Rosalind Wiseman's Blog, page 24

May 4, 2017

“Where Everyone Belongs”: Conversation with Students in Environmental Leadership Class Going Beyond the Classroom

Young people getting along? Young people being themselves? Young deeply people caring about the environment and their place in the world? Kinard CARES has figured it out.

We visited with a group of awesome students selected to be a part of an 8th grade environmental leadership class called Kinard CARES at Kinard Middle School in Fort Collins, CO. Kinard CARES is a year-long elective class based on raising environmental awareness while making a difference in our local community. The peak experience of the class is a trip to Catalina Island, CA where students participate in a week-long environmental leadership and service learning camp understanding their role as global citizens.

Cultures of Dignity sat down with Assistant Principal and leader of Kinard CARES, Chris Bergmann, and six passionate 8th grade students (Jordan, Zoie, Nathan, MacKenzie, Payton, and Kylie) to talk about what this experience means to them. We were shocked at how articulate and passionate they were in their responses! Check out the conversation on how these students have grown as leaders in their community and lessons from spending a week on an island.

Cultures of Dignity: Alright you all, this class seems too good to be true! A trip, environmental leadership, and you all like each other?! Tell me a little bit about Kinard CARES and why you wanted to join?

Mr. Bergmann: Kinard CARES started with student passion and interest and was completely student-driven from the beginning. The best learning happens when we provide students with authentic engaging and real-world experience that reflects their civic duties. If they feel like the work they are doing is going to leave a legacy, then you have won. If we can get kids to develop an empathy and emotional response to the natural world and if they fall in love with it at a young age then they will be empowered to serve and protect it.

Kylie: The groups before us came into our class in 6th grade and I identified them as the leaders of the school, they were all one big family, and I wanted to be apart of that.

Payton: I saw that it changed the groups ahead of us, it gave them a new perspective on the world and I wanted that for myself.

MacKenzie: Previous generations had this special dynamic that you don’t come across often. I saw what they did for the school, for the world, and others and it really intrigued me.

2016-2017 Kinard CARES group on Catalina Island

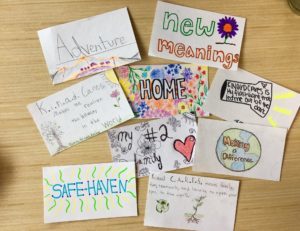

Cultures of Dignity: So you’ve been in class for a year now, in one phase, what does being a part of this group mean to you?

Jordan: Crazy, amazing experiences

Zoie: New meanings

Nathan: When a group of people get together with a common goal, they can achieve it no matter how hard it is

Mackenzie: Where everyone belongs

Payton: My second family, where you learn something new every day

Kylie: A safe haven – where we can all share our ideas without being judged

Other submissions by Kinard CARES students

Cultures of Dignity: Our work is all about culture and dignity and how those play out in the dynamic of any group. What’s it like being together and what have you learned?

Kylie: The group dynamic of this class is amazing, you know everyone on a deeper level and you can share things that you wouldn’t share with other people. When they smile you want to smile, they are the only ones who really know you.

Mackenzie: I learned to be your true self, to not care what other people think and to not be judgmental.

Zoie: It is harder to be someone else than to be yourself.

Nathan: You don’t have to try and fit in or be something that you are not.

Cultures of Dignity: Mr. Bergmann told us that when you’re in Catalina you’re doing a lot of leadership activities, team building, and service learning, but can you tell us about what the trip meant to you?

Nathan: On Catalina you aren’t controlled by friends or what others want you to be. Don’t have to worry about parents, your school work, soccer, and other activities, you can just be yourself on the island.

Payton: In 7th grade, I knew everyone on a shell level and have an idea of what their personality is but when you go on the trip you figure out who they really are instead of who you thought they were.

Mr. Bergmann: I keep taking students on this trip because it is the last time that you might feel completely free to play and just be. The island allows you to take safe risks and have natural consequences. At home you feel like you can’t get dirty and out there it’s a safe way to learn. It’s the last time in your life where you fully feel free to play, without sports, grades, pressure, to just be.

Nathan: One time I was all alone and I climbed to the top of this giant rock and just sat. I gained a better appreciation for being quiet and being alone. There is always noise here and on the island it was a way to escape the noise.

Mr. Bergmann: Yes, and sometimes the voice that gets drowned out by the noise is your own voice.

Kylie: I remember one time a group of us just sat in silence on the beach for a really long time and then started talking about all the stresses that we did leave back at home and we were sad about it and then we learned that we could just use this as a stepping stone for going in a new direction when we get back.

Cultures of Dignity: This sounds like an incredible experience! What else have you gotten out of it? I imagine a lot.

Jordan: It’s given me a new appreciation for leadership, sometimes I feel like in order to be a good leader you have to know when the right time to lead and when the right time to step back and let other people lead. A good leader puts the people they are leading above their needs

Nathan: What you put into it you get out of it. We put in so much and got a lot out of it too.

Peyton: You can’t be afraid to make a difference and to take on the work and make the change happen.

Mackenzie: These skills won’t just stop in 8th grade. The skills we learn will carry on the rest of our lives. We can pull experience from this class to help us later on in life.

Recent Posts

“Where Everyone Belongs”: Conversation with Students in Environmental Leadership Class Going Beyond the Classroom

What Should You Say When Your Child Tells You They’ve Been a Bystander to Bullying?

White Boy Problems

7k

7k

10k

10k

Follow

Follow

April 20, 2017

What Should You Say When Your Child Tells You They’ve Been a Bystander to Bullying?

What Should You Say When Your Child Tells You They’ve Been a Bystander to Bullying?

By Rosalind Wiseman

Did that person really just do that? What should I do? Maybe it wasn’t that bad … I should just pretend it didn’t happen.

All of us have been a bystander to bullying at some point in our lives.

These situations are so hard, no matter how old we are. Yet we often don’t admit how difficult it truly is to act — as if it’s easy to speak out against bullying, and do so effectively. But it’s a very complicated process: Our brains make a series of complex decisions that we usually don’t have time to articulate, even to ourselves and, before we know it, we’ve reacted to the situation. We’ve pretended to ignore what happened, laughed it off, or backed up the person being mean. Or we’ve stayed neutral and “stayed out of it” — which certainly doesn’t look neutral to the target.

When you’re a child or a teen, it’s even harder to act because it can feel like the bully has enormous, almost mythological power over you. It feels like if you speak up, your life will be over because every friend will abandon you. The children and teens I work with have told me how complicated the decision of whether to speak out or not can be. Choosing when they intervene typically depends on how well they know the person. If it’s at school and they see it going on with a group of people who aren’t their friends, they think it would be weird to intervene. After all, they could be misinterpreting what happened and, if it was really that bad, wouldn’t one of the kids who knows the situation better do something about it?

When you’re a child or a teen, it’s even harder to act because it can feel like the bully has enormous, almost mythological power over you. It feels like if you speak up, your life will be over because every friend will abandon you.

Adults can’t gloss over how hard this is when we try to encourage kids to speak out against bullying, or ask them a million questions about what they did in the moment and tell them what they should have done instead. Remember: If you weren’t there, you don’t know how hard it was.

There are two different kinds of bystanding: when you see it in the moment, and when you are witness to a pattern of behavior that you don’t agree with. The first demands split-second decision making. The second gives you some time to prepare what you want to say, to whom, and where you’ll say it.

At some point every kid will be a bystander. So before they’re even in that situation, it’s important for them to stop and think about what’s the theoretical minimum they’d want to do. Pull the victim away? Distract the bully? Tell them to stop? If so, what’s the most general, realistic thing they can visualize saying?

The reality is that usually bystanders don’t figure out what they should have said until after the moment passes. Here’s what I tell young people to keep in mind about bystanding:

It’s never too late.

If you don’t handle the situation in a way you feel proud of, you can always go back and address it later. Here’s what you can say to the bully: “Yesterday when you said X to that person, it was wrong. I didn’t say anything when it happened because I was surprised and unprepared, but I want to tell you now.”

It’s always hard and uncomfortable.

No one wakes up in the morning looking forward to telling someone they’re wrong. That doesn’t mean it’s okay to stay silent, but it does mean it’s critical to acknowledge that it takes a lot of courage to tell anyone you don’t like something they did.

People don’t always laugh when they think something is funny.

Sometimes people laugh when they’re nervous or uncomfortable. But you can always go back and tell the bully later, “I laughed yesterday when you did X, but I laughed because the whole thing made me nervous. I didn’t think it was funny. That kid really didn’t like it.”

You can talk to the target.

You can always apologize to the target for not handling it the way you would have wanted. At the very least, talking to the target about it tells them they aren’t alone. And maybe you can brainstorm together how you want to handle it if it happens again.

Getting involved doesn’t depend on how much you like the person.

Speaking out when someone is being bullied shouldn’t be based on how you feel about the target or the bully. Getting involved should be based on whether someone’s dignity isn’t being respected. If that’s happening, bystanders need to speak out.

Sometimes it can be too dangerous to intervene all by yourself.

If you are in a situation where your physical safety is at risk, you should go get an adult to help. Before you run off to find a grown-up, stop for one moment to think about where the closest adult is. You want to run towards help and safety as quickly as you can — and that one moment of thinking where to go can make a huge difference.

No matter what, somewhere along the line we will all be bystanders so we all need to have some empathy for each other. We can only encourage others to speak out when we collectively support one another.

This post originally appeared on Brightly.

Recent Posts

What Should You Say When Your Child Tells You They’ve Been a Bystander to Bullying?

White Boy Problems

Risk Factor: The Truth about Dares

7k

7k

10k

10k

Follow

Follow

April 10, 2017

White Boy Problems

By: Rosalind Wiseman

I’ve been working with teens and parents for over twenty years and lately I’ve been getting a lot of questions about how to talk about racism and privilege without people getting defensive and jumping to the worst of conclusions about each other. Here’s one question from a mother I recently received:

My 16-year-old son is an open-minded person who sees people for what they do, not what they look like. I’m proud of his acceptance of people who are different than him. He’s politically savvy and we’ve had many discussions about the election. Out of the blue the other day he said that he feels hated because he is a white male. He doesn’t want to be defensive but it’s hard to know what to tell him when so many seem to be against the demographic that he fits into. I’m sure he’s not alone in feeling this way. Any thoughts?

Here’s the truth: None of us are entirely open-minded. It’s like when people say, “I don’t see color” or “I don’t have a racist bone in my body.” Not possible. People only say that if they don’t know how racism and bigotry work. We have all been raised to judge people based on race, class, and how we conform to cultural rules about how we “should” look or act. The sooner we admit it, the sooner we can have more interesting, honest conversations. We are creating a reinforcing cycle; the more we cling to the belief that we are free of bias, the more defensive, blind, and deaf we are to our biases.

We are creating a reinforcing cycle; the more we cling to the belief that we are free of bias, the more defensive, blind, and deaf we are to our biases.

What does this mean for your son? As the mother of two white boys myself, this is something I think about as well. Your son, like my boys, has the right to his experiences and his feelings about those experiences — just like everyone else has the right to theirs. And I’m sure it’s annoying for him to experience people making negative assumptions about him because he is a white male. But it’s also time for him to grow up. For example, black women put up with people’s negative assumptions about them on a regular basis.

It’s exhausting choosing which battles to fight and how to fight them — without being stereotyped as an “angry black woman.” It’s part of their lived experience. So it’s good for your son to be uncomfortable. It’s good for him to feel what it’s like for people to make assumptions about him that he thinks are unfair and inaccurate. It’s good for him to feel what it’s like to be labeled. Then he can take those experiences, learn from them, and use them to increase his own understanding of the people who live around him.

But how? Even well-intentioned people in his situation can be nervous about making “a mistake” and saying the wrong thing. But there’s also a lot of willful ignorance and callousness out there. I’ve had several teen boys say recently that they just wished people would stop talking about race and that if we did, it would stop racism from happening. It’s an illogical argument — the people who experience racism and discrimination have no choice but to think about it and talk about it because it’s part of their everyday experience. It’s only people who are not discriminated against that believe this argument makes sense because they can convince themselves that the problem doesn’t exist. But their response is motivated by fear — fear of not knowing how to be with people who have a different life experience, fear of facing a person’s anger, and fear that people who have been systematically disempowered will be given equal power and voice.

If your son really wants to address this issue here are some responses he can use when the conversation makes him defensive or he wants to rage:

I’m asking because I’m curious and I really want to know what you think and how you experienced x.

If I say something that comes across as hurtful or ignorant, I want you to tell me.

Help me understand…

I’m asking that you listen to me and don’t assume I’m only what you see. Yes, I’m male and white but I’m also a lot of other things. It doesn’t take away from my privilege but the other parts of me are important to who I am and how I want to show up in the world.

He also need to challenge himself. Is he willing to speak out when he sees other people, especially people who look like him, abuse their privilege? The reality is that many young, white men don’t speak out when their white, male peers abuse their privilege. They stand by and laugh. They stand by and make excuses. They stand by and tell the person who is being dismissed to let it go and stop making such a big deal of it. If your son really wants people to see beyond his gender and race, that he needs to act out and speak against white male privilege when he sees it in his own life.

Because the bottom line is real men, honorable men, are strong enough to be uncomfortable with their privilege, have the courage to stay in conversations with people who may be angry at what our sons represent, and have the confidence to speak out against bigotry in any form. It’s the only way he’s going to break out of the box he says he doesn’t want to be in.

This article also appeared on Medium here.

Recent Posts

White Boy Problems

Risk Factor: The Truth about Dares

The Unspoken Messages of Dress Codes: Uncovering Bias and Power

7k

7k

10k

10k

Follow

Follow

April 4, 2017

Risk Factor: The Truth about Dares

This originally appeared on Rosalind’s Classroom Conversations on ADL’s webiste here.

Risk Factor: The Truth about Dares

By Rosalind Wiseman

“I dare you…”

Who doesn’t remember that from adolescence? At Cultures of Dignity, we’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to take a risk because taking one can be a great learning experience. And then a mom asked us these really good questions: I dare you to hold your breath, which can lead to the choking game. I dare you to chug this, take this pill, drink these shots, jump off this cliff, and the list goes on. How to do you prepare your kid to know what’s a healthy or reasonable challenge and when it crosses the line into scary and dangerous territory?

Here’s a quote from a high school student that makes it all too real:

One kid lit his hand on fire with hand sanitizer. Then the next kid lit his whole back on fire and got second degree burns.

We accept dares and bets for many reasons—to show our loyalty and connection to a group, prove our courage or because it’s easier than facing people’s mockery or name-calling if we refuse. But what this always comes down to is risk taking — questions about when is it worth taking a “risk” and how to define risk in the first place.

So let’s take a step back and list some “risks:”

Changing your music playlist while driving

Climbing onto the roof of a building with friends

Playing a drinking game

Getting into a car with too many people

Rubbing hand sanitizer on your skin and lighting it on fire (as above)

Voicing a minority opinion in a discussion

Sending a nude picture to a person you have a crush on

Before we lecture young people about their lack of impulse control, making a mistake that could ruin their lives forever or bowing to peer pressure, it is important to appreciate the different types of risk and people’s motivations.

Before we lecture young people about their lack of impulse control, making a mistake that could ruin their lives forever or bowing to peer pressure, it is important to appreciate the different types of risk and people’s motivations.

Most of us can talk ourselves into doing things we have no business doing. Why?

We hope for the best and we don’t want to think that the worst outcome is a possibility. It’s what most of us do when we drive and look at our phones. It’s why teens send nude pictures to people they like. We convince ourselves that we won’t get into an accident because we haven’t yet and people won’t share or use nude photos against us.

We believe we have a larger problem. It’s about to be curfew and a 15 year old needs a ride home but the only ride available is to get into a car with eight people that fits five. It’s only a ten minute drive so he’ll take the risk that there’s no seat belts.

We need to demonstrate some kind of power that will impress our peers. For some young people, having a high tolerance in high school is impressive. But an 110-pound girl who is willing to go shot for shot against a 200-pound guy, even if that means she passes out on the couch fifteen minutes later, is now more vulnerable to a spectrum of bad things happening to her like people taking pictures of her and posting them online or sexual assault.

We want to embrace our inner stupid with other people. That seems self-explanatory but here’s a good example.

If you’re speaking to young people about this, avoid the cliché. As in, “Don’t let those people make decisions for you. If they jumped off a cliff, would you?”

Instead, here are a few suggestions:

When you’re hanging out with a group, you should have at least one person there you really trust.

And speaking of trust…trust yourself. You’re smart. If that little voice is going off in your head, listen to it. Certainly trust that voice more than someone who is telling you not to listen to it.

If you are in a situation where people’s safety is at stake or the people are motivated to humiliate another person, I want you to have the courage to ask yourself: What risk feels greater? Standing up to the people or going along with what’s happening? Why? Imagine yourself 24 hours in the future…what would your future self have wanted you to do in that moment?

If you’re talking to someone after the fact, stay away from “WHAT WERE YOU THINKING?” Instead, ask them four questions and try your hardest not to come across as super judgey.

Are you ok?

Was it worth it?

Was there any point when you felt this wasn’t a good decision? Can you describe that moment or how you were feeling?

Is there anything you need to do or say to anyone because of what happened?

But there are risks worth taking.

Speaking out respectfully to voice a different opinion is essential to real dialogue and intellectual diversity. So is speaking out where someone’s physical or psychological safety is threatened. Ironically, these kinds of risks can feel most scary, even though the reality is that not speaking out can have the most negative and long lasting consequences on both individuals and our communities.

And that’s what adults are supposed to do for young people. Ask compelling questions that encourage self-reflection and the ability to understand what is motivating one’s actions. Imagine what happens when we empower a young person with that kind of knowledge.

That’s a risk worth taking.

Recent Posts

Risk Factor: The Truth about Dares

The Unspoken Messages of Dress Codes: Uncovering Bias and Power

The Truth About “Diversity”

7k

7k

10k

10k

Follow

Follow

March 28, 2017

The Unspoken Messages of Dress Codes: Uncovering Bias and Power

This post originally appeared on Rosalind’s Classroom Conversations on ADL’s website here.

The Unspoken Messages of Dress Codes: Uncovering Bias and Power

A few days before I started sixth grade at a private school, I went with my mother to buy uniforms. While she beamed, I miserably pulled the green and white striped dress over my head. I clearly remember the looks from people when I wore that uniform in “public.” It felt like I had a sign above my head that said, “I’m rich and a snob.”

My mother, like many parents to this day, believed that uniforms were the answer to stopping social competition among students and contributing to an overall positive school atmosphere. But for the twenty years I’ve been teaching, I’ve learned that a school’s dress code is much more than what it appears. It is the articulated expectations and enforceable rules created by an educational institution to reflect what it wants to “see” in its students and how it balances safety, unity and the individual rights of its students.

Before I go on, let’s articulate the standard arguments to support school uniforms and dress codes:

Sets a standard for students that learning environments should be given respect and prepares them for a professional environment as adults.

Contributes to students’ self-respect.

Decreases materialism and social competition.

Stops children from wearing clothes that are offensive or promote illegal or unhealthy substances like drugs and alcohol.

Contributes to school spirit and unity.

On its face, all of these goals are reasonable. But clothes and appearance have always been symbols of how an individual belongs within his or her community—or their opposition to that community. And a school may have good intentions but the way dress codes are enforced can mask double standards, insensitivity and bigotry. As an educator, if your school has any kind of dress code, it’s critical to understand the code’s complexities and your responsibilities (no matter what you personally think) and to respectfully enforce it while understanding students’ overall right to be treated with dignity and to self-expression. To do this, here are my best suggestions:

Understand the role of socioeconomic class

Dress codes are often markers of a student’s socio-economic status.

Wealthier, more “traditional” schools often have dress codes that represent the privileged world they are a part of or their families aspire to attain. Middle class or more “liberal” schools have informal dress codes to increase the safe and appropriate environment of the school (how “safe” and “appropriate” are defined can be the source of misunderstanding and inequities). Many lower income schools have uniforms because it’s assumed that students come from low performing schools and they need uniforms for the students to take the learning environment seriously.

Get beyond the easy answers

Uniforms aren’t the magic bullet to stop the “fashion show” competition between students. People know who has more money relative to others, either because the student boasts about it or other people talk about it. If it’s important to students to show how much money their family has, they will figure out a way to show it—from their headphones, smart phones, computers, shoes or what cars their parents drive.

Avoid power struggles

Power struggles with students about any topic are losing situations for everyone. They also go against best educational practices. Adolescents seek out challenges, are often acutely aware of power imbalances in relationships and have intense emotional reactions to those imbalances. We can’t be shocked or take it personally when a kid shows up wearing something inappropriate. What we have to do is model how to respectfully speak to someone who challenges us.

Here are some guidelines.

Ideally communicate non-verbally. For example, if someone is wearing a hat in the hallway, catch their eye, touch your hand to your head. Smile and raise your eyebrows.

If they don’t get the hint, say, “Hey I need your help with something. Can you come over here for a moment?” Your tone is light but directive. When you have some privacy tell them specifically what they’re wearing that’s against the dress code.

If the offending clothing could be construed as a political statement, ask them about it. “I’d like to know more about the shirt and why you wanted to wear it.” Then, if the message they’re wearing could come across as degrading to others, share your opinion about its possible impact on other students.

If it’s endorsing a drug or alcohol message, ask them why they want to wear it. Share your concern that the student becomes a walking advertisement.

If you are a teacher and a student complains to you about another teacher always getting them in trouble for being out of dress code, here’s what you can say to the student.

If someone talks to you about being out of dress code, do what they say. If you feel that they have been rude to you, I still want you to do what they say but then tell me and/or tell the administrator you trust the most. But if you’re genuinely confused about why, or what you’re wearing is important to you and it’s not communicating something rude or degrading about someone else, you have the right to respectfully ask why you are in violation. If you feel strongly about this, you can research your rights about freedom of expression in schools and bring that to the administration. You may not get what you want but it’s important to know your rights and I will support that.

Understand how gender affects how the dress code is applied

The way boys and girls get in trouble for violating dress code is different and girls are disproportionately targeted for disobeying it. In addition, young people who don’t conform or challenge gender norms can also be easily targeted. The question needs to be asked: If a student does not conform to traditional gender roles in their clothing, does that truly contribute to an unsafe learning environment or is he or she exposing the intolerance of others? Whose right is more important to protect—someone’s right to be themselves that doesn’t hurt other people or other people’s bigotry?

Boys most often get in trouble for wearing clothes that are “disrespectful.” When you ask adults to give examples of what this disrespect looks like, the response is almost always, “baggy pants worn down to their knees.” Or they use the word “urban” (i.e. stereotypical black) although I’ve heard the word “ghetto” used as well—which is clearly racist. Far too many adults start the interaction with boys by using their adult power to dominate them and any resistance is seen as defiance and cause for punishment.

In contrast to boys, girls often get in trouble for presenting themselves as too sexual. Girls who go through puberty earlier and/or are more developed are also disproportionately targeted. Yes, a girl with a developed body can be distracting but that doesn’t mean the students around her should be held to such a low standard that they aren’t expected to treat her respectfully. Adult reaction to these girls can be extremely counterproductive if they think shaming the girls for being “slutty”* is the appropriate response. Further, it contributes to the dynamic where adults teach girls and boys that girls are responsible and therefore to be blamed if others say and do sexually degrading things to them. It’s a mixed message and a missed educational opportunity to not acknowledge and educate girls and boys about the constant hyper-sexualized messages girls receive and how that influences what they choose to wear.

No matter what you do in a school or who you are (I believe men can and should have these conversations), here’s a suggested script to speak with girls:

This is difficult to speak about with you but it’s important to me that I do. You are getting into trouble for violating the dress code and we have to address that. But way more important to me than the dress code is you. You are a smart young woman with a lot to contribute to this world. Like all young women, you’re growing up in a world that dismisses your opinions and rights by trying to convince you that the most important thing about you is your physical appearance. Obviously, you are so much more than that. I want you to be proud and comfortable with how you look. But I also want you to be proud and comfortable about who you are beyond that. Can you think about what is most important in how you want to present yourself? Can you put your clothes that you like and that are within the dress code on one side of the closet and your other clothes on the other side?

Creating a positive environment

As a teacher or school administrator, I know that one of your priorities is to set up a positive environment in which young people can and want to learn. It is not in anyone’s best interest to make students feel uncomfortable, angry, awkward or ashamed of who they are. My advice is to be clear about what your dress code is, why the rules are in place and have a thoughful justification for them. Then communicate that to students with precision, strength and a well-articulated rationale. Be consistent in your approach. And when the dress code is violated, be kind, accepting and make sure students understand why. They may not agree but they will feel respected and hopefully that respect will be returned.

*Note that while this word is used frequently, it highlights the inherent bias in labeling women’s sexual identity.

Recent Posts

The Unspoken Messages of Dress Codes: Uncovering Bias and Power

The Truth About “Diversity”

What We’ve Been Up To // March 2017

7k

7k

10k

10k

Follow

Follow

March 20, 2017

The Truth About “Diversity”

Marley has been interning with our team since December and this is her first published piece. Marley is a 16 year old junior at Fairview in Boulder, Colorado. She plays volleyball, basketball, and runs track and wants to pursue a business career in college.

Below are her powerful words about how we can change the conversation around diversity.

The Truth About Diversity

By Marley Martin

Recently, a ‘Diversity Day’ was held at my school and immediately people were figuring out ways to avoid it. No one wanted to listen to our administrators’ comments about acceptance or inclusion; we just wanted to get on with the school day. I’ll admit, I didn’t want to attend the assembly either. It seemed like a waste of my time because I assumed they were only going to talk about race and being an African American 16 year old girl in Boulder, I figured there wasn’t much I could learn about diversity here. Although well intentioned, a diversity day at my primarily white high school didn’t seem beneficial or necessary. This assembly wouldn’t change the fact that I’m different from my peers in ways they’ll never be able to understand, and having white students trying to teach me about diversity just seemed artificial. Moving to Boulder from Washington D.C. opened my eyes to the many differences between parts of the country. I didn’t feel as isolated before I moved, because when I looked around I saw people like me. I was a minority, but I wasn’t in the minority. My high school has so few students of racial minorities that our rival school mocks us at athletic events by chanting, “I’m rich, I’m white, I must be a knight” (our mascot is a knight of course).

However, the assembly surprised me because it made me appreciate the hidden diversity of my school. Instead of the assembly only being about race, students shared a range of experiences from struggling with their sexuality to having an abusive family member; issues that are invisible when those students walk down the school hallway.

These stories helped us recognize and appreciate the differences in our community. But, only a few hours after the assembly had ended, it appeared that nothing had changed. Once again I heard familiar phrases like, “You’re such a fag” or “Yeah, that’s retarded” hurled around as everyday chatter at my school. Hearing these hurtful words made me reflect on the culture of my school and how necessary, yet difficult, change is. Not even one day had gone by, and people were already using hateful speech without a second thought.

Hearing words like “gay” and “slut” make me flinch, but I’ve never been willing to do anything about it. I try to convince myself that when I hear even my closest friends say them, that they don’t ‘mean’ to use such derogatory language, or it’s just habit. After the assembly, I began questioning the environment around me. What has conditioned people to use words like this? Why haven’t we been able to stop it? Why don’t I stop it?

I have a few thoughts about this. First, it’s habit. People are accustomed to saying and hearing these words as insults. When they aren’t criticized or called out for their words, it’s seen as okay and that nothing will be done about it.

Second, what’s currently being done in schools isn’t enough. It’s the standard for high school students to be herded into a gymnasium, an auditorium, or a classroom, and sit down to talk about “accepting one another” and “being inclusive.” Students have this same message thrown at them so many times they’ve learned to tune it out because what they learn in the presentation isn’t connected to their everyday lives. We assume that yes, even though this language is wrong, this doesn’t really happen in my school, or I’m not really hurting anyone by saying these kinds of things.

After the presentation ended, my school broke into small discussion groups. My group was reluctant to participate past the bare minimum, and for good reason. In a group full of strangers, it can be extremely difficult to talk about the hard things, the things that make us uncomfortable. Having the tough conversation with our peers, and even our friends, can be almost impossible in the small bubble of high school. What I’ve realized is that talking about these subjects is a process, not just a presentation. This issue can’t be fixed in an hour of discussion.

Just trying to figure it out is a step in the right direction. As an intern with Cultures of Dignity, we discuss these issues and how to make them more relevant for students like me. We get to think about the conversation around diversity differently so we don’t revert back to the same habits.

Separating the discussions we have in the classroom from what we choose to do outside the classroom contributes to the issue itself. One student leading the Diversity Day suggested writing down every time we made a judgement about someone so we noticed our own judgments. I agree. We need to integrate this process into how we think all the time, so when we hear these words in school, we don’t just brush it off and act like nothing happened. Noticing our judgments, and deciding what to do about them, is the first step to really change this problem. And if we can do that–diversity days will be worth it.

Recent Posts

The Truth About “Diversity”

What We’ve Been Up To // March 2017

No Words // Guest Blog Post

7k

7k

10k

10k

Follow

Follow

March 15, 2017

What We’ve Been Up To // March 2017

At Cultures of Dignity, we have been busy over the past month. From keynotes at fundraisers, to eating chips and guac with high school students while intensely debating the use of social media in our lives, here are some highlights!

// What we’ve been doing

GALs Luncheon

Our entire team, including our amazing high school intern, Marley Martin, attended the annual luncheon for the Girls Athletic Leadership School in Denver. Rosalind had the honor of delivering the keynote and discussed the values of GALS as seen in our own communities

“GALS is a school like many in this community and across the country that stand for the belief that all children have the right to feel safe and welcome in schools and it is our responsibility to do everything we can to make that a reality.

“GALS is a school like many in this community and across the country that stand for the belief that all children have the right to feel safe and welcome in schools and it is our responsibility to do everything we can to make that a reality.

We believe reaching in towards each other and listening when we are angry strengthens our communities

We believe that intellectual diversity and robust civil dialogue is how education happens.”

Silver Creek High School Abash the Past sponsored Poetry Slam

Silver Creek, a local high school, holds monthly poetry slams during their lunch hour to give students a chance to find their voice and talk about issues they care about. We attended the Abash the Past themed poetry slam in support of the work Jordyn Monnin’s movement to end slut shaming.

A student stood up for the first time and shared a powerful poem about what it is like to grow up in an immigrant home and how her home “has been invaded by uncertainty” with the recent election. Read Karla’s important words here.

Student reading her poem

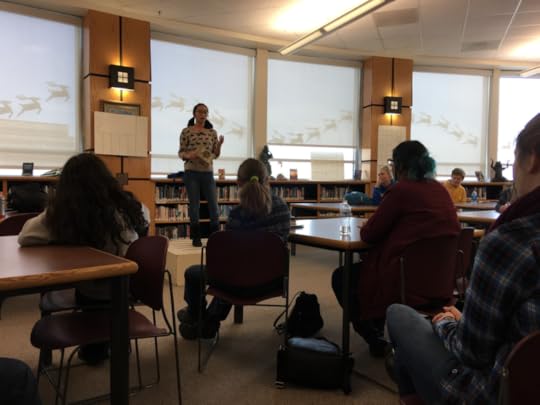

Summit Middle School talk with 8th graders

We had the chance to hang out with 8th graders from Summit Middle School and discuss how the media, adults, and even toys teaches us the unwritten rules of boy and girl world from a young age.

“You need to call out adults in the world who are doing things that are wrong and hypocritical. You have a voice!”

Keynotes

Rosalind keynoted at Evergreen Country Day School in Evergreen CO

Speak SF in San Francisco,

Penn Trafford School District in PA

Zen Parenting Conference in Chicago

Focus Groups

We got together with groups of high school students in Boulder, CO and chatted about all things social media: from unwritten rules of talking to a new guy on snapchat and who to follow on instagram to sending sexual pictures and the power of influencers.

Favorite quotes:

“We get slut-shamed by our own parents if we post bikini shots”

“I’m literally contemplating going to a school because a youtuber I follow goes there”

“I want to scoop my eyes out with a rusty spoon – instagram is so fake it’s unbelievable.”

We are working with our interns to write a couple follow-up articles and will be hosting focus groups with middle schoolers in the upcoming weeks – so stay tuned!

Planning for Owning Up PD Training!

We are offering a day long accredited Owing Up Professional Development Training in Boulder CO on April 29th on teacher mindset and the Owning Up Curriculum— it’s going to be awesome! This is our first time conducting this training in Colorado and we couldn’t be more excited!

The Owning Up training brings concrete strategies to prepare youth to be engaged learners and socially responsible citizens.We are taking the newest approaches and the latest feedback from educators and young people, and redeveloped professional development to provide the skills and expertise that educators need most!

This training is about:

Defining realistic definitions of bullying, by-standing, teasing, drama and social conflict.

Analyzing individual behavior and decision making related to negative group social dynamics.

Identifying dynamics that lead to social conflict

Recognizing the value of a growth mindset for educators as well as the students

Teaching students to effectively intervene in social conflicts with their peers.

Outlining challenges educators have to teach these topics effectively and obtain student buy-in

Learn more about the training and register here!

// Issues we have been thinking about

Trans community

The most important lesson we can teach our children is that they have the right to be themselves.

Check out the latest news on how transgender young people are affected here

International Womens Day

We wore red is solidarity with the women protesting, striking, and fighting to be heard on International Women’s Day.

We loved the stories of people celebrating around the world featured in the New York Times, below are some favorites.

March 6, 2017

No Words // Guest Blog Post

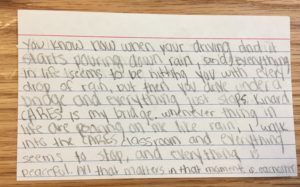

Recently, Rosalind traveled to Penn Trafford School District in Pennsylvania to work with two middle schools and one high school. After her presentation at a local middle school, a student reached out and shared some of her powerful writing. We love featuring student writing and giving young people a voice on issues they care about.

Below is a poem written by 13 year old Rebecca, an 8th grader at Penn Middle School.

Recent Posts

No Words // Guest Blog Post

Meet Emily // Interview With Our Newest Intern

Call Me Perfect // Supporting Awesome Work

7k

7k

10k

10k

Follow

Follow

February 17, 2017

Meet Emily // Interview With Our Newest Intern

Emily is a junior at Tara High School in Boulder, CO. She is working with the Cultures of Dignity team to produce and share relevant content! She has experience in leadership programs and is eager to learn and create with the team.

Meet Cultures of Dignity’s newest intern!

Cultures of Dignity: Tell us a little about yourself!

Emily: I go to school in Boulder at Tara High School and I act, write, and bike. I live in Broomfield, with my parents, sister, and dog (Oscar).

CoD: Why did you reach out to Cultures of Dignity to be an intern?

Emily: I wanted to be a part of an organization where the work being done is open, relevant, crucial, and ground-breaking. Cultures of Dignity has all this and more, and I can see positive change happening already.

CoD: If you could have any superpower what would it be?

Emily: I would want to be able to fly!

CoD: What projects will you be working on with CoD?

Emily: I would be creating and sharing content and helping create relationships with influencers.

CoD: What is an issue you see in schools you want to fix?

Emily: Overwhelmingly negative attitudes are something I notice a lot, and I want to show people how frustration can be channeled into productivity. Also, creating an environment in which everyone is comfortable being themselves is something that needs to be further addressed.

Recent Posts

Meet Emily // Interview With Our Newest Intern

Call Me Perfect // Supporting Awesome Work

The Right to Be Human

7k

7k

10k

10k

Follow

Follow

February 13, 2017

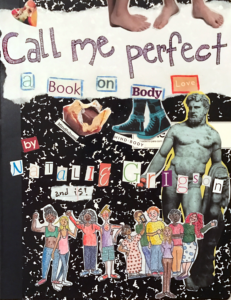

Call Me Perfect // Supporting Awesome Work

Body image, self acceptance, gender identity, and consent are important issues young people are grappling with every day. Natalie Grigson explores these complicated issues in her new book, Call Me Perfect: A Book on Body Love, written for kids and teens. This book – part story, part workbook – is the sequel to Just Call Me Is. This unique little book covers all things body image and includes real body photos. Natalie is working to create a culture of dignity around self love and we are proud to support her message.

Natalie just launched a Kickstarter campaign to make this book a reality and could use your help! Watch her video and check out an excerpt from the book below.

Kickstarter Campaign

You

You’re beautiful.

You’re not too fat,

And you’re not too skinny.

Your skin is just fine (yes, really.)

And even if sometimes you feel like you have to be perfect—you have to go on a diet, you have to be prettier, more handsome, stronger, less gangly, taller, have better ears—whatever—YOU are already perfect, just as you are.

Now, I’m sure you’ve heard these things before—maybe from your parents or a teacher. And I’m sure you’ve heard the opposite before—that you’re fat, ugly, unlovable, not good enough. Maybe you’ve heard it from kids at school, from the messages you get every day from television or magazines, or even from yourself when you look in the mirror.

I know that you’ve heard them before, because all this time, I’ve been here with you—your Inner Self—just listening.

Hello!

I’m Is. Some of you guys might have met me before when I introduced myself in a little book called Just Call Me Is (clever title, I know.) It was an introduction to mindfulness, which don’t worry, I’ll get into plenty here.

This time, though, I thought we’d take a different tack. Because as your Inner Self, I am also the Inner Self of oh, just like, everybody else in the world. See, we are all made up of the same stuff: energy. It’s your soul, your consciousness, The Universe—whatever you want to call it, it’s energy. It’s me. It’s you. It’s that kid in your class that laughs really loud; it’s the girl you think is so pretty that it hurts; it’s everyone.

And as your Inner Self, I know that body image is on your mind A LOT. Just as much as it was on Margery’s mind (who you’ll meet in a minute.) Just as it’s on the kid in your class’s mind, and even on the mind of the prettiest girl in school.

So, you and me—we’re gonna have a talk about it. Don’t worry, no one else needs to read this, or the notes that you make in the back of the book. And don’t worry, I won’t tell anyone that this is something you’re struggling with.

But just know, you are NOT alone. More kids struggle with thoughts like “I am too fat” or “I’m not good looking enough” than anything else. Believe me, I know.

Especially kids like Margery.

And this is how her story goes.

Once upon a time there was a girl named Margery—Okay, okay. I won’t bore you with the intro, because these “Once Upon a Times” tend to end with “Happily Ever Afters,” and that, as we know, isn’t always the case. Now, for those of you who read Just Call Me Is, the name Margery might sound a little familiar. As you’ll remember, she was Tori’s best friend in England, before Tori moved away.

And for those of you who didn’t read Just Call Me Is, and have no idea what I’m talking about—don’t sweat it. All you really need to know is that while I am your Inner Self, and Tori’s Inner Self, I am also Margery’s Inner Self. So while we followed Tori’s story when she moved off to New York, there was still a story going on in England with Margery.

And so that is where we’ll begin.

Margery Tomlinson

Margery Tomlinson grew up in a small town several hours outside of London. Her mom and dad split when she was just four-years-old, so like many kids Margery’s age, she grew up mostly with her Mom. (Her dad had moved to Connecticut when she was just six.)

When we last saw Margery, she and her best friend, Tori were just entering fifth year—when suddenly, Tori moved away to New York City, because her dad had gotten a new job.

It was hard for Margery; harder than she let anyone believe. Because, you see, Margery liked to play things cool; stay tough. She didn’t like to ask for help. And she certainly didn’t want anyone to see her cry. (Sound familiar?)

But cry she did, for several weeks after her best friend moved away. She spent much of her fifth- year, sitting by herself at lunch, eating cookies, reading at home, and hanging out with her Mom—whose main interests included pouring over fashion magazines, exercising constantly, and dating men half her age.

But we’ll talk more about Cynthia later.

Our story truly begins several months after Tori left town: when Margery started secondary school. Or, as you in the U.S. might know it: Middle School.

Dun… Dun… Dun…

More about the Author

[image error] Natalie Grigson was born and raised in Austin, Texas by a pack of surprisingly well learned wolves. From them, she gained her love of reading, writing, and, of course, shabby chic interior design. (Just kidding. Wolves are much more partial to modern decorating.) These days, Grigson works full-time as a spinner of tales – mostly Young Adult and Middle Grade – and mostly from home, though where that is seems to change from season to season.

She is the author of such books as the Peter Able series, The Woods, Matthew Templeton and the Enchanted Journal, and Just Call Me Is.

Recent Posts

Call Me Perfect // Supporting Awesome Work

The Right to Be Human

When do Teachers Stay Neutral? // ADL Article

7k

7k

10k

10k

Follow

Follow