Michael J. Roueche's Blog, page 2

June 3, 2015

Confederados: Brazilian Neighbors I Never Knew

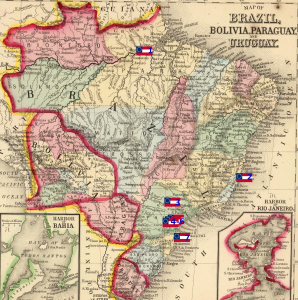

The Protestant chapel at Campo (Field) Cemetery (Cemitério do Campo) where many of Os Confederados are buried. The cemetery is now in Santa Bárbara d’Oeste (West Santa Barbara), previously Santa Bárbara. It was originally a field donated as a cemetery by one of Os Confederados. Santa Barbara is next to Americana.

About 15 years ago, I met a middle-aged woman in Virginia who spoke English with an accent I didn’t recognize. When she heard I’d lived briefly in Brazil many years earlier, she enthusiastically identified herself as a native of Vila Americana, a town in Brazil. I could tell the revelation was significant to her. But not to me.

I’d never heard of the Brazilian town, even though I lived briefly as a conspicuous American in several locations in the State of São Paulo where Americana is located. I hid ignorance about her hometown as I was sure she would be disappointed. But from our brief conversation I gleaned Americana had been the chosen home of Confederates fleeing post-Civil War America, including her ancestors.

Since meeting her, I’ve read a bit about Os Confederados (“The Confederates” who migrated to Brazil), and recent articles in Smithsonian Magazine and The New York Times reminded me of my experience.

Most modern articles emphasize the linguistic peculiarity of a people speaking English with an accent reminiscent of the deep South in 1865. Perhaps a few descendants of Os Confederados do speak English with something like a Southern accent, although I am instantly suspicious of such claims, doubting the 150-year survival of any speech pattern dominated by another language and culture. The accent was already suspect by 1979 when an American writer visited Confederado descendants in Brazil, noting in a fascinating article about his encounter:

The man spoke an American English that, while wholly fluent, sounded nothing like I had ever heard before. There was the cadence, a slow molasses drawl, but there was more. The words sounded like they came from deep within the bowels of Georgia, maybe just north of Macon, where the gnat line begins. But that wasn’t it either. The man had a Portuguese accent, and his inflection and the words he used, how he strung them together, it sounded all wrong. His speech was wobbly and splintered, run together, so some of the words didn’t make any sense.1

There remains a “romance” (sometimes a romantic sadness) in writings and videos from outsiders about Os Confederados. But it is only from a safe 5,000-mile distance untouched by the cultural revolutions of the post-Civil-War US that anyone can speak without inhibition (almost with pride and flippancy) about being the “only…unreconstructed Confederates on the earth because…we never pledged allegiance to the damn Yankee flag.”2

Interestingly, in spite of being unreconstructed, descendants of Os Confederados maintain sentimental attachment to the US as well as the Antebellum South, just as former Confederates in the States created a post-war Southern culture that featured a strong allegiance to the United States. In 1915, one Vila Americana-area resident Cicero Jones wrote of Os Confederados, “All are more or less content and would fight for the Stars and Stripes as we would for the Stars and Bars.”3

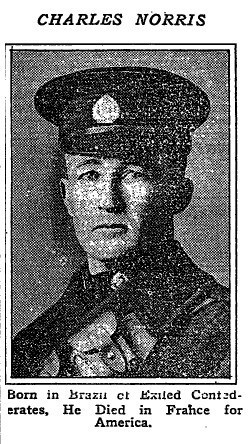

Charles Norris as his picture appeared in the New York Times, September 2, 1928. The accompanying article noted he died fighting for the US Army in “the World War.”

Since the Stars and Bars saw no more action, that part of his statement remains untested, but within three years of Jones’ statement, the Confederados had lost one family member, Charles Norris, grandson of the community’s founder who had married a “local” woman and had several daughters. Although he’d never been to the United States, he “went” home to serve in the American Army during World War One and was killed in France.4

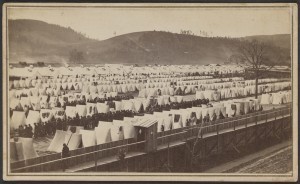

Well documented is the small, annual Festa dos Confederados (Confederate Festival) where descendants of the most successful Confederado colony, Americana, sometimes dubbed the lost colony of the Confederacy, celebrate their heritage and raise funds for maintenance of the cemetery founded by the colonists. The cemetery was originally established because the immigrants were mostly protestant in a Catholic country that wouldn’t allow “heretics” in Catholic cemeteries.

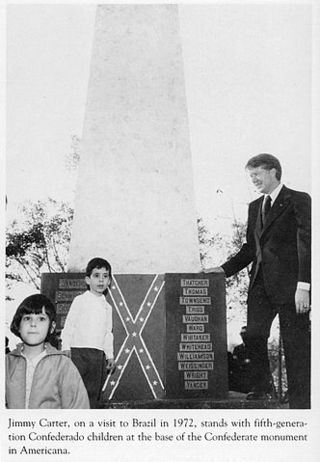

Thoughtful reflection on the experience of Os Confederados leaves one with mixed feelings, but they’re the sentiment of an outsider. You can’t help sharing Governor, later President, Jimmy Carter’s thoughts after a 1972 visit he and his wife, Rossalyn—whose great uncle W.S. Wise was one of Os Confederados buried in the cemetery of Os Confederados—made to Americana, as reported in the Atlanta Constitution:

Then Governor Jimmy Carter visited Campo Cemetery in 1972.

My most significant feeling was one of great sadness they had foregone for all those generations the enjoyment of being a part of this nation they still revere so deeply. The futility of it all was apparent. None of them looked upon their ancestors as mistaken. They didn’t seem to feel any self-pity.5

In the end, I suspect, Os Confederados, in spite of their affection and admiration for the US, the Confederacy and their ancestry, will continue to be slowly woven into the rich Brazilian tapestry till few will remember from what yarn a strand of them comes.

Even in 1928, the signs of coming acculturation were pressing down on Os Confederados. Josephine Crowder wrote in the New York Times of her visit to a Mrs. Jones of Americana, granddaughter of Confederate Colonel W. H. Norris from Alabama, the first Confederado settler in the area. He had migrated to Brazil with his son, Robert, Mrs. Jones’s father, sending for the family after they got settled. Crowder noted, “struggle as hard as she can, Mrs. Jones cannot keep her children Americans. Sooner or later Brazil will get most of them.”4

William Clark Griggs in his book about Os Confederados, published nearly 30 years ago, wrote:

Fourth generation Brazilian-Americans in most cases no longer speak English and thus are losing a significant part of their heritage. Letters and documents treasured by their families for over a century can no longer be read by some and consequently have lost much of their meaning to this newest group of descendants of Confederates. …The new generation of Brazilian-Americans are becoming Brazilian in the truest sense of the word, but it took over 120 years for the change to occur.3

A Closer Look at Os Confederados

What attracted Confederados to Brazil?

Fear of Northern oppression and a bleak economic future encouraged Confederados to flee the US.

Os Confederados were swept to Brazil by a perfect storm consisting of a felt need of the Southerners to escape difficult post-war circumstances in the US, agents and promoters who went to Brazil and published encouraging reports, and a Brazilian government urgently needing increased population and skilled laborers.

Escape

One young woman wrote, “’there is complete revolution in public feeling. No more talk about help from France, or England, but all about emigration to Mexico or Brazil.”3

George Washington Keyes, one of Os Confederados, wrote to a friend in 1869, “I left the United States because of the anarchy I expected to prevail, poverty that was already at our doors, and the demoralization which I thought and still believe will cover the land.”5

Confederado Robert Morris commented 50 years after leaving the US, “ You folks made our lives so impossible in the United States that we had to leave.”5

In 1995, the Seattle Times reported the Judith McKnight Jones, who was 68 at the time, great-granddaughter of one of the original Confederados as saying, “They came here because they felt that their ‘country’ had been invaded and their land confiscated. To them, there was nothing left there. So, they came here to try to re-create what they had before the war.”6

Promoters and Agents

Interest in Brazil was heightened by travel guides and books about the country, some predating the war. Confederates in various states set up emigration societies to explore moving to Brazil, and some agents published pamphlets and information about Brazil, further inflaming interest in the massive country. Some offers and agents were fraudulent, and some colonists would live to suffer under the deceit. When the first emigrants entered Brazil, they also began writing home about the possibilities of the new country, and some of these letters made their way into newspapers.7

A Welcoming Nation

Many of the arriving emigrants stopped in Rio de Janeiro, capital of Brazil, where the Emperor Don Pedro II’s imperial government housed them in a luxurious government hotel.

Both the government and the culture of Brazil attracted the colonists. The country remained neutral during the war, but sought ways to help the North American Rebellion. Brazil’s culture was like that of the South in some ways, including being “ruled” by a rural aristocracy.5

Brazil also wanted to promote emigration. In 1850, slave importation ended and the government wanted to attract workers to make up for labor loss. The government enacted the Immigration Law of September 27, 1860 which called for free colonies which could govern themselves, and subsidies for roads, schools, churches and land. It provided immigrants with temporary shelter and moved colonies located far from regular transportation to more accessible sites.7

Emperor Don Pedro II, “the magnanimous,” a long-standing opponent of slavery, encouraged and welcomed the fleeing Confederados.

Emperor Dom Pedro II personally extended invitations to the Rebels and met with some Confederado agents. When they first arrived, emigrants were given food and lodging in a luxurious government hotel. The Emperor at least once visited emigrants in the hotel. After their brief, comfortable stay, the pioneering Confederados were sent to their chosen place of residence with the government covering cost of transportation. The government also subsidized, with loans, passage for some emigrants to come to Brazil.5

However the government was in the middle of a war and never kept all its commitments, eventually leaving some Confederados in poverty with little possibility of escape.

How many Southerners fled to Brazil after the War?

Estimates cover a wide range from a few thousand to 20,000. Eugene Harter, descendant of Os Confederados, who with his parents and siblings returned to the US in 1935, claims 20,000 based on a study of available sources.5 But with incomplete records and the fact that some came individually, the best answer is nobody really knows. Likewise, it’s impossible to know how many returned to the US or stayed in Brazil. Some who remained in Brazil assimilated into local populations.

What type of men and women went?

The failed Mexican immigration movement included more high-ranking Confederate officers, but the Brazilian emigrants were stalwart Confederates, as shown by brief biographies of various men on the website of Fraternidade Descendencia Americana, an association of Os Confederados descendants,8 including:

Robert Cicero Norris (r) served in the Confederate Army while his son Charles (l), a Brazilian native, would die fighting for the US in World War 1. (ancestry.com)

Robert Cicero Norris: Private, Company F, 15th Alabama Infantry & 1st Lieutenant company A, 60th Alabama Infantry. He was alive in 1913, age 75. He was born on March 7, 1837, in Perry County, Alabama, but was a resident of Dallas County, Alabama. He was the son of William H. Norris, and was educated at Fulton Academy & Mobile Medical College. He enlisted on January 28, 1861, under Capt. Theodore O’Hara to take Pensacola Navy Yard. On July 3, 1861, he enlisted in Co. F, 15th Alabama Infantry, in Stonewall Jackson’s Brigade. In 1862, he was appointed Sergeant Major, and in 1864, was appointed 1st Lieutenant of Co. A, 60th Alabama Infantry. He was wounded 4 times and fought at Malvern Hill, Cold Harbor, Cedar Run, 2nd Manassas, Sharpsburg, Gettysburg, Chickamauga, Wilderness, Petersburg, etc. He was captured at Hatcher’s Run & held at Ft. Delaware until June 17, 1865. He went to Brazil in 1865, but returned in 1890 to finish his medical degree. He returned to Vila Americana, Brazil and practiced medicine. He was a master mason. He died on May 14, 1913 in Brazil.

Ezekiel B. Pyles: Private, Company A, 11th Kentucky Cavalry & Company D, Dortch’s 2nd Battalion Kentucky Cavalry. He originally joined Company A, 11th Kentucky Cavalry in September 1862, and accompanied Gen. John Hunt Morgan on his great Ohio Raid. He escaped by swimming the Ohio River at Buffington Island, and joined other Morgan’s Men in Co. D of Dortch’s 2nd Battalion Kentucky Cavalry in August 1863, at Knoxville, Tennessee. He fought in the Tennessee & Georgia and at the Battle of Saltville, Virginia, on October 2, 1864. He was assigned to the brigade of Gen. Basil W. Duke & was captured at Kingsport, Tennessee, on December 13, 1864. He was taken to Camp Chase, Ohio, where he was imprisoned until February 17, 1865, when he was transferred to Point Lookout, Maryland, for exchange. After his exchange, he was admitted to a Confederate military hospital at Richmond, VA, on February 26,1865. He was furloughed from hospital for 30 days on March 6,1865, and returned to southwest Virginia where he re-joined his command. When the rest of his command disbanded on April 12,1865, he refused to surrender and made his way to Greensboro, North Carolina, where he became part of the final escort for Confederate President Jefferson Davis. After being released from service by President Davis, he surrendered at Washington, Georgia, May 10, 1865. He went to Brazil and was still alive in 1913, age 66.

Did legal slavery in Brazil motivate Os Confederados to choose that country?

Slaves in coffee yard of farm in São Paulo, 1882–six years before slavery ended. (NPR: http://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2013/11/12/244563532/photos-reveal-harsh-detail-of-brazils-history-with-slavery)

It was an attraction for some Confederados, and some did buy slaves when they arrived. (Slaves cost about half the price in Brazil as in the US.) Others—maybe most—didn’t have the means to buy slaves, if they had been so inclined. Slavery in the massive South American country by the time the Southerners arrived was sloping toward 1888 peaceful extinction.5

Slavery in Brazil was dramatically different from that of the US South. Only the South’s largest slaveholders rivaled holdings of the hundred slaves of the average Brazilian slaveholder, perhaps making the South American form less “paternalistic” and perhaps, if possible, less personal.9

Some slaveholders in the US, deceiving themselves, perceived or claimed slaves as an “extension” of their family, leading to accounts of masters and mistresses being surprised and disgusted by the “disloyalty” of slaves at emancipation when freed slaves left their former owners. With such large numbers of slaves, Brazilian holders were less likely to take that view. Slavery in Brazil also may have been harsher, especially during the sugar cane harvest when slaves worked 18 hours a day in the fields.9

Race relations were different as well in the Latin country. Brazilian sociologist Josè Arturo Rios, writing of the challenges of the settlers, noted:

They imagined they would find in Brazil, a slave-holding country, the same segregation between whites and blacks. …For a long time…the social rise of Negroes and mulattoes had been going on, and the Southerners found themselves, to their stupefaction, in a society in which the color criterion was not the dominant one for social classification. With consternation they saw mulattoes and Negroes in the bosom of society, occupying important positions, and, through that fact, ceasing to be regarded as Negroes.5

What was the position of US Government, Southern leaders and newspapers?

The immigration was discouraged by most in the States.

Jefferson Davis initially petitioned the government to allow his family to immigrate, but after his release from government custody wrote, “Because the mass of our people could not go, the few who were able to do so were most needed to sustain others in the hour of a common adversity.”5

Robert E. Lee was one of those who encouraged former Confederates to stay in the US. (Library of Congress)

Robert E. Lee offered in a letter, “They should remain, if possible, in the country; promote harmony and good feeling, qualify themselves to vote and elect to the State and general legislatures wise and patriotic men, who will devote their abilities to the interest of the country and healing all dissensions. I have recommended this course since the cessation of hostilities, and have endeavored to practice it myself.”5

Union authorities also discouraged flight from the country.

Media in both regions discouraged it. The Montgomery Advertiser, on August 10, 1867, published:

The American citizens live about in huts, uncared for—there is much general dissatisfaction among the emigrants and the whole Brazil representation is a humbug and a farce. The American Consul is in receipt of numerous and constant applications from helpless American citizens to assist them in getting back to their true, rightful country . . . . Dissipate the idea that Alabama is not still a great country—cease dreaming over the unhappy past—say nothing that will assist to keep up political troubles, stay at home, but work, work, work and Alabama will yet be, what she ought to be and can be, a great and glorious country.5

The Galveston Daily News observed on January 18, 1867:

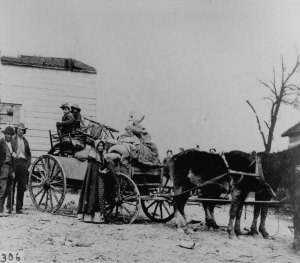

We noticed a number persons on the street yesterday destined for Brazil. The party consisted of women and children, convoyed by several men with guns on their shoulders. All were evidently from the country, and as we gazed upon them, could not help experiencing a feeling of sadness, partly from thinking of the causes that induced them to leave the land of their nativity, and partly because they were about entering upon a life new to them; and we fear, little think of the dangers, trials, and hardships incident to being a stranger in a strange land.3

The New York Times crowed in 1870 when 120 of Os Confederados returned to the States. The paper hoped returning emigrants’ disappointing experiences would discourage others thinking of escape. It opened an article headed “Another Brazilian Bubble Burst” with this “neutral” observation:

Everybody recalls the fever for Central American and South American colonization which seized some of our people in 1865. It raged chiefly in the South, where, at the close of the war, some heartless or deluded ultra-Confederates persuaded many of their country men to quit their native shores forever, rather than to return to the ‘hated Union.’10

What became of Os Confederados?

Some Confederados slowly mixed with local Brazilians assimilating into country and culture. Others migrated to the more successful colony that would eventually be called Americana. Some returned to the United States because of financial difficulties; disillusionment; lack of local transportation; homesickness related to distance from family and friends; language, religious and cultural issues and differences; inability to vote; and low pay for skilled workers.3

Additionally, the Brazilian government failed to live up to many of its commitments to the Confederados, and within a few short years, many were destitute and desperate to return to the States.

Confederados emigration continued into the early 1900s.8

Ironically, among emigrants who remained in Brazil were former slaves who migrated with white Southerners. A man named Rainey (I don’t know if that’s his first or last name.) settled in Rio de Janeiro and created a successful ferryboat business. Stephen Watson migrated with his former master Judge James Harrison Dyer to Frank McMullan’s New Texas colony, trusting his former master more than the economic uncertainties of the post-war South. Dyer operated a variety of businesses. Watson quickly learned Portuguese, enjoyed living in Brazil and helped Dyer build a profitable sawmill. A financial setback and homesickness sent Dyer back to the states, but he transferred ownership of his remaining property–the sawmill and land–to Watson who proved more than up to the task. He “became very wealthy, married a Brazilian lady, and had a large family. He was highly admired in the region.”5

Did the colonists impact Brazil?

The moldboard plow was a significant Confederado contribution to Brazilian agriculture.

There were probably too few colonists and scattered too broadly to change the course of the young nation. However, Confederados did improve Brazilian agriculture. They introduced, produced and repaired the moldboard plow in an agriculturally focused country still using the hoe, leading one settler to claim of that introduction, “the leaven sown…has transformed a country whose area is larger than the U.S. By transformation, I mean agriculture, and that means all.”3

“Once a Rebel, Twice a Rebel”:

These words mark a headstone in the Confederados’ cemetery, highlighting one more irony in the history of the colonists. In 1932, São Paulo, the most wealthy Brazilian State, led other states in a rebellion against the provisional federal government set up following a government overthrow. The coup d’état had defeated a constitutionally elected government and set new limits on states rights. Among the rebels thus fighting for states rights were residents of Americana, descendants of the North American Rebels. Brazilian dictator and head of the provisional government Getulio Vargas put down the rebellion, offering quick amnesty to those who had fought against his government.5

What were their main settlements?

1) Santar è m

Lansford Hastings led Confederado settlers to the unforgiving environment of the Amazon. George Barnsley, an emigrant who originally joined the New Texas settlement, claimed Hastings’ effort “attracted much attention and a number of emigrants settled near him, but either through the climate, or rains, or insects, or more probably laziness, his colony came to nothing.” The reality was that while unsuccessful settlers moved on, some remained. There were 92 colonists on the land in 1888.3 In 1940, original settler David Riker, could report, “I’m glad I stayed on. God has been good to me. My sons are good sons, my daughters are good daughters. My wife is good and true. We lack for nothing we ought to have. How many can say the same?”5

A 1983 tour guide-book of South America noted of Santarèm:

This city…was settled in 1865, by residents of South Carolina and Tennessee who fled the Confederacy where slavery was abolished. …It now serves as a supply center for miners, gold prospectors, rubber tappers, Brazil-nut gatherers, and the jute and lumber industries. Several bars display the Confederate flag, and you still occasionally meet the settlers’ descendants, who mixed with the multiriacial Brazilians and have names like Jose Carlos Calhoun.5

2) Rio Doce

Founded by Colonel Charles Gunter, the Confederado settlement promised early success, but malaria, serious drought and lack of government-promised steamship service weakened the community. Some professionals in the colony migrated to Rio de Janeiro. Others moved to other settlements or assimilated into surrounding Brazilian life. Gunter died at the settlement in 1873.5

3) Villa/Vila Americana (settlement near the Brazilian town of Campinas)

The most successful and well-known of the settlements was established with colonists living close together. The community that would become Americana attracted emigrants from other struggling Confederado colonies. It’s home to the annual Festa dos Confederados and is featured, along with its residents and festa, in most contemporary media about Os Confederados. It was founded by Colonel William H. Norris who purchased the five-hundred acre Machadinho Estate and three slaves.5

An American historian has written of the Confederado colony:

In many ways the emigrants comprising the group in and near Villa Americana, as the settlement came to be called, were the happiest and most successful group in Brazil. This was perhaps due to the homogeneity of the group and to the fine and unselfish leadership of the Norrises, father and son, who were men of sufficient means to help the settlers overcome the first financial difficulties.7

4) Juqui à

It was an enterprise of Reverend Ballard Dunn who scouted Brazil for emigration and returned to the US to write a book about the country, hoping to recruit colonists. The 350 Confederado recruits traveled to Brazil subsidized by loans from the South American country. He called his colony Lizzieland for his deceased wife. Barnsley described the site, as “extremely picturesque, but with the slight defect of being without good lands and in the rainy season was half under water.” Dunn mortgaged the land for $4,000 and three months after settling his colonists on the vast tract of Brazilian land, the Reverend left Lizzieland, never to return. Floods shortly afterwards destroyed improvements and many of the settlers melted into the Brazilian cultural landscape or slipped to other colonies.3,5

5) New Texas

Texans Frank McMullan and William Bowen organized a colony of 152 Confederados. McMullan died shortly after arriving in Brazil, and leadership of the colony fell to Bowen. But Confederado Judge James H. Dyer fought for control of the settlement. The conflict, isolation, homesickness, shortage of food and money, and inability to build roads to get their crops to market soured most colonists on the chosen site and by 1870 all had returned to the US or resettled in other areas, especially the thriving settlement which would eventually be named Americana. Dyer stayed, building several successful sawmills and operating a steamboat, all the while searching for a hidden treasure of gold. When a storm took the steamboat, Dyer gave up, sold one sawmill and gave the other and his remaining property to his former slave, Steve Watson (Vassão), and returned to the States.3,5

6 Xiririca

Dr. James McFadden Gaston, a surgeon from South Carolina scouted Brazil for settlement and wrote the 1866 book “Hunting a Home in Brazil.” He headed a 100-person Confederado settlement, but most moved over time to other areas of Brazil till the settlement essentially evaporated into other settlements or into Brazilian culture. Gaston moved several times himself, eventually ending up with a medical practice in the Brazilian town of Campinas, State of São Paulo, close to Americana.3

7) Paranagu à

Colonel M.S. McSwain and Horace Land headed a colony to the Brazilian state of Paranà just to the South of São Paulo. Some of the colonists assimilated into ethnic groups around Paranaguà, especially German communities, while some returned to the US.3

Sources:

1 Bloom, Steven G. “Brazil’s Secret History of Southern Hospitality.” Brazil’s Secret History of Southern Hospitality. Narrative.ly. Web. 19 May 2015. .

2 23mbtx23. “Confederates in Brazil.” YouTube. YouTube, 22 Apr. 2011. Web. 15 May 2015. < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oBWR5oY8gG8 >.

3 Griggs, William Clark. The Elusive Eden: Frank McMullan’s Confederate Colony in Brazil. Austin: U of Texas, 1987. Print.

4 Crowder, Josephine. “A Stanch American Who Has No Country.” ProQuest Historical Newspapers [ProQuest]. The New York Times, 2 Sept. 1928. Web. 20 May 2015.

5 Harter, Eugene C. The Lost Colony of the Confederacy. College Station, TX: Texas A & M UP, 2000. Print.

6 Harris, Ron. “Confederates In Brazil: They Fled American South.” Seattle Times 4 May 1995. Seattle Times. Los Angeles Times. Web. 01 June 2015. <http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19950504&slug=2119240>.

7 Weaver, Blanche Henry Clark. “Confederate Emigration to Brazil.” The Journal of Southern History 27.1 (1961): 33-53. JSTOR. Web. 01 June 2015. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/2204592?ref=no-x-route:ba95436c52ed94d39333a6dd86966133>.

8 “SCV Camp #1653 “Os Confederados” – Brazil.” SCV Camp #1653 “Os Confederados” – Brazil. Web. 01 June 2015. <http://www.confederados.com.br/>.

9 Genovese, Eugene Dominick. Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. New York, NY: Vintage, 1976. Print.

10 “Another Brazilian Bubble Burst.” ProQuest Historical Newspapers [ProQuest]. The New York Times, 25 February 1870. Web. 20 May 2015.

Additional Os Confederados Resources:

Americana (Brazil) Oral History Project Collection. Emory University <http://findingaids.library.emory.edu/documents/americana740/>

“Ex-Confederates in Brazil.” ProQuest Historical Newspapers [ProQuest}. The New York Times, 22 April 1928. Web. 20 May 2015.

Facebook Page: <https://www.facebook.com/pages/Os-Confederados-Brasil/263483417358>

Hawkins, Gary. “The Lost Confederados: Why thousands of Southerners fled to Brazil after the Civil War, why they stayed, and why their descendants still remember.” Garden and Gun Magazine September/October 2008. Web 29 May 2015. <http://gardenandgun.com/article/lost-confederados>.

Hendrick, Bill. “The Confederados: Descendants of Rebel Soldiers, Young Brazilians Visit the South to get in Touch with their Past.” The Atlanta Constitution, 10 August 1998. Wesclark.com. Web. 19 May 2015. <http://wesclark.com/jw/brazil.html>

Hoge, Warren. “Confederates’ Descendants Keep Tradition in Brazil: Insisted on English Textile Center of 120,000.” ProQuest Historical Newspapers [ProQuest]. The New York Times, 19 August 1979. Web. 20 May 2015.

Luft, Kerry. “In Brazil, A Touch of Johnny Reb.” The Chicago Tribune, 30 April 1995. Web. 29 May 2015. <http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1995-04-30/news/9504300190_1_brazil-alabama-state-senator-sao-paulo>.

Malanowski, Jamie. “The Civil War: The Underappreciated and Forgotten Sites of the Civil War.” Smithsonian Magazine Apr. 2015. Web. 15 May 2015. <http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/underappreciated-forgotten-sites-civil-war-180954579/>.

Soodalter, Ron. “DisUnion: Confederates in the Jungle.” The New York Times 8 May 2015. Web. 15 May 2015. <http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/05/08/confederates-in-the-jungle/>

Tigay, Alan M. “The Deepest South: Five Thousand Miles below Mason-Dixon Line, a Brazilian Community Celebrates Its Ties to Antebellum America.” American Heritage Magazine Apr. 1998. Web. 29 May 2015. <http://www.americanheritage.com/content/deepest-south>.

The post Confederados: Brazilian Neighbors I Never Knew appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

May 25, 2015

Memorial Day: Established to Remember the Civil War Dead

Arlington House (the Custis-Lee Mansion) overlooking graves at Arlington National Cemetery was draped in black for the first Decoration Day in 1868.

Happy Memorial Day! (Is one to be happy on Memorial Day? Or should we be thoughtful and grateful?)

Memorial Day was originally established as Decoration Day just after the Civil War to remember soldiers (Union and Confederate) who had died during the conflict. Later it was extended to all who died in military service. According to the government’s Veteran’s Department:

Three years after the Civil War ended, on May 5, 1868, the head of an organization of Union veterans — the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) — established Decoration Day as a time for the nation to decorate the graves of the war dead with flowers. Maj. Gen. John A. Logan declared that Decoration Day should be observed on May 30. It is believed that date was chosen because flowers would be in bloom all over the country.

The first large observance was held that year at Arlington National Cemetery, across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C.

The ceremonies centered around the mourning-draped veranda of the Arlington mansion, once the home of Gen. Robert E. Lee. Various Washington officials, including Gen. and Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant, presided over the ceremonies. After speeches, children from the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Orphan Home and members of the GAR made their way through the cemetery, strewing flowers on both Union and Confederate graves, reciting prayers and singing hymns.

Lincoln spoke for all future Memorial days when he praised those who had given “the last full measure of devotion” during his “few brief, but most appropriate, words” at Gettysburg.

On this Memorial Day, thanks to all who have served our nation and especially today to those who gave “the last full measure of devotion.” Lincoln, of course, at Gettysburg, when that battlefield lay quiet, captured it for all Memorial days to come:

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

The post Memorial Day: Established to Remember the Civil War Dead appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

May 5, 2015

Living History: Getting Young People Involved

Living History Reenactor Charlie Carter portrays Betsy in photo used on final Beyond the Wood cover.

Several years ago, a short time before publishing “Beyond the Wood,” we happened to visit family in a small college community in Michigan. As we drove into town, we saw a sign promoting a Civil War living history reenactment the next day.

Final Cover, with Charlie’s image, as designed by Nick Zelinger.

We convinced the family we were visiting to come with us to watch the reenactors of the 10th Michigan.

While at the living history event, my wife noticed a young woman she thought would look great on the cover of the book. (I didn’t even know we were worrying about a cover.) My wife introduced herself to reenactor Charlie Carter, and Charlie graciously agreed to pose for a few photographs. One of those photos now graces the book’s cover.

We reached out to Charlie recently to see how she was doing and ask a few questions about her living history experiences. To illustrate my belief that living history and reenactments interest young and old about the past, I’m posting my interview with her:

Charlie, how did you get into living history?

My family discovered reenacting when my brother was in Boy Scouts in about 2006-2007. His den leader, Susan, was a reenactor, and for one of the boys’ badges, they had to pick up the empty cartridge packets after each reenacting battle.

My mother has always been huge into history and the Civil War, so we would all go with my brother and make it a family outing. We went every year, and in 2011 she finally convinced my dad to dress up. Since then we have attended many more events and have a wonderful portrayal.

I started dressing up in 2008. I loved the dresses. I thought they were so beautiful and elegant. Susan, my brother’s den leader, was at that 2008 reenactment and was kind enough to dress me, and I got to walk around with her for the day.

When we met you, you were with the Michigan 10 th . Is that the unit you always portray?

Yes, we were with the 10th Michigan Infantry, but we’re currently with Michigan Living History Education Association (MLHEA) based out of Bay City, Michigan. We typically portray the unit as either Confederate or Union, whichever the reenactment needs. However, we probably portray MLHEA as Confederates 75 percent of the time.

(Note: The MLHEA is unusual in the variety of living history it portrays. According to its Facebook page it portrays “the Fort Saginaw Infantry 1822, Civil War 16th Michigan, 114th Pennsylvania [Zouave], the 27th Virginia Rockbridge Rifles, 3rd Division (WW1) and 3rd Division (WW2), Air Force and Infantry of Vietnam in the Greater Michigan Area.” It is “a timeline organization for Michigan history spanning from 1822 to the 1960s.”)

You recently finished making your first Civil-War-Era dress to use in your living history portrayal. I understand the dress was named a 4-H fair reserve grand champion. Congratulations! How long does it take and what goes into making a civil-war era dress?

Charlie models award-winning Civil War dress of her own creation.

It depends on the style, and how advanced your pattern reading and sewing skills are. The dress I made took about a month, one day a week, for 2-3 hours a sitting. I had a teacher from a local school guide me, and we had to fit it into her crazy schedule.

It was a fancier dress because of the pagoda sleeves, and technically I should have sheer or light cotton under to go underneath, but I haven’t gotten around to making them yet.

Close-up detail of fabric and lace of Charlie’s dress.

It is more an afternoon-evening dress, and could be dressed up even more for a ball gown. It’s actually pretty easy to move around in. Once you learn how to position the skirt so you can sit, you’re all set. The hoops move with you and its surroundings. If you squeeze between the table and the tent pole, it folds and comes right behind you! It is extremely comfortable. A fun fact I’ve heard is that the number of rungs the hoop has, the wealthier the husband! The dress is cotton. The skirt, waistband pleats and floor hem are hand sewn. The Bodice is all machine sewn except for the hooks down the front. It was a lot of fun making, but stressful at times because the pattern was wonky.

Will you try another?

Since I’ve made one and worked out all of the kinks in reading patterns, I’d like to attempt a sheer for next year. We’ll see how that goes.

Who made the dress you wore at the reenactment we attended and that appears on “Beyond the Wood”?

It belonged to the wife of the 10th Michigan’s Colonel. Interestingly, her mother had made it for her wedding to the Colonel.

Do you see introducing living history to your children?

Yes. My Fiancé and I both deeply enjoy Civil War reenacting, and we are excited to continue it when we have a family of our own. It’s a great way to learn about our nation’s history, and it’s a constant learning experience.

Why do you think it important to learn and know about the Civil War?

The Civil War was a HUGE part of our nation’s history. And it still is, today. So many people think history is so dull and boring, but it’s really not. It’s fascinating! It’s enjoyable. It’s fun reading about people before us. It helps us figure out who we are and where we came from.

What’s your favorite part of reenacting?

My favorite parts of being a reenactor are the little girls that come up and say I look like a princess and those “Ah-Ha!” moments for spectators when I answer a question and a light bulb goes off for them–they’ve learned something they never knew or had a question cleared up.

We went to Gettysburg last summer for the 150th anniversary. It was amazing. So cool, and I got chills when we toured the battlefields. It was such an awesome experience! We learned so much more.

Do you have a favorite Civil War era hero/heroine?

We read a book in school called The Girl In Blue, by Ann Rinaldi. And while the story was fictional, it was based on the life of Sarah Emma Edmonds , which made me aware of all the women who gave up their identities to serve, and what they had to endure to keep their secrets safe. Based on The Girl in Blue, Sarah is my favorite.

Anything else you’d like to tell us about living history?

Just that I really love being a Civil War reenactor. I enjoy hanging out with my friends and family at events and crossing paths with wonderful people.

Thank you very much , Charlie. We’re particularly excited to hear of your plans for marriage and wish you all the best.

The post Living History: Getting Young People Involved appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

April 29, 2015

Stout’s “Upon the Altar of the Nation”: A Book Review

Earlier this year, I read Upon the Altar of the Nation: A Moral History of the Civil War by Harry S. Stout, Jonathan Edwards Professor of American Christianity at Yale University.

Earlier this year, I read Upon the Altar of the Nation: A Moral History of the Civil War by Harry S. Stout, Jonathan Edwards Professor of American Christianity at Yale University.

Professor Stout’s intent is to determine if the Civil War was a “just war.” I’m not sure he left me with a clear conclusion on that issue, however, he did give me a better feeling for the descent of both sides into the tragedy of precedent-setting “total war.” He does a great job of portraying citizens, clergy, press, politicians and generals descending into increased acceptance of spilled blood; while many eventually developed a near blood lust.

Stout Focuses on Total War

Stout contends Sherman’s march created animosity and long-term resistance among those in his path. (Library of Congress.)

Lincoln is presented as one of the few (maybe the only one) who maintains throughout “malice toward none,” although Stout holds the president ultimately responsible for eventual total war. But it is Grant and especially Sherman and Sheridan that Stout judges harshly, as related to taking the war to citizens. He blames Sherman’s march to the sea for creating more animosity and determination among those (especially the women) it affected directly. He even links the resentment of Sherman’s actions to the creation of the “Lost Cause.” And he reminds us that the “total war” justification was used by Grant/Sherman/Sheridan to slaughter men, women and children in their later, definitely unjust war against Native Americans.

Throughout, Stout presents the war as creating a secular national religion for both South and North that focuses on nation worship, with its blood sacrifices, its destiny and role as the great hope of the world, and finally with its martyred messiah in Abraham Lincoln.

I enjoyed reading quotes from sermons of ministers in North and South and gaining a better understanding of the role religion and its spokesmen played in the war culture. The most interesting and unexpected contention in the book was that the South was actually less religious than the North at the onset of the war, but that the war, revivals and conversions of Southern soldiers led to a dramatically increased religious society and culture when those same soldiers came home. Intriguing stuff.

The post Stout’s “Upon the Altar of the Nation”: A Book Review appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

April 14, 2015

Second Inaugural of Lincoln: A Book Review

My wife recently gave me a copy of Ronald C. White, Jr.’s book Lincoln’s Greatest Speech. It sat gathering proverbial dust, until I decided I should read something significant to mark the 150th anniversary of the president’s death.

My wife recently gave me a copy of Ronald C. White, Jr.’s book Lincoln’s Greatest Speech. It sat gathering proverbial dust, until I decided I should read something significant to mark the 150th anniversary of the president’s death.

Years ago I read Gary Wills’ majestic book on the Gettysburg address (which made my list of 25 favorite books about the Civil War). I thought this book would be a good companion, and it proved a worthwhile, enjoyable read. It started slowly and never revolutionized my perspective as the Wills book had years ago. However it did refine my thoughts about and appreciation for Lincoln and for his Second Inaugural.

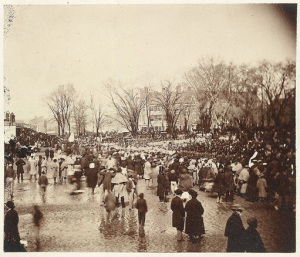

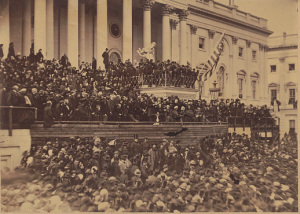

Crowd gathers on rainy morning of March 4, 1865 for Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. (Library of Congress)

The key takeaway from the book for me is to reaffirm the war changed Lincoln’s understanding of God. In his struggle to comprehend the meaning of the war, he found what he believed was greater clarity of the intent of God. He began to see a power higher than army or politician whose just purposes would somehow be fulfilled in the war.

White’s book reinforces my impression that Lincoln’s faith did grow substantially during the war. Those who counter that Lincoln was agnostic and spoke words that would resonate with his “religious” audience miss a key point. A speaker writing for the mood and background of his audience would never have given the Second Inaugural as Lincoln delivered did. His message and tone were not what the audience came for or perhaps clamored for.

It craved revenge. He spoke of “malice for none.”

It blamed the South. He “said there was blame that must be shared by the entire nation.”

It wanted to celebrate political, economic and military trouncing of a rebellious enemy who, after all, had started it all. Lincoln contended that the judgements of God were just and called the nation “to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan” both North and South.

Lincoln delivers an unexpected Second Inaugural speech of forgiveness and unity. (Library of Congress)

If Lincoln was agnostic, a theist or faithless, he was tone-deaf and dishonest. Perfect Lincoln was not perfect, but he was also not profoundly dishonest. Such dishonesty would have been required for him to speak such thoughtful words without believing and feeling them. In a man who over time proved forgiving and compassionate, we see no evidence of such inner corruption.

African-American soldiers among those who gathered for Second Inaugural. (Library of Congress)

In addition to a line by line analysis of the Second Inaugural, White gives us:

Interesting historical information and perspective on the speech and Lincoln’s background, e.g., Western Union finished its transcontinental telegraph at 3 am the day after the speech, enabling San Francisco to wake to next day reports of the speech.

Lincoln spoke in an unexpected tone. Contrasting with the expected bravado of the conqueror in both election and war, the president gave a humble speech that pointed blame for slavery at both sides and called for mercy, love and reunification. “When he delivered his Second Inaugural Address, he used personal pronouns only in the first paragraph, and from there on directed all attention away from himself.” Unlike the usual speeches after presidential reelection, he never thanked voters for returning him to office.

Every president before Lincoln had referenced God in some way, but only one had quoted a biblical phrase. “Lincoln would quote or paraphrase four Biblical passages.”

Both sides literally “read the same Bible.” Especially during early war days, Bibles (or more precisely New Testaments, because soldiers didn’t want the added weight/size of both testaments) were shipped from the North to both Yankee and Confederate soldiers, under flags of truce as they crossed lines.

Domestic journalistic reviews were mixed, but White quotes an American correspondent in Paris writing that many of the French envisioned the possibility after the war of “’a fleet of [American] gunboats sailing up the Seine to take Paris!” They were naturally reassured by the speech with its prayer for peace “with all nations.”

Many British newspapers had written supporting the Confederacy throughout the war, but after the speech, the London Spectator, “using Biblical imagery, opined that Lincoln ‘seems destined to be one of the “foolish things of the world” which are destined to confound the wise, one of the weak things which shall “confound the things which are mighty.”’”

White writes in the Epilogue “At the Second Inaugural… his words sum up the life and thought of the man….” and, “the Spirit of Lincoln’s words awe. His words prove lasting because he embodied what he spoke. He acted throughout his presidency ‘with malice toward none; with charity toward all.’”

The book is powerful because it highlights how the speech courageously broke with tradition of past presidents and speeches, was artfully and humbly written, and most importantly, was an expression of the inner man.

It becomes clear in the book that this speech was important to Lincoln and he believed it would be remembered. He wrote of the effort to Thurlow Weed, “’I expect the latter to wear as well—perhaps better than anything I have produced . . . but I believe it is not immediately popular.’”

The author quotes Frederick Douglass as telling the soon-to-be-”martyred” president, “Mr. Lincoln, that was a sacred effort.”

Lincoln’s life and inner man as shone through the Second Inaugural Speech was “a sacred effort” at living and in literary poetry. White helps us consider both a little more closely and leaves us much to ponder.

The post Second Inaugural of Lincoln: A Book Review appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

March 23, 2015

Reenacting the War: Kindling Understanding of the Past

Rolling hilltops peaked by reenactors and spectators in the morning sun of our first reenactment.

Just before the turn of the millennium, my wife and I rose early one Saturday to drive to our first Civil War reenactment. I don’t remember how long a drive it was, but the site was somewhere in Northern Virginia or West Virginia. We had of late been touring Civil War sites, and a reenactment seemed a logical extension.

The planned mock battle was a softened–thankfully–version of the Mule Shoe of Spotsylvania Courthouse.

Reenacting Union artist sketches artillery.

We enjoyed visiting reenactors at their morning fires, learning about their equipment and food, and the action of a mock battle with its artillery assaults, musketry and infantry and cavalry charges, where it seemed everyone, perhaps as in real life, was hesitant to die. As it turned out, the morning was worthwhile, both fun and, most importantly for us, educational.

Susan visits with Confederate reenactors over their morning fire.

Months later when we toured the Spotsylvania battlefield, we were, thanks to the reenactment, able to better visualize and maybe “feel” a bit more what soldiers must have experienced in those horrible days and hours at the Mule Shoe and the Bloody Angle.

From that first experience, my impressions of reenactments were completely positive (as long as I personally was not required to wear wool and sleep on the ground), and we’ve enjoyed a number of them since.

What I didn’t realize at the time is reenactments haven’t always been without opponents and controversy. In fact, they were sired amidst the bitter reconstruction of war memories.

Building “National” Unity by Reenacting

Within several years of the war, “sham battles were conducted purely as entertainment” with an underlying tone of national reconciliation. While these battles didn’t necessarily portray any specific battle, they often had “strong undertones of both sectional pride and national unity,” and to that end apparently never pitted Union and Confederate veterans against each other. In October 1889, 20,000 spectators watched 10 Georgia militia companies, 100 Confederate veterans and others stage a battle in which the Confederate veterans were allowed to win and a speaker proclaimed it all “a symbol of ‘the imperishable union of American hearts, and of the indissoluble union of American states, now and forevermore.’”¹

Left Out

In his analysis of the 1903 and 1937 reenactments of Petersburg’s Battle of the Crater, Kevin Levin argues that not everyone’s contributions were included in these reenactments. Specifically describing the 1903 reenactment, he wrote on his blog:

The day began with a procession through the streets of Petersburg. Spectators watched as the aged veterans, many displaying their wounds worked their way to the crest of the crater. Finally, they made their charge with a vibrant Rebel yell into what remained of the pit. For thirty minutes they reenacted the event in which they had been participants.²

African-Americans and their significant contribution and sacrifices (much of the sacrifice coming from Mead’s last-minute decision to not allow the black troops to lead the charge into the Crater, a role they had been briefed and trained for) in the battle were absent from the “celebration,” with only Stonewall Jackson’s former servant and cook marching in the parade, perhaps as a “comforting,” reinforcing message to the white audience.²

Levin contends that this obscuring of black soldier service at the Crater “stood in sharp contrast to the letters and diary entries written in the days and weeks following the battle. …Commenting on the dead black soldiers on the battlefield or the prisoners, one soldier described them as the ‘Blackest greaysest [greasiest] negroes I ever saw in my life.’ While stationed at Bermuda Hundred during the time of the battle, Edmund Womack wrote home to his wife, ‘I understand our men just chopped them to pieces.’ …Robert G. Evans of the 16th Mississippi recalled, ‘Most of the Negroes were killed after the battle. Some was killed after they were taken to the rear.’ Another soldier reported ‘the poor deluded devils were butchered right and left.’”²

But the event didn’t stop at ignoring black soldiers without a passing statement of degradation, as one speaker mentioned the “’brutal malice of negro soldiers.’”²

The reenactment of the Crater seemed to fit into a larger social effort to minimize and disparage anything to do with African-Americans in the war.

In 1907, “The National Tribune” newspaper carried an article by a Union officer who had led black troops at the crater. He wrote complaining about the continual blame black units received for the Crater debacle:

It may seem rather late in the day, 43 years after the battle of the Crater before Petersburg, to be condemning the colored troops who took part in that unsuccessful affair. It seems since the unhappy discharge of the colored battalion at Brownsville to be quite the fad when a party cannot find anything to hit or scold to make a shy at the colored troops, but those who condemn their action on that fatal day must remember that it was nearly three hours after the explosion before they were ordered in, time enough to get a regiment from New York to Philadelphia, and the enemy were plenty; they were right there; anything within 15 miles could have been rushed in during this time of waiting, and the Confederates were not slow; they had able generals, who were ready for any emergency. Again, the colored division had been specially drilled to lead the attack, and expected to until the last moment, when they were ordered back and another division of the Ninth Corps took their place.³

Centennial Reenactment Issues

By the 1930s, authenticity was beginning to creep into the reenactments, with “National Guard units, U.S. Marines, and military school cadets” using “contemporary military formations, uniforms, and weapons to re-create actual battles on or near the anniversary dates of the battles” including a 75th Chickamauga anniversary event that included “a historical pageant entitled ‘Drums of Dixie.’”¹

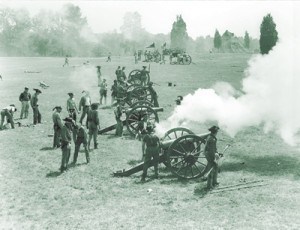

Confederate artillery reenactors fire their cannons at the Centennial Commemoration of the Battle of First Manassas. (Photo from Manassas National Battlefield Photographic File as posted on CivilWar.org)

But by the 1960s, the US was changing. Civil Rights and racial equality were rising issues and causes, and the Centennial celebration became a battlefront in the conflict.

The Centennial Commission, hoping to interest young people in “’their country’s history,’” sponsored an event to mark the 100th anniversary of First Bull Run. They also wanted to reinforce loyalty to the nation among all participants as the Cold War heated up and to promote national reconciliation. By many standards the event was a success, with 100,000 spectators watching the mock battle during a three-day period. But the commission didn’t realize the reenactments would be used “’to reinforce racial divisiveness within the South,’” with Southern reenactors in some cases cursing Union reenactors and “’many Confederate reenactors explicitly stat[ing] that it is the memory of the South that they reenact[ed].'” Unwittingly, commission sponsorship had “‘resuscitated the myth of the ‘lost cause,’ in which valiant citizens went to war to protect a ‘way of life,’ founded on another famous myth, the plantation romance.’”4

Criticizing it on other fronts, some thought the reenactment mocked the dead in a carnival-like setting that made farce of an incredible tragedy.4 I can understand those last perspectives. Safety of spectators and reenactors, some of whom received battlefield-like wounds, was also an issue at the event.5

But the cat was out of the bag, and the Manassas reenactment inspired hobbyists from the “the North-South Skirmish Association, a group of black-powder firearms buffs formed in 1950, who soon began forming their own groups devoted specifically to reenacting Civil War battles.” And it kept building.¹

Reenacting a cavalry clash.

I’m not a reenactor, but I’ve never seen any Lost-Cause promotion or racial prejudice among the reenactors I’ve met and visited with. In fact, I’ve noticed more African-Americans getting into the hobby, one reporting, “Most reenactors, whether Union or Confederate, black or white, are considerate of each other. Many white reenactors tell us that they are glad that we are here to tell the USCT [United States Colored Troops] side of the story.”6

Union artillery reenactors being filmed.

All this brings me back to my first reenactment experience (and every one since then): I do think exposure to reenactments can be the genesis of a love of history and a source of deepening understanding, and I’m grateful to the men, women, young and old, who dedicate so much time and energy to recreating the historical Civil War with their portrayals of era soldiers and civilians.

What do you think?

In my next blog or two, I’ll take a look at folks who engage in Civil War living history.

Sources:

1 Jones, Gordon L. “Civil War Reenacting.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 10 January 2014. Web. 18 March 2015. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/civil-war-reenacting

2 Levin, Kevin. “Landscapes and the Lost Cause: An Analysis of the 1903 and 1937 Crater Reenactments.” Civil War Memory. April 11, 2006. Web. 18 March 2015. http://cwmemory.com/2006/04/11/landscapes-and-the-lost-cause-an-analysis-of-the-1903-and-1937-crater-reenactments/

3 Proctor, D. E. “ The Massacre in the Crater .” National Tribune 17 October 1907. 6:3-4. (as transcribed by Weeks, Michael. “NT: October 17, 1907 National Tribune: The Massacre in the Crater.” The Siege of Petersburg Online. Web. March 19, 2015. http://www.beyondthecrater.com/resources/nt/siege-of-petersburg-nt/nt-19071017-the-massacre-in-the-crater/

4 Gough, Kathleen M. Plantation and America’s “alienated cousins”: Trinidad carnival and Southern Civil War reenactments. Just below South: intercultural performance in the Caribbean and the U.S. South. Edited by Jessica Adams, Michael P. Bibler, and Cecile Accilien. (University of Virgina. 2007). pp. 167-188. Web. 17 March 2015. https://www.academia.edu/5363511/Plantation_Americas_Alienated_Cousins_Trinidad_Carnival_and_Southern_Civil_War_reenactments

Relevant sources and notes from Gough’s work:

John Bodnar. Remaking American: Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000).

Michael Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture (New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 593.

All the files of the Civil War Centennial Commission are located at the National Archives II, in College Park, Record Group 79: Records of the National Park Service: Civil War Centennial Commission Subject Files, 1957-1966. Letter from Box 96, Record Group 79, dated Oct. 5, 1962. The information on spectatorship was found in the caption attached to a photo of the reenactment of the Battle of Manassas in the Photographs (Still Picture Archive), Box 5: CWCC 1947-1965 in record group 7.

Rory Turner, “Civil War Reenactments and Their Use of History,” Folklore Forum 22, nos. 1 and 2 (1989), 58.

Tara McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender, and Nostalgia in the Imagined South (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2003), 19.

Frank E. Vandiver, “The Confederate Myth,” in Myth and Southern History, vol. 1, The Old South, ed. Patrick Gerster and Nicolas Cords (Chicago: University of Illinois, 1989), 148.

5 Reid, John. “The Centennial Reenactment of First Manassas: Blood in Bull Run: The Battlefield Today.” CivilWar.org. Hallowed Ground Magazine. Spring 2011. Web. 20 March 2015. http://www.civilwar.org/hallowed-ground-magazine/spring-2011/the-centennial-reenactment-manassas.html

6 Henderson, Steward T. “My Life as a Black Civil War Living Historian–Part Six.” Emerging Civil War. 18 June 2013. Web. 20 March 2015. http://emergingcivilwar.com/2013/06/13/my-life-as-a-black-civil-war-living-historian-part-six/

The post Reenacting the War: Kindling Understanding of the Past appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

March 2, 2015

Fighting for Both Sides During the Civil War

Tennessee residents John Jones and Daniel Parrott started out fighting under the Stars and Bars, but both changed sides and finished the war under the Stars and Stripes.

Recently while doing family history, I sought information on a Daniel Parrot who hailed from the mountain hollows of East Tennessee.

I’d heard Daniel was a Unionist and was interested in getting more information on him because his affiliation seemed to contrast with his brother James—a direct family ancestor—who chose the Confederacy. After less than a year in the army, James died of smallpox near Jackson, Mississippi, just before Vicksburg surrendered in July 1863.¹

But the contrast between the brothers didn’t develop as I expected as one of Daniel’s descendants, Bill D. Jones, wrote to me that Daniel did fight for the Union, but only after fighting for the Confederacy.² My curiosity was aroused.

During a visit to the LDS Family History Library in Salt Lake City, I found more information on Daniel’s disloyalty and, while looking for other family ancestors in East Tennessee, stumbled on the tragic story of John Jones abandoning the Confederacy for a blue uniform.³

Thousands Fought for Both Sides

The stories of these two men raised my interest in and awareness of the soldiers who fought on both sides. Men like Sam Sixkiller of the Cherokee Nation, who fought first for the Confederates, but later changed sides to fight for the Union.4

Or the about 6,000 Galvanized Yankees, former Confederate prisoners of war who agreed to take the Oath of Allegiance and switch sides for liberation from Northern prisons.5 For their freedom, they enlisted in one of six special Union regiments composed of former Confederate soldiers and were sent west “where they quelled Indian uprisings, protected settlers, restored stage and mail service, guarded railroad survey parties, provided escort service for supply trains, and rebuilt telegraph lines.”6

Each one of the thousands that fought for both sides must have had their own unique story, but here are Daniel’s and John’s, both residents of a rough border state where, I suspect, allegiance was always suspect and many chose or were forced to reconsider their original alliances.

If you know stories of other men (or women) who fought for both sides during the war, I’d love to hear them.

Daniel Parrott: Confederate “Forced” into Yankeedom

Daniel was born in 1841 in Hawkins County, Tennessee, and married Elizabeth “Lizzy” Bean October 6, 1862.7 But by the time of their marriage, he was already a Confederate soldier, having mustered August 15, 1861 and serving in K Company, 19th Regiment, Tennessee Infantry. A private, he served as a teamster and received a serious injury to his hip or groin September 19, 1863 at Chickamauga. From that time till at least June 1864, he was recovering either in the hospital or at home. According to family tradition, in late September he was at home when Union soldiers came to his home and told him “he was coming with them or they would kill him and his [pregnant] wife.”8

He accepted their invitation to change sides—we don’t know how willingly—and on October 1, 1864 joined K Company, 13th Tennessee Volunteer Cavalry (irony of a volunteer unit noted) and served the Union until September 5, 1865.8

Daniel’s story of “loyalty issues” only gets more interesting, however, after the war ends. He lives with Lizzy till 1885 when he leaves for a short trip because of his father’s death. But he’s gone for more than a decade. Lizzy, with whom he had nine children, assumed he was dead, but he wasn’t and by 1900 he had returned to live with her. They lived as man and wife till his death in 1911. By that time, however, she knew that while he was gone, he had married two other women, one in Kentucky and one in Arkansas.8

After Lizzy was granted a pension in 1911, a special examiner looked into the circumstances and reported:

The soldier was married to the claimant in 1862 and deserted her in 1885, going to Kentucky, where he married Louisa Bruner in May, 1886. She died in August, 1886, and in Dec. 1887, or 1888, he married America E. Morris, with whom he lived till 1899, and then deserted her and returned to his first wife, the claimant in this case.

…The claimant is 73 years old. She is so crippled from rheumatism that she has to use two crutches. She is almost totally blind and is otherwise in feeble health. She is absolutely penniless. She is taken care of by her daughter and son-in-law, who are very poor and have five children of their own.

They all live in a little hut. I think that this claim should be made special.

Claimant bears an excellent reputation for truthfulness, and no one has a word to say against her character, except some blame her for taking the soldier back.8

Blame her for taking him back or not, however, there is no doubt her case was definitely special with regard to this soldier who fought for both sides.

John Jones: Disillusioned Rebel Chooses a New Uniform

John Jones’s Union service is recorded on his tombstone, where he is buried with his wife. His grave also boasts a star from the Grand Army of the Republic.

Both John Jones and Jerusha Surgener were born in 1835 in East Tennessee. They got married in 1853.9 Early on John joined the Confederate army, but lost faith in the cause, deserted and mustered into the Union army, joining Company H of the 8th Tennessee Cavalry.³

In 1865 while John was away with the army, Jerusha caught pneumonia and died.9 John returned home for her wake, but was abducted by 25 Confederate soldiers who, led by one Jess Henard, crashed the event, capturing John and three other Union men. The soldiers loaded John and the others into a wagon and “took them towards Surgoinsville.” All four men attempted escape during the night, and each was shot dead.³ “Martin Crawford was charged” with John’s “murder” but was acquitted 9 as it was “declared an act of war and all charges were dropped.”³

John and Jerusha were buried together, leaving behind at least four children, orphaned by the war.

In the end nearly everyone returned to the Union, so it’s circumstances and timing that make these stories stand out.

Don’t forget, I’d love to hear the stories of other soldiers who fought for both sides and why they did it.

Sources:

¹Familysearch.org. James Parrott. Family Search. Web. 18 February 2015. https://familysearch.org/tree/#view=ancestor&person=KZXG-W8S

²Jones, Bill D. “Daniel Parrott.” Message to Michael Roueche. 12 January 2015. E-mail.

³Brandon, Connie B. Step Back in Time to Laurel Gap/Bailyton (Late 1700’s through Early 1900’s) in Greene County, Tennessee. 2005. Print.

4Wikia.com. Sam Sixkiller. Wikia. Web 19 February 2015. http://civilwar.wikia.com/wiki/Sam_Sixkiller

5History.com. 6 Southern Unionist Strongholds During the Civil War. History. Web 19 February 2015. http://www.history.com/news/history-lists/6-unionist-strongholds-in-the-south-during-the-civil-war

6CivilWarSoldierSearch.com. Galvanized Yankees. Civil War Soldier Search. Web 19 February 2015. http://civilwarsoldiersearch.com/galvanized-yankees.html

7Familysearch.org. Daniel Henry Parrott. Family Search. Web. 18 February 2015. https://familysearch.org/tree/#view=ancestor&person=22TS-WTY

8Garner, Hallie Price. The Bean Tree: descendants of John Bean of Hawkins County, Tennessee. Dallas, Texas: Garner Services. 2009. Print.

9Findagrave.com. John Jones. Find a Grave. Web. 18 February 2015. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=74090213

The post Fighting for Both Sides During the Civil War appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

January 28, 2015

The Civil War: Appealing to God

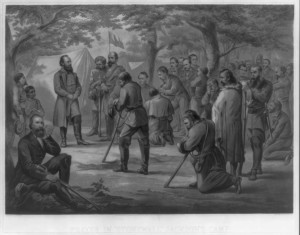

Prayer in “Stonewall” Jackson’s Camp.

“Both [Confederacy and Union] read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other.”

Abraham Lincoln

A few weeks ago I posted the story of Lieutenant J. M. Waddill which boasted multiple amazing coincidences and/or the hand of God. Which was it?

Whenever I look at the war, both details and overall flow, I come away with the clear impression that an invisible hand intervened throughout, first to prolong the war and then to bring it to a conclusion that solidified perpetual union; a strong Federal government; and freedom and a promise of future equal opportunity for men and women held in race-based slavery.

I, among other things, think of Stonewall Jackson being just in the right place and holding the line at First Manassas, A. P. Hill arriving “in the nick of time” to save Lee at Antietam, the Confederates beating the Union forces to Laurel Hill by minutes, and even the assassination of Lincoln which came just after his strength and unwavering determination had for practical purposes brought victory to the North.

America in the 1860s identified itself as a devoutly religious–most often specifically as a Christian–nation. As the war between two Christian-based regional social orders heated up, increased “devotion” to God followed. Both North and South vied for the claim of Heaven’s support and for Deity’s actual benediction. Each endeavored to see any outcome as a blessing from God, an endorsement of the nation or, at times, as a warning to repent. “Both sides needed to enlist God in their cause as both justifier and absolute guarantor of their deliverance.”(1)

Almighty God is in the Constitution

While the Declaration of Independence references a Creator, the framers of the US Constitution did not include mention God or Jesus. The South, perhaps in response, sought to justify its aspirations by “explicitly declar[ing] its Christian identity, ‘invoking the favor and guidance of Almighty God.’ The national motto, Doe (sic) Vindice (‘With God as our defender’), added weight to the South’s claim to be a uniquely Christian nation.”(2)

But the Confederacy went further, finding public fault with the Union’s supposed Constitutional lack of reverence for the Deity and taking pride in its own Constitutional reference to God. Preacher Edward Reed sermonized in South Carolina, “’Whether through inadvertence, or, as is unfortunately more probable, from infidel practices imbibed in France by some members of the Convention . . . [the US Constitution] contained no recognition to God. Our present Constitution opens with a confession of the existence and providence of the Almighty.”(3)

Inclusion of reference to God in the Southern Constitution created a drive to add the Almighty to the North’s ruling document. “With Confederate sanctimoniousness in mind, Northern evangelicals rehearsed the case for a constitutional amendment in the North that would invoke God.”(4)

The ultimately unsuccessful drive reached the White House, where “on Dec. 3, 1864, Abraham Lincoln proposed putting God in the Constitution. Preparing to submit his annual address on the state of the union, the president drafted a paragraph suggesting the addition of language to the preamble ‘recognizing the Deity.'”(5) The proposal, however, didn’t make it past cabinet discussion.

Petitioning God Through Fasts

With or without mention of God in the Constitution, both sides appealed to God in prayer, days of thanksgiving and nationally dedicated days of fast. “Theologically, ministers agreed that fasts or thanksgivings could not magically ensure earthly triumphs. But when victories came, they simply could not resist the assumption that their piety had commended–or at least cajoled—God’s orchestration of events in the field. Had a defeat followed the fast, ministers would either say nothing or complain that the people were not sufficiently sincere.”(6)

Two Presidents Turn to God

As has been well and sometimes controversially documented, the war seems to have brought both Davis and Lincoln to personally contemplate the role of the Heavenly Father in life and the War. Davis was baptized and confirmed in the Episcopal Church May 6, 1862,(7) and Lincoln’s faith deepened and changed as he recognized God’s hand and purpose in the war.(8)

“A deeply frustrated Lincoln questioned himself and turned for direction to his God. Like Davis, Lincoln was becoming steadily more spiritual, although without compromising his unshaken resolve. …Increasingly he sensed that something more than a mere civil war was going on in this conflict, and that it transcended the rightness or wrongness of either side. Northern clergy and opinion shapers might be certain that God was on their side, but Lincoln, almost alone, was not convinced. He too had a growing sense of Providence, but without the selfrighteous evangelical piety that went along with so much patriotism in the North and the South.”(9)

My Conclusion

Society, in general, during the Civil War seems to have believed in a personal God, expecting him to influence and guide people’s lives. Lincoln’s Second Inaugural pointed out the obvious reality that citizens of both sides were appealing to the same God. Was adding Deity to a constitution, or prayers fasts and days of thanksgiving effective?

On the national level, it clearly didn’t work for the South, and it didn’t work out as quickly or even as most in the North desired. But I suspect from my personal experience, turning to God in the Civil War brought intervention and blessings to the lives of individuals and families. Lincoln, himself, seems to have moved closer through the war to a recognition that God was influencing and directing lives.

From my viewpoint, God’s hand was intimately involved in the unlikely story of J.M. Waddill and in the Civil War. I think Lincoln got it right in his Second Inaugural: “The Almighty has His own purposes” in the war.(10) The president was capturing what Isaiah taught millennia ago, “For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways.”(11)

The Civil War is a sacred experience, dedicated now to the freedom of all men. It reminds me that the United States is exceptional, not for what any of us have done, but because of the freedoms a Divine hand has given us. It is a call to each of us, as it were, to be a light to the world, that someday all nations and all men and women will seek freedom for the entire human race.

What do you think?

Sources and Notes:

(2) Stout. 47.

(3) Reed, Edward. A People Saved by the Lord. Charleston, 1861. (qtd. In Stout, etc. 74).

(4) Stout. 77.

(5) Moore, Joseph S. “Lincoln, God and the Constitution”. The New York Times. December 4, 2014. nytimes.com. <http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/12/04/lincoln-god-and-the-constitution/?>

(6) Stout. 135.

(7) “A Day in History: Timeline” The Papers of Jefferson Davis. Rice University, 2011.. Web. 25 January 2015 <http://jeffersondavis.rice.edu/timeline/>.

(8)For a detailed discussion of Lincoln’s beliefs concerning Diety at the time of his Second Inagural Address, see:

Calhoun, Samuel W. and Morel, Lucas E. “Abraham Lincoln’s Religion: The Case for His Ultimate Belief in a Personal, Sovereign God”. Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. Volume 33, Issue 1, Winter 2012, pp. 38-74. <http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.2629860.0033.105>

See also Wolf, William J. “Abraham Lincoln’s Faith”. The Lincoln Institute Presents: Abraham Lincoln’s Classroom. Web. 24 Jan. 2015 <http://abrahamlincolnsclassroom.org/abraham-lincoln-in-depth/abraham-lincolns-faith/>

(9) Stout. 145.

(10) Lincoln, Abraham. “Second Inaugural Address”. Web. Bartleby.com. 10 Jan. 2015. <http://www.bartleby.com/124/pres32.html>

(11) Isaiah 55:8

The post The Civil War: Appealing to God appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

January 12, 2015

An Amazing, Inspiring Elmira Prison Story and a Question

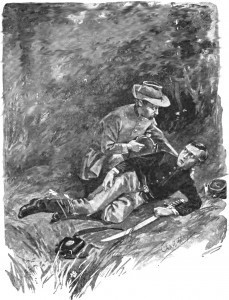

Confederate Lieutenant J. M. Waddill gives canteen to injured Union soldier during 1864 Wilderness Battle. Illustration taken from 1896 edition of Under Both Flags.

Confederate Lieutenant J. M. Waddill tells a story that begins May 5, 1864k in the middle of the Civil War’s Wilderness Battle.¹

In that battle, his unit lost its captain and first lieutenant, leaving Waddill in command. He was ordered to move his men to the rear, where they were charged with protecting a wagon train from an anticipated enemy cavalry raid, which never came.