Reenacting the War: Kindling Understanding of the Past

Rolling hilltops peaked by reenactors and spectators in the morning sun of our first reenactment.

Just before the turn of the millennium, my wife and I rose early one Saturday to drive to our first Civil War reenactment. I don’t remember how long a drive it was, but the site was somewhere in Northern Virginia or West Virginia. We had of late been touring Civil War sites, and a reenactment seemed a logical extension.

The planned mock battle was a softened–thankfully–version of the Mule Shoe of Spotsylvania Courthouse.

Reenacting Union artist sketches artillery.

We enjoyed visiting reenactors at their morning fires, learning about their equipment and food, and the action of a mock battle with its artillery assaults, musketry and infantry and cavalry charges, where it seemed everyone, perhaps as in real life, was hesitant to die. As it turned out, the morning was worthwhile, both fun and, most importantly for us, educational.

Susan visits with Confederate reenactors over their morning fire.

Months later when we toured the Spotsylvania battlefield, we were, thanks to the reenactment, able to better visualize and maybe “feel” a bit more what soldiers must have experienced in those horrible days and hours at the Mule Shoe and the Bloody Angle.

From that first experience, my impressions of reenactments were completely positive (as long as I personally was not required to wear wool and sleep on the ground), and we’ve enjoyed a number of them since.

What I didn’t realize at the time is reenactments haven’t always been without opponents and controversy. In fact, they were sired amidst the bitter reconstruction of war memories.

Building “National” Unity by Reenacting

Within several years of the war, “sham battles were conducted purely as entertainment” with an underlying tone of national reconciliation. While these battles didn’t necessarily portray any specific battle, they often had “strong undertones of both sectional pride and national unity,” and to that end apparently never pitted Union and Confederate veterans against each other. In October 1889, 20,000 spectators watched 10 Georgia militia companies, 100 Confederate veterans and others stage a battle in which the Confederate veterans were allowed to win and a speaker proclaimed it all “a symbol of ‘the imperishable union of American hearts, and of the indissoluble union of American states, now and forevermore.’”¹

Left Out

In his analysis of the 1903 and 1937 reenactments of Petersburg’s Battle of the Crater, Kevin Levin argues that not everyone’s contributions were included in these reenactments. Specifically describing the 1903 reenactment, he wrote on his blog:

The day began with a procession through the streets of Petersburg. Spectators watched as the aged veterans, many displaying their wounds worked their way to the crest of the crater. Finally, they made their charge with a vibrant Rebel yell into what remained of the pit. For thirty minutes they reenacted the event in which they had been participants.²

African-Americans and their significant contribution and sacrifices (much of the sacrifice coming from Mead’s last-minute decision to not allow the black troops to lead the charge into the Crater, a role they had been briefed and trained for) in the battle were absent from the “celebration,” with only Stonewall Jackson’s former servant and cook marching in the parade, perhaps as a “comforting,” reinforcing message to the white audience.²

Levin contends that this obscuring of black soldier service at the Crater “stood in sharp contrast to the letters and diary entries written in the days and weeks following the battle. …Commenting on the dead black soldiers on the battlefield or the prisoners, one soldier described them as the ‘Blackest greaysest [greasiest] negroes I ever saw in my life.’ While stationed at Bermuda Hundred during the time of the battle, Edmund Womack wrote home to his wife, ‘I understand our men just chopped them to pieces.’ …Robert G. Evans of the 16th Mississippi recalled, ‘Most of the Negroes were killed after the battle. Some was killed after they were taken to the rear.’ Another soldier reported ‘the poor deluded devils were butchered right and left.’”²

But the event didn’t stop at ignoring black soldiers without a passing statement of degradation, as one speaker mentioned the “’brutal malice of negro soldiers.’”²

The reenactment of the Crater seemed to fit into a larger social effort to minimize and disparage anything to do with African-Americans in the war.

In 1907, “The National Tribune” newspaper carried an article by a Union officer who had led black troops at the crater. He wrote complaining about the continual blame black units received for the Crater debacle:

It may seem rather late in the day, 43 years after the battle of the Crater before Petersburg, to be condemning the colored troops who took part in that unsuccessful affair. It seems since the unhappy discharge of the colored battalion at Brownsville to be quite the fad when a party cannot find anything to hit or scold to make a shy at the colored troops, but those who condemn their action on that fatal day must remember that it was nearly three hours after the explosion before they were ordered in, time enough to get a regiment from New York to Philadelphia, and the enemy were plenty; they were right there; anything within 15 miles could have been rushed in during this time of waiting, and the Confederates were not slow; they had able generals, who were ready for any emergency. Again, the colored division had been specially drilled to lead the attack, and expected to until the last moment, when they were ordered back and another division of the Ninth Corps took their place.³

Centennial Reenactment Issues

By the 1930s, authenticity was beginning to creep into the reenactments, with “National Guard units, U.S. Marines, and military school cadets” using “contemporary military formations, uniforms, and weapons to re-create actual battles on or near the anniversary dates of the battles” including a 75th Chickamauga anniversary event that included “a historical pageant entitled ‘Drums of Dixie.’”¹

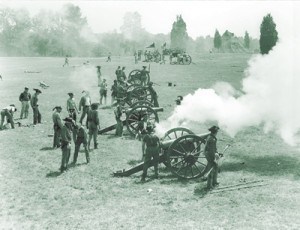

Confederate artillery reenactors fire their cannons at the Centennial Commemoration of the Battle of First Manassas. (Photo from Manassas National Battlefield Photographic File as posted on CivilWar.org)

But by the 1960s, the US was changing. Civil Rights and racial equality were rising issues and causes, and the Centennial celebration became a battlefront in the conflict.

The Centennial Commission, hoping to interest young people in “’their country’s history,’” sponsored an event to mark the 100th anniversary of First Bull Run. They also wanted to reinforce loyalty to the nation among all participants as the Cold War heated up and to promote national reconciliation. By many standards the event was a success, with 100,000 spectators watching the mock battle during a three-day period. But the commission didn’t realize the reenactments would be used “’to reinforce racial divisiveness within the South,’” with Southern reenactors in some cases cursing Union reenactors and “’many Confederate reenactors explicitly stat[ing] that it is the memory of the South that they reenact[ed].'” Unwittingly, commission sponsorship had “‘resuscitated the myth of the ‘lost cause,’ in which valiant citizens went to war to protect a ‘way of life,’ founded on another famous myth, the plantation romance.’”4

Criticizing it on other fronts, some thought the reenactment mocked the dead in a carnival-like setting that made farce of an incredible tragedy.4 I can understand those last perspectives. Safety of spectators and reenactors, some of whom received battlefield-like wounds, was also an issue at the event.5

But the cat was out of the bag, and the Manassas reenactment inspired hobbyists from the “the North-South Skirmish Association, a group of black-powder firearms buffs formed in 1950, who soon began forming their own groups devoted specifically to reenacting Civil War battles.” And it kept building.¹

Reenacting a cavalry clash.

I’m not a reenactor, but I’ve never seen any Lost-Cause promotion or racial prejudice among the reenactors I’ve met and visited with. In fact, I’ve noticed more African-Americans getting into the hobby, one reporting, “Most reenactors, whether Union or Confederate, black or white, are considerate of each other. Many white reenactors tell us that they are glad that we are here to tell the USCT [United States Colored Troops] side of the story.”6

Union artillery reenactors being filmed.

All this brings me back to my first reenactment experience (and every one since then): I do think exposure to reenactments can be the genesis of a love of history and a source of deepening understanding, and I’m grateful to the men, women, young and old, who dedicate so much time and energy to recreating the historical Civil War with their portrayals of era soldiers and civilians.

What do you think?

In my next blog or two, I’ll take a look at folks who engage in Civil War living history.

Sources:

1 Jones, Gordon L. “Civil War Reenacting.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 10 January 2014. Web. 18 March 2015. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/civil-war-reenacting

2 Levin, Kevin. “Landscapes and the Lost Cause: An Analysis of the 1903 and 1937 Crater Reenactments.” Civil War Memory. April 11, 2006. Web. 18 March 2015. http://cwmemory.com/2006/04/11/landscapes-and-the-lost-cause-an-analysis-of-the-1903-and-1937-crater-reenactments/

3 Proctor, D. E. “ The Massacre in the Crater .” National Tribune 17 October 1907. 6:3-4. (as transcribed by Weeks, Michael. “NT: October 17, 1907 National Tribune: The Massacre in the Crater.” The Siege of Petersburg Online. Web. March 19, 2015. http://www.beyondthecrater.com/resources/nt/siege-of-petersburg-nt/nt-19071017-the-massacre-in-the-crater/

4 Gough, Kathleen M. Plantation and America’s “alienated cousins”: Trinidad carnival and Southern Civil War reenactments. Just below South: intercultural performance in the Caribbean and the U.S. South. Edited by Jessica Adams, Michael P. Bibler, and Cecile Accilien. (University of Virgina. 2007). pp. 167-188. Web. 17 March 2015. https://www.academia.edu/5363511/Plantation_Americas_Alienated_Cousins_Trinidad_Carnival_and_Southern_Civil_War_reenactments

Relevant sources and notes from Gough’s work:

John Bodnar. Remaking American: Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000).

Michael Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture (New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 593.

All the files of the Civil War Centennial Commission are located at the National Archives II, in College Park, Record Group 79: Records of the National Park Service: Civil War Centennial Commission Subject Files, 1957-1966. Letter from Box 96, Record Group 79, dated Oct. 5, 1962. The information on spectatorship was found in the caption attached to a photo of the reenactment of the Battle of Manassas in the Photographs (Still Picture Archive), Box 5: CWCC 1947-1965 in record group 7.

Rory Turner, “Civil War Reenactments and Their Use of History,” Folklore Forum 22, nos. 1 and 2 (1989), 58.

Tara McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender, and Nostalgia in the Imagined South (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2003), 19.

Frank E. Vandiver, “The Confederate Myth,” in Myth and Southern History, vol. 1, The Old South, ed. Patrick Gerster and Nicolas Cords (Chicago: University of Illinois, 1989), 148.

5 Reid, John. “The Centennial Reenactment of First Manassas: Blood in Bull Run: The Battlefield Today.” CivilWar.org. Hallowed Ground Magazine. Spring 2011. Web. 20 March 2015. http://www.civilwar.org/hallowed-ground-magazine/spring-2011/the-centennial-reenactment-manassas.html

6 Henderson, Steward T. “My Life as a Black Civil War Living Historian–Part Six.” Emerging Civil War. 18 June 2013. Web. 20 March 2015. http://emergingcivilwar.com/2013/06/13/my-life-as-a-black-civil-war-living-historian-part-six/

The post Reenacting the War: Kindling Understanding of the Past appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.