Rosalind Wiseman's Blog, page 19

June 28, 2018

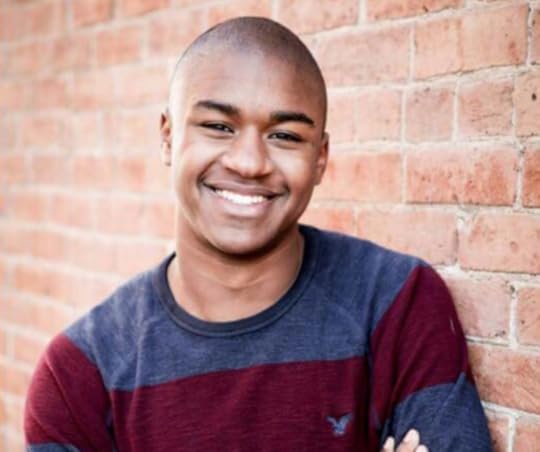

Meet Tré! Interview with Summer Intern

Tré Garnett is a rising sophomore at University of Oregon where he is studying Psychology and Political Science. He will be interning at Cultures of Dignity to help with research and videography during this summer.

Meet Cultures of Dignity’s Newest Intern!

Cultures of Dignity: Tell us a little about yourself!

Tré: I was born in Austin, Texas and grew up in Fort Collins, Colorado. I am a rising sophomore at University of Oregon, studying psychology and political science. My hope is to pursue research regarding demographic and political trends in order to foster discussion of how to create healthier social environments for all.

Cultures of Dignity: Why are you working with Cultures of Dignity this summer?

Tré: I hope to explore the social dynamics which exist within today’s youth since issues of inclusion and diversity have become especially poignant in recent years.

Cultures of Dignity: If you could have any superpower what would it be?

Tré: Nothing would be cooler than being able to produce any music at any time. I could walk into any room with theme music and I wouldn’t have to spend any more money on music for my phone.

Cultures of Dignity: What projects will you be working on with CoD?

Tré: I will be assisting in efforts to research ongoing social trends as well as providing videography and outreach support for CoD.

Cultures of Dignity: What is an issue you see in schools you want to fix?

Tré: I want education to adapt and help students have more productive and critical conversations around diversity and inclusion. We are seeing a rise of politically active generation but I want schools to keep up.

Recent Posts

Meet Tré! Interview with Summer Intern

What’s The Difference Between Dignity and Respect?

Meet Keila! Interview with Summer Intern

Learn about how we work with young people:

STUDENT VOICE

The post Meet Tré! Interview with Summer Intern appeared first on Cultures of Dignity.

June 26, 2018

What’s The Difference Between Dignity and Respect?

Charlie Kuhn is the CEO & Co-Founder of Cultures of Dignity. Charlie was asked to share with us how we can reframe and better understand what it means to strive for cultures of dignity for Artemis Connection’s blog, originally posted here.

What’s The Difference Between Dignity and Respect?

By Charlie Kuhn

“How could you even think this is a good idea?”

“You don’t know what you’re talking about!”

“This has to be fixed immediately!”

How do we learn to manage our responses to this? Most of us aren’t in a place where we can handle this quickly and effectively. We react. We get emotional.

Civic dialogue and critical thinking in moments of conflict underpin a culture of dignity. But how do we get there? One way is to understand the reasons why this is so challenging. What is misunderstood? What’s going on that isn’t seen but felt?

We can start with getting clear with the meaning of words and how they’re used.

Dignity and respect are words with profound meaning but they’re also words that are usually heard when we are being lectured at or corrected. So it’s only normal that we struggle to truly understand or internalize their significance.

Here are our definitions at Cultures of Dignity:

Dignity: From the Latin word dignitas, meaning “to be worthy.”

As in: All people have the right to be recognized for their inherent humanity and treated ethically. Dignity is a given. You just have it and no one can take it away.

Respect: From the Latin word respectus, meaning “to look back at.”

As in: showing admiration for someone because of their abilities, qualities or achievements. Respect is earned. You are respected by others for what you have achieved, experienced and how you have handled yourself as you have achieved accomplishments.

The problem is we use respect in two distinctively different ways: Recognizing a power or status difference between people or recognizing the value of a person. When it comes to a relationship, we commonly frame being respectful as being polite, obedient and following the rules. In this context, questioning the rules or challenging the person enforcing the rules is often perceived as defiant, rude, disrespectful and subject to punishment.

The questions then become:

Should you respect someone in a position of authority who abuses power?

Should you respect someone who doesn’t treat others with dignity?

Even if they’re older than you?

Even if they have more seniority than you?

Even if they have more experience than you?

If dignity is a given that can’t be taken away, what does it look like to treat someone you don’t respect with dignity?

If we use dignity as our anchor and ground our work in the belief that every person has value, then we can separate people’s abusive actions from their essential humanity. For example, there may be a boss at work who belittles, bullies, or embarrasses people under them in front of others. The boss does not need to be respected based on their behavior but they need to be treated with dignity. It may look like the same thing—treating the person with respect versus treating that person with dignity but it is an important distinction. Respect acknowledges the behavior while dignity teaches the importance of civility and humanity.

The same concept can be applied to a peer situation. Co-workers get rightfully frustrated when colleagues are undermining or take credit for work they didn’t do. We want revenge or to be recognized for their contribution. We want the right to be pissed at this person. If we give ourselves the right to be angry and not take our feelings away. We don’t have to be friends and we don’t have to respect their actions. We don’t even have to like them, but we do have to treat them with dignity.

This distinction between dignity and respect allows us to not be driven by fear, anxiety, or hold resentment and somehow sabotage the person that acted in a troubling way. Surprisingly, separating respect and dignity enables you to be better at your job and not bring the “How could you even think this is a good idea?” line home with you.

Recent Posts

What’s The Difference Between Dignity and Respect?

Meet Keila! Interview with Summer Intern

Meet Micah! Interview with Summer Intern

The post What’s The Difference Between Dignity and Respect? appeared first on Cultures of Dignity.

June 21, 2018

Meet Keila! Interview with Summer Intern

Keila is a rising senior at California Polytechnic State University where she is studying entrepreneurship. This summer she will be interning with Cultures of Dignity, focusing on marketing and branding.

Meet Cultures of Dignity’s Newest Intern!

Cultures of Dignity: Tell us a little about yourself!

Keila: Hello! My name is Keila and I was born and raised in Boulder, CO. Currently, I am attending Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo, CA where I am focusing on business and design. I am passionate about building relationships, constantly learning, and good food (especially tacos).

Cultures of Dignity: Why are you working with Cultures of Dignity this summer?

Keila: About five years ago, I met Rosalind and Charlie in a focus group for Queen Bees and Wannabes. Throughout the following years, their work continued to resonate with me. In January, I reached out to them and am now super excited to be a part of the team!

Cultures of Dignity: If you could have any superpower what would it be?

Keila: I would choose the superpower of teleportation. It would be so much more time efficient and it would be better for the environment! And I could avoid traffic on Broadway during rush hour.

Cultures of Dignity: What projects will you be working on with CoD?

Keila: I will be primarily working on marketing, branding, and graphics for CoD. I will also assist in administrative business aspects (analytics, etc.)

Cultures of Dignity: What is an issue you see in schools you want to fix?

Keila: I am concerned with the way students are taught to view failures as defeat. Instead, I think failures should be embraced as an important, humbling learning experience. Promoting this growth mindset empowers students to persevere and overcome challenges.

Recent Posts

Meet Keila! Interview with Summer Intern

Meet Micah! Interview with Summer Intern

Meet Taylor! Interview with Summer Intern

Learn about how we work with young people:

STUDENT VOICE

The post Meet Keila! Interview with Summer Intern appeared first on Cultures of Dignity.

June 19, 2018

Meet Micah! Interview with Summer Intern

Micah is sixteen years old and is going into his sophomore year of high school at Boulder High School. Micah has lived in Boulder Colorado for almost all of his life, but loves to travel the world. This summer, Micah will help with the social media presence of Cultures of Dignity and The Guide.

Meet Cultures of Dignity’s Newest Intern!

Cultures of Dignity: Tell us a little about yourself!

Micah: I am 16 years old and I am going into my sophomore year at Boulder high school. In my free time, I play soccer competitively for Boulder High and for a local club team. I also enjoy listening to good and new music and spending time with my two brothers and my friends.

Cultures of Dignity: Why are you working with Cultures of Dignity this summer?

Micah: I am working with Cultures of Dignity this summer to help other students through tough times, and improve the school climate around Boulder and for students across the country. Also, I want to gain experience and learn new ways I can offer resources to students that may need help.

Cultures of Dignity: If you could have any superpower what would it be?

Micah: If I could have any superpower, I would want the ability to fly so I could be able to travel around and see the world much much faster.

Cultures of Dignity: What projects will you be working on with Cultures of Dignity?

Micah: This summer, I will primarily be working on The Guide, and the social media accounts for The Guide.

Cultures of Dignity: What is an issue you see in schools you want to fix?

Micah: One of the biggest issues in schools I want to fix is the lack of conversations about difficult subjects between people in positions of power and students. Most of the time, it is just teachers telling students how to act and what to think about certain topics rather than letting the students express how they feel. I want to fix this issue because it creates a lack of communication and prevents the necessary changes from happening in schools.

.

Recent Posts

Meet Micah! Interview with Summer Intern

Meet Taylor! Interview with Summer Intern

Telling An Adult Isn’t So Easy

Learn more about how we work with young people:

STUDENT VOICE

The post Meet Micah! Interview with Summer Intern appeared first on Cultures of Dignity.

June 14, 2018

Meet Taylor! Interview with Summer Intern

Taylor is a rising freshman at Colorado State University, and will be majoring in Journalism & Media Communication. She is interning with Cultures of Dignity for the summer to share her perspective on issues that youth face through the blog and social media.

Meet Cultures of Dignity’s Newest Intern!

Cultures of Dignity: Tell us a little about yourself!

Taylor: Hi, I’m Taylor! I’ve lived in Longmont, CO my whole life and am excited to attend CSU in the fall. I love being outside and active whether it be golfing, hiking, or running. I am also a singer-songwriter performing in the local community.

Cultures of Dignity: Why are you working with Cultures of Dignity this summer?

Taylor: I wanted to work with Culture of Dignity because I support their vision of creating environments of dignity, and I wanted to learn more about how I could contribute to their vision. I think it’s important that relationships between adults and teens are open-minded and all-perspective oriented.

Cultures of Dignity: If you could have any superpower what would it be?

Taylor: I would love to have super speed so I can travel anywhere in the world at a moments notice. The first place that I would carry myself with my super speed would be the beach, and then I’d go back to the mountains in Colorado the same day!

Cultures of Dignity: What projects will you be working on with Cultures of Dignity?

Taylor: I’ll be working with the blog and writing, and I’ll also be helping out with social media content.

Cultures of Dignity: What is an issue you see in schools you want to fix?

Taylor: An issue in schools that I see is an absence of support and help for students dealing with mental health issues. Also, I would like to see schools become more sustainable in their practices, and initiate a zero waste program.

Recent Posts

Meet Taylor! Interview with Summer Intern

Telling An Adult Isn’t So Easy

What To Do When You’ve Tried Everything & The Bullying Won’t Stop

Learn more how we work with young people:

STUDENT VOICE

The post Meet Taylor! Interview with Summer Intern appeared first on Cultures of Dignity.

June 7, 2018

Telling An Adult Isn’t So Easy

By Rosalind Wiseman

In schools, we encourage young people to report when they see a classmate break a rule. “If you see something, say something” is our constant advice. This could include observing a peer make a racist or sexist remark about someone, physical aggression and bullying, cheating or bringing contraband (e.g. Juuls or other drugs) to school.

Yet, there is tremendous pressure on students not to report problems. This leads to reluctance to report, which is made worse by the way adults tend to talk about reporting as an easy decision for young people to make.

We must acknowledge the dynamics that make reporting so challenging.

We need to remember that there is always a context in which a student reports the problem, when they report it and why. And, just as importantly, there is always context for the student who broke the rule—how will they respond to us and to the student reporter they may blame for “getting them in trouble.”

If we don’t understand context, then we won’t be able to effectively address and discipline the rule breaker or protect the child who came forward.

And it’s just a reality that some students are better at breaking rules and getting away with it than others.

So let’s take a step back and look for patterns in order to understand context.

In schools, there are always parallel justice systems operating: the school’s and the students’. The school’s “justice” system usually entails taking a report, deciding to what extent the report is credible and then, to varying degrees, imposing consequences on the student who broke the rule.

Meanwhile, there is a different but often more socially powerful justice system among the students. This system is based on group norms among young people and a set of specific “rules” about when a student is right or justified in reporting a problem to adults.

Then, the dominoes of public opinion go into motion. First, when students find out that one of their peers reported on another student, someone is going to put time and energy into discovering who “snitched.” Shortly thereafter most of the other students know who is in trouble. And a while after that, a general consensus—typically spread online—is developed about whether the reporter is “in the right.” Rumors, misinformation, and gossip spread about who is right and who is wrong.

How do students assess if the student who reported made the right decision?

Did the person who committed the original act hurt others?

If the person hurts others, it’s easier for public opinion to decide that reporting was the right course of action. Bullying, bias and other forms of extreme social aggression more easily fall into this category. But there are a few details that make this more complicated in the students’ minds.

If the students know that the conflict “went both ways” or the reporter was directly involved in the “drama,” the reporter will lose credibility among their peers. In addition, the social status of the person who got caught and the likeability of the reporter often guide the students’ decisions, often without them even realizing it. In addition, students often have an unspoken benchmark of what is considered reportable and what isn’t. For example, what’s the level of “meanness” that must be reached for a student to justify reporting, instead of handling it on their own? Does intent matter? Does the person reporting need to be convinced that the actions were intentionally hurtful? Because most teens I know believe intent does matter, they think reporting should be limited to the knowledge that the person knew the impact of their actions on the person they hurt and deliberately did it anyway.

As adult facilitators, our job is to break down some of these norms. If someone is being hurt, it is the adult’s job to help determine intent. But in the meantime, the hurtful behavior has to stop. And the takeaway here is just because it’s common doesn’t make it right.

Did the young person’s action hurt themselves?

Teens aren’t just reporting about another student’s negative social behavior. They are also reporting when they know a peer is doing something dangerous or illegal. From an adult perspective, the decision is clear: the student is making unhealthy decisions and needs help. But it’s not often that clear-cut to students because they are weighing other factors. For example, is the student hurting themselves in similar ways to their peers so the behavior looks “normal” (i.e. not reportable)? What if they see that person on social media shortly thereafter looking fine? Most young people, like all of us, are looking for ways to downplay the problem because reporting can be so tricky. They ask themselves, “What if I’m wrong? What if I’m overreacting? What if I report and the adults in charge handle it badly? What if I become labeled a snitch?” These are all understandable questions that can be addressed in advisory sessions or other classes where these issues are typically discussed.

What’s the punishment?

While the school may impose consequences and hopefully effectively address the problem, when the incident becomes public, students also pass judgment on the “politics” behind the decision. They come to their own “verdict” and it’s usually either social affirmation or exclusion. Whoever is perceived to be in the right is more likely to be visibly supported by their peers. Whoever is wrong can be socially isolated and excluded.

What do we do?

We have to admit that this is messy. All of it. People have different standards about what bothers them and everyone has the right to their feelings; if they don’t feel safe or believe someone else isn’t, that’s how they feel no matter what others think. Every situation is different so students need the opportunity to talk about the complexity of these situations so they are more prepared when they face a problem of their own.

Discussion prompts

My teen editors and I came up with a hypothetical situation to discuss with your students so you can ask them what they would do if faced with this scenario:

A couple of times you have seen this kid slap the legs of this other kid when he walks by. You don’t know either of them that well but you can see that the kid getting slapped hates it. What if there is a teacher in the hallway but they don’t do anything about it and you’re not sure why? Who do you tell? Do you include the teacher who usually witnesses what is happening? Why or why not?

At the end of the discussion, it is important that the teacher or facilitator acknowledge how confusing and complex reporting can be. From a student’s point of view, it is understandable to not want to report. On the other hand, if students don’t report, the adults in school can’t help. These conversations are a way for students to decide for themselves what their personal reporting criteria are. When faced with a similar situation, they are more prepared and can make better decisions they can be proud of and that will ultimately make the school and all the students in it safer.

This article originally appeared on Rosalind’s Classroom Conversations on ADL’s website.

Recent Posts

Telling An Adult Isn’t So Easy

What To Do When You’ve Tried Everything & The Bullying Won’t Stop

Thank You To The People Who Stick By Our Children

The post Telling An Adult Isn’t So Easy appeared first on Cultures of Dignity.

May 18, 2018

What To Do When You’ve Tried Everything & The Bullying Won’t Stop

It’s more common than we may like to admit. Sometimes you have a group of students who are constantly having problems with each other. You try everything and nothing seems to work.

When you are frustrated that everything you’re trying to make a situation better isn’t working remember a few things: You care about your students and you have the will and capacity to figure out a solution. You are allowed to be frustrated by this situation because it is frustrating. You’re even allowed moments of not liking the students who are making this situation so challenging.

Take a Step Back

If you’re saying to yourself, “I’ve tried everything,” take a step back. This phrase means that you have gotten to a place where it’s very hard to self-reflect thoughtfully or creatively come up with new ideas.

First, inventory what you know. Write down specifically, with as much detail as you can remember, what you mean by, “I tried everything.” When you’re done, take a walk around the block or the school, somewhere so your brain can think creatively. Come back and try to write down three insights about why you think your previous strategies haven’t been effective and what you can do to address those obstacles.

Here are some sample questions you can ask yourself:

What was my reasoning for implementing the strategy I chose?

When did I implement this strategy? Not only the date but what was happening in the school?

What was happening in my classroom that week?

Did I respond emotionally (out of fear, frustration, etc.)?

What are the students doing right before they come to my classroom? For example, if they are coming back from lunch or recess something could have occurred then that impacts the students’ behavior in my class.

Try the following exercises to look at your situation from a different perspective:

Write down a few sentences that clearly define what you want to change in this situation or between the students who are having a problem.

Observe the group when they aren’t your responsibility. Watch them before school, at lunch or ask another teacher who has these students if you can observe their class.

Ask a colleague to sit in the class while you teach. They can sit in the back of the room and bring their own work; you need a second pair of eyes and ears to pick up what you’re missing. Debrief after class and come up with strategies together. And get over any feelings of failure or embarrassment that you’re asking for help or admitting that things aren’t going great in your class. It happens to everyone. If a colleague says it’s never happened to them, they’re deluding themselves.

Talk With the Students

When you’ve done your inventory and observed the students, schedule a time to meet with the aggressors (one at a time) and then say in your own words:

“I really want you in my class because [insert something positive about the student here]…but what’s going on with you and x student isn’t acceptable to me because… Just like I would defend your right to be in my classroom and be treated with dignity, I will do the same for this student. Is there anything I should know about this situation that would help me understand what’s going on? (Whatever the response it doesn’t justify the behavior but any background/more information is helpful.) More than getting you in trouble, I am asking for your agreement that you understand why it’s important to stop undermining this student. I want you in this class. Do you think you can do this?

Just so there’s no surprises, although I believe you get what I’m saying and you’re taking it seriously, if this doesn’t change, here’s what could happen as a result…[insert next level of discipline here] I don’t want that to happen but if this continues, you’re limiting what I can do because I have to have a class that’s safe for all of my students. Thanks for meeting with me.”

The bottom line is there isn’t going to be one solution for this problem and it’s probably going to take time. You probably won’t have one “aha” moment with the students where they permanently change their behavior. But if you reflect on how you’re responding to the dynamics between the students and then take the time to really “see” what’s going on between them, you will figure out how to be more effective.

This post appeared on CrisisGo– who provides tools for schools to increase safety awareness, improve rapid response, connect parents and school staff, and improve procedures with comprehensive data.

Recent Posts

What To Do When You’ve Tried Everything & The Bullying Won’t Stop

Thank You To The People Who Stick By Our Children

Dignity vs Respect

The post What To Do When You’ve Tried Everything & The Bullying Won’t Stop appeared first on Cultures of Dignity.

May 9, 2018

Thank You To The People Who Stick By Our Children

This week is Teacher Appreciation Week and we want to help you honor the educators in your life.

We believe it’s good to revisit something about a relationship that’s bothering you, we also believe that you can offer praise or acknowledgment in relationships at any point.

It can be as simple as “Hey, I’ve been thinking about what you did [be specific here] a few days/weeks ago and I want you to know how much it meant to me. Thank you so much.”

During this week, we encourage all of us to acknowledge the hard work of educators– whether that be your child’s teacher, your own mentor, or teacher from your past – and what they have done in our communities to uphold the emotional and physical well-being of our children.

It doesn’t have to be a huge life-changing experience. Your child doesn’t have to come out of the class a completely changed person but helping a tough situation go from 90% bad to 75% bad or seeing them do a more difficult math problem is what this relationship is all about.

So, here’s a mad lib to get you started:

Recent Posts

Thank You To The People Who Stick By Our Children

Dignity vs Respect

Acting Out: How a Theatre Techniques Class Teaches Social Skills

DOWNLOAD THE LETTER

The post Thank You To The People Who Stick By Our Children appeared first on Cultures of Dignity.

April 25, 2018

Dignity vs Respect

Dignity and respect are words with profound meaning but they’re also words that young people usually hear when adults are lecturing them or correcting their behavior. So it’s only normal that they can struggle to truly understand or internalize their significance.

We have to get clear about the words we use so in turn, young people are clear.

Here are our definitions at Cultures of Dignity:

Dignity: From the Latin word dignitas, meaning “to be worthy.”

As in: All people have the right to be recognized for their inherent humanity and treated ethically. Dignity is a given. You just have it and no one can take it away.

Respect: From the Latin word respectus, meaning “to look back at.”

As in: showing admiration for someone because of their abilities, qualities or achievements. Respect is earned. You are respected by others for what you have achieved, experienced and how you have handled yourself as you have achieved accomplishments.

The problem is we use respect in two distinctively different ways: Recognizing a power or status difference between people or recognizing the value of a person. When it comes to children, we commonly frame being respectful as being polite, obedient and following the rules. In this context, questioning the rules or challenging the person enforcing the rules is often perceived as defiant, rude, disrespectful and subject to punishment.

The questions then become: Should you respect someone in a position of authority who abuses power? Should you respect someone who doesn’t treat others with dignity? Even if they’re older than you? Even if they have more seniority than you? Even if they have more experience than you? If dignity is a given that can’t be taken away, what does it look like to treat someone you don’t respect with dignity?

That’s the contradiction that’s so hard to put into words. It’s one of the reasons why young people are so often skeptical about what we teach and model about respect. In their minds, they may question “respecting” someone who treats others badly and then demands respect themselves?

They see people using their position as a way to get away with treating people badly.

If we use dignity as our anchor and ground our work in the belief that every person has value, then we can separate people’s abusive actions from their essential humanity. For example, there may be a teacher at your school who belittles students or embarrasses them in front of others. Your students shouldn’t respect the teacher’s behavior but they should absolutely treat that teacher with dignity. It may look like the same thing—treating the person with respect versus treating that person with dignity but in young people’s minds, it is an important distinction. Respect acknowledges the behavior while dignity teaches the importance of civility and humanity.

The same concept can be applied to a peer situation. Students get rightfully frustrated when other kids are mean. They want revenge. They want the right to hate this other kid. If we say, “Yes, you have the right to be incredibly angry. I’m not taking those feelings away from you. But here’s how I want you to think about it: You don’t have to be friends. You don’t have to respect them. You don’t have to like them or what they’re doing. But you do have to treat them with dignity.”

Recent Posts

Dignity vs Respect

Acting Out: How a Theatre Techniques Class Teaches Social Skills

How to Punish (and How Not to Punish) a Teenage Boy

This post appeared on CrisisGo– who provides tools for schools to increase safety awareness, improve rapid response, connect parents and school staff, and improve procedures with comprehensive data.

The post Dignity vs Respect appeared first on Cultures of Dignity.

April 17, 2018

Acting Out: How a Theatre Techniques Class Teaches Social Skills

Ava Rigelhaupt is a founding member with the neurodiverse theatre company, Spectrum Theatre Ensemble of Providence. She lives in Rhode Island and is a rising junior at Sarah Lawrence College. She took a gap year between sophomore and junior year to work with #STEProvidence. In her free time, Ava enjoys writing, horseback riding, and making soups. Feel free to check out Ava’s other blog on Cultures of Dignity!

Enjoy Ava’s piece on how theatre can teach social skills by honoring everyone’s worth and experience.

Acting Out: How a Theatre Techniques Class Teaches Social Skills

By Ava Rigelhaupt

The revolution begins in the classroom. This revolution is taking place at The Autism Project of Rhode Island in a social skills class called “Curtain Call.” Peer to peer interaction is often one of the biggest challenges for people on the spectrum. Research shows that acting and theatre are some of the best ways to teach and learn social skills. After all, acting is scripted interaction where mistakes and social faux pas are accepted and encouraged.

The mission of Spectrum Theatre Ensemble of Providence (STE) is to “evolve the tools, practitioners, and awareness necessary to empower those who struggle to make themselves heard.” STE is challenging society’s idea of what it means to have a “disability.” The prevailing belief in society is that people with disabilities cannot work, (in the arts or otherwise), or can only work at McDonald’s. STE is creating the next generation of artists with disabilities and giving them the tools to carve out their own space in society.

When Clay B. Martin, the founder and artistic director of STE, first asked me and two other STE interns to assistant teach at the Autism Project of Rhode Island, I was incredulous. “You want me to teach other young developing humans?” I thought, “I’m not even done with my undergrad. What do I have to offer?” I’ve never taught before, save for the horseback riding summer camps where kids labeled horse anatomy. Summer camp is a lot different than a classroom, and none of those kids, (known), were on the autism spectrum. Taking a gap year from college as well as working with a new neurodiverse theatre company was a ton of firsts; here I am again with firsts. It was my first time formally teaching, and first time interacting with younger kids on the autism spectrum. But, like jumping in with STE, I’m so glad I did.

I get to see first-hand what it looks like to teach the next generation.

I get to see first-hand what it looks like to teach the next generation. My role is to observe the classroom overall and take notes on what improved, how the exercises could be changed, or record amazing student one-liners said during scene improv that we want to keep in our final project. I enjoy seeing the students grow, becoming more confident with themselves and their onstage decisions each week.

Emma¹ is a great example of this growth. She started off as mostly nonverbal², struggling to express herself and inner life. She was tentative and didn’t wish to participate in the class. One time, we heard Emma mutter something to one of the aids. When asked, the aid told us, “Emma doesn’t like Disney.” Since a lot of the class did like Disney, we were using those characters and motifs as starting points for our improv games and icebreakers. When we learned Emma didn’t like Disney, we asked the class if it was alright to take a break from those stories and try something new. Suddenly, Emma was willing to join.

Why didn’t Emma just speak out in the first place? For many people on the autism spectrum, verbalizing and expressing their inner world so others can understand is a challenge. By the time we find the words, the situation has changed. Even if it’s a couple extra minutes, the impatient and oblivious world moves on; we have not. Our minds work at different speeds and wavelengths than neurotypical minds. I compensate for this by staying quiet. I try to make sure what I’m about to say is really relevant to the conversation, which can be a different conversation than the one my mind was processing. (Yes, it’s taxing). Too often, school-aged girls – like me – quiet and following directions – are overlooked. For one teacher with 25 students, the quiet one is the least concern. The teacher thinks there are no problems with Miss Quiet. But, just because there are no tantrums or outbursts does not mean there are no problems, no misunderstandings, no undiagnosed neuro-differences.

For many people on the autism spectrum, verbalizing and expressing their inner world so others can understand is a challenge. By the time we find the words, the situation has changed.

Fewer girls are diagnosed with autism than boys. Boys often are more disruptive in their Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) presentation. I know for one teacher and 25 students and a full schedule to get through, noticing and analyzing the quiet student can be an impossible feat. Luckily, this is not our class. Our class has four students and three teachers, along with aids/teachers from The Autism Project. This allows enough personal attention to make sure all the students are on the same page. If someone is having a hard day or not grasping an exercise, we can change direction, maybe returning to a familiar activity. The most rewarding is when we change the class because of students’ positive steps forward. Such as Emma speaking on a regular basis. Emma is now playing pranks on the teachers, and speaking nonstop. Through our inclusive theatre work, she is finding more opportunities to communicate. Wanting to gently challenge Emma, we gave her a leading role in our final project, we made her a nonverbal heroine who expresses herself through gestures. As we progressed, Emma gained confidence. We realized her role needed lines!

To an outsider, our class progress appears slow and hard to quantify. Like most learning experiences, some days we take 5 steps forward, yet other days we take 20 steps back. Each week, I enjoy seeing the smiles and eagerness of the students who, like us, are just as surprised at their own growth. While our classwork is a mere hour of the kids’ lives, during that hour they are told they are worthy, valued, and listened to just like the neurotypicals of our society. People with disabilities deserve the same respect, resources, and rights. Because what is normal? What is neurotypical? Answer those questions. Perhaps society needs to go back to the drawing board, like Spectrum Theatre Ensemble does every week at the Autism Project.

While our classwork is a mere hour of the kids’ lives, during that hour they are told they are worthy, valued, and listened to just like the neurotypicals of our society.People with disabilities deserve the same respect, resources, and rights. Because what is normal? What is neurotypical?

¹ Name is changed for privacy.

² Some people who are nonverbal physically cannot speak. The exact reason and brain connection etc. has not been found. Some people who are nonverbal have the physical function of speech, but verbal communication and expression is difficult. Please remember that not speaking doesn’t always equal not comprehending! (Assessing the Minimally Verbal School-Aged Child with Autism Spectrum Disorder)

If you have questions for Ava, feel free to email curious@culturesofdignity.com

Image from Unsplash

Recent Posts

Acting Out: How a Theatre Techniques Class Teaches Social Skills

How to Punish (and How Not to Punish) a Teenage Boy

‘Lovesick’ Is A Sick Excuse For A Young Woman’s Death