirmed cases, which would lower the mortality rate proportionally. However, the methodology has been strongly questioned.

Evidence also exists to support the opposite argument. The comparison of all deaths in spring 2020 versus historical normals suggests that Covid-19 deaths have been under-reported.

Like the hospitalization rate, the mortality rate increases with age. I’ve struggled to find recent national data; as of late-April in New York City, death rates were:

20-29 years-old: 0.2 percent30-39 years-old: 0.2 percent40-49 years-old: 0.4 percent50-59 years-old: 1.3 percent60-69 years-old: 3.6 percent70-79 years-old: 8.0 percent80+ years-old: 14.8 percent

I’ve also struggled to find mortality data that looks specifically at underlying conditions. But it seems reasonable that the relationship between underlying conditions and hospitalizations (90 percent) also holds true for the relationship between underlying conditions and mortality.

Relative to other respiratory diseases, Covid-19 is less fatal than severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) or Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), which had mortality rates of 10 and 34 percent, but more fatal than the seasonal flu (0.1 percent) (source).

Transmission

The infectious dose is the amount of virus needed to establish an infection. Scientists do not yet know how many virus particles of Covid-19 are needed to trigger infection. Based on the global spread of the virus, it’s clearly very contagious. Two potential explanations (source):

Few particles are needed for infection;Infected people release a lot of virus in their environment.

Airborne

The virus that causes Covid-19 is thought to spread mainly through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or spits while talking. These droplets can:

Land in the mouth, nose, or eye of a person nearby,Be inhaled into the lungs, orIntroduced into the body by touching the nose, mouth, or eyes with an infected surface, like your fingers.

Spread is more likely when people are in close contact with one another, within about 6 feet (source).

There is some evidence to suggest that Covid-19 particles can be transmitted through finer aerosols from exhaled breath, though it’s unclear if this could constitute an infectious dose.

Surfaces

Particles of Covid-19 have been shown to stay viable on surfaces like printing paper (3 hours) and plastic (3 to 7 days). But, like aerosols, it’s unclear if the amounts are sufficient to cause infection, and infection is entirely dependent on having a path into the respiratory system (source).

Water and food

Per the FDA, “Foodborne exposure to [Covid-19] is not known to be a route of transmission.” The CDC agrees.

I have not found information on the transmissibility of Covid-19 in water. For good measure, treat natural sources with chlorine dioxide or a UV light, two recommended water purification techniques that are effective against viruses.

When outdoors

Scant research has been done on the transmission of Covid-19 in an outdoor setting. A study of 318 outbreaks with 1245 confirmed cases in China traced only two cases (0.0016 percent) to outdoor transmission. However, the study did not account for the proportion of time spent outdoors by the study group.

Intuitively, it would seem more difficult to absorb an infectious dose while outside, because Covid-19 particles are dispersed by airflow and also killed by sunlight. This article discusses infectious dose in the context of hiking, running, and cycling outdoors.

Testing

Two kinds of tests are available for COVID-19:

A viral test tells you if you have a current infection.An antibody test tells you if you had a previous infection

An antibody test may not be able to show if you have a current infection, because it can take 1-3 weeks after infection to make antibodies. We do not know yet if having antibodies to the virus can protect someone from getting infected with the virus again, or how long that protection might last (source).

It’d be enormously helpful if testing for Covid-19 was more widespread and accurate. But it hasn’t been; it’s not yet; and it probably won’t be in time for the 2020 backpacking season. Read this op-ed for a good synopsis of the situation.

Treatment

There is no cure for Covid-19. One drug, remdesivir, has been shown to modestly reduce recovery time (source), and was granted emergency FDA authorization on May 1, 2020.

Antibiotics aren’t effective against viral infections such as Covid-19 (source).

The CDC recommends resting and hydrating to help manage symptoms at home.

Leave a comment!

Is this page in error, or not clear?What important facts about Covid-19 have been omitted?

The post Covid-19: Objective risk assessment for backcountry travelers appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

Backcountry best practices in the coronavirus era

The novel coronavirus has upended life as we once knew it. With therapeutic treatments and vaccines, we’ll revert to our old normal eventually, but in the meantime we’ll have to learn to live with it — How can we still work and play without compromising our own safety or that of our family, friends and neighbors?

As an avid backpacker and the owner of a backpacking guide service, I’m particularly motivated to develop and adopt backcountry best practices for this coronavirus era. A fact-based set of policies and protocols can help to reduce risk, minimize unfounded fears, and perhaps even encourage land managers to lift restrictions.

This four-part series is specifically designed for my guided trip program, but it has significant relevance to the broader backpacking and outdoor communities. Some of it was directly influenced by reader feedback to a very popular post from last month, “When & how will backpacking be safe and feasible again?”

Guidelines and table of contents

What have I accounted for in these best practices? For more bite-sized reading, I have given each main consideration a dedicated page, and will update links as I publish them:

What are the symptoms of Covid-19? How is it transmitted? Who is most at-risk? And, importantly, what do we not yet know about it?

Part 2: The activity

A one-size-fits-all set of best practices won’t get it right for everyone. Instead, adjust the specifics for your unique situation, such as risk profile, group size, and location.

Part 3: The restrictions

How should we navigate the layers of restrictions that have been placed on outdoor recreation and broader travel?

Social distancing at 12,000 feet on Snow Mesa in southwestern Colorado

Social distancing at 12,000 feet on Snow Mesa in southwestern ColoradoExecutive summary

Backcountry travel — and life, more generally — has never been risk-free. In an ordinary season, I will encounter swift water, lightning, grizzly bears, steep snowfields, cold soaking rain, and shifting talus, among other variables that are inherently not safe, oftentimes while leading a group of clients.

That may sound like chest-beating, but I point this out because I’m approaching Covid-19 the same way that I address every other risk:

Understand it, and

Take steps to mitigate it.

With mitigation efforts that focus on distancing and surfaces, the risk of COVID-19 can be greatly reduced. It will not be zero, however. So there is a matter of individual choice. Are you willing to accept some level of risk so that you can hike, camp, run, climb, and ride? Or will you wait this out at home?

For me — and probably many others — that choice is easy. So the more consequential issue may be the the multitude of mandates, advisories, and decisions made by government representatives, health officials, land agencies, communities, business owners, and search-and-rescue teams. Even if you decide that the risk of Covid-19 is acceptably low, your trip may be ill-advised, impractical, or illegal because of these overarching conditions.

Why am I sharing this here?

I have not before shared core program resources, like our emergency protocols or operations plan. But posting these best practices online has multiple advantages:

1. Clients and land agencies rightfully want to know how we are handling this risk. I can easily point them here, where I can keep our policies current as we learn more about the virus.

2. Organizations large and small are trying to figure this out, and I certainly don’t have all the answers. In this case, more heads is better than one, and I’m hoping that public feedback can lead to marginal improvements.

3. Covid-19 has been a monkey wrench for many organizations, including mine. Perhaps I can help save time and improve program safety for a hiking club, Scout troop, or less established guide service.

Disclaimers

1. The extent of my medical training an 80-hour wilderness first responder course plus biannual 24-hour re-certifications. So don’t put stock in my medical advice, though I think you’ll find the content to be consistent with the opinions of medical experts.

2. Our understanding of COVID-19 is rapidly changing, and I expect to update my policies and recommendations accordingly. These pages should be accurate as of the most recent publishing date.

The post Backcountry best practices in the coronavirus era appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

Face Your Fears: The real risk of wild animals & injuries for women

As a female outdoor leader, guide, and mentor, I hear a wide range of worries that women have about being outdoors. Wild animals and injuries are two of the most common.

I’m here to tell you that women are no more vulnerable than anyone else outdoors.

Real vs. Perceived Risks

The first night I camped solo, I too was terrified, to the degree that I even zip-tied the inside zippers of my tent together so that nothing could come in. I was convinced that every noise outside was a wild animal, and I felt tiny, alone, and vulnerable.

I barely slept that night, and woke up the next morning feeling exhausted and embarrassed — there was nothing to be afraid of. It has taken years for this feeling to disappear, and I still sleep with earplugs, but it will dissipate.

It’s worth noting that many women — myself included — were brought up in an environment of fear. We were conditioned to believe that we are not as strong, brave, or capable as men; and we often carry these thoughts with us into our adult lives.

These messages are often unfortunately reinforced by the hiking community. When embarking on an outdoor adventure, I have observed that women are more often told, “Be safe,” rather than a more encouraging, “Have fun.” It’s my experience that our abilities are questioned more often, and that our bravery and independence are at a higher risk of being rebranded as stupidity. It’s no wonder that we internalize these messages.

The statistics tell another story. The outdoor risk profile starts from the same baseline for men and women, but may not stay there. A recent example can be seen in the search and rescue responses in the National Parks in 2017 showing men as significantly more frequent rescue subjects, despite the Outdoor Industry Association reporting an almost even gender parity in outdoor recreation participation since 2016. (Apologies to non-binary folks who are not yet included in these data sets.)

Now let’s talk about those top two fears.

Wild Animals

We share our wild spaces with the animals that call them home, and it’s very possible to encounter bears, cougars, mountain goats, and other larger mammals in the wilderness.

It’s worth noting, however, that the odds of a fatal wildlife encounter are extremely low. It’s not statistically impossible and it doesn’t invalidate the very real feelings about the possibility, but the numbers help put things in perspective.

According to Yellowstone National Park, the probability of being killed by a bear in the park (8 incidents) is only slightly higher than the probability of being killed by a falling tree (7 incidents), in an avalanche (6 incidents) or being struck and killed by lightning (5 incidents). Oh. And that urban legend about bears being attracted to menstruating women? That’s almost entirely garbage unless you’re dealing with polar bears.

The best offense is often a good defense. The vast majority of wild animals will avoid humans when possible.

Here are some solid strategies to minimize large mammal wildlife encounters:

Hike in groups.

Make noise.

Avoid hiking at dawn and dusk.

Avoid areas with recently documented wildlife encounters. And,

Never approach wild animals.

It is also important to practice Leave No Trace practices while backcountry camping. The following best practices are recommended to avoid unexpected wildlife visitors:

Never eat in or near your tent.

Keep all food and scented items a minimum of 300 ft. away from your campsite. And,

Check every pocket for scented items before bedtime.

Have you done everything you can to avoid encounters and suddenly find a black bear on the trail? Do not panic. Take a deep breath and assess the situation before responding. Use the following tips to defuse encounters.

Black Bears

Don’t run.

Talk softly.

Back away slowly while facing the bear.

Cougars & Mountain Goats

Don’t run.

Talk firmly and aggressively — convey that you are not prey.

Back away slowly while facing the animal.

Appear big — raise your arms and/or trekking poles above your head.

Injuries

Unfortunately, injuries happen in the great outdoors. The realities of bad weather, uneven/unstable terrain, medical issues, and generic bad luck are sometimes unavoidable factors in outdoor adventures.

The best approach is to do everything you can to anticipate, avoid, and be prepared for these scenarios should they occur.

This starts with a solid wilderness trip plan, essential gear, and as much advance knowledge as possible about your adventures. This includes the following key preparedness items before hitting the trail.

Trail map & route plan

Navigation tools & know-how

Weather forecast information

Recent trail conditions reports

Weather appropriate gear & clothing

Detailed trip plan left with trusted contacts

It’s also important to have tools to respond to situations if they occur. This includes the following essential preparation areas:

First aid kit (ex. blisters, burns, cuts, etc.)

Ten essentials

Extra insulation layers for unexpectedly long days

Recommended: wilderness first aid training

Optional: personal location beacon

Mindset

We as women are no more vulnerable in the outdoors than anyone else.

I encourage you to prepare well, anticipate what you can, and step out on the trail with confidence. Things can happen to anyone out there, always listen to your gut, but don’t let fear hold you back.

Embrace this glorious unknown and your ability to handle issues as they arise as a part of the overall adventure. You are strong, confident, and prepared. See you on the trail.

The post Face Your Fears: The real risk of wild animals & injuries for women appeared first on Andrew Skurka.

April 30, 2020

Virtual clinic: How to plan a backpacking trip

Next month I’m hosting a free virtual clinic in partnership with the Colorado Mountain Club. Originally we’d scheduled an in-person gear and skills clinic in Golden, which I do most years for them, but, well, you know what happened.

Key event details:

Topic: Seven steps to plan a backpacking tripOnline tutorial via ZoomThursday, May 7 at 7pm MDTFREE with suggested donations to Colorado Mountain Club RSVP to reserve your spot

Event description

Join Colorado Mountain Club for a virtual clinic with Andrew Skurka, who has been recognized by both National Geographic and Outside as an “Adventurer of the Year” for his long-distance hikes.

Andrew Skurka is a master trip planner. This year alone he is organizing 29 trips for nearly 250 guided clients, and previously he has planned multi-month solo trips like his 6,875-mile Great Western Loop and 4,700-mile Alaska-Yukon Expedition.

To pull this off, he uses a comprehensive trip planning framework that is applicable to all locations, seasons, experience levels, group sizes, and backpacking styles. In this 90-minute online seminar, Skurka will share this process and highlight helpful tools and resources.

The 2020 season is likely to be short — learn to plan trips efficiently so that you can maximize every day of it!

A long time friend of the CMC, Andrew has made this clinic available to CMC members and our community for free, with suggested donations to the CMC during the tough times we have faced during the COVID-19 pandemic with regard to canceled classes, events, and programs.

The clinic will be held on Zoom and will begin at 7pm MST and run 90 minutes with a Q&A for participants.

This event is part of the CMC’s new online learning content on the Colorado Mountain Club Online University page. Check out the full page of content and be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel.

RSVP now to join this clinic.

The post Virtual clinic: How to plan a backpacking trip appeared first on Andrew Skurka.