Michael J. Roueche's Blog, page 3

May 19, 2014

“Ain’t Misbehavin’” on Online Book Tour

Oh, yes I am. I have officially misbehaved. I note this so you’ve been warned.

I heard your comment, “That’s unusual—the misbehaving.”

Precisely. You’re wondering about the cause of this misbehavior? Laziness!

“Laziness?”

Your stare is making me uncomfortable. Please make this little confession a little easier on me: Glance away from the computer screen. There, that’s better.

Yes, laziness, and here’s the story: Author Robin Nolet invited me to join a book tour. I told her I would. I was supposed to answer some questions (and I will momentarily), and point you on to three other websites of authors who I contacted in advance to invite on the tour. Didn’t do it.

“Surely, you just forgot.”

I appreciate that a kind gaze and your giving me the benefit of the doubt (Very charitable!), but I didn’t forget. It was that laziness I confessed to earlier. Is that disappointment I see in your expression?

“If you’re too lazy to follow the rules, maybe I should be too lazy to read anymore of what you’ve written here (or your books)! After all, there are lots of other authors I could be reading about, authors who follow the rules and aren’t lazy.”

You’re right, and I wouldn’t blame you if you click to some other site right now. Might I suggest one: Robin’s blog (www.robinnolet.blogspot.com). She’s got a couple of books under her belt, and she’s working on a sequel to her first The Shell Keeper, a look at women’s lives and relationships. That’s not a genre I visit, but her second book—a mystery—Framed is a good escape, quick read and fun who-done-it. I am a huge fan of mysteries (mostly the British television versions, although I am currently reading the English detective genre’s first and influential effort—written in 1868: Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone; free Kindle version available), so I had a good time in Nolet’s book, trying to guess the guilty, clear the innocent and avoid murder in the small town of Tallman, Colorado. I’m looking forward to her next Kay Conroy Mystery.

Now here are the questions I’m supposed to answer:

What am I working on?

We had a great time and met some new friends last week at a book club in Castle Rock, Co. Its members wanted to make sure I tied up all the loose ends in the Beyond the Wood Series.

I’m writing the final installment of the Beyond the Wood Series. I’ve got a working title, but no final name. I was with a book club in Castle Rock, CO, last week, and our conversation, besides being very fun, reminded me how careful I need to be in finishing the series. I assured them my wife had already given me a list of loose story strings (a page long!) that have to be tied up by the end. (I fear I’ll have to spend entire book just answering the as-yet unresolved.)

How does my work differ from others of its genre?

I try to thread the needle of appealing to a broader audience by including both Civil War social and important war scenes and try to make the backdrop as accurate as I can. A while ago I got an email from a woman who enjoyed the book and was asking how to pronounce my name (pronounced to rhyme with touché). She told me she had just given the book to her Civil-War-bluff husband to read. Several days later I got another email from her, indicating that her husband had pronounced it a “worthwhile read.”

Why do I write what I do?

Pure happenstance at the confluence of three experiences:

Over a several-year time period, I’d been reading extensively about the Civil War.

During that time, a friend randomly handed me a replica of a Virginia Militia uniform button, insisting I keep it. (You can see a photo of the button on the spine and back cover of Beyond the Wood.)

And finally, during a spur-of-the-moment drive toward Virginia’s Manassas National Battlefield Park, we met a man just outside the park. He was missing a leg—reminding me instantly of Confederate General Richard S. Ewell who lost a leg at the battle at Brawner’s Farm, prelude to Second Bull Run. Meeting the man was an interesting coincidence, not extraordinary. But the man’s sudden disappearance was. (Yes, I’ve since figured out how it could have happened.)

The outline for Beyond the Wood came to me at the moment our new friend disappeared.

How does your writing process work?

Randomly. It is a great pleasure to be in the 19th century, but it’s difficult to get there. Almost anything distracts me, because almost anything is always easier than creating and structuring a story. I especially get distracted with questions, e.g. “When was gas light added in Winchester, Va?” Such questions lead to hours of searching and peripheral questions that come up along the way and are just too interesting to leave unanswered. Research is just much too easy with the internet. I write in the morning and can write late in the evening, but my mind is too muzzy in the afternoons to write.

In keeping with breaking the rules, here are a couple of author sites and books you may want to check out (even though I didn’t invite them to participate in the book tour):

Tracy Groot just released a Civil War historical fiction book about notorious Anderson Prison—The Sentinels of Andersonville. Booklist Review calls it “well-researched, inspirational, historical tale…compelling and memorable for a diverse audience.”

Julianne Donaldson has two books out, including her latest Jane Austinesque novel, Blackmoore, which Publisher’s Weekly rates as “riveting and evocative.”

The post “Ain’t Misbehavin’” on Online Book Tour appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

April 22, 2014

Sitting by a Dead Man

Shakespeare’s burial-stone curse–”Cursed be he that moves my bones”–must have worked for he rests by his wife, Anne, and has been undisturbed by everyone but hordes of tourists and worshipers in Stratford-upon-Avon’s Holy Trinity Church.

I’ve just spent two years sitting beside what is left of William Shakespeare, and considering he’s been in sepulchral decay just shy of 450 years, there’s still quite a bit of him to sit by.

It was a project, inspired by the 2012 “Talk Like Shakespeare Day” proclamation in Chicago. Familiarity with the old Quaker Oats commercial and the King James Bible made it easy for me to pretend I could speak “Shakespeare” with a few “thees,” “thous,” and “wouldst” tossed in mundane 21st-century English. I tried a few phrases on my wife. Impressed, she was not. I could tell by the way she ignored me. This was not right!

I determined I could do better, and I gave myself two years to ready for my next foray in overwhelming my wife’s auditory senses. Thus hatched my quest to read and blog about all Shakespeare’s works before the 450th anniversary of his birth. It was really no great challenge to read him in two years. Many had read all of them before, and I was highly motivated: I’d be able to woo her with romantic phrases, entertain her with perfectly structured insults and inspire her with heroic monologues. So, I scooted over by the man, hoping some of his mastery would seep like methane gas from a landfill into me.

Two years have passed, Shakespeare is now (probably) 450 years old: Today’s the day I try again to impress my wife with

William Shakespeare was baptized and buried in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon. Between the two events, he gave the world just a bit of poetry, romance, horror, gallantry, humor, love, lust, patience and ambition in some pretty good plays.

Shakespearean-like prose and poetry. Should I impress her with Portia-like words on justice and mercy? Or lift a few of bad-boy Harry V’s words to sprinkle in: Perhaps a nice discussion of the challenges we face together against enormous odds—I could weave in a bit about we two, “we happy few.” I have even considered provoking an argument in eloquent Elizabethan words demanding that she acknowledge that the sun is really the moon, but if I were to do that, I’m pretty sure we’d no longer be the happy two. I’m still weighing my options, with few minutes left to decide.

While I consider what to say to her, let me acknowledge my great love and respect for my new friend and dehydrated mentor and mention a few things a Shakespeare novice learned about the poet, his work and us in the last couple of years.

Shakespeare’s plays were not meant to be read; they were meant to be performed and watched. But they have to be read to give one time to examine the ideas and words he tinkered with. I found I got much more out of the plays when I watched them performed (when I could), then read them.

Shakespeare was not meant to be watched or read out of context of his times. The more I read Shakespeare’s plays, the more I wanted to know about the historical background and the culture and practices of his day, and the more I learned about the history and his times, the more I understood and appreciated the plays, their author and Elizabethan and Jacobean England.

The question that kept creeping into my mind as I read was: What’s so special about the playwright? I confess during early readings (comedies), the inquirywas offered questioningly, mockingly. But the more I read, the more I began to see that he was at least just a little above average. So why so special?

Was it his plots? I suspect not, because one of his great talents was thievery. He lifted plots and stories from old and ancient sources and even contemporary plays to shape them to his own purposes and audiences’ tastes. He was like a one-man car theft ring and something like a chop shop. He’d take them, dismantle the parts and put them together again, adding needed parts, embellishments and a new body color and sheen. It was no longer the same play and was safe from any former owner claim.

Was it the big questions and issues he dealt with? He’s not the only one who has captured and challenged ambition, lust, deceit, prejudice; so it can’t be merely the issues he raised. The breadth and the quantity of his work, however, is exceptional and testifies of his hard and rapidly working, productive genius.

Was it his language? Absolutely! He knew how to turn a phrase, and we’ve been borrowing them ever since.

Shakespeare’s funerary monument looks down on the poet’s grave in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon.

We often like to think of ourselves as superior to those who came before, but broad, contemporary public support of the Bards plays in his day suggest just the reverse. Shakespeare’s plays entertained diverse audiences, including “groundlings” who would stand for hours to watch them. Among the groundlings were young men—often trade apprentices—out for an afternoon of entertainment. It’s hard for me to imagine a Shakespeare play as a broadly anticipated leisure activity today. What did they have that we don’t?

Another interest I have is the Civil War—not that one; the one in the colonies. I tweet on both the Civil War and Shakespeare, and a twitter follower and friend recently asked me: Why two such diverse interests? I shrugged off the question at the time, but I thought about it for several days before realizing that if I’d been as sharp as Shakespeare, I would have responded in perfectly crafted iambic pentameter that both poet and conflict run so deeply in who we are that to ignore them is to not understand the West, the US and ourselves—what we inherited, what we’ve won, what we’ve lost, what we’re even now letting slip away.

Maybe 450 years after his birth, it’s time to re-emphasize Shakespeare’s plays, his themes, his language, his plots and expose more of him to current and coming generations.

I doubt my wife will notice any improvement in my ability to speak in masterful, metered Elizabethan or Jacobean phrases, but we (she and I) have had fun getting here.

Happy 450th, Will! And thanks for letting me sit beside thee.

The post Sitting by a Dead Man appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

April 5, 2014

Midwest Book Review Gives Us “A River Divides” Review

A River Divides Review from Midwest Book Review:

A River Divides Review from Midwest Book Review:

Midwest Book Review is a premier reviewer of independent and small press books and has included an A River Divides review in its April 2014 issue of Reviewer’s Book Watch. The reviewer was Michael J. Carson.

Here it is:

A River Divides

Michael J. Roueche

Vesta House Publishing

9780983756767 $17.99 www.VestaHousePublishing.com

2012 Cooke Fiction Award-winning author Michael J. Roueche presents A River Divides, book two in the Beyond the Wood series. Set in 1864, during the last throes of the American Civil War, the story follows Confederate widow Betsy Henderson, and runaway slave William searching for freedom and the opportunity to fight for the Union. A complex narrative about conflicted individuals struggling to be true to themselves and their beliefs, despite the harsh realities surrounding their lives, A River Divides is a sober, thoughtful, and expertly researched Civil War novel. Highly recommended.

Thanks to Mr. Carson and Midwest Book Review Editor-in-Chief James A. Cox. Midwest fills an important space in book reviews with integrity, and they’ve been doing it since the ’70s.

If you’re interested, check out the link: A River Divides review at Midwest Book Review.

The post Midwest Book Review Gives Us “A River Divides” Review appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

February 17, 2014

Othello: Wholesale Destruction by an “Honest” Man

Desdemona’s father often invites Othello to visit, where the general recounts his life, thus winning Desdemona’s heart. (“Othello Recounting his Adventures to Desdemona” by Robert Alexander Hillingford) (in Public Domain).

Othello, the Moor of Venice, is a great and deeply disturbing play, and I credit Shakespeare for challenging his audiences’ rising racial biases in the play.

In saying that it’s important to note the play predates the racism that develops in following centuries, based on single-race slavery. Shakespeare wrote Othello in 1603, four years before the founding of Jamestown (Virginia) and nearly 20 years before the first indentured African servants were imported to the colony. However, that black Africans were perceived as outsiders or “others” even before the play can be seen by the language used by Queen Elizabeth in her effort to deport several “blackmoors”: “Of late divers blackmoores brought into this realm, of which kind of people there are already here to manie…. Those kinde of people should be sente forth of the land.” (See Emily C. Bartel’s article ”Too Many Blackamoors: Deportation, Discrimination, and Elizabeth I” (SEL: Studies in English Literature, 2006)

Othello, the man as Shakespeare presents him, is noble; an intelligent military leader and hero. He is also a Moor.

What is a Moor? Good question: As Kate Lowe (professor of Renaissance History and Culture, and Co-director of the Centre for Renaissance and Early Modern Studies, Queen Mary University of London) proclaims on the British Museum and BBC radio program Shakespeare’s Restless World:

The word Moor sounds impressive, but it actually signifies very little. Originally it was the classical word that came from somebody who lived in Mauritania, the Roman province across the top of North Africa. After that it gained other meanings, one of which was black. It also then gained the meaning of a Muslim, but when it is used in Elizabethan England it is just imprecise.

It’s clear in the play, however, that Othello is a Christian, black African, employed by the city-state of Venice. The general is clearly loyal to and appreciated by Venetian government and society. So important to the state’s safety is he that he is permitted great latitude in his personal and professional activities. But a decision in each, his personal and professional life, sets up the good general for dark, diabolic tragedy.

On the personal front, the young daughter of one of the aristocracy falls in love Othello and encourages his attentions. The middle-aged Moor reciprocates the feelings. They secretly marry, much to the consternation of her father who previously had honored Othello with many invitations to his home (where his daughter and the Moor met and courted).

On the professional front, he chooses for his second in command the faithful Michael Cassio.

Neither decision nor the succeeding act is a problem. But they are doors opening just far enough for the fabulously evil Iago, star of the show, to wiggle his devilish soul through.

The general is clearly brilliant on the field and wholesome in his interpersonal relationships, but Iago is the genius of the story. Officially and reputedly he is Othello’s faithful, loyal ancient (a flag bearer or ensign), but within his soul—which he willing describes to us throughout the play—he lusts for Othello’s virtuous new wife, Desdemona; envy’s the Moor’s professional success; is jealous and angry that Othello has not chosen him as his lieutenant, giving that honor instead to Michael Cassio. For these, and various other reasons he describes to us, he hates Othello.

Iago’s brilliance is in his ability to accurately perceive the inner-motives and weaknesses of people around him. Glorying in his evilness, he then offers each the temptations and suggestions that send them tumbling toward destruction.

Reading Othello is like examining the hub and spokes of a wheel. “Honest” Iago is hub, and he delivers his specially selected poison for and along each spoke individually.

To the hated Moor, he subtly but increasingly with time and “proof” creates doubt of Desdemona’s virtue, leveraging the “green-eyed” monster of jealously to the Moor’s final death. (It looks to these 21st Century eyes that Shakespeare allows Iago, the fiend of the play, to vent his society’s rising disdain for black Africans.)

At the same time, to Desdemona, Iago acts the kind, wise friend, counseling how to deal with the Moor, pretending that he himself were not the very devil working against her.

To Michael Cassio, to whom honor is paramount, Iago plots to destroy Cassio’s honor and tear him from the love of the Moor.

To Roderigo, a man who craves Desdemona, he offers empty promises that he’ll have her, if he’ll just be patient a bit longer.

Iago even uses his eager-to-please and shifting-morals wife, Emilia, faithful servant to Desdemona, to unwittingly betray her mistress.

But there, in his most intimate betrayal he finally is unmasked. It is Emilia who finally discovers and reveals what he is. Unwittingly, she captures it even before she knows the guilty party is her husband: “I will be hanged if some eternal villain, some busy and insinuating rogue, some cogging, cozening slave, to get some office, have not devis’d this slander….”

Othello grieves Desdemona’s death. (“The Death of Desdemona” by Eugene Delacroix, 1858. In Public Domain.)

But she discovers it minutes too late. Othello has killed Desdemona because he has “seen” proof that she has cuckold him with Cassio. He kills himself when he realizes the deception.

Foolish Roderigo is first impoverished and then murdered, Cassio left crippled, and Emilia is slain by her conniving husband.

Crucial to the success of his many conspiracies is Iago’s reputation. He must be seen as thoroughly honest. Evidence of that reputation is overwhelming, with Othello–or Michael Cassio—proclaiming Iago honest at least 16 times. Such phrases as “a man he is of honest and trust;” “Iago is most honest;” “I never knew a Florentine more kind and honest;” “this honest creature.”

And Iago is quick to add to his image of honesty, proclaiming (ironically) “as honest as I am;” “as I am an honest man;” “I protest, in the sincerity of love and honest kindness; “this advice is free I give and honest.”

Iago is honest only with the audience throughout the play. He tells us his thoughts and shows his obsession with destroying Othello and everyone who is dear to the general. Only when Iago has succeeded, been found out and sentenced to torture and death, does he clam up. No longer are we his confidants, and we’re left wondering what in the end he thinks and feels.

The dark-skinned Othello has a soul of light, deceived into murder. The light-skinned Iago has a soul of darkness. The light-skinned Desdemona has a soul of light, but Iago paints it black. Shakespeare allows Iago to sit in the cesspool of racism, but he portrays Othello as an honorable soul, challenging his 1603 audience and–perhaps even more so–audiences today.

Othello warns of selfishness, lust, ambition, but mostly of jealousy and the power of suggestion and insinuation. In Macbeth, you wonder about the intent of the “weird sisters” and their prophecies: Are they merely recounting the future or trying to influence Macbeth. In Othello, there’s no doubt that Iago is trying to crush Othello.

Othello, the Moor of Venice, earns five bards:

Quotes I liked:

Iago: In following him, I follow but myself; heaven is my judge, not I for love and duty, but seeming so, for my peculiar end: For when my outward action doth demonstrate the native act and figure of my heart in compliment extern, ’tis not long after but I will wear my heart upon my sleeve for daws to peck at: I am not what I am.

Brabantio: He bears both the sentence and the sorrow that, to pay grief, must of poor patience borrow.

Duke: To mourn a mischief that is past and gone is the next way to draw new mischief on.

Iago: Our bodies are our gardens, to the which our wills are gardeners: so that if we will plant nettles, or sow lettuce, set hyssop and weed up thyme, supply it with one gender of herbs, or distract it with many, either to have it sterile with idleness, or manured with industry, why, the power and corrigible authority of this lies in our wills. If the balance of our lives had not one scale of reason to poise another of sensuality, the blood and baseness of our natures would conduct us to most preposterous conclusions: but we have reason to cool our raging motions, our carnal stings, our unbitted lusts

Iago: It is merely a lust of the blood and a permission of the will.

Iago: Knavery’s plain face is never seen till us’d.

Cassio: O God, that men should put an enemy in their mouths to steal away their brains! That we should, with joy, pleasance revel and applause, transform ourselves into beasts!

Iago: When devils will their blackest sins put on, they do suggest at first with heavenly shows

Iago: How poor are they that have not patience! What wound did ever heal but by degrees? Thou know’st we work by wit, and not by witchcraft; and wit depends on dilatory time.

Iago: O, beware, my lord, of jealousy; It is the green-eyed monster which doth mock the meat it feeds on

Iago: The Moor already changes with my poison: Dangerous conceits are, in their natures, poisons. Which at the first are scarce found to distaste, but with a little act upon the blood, burn like the mines of Sulphur.

Emilia: But jealous souls will not be answer’d so; they are not ever jealous for the cause, but jealous for they are jealous: ’tis a monster begot upon itself, born on itself.

Roderigo: Your words and performances are no kin together.

Emilia: Thou hast not half that power to do me harm as I have to be hurt.

Othello: Then must you speak of one that loved not wisely but too well; of one not easily jealous, but being wrought perplex’d in the extreme; of one whose hand, like the base Judean (“Judean” in first folio; “Indian” in some), threw a pearl away richer than all his tribe

Next Up: I’m finished with all of Shakespeare! But I will be writing about my impressions after reading all the plays (and poems).

The post Othello: Wholesale Destruction by an “Honest” Man appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

February 12, 2014

Shakespeare’s Restless World: A Book Worth Reading

Shakespeare’s Restless World: A Portrait of an Era in Twenty Objects by Neil MacGregor

Shakespeare’s Restless World: A Portrait of an Era in Twenty Objects by Neil MacGregor

I just finished reading and blogging all of Shakespeare’s plays (to celebrate the Bard’s 450th birthday)–haven’t yet posted the Othello blog, so I was intrigued when I heard Diane Rehm’s (NPR) interesting interview of Mr. MacGregor, director of the British Museum, about his Shakespeare’s Restless World. I read the book based on that interview.

Shakespeare’s Restless World greatly enhanced my understanding of the social context of the late 1500s/early 1600s in which Shakespeare wrote, e.g., from the impact the Plague had on the theater (and Romeo and Juliet) to the seemingly over the top bloody acts portrayed in several tragedies and histories.

The Elizabethan and Jacobean world surrounding Shakespeare and his audience was changing rapidly (like our own), and that is a key takeaway from Shakespeare’s Restless World.

The book, perhaps because it’s source is radio interviews, is an easy, quick read; chapters short; photos and illustrations are outstanding. The use of objects to symbolize the social circumstances helps memory.

This is a great read for anyone interested in that crucial time in history or in Shakespeare or who is reading or intends to read any of his plays.

The book follows the success of Neil MacGregor’s earlier British Museum undertaking A History of the World in 100 objects.

The post Shakespeare’s Restless World: A Book Worth Reading appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

January 27, 2014

Hamlet: Questions of Morality and Mortality

Pedro Amẻrico‘s Visão de Hamlet (Hamlet’s Vision) mixes the early appearance of the ghost of Hamlet’s father with the later-in-the-play use of Yorick’s skull. [In Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons]

Hamlet excels all the other Shakespeare works I’ve read—that’s my take on it, with only Othello left to visit. It probably could have been a little shorter, at times more to the point—after all, “bevity is the soul of wit,” but its messages, intrigue, bad guy and plot have so much in them that you can’t help but come away moved and maybe a bit changed.

The story is of the complete annihilation of two families, Hamlet’s and his girlfriend’s. Under different circumstances, the couple surely would have lived long, happy, fulfilling lives as king and queen of Denmark, other than the odd battle with Norway’s aspiring Fortinbras. But they were unfortunate to be born at a time of ambition, jealousy and murder. (Wait! That’s constant in human history.)

Hamlet Plot

The plot is simple. Hamlet’s father, also named Hamlet, is murdered by his own brother who aspires to the throne and the bed of his brother’s queen. He seizes both quickly (too quickly the queen, in Hamlet’s eyes). Hamlet suspects foul play, and his suspicions are borne out by the appearance of an apparition that appears to the prince and associates. The ghost recounts a story of “murder most foul,” his own murder at the deceptive, grasping hands of the new king. The ghost (the former king), was struck down before he had a chance to repent and is left for a time to wander the earth in the night, while suffering hellish agony during daylight hours. (Contrast Hamlet’s refusal later to kill the king while his stepfather prays for fear he is repenting at that very moment and thus would be eligible for Heaven. The murdering uncle had no compassion on the older Hamlet.) The ghost’s command to Hamlet: Revenge! Kill the usurping king.

Hamlet attends the play he dubs “The Mousetrap” to flush out his stepfather’s guilt. [In Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons]

Hamlet affects madness to test the “good” ghost’s information and to position himself for the vengeful blow. The test takes the form of a play, “The Death of Gonzago,” which Hamlet wants presented by a visiting troupe of players. He asks that in the altered play, they mimic the way his father was slain–poison in the ear while sleeping. If the new king flinches in guilt, Hamlet will know the ghost has told the truth. During the play, which Hamlet calls “The Mousetrap,” the king is visibly touched to the quick. Hamlet is sure.

At the same time, king and queen worry about Hamlet’s moodiness and wonder its cause. The queen, who seems excessively attached to Hamlet, thinks the problem is the death of his father and her sudden remarriage to Hamlet’s uncle. A verbose, busybody—but oddly at times in the play wise—minister is sure Hamlet’s agitation is due to instructions he has given his fair daughter, Ophelia, who is romantically attached to the prince. He told her she should give Hamlet no attention, because he was out of her league. Her shunning Hamlet is obviously, according to minister Polonius, the cause of his madness. He and the king determine to test this hypothesis, by setting up, then watching interaction between the young couple. (People spying on other people is an intentional, necessary constant in the play.) Alas, after watching Hamlet’s feigned nonsense, it’s clear Hamlet’s course of lunacy is not created by the loss of the love of the maiden.

Hamlet is not well suited or quick to revenge, struggling with his assignment. At one point, he comes upon the king in prayer. But he convinces himself it wasn’t the right time and place. His father has to haunt him again to steel him for the bloodletting.

Away to England with Hamlet, commands the King, with intentions to have the prince murdered on the island. But first, another test. Polonius will hide in the queen’s closet (a small office, although mostly played as the queen’s bedroom now) while the queen seeks the truth from Hamlet. Polonius hides behind a tapestry. In Polonius’s hearing, Hamlet gives a tongue lashing to his mother so heavy that the queen cries for help. The good minister responds with noise from his hiding spot. In an instant, Hamlet is upon him, stabbing him through the covering. Alas, Hamlet is disappointed to find he has not killed an eavesdropping king. Polonius’s body idles on the floor, while Hamlet finishes turning a mirror on his mother’s inner self.

Actor John Philip Kemble portrays Hamlet, holding Yorick’s skull, as the Dane considers that this is the very skull–when it had skin upon it–a young Hamlet had kissed. A macabre related fact is Polish pianist André Tchaikowsky posthumously donated his own skull to the Royal Shakespeare Company for use in Hamlet. His skull was used in its most recent production. [In the public domain via Wikimedia Commons]

Hamlet is sent to England for his execution, but he turns the conspiracy on its members, and the king’s messengers and Hamlet’s former friends “Dear Rosencrantz” and “gentle Guildenstern” are put to death by the English instead. In the meantime, his true love Ophelia has become mad because of her father’s death and killed herself in her insanity. (Interesting contrast that Hamlet feigns craziness because of the death of his father and broods over thoughts of suicide, while poor Ophelia’s sanity has been truly destroyed by the death of her father, and in her madness, she breaks the strictly obeyed at the time commandment against taking one’s own life.)

Laertes, Polonius’s son and Ophelia’s brother, away in France, returns to avenge his father’s murder. The king now conspires with Laertes: The king will wager on Hamlet being above to withstand the fierce fencing skills of Laertes as a cover for a double-sure plot to kill the prince. Laertes will use an unblunted rapier to scratch Hamlet, while “anointing” its tip with poison to ensure the prince’s death. The king will also offer, during the match, a poisoned drink to the prince.

Hamlet doesn’t feel right about the challenge, but rejects his instinct as “augury.” The two young men fight. Hamlet gets the better of Laertes because the prince has been practicing a lot while Laertes was in France. The king, then the queen, offer Hamlet a drink because of his exertions. But Hamlet declines—he’ll drink it later. The queen drinks to her son, unbeknownst to her that it is a “poisoned cup,” even though her current husband orders her not to drink it. She collapses during the final part of the fight, while Laertes frustrated that he cannot strike Hamlet cheats to scratch him with the poisoned rapier. Hamlet responds in anger and in the pursuing scuffle, Hamlet ends up with Laertes’s sword and penetrates his opponents skin with its still-envenomed edged. Thus Laertes, the queen and Hamlet are dying in unison. The king suggests the queen collapsed because of combatant blood. But the queen realizes it is the drink, then dies. Laertes confesses the king is the font of the conspiracy, then dies. Hamlet kills the king, then dies. Two families gone, attributable to the overreaching ambition and lust of Hamlet’s uncle. Denmark would have been left monarch-less, but for the arrival of Fortinbras of Norway who’s willing to take on the kingdom.

Mortality and Morality

The play raises questions of mortality and morality. “To be or not to be.” Is life worth it when there is so much tribulation, and what is the right thing to do? Revenge? In this case, righteous indignation, filial loyalty and revenge heap death on the royal family.

The main source for Hamlet is a twelfth century manuscript of Historia Danica by Saxo Grammaticus, printed in 1514, but probably captured by Shakespeare in the French Histoires Tragiques of Francois de Belleforest.

My earliest experience with Hamlet was when I was a young child. I, apparently frightened of the dark and everything that might go on when my eyes were closed, asked my father if one could be killed while praying. My father tried to divert my fears by telling me that Hamlet came upon Claudius (the king) while he was praying and couldn’t bring himself to kill him. At the time, I didn’t know who Hamlet was or why he would kill anyone. I assumed Hamlet was the bad guy. I took enough comfort from the story to continue praying with my eyes closed, but I wondered for years who were these men my father referenced.

There are several outstanding movie productions of the play:

1) Ken Branagh’s Oscar-nominated, four-hour production. It presents Denmark as less dreary than some of the other productions.

2) Currently available for free streaming at PBS Great Performances is the Royal Shakespeare Company’s more modern take on Hamlet. I believe it’s three hours long.

3) I was pleasantly surprised by Franco Zeffirelli’s abridged version. Some parts and lines are shifted within the plot, but it only requires a couple of hours to watch it. My surprise focused on Mel Gibson as Hamlet. I thought he did a fine job.

The downsides to revenge, ambition, lust, conspiracy are my takeaways from Hamlet. All four attributes return to the heads that conjured them.

Five bards to Hamlet, perhaps the best of Shakespeare:

Quotes I like:

Hamlet: How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable seem to me all the uses of this world!

Hamlet: He was a man, take him for all in all, I shall not look upon his like again.

Ophelia: Do not, as some ungracious pastors do, show me the steep and thorny way to heaven; whiles, like a puff’d and reckless libertine, himself the primrose path of dalliance treads, and recks not his own rede.

Polonius: And these few precepts in thy memory see thou character. Give thy thoughts no tongue, nor any unproportioned thought his act. Be thou familiar, but by no means vulgar. Those friends thou hast, and their adoption tried, grapple them to thy soul with hoops of steel; but do not dull thy palm with entertainment of each new-hatch’d, unfledged comrade. Beware of entrance to a quarrel, but being in, bear’t that the opposed may beware of thee. Give every man thy ear, but few thy voice; take each man’s censure, but reserve thy judgment. Costly thy habit as thy purse can buy, but not express’d in fancy; rich, not gaudy; for the apparel oft proclaims the man, and they in France of the best rank and station are of a most select and generous chief in that. Neither a borrower nor a lender be; for loan oft loses both itself and friend, and borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry. This above all: to thine own self be true, and it must follow, as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to any man.

Marcellus: Something is rotten in the state of Denmark.

Hamlet: There are more things in heaven and earth, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

Hamlet: The time is out of joint:—O cursed spite, that ever I was born to set it right!

Polonius: It is common for the younger sort to lack discretion.

Polonius: Brevity is the soul of wit.

Queen: More matter and less art.

Hamlet: To be honest, as this world goes, is to be one man picked out of ten thousand.

Hamlet: You yourself, sir, should be old as I am, if, like a crab, you could go backward.

Hamlet: These is nothing either good or bad, but thinking it makes it so

Hamlet: Use every man after his desert, and who should scape whipping?

Hamlet: Murder though it have no tongue, will speak with most miraculous organ.

Polonius: With devotion’s and pious action we do sugar o’er the devil himself.

Hamlet: To be, or not to be: that is the question: Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, or to take arms against a sea of troubles, and by opposing end them? To die: to sleep; no more; and by a sleep to say we end the heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to, ’tis a consummation devoutly to be wish’d. To die, to sleep; to sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there’s the rub; for in that sleep of death what dreams may come when we have shuffled off this mortal coil, must give us pause: there’s the respect that makes calamity of so long life; for who would bear the whips and scorns of time, the oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely, the pangs of despised love, the law’s delay, the insolence of office and the spurns that patient merit of the unworthy takes, when he himself might his quietus make with a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear, to grunt and sweat under a weary life, but that the dread of something after death, the undiscover’d country from whose bourn no traveller returns, puzzles the will and makes us rather bear those ills we have than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all; and thus the native hue of resolution is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought, and enterprises of great pith and moment with this regard their currents turn awry, and lose the name of action.

Ophelia: To the noble mind rich gifts wax poor when givers prove unkind.

Ophelia: Could beauty, my lord, have better commerce than with honesty?

Hamlet: What should such fellows as I do crawling between heaven and earth? We are arrant knaves, all; believe none of us. Go thy ways to a nunnery.

Hamlet: Suit the action to the word, the word to the action

Queen: The lady protests too much, methinks.

King: What do you call the play? Hamlet: The mouse-trap.

King: What’s in prayer but this two-fold force, to be forestalled ere we come to fall, or pardon’d being down? Then I’ll look up; my fault is past. But, O, what form of prayer can serve my turn? ‘Forgive me my foul murder’? That cannot be; since I am still possess’d of those effects for which I did the murder, my crown, mine own ambition and my queen. May one be pardon’d and retain the offence? In the corrupted currents of this world offence’s gilded hand may shove by justice, and oft ’tis seen the wicked prize itself buys out the law: but ’tis not so above; there is no shuffling, there the action lies in his true nature; and we ourselves compell’d, even to the teeth and forehead of our faults, to give in evidence. What then? What rests? Try what repentance can: what can it not? Yet what can it when one can not repent? O wretched state! O bosom black as death! O limed soul, that, struggling to be free, art more engaged! Help, angels! Make assay! Bow, stubborn knees; and, heart with strings of steel, be soft as sinews of the newborn babe!

King: My words fly up, my thoughts remain below; words without thoughts never to heaven go.

Hamlet: A man may fish with the worm that hath eat of a king, and eat of the fish that hath fed of that worm.

Hamlet: What is a man, if his chief good and market of his time be but to sleep and feed? A beast, no more. Sure, he that made us with such large discourse, looking before and after, gave us not that capability and god-like reason to fust in us unused. Now, whether it be bestial oblivion, or some craven scruple of thinking too precisely on the event, a thought which, quarter’d, hath but one part wisdom and ever three parts coward, I do not know why yet I live to say ‘This thing’s to do;’ sith I have cause and will and strength and means to do’t. Examples gross as earth exhort me: Witness this army of such mass and charge led by a delicate and tender prince, whose spirit with divine ambition puff’d makes mouths at the invisible event, exposing what is mortal and unsure to all that fortune, death and danger dare, even for an egg-shell. Rightly to be great is not to stir without great argument, but greatly to find quarrel in a straw when honour’s at the stake. How stand I then, that have a father kill’d, a mother stain’d, excitements of my reason and my blood, and let all sleep? while, to my shame, I see the imminent death of twenty thousand men, that, for a fantasy and trick of fame, go to their graves like beds, fight for a plot whereon the numbers cannot try the cause, which is not tomb enough and continent to hide the slain? O, from this time forth, my thoughts be bloody, or be nothing worth!

Queen: So full of artless jealousy is guilt, it spills itself in feating to be spilt.

Ophelia: We know what we are, but know not what we may be.

King: When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalias!

Horatio: If your mind dislike anything, obey it

Hamlet: There’s a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, ’tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come: the readiness is all

The post Hamlet: Questions of Morality and Mortality appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

January 8, 2014

Macbeth: A Fall Without Redemption

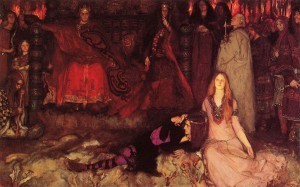

The three “weird sisters” meet and tempt returning heroes Macbeth and Banquo.

As I watched and read Macbeth, I couldn’t help but think of Dostoevsky‘s Crime and Punishment. Both Macbeth and the novel’s main character, Raskolnikov, delve into murder and darkness. But there are core and defining differences.

Macbeth is a play about a man who at every choice, encouraged by his wife, chooses the evil path, gives in to temptation, and seems in the end to give himself completely to darkness. The evil he chooses along the way, he would never have chosen in the beginning. Virtuous emotions felt (love for his wife) in the beginning, by the end of his journey downward, are as feeble as the evil that controls him is vibrant, destructive. He has traveled the clichéd slippery slope.

Macbeth–enticed and bullied on by his own apparently unquenchable ambition, the three “weird sisters” prophecy that he’d be king and his beloved Lady Macbeth’s (that totals four witches) insistence that he act to fulfill the prophesy–dips at first hesitantly into murder for wealth and power. Before he lowers himself into the bloody gore, he seems to have a conscience and hesitates to do the deed. His Lady sees his humanity and frets that he’ll not have the will to take the kingdom by force (i.e., murder): “I fear thy nature; It is too full o’ the milk of human kindness to catch the nearest way.”

Whatever sensitivities he begins with, he loses incrementally in murdering the good King Duncan, ordering the murder of Banquo and his son (Banquo’s son survives perhaps only because in the Shakespeare’s day, it was erroneously believed that King James, new to the English throne, was a descendant of Banquo), and the slaughter of Macduff’s family—all his “pretty ones” and “their dam.”

Macbeth’s seeking out evil leads to his hopeless despair, in which he cannot even, it seems, grieve for his Lady in her suicide. His body is alive, but his soul is empty by the time he dies at the hands of one not born of woman.

Celebrated 19th and 20th century British Actress Ellen Terry portrays Lady Macbeth in 1889 painting by John Singer Sargent.

Lady Macbeth—harder than Macbeth in the beginning, able to “unsex” herself—eggs him on; but in the end it is the Lady who breaks down. Unpredictably it is the seemly conscienceless Lady Macbeth who dies a victim of internal grief of guilt, while the more timid, thoughtful Macbeth leads a desperate fight to survive. Hardened Macbeth is unwilling to kill himself as Antony did in Antony and Cleopatra. Their—the Macbeth’s—decisions open both to nightmarish guilt, but instead of confessing and repenting, the guilt festers in both till their destruction.

Macbeth is stark warning that choosing evil a bit at a time is a downward slog to destruction, unless the soul and its decisions change. There is no redirection and thus no redemption for the Macbeths. They become inhuman, creatures of the hell they have sought.

How does this relate to Crime and Punishment? Certainly the men have different motives for their murders. Raskolnikov murders almost as an intellectual exercise, yet suffers the same illness and madness of guilt as the Macbeths. However, Doestoevsky’s protagonist is not the Macbeths, and Raskolnikov is salvaged by a Christ-believing, but desperate prostitute. Raskolnikov confesses, his heart softening till he is able to repent. He is redeemed and experiences happiness as a new creature (albeit in Siberia).

I suspect that Macbeth gets to the point where his conscience has been destroyed, and he can no longer (or will not) repent, having given himself completely to his “o’erleaping” ambition, and even the witches proclaim him “something evil.” He has become, if it’s possible, beyond redemption.

Source for Macbeth was Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland.

Macbeth is a great play, perhaps the one I’ve enjoyed most to date, with its caution against choosing evil for unfettered ambition and the power of suggestion.

I give Macbeth five Bards:

Quotes I like:

Banquo: What, can the devil speak true? …Oftentimes to win us to our harm, the instruments of darkness tell us truths; win us with honest trifles, to betray’s in deepest consequence.

Macbeth: Why do I yield to that suggestion whose horrid image doth unfix my hair, and make my seated heart knock at my ribs, against the use of nature?

Macbeth: Come what come may, time and the hour runs through the roughest day.

Malcolm: Nothing in his life became him like the leaving it

Macbeth: Stars, hide your fires! Let not light see my black and deep desires: the eye wink at the hand! Yet let that be, which the eye fears, when it is done, to see.

Lady Macbeth: Yet do I fear thy nature; It is too full o’ the milk of human kindness to catch the nearest way: thou wouldst be great; art not without ambition; but without the illness should attend it.

Lady Macbeth: Come, you spirits that tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here; and fill me, from the crown to the toe, topfull of direst cruelty! Make thick my blood, stop up the access and passage to remorse, that no compunctious visitings of nature shake my fell purpose, nor keep peace between the effect and it! Come to my woman’s breasts, and take my milk for gall, you murdering ministers

Macbeth: The be-all and the end-all

Lady Macbeth: Art thou afeard to be the same in thine own act and valour as thou art in desire? Wouldst thou have that which thou esteem’st the ornament of life, and live a coward in thine own esteem, letting ‘I dare not’ wait upon ‘I would’

Macbeth: False face must hide what the false heart doth know.

Lady Macbeth: These deeds must not be thought after these ways; so, it will make us mad.

Lady Macbeth: A little water clears us of this deed: How easy is it then!

Macbeth: To know my deed, ’twere best not to know myself.

Macduff: Confusion now hath made his masterpiece!

Macbeth: (feigning innocence when Duncan’s death is discovered): Had I but died an hour before this chance, I had lived a blessed time; for, from this instant, there’s nothing serious in mortality: All is but toys: renown and grace is dead; the wine of life is drawn, and the mere lees is left this vault to brag of.

Macbeth: He hath a wisdom that doth guide his valour to act in safety.

Macbeth: Ay, in the catalogue ye go for men; as hounds and greyhounds, mongrels, spaniels, curs, shoughs, water-rugs and demi-wolves, are clept all by the name of dogs: the valued file distinguishes the swift, the slow, the subtle, the housekeeper, the hunter, every one according to the gift which bounteous nature hath in him closed; whereby he does receive particular addition, from the bill that writes them all alike: and so of men.

Lady Macbeth: Things without all remedy should be without regard: what’s done is done.

Hecate: A wayward son, spiteful and wrathful; who, as others do, loves for his own ends

Witches: Double, Double toil and trouble

Witches: By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes

Lady Macbeth: When our actions do not, our fears do make us traitors.

Lady Macduff: I have done no harm. But I remember now I am in this earthly world; where to do harm is often laudable; to do good, sometime accounted dangerous folly

Malcolm: My more-having would be as a sauce to make me hunger more

Lady Macbeth: Out, damned spot! out, I say!–One: two: why, then, ’tis time to do’t.–Hell is murky!–Fie, my lord, fie! a soldier, and afeard? What need we fear who knows it, when none can call our power to account?–Yet who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him. …What, will these hands ne’er be clean?

Angus: Now does he feel his secret murders sticking on his hands; now minutely revolts upbraid his faith-breach; those he commands move only in command, nothing in love: now does he feel his title hang loose about him, like a giant’s robe upon a dwarfish thief. Menteith: Who then shall blame his pester’d senses to recoil and start, when all that is within him does condemn itself for being there?

Macbeth: That which should accompany old age, as honour, love, obedience, troops of friends, I must not look to have; but, in their stead, curses, not loud but deep, mouth-honour, breath, which the poor heart would fain deny, and dare not.

Macbeth: Cure her of that. Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased, pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow, raze out the written troubles of the brain and with some sweet oblivious antidote cleanse the stuff’d bosom of that perilous stuff which weighs upon the heart? Doctor: Therein the patient must minister to himself.

Macbeth: To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow, creeps in this petty pace from day to day to the last syllable of recorded time, and all our yesterdays have lighted fools the way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle! Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more: it is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Next Up: Hamlet

The post Macbeth: A Fall Without Redemption appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

December 23, 2013

Civil War Christmas Remembered

I’ve gathered a panel of experts to answer a few Civil War Christmas questions and to give us a taste of what Christmas was like during the conflagration. The eminent panelists include:

South Carolinian Mary Boykin Chesnut. Her extensive diary actually has little to say about Christmas, perhaps because she never had children.

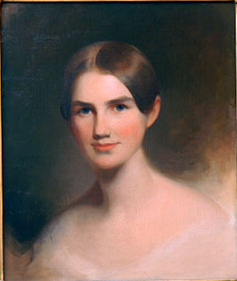

Marylander Elizabeth Blair Lee, daughter of powerful Francis Preston Blair and wife to Samuel Philip Lee—a Lee who served in the Union Navy throughout the war, leaving him far from home during the war. Their son Francis Preston Blair Lee, later a senator, was four when the war broke out, so she gives insight into the Christmas experience of children during the war. Her testimony comes from her correspondence with her husband throughout the war.

Elizabeth Blair Lee kept up correspondence with her ship-bound husband during the war.

Author Margaret Leech who wrote Pulitzer Prize-winning Reveille in Washington, an account of the Civil War in Washington, DC.

Virginian Cornelia Peake McDonald, whose testimony comes from a journal she kept of her family’s life during the war. She gives a Confederate perspective from the Shenandoah Valley, specifically in 1862 when Union forces came through her town of Winchester. She had several young children at the time.

Union political cartoonist Thomas Nast who captured Christmas during the war in several cartoons and helped create the modern American Santa Claus.

Were Civil War Christmases commercial? Tell us about the gifts?

Ms. Lee in 1860

I can feel thankful for all the mercies of God on this day of rejoicing—Tho I so miss you aching to share with me the exuberance of Blair in Xmas gifts & joys . . . [Note the use of Xmas, often erroneously thought of as a modern attempt to remove “Christ” from Christmas.]

I must go to the city to morrow for Christmas gifts—for Blair & the other children—I do hope you will get back here to spend Christmas with your boy & your affectionate Lizzie . . .

Decr 24—I went to finish my Christmas gifts up & to my amaze found invitations for Father Mother You & I—to dine at the White House . . . but I’ll confess myself a lonesome sad woman this even when fixing out my boy’s Christmas pleasure—so many of my joys in him are lonesome—but he is getting stronger & better daily & you were well when I last heard—so I must & ought to be thankful . . . .

Ms. Lee in 1861

I hear that the Donkey is forwarded by Mrs. Alexander as she could do so for thirteen dollars & that is scarcely more than it would cost to take care of it for six months—I would rejoice to have it by Xmas—but Blair is content without it . . .

Ms. Lee in 1862

I have a steam engine which I am going to give him [Blair] from you for Xmas—it winds up & runs about the floor…I always make it joyous today to the little fellow consequently he is full of bright anticipation . . .

Mary Blair has given him a pair of parlor skates which will enchant him & be great exercise on the large porch in bad weather—Ill not let him go alone until he has learned to use them well. …I wish our Christmas could be happy together—which is fondly echoed by our loving boy—but he is still joyous & happy.

. . . So far as we can share Blair’s joys this has been a merry Christmas. He was awake before daylight–& had to take a look at his gifts by candle light—it was six—but you know that is not daylight in my room—Of all the toys nothing pleased him as the Engine & railway Cars & Mary Blair skates—he told me—to say to Papa this is the best Christmas yet . . .

Ms. McDonald in 1862

Christmas is but ten days off, the blessed time that used to be so joyous. It shall have something bright and cheery in it for the children. They shall hang up their stockings, poor little things, even if I have to manufacture the things to put in them.

Ms. Lee in 1863

A velocipede (a wooden “pre-bicycle” without pedals)

I got a toy for Blair from you & one from myself & there Ill stop as Ive more debts than money by a great deal . . . I got a wheelbarrow for you . . . I got a velociped for Blair from me . . . .

Ms. Leech wrote of 1863 Washington City

In the windows of the shops, they saw the gaudy and expensive trifles which pleased the capital of a nation at war: marble and china ornaments, cigar cases, slippers and smoking caps, cloak and opera hoods, military and mechanical toys, hobby horses and pearly-toothed dolls that spoke and sang and even walked.

Ms. Lee in 1864

We have had a quiet pleasant Christmas—Blair wishes everyday was Christmas—he is an exuberantly happy chap The toys are very welcome to him in the stormy days of winter for the Rebs carried off his store of toys which Becky & Bernie [Blair's nurses] had hoarded from his birth but they may now be gladdening some little ones in Virginia—I have felt disappointed all this Christmas time—for I had put it in to my heart for a year nearly that you would be here & I never felt so let down & anxious & thus it is we nurse up our fancies but our disappointments will come up with more intense realization on some days more than others…I received a Christmas pin cushion from Marion & her Mother . . . .

How did you decorate for Civil War Christmases?

Ms. Lee in 1862

Blair is very well & merry out gathering laurels—Some of which I will take in to deck St John’s tomorrow for Christmas. Blair is busy putting some around Papa’s picture—He & Becky will I expect deck all my pictures . . . .

Ms. Leech wrote of Washington City 1862

Mrs. Caleb B. Smith, a truly philanthropic lady, took charge of organizing the Christmas dinners for the soldiers in the hospitals. Evergreens hung in the wards, and a long train of ambulances and wagons was loaded with the provisions donated by Mrs. Lincoln.

Did kids believe in Santa Claus?

Ms. Lee in 1862

I wish you could have seen Blair’s bright face tonight—& heard his odd surmises about Kris Kringle—I have come to the conclusion to cut that thin disguise after this—he asks so many questions that I can only escape story telling by refusing to answer . . .

Ms. Lee a year later

He knows Santa Claus ‘is all story–’ but Papa & Mama are the real Santa Claus

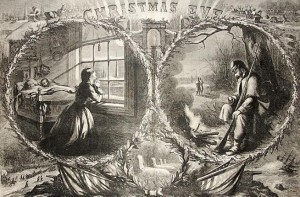

Mr. Nast in 1862 (January 1863 in Harper’s Weekly)

The Thomas Nast illustration in Harper’s Weekly tells a detailed story of a couple separated at Christmas time 1863; a story of love, war-caused hardship, loneliness, prayer, longing, hope, Christmas and Santa Claus. Note the Santa in the upper left—going down a chimney; and upper right—in sleigh with reindeer.]

New York History blog notes: “Nast’s first Santa illustrations, published in the January 3, 1863 edition of Harper’s Weekly, featured Santa visiting dejected Union soldiers.”

New York History blog notes: “Nast’s first Santa illustrations, published in the January 3, 1863 edition of Harper’s Weekly, featured Santa visiting dejected Union soldiers.”

Did people go to Church for Civil War Christmases?

Ms. Lee December 24, 1862

I recd a note from Susan Preston alias Hepburn she wishes to see me, I’ll call—tomorrow when I hope to go to Church.

What was on the Civil War Christmas dinner table?

Lee in 1862

I hope the oysters which he likes will also come for that season.

Chesnut in 1863

James and Mary Chesnut in 1840. (The Granger Collection, NY)

We invited two wounded homeless men who were too ill to come. Alex Haskell, however, who lost an eye, and [Confederate General John Bell] Hood came. . . .Today my dinner was comparatively a simple affair—oysters, ham, turkey, partridges and good wine.

Leech reports of 1863

The markets in Washington had never been so well supplied with grouse, venison, luscious oysters, quail, swan, juicy reedbirds and tender four-dollar turkeys.

What was the atmosphere like during Civil War Christmases?

Leech writes of Washington City, 1862

The burden of gloom and suffering dulled the holiday season. The only diversion was the fire at Ford’s Athenaeum on Tenth Street. Flaming high in a stormy sky, the conflagration illuminated the city. A gentleman claimed that he had read a newspaper on Capitol Hill by the light. …The eggnogs of 1863 [eggnog on New Year's Day] were swallowed with little merriment.

Leech of Washington City, 1863

The [smallpox] scare spread, while the capital celebrated the holidays with eggnogs and feasting, and thronged shops and theatres and parties. People fled in terror from the streetcars at the sign of a mottled complexion.

Ms. McDonald wrote of Winchester, Va. in 1862:

December 24th

In the kitchen all day making cakes for the children’s Christmas, labour by no means light with only a young servant to assist . . . In the afternoon I saw from the door a cavalry regiment ride in and take possession of Mr. Wood’s yard and beautiful ground . . . I beheld two cavalry men on their way through the yard stop and take the Christmas turkey that had been dressed and hung on a low branch of a tree for cooking on the morrow.

He had walked with it a few steps before I realized what had taken place, and with consciousness of the loss came the remembrance of the straits to which I was reduced before that turkey could be obtained; how I had spent six dollars, and sent a man miles on horseback to get it rather than have nothing good and pleasant for our Christmas dinner. With the recollection of all that, came the inspiration to try and recover it, so I flew after him, and in a commanding tone demanded the restoration of my property.

The man laughed derisively and told me I have no right to it, being “Secesh” as he expressed it, and that it was confiscated to the United States. “Very well,” said I, “go on to the camp with it, and I will go with you to the commanding officer.” He gave it up then and I returned triumphantly to the kitchen with it. Just as I got back I looked and saw a regiment of infantry . . . filing into our orchard. In five minutes the garden fence had disappeared and the boarding from the carriage house and other buildings was being torn off. Some were carrying off the wood that my poor little boys had cut and hauled. It made me almost weep to see the labour of their poor little hands appropriated by those thieves. How thankful I was that [the boys] were far away. I permitted them to go their Uncle Fayette’s some days ago to spend the Christmas with his boys.

. . .While I was trying to arrest the work of destruction, someone told me the robbers were in the kitchen, carrying off the things. In I went, and found it full of men. One took up a tray of cakes, and as I turned to rescue them, Mary, the servant, pulled my sleeve to show something else they were carrying off, and when I turned to him another seized something else till I was nearly wild. At last Mary said, “Miss Cornelia he’s got your rusks.” (Those rusks that I had made myself and worked till my wrists ached, the first I ever made.)

A man had opened the stove and taken out the pan of nice light brown rusks, and was running out with them. A fit of heroism seized me and I darted after him, and just as he reached the porch steps, I caught him by the collar of his great coat, and held him tight till the hot pan burnt his hands and he was forced to drop it. An officer was riding by, and beholding the scene stopped and asked the meaning of it. Explaining, I lost my gravity, and so did he, and there we laughed long and loud over it. It was so perfectly ridiculous that I forgot for the time all the havoc that was going on. The officer went away, and soon a guard came and quiet was restored, at least near the house, but all night long the work of demolition of buildings went on.

December 25th

The day has been too restless to enjoy, or even to realize that it was Christmas. All day reports of the advance of the Confederates, and our consequent excitement. Just as we were sitting down to dinner, we heard repeated reports of cannon. We hurried from the table and found the troops all hastily marching off. They expect a fight, I was told by one, as the Confederates were near town. We could eat no more dinner, the girls and myself, so it was carefully put away till we could enjoy it.

Thank you, panelists. Some things continue from Civil War Christmas traditions–toys, shopping, a uniquely American Santa Claus, good food, family, evergreen decorations. Unfortunately, war and conflict and separation from family remain as well.

My hope for you for this Christmas is that you have a great one, no matter your circumstances. And for all, I pray we will someday soon have fellowship and peace of all men and women. In the words of the Civil War Christmas poem of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow:

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

God is not dead, nor doth he sleep

The wrong shall fail, the right prevail

With peace on earth, good will to men

Merry Christmas!

Sources:

Chesnut, Mary (author), Woodward, C. Vann (editor), Mary Chesnut’s Civil War, Yale University Press, July 1983.

Lee, Elizabeth Blair Lee (author), Laas, Virginia Jeans (editor), Wartime Washington: The Civil War Letters of Elizabeth Blair Lee, University of Illinois Press, August 1999.

Leech, Margaret, Reveille in Washington: 1860-1865, Harper & Brothers, January 1941.

McDonald, Cornelia Peake (author), Gwin, Minrose C. (Editor), A Woman’s Civil War: A Diary with Reminiscences of the War, from March 1862, University of Wisconsin Press, April 1992.

The post Civil War Christmas Remembered appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

December 17, 2013

Romeo and Juliet: Wanting to Take Sides

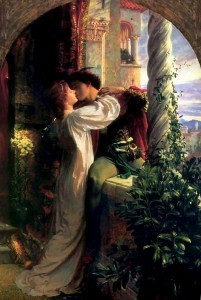

Frank Dicksee captures the young couple’s passion in his 1884 Romeo and Juliet.

I finished Romeo and Juliet and found in it, especially during the couple’s early romance, some of the softest, warmest, most lyrical poetry I’ve seen in Shakespeare. His words are more beautiful than either of the young, beautiful, tragic Romeo and Juliet. In fact, the words make the couple:

“For saints have hands that pilgrims’ hands do touch”

“Soft! What light through yonder window breaks”

“It is not hand, nor foot, nor arm, nor face, nor any other part belonging to a man”

“With love’s light wings did I o’er-perch these walls”

We, as a culture, reference them so oft—because of their beauty—that some are clichéd and mocked, including the play’s title, Romeo and Juliet.

As I’ve read Shakespeare, I have wondered why his plays have endured for more than 400 years and have concluded: it’s the words, and words matter (in poetry, drama, writing, speaking, and everyday life). His plots weren’t original; his moral messages good, but not unique; it was the words and phrases in which he encased plot and message. Romeo and Juliet is a fine example with its eloquent, memorable description and words that are fun to ear and invite repetition.

There is no real suspense in Romeo and Juliet, since the Prologue gives a quick synopsis even before we meet the “star-crossed lovers.” He tells us the play will last two hours (although I suspect it took longer), during which the couple will “take their life”–perhaps the fact that “their life” is in the singular suggests the eventual knitting of their hearts. We also know the families hold “ancient grudge,” and that the grudge is going to burst into “new mutiny.” And finally, we know the end of their young lives will end the “parents’ rage.” So we’re left free to watch the strife, love and tragedy without hope. Yet, don’t we still hope that somehow, this time, the story will be different; that the couple will steal away to Mantua and happiness away from poisoning anger.

I find myself identifying much more strongly with the Montagues than with their enemies. The Montague boys are kind, gentle—Romeo, Benvolio, Balthasar. Whereas the Capulets’ Gregory and Sampson open the play looking for a fight, and Tybalt (this is the kind of guy for which sword-control laws need to be passed in fair Verona) is quick to back them and to raise the threats and bickering to general riot. From the first moments of the play, I like the Montagues and wish the Capulet gang would disappear. And isn’t that the point. The ancient grudge has grown so fierce that it no longer matters who starts an episode, or who is gentle and kind, or who is wrong or right, as long as both sides are willing to jump in the brawl. Gentle Romeo kills in revenge, the Capulets want him killed for murder; and the pattern continues forever in what could easily have become a last man standing feud. (“The 10 Most famous Feuds in History” includes the Grahams vs. Tewksbury feud, which literally ended when only one adult male from either family survived.)

In the midst of fevered anger, it takes courage to be the one who refuses to continue the violence. Romeo, gentle as he was (and he did try), wasn’t big enough to stop it. Mercutio wasn’t even a Montague, but a relative of the Prince. Romeo could have had the power of the law behind him in making sure Tybalt paid for killing Mercutio. It would have been easy. Instead, the Prince loses a couple of relatives, the Capulets and Montagues lose their prime heirs, and Romeo and Juliet waste their lives. Capulets and Montagues and everyone they touch are destroyed–there’s enough poison for them all, no one escapes: “All are punish’d” in Romeo and Juliet.

On another topic, Shakespeare raises only coincidentally the issue of young love: physical attraction, love at first sight, infatuation. Since the romance ends so abruptly in quick, tragic death, Romeo and Juliet’s love is never tested. Their love barely makes it beyond first steps—a less-than-a-week-long romance is easy: easy in the passion of new romance to throw all other concerns aside, almost easy to be willing to sacrifice all. But the bigger questions about love and about Romeo and Juliet are left unanswered: Did they really love each other? Can love endure? What is required to make it last? Would they choose over time to be happy together, or would they choose to drift apart? Would they choose to cherish the other over self, or would daily life lead them to choose self over unity? (Behind all these questions is Romeo’s lovesickness early in the play; but it’s not for Juliet that he pines. Is Romeo fickle, attracted to the next attractive young woman he sees? Or is Juliet really different? We’ll never know.)

If I remember correctly, Romeo and Juliet was the first Shakespeare I saw, and I was thoroughly impressed. Romeo and Juliet’s main source was probably The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Iuliet, a poem written in 1562 by Arthur Brooke.

The head of the Capulet family captures the message of the play, “Poor sacrifices of our enmity.” I suppose anything sacrificed for enmity leaves us a bit poorer.

Romeo and Juliet earns a “blubbering” five bards:

Quotes I liked:

Romeo: Sad hours seem long.

Romeo: She is rich in beauty; only poor, that, when she dies, with beauty dies her store.

Romeo: Teach me how to forget to think.

Chorus: Bewitched by the charm of looks

Romeo: With love’s light wings did I o’er-perch these walls; for stony limits cannot hold love out, and what love can do that dares love attempt

Juliet: I’ll prove more true than those that have more cunning to be strange.

Juliet: O, swear not by the moon, the inconstant moon, that monthly changes in her circled orb, lest that thy love prove likewise variable. …Do not swear at all; or, if thou wilt, swear by thy gracious self, which is the god of my idolatry, and I’ll believe thee.

Juliet: Although I joy in thee, I have no joy of this contract to-night: It is too rash, too unadvised, too sudden; too like the lightning, which doth cease to be ere one can say ‘It lightens.’

Juliet: I wish but for the thing I have: My bounty is as boundless as the sea, my love as deep; the more I give to thee, the more I have, for both are infinite.

Juliet: Good-night, good-night! Parting is such sweet sorrow, that I shall say good night till it be morrow.

Friar Lawrence: Where care lodges sleep will never lie

Friar Lawrence: Young men’s love, then, lies not truly in their hearts, but in their eyes.

Friar Lawrence: Come, young waverer, come, go with me, in one respect I’ll thy assistant be; for this alliance may so happy prove, to turn your households’ rancour to pure love.

Friar Lawrence: Wisely and slow; they stumble that run fast.

Juliet: How art thou out of breath, when thou hast breath to say to me that thou art out of breath?

Prince: Mercy but murders, pardoning those that kill.

Juliet: What must be shall be.

Apothecary: My poverty, but not my will consents.

Romeo: There is thy gold; worse poison to men’s souls, doing more murders in this loathsome world than these poor compounds that thou mayst not sell: I sell thee poison, thou hast sold me none.

Prince: Where be these enemies?—Capulet,—Montague,—see what a scourge is laid upon your hate, that heaven finds means to kill your joys with love!

Prince: For never was a story of more woe than this of Juliet and her Romeo.

Here are a couple long quotes from Romeo and Juliet, left in verse format. They just can’t be left out:

Romeo and Juliet’s First Meeting:

Romeo (to Juliet): If I profane with my unworthiest hand

This holy shrine, the gentle fine is this:

My lips, two blushing pilgrims, ready stand

To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss.

Juliet: Good pilgrim, you do wrong your hand too much,

Which mannerly devotion shows in this;

For saints have hands that pilgrims’ hands do touch,

And palm to palm is holy palmers’ kiss.

Romeo: Have not saints lips, and holy palmers too?

Juliet: Ay, pilgrim, lips that they must use in prayer.

Romeo: O, then, dear saint, let lips do what hands do;

They pray, grant thou, lest faith turn to despair.

Juliet: Saints do not move, though grant for prayers’ sake.

Romeo: Then move not, while my prayer’s effect I take.

Thus from my lips, by yours, my sin is purged.

Juliet: Then have my lips the sin that they have took.

Romeo: Sin from thy lips? O trespass sweetly urged!

Give me my sin again.

Romeo and Juliet Balcony Scene:

(Juliet appears above at a window)

Romeo: But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.

Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon,

Who is already sick and pale with grief,

That thou her maid art far more fair than she:

Be not her maid, since she is envious;

Her vestal livery is but sick and green

And none but fools do wear it; cast it off.

It is my lady, O, it is my love!

O, that she knew she were!

She speaks yet she says nothing: what of that?

Her eye discourses; I will answer it.

I am too bold, ’tis not to me she speaks:

Two of the fairest stars in all the heaven,

Having some business, do entreat her eyes

To twinkle in their spheres till they return.

What if her eyes were there, they in her head?

The brightness of her cheek would shame those stars,

As daylight doth a lamp; her eyes in heaven

Would through the airy region stream so bright

That birds would sing and think it were not night.

See, how she leans her cheek upon her hand!

O, that I were a glove upon that hand,

That I might touch that cheek!

Juliet: Ay me!

Romeo: She speaks:

O, speak again, bright angel! for thou art

As glorious to this night, being o’er my head

As is a winged messenger of heaven

Unto the white-upturned wondering eyes

Of mortals that fall back to gaze on him

When he bestrides the lazy-pacing clouds

And sails upon the bosom of the air.

Juliet: O Romeo, Romeo! wherefore art thou Romeo?

Deny thy father and refuse thy name;

Or, if thou wilt not, be but sworn my love,

And I’ll no longer be a Capulet.

Romeo: [Aside] Shall I hear more, or shall I speak at this?

Juliet: ‘Tis but thy name that is my enemy;

Thou art thyself, though not a Montague.

What’s Montague? it is nor hand, nor foot,

Nor arm, nor face, nor any other part

Belonging to a man. O, be some other name!

What’s in a name? that which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet;

So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call’d,

Retain that dear perfection which he owes

Without that title. Romeo, doff thy name,

And for that name which is no part of thee

Take all myself.

Next Up: MacBeth

The post Romeo and Juliet: Wanting to Take Sides appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

December 4, 2013

King Lear: “A time to keep and a time to cast away”

Even the dog mourns as Cordelia with her husband-to-be, King of France, parts from her two self-centered sisters who have shown generous portions of that “glib and oily art, to speak and purpose not.” She, unlike her deceived father, can pronounce early on to her siblings, “I know what you are.”

As Ecclesiastes (and Pete Seeger and the Byrds in “Turn, Turn, Turn”) reminds us “there is a season to everything.”

For legendary King Lear, if he ever heard of or read Ecclesiastes, he must have missed or misinterpreted the line “a time to keep and a time to cast away.” If he’d understood it, he might not have been in such a hurry to divest himself of his kingdom and thus his power. It would have saved him a storm of trouble and shorted us a great play.

His rush to throw off the responsibilities of his kingdom gave us a play where misery, injustice, vindictiveness slosh about. Fathers and sons and daughters! All the misery stems from the infidelity of daughters and sons (biological and in-law). It would leave us each suspicious of our offspring, but for Lear characters: faithful yet disinherited Cordelia, humiliated and hunted Edgar, and unexpectedly valiant Duke of Albany. This threesome reminds us that though treachery and ingratitude surround us, there are those moral ones (perhaps few?) who will stand to their duties in gratitude.

The small-souled Edmund captures the heart of the play when he proclaims, “I promise you . . . unnaturalness between the child and the parent; death, dearth, dissolutions of ancient amities; divisions in state, menaces and maledictions against king and nobles; needless diffidences, banishment of friends, dissipation of cohorts, nuptial breaches….”

Plot and Subplot