Michael J. Roueche's Blog, page 4

November 26, 2013

The First Thanksgiving: 150 Years Ago by Proclamation

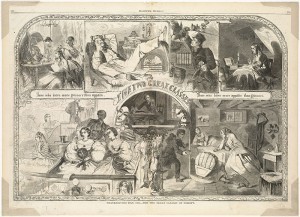

Winslow Homer contrasts the “The two great classes. Those who have more dinners than appetite. Those who have more appetite than dinners” in his 1860 illustration in Harper’s Weekly.

Although there’s a heaping helping of irony in it, it seems we’re busy adding competition to a holiday meant to celebrate gratitude, cooperation and community. The holiday? Thanksgiving (and the competition is not just football). There’s a constant din now about which culture, which state, which people celebrated the first Thanksgiving.

Surely the pilgrims were first (Or was it the Native Americans centuries before Europeans settled the continent?), in gratitude for the bounteous harvest of 1621.

No! No! They just had the best publicists. Jamestown beat them by a decade, holding their first thanksgiving prayer service to mark the coming of a lifesaving round of ships and settlers in the spring of 1610.

But it couldn’t be the English in Virginia or Massachusetts, because in 1864 French Huguenots in Florida celebrated it (the year before the Spanish destroyed the colony).

But it couldn’t be the French because before the Spanish wiped out the French colony, that nation’s explorers celebrated a first Thanksgiving in Texas in 1541.

I suspect that they are all wrong (except maybe the Native Americans) because I’m sure that in the difficulties of life, humankind (in Old and New Worlds) has always and hopefully often taken time to offer prayers and hold feasts of Thanksgiving, in gratitude to Deity.

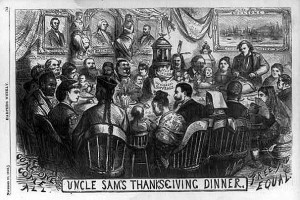

We just marked the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s immortal words at Gettysburg last week, and I think it worthwhile to remember another Thanksgiving and another Lincoln 150th anniversary. It was just 150 years ago that this nation (the United States of America), officially began celebrating a national and annual “Day of Thanksgiving and Prayer.”

A Library of Congress Congressional Research Service report notes:

President George Washington issued the first proclamation calling for “a day of public thanksgiving and prayer” on Thursday, November 26, 1789. Six years later, Washington called for a second day of thanksgiving on Thursday, February 19, 1795. Not until 1863, however, did the nation begin to observe the occasion annually.

Days of Thanksgiving had been celebrated in many states, regions and even periodically at the national level before 1863—some of it due to the diligent efforts of Sara Josepha Hale who lobbied for a unifying national Thanksgiving celebration, but it was with these words (extracted from the October 17, 1863, edition of Harper’s Weekly and apparently written by Secretary of State Seward; courtesy of http://www.sonofthesouth.net) that we as a nation held our first Thanksgiving as an annual celebration day:

A Proclamation by the President of the United States of America.

THE year that is drawing toward its close has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added which are of so extraordinary a nature that they can not fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever-watchful providence of Almighty God.

In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity, which has sometimes seemed to invite and provoke the aggressions of foreign states, peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed every where, except in the theatre of military conflict, while that theatre has been greatly contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union.

The needful diversions of wealth and strength from the fields of peaceful industry to the national defense have not arrested the plow, the shuttle, or the ship. The axe has enlarged the borders of our settlements, and the mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals, have yielded even more abundantly than heretofore. Population has steadily increased, notwithstanding the waste that has been made in the camp, the siege, and the battle-field; and the country, rejoicing in the consciousness of augmented strength and vigor, is permitted to expect continuance of years with large increase of freedom.

No human counsel hath devised, nor hath any mortal hand worked out these great things. They are the gracious gifts of the Most High God, who, while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy.

It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently, and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and voice by the whole American people; I do, therefore, invite my fellow-citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea, and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a Day of Thanksgiving and Prayer to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the heavens. And I recommend to them that, while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners, or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty hand to heal the wounds of the nation, and to restore it, as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes, to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquillity, and union.

In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my hand, and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington this third day of October, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and of the independence of the United State the eighty-eighth.

By the President: Abraham Lincoln

William H. Seward,

Secretary of State

In the end, it doesn’t matter who held the first Thanksgiving. It’s just important that we take time to pray and offer thanks for all that God has given us.

Happy Thanksgiving!

The post The First Thanksgiving: 150 Years Ago by Proclamation appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

November 20, 2013

Pericles: A Life of Ease and Love . . . Delayed

The prince’s ship sinks in storm at sea, leaving Pericles the lone survivor on a foreign shore.

I felt as if I were on a stormy sea as I started to read Pericles, Prince of Tyre. I’d never seen or read the play, but when it introduced incest in its early lines, my head nearly began to ache and my stomach to churn.

It wasn’t a topic I wanted to think about, and, just having finished the bloody Titus Andronicus, I wasn’t looking for another “yuck” play. Momentarily, I had the impulse to put it down, never finish it, so I could get my equilibrium back. But I persevered—as I had no choice if I wanted to reach the goal of reading all of Shakespeare by next April. Happily, what I thought was a turbulent sea smoothed quickly as incest references merely heightened opening drama and quickly faded from the play.

Pericles is a Shakespearean romance, originally listed as a comedy. The British Library notes the play’s sources include:

“John Gower, De Confessione Amantis (1554). Book 8 of this work suggested the figure of Gower, who acts as a chorus in Pericles. It also provided Shakespeare with the main outline of his plot, the names of places and characters, and a number of passages in the play.

“The Patterne of Paineful Aduentures , translated by Lawrence Twine (1607). It is not possible to tell which edition between 1576 and 1607 Shakespeare used. Twine’s novel influenced scenes 1, 3, and 6 in act 4.

“Barnabe Barnes, The Diuils Charter (1607). This influenced the chorusses spoken by Gower.

“John Day, William Rowley, George Wilkins, The Trauailes of the Three English Brothers (1607). This work also influenced Gower’s chorusses.”

Pericles is a play of happiness and ease delayed. Pericles has it all, with the exception of a wife, when the play starts. Unfortunately, like many other princes searching a companion, he seeks the hand of the beautiful daughter of the great Antiochus, King of Antioch. Antiochus requires any worthy prince seeking the hand of his heir to solve a riddle. Many princes have tried and many failed, with death being the agreed upon outcome of failure.

Pericles takes the riddle’s risk, not knowing that it is a Catch-22 for Pericles cannot survive either guessing correctly or wrongly the riddle. The wicked Antiochus has created a riddle that reveals his own dark secret—his incestuous relationship with his fair daughter. If Pericles guesses incorrectly, he has agreed to his own death. But if he guesses correctly, powerful Antiochus surely will surely put him to death for he cannot have Pericles spread his secret among the ancient city states. (Not only was Antiochus wicked, but apparently he was a dullard as well: Why would he code his sin into the riddle?)

Pericles understands the riddle, and Antiochus realizes he has deciphered it. Pericles flees, and Antiochus sends an assassin, Thaliard, after him. Thaliard, was clearly a man of foresight, for he promised Antiochus, “My lord, if I can get him within my pistol’s length, I’ll make him sure enough: so, farewell to your highness.” If you look at it literally, it’s not much of a threat to Pericles for pistols would not be invented for more than 1,000 years. Count it as one more Shakespearean anachronism.

Prince Pericles abandons his hometown, Tyre, to save it from the forces of Antioch which surely will come to destroy him. He leaves a trusted counselor, Helicanus, to manage the kingdom in his absence. That’s where the adventure begins. A shipwreck later, he meets a wonderful woman whom he marries, and they settle down to a happy life, with a child on the way. But Heaven is deeply involved in events, charring Antiochus and his daughter by lightning, opening the way for Pericles to return—and he must quickly or lose forever his kingdom. Sounds like the play could end there in happiness, but the gods had other plans.

Pericles and his fair bride take a ship toward Tyre, but again bad weather beats upon the prince’s vessel, and tragedy once more strikes: His wife dies in child-birth. He is clearly not meant to be a happily married monarch. The sailors “force” him to throw her body over the side for a sea burial because of sailor superstitions. Luckily they first seal her up in a waterproof trunk. Why lucky? Because she’s not dead, she’s “only mostly dead,” and she lands in the hands of a man of Ephesus, Cerimon—a bit more charitable than Miracle Max—who resuscitates her for free, then sends her to a nunnery, or at least to the famed temple of Diana in Ephesus.

In the meantime, Pericles drops his daughter off at the home of friends, Cleon and his wife, whom he saved earlier from starvation. They’re very loyal to him and promise they’ll care for the child as if she were their own, and they do, until she gets older and outshines their daughter. Then they try to kill her, but pirates save her or kidnap her, depending on your perspective. They carry her back to their ship, then sell her into prostitution. But she is every panderers’ nightmare, for she shames all potential customers into repenting.

Again in the meantime, Pericles returns home, takes his kingdom. More than a decade later, he goes to retrieve his daughter, Marina. (Why so long? I asked myself.) He learns from his friends that the child died, and they have erected a fabulous monument to her “cherished” memory.

Pericles is destroyed, refusing to speak to anyone. His vessel sails to the very town where Marina’s masters have failed to turn her from her virtue. She is now a respected young teacher in the town. To wrap the plot up quickly: Father and daughter are reunited, grieving only that wife and mother is lost. Diana–the god–appears directing Pericles to the temple of Diana at Ephesus. They go to make an offering and are joyously reunited with the priestess of the temple–Pericles’ wife and Marina’s mother. Happy ending. Lots of pain for Pericles and his family getting there, but a fun read.

One of the things I liked most in the play is that Marina, placed in a situation that threatens everything she is, does not need to count on the arrival of a knight or cavalry, but saves herself with her own wit, strength, virtue and gifts.

The play cautions against jealousy and lust and elevates virtue, loyalty, goodness and kindness. Perhaps Gower, the chorus, captures it best at play’s end:

In Antiochus and his daughter you have heard of monstrous lust the due and just reward [heaven’s bolt of lightning]: In Pericles, his queen and daughter, seen,— although assail’d with fortune fierce and keen, virtue preserved from fell destruction’s blast, led on by heaven, and crown’d with joy at last: In Helicanus may you well descry a figure of truth, of faith, of loyalty: In reverend Cerimon there well appears the worth that learned charity aye wears: For wicked Cleon and his wife, when fame had spread their [jealousy-caused] cursed deed, …the gods for murder seemed so content to punish them….”

Pericles, Prince of Tyre earns three bards:

Quotes I liked:

Helicanus: They do abuse the king that flatter him: for flattery is the bellow blows up sin; the thing the which is flatter’d, but a spark, to which that blast gives heat and stronger glowing; whereas reproof, obedient, and in order, fits kings, as they are men, for they may err.

Pericles: Thou art no flatterer: I thank thee for it

Pericles: ‘Tis time to fear when tyrants seem to kiss.

Pericles: Tyrants’ fears decrease not, but grow faster than their years

Pericles: I’ll take thy word for faith, not ask thine oath: who shuns not to break one will sure crack both

Dionyza: For who digs hills because they do aspire throws down one mountain to cast up a higher.

Gower: Losing a mite, a mountain gain.

Pericles: Wind, rain, and thunder, remember, earthly man is but a substance that must yield to you

3rd Fisherman: Master, I marvel how the fishes live in the sea. 1st Fisherman: Why, as men do a-land; the great ones eat up the little ones: I can compare our rich misers to nothing so fitly as to a whale; a’ plays and tumbles, driving the poor fry before him, and at last devours them all at a mouthful: such whales have I heard on o’ the land, who never leave gaping till they’ve swallowed the whole parish, church, steeple, bells, and all.

Simonides: Opinion’s but a fool, that makes us scan the outward habit by the inward man.

Simonides: I hope is none that envies it. In framing an artist, art hath thus decreed, to make some good, but others to exceed

1st Knight: We are gentlemen that neither in our hearts nor outward eyes envy the great, nor do the low despise.

Pericles: O you gods! Why do you make us lover your goodly gifts, and snatch them straight away?

Gower: No visard does become black villainy so well as soft and tender flattery.

Next Up: King Lear

The post Pericles: A Life of Ease and Love . . . Delayed appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

November 13, 2013

The Real Thomas and Mary Rathbone

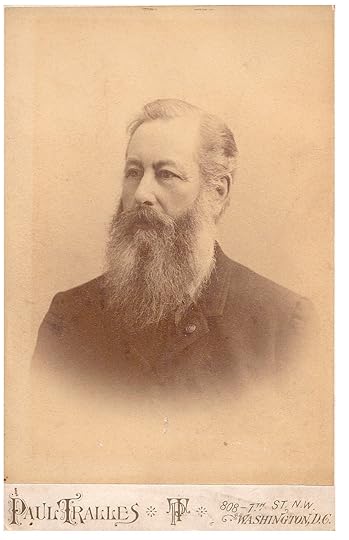

Thomas Rathbone served in the US Army before and during the Civil War.

In the final chapters of A River Divides, fictional Virginian Betsy Henderson meets a very real Washington City resident calling himself Thomas Rathbone and his wife, Mary. Betsy and the couple become fast friends, perhaps sensing a common flight from their pasts.

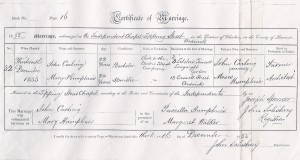

Thomas Rathbone was born under a different name—John Carling—to John Carling and Mary Ann Woodcock Carling on October 9, 1833 in Otley, Yorkshire, England. He, still calling himself John Carling, “a bachelor,” married Manchester native and “spinster” Mary Humphries, two years his senior, in Lancashire in 1855. So when they met Betsy, they would have been in their early thirties and been married a little more than eight years.

The Carlings-turned-Rathbones eventually had seven children, three of whom—John, Godfrey or “Teddy”, and Mary Louisa—were born before they migrated to the US. Their fourth child, Bertha, was born in late August 1864 and lived until 1957.

In England, Thomas worked as a clerk for the Electric Telegraph Company. He changed his name–according to family lore–to escape debtors’ prison for his brother’s debts and fled to America just before the Civil War. He left his family in England, expecting them to follow as soon as possible.

John, now Thomas, joined the US Army in May 1860 and served as a private, then lance corporal, in New York harbor until July. He recruited for the army in New York from then until early 1863. Presumably by this time, Thomas had suffered hearing loss due to close work with cannons.

Thomas Rathbone, previously John Carling, was a founding member of the Lafayette Post of the Grand Army of the Republic.

On January 2, 1863, he began working in the office of the Adjutant General of Army, Washington City. His wife and three children joined him in the US on Good Friday, 1863, after crossing the Atlantic on the ship Vanguard, and shortly thereafter he left the army (as a sergeant) to work as a civilian clerk in the office of the US Provost Marshal General. He became an US citizen January 8, 1864.

From July 1864 to January 1865, he served as First Lieutenant in the War Department Rifles, defending the capital.

After the war, he served as clerk in auditor’s office of the US Treasury, where he served for many years as chief of the bookkeeper’s division. He was also for a while a correspondent for The Evening Star and a founding member of the Washington, DC-based Lafayette Post of the Grand Army of the Republic. He was very knowledgeable of law and practice in his clerk work and was referred to as “the walking encyclopedia” of the Treasury Department. He retired in 1920 at about age 87 because the law required it.

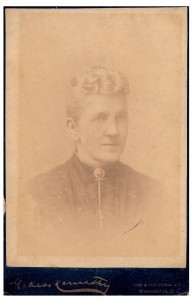

In 1855, Mary Humphries married John Carling (later Thomas Rathbone) in Lancashire, England. They had seven children.

At some point, Thomas purchased and moved his family to the Octagon House in Hyattsville, Maryland. According to the book Images of America: Hyattsville, the Octagon house “was built by Bladensburg druggist Henry T. Scott around 1853, its construction was attributed to a Mr. Swain. The spacious entry hall contained the stairs and opened on the main floor into only two rooms, the upper levels having two large rooms and one small one. An addition, the ‘trailer,’ was added to accommodate larger families.”

Mary and Thomas Rathbone moved their family to the Octagon House in Hyattsville, Maryland.

The house was “bulldozed in 1955 for construction on the spacious grounds of a row of modern houses on little lots.”

Mary Rathbone passed away January 5, 1923, and Thomas followed May 1, 1924. Mary and Thomas are both buried at Ft. Lincoln Cemetery in Brentwood, Maryland.

(My apologies to the real Mr. and Mrs. Rathbone for the liberties I took with their lives in A River Divides).

They were John Carling and Mary Humphries when they married in England, 1855.

Sources:

Damron, Andra on behalf of the Hyattsville Preservation Association. “Images of America: Hyattsville.” Arcadia Publishing. 2008. Print.

Puerzer, Ellen. October 2009. Hyattsville. Inventory of Older Octagon, Hexagon and Round Houses. October 22, 2013. From http://www.octagon.bobanna.com/MD.html.

Thomas and Mary Rathbone family records used in this post are in possession of and used by courtesy of Amy I. Anderson, 2nd great-granddaughter of Thomas and Mary Rathbone.

The post The Real Thomas and Mary Rathbone appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

November 6, 2013

Titus Andronicus: Unbelievable, Disgusting,Better Left Unread

Aaron, the Moor and slave to the queen of the Goths and empress of Rome, protects his unexpected child in Titus Andronicus.

Of all the Shakespeare’s plays I’ve read so far, Titus Andronicus is the one I would like to have never read.

Titus Andronicus must have been written and presented to shock (or disgust) Elizabethan theater patrons. It did comment on some traditional human foibles and attributes that often play a part in Shakespeare’s plays, and it was a descendant of several ancient (albeit disgusting) sources and stories, but Titus Andronicus—not the band—doesn’t work as a myth, reality or dream. For me, it’s just—yes you probably have guessed it—disgusting and a waste of time.

In the play, Titus Andronicus is a popular conquering general, suggesting he has a powerful intellect and dominant will. His brother is a Roman Tribune. It should have been disaster for anyone to tinker with this family. But the two men are played over and over and over again as fools, only perceiving the motives of others and the accompanying disasters after the family is smitten.

The Roman emperor, Saturninus, who rises to power at the goodwill of Titus Andronicus, shows an astounding naiveté and profound lack of situation-saving judgment and curiosity, from the beginning to his abrupt end. Then there’s the queen of the Goths, presented to us as sublimely subtle (and very lustful), yet whose haste in revenge and stupidity in lust wholly destroys her “subtle” work. And don’t forget the queen’s slave, a Moor named Aaron, who becomes an obvious image and personification of the Devil, in a bow to the racist English audience of the late 1500s.

All in all, Titus Andronicus and its story demand that we (and playgoers over the centuries) suspend logic and reason.

Grace Starry West in her Classical Allusions in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus notes the play “is generally considered Shakespeare’s worst” and has 53 allusions in the play. I suffered through each allusion as I read–they distracted from the plot (but why complain about that, as any distraction from this story is welcome relief). Fifty-three classical allusions apparently matches the total in , but the allusions in Troilus fit naturally and neatly into that tragedy. The allusions in Titus Andronicus seem forced.

The regretful plot: Titus Andronicus returns to Rome triumphantly after defeating the Goths. He brings, to parade through Rome, the queen of the Goths and her three awful sons. Titus puts to death one of the sons for his actions against Room. The queen had begged Titus not to do it, but to show mercy. He doesn’t, and she turns to revenge. Meanwhile, Titus supports Saturninus as emperor, and has promised his daughter, the fair and virtuous Lavinia, as wife to the new emperor.

But Titus’s sons, Lavinia and the emperor’s brother Bassianus have a different plan, and take Lavinia to marry Bassianus, as she had earlier been pledged to him. Titus is outraged and kills one of his sons for treason (unlikely I’m sure). The emperor calms down Titus. Saturninus doesn’t care, he’ll just marry the conquered queen of the Goths. Once he does, she begins her campaign of revenge.

Her sons want their way with Lavinia, so the empress has them kill Bassianus, rape Lavinia, cut out her tongue and cut off her hands so she can’t implicate them. (These are not nice people.) She then frames two of Titus’s three remaining sons for Bassianus’ murder. (It’s an unmentioned miracle, but Lavinia doesn’t bleed to death.) Instead she returns to live with her family. The emperor discovers his brother’s murder, and orders Titus’s sons held, but never asks about Lavinia. (Amazing. No wonder Rome fell.)

The plot is just picking up steam: Titus’s two framed sons are to be put to death, but the senate offers their lives if one of the other family members will cut off a hand. (Absurd, I know.) So, Titus cuts off a hand and sends it to the senate, which sends it back mockingly with the heads of his sons. (I’m embarrassed for myself and the Bard to repeat the plot.)

All the while, the queen is two-timing the emperor with her Moor. Suddenly, the queen gives birth to a baby, but the baby is dark-skinned. The Moor, Aaron, escapes with the baby to save its life.

Finally, Titus invites everyone to his house (including his last son who has joined forces with the Goths and has returned to conquer Rome). There he serves up the queen’s sons, who he’s killed, to their mother as a dainty dish. He unveils Lavinia for the emperor who suddenly wants to know who did this. (Come on. Where has he been the entire play?) Titus then kills Lavinia for her shame, reveals the content of the dinner—her sons—to the empress and stabs her. The emperor then kills one-handed Titus, and Lucius—Titus’s remaining and returning son—kills the emperor.

Aaron, the Moor slave, has already been captured by Lucius and confessed to all. He admits he has been the mind, motivation and evil behind the queen/empress. His only regret: “If one good deed in all my life I did, I do repent it from my very soul.” Earlier he proclaimed, “If there be devils, would I were a devil, to live and burn in everlasting fire.” He is sent off to death.

My only regret is that Shakespeare wrote Titus Andronicus and that it has survived for more than 400 years. The plot is unbelievable (and disgusting).

The play has several disgusting sources. According to Shakespeare-Online:

There is a possibility that Shakespeare relied upon a poem circulating in 1570, unfortunately titled, A Lamentable Ballad of the Tragical End of a Gallant Lord and of his Beautiful Lady, With the Untimely Death of Their Children, Wickedly Performed by a Heathen Blackamore, Their Servant: The Like Seldom Heard Before. We know that, as a minor source, Shakespeare used Ovid’s tale of Progne and Philomela (as found in Metamorphoses), which he cited almost verbatim in Act IV, Scene I (42) of the play.

Philomela is referenced many times in the play. She was raped and had her tongue severed, but her hands remained to weave an accusation against the perpetrator. In revenge, she and her sister serve her rapist his son in a meal.

Also mentioned by Shakespeare-Online is the influence Seneca’s Thyestes. In that Roman drama, a brother, for revenge, slays his nephews and serves them to their father for dinner. The personal significance of that association is that I used quotes from and references to Thyestes several times in my novel Beyond the Wood, because a father eating his sons perfectly captures the American Civil War, where governing men from the North and governing men from the South consumed their own progeny in the vanity of war.

The theme of Titus Andronicus seems to be the destructive nature of revenge, outright racism, the consequences of lust, and, lastly, no matter how capable you think someone in this play is, they’re not.

For absurdity, sordid plot, racism, pandering to his audience, and awkward and overuse of allusions, I give Titus Andronicus one Bard (and that includes grade inflation of at least two Bards):

Quotes I like:

Tamora: Sweet mercy is nobility’s true badge

Tamora: O cruel, irreligious piety!

All: He lives in fame that died in virtue’s cause.

Titus: Why, foolish Lucius, dost thou not perceive that Rome is but a wilderness of tigers?

Tamora: I have touched thee to the quick

Aaron: I know thou art religious, and hast a thing within thee called conscience

Next Up: Pericles, Prince of Tyre

The post Titus Andronicus: Unbelievable, Disgusting,Better Left Unread appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

October 30, 2013

Stonewall Jackson: A Character of Character

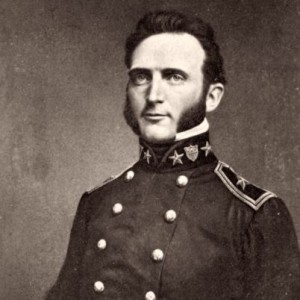

Stonewall Jackson, enigmatic general of the Confederacy.

I woke yesterday thinking about Stonewall Jackson. Odd, I know, and I have no explanation for it. I can’t remember the last time I thought of him. So, it was odd, but that word—odd—seems to fit neatly into any discussion of the legendary felled Confederate General.

Since I was thinking about him anyway, I decided I’d write down a few favorite Stonewall anecdotes and quotes.

I pulled out my copy of James I. Robertson’s outstanding biography of Jackson (which is one of my 25 favorite Civil War books) and at some point ended up on Goodreads reading some of the reviews of the book. One review began, “I was hesitant to read a book about Stonewall Jackson for the simple reason that I hate the guy.” Slavery seemed the focus of the reader’s hatred, but as an aside he liked the book, giving it a four-star rating. On the other hand, a five-star rater’s lone comment was, “One of my favorite role models as a young man.” The two comments seemed to capture two of the constant and conflicting comments that arise when discussion turns to Stonewall Jackson.

Stonewall, one of the members of the Confederate “godhead” (Lee, Jackson, Stuart–these names also, for what it’s worth and as no surprise, are the monikers of high schools in Northern Virginia near where I grew up), brings out strong emotions on both sides. Many claim the Confederacy lost its last hope of winning the war when friendly fire downed Jackson. Others turn from him in disgust, alleging that he supported slavery.

No matter how you feel about him, he is fascinating, and I side with those who admire him for his character. I find him particularly interesting because he was such a character. Definition 9b on freedictionary.com for the word “character” seems to capture the general: “A person, especially one who is peculiar or eccentric.” It was his success and his eccentricities that made him a near-mythical figure in the 1860s and that intrigue us today.

With Thomas Jonathan Stonewall Jackson, nothing seems as we expect: He supported a culture and government that supported slavery, accepted slavery as God’s will, personally benefited from slave labor; yet skirted Virginia law by teaching black children in a Sunday school. His faith in Christ and associated charity and kindness for humankind seemed, once he acquired it, to drive all he did; yet in his military efforts, he seemed to embody the militancy of the ancient and at times wrathful and merciless army of Israel.

Here are three favorite stories and quotes worth contemplating:

“I am more afraid of that than I am of Yankee bullets”

Stonewall Jackson was for the most part a teetotaler; not significant in itself, however, his reason and self-control are the true lesson.

One Surgeon McGuire pressed a drink medicinally on Jackson one cold night, and asked the general as he sipped it, “Isn’t the whiskey good?”

Stonewall responded, “Yes, very. I like it, and that’s the reason I don’t drink it.”

On another occasion, when asked why he abstained, Jackson answered, “Why, sir, because I like the taste of [liquors]. When I discovered this to be the case, I made up my mind at once to do without them altogether.” And finally, on one occasion, he assured a listener, “I am more afraid of [liquor] than I am of Yankee bullets.”

His self-denial and self-discipline make me pause to review my self-control.

“Don’t take counsel of your fears”

Stonewall Jackson advised cartographer Jedediah Hotchkiss to “Never take counsel of your fears.”

On an occasion when Stonewall Jackson and his cartographer Jedediah Hotchkiss were arriving toward dark at their camp on the mountains not far from Waynesboro, Virginia, they were greeted with countless campfires twinkling at them across a wide expanse of mountain. Worried they would never find their headquarters amid so many fires, Hotchkiss commented, “General, I fear we will not find our wagons tonight.”

Jackson responded, “Never take counsel of your fears.”

That seems like good counsel to us all.

“My Personal Comfort is not to be consulted”

Early in his Christian experience, Jackson attended church one Sunday when the minister admonished his congregants to attend weekday prayer services where each male member had a responsibility to lead the prayer.

Jackson approached the minister, explaining that he had little experience in public speaking and might not succeed at praying in such a meeting, but added, “If you, as my pastor, think it is my duty, call on me whenever you think proper. My personal comfort is not to be consulted in the matter.”

The minister, a Dr. White, did call on him, and Jackson’s fears proved justified and prophetic. Robertson reports in his Jackson biography, “words and sentences tumbled forth in utter confusion.” Weeks went by without another invitation to pray, at which point Jackson again approached Dr. White. “Are you trying to save me pain?” he asked. After receiving a response, he declared, “If it is my duty to lead in prayer, then I must persevere in it until I learn to do it aright, and I wish you to discard all consideration for my feelings.”

Dr. White called on Jackson again, resulting in a more positive experience for Jackson and the listeners. In time, Jackson prayers improved dramatically.

The drive Jackson had for duty and for self-improvement (even though the latter at times came slowly) and his refusal to allow his personal failures to deter him are great reminders to us all.

Hate him or love him, Stonewall Jackson gives us a lot to think about and reminds us it’s hard to judge others without understanding their intentions. (And rarely, if ever, do we see clearly into the hearts of others.)

Source: Robertson, James I.. Stonewall Jackson: the man, the soldier, the legend. New York: Macmillan Pub. USA , 1997. Print.

“I am more afraid of that than I am of Yankee bullets” anecdote and quotes are from pp. 299, 418, and from note 48 on p. 842

“Never take counsel of your fears” anecdote is on p. 457

“My personal comfort is not to be consulted” anecdote is on pp. 137-138

The post Stonewall Jackson: A Character of Character appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

October 24, 2013

Cymbeline: Written with Scissors and Glue

Posthumous adorns his wife’s, Imogen, wrist with a vital-to-the-tale bracelet.

I am convinced Shakespeare was having fun with us when he wrote Cymbeline.

It happened like this: He was tired of writing one day and decided to present of one of the old plays at the Globe. But that didn’t seem right. Sparked by his desperation, a inspired solution flashed upon him: He knew how he could give his audience something new and fresh.

He laid out all of his plays, cut each one into slips of paper, each paper containing a plot element from a past or soon-to-be-finished play. He stuffed the paper strips in a hat and had each of his King’s Men players pull out a slip of paper. Then, without looking at them, he glued them together in random order and proudly proclaimed the result his new play.

The first passage pulled out of the hat was from King Lear. Hum. He had to change the name of the play and the characters, at least. So he quickly scribbled out the name Lear and replaced it with the only other early monarch of the Britons (who wasn’t legendary Arthur) he could remember from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain)—Cymbeline. And weren’t Lear and Cymbeline related anyway. There, he had his title and subject.

Now the plot: The next slip contained the portion of Romeo and Juliet where the beloved young woman is given a potion so she could repose in death-like splendor, without taking that last step towards the final light. Feigned lover’s death? Shakespeare gazed at the paper for just a second. Obvious! He’d stick that element in the play. The young heroine could be given a sleeping potion. The husband would think her dead. “Great idea!” proclaimed the Bard a bit louder than he intended. “I’m glad I came up with it twice.” And he stuck it in the play.

The passage he pulled from challenged him, but soon he concluded he’d use the test of a lover’s virtue, and with this free do-over, he’d make it work out better.

A slip of paper from Hamlet reminded him of the Dane’s ghostly father. But he wanted the show to attract families for the Saturday matinees, so he tossed in a few more related spirits for a more familial feel.

He looked down at the glued paper again. This time he saw a cutting from Twelfth Night. Perfect! He could have the princess dress up like a man to serve an authentic man as a faithful and beloved servant. It had worked great in Twelfth Night–very popular, so he included it in Cymbeline.

The next play in his “compilation” was the “taking” of the king’s child. The Winter’s Tale was a work in progress in his top left desk drawer, so it was fresh on his mind. It would add a great twist to the story! So he added it to Cymbeline, but this time it was not to save the child from a raving king, but to punish an unwise king. At that point, he remembered the final scene from the Tale. It was such a grand summing up of all those loose ends in the play—as good as any who-done-it he’d ever read—so he gave Cymbeline an even better wrap where everything was revealed and restored.

Imogen, fictional daughter of Cymbeline, flees to the country.

At that point, he read over his draft and realized he had plagiarized himself (not just another playwright or ancient writer), and this worried him. He pondered and pondered about how to get out of it. It’s ok to copy and imitate the work of others, especially when you always end up raising the quality of the work, but how do you improve upon the Bard?

He was troubled, but just for a short breath, for soon his genius kicked in, revealing an escape. He’d make it a fairy-tale, without the fairies. He’d write in the ever-unpopular evil stepmother stereotype, and maybe even have her try to poison the beautiful princess. But it needed something bigger, so he called in the big gun. A cameo by that chief god Jupiter would be fantastical and raise the whole play to mythical heights. Yes, a mythical play. A Roman God. A British King. A fair princess ever separated from her not-quite-a-prince husband. True, abiding love. A princess always at risk.

This was great formula. The play would be better than the plays the other guy had been supplying him—you know the guy: the one who wanted to stay anonymous and kept giving Will stellar plays and begging him to put the Shakespeare name on them. This was William’s chance to become the real Shakespeare. He trembled with excitement.

And that’s how Cymbeline was written.

It left the play with more twists and turns, more ups and downs and dangers than a narrow mountain road during a rock-slide. Part tragedy, part romance, part comedy. How do you categorize it? Originally, it was a comedy, but the latest trend is to call it romantic comedy.

It’s the story of a clearly incapable-of-discernment king in ancient England. His evil second wife and equally bad stepson use and deceive him, but he believes they adore him. His daughter, Imogen, who does adore him, has raised his ire by marrying a man she loves. Both she and her husband are marvelous, perfect. But Cymbeline, the king, wanted her to marry someone more worthy of her; someone like his stepson Cloten. Imogen’s husband, Posthumus, is banished.

Posthumus turns out not to be so perfect in judgement. He brags of Imogen’s loyalty and beauty and accepts a wager from an Italian–of course–to test Imogen’s faithfulness. Imogen proves exceedingly fair and faithful, but the Italian cheats to steal information and a bracelet from Imogen to “prove” her guilt.

In the meantime, under the misguidance of his queen, Cymbeline refuses to pay tribute to Rome and Augustus Caesar. Thus Rome prepares to crush the Britons. That’s where the linear plot twists upon itself over and over again: Imogen ends up wearing a lad’s clothes in supporting Rome’s battle with England. Posthumus, who believes he’s killed Imogen for her supposed wantonness, wearing commoner’s clothes ends up fighting ferociously for Briton in hope of dying. Two royal sons, earlier kidnapped and assumed dead, come out of their cave-home to crush the Romans. And Cloten, the want-to-be-king clod, borrows Posthumus’s clothes to kill Posthumus and force Imogen, but loses his head over her. And the queen: You know what happens to evil stepmothers, although this one confesses to all her dastardly deeds as she fades.

Cymbeline is a romantic comedy, so it all works out in the final scene with lots of forgiveness going around, a fine reconciliation with Rome, and with Imogen losing the kingdom to a brother she didn’t know existed. Never has a kingdom been lost with more joy.

Folger Shakespeare Library says of the play:

Cymbeline displays unusually powerful emotions with a tremendous charge. Like some of Shakespeare’s other late work—especially The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest—it is an improbable story lifted into a nearly mythic realm.

Words that come to mind when I think of the play are forgiveness, faithfulness, loyalty, and kings tend to have poor judgement.

Cymbeline was enjoyable and fun. It wasn’t one of my favorites, and it did seem to borrow elements from lots of other Shakespeare plays, so I’m going to give it a respectable four Bards:

Quotes I liked:

Cloten:We will nothing pay for wearing our own noses.

Imogen:I see a man’s life is a tedious one

Imogen:Plenty and peace breeds cowards; hardness ever of hardiness is mother

Cloten:It is not vainglory for a man and his glass to confer in his own chamber.

Lucius:Some falls are means the happier to arise.

Pisanio:Fortune brings in some boats that are not steer’d.

Posthumus:The strait path was damn’d with dead men hurt behind, and cowards living, to die with lengthen’d shame.

Jupiter:Whom best I love I cross; to make my gift, the more delay’d, delighted. Be content

Jupiter:He shall be lord of Lady Imogen, and happier much by his affliction made

Gaoler:I would we were all of one mind, and one mind good

Posthumus:The power that I have on you is to spare you; the malice towards you to forgive you: live, and deal with others better.

Up Next:Titus Andronicus

The post Cymbeline: Written with Scissors and Glue appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

October 15, 2013

Doomed Bardic Romance of Antony and Cleopatra

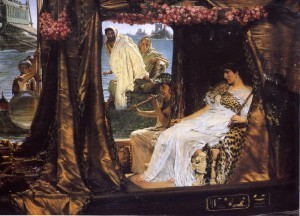

Antony and Cleopatra presents us an odd twist: The monumental

Cleopatra awaits Antony on her barge.

Antony of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar who used his strong mind, his powerful will, his courage and military genius to quiet senatorial rebellion becomes in the Bard’s hands and in the amorous arms of the queen of the Nile a doting fool. We knew he could be sensitive. We saw him mourn Brutus‘ death, but that display of humanity hardly prepared us for this portrayal of catastrophic collapse of independence, strength, courage and judgment.

In the tragedy, we see brief flashes of his former military brilliance and decisiveness, but they are quickly quenched by treachery and more often by the dominating power Egypt (Cleopatra) has over this Roman ruler. It makes him unwilling and too weak in the end to defend his (and her) interests.

Cleopatra’s retreat from the action at Actium brings Anthony’s fall. Painting at National Maritime Museum in London.

Cleopatra’s retreat from a naval battle (Battle of Actium) and Antony’s ensuing withdrawal assured his defeat and disgrace. Losing the battle to former ally and fellow Roman ruler Octavius, all that’s left for Antony is death by his own hand.

For Cleopatra, she must follow her betrayed lover into the shadows or be paraded and mocked in Rome. A smuggled-to-her asp quickly brings her painless, peaceful death (“the joy of the worm”).

In the aftermath of Julius Caesar’s death and the defeat of his assassins, Roman rule is divided geographically between three men: Octavius Caesar, Antony and Lepidus. Antony and Cleopatra, the play, traces the eclipse of the Roman Republic as first Lepidus falls, then Antony (only incidentally Cleopatra), leaving Octavius alone as Augustus Caesar, dictator of the Roman Empire and world and cornerstone of the then-possible Pax Romano.

The play is based on Plutarch and Samuel Day’s 1594 Cleopatra.

The message of Antony and Cleopatra? Lack of self control leads to destruction and being a Roman ruler is not a safe occupation and should be avoided if possible.

For pathetic, disabling, manipulative emotion being disguised as romance, I give Antony and Cleopatra one Bard:

Quotes I liked:

Messenger: The nature of bad news infects the teller.

Antony: What our contempts do often hurl from us, we wish it ours again.

Charmian: In time we hate that which we often fear.

Menecrates: We, ignorant of ourselves, beg often our own harms, which the wise powers deny us for our good; so find we profit by losing of our prayers.

Enobarbus: Every time serves for the matter that is then born in’t.

Lepidus: When we debate our trivial difference loud, we do commit murder in healing wounds.

Lepidus: What manner o’ thing is your crocodile? Antony: It is shaped, sir, like itself; and it is as broad as it hath breath: it is just so high as it is, and moves with its own organs: it lives by that which nourisheth it; and, the elements once out of it, it transmigrates.

Antony: If I lose my honor, I lose myself.

Antony: I have fled myself, and have instructed cowards to run and show their shoulders.

Antony: O, whither hast thou led me, Egypt? How I convey my shame out of thine eyes by looking back, what I have left behind ‘Stroy’d in dishonour.

Cleopatra: Is Antony or we in fault for this? Enobarbus: Antony only, that would make his will lord of his reason.

Enobarbus: I see men’s judgments are a parcel of their fortunes; and things outward do draw the inward quality after them, to suffer all alike.

Enobarbus: Mine honesty and I begin to square. The loyalty well held to fools does make our faith mere folly:—yet he that can endure to follow with allegiance a fallen lord does conquer him that did his master conquer, and earn a place i’ the story.

Enobarbus: To be furious is to be frighted out of fear

Enobarbus: When valour preys on reason it eats the sword it fights with.

Antony: My fortunes have corrupted honest men!

Octavius Caesar: The time of universal peace is near: Prove this a prosperous day, the three-nook’d world shall bear the olive freely.

Agrippa: Strange it is that nature must compel us to lament our most persisted deeds.

Cleopatra: Be it known that we, the greatest, are misthought for things that others do

Caesar: Make not your thoughts your prisons

Clown: A very honest woman, but something given to lie; as a woman should not do but in the way of honesty

Clown: I wish you all joy of the worm.

Next Up: Cymbeline

The post Doomed Bardic Romance of Antony and Cleopatra appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

October 10, 2013

Castle Thunder: Visiting the Southern Bastille

Castle Thunder, the Confederacy’s prison for political prisoners, women, slaves and deserters.

“Castle Thunder! What a horridly euphonious name for a prison place. So suggestive of doom and death. And so it proved to many a Confederate soldier, who, lying in the dungeons damp, or crowded into the common pens, for long weeks and months. . . .”

Sounds like a Southerner excoriating the North for the horrors of its military prisons during the Civil War, but Castle Thunder wasn’t a Northern prison, and the description comes from a just-after-the-war recounting in “Southern Opinion” about one of the few topics both sides could agree on: Castle Thunder—a unique Rebel prison entertaining men and women, misbehaving Confederate soldiers, captured escaped slaves, Union deserters, Union POWs and traitors—was a place of nightmares.

On March 1, 1862, Jefferson Davis increased the need for prison space by suspending writ of habeas corpus within 10 miles of Richmond, opening the path for arrest and incarceration of political prisoners.

The Castle opened for guests in summer 1862 in the heart of Richmond’s industrial district, combining three tobacco factories into a segregated (by race and gender) lockup. The entrance, offices and welcoming center to the prison faced Cary Street, between 18th and 19th streets–the former tobacco factory of William Greanor & Sons. It became the unwelcoming home for Southerner, soldier and civilian alike. Two smaller factories sided the main building. Whittock’s building was “used for negro quarters and prison for women”; and Palmer’s was “used for Yankee deserters.”

Combined, the buildings were designed for 1,400 prisoners, but at least at one point housed 3,000. The prison served the Confederacy to the end of the war, and in its difficult history, some executions were documented at the Castle.

The Confederates destroyed many Castle Thunder records before they left the capital and the buildings around the Castle burned as the government retreated from the city. But Castle Thunder (and Libby Prison) escaped the destruction. (In 1879, however, the Castle suffered–just delayed–the same fate, being gutted in a fire.)

The Union took over the prison when they occupied Richmond, and under its supervision Castle Thunder held Union political prisoners, Confederate soldiers and criminals. The supposed key to the Castle was smuggled North where it was sold to benefit orphans of fallen Union soldiers.

Castle Thunder Commandants

In its four-year run, the Castle had three commandants:

Captain Alexander used bucking and gagging as one punishments for prisoners at Castle Thunder.

The first was the most famous and infamous. Captain George W. Alexander opened the prison and oversaw the facility with a combination soft leather gloves for those prisoners he liked and an iron fist for others. His controversial methods led to a Confederate congressional inquiry where it was reported prisoners were strung up:

by the thumbs and raised up on their toes. . . . I don’t know how long they remained tied up, but from the best information they were kept sometimes eight hours. . . . I saw a man handcuffed around a post, raised up at first and afterwards cut down when his blood had stagnated. . . . Captain Alexander . . . put . . . men down in the pen outside, where they remained two or three days. They had no covering and it was raining. . . . I have seen prisoners whipped, . . . severely whipped on the buttocks with straps . . . . The whipping strap was secured onto wooden handles. They were made of harness leather or sole leather from eighteen inches to two feet in length. The blows were laid on about as hard as a man could do it. I have seen prisoners wear the same clothes for months until they were ready to drop off in rags. I think there have been instances of attempts to bribe the guard.

Another prison official testified:

I have seen on one or two occasions fifteen or twenty prisoners “bucked” and “gagged” at a time. The “gag” is effected by a stick inserted crosswise in the mouth, and the “buck” is to tie the arms at the elbows to a cross-piece beneath the thighs. They were generally ironed, wore ball and chain, and were charged with various offenses. I recollect now I only “gagged” one. I have seen the “barrel shirt” worn by a prisoner. The shirt is made by sawing a common flour barrel in twain and cutting armholes in the sides and an aperture in the barrel head for the insertion of the wearer’s head. The one I saw have the barrel shirt on wore it as a punishment for lying. He was tied up by the thumbs to the roof and stood on his feet, wearing it one day and part of the next day.

Congress exonerated the captain, but he was soon transferred because of later charges filed against him. Alexander was a playwright and kept a large, black Russian Bloodhound named Nero (or Hero) that some claimed he used to intimidate prisoners.

Late in 1863, Alexander was replaced by an urbane and efficient, but much less spectacular, commandant, Captain Richardson.

The March 2, 1865 Richmond Dispatch (Daily Dispatch) announced “Captain Lucian W. Richardson, for some time past commandant at Castle Thunder, has been honorably retired from the Confederate service on account of physical disability. His connection with the Castle ceased on Sunday last, since which time the affairs of that institution have been, and till further arrangements are made will be, under the charge of Captain Henry Callahan, the senior officer on duty there.”

Callahan oversaw the prison to war’s end and fled Richmond with the Confederate government. He returned to Richmond April 17 to surrender to Union authorities, who quickly released him on parole.

A Prison for Women

It’s variously estimated that about 100, more than 100 or hundreds of women were held at Castle Thunder–I haven’t seen any of the three verified.

Dr. Mary E. Walker, a four-month prisoner at Castle Thunder and the only woman to ever receive the Medal of Honor, poses in her “Reform Dress.”

But there were many incarcerated, including women held for spying, disloyalty, and Union military wives (and their children) who foolishly stayed behind in Winchester, Virginia, when the Union pulled out of the city. Escaped female slaves were imprisoned there. Several former female Confederate soldiers (Mary and Molly Bell and Millie Bean) whose gender was discovered were sent briefly to the prison till they could be placed in safety. No woman ever escaped from the Castle, but at least one internee, Mary Lee, gave birth to a child while locked up. Mary named her daughter Castellina Thunder Lee and often visited the prison after her release.

Most famous of Castle Thunder’s women prisoners was the first and only female recipient of the Medal of Honor Dr. Mary E. Walker who was captured by the military. She may have been spying for the North, but most Richmond residents were far more interested in her clothes. “She had a room to herself in Castle Thunder, and sometimes was permitted to stroll into the streets, where her display of Bloomer costume, blouse, trowsesrs [sic] and boots secured her a following of astonished and admiring boys.” She described it as “what is usually called the ‘Bloomer’ or ‘Reform Dress,’ which is similar to all ladies with the exception of its being shorter and more physiological than long dresses.” In short she wore trousers under a near-the-knee skirt or dress. Because of her incarceration, she suffered long-term health issues, her niece later reporting that she weighed 60 lbs. when she was exchanged after her four months in the Castle.

Sources:

“Castle Thunder.” Richmond Enquirer 12 August 1862. Web. 10 October 2013. <http://www.mdgorman.com/Written_Accounts/Enquirer/1862/richmond_enquirer_81262a.htm>

Graf, Mercedes. A Woman of Honor: Dr. Mary E. Walker and the Civil War. Gettysburg: Thomas Publications, 2001. Print.

Hanna, J. Marshall. “Castle Thunder in Bellum Days.” Southern Opinion, November 11, 1867. Web. 20 August 2013. <http://www.mdgorman.com/Written_Accounts/Other_Papers/southern_opinion,_11_2>

McClarey, Donald R. “Jefferson Davis and the Suspension of Habeas Corpus.” The American Catholic 7 February 2013. Little Vatican. Web. 10 October 2013. <http://the-american-catholic.com/2013/02/07/jefferson-davis-and-the-suspension-of-habeas-corpus>

No Title. New York Times 6 September 1879. Web. 10 October 2013. <http://www.mdgorman.com/Written_Accounts/NYC_Papers/new_york_times,_9_6_1879.htm>

Speer, Lonnie R. Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1997. Print.

“The Prisoners.” The Richmond Dispatch 8 July 1862. Web. 10 October 2013. <http://www.mdgorman.com/Written_Accounts/Dispatch/1862/richmond_dispatch_7862.htm>

“To be Evacuated.” Richmond Dispatch 18 August 1862. Web. 10 October 2013. <http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2006.05.0548%3Aarticle%3Dpos%3D29>

The post Castle Thunder: Visiting the Southern Bastille appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

October 7, 2013

Hitting the Shelves with “A River Divides” in Denver Post

A quick thanks to the Denver Post for highlighting award-winning Beyond the Wood‘s sequel, A River Divides, in its “Hitting the Shelves” feature.

A quick thanks to the Denver Post for highlighting award-winning Beyond the Wood‘s sequel, A River Divides, in its “Hitting the Shelves” feature.

A River Divides is set during late winter and spring of 1864 in Kentucky (one of the last states to free slaves), Virginia and the Washington City portion of the District of Columbia. The war reposes for winter, but there’s no shortage of action, intrigue and conspiracies (and romance). The narrative follows several of the characters from Beyond the Wood and adds several interesting ones.

We’ve begun the next–and I think last–book in the series and plan to have it out in 2014.

Thanks to everyone who’s been so supportive.

The post Hitting the Shelves with “A River Divides” in Denver Post appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

September 25, 2013

Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: Or is it the Tragedy of Brutus?

Senators seem to celebrate the murder of Julius Caesar in painting by French Artist Jean-Léon Gérôme. Original painting hangs in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

I liked Julius Caesar. It’s a tight play that effortlessly caught and held my attention. The plot is urgent and driving; moving quickly in a straight line—never lagging, never tempting us with a side story or comedic relief—to multiple tragic ends: Caesar’s, and more importantly Brutus’.

Julius Caesar was the first Shakespeare play I read (although I don’t remember being particularly fond of it as a 15 or 16 year old). Like many others before and since, I stumbled through it in a high school English class. And years later, about all I could remember were a few quotes: “Beware the Ides of March”; “Et tu, Brute?”; “Friend, Romans, Countrymen, lend me your ear.” Each one was easily recalled because of common references to them in modern culture.

My last memory was a little more surprising: The play introduced me to anachronisms. I still remember the teacher (who I can no longer visualize) explaining the mechanical clock referenced in Julius Caesar didn’t exist in ancient Rome.

The play’s name is a Shakespearean sleight of hand. We expect to see Julius Caesar revealed before our eyes, but the Bard enticed us to look the wrong way.

The play has little to do with Caesar. He is almost a passive character floating through scenes and circumstances created by others: He is in a procession where the soothsayer warns him of the Ides. We only hear that he has rejected the kingship offered him. He hears of his wife’s dream and warning, and she convinces him to stay at home, not go to the Senate. He is then flattered into ignoring the dream and going, as scheduled, to the Senate. He receives and rejects a plea of leniency as the backdrop to his assassination. He appears—silent to us—after his death as Great Caesar’s ghost. And, he receives the blows of the conspirators, especially the one from Brutus, responding to the man who is the true center of the play: “Et tu, Brute! Then fall, Caesar.”

Should it have been named “Brutus”? (Of course not. It was Shakespeare’s play, and he could name it whatever he wanted.) But the play is about Brutus:

His love of Julius Caesar

The machinations and flattery used to win him over to the opinion that Caesar threatened or would eventually threaten Roman liberties

His role in the final conspiracy

The consequences of his role.

Brutus is a sympathetic character. He is truly “an honorable man”—the words Marc Antony sarcastically uses to rouse the Romans against the conspirators in a fabulous speech—the highlight of the play for me and a speech that rivals Henry V’s Saint Crispin-day speech for effectiveness and beauty. And while Antony uses sarcasm to rile Rome, in quieter moments, we witness that he seems truly to hold Brutus as an honorable man. When Antony finds Brutus dead, he offers his last and most honest judgment:

This was the noblest Roman of them all:

All the conspirators, save only he,

Did that they did in envy of great Caesar;

He only, in a general honest thought,

And common good to all, made one of them.

His life was gentle; and the elements

So mix’d in him that Nature might stand up

And say to all the world, This was the man!

Brutus ends like the hollow men of TS Elliot’s poem The Hollow men, which borrows heavily from Shakespeare’s play, “Not with a bang, but a whimper.”

Shakespeare’s source for the story was Plutarch.

Envy, flattery and manipulation are counterbalanced by integrity and honor in Julius Caesar, and I give the play a rousing five bards:

Quotes I liked:

Brutus: The eye sees not itself but by reflection, by some other things.

Cassius: Men at some time are masters of their fates: The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves, that we are underlings. Brutus and Caesar: What should be in that Caesar? Why should that name be sounded more than yours? Write them together, yours is as fair a name; sound them, it doth become the mouth as well; weigh them, it is as heavy; conjure with ‘em, Brutus will start a spirit as soon as Caesar.

Caesar: He thinks too much: such men are dangerous.

Casca: It was Greek to me.

Cassius: Well, Brutus, thou art noble; yet, I see, thy honourable metal may be wrought from that it is dispos’d: therefore it is meet that noble minds keep ever with their likes; for who so firm that cannot be seduc’d?”

Cinna: O Cassius, if you could but win the noble Brutus to our party

Brutus: But ’tis a common proof, that lowliness is young ambition’s ladder, whereto the climber-upward turns his face; but when he once attains the upmost round. He then unto the ladder turns his back, looks in the clouds, scorning the base degrees by which he did ascend.

Brutus: Between the acting of a dreadful thing and the first motion, all the interim is like a phantasma, or a hideous dream

Brutus: O conspiracy, shamest thou to show thy dangerous brow by night, when evils are most free? O, then by day where wilt thou find a cavern dark enough to mask thy monstrous visage? Seek none, conspiracy; hide it in smiles and affability

Brutus: O, name him not: let us not break with him; for he will never follow anything that other men begin.

Decius Brutus: When I tell him he hates flatterers, he says he does,—being then most flatter’d.

Portia: Within the bond of marriage, tell me, Brutus, is it excepted I should know no secrets that appertain to you? Am I yourself but, as it were, in sort or limitation,—to keep with you at meals, comfort your bed, and talk to you sometimes? Dwell I but in the suburbs of your good pleasure? If it be no more, Portia is Brutus’ harlot, not his wife.

Caesar: Cowards die many times before their deaths; the valiant never taste of death but once.

Calphurnia: Your wisdom is consum’d in confidence.

Caesar: I am constant as the northern star, of whose true-fix’d and resting quality there is no fellow in the firmament. The skies are painted with unnumber’d sparks,—they are all fire and every one doth shine; but there’s but one in all doth hold his place

Caesar: Et ut, Brute?—Then fall Caesar!

Brutus: Not that I loved Caesar less, but that I loved Rome more.

Antony: Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears; I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him. The evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones; so let it be with Caesar.

Antony: O judgment! thou art fled to brutish beasts, and men have lost their reason.

Antony: For Brutus, as you know, was Caesar’s angel: Judge, O you gods, how dearly Caesar loved him! This was the most unkindest cut of all; for when the noble Caesar saw him stab, ingratitude, more strong than traitors’ arms, quite vanquish’d him: then burst his mighty heart

Antony: I have neither wit, nor words, nor worth, action, nor utterance, nor the power of speech, to stir men’s blood: I only speak right on

Antony: Mischief, thou art afoot.

Antony: Some that smile have in their hearts, I fear, millions of mischiefs.

Brutus: There are no tricks in plain and simple faith; but hollow men, like horses hot at hand, make gallant show and promise of their mettle; but when they should endure the bloody spur, they fall their crests, and, like deceitful jades, sink in the trial.

Cassius: Do not presume too much upon my love

Brutus: There is no terror, Cassius, in your threats; for I am arm’d so strong in honesty that they pass by me as the idle wind

Cassius: You do not love me. Brutus: I do not like your faults. Cassius: A friendly eye could never see such faults. Brutus: A flatterer’s would not, though they do appear as huge as high Olympus.

Cassius: Cassius is a weary of the world

Brutus: O that a man might know the end of this day’s business ere it come! But it sufficeth that the day will end, and then the end is known

Next Up: Antony and Cleopatra

The post Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: Or is it the Tragedy of Brutus? appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.