Michael J. Roueche's Blog, page 5

September 12, 2013

Announcing Historical Fiction “A River Divides,” sequel to “Beyond the Wood”

Historical fiction A River Divides is available in paperback and for Kindle and Nook.

We are pleased to announce the release of historical fiction A River Divides, Book Two of the Beyond the Wood Series. A River Divides continues the series’ focus on the Civil War, romance and adventure.

Thanks to Vesta House Publishing, NZ Graphics and everyone who’s helped put it together.

Both Cooke Fiction Award-winning Beyond the Wood and A River Divides are available for Kindle, the Nook at Barnes and Noble and in trade paperback.

If you like historical fiction, I hope you’ll take a look at both books, and if you like them, it would be great if you would do a review/rating for either or both on Amazon, Barnes and Noble and/or Goodreads. Positive reviews are immensely helpful and greatly appreciated.

If you want to know more about A River Divides or to peek at the first chapter, check out our books page.

The post Announcing Historical Fiction “A River Divides,” sequel to “Beyond the Wood” appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

On Sale: A River Divides, Beyond the Wood & More

A River Divides is now available in paperback and for Kindle and Nook.

We are excited to announce the release of A River Divides, Book Two of the Beyond the Wood Series.

Thank you to Vesta House Publishing, NZ Graphics and everyone who’s helped put it together.

A River Divides Available on Kindle for 99 Cents

To celebrate its release and to thank everyone for your support and patience, the kindle version of both Beyond the Wood and A River Divides will be on sale this weekend (September 13-16, 2013) for 99 cents each (usually $7.99).

Paperback versions are also available at slight discounts at Amazon, and you can buy both books for the Nook at Barnes and Noble.

If you like the books, it would be great if you would do a review/rating for either or both on Amazon and/or Goodreads. Positive reviews are immensely helpful and greatly appreciated.

If you want to know more about A River Divides or to peek at the first chapter, check out our books page.

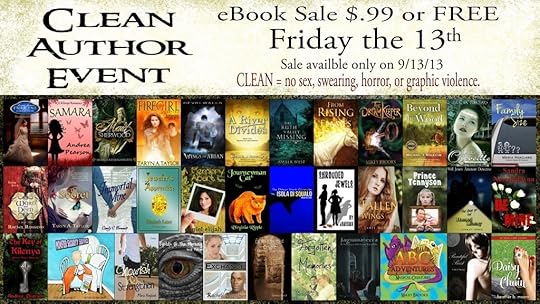

More Books on Sale at New Site Featuring “Clean” books

A new site promoting “clean” books has started and its authors are all offering books for free or 99 cents tomorrow, lucky Friday, September 13. If you’re interested, it’s a great time to pick up several:

The post On Sale: A River Divides, Beyond the Wood & More appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

September 10, 2013

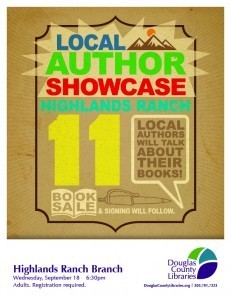

Join Me at Douglas County Libraries Local Author Showcase

Mark your calendars for Wednesday, September 18!

I’ll be at the Highlands Ranch branch library for the September Douglas County Libraries Local Author Showcase. I’ll join a handful of writers discussing their books. Each author will talk for up to five minutes about his or her book, and then we’ll visit and sign copies. I’m hoping to have early copies of A River Divides, sequel to Beyond the Wood, available that evening.

If you’re in the Denver area, drop by and say hi. Thanks for all the support.

Click on the poster below to visit Douglas County Libraries site to register and for information on authors coming and their books. The event is free, but I think for planning purposes they ask everyone to register. (Did I mention light refreshments?)

Thanks to Douglas County Libraries and Lisa Casper for continually looking for ways to support authors.

The post Join Me at Douglas County Libraries Local Author Showcase appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

September 4, 2013

Coriolanus: A Modern Political Tragedy Set in Rome

Coriolanus surprised me. When I began reading all of Shakespeare 16 months ago, I didn’t know the play existed. Now it’s a favorite.

Coriolanus decides, at the bidding of his mother, wife and son, to settle his dispute with Rome.

Why a favorite? Because it is so applicable to 21st Century politics, where people pit class against class, demonize opponents, conspire against political “enemies,” base their appeals on part truths or falsehoods and feed upon the ignorance and visceral tendencies of people. The play captures the vacillation of public opinion, the tragedy of seeking revenge and is a call for citizens to become informed about their respective governments. (I’ve just given away the play’s entire plot.)

Coriolanus is a condemnation of modern public dialogue, or perhaps it’s shows that politics is always the same, and that what we experience today—we complain that’s it’s particularly vile even as we sometimes actively participate in what makes it vile—is merely a constant of politics and the struggle for political dominance by party or faction.

The plays tells the story of a misunderstood “superhero” Caius Marcius, who is honored with the surname Coriolanus when he conquers for the Romans the Volscian city of Corioli. Perhaps you think my reference to superhero hyperbolic, but consider that the great Marcius leads the charge into the city. But the Volsci close the gate behind him, leaving him the lone Roman in town. But the marvelous Marcius emerges wounded, but alive, and leads a successful assault on Corioli. His heroism supercharges his men to victory.

A hero like that must be elected a consul of Rome, and his friends (nobles and senators) put him forward for this great honor. But, sadly, Coriolanus has little interest in behavior that would appeal to what he would call the rabble. Show them your wounds. Speak nicely to them. Such superficial action disgusts the returning hero. His unwillingness to “play” the customary election games opens the door to his enemies, the tribunes, to paint him as arrogant, haters of the citizens. The conflict rises till his perceived offenses are too great for the people, and they expel him from Rome.

But a superhero needs to be employed doing something, so he joins Rome’s enemies and leads them to the gates of Rome, in hopes of revenge upon the ungrateful city. There his mother convinces him to settle the situation peacefully. He is a hero now to the Volsci and retires with them to their city. But, once again, his political deafness, inability to control his tongue and plotting enemies create a confrontation that leads, via a preplanned plot, to his tragic and needfully quick (after all, he is a superhero) death.

Shakespeare wrote the play based on Plutarch’s recitation of a historical Coriolanus.

TS Eliot considered Coriolanus to be Shakespeare’s artistically best tragedy—better than Hamlet, King Lear, Othello. The play’s profile has been raised recently by a 2011 film version that edits the Bard and transports Coriolanus to a contemporary scene.

From me, Coriolanus earns five Bards:

Quotes I like (for various reasons):

Menenius: There was a time when all the body’s members rebell’d against the belly, thus accused it: That only like a gulf it did remain i’ the midst o’ the body, idle and unactive, still cupboarding the viand, never bearing like labour with the rest, where the other instruments did see and hear, devise, instruct, walk, feel, and, mutually participate, did minister unto the appetite and affection common of the whole body. . . . Your most grave belly was deliberate, not rash like his accusers, and thus answer’d: ‘True is it, my incorporate friends,’ quoth he, ‘That I receive the general food at first, which you do live upon; and fit it is, because I am the store-house and the shop of the whole body: but, if you do remember, I send it through the rivers of your blood, even to the court, the heart, to the seat o’ the brain; and, through the cranks and offices of man, the strongest nerves and small inferior veins from me receive that natural competency whereby they live: and though that all at once, you, my good friends,’–this says the belly, mark me,– ‘Though all at once cannot see what I do deliver out to each, yet I can make my audit up, that all from me do back receive the flour of all, and leave me but the bran.’

Marcius: He that will give good words to thee will flatter beneath abhorring.

1 Officer: To seem to affect the malice and displeasure of the people is as bad as that which he dislikes, to flatter them for their love.

3 Citizen: We have power in ourselves to do it, but it is a power that we have no power to do

3 Citizen: Ingratitude is monstrous, and for the multitude to be ingrateful, were to make a monster of the multitude

3 Citizen: We have been called [many-headed multitude] of many; not that our heads are some brown, some black, some auburn, some bald, but that our wits are so diversely coloured: and truly I think if all our wits were to issue out of one skull, they would fly east, west, north, south, and their consent of one direct way should be at once to all the points o’ the compass.

Coriolanus: Custom calls me to’t: What custom wills, in all things should we do’t, the dust on antique time would lie unswept, and mountainous error be too highly heapt for truth to o’er-peer.

Sicinius: To the Capitol, come: We will be there before the stream o’ the people; and this shall seem, as partly ’tis, their own, which we have goaded onward.

Coriolanus: Your dishonour mangles true judgment and bereaves the state of that integrity which should become’t, not having the power to do the good it would, for the in which doth control’t.

Menenius: His nature is too noble for the world: he would not flatter Neptune for his trident, or Jove for’s power to thunder.

Menenius: Do not cry havoc, where you should but hunt with modest warrant.

Coriolanus: Where is your ancient courage? you were used to say extremity was the trier of spirits; that common chances common men could bear; that when the sea was calm all boats alike show’d mastership in floating; fortune’s blows, when most struck home, being gentle wounded, craves a noble cunning: you were used to load me with precepts that would make invincible the heart that conn’d them.

Brutus: Now we have shown our power, let us seem humbler after it is done than when it was a-doing.

Volumnia: Anger’s my meat; I sup upon myself, and so shall starve with feeding.

Coriolanus: O world, thy slippery turns!

Aufidius: Pride, which out of daily fortune ever taints the happy man

Cominius: I minded him how royal ’twas to pardon when it was less expected

Coriolanus: I’ll never be such a gosling to obey instinct, but stand, as if a man were author of himself and knew no other kin.

Coriolanus: The end of war’s uncertain

(Quotes copied, capitalization changed August 28, 2013 from: http://shakespeare.mit.edu/coriolanus/full.html)

Next Up: Julius Caesar

The post Coriolanus: A Modern Political Tragedy Set in Rome appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

August 27, 2013

A River Divides: Preview the First Chapter

A River Divides, the sequel to award-winning Beyond the Wood, is scheduled for a mid-September release.

A River Divides, the sequel to award-winning Beyond the Wood, is scheduled for a mid-September release.

In anticipation of the release, we thought you might like to see the first chapter. We hope you enjoy it.

The action and romance of the Beyond the Wood continue:

It’s winter 1864. While Eastern Theater soldiers languish in camp boredom; conspiracy, treachery and mystery envelop Confederate widow Betsy Henderson. Is there something sinister in a visit from the town sheriff? Did she tell him too much? Can she be true to all she’s sworn?

In the meantime, William, a runaway slave, still craving his chance to fight for the Union, flees Virginia. Stumbling into the murky waters of Kentucky servitude and near death, he has nothing to offer but a worn body, exhausted spirit and troubled mind. Dare he imagine freedom, soldiering and even love? Or is he broken and fully spent?

In 1864, white and black, soldier and civilian, guilty and innocent are trapped in the tumultuous conflict, and nothing is as it seems.

Welcome to the river that divides them.

The post A River Divides: Preview the First Chapter appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

August 23, 2013

Another Shakespeare Blog Site & Sequel Preview

Last week I got an email for someone else who’s in the process of reading all of Shakespeare’s plays. I’ve added his interesting site to my list of Shakespeare resources, but also pass it along here: “Reading Shakespeare Plays.”

On the book front: We’ll be previewing the first chapter of A River Divides, sequel to Beyond the Wood, early next week here. Book is scheduled for release shortly. More details to come.

The post Another Shakespeare Blog Site & Sequel Preview appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

August 21, 2013

“That Big Black Dog”: Hero or Nero?

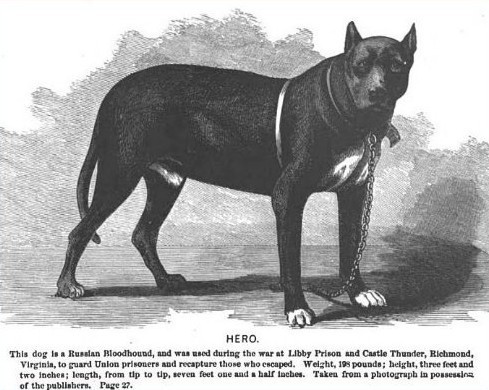

Disagreements, muddled facts and different perspectives are common when it comes to the Civil War. So it shouldn’t surprise anyone that getting accurate facts on Nero, one of the war’s most famous or infamous dogs, is impossible. Nero was a canine guard at Richmond’s Castle Thunder prison, a facility for traitors, escaped slaves and Confederate deserters. He also helped later in the war at Libby Prison, where Union officers were imprisoned.

What was he really called? What breed was he? Was he vicious or gentle and loving? The answers depend on who’s telling the story.

Nero’s Biography

His biography is sketchy. In the preface to a Richmond Dispatch article that appeared 30 years after the war, the correspondent wrote, “Since the war I have seen many accounts published in our papers about him, all of which, in some particulars, were incorrect.” Here’s what the Dispatch assured us was Nero’s authentic story:

Some time in 1859 or 1860 he was brought to Richmond, a puppy, by the captain of a Bavarian vessel which landed at Rocketts. The captain gave the puppy to Mr. John Allen, of the firm of Ginter & Allen. Mr. Allen gave him to Mr. James Lyons. Mr. Lyons allowed Joe Mayo, the Mayor of the city, to take him and keep him in the city jail, as a sort of guard, because he was too large and ferocious-looking to be permitted to go at large. When Captain [George W.] Alexander [first commandant of Castle Thunder] came to Richmond, he saw Nero in the city jail and was greatly struck at his size and beauty. He persuaded Mr. Mayo, with Mr. Lyon’s consent, to allow him to take Nero to Castle Thunder, and there he remained until the close of the war.1

Nero’s Breed

Nero was massive, reportedly weighing about 200 pounds, measuring 38 inches high (See accompanying illustration caption) and “about seven feet in length from tip to top.”2 He was a Bavarian boarhound,1 or a bloodhound,3 or a Russian bloodhound,4 or a splendid cross between a Russian bloodhound and a bull-dog.2 In short, he was something like the ancestor of the modern Great Dane.

Nero was massive, reportedly weighing about 200 pounds, measuring 38 inches high (See accompanying illustration caption) and “about seven feet in length from tip to top.”2 He was a Bavarian boarhound,1 or a bloodhound,3 or a Russian bloodhound,4 or a splendid cross between a Russian bloodhound and a bull-dog.2 In short, he was something like the ancestor of the modern Great Dane.

Nero’s real name?

Good question. He’s listed either as Nero or Hero, perhaps depending on the geographical preferences of the person calling him.

A Sweet Temperament?

Reports of his temperament differ substantially.

The Richmond dispatch gets both versions in their 1895 story:

Visitors at the Castle were amazed at him, and their spontaneous exclamations at sight of him would be: “Goodness! What a splendid dog!” He was permitted to run about the Castle as he pleased, and was a great favorite with the prisoners. Ordinarily he was good natured, playful, and docile, but when angered or provoked he was terrible looking, and dangerous. I have seen Captain Alexander whip him with a horsewhip, at the same time have a cocked revolver in his other hand, which occasionally he would fire over his head, and then he appeared the very impersonation of ferocity subdued by the will of man.1

Union prisoner George Haven Putnam’s can’t report any good-natured interaction with Nero:

I had trouble with that dog some months later when I was on parole in Richmond. I had been told that the intelligence of the blood hound enabled him to be taught all kinds of things, but that it was very difficult, if not impossible, to unteach him anything. This hound had been taught “to go for” anybody wearing blue cloth. At this later time, I had secured clean clothes from home and the blue was, therefore, really blue instead of the nondescript colour of my much-worn prison garments. I had occasion from time to time to go to Castle Thunder, where the dog was kept, and the sergeant of the prison guard amused himself by putting the dog on a long leash to see how near he could get to the little Yankee adjutant without quite “chawing” him up. I complained in due form to the captain of the guard that the jaws of the hound did not constitute a fair war risk. He accepted my view and had the dog put on a shorter leash so that I was able to get past him into the prison door.3

The Richmond Whig also didn’t see Nero’s kinder, reporting “We have seen him seize little dogs that came around his heels, shake them and cast them twenty feet from him. The stoutest man he would bring to the ground by one gripe on the throat, and it was always a difficult matter to get him off if he had once tasted or smelled blood.”2

As for his courage and ferocity around little dogs, the Reverend J. L. Burrows, D.D. holds a slightly different opinion:

[The] commandant of Castle Thunder, had generally at his heels “the monstrous savage Russian bloodhound” as he was very unjustly stigmatized by the Federal soldiers . . . as a specimen of the cruel devices of Southern officials to worry and torture prisoners.

There was absolutely nothing formidable about the dog but his size, which was immense. He was one of the best-natured hounds whose head I ever patted, and one of the most cowardly. If a fise [i.e., small dog] or a black-and-tan terrier barked at him as he stood majestic in the office-door, he would tuck his tail between his legs and skulk for a safer [place], and he was quite a playfellow with the prisoners when permitted to stalk among them.5

But paroled prisoner Putnam’s account of having to control him with a leash doesn’t square with J. Marshall Hannah’s account:

The constant attendant upon the commandant, lying at his feet, walking at his side, or ranging through the Castle, with the entrée of every quarter, was “Hero,” the Russian bloodhound, of massive size, terrible appearance, but peaceful in disposition. He acted only upon orders from his master, but then that action was quick as a thunderbolt. The person of the commandant was perfectly secure in his company, though he was unarmed.

The sagacity of Hero seemed to partake of the military character, and he fell readily into the routine of the Post. At the drum beat for parade in the guard room for mustering relief, Hero would walk through the gang-way, pausing for the sentinel to remove his musket, and leisurely ascend the stairway to the guard room. There he would seat himself on his haunches, and calmly observe the evolutions of the guard. Some of the guard on coming to a “present arms,” would pretend to salute Hero; whereat the dog would express delight, nod and yawn, as though he comprehended the movement, which doubtless he did, after a dog’s fashion. The parade over, Hero would descend to the great prison room, and attend the roll call of the prisoners, manifesting the same degree of interest.

In this way Hero inspected all the operations of the Castle, penetrating to the cook room and mess room, but never touching anything unless given him from the hand of the Commandant. He was afraid of being poisoned by some of the prisoners who were enemies to his master, and therefore kept upon his guard, eating his daily rations of raw beef and bread, prepared by his master.4

He was also strikingly loyal. The Richmond Whig described the escape of four prisoners. During the escape a guard was killed, and the newspaper noted:

A singular incident occurred, when a crowd of soldiers on duty at the prison, collected around the body after the murder. A well known large dog, belonging to Capt. Alexander, placed himself beside the body, and would allow no one to approach until the proper officer relieved him of the charge; and then followed the corpse into the building. This exhibition of canine affection was as touching as it is remarkable.6

What Ever Happened to Nero?

The real answer to this question is no one knows.

Varying ends to his story exist, including supposition by the Whig that he left Richmond with Jefferson Davis. But the paper quickly retracted, noting:

From a personal dog paragraph in a Northern paper, we perceive that Hero has arrived in the vicinity of Washington, and was quite a hero indeed. Mr. Munn, sutler of the 140thNew York regiment, captured him in Richmond, and sent him North, a prisoner of war. …Hero was a “rebel” dog during all the days of the rebellion, but we learn he has taken a fancy to his captors, and is trying to be a good, loyal, Union dog.

Hero in Richmond, was an official, stern-looking dog, and he was as well known as any of the crabbed officials themselves, and was respected accordingly. His old acquaintances will be glad to hear that his dogship has the prospect of an engagement for exhibition. Some menagerie, or Barnum will get him.2

It sounds like a somewhat happy ending, but like a play, movie or book that offers alternative endings, the Richmond Dispatch carried a different end:

After the city fell into the hands of the Federal troops and Castle Thunder was vacated, Nero took up his abode with Mr. Stephen Childrey, who had been commissary of the prison, and while there had generally had him fed. Some time in the summer of 1865 some Yankees took the dog and carried him through the Northern States and exhibited him as a show to the people. Flaming advertisements were posted about him. He was said to be the dog which was kept at Libby Prison to eat Yankee prisoners, and his qualities, disposition, and immense size were set forth in grandiloquent style. This, of course, attracted public attention, and much money was realized from his exhibition. Mr. Childrey, who accompanied him on this northern tour, returned home six months thereafter and he told me that his share of the profits was $3,000.1

But no matter what happened to “that big black dog,” he was loyal to Castle Thunder to the end, serving under three different commandants. Even if you can’t figure out what Nero was like, can’t you just see his first commandant, Captain George W. Alexander, in “tight-fitting suit of black trousers, buckled at the knees; his black stockings and black loose shirt, relieved only by a white collar, with his long, black whiskers flowing in the wind, riding at full gallop on his black horse along [Richmond] streets, with his large, magnificent black dog Nero following at his heels.”1

Or was it Hero at his heels?

Sources:

1. “Old Castle Thunder,” Richmond Dispatch, March 31, 1895, retrieved August 20, 2013 from Michael D. Gorman, Civil War Richmond, http://www.mdgorman.com/Written_Accounts/Dispatch/Postwar/richmond_dispatch_331895.htm

2. “That Big Black Dog Again,” Richmond Whig, May 19th, 1865, retrieved August 20, 2013 from Michael D. Gorman, Civil War Richmond, http://www.mdgorman.com/Written_Accounts/Whig/1865/richmond_whig_5191865.htm

3. “A Prisoner of War in Virginia 1864-65,” George Haven Putnam, G.P Putnam’s Sons, New York and London, The Knickerbocker Press, 1912, pp. 28-29, retrieved August 20, 2013 from http://books.google.com/books/about/A_prisoner_of_war_in_Virginia_1864_5.html?id=nipCAAAAIAAJ

4. “Castle Thunder in Bellum Days”, BY J. MARSHALL HANNA, Southern Opinion, November 11, 1867, retrieved August 20, 2013 from Michael D. Gorman, Civil War Richmond, http://www.mdgorman.com/Written_Accounts/Other_Papers/southern_opinion,_11_23_1867.htm

5. “Recollection of Libby Prison,” Rev. J. L. Burrows, D.D., Read before the Louisville Southern Historical Association. Retrieved August 20, 2013 from Ancestory.com, http://homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~jladd/stories/libby02.htm

6. “Escape of Prisoners–Sentinel Killed,” Richmond Whig, October 23, 1863, retrieved August 20, 2013 from Michael D. Gorman, Civil War Richmond, http://mdgorman.com/Written_Accounts/Whig/1863/richmond_whig,_10_23_1863.htm

The post “That Big Black Dog”: Hero or Nero? appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

August 19, 2013

Shakespeare’s Rich Satire: Timon of Athens

Timon of Athens shares his wealth unthinkingly, before bankrupting himself with generosity.

As I finish reading Timon of Athens, I find myself in conundrum. Every list I’ve read includes the play among Shakespeare’s tragedies. But it didn’t feel tragic, because I never felt Timon was a real person. He felt more like a character created to embody the play’s message, overplaying his flip from naively generous patron and friend to cynic and humankind hater. I felt no sorrow at his death as it seemed an inevitable conclusion to the play’s theme and his role in it. From where I read it, Timon of Athens (both the play and the character) is satirical, comic, sarcastic, cynical, ironical and surprisingly entertaining. (Can I include all those attributes in one sentence?)

As the play begins, Timon of Athens, with his generous nature, is friend to everyone: the needy, the indebted, the powerful, the artistic. One exception to his love of mankind is the cynical and humankind hating philosopher Apemantus. In Timon’s excessive generosity, he unthinkingly spends his prosperity on others, till nothing is left. But the men he has treated so well forget his kindnesses and turn on him, demanding payment for money he owes. The generous-hearted Timon transforms at light speed into just another form of Apemantus, condemning all men (still including Apemantus) and exiling himself to the woods to live alone.

There the irony: Timon no-long-of-Athens finds gold, enough to reestablish himself at the top of Athenian society. But he rejects the gold and society and is happy to rid himself of his new-found wealth by tossing it at or to anyone who passes nearby—army general and mistresses, thieves, poet and painter.

But Athens is under threat from attack, and it turns to Timon for succor because the attacking general is loyal to Timon. Timon rejects the city’s pleas vilely, and it falls.

Shakespeare wrote the words that capture the theme of Timon of Athens for me and put in the mouth of the poet who visits the self-exiled Timon offering—in hopes of a share of the gold—to write a poem that “must be a personating of ” [Timon]. It will be “satire against the softness of prosperity, with a discovery of the infinite flatteries that follow youth and opulency.”

It’s the gnat principle. Gnats of the sort found in Virginia, swarm around any human head they can find (animals, too). Wealth and influence likewise attracts other men and women. In hope of benefiting from that wealth and influence, they swarm like gnats about whoever possesses it. As with Timon, when the wealth, influence or prominence fail, the swarms of humans disappear.

What can I do for my fellow seems much harder to think and act on, than the opposite: what can I gain from my fellow.

I like the message so much, even though the getting there seems a little contrived and bitter, that I’m giving Timon of Athens four bards:

Quotes I like (for various reasons) from Timon of Athens:

Poet: When we for recompense have prais’d the vile, it stains the glory in that happy verse which aptly sings the good.

Poet: His large fortune, upon his good and gracious nature hanging, subdues and properties to his love and tenderance all sorts of hearts

Poet: All those which were his fellows but of late,—Some better than his value,—on the moment follow his strides, his lobbies fill with tendance, rain sacrificial whisperings in his ear, make sacred even his stirrup, and through him drink the free air.

Poet: When Fortune, in her shift and change of mood, spurns down her late belov’d, all his dependents, which labour’d after him to the mountain’s top, even on their knees and hands, let him slip down, not one accompanying his declining foot.

Apemantus: He that loves to be flattered is worthy o’ the flatterer.

1st Lord: What time o’ day is’t, Apemantus? Apemantus: Time to be honest.

Timon: There’s none can truly say he gives if he receives

Apemantus: It grieves me to see so many dip their meat in one man’s blood; and all the madness is, he cheers them up too. I wonder men dare trust themselves with men: Methinks they should invite them without knives; good for their meat and safer for their lives.

Apemantus: The fellow that sits next him now, parts bread with him, pledges the breadth of him in a divided draught, is the readiest man to kill him: ‘t has been prov’d.

Timon: What need we have any friends if we should ne’er have need of ‘em? They were the most needless creatures living, should we ne’er have use for ‘em; and would most resemble sweet instruments hung up in cases, that keep their sounds to themselves.

Timon: We are born to do benefits: and what better or properer can we call our own than the riches of our friends?

Apemantus: Like madness is the glory of this life.

Apemantus: I, should fear those that dance before me now would one day stamp upon me: ‘t has been done; men shut their doors against a setting sun.

Timon: Methinks I could deal kingdoms to my friends, and ne’er be weary.

Apemantus: I’ll nothing, for if I should be bribed too, there would be none left to rail upon thee; and then thou wouldst sin the faster. Thou givest so long, Timon, I fear me thou wilt give away thyself in paper shortly: what need these feasts, pomps, and vain glories?

Flavius: When the means are gone that buy this praise the breath is gone whereof this praise is made: Feast-won, fast-lost

Timon: Unwisely, not ignobly, have I given.

1 Stranger: O See the monstrousness of man when he looks out in an ungrateful shape!

2nd Servant of Varro: Who can speak broader than he that has no house to put his head in? Such may rail against great buildings.

1st Senator: He’s truly valiant that can wisely suffer the worst that man can breathe; and make his wrongs his outsides,—to wear them like his raiment carelessly; and ne’er prefer his injuries to his heart, to bring it into danger.

1st Senator: You cannot make gross sins look clear: to revenge is no valour, but to bear.

2nd Senator: He has a sin that often drowns him, and takes his valour prisoner: If there were no foes, that were enough to overcome him.

4th Lord: One day he gives us diamonds, next day stones.

Timon: Lust and liberty creep in the minds and marrows of our youth, that ‘gainst the stream of virtue they may strive and drown themselves in rot!

Flavius: We have seen better days.

Flavius: Who would not wish to be from wealth exempt since riches point to misery and contempt?

Flavius: Bounty, that makes gods, does still mar men.

Timon: Gold? Yellow glittering, precious gold? …Will make black, white; foul, fair; wrong, right; base, noble; old, young; coward, valiant. …[Gold] will lug your priests and servants from your sides; pluck stout men’s pillows from below their heads: this yellow slave will knit and break religions; bless the accurs’d; make the hoar leprosy ador’d; place thieves; and give them title, knee, and approbation, with senators on the bench: this is it that makes the wappen’d widow wed again; she whom the spital-house and ulcerous sores would cast the gorge at, this embalms and spices to the April day again.

Phrynia and Timandra: Believe ‘t, that we’ll do anything for gold.

Apemantus: Seek to thrive by that which has undone thee: hinge they knee, and let his very breath whom thou ‘lt observe blow off thy cap; praise his most vicious strain and call it excellent

Timon: I am sick of this false world; and will love naught but even the mere necessities upon ‘t.

1st Thief: We cannot live on grass, on berries, water, as beasts and birds and fishes. Timon: Nor on the beasts themselves, the birds, and fishes; you must eat men. Yet thanks I must you con, that you are thieves profess’d; that you work not in holier shapes; for there is boundless theft in limited professions.

Timon: The sun’s a thief, and with his great attraction robs the vast sea: the moon’s an arrant thief, and her pale fire she snatches from the sun: the sea’s a thief, whose liquid surge resolves the moon into salt tears: the earth’s a thief, that feeds and breeds by a composture stolen from general excrement; each thing’s a thief

Timon: Many so arrive at second masters upon their first lord’s neck.

1st Senator: Crimes, like lands, are not inherited.

Up Next: Coriolanus

The post Shakespeare’s Rich Satire: Timon of Athens appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

August 1, 2013

Troilus and Cressida: It Gave Pander a Bad Name

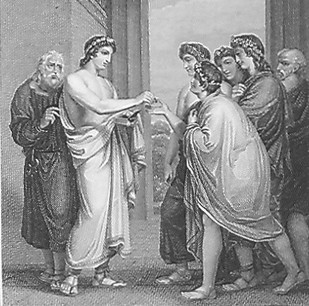

Troilus witnesses Cressida betraying their sworn love in Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, act v, scene ii. Engraving by Luigi Schiavonetti from painting by Angelica Kauffmann.

Shakespeare did not create the love story of heroic Troilus and unfaithful Cressida. Troilus and Cressida as delivered to and by Shakespeare has a long, complicated pedigree.

According to Karl Young in The Origin of Troilus and Criseyde, the couple’s romance dates to Le Roman de Troie, a poem about the fall of Troy written by Benoît de Sainte-Maure, a Frenchman living at the time of and in the continental lands of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. He didn’t make up the characters, but Sainte-Maure conjured the tragic love.

Next to chronicle and alter the story was Italian Giovanni Boccaccio in his poem Il Filostrato, and his account influenced Chaucer’s version, Troilus and Criseyde. Shakespeare got the story from Chaucer and altered and darkened it.

Trying to classify this play evidently is problematic, but it looks easy to me: It’s tragedy, and not a great one at that. The end is dissatisfying. As far as I can tell, the biggest contribution of the story of Troilus and Cressida (even before Shakespeare) was to add a troublesome word to our vocabulary: panderer. It comes from the role Cressida’s uncle, Pandarus, plays in bringing the couple together for one night.

Troilus and Cressida is set in the final days of Troy. When the plays begins, Cressida’s father, seeing Troy’s coming doom, has already defected to the Greeks, leaving his daughter—conveniently for the story—behind. Apparently disloyalty is a family trait.

The mighty Trojan Hector is busy challenging the Greeks to send their best fighter to take him on. The Greek’s greatest fighter, Achilles, is refusing to come out of his tent to fight, smitten by love of his own reputation and deeds and seemingly in the middle of a one-man work stoppage.

Troilus, Hector’s brave brother, is smitten by the second most beautiful woman in Troy (and maybe she’s more lovely than the renowned Helen). Cressida is attracted to Troilus, and Pandarus brings the couple together. Cressida swears loyalty, ever-lasting love, etc. to Troilus, but they wake to learn the Greeks have offered a swap, trading captive and great Trojan general Antenor for Cressida. The very agent, Diomedes, sent to bring Cressida to the Greeks seduces Cressida, who falls amazingly quickly. Shakespeare makes sure Troilus witnesses her disloyalty with his own eyes.

The question that is never adequately answered is why Cressida does what she does. She seems a pawn of the men around her and the cause of what they do. Helen plays the same role in the larger story of the Trojan War. Both women are merely objects to worship, to covet, to win. Yet it is clear from dialogue that both women are intelligent, witty, cleaver.

Shakespeare gives us no resolving justice to Cressida’s disloyalty, and to add to the play’s acrid flavor, Achilles finally comes out of his tent and kills Hector, not in brave fair battle, but by sending in his skillful, loyal Myrmidon to kill an unarmed Hector, while Achilles watches in safety. Achilles claims “the kill” and desecrates the Trojan’s body, all of this foreshadowing the coming fall of Troy.

Cynical and misogynistic might best ways to describe this play. Instead of love that endures separation and hardship, instead of heroic battle, Shakespeare gives us sworn love easily surrendered and anticlimactic and anti-heroic battle death. The play seems to be pro-Troy (maybe that’s just because it lost the war), against pride and mocks bravery, courage and classical Greek and Trojan legends.

I could have passed on reading Troilus and Cressida. I’m classifying it as a tragedy play—the first I’ve read in my quest to read all of Shakespeare by the Bard’s 450th birthday—and I’m giving it one Bard:

Quotes I like (for various reasons):

Pandarus: He that will have a cake out of the wheat must needs tarry the grinding.

Agamemnon: Call them shames, which are, indeed, naught else but the protractive trials of great Jove to find persistive constancy in men?

Nestor: In the reproof of chance lies the true proof of men

Nestor: Even so doth valour’s show and valour’s worth divide in storms of fortune

Ulysses: Then everything includes itself in power, power into will, will into appetite; and appetite, an universal wolf, so doubly seconded with will and power, must make perforce an universal prey, and last eat up himself, …this chaos, when degree is suffocate, follows the choking.

Hector: Modest doubt is call’d the beacon of the wise

Hector: ‘Tis mad idolatry to make the service greater than the god

Troilus: We turn not back the silks upon the merchant when we have soil’d them

Troilus: Is she [Helen] worth keeping? Why, she is a pearl, whose price hath launch’d above a thousand ships and turn’d crown’d kings to merchants.

Ulysses: The amity that wisdom knits not, folly may easily untie.

Ajax: Why should a man be proud? How doth pride grow?

Agamemnon: He that is proud eats up himself: pride is his own glass, his own trumpet, his own chronicle; and whatever praises itself but in the deed devours the deed in praise.

Ajax: I hate a proud man as I hate the engendering of toads.

Ulysses: He is so plaguy proud that the death of it tokens cry, No recovery.

Pandarus: Fair be to you, …and to all this fair company! Fair desires, in all fair measure, fairly guide them!—especially to you, fair queen! Fair thoughts be your fair pillow! Helen: Dear lord, you are full of fair words.

Pandarus: Sweet queen, sweet queen; that’s a sweet queen, I’ faith. Helen: And to make a sweet lady sad is a sour offence.

Helen: Let thy song be love: this love will undo us all.

Troilus: I am giddy; expectation whirls me round. The imaginary relish is so sweet that it enchants my sense: what will it be, when that the wat’ry palate tastes indeed love’s thrice-repured nectar? Death, I fear me; swooning destruction; or some joy too fine, too subtle-potent, tun’d too sharp in sweetness, for the capacity of my ruder powers; I fear it much

Pandarus: Words pay no debts, give her deeds

Troilus: Fears make devils of cherubims; they never see truly.

Cressida: They that have the voice of lions and the act of hares, are they not monsters?

Cressida: Where is my wit? I know not what I speak.

Ulysses: Pride hath no other glass to show itself but pride

Achilles: Not a man, for being simply man, hath any honour; but honour for those honours that are without him as place, riches, and favour, prizes of accident as oft as merit: which when they fall, as being slippery standers, the love that lean’d on them as slippery too, do one pluck down another, and together die in the fall.

Ulysses: Those scraps are good deeds past; which are devour’d as fast as they are made, forgot as soon as done: perseverance, dear my lord, keeps honour bright: to have done is to hang quite out of fashion, like a rusty mail in monumental mockery.

Patroclus: Those wounds heal ill that men do give themselves

Thersites: A plague of opinion!

Troilus: Sometimes we are devils to ourselves, when we will tempt the frailty of our powers, presuming on their changeful potency.

Thersites: Thou picture of what thou seemest, and idol of idiot worshippers

Cressida: Minds sway’d by eyes are full of turpitude.

Thersites: Lechery, lechery; still wars and lechery; nothing else holds fashion

Andromache: Do not count it holy to hurt by being just: it is as lawful, for we would give much, to use violent thefts, and rob in the behalf of charity.

Hector: Life every man holds dear, but the dear man holds honour far more precious dear than life.

Finally, Cressida and Pandarus proclaim their own destinies:

Cressida: If I be false, or swerve a hair from truth, when time is old and hath forgot itself, when waterdrops have worn the stones of Troy, and blind oblivion swallow’d cities up, and mighty states characterless are grated to dusty nothing; yet let memory from false to false, among false maids in love, upbraid my falsehood! When they have have said—as false as air, as water, wind, or sandy earth, as fox to lamb, as wolf to heifer’s calf, pard to the hind, or stepdame to her son; yea, let them say, to stick the heart of falsehood, as false as Cressid.

Pandarus: Go to, a bargain made: seal it, seal it; I’ll be the witness. Here I hold your hand; here my cousin’s. If ever you prove false one to another, since I have taken such pains to bring you together, let all pitiful goers-between be called to the world’s end after my name, call them all Pandars; let all constant men be Troiluses, all false women Cressids, and all brokers between Pandars!

Next Up: Timon of Athens

The post appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.

July 24, 2013

Lincoln: A great film, great acting, but why the historical flubs?

David Strathairn played Secretary William Seward so well that I can almost see him in place of the real Seward sitting across from Lincoln in Francis Bicknell Carpenter’s painting the First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation.

I finally watched Steven Spielberg’s wonderful movie about Lincoln (not exactly timely, but that’s ok). I had been looking forward to seeing it since it came out late last year, and it was worth the wait.

I’d heard it was based on Doris Kearns‘ insightful Team of Rivals, one of my favorite books about the Civil War era. After seeing the movie I noticed someone wrote the book was—and I agree with it—more the “jumping off point” for the movie. The movie is focused for the most part on such a short period of time and on one element of the era—the passage of the 13th Amendment. The vast, vast majority of the story Kearns captured simply isn’t addressed and would not have fit anyway. Perhaps dependence of the film on the book also relates to capturing the characters and personalities of Lincoln, Secretary of State William Seward and others.

I enjoyed the movie immensely. ‘ Oscar-winning performance as Lincoln was superb, amazing. I could not have imagined a better portrayal and am left hoping that Lincoln the man was like the Day-Lewis’ portrayal. was great in her role as Mary Todd Lincoln. as Secretary Seward was so convincing that I think it’s him I now see—rather than the real Seward—in the often used picture of Lincoln’s cabinet during the first reading of the Emancipation Proclamation–a version of the picture appears on the cover of Team of Rivals. was wonderful as Senator Thaddeus Stevens. While the whole production had a marvelous feel to it, the acting was the highlight, and the fact that there were so many strong performances allowed Day-Lewis’ Lincoln to shine without overwhelming the production.

The film is not fast paced or action filled, and I appreciated Spielberg’s courage in presenting complex ideas and issues in dialogue (Were the states in rebellion or another country? One interpretation was required to enact the Emancipation Proclamation, another required to accept a peace delegation from the Confederacy.) Because of its subtle conceptual dialogue, I plan to watch it again. The Lincoln filmmakers also are leading by presenting, according to Philip Zelikow, professor of history at the University of Virginia, in a New York Times Disunion column, a new perspective on history.

Now that I’ve registered all that praise, here is my not-insignificant problem with the film. For a film so long in development, with as many resources available as it had, and with its feeling of almost documentary precision, I was disappointed by the historical errors in the film. I appreciate that history is difficult to get right, and perhaps with ever-existing differing perspectives of the Civil War, it is particularly hard to capture the era accurately, and I acknowledge that some errors were insignificant (some I probably didn’t even recognize). However some were keenly important and none of them were necessary. If they’d made them in ignorance, I could accept that, but I suspect those involved knew exactly where they were being inaccurate.

When challenged on one historical inaccuracy in Lincoln, the writer, Tony Kushner wrote sarcastically, “I hope nobody is shocked to learn that I also made up dialogue and imagined encounters and invented characters.” But that’s subterfuge. Creating dialogue and encounters where we have no witnesses is acceptable, ignoring well-known historical facts is deceptive in a film that seems to present itself as capturing history. Odd that neither he nor Spielberg understood that.

Important also is the reality that as fewer and fewer people study history, more and more people will get their education in history from Hollywood. Frightening. The serious, seemingly historical approach this film took called for historical accuracy. For no apparent reason, they didn’t measure up to that challenge. Numerous columns and blogs have been written covering the inaccuracies, appearing at such sites as The Daily Beast, Slate, Yahoo, New Yorker, LA Times.

Particularly irksome for me was the well-scrubbed view of freedmen. The seemingly sudden total acceptance of black soldiers and a parade of freedmen pouring into the Senate Chamber apparently for the “first time” comes out of nowhere. Most egregious is the scene where black troops “welcome” a peace delegation from the Confederacy. What follows is not hyperbole: Imagining blacks troops being assigned to “welcome” the Confederate delegation when it arrives for negotiations is like the Allies in World War II sending a Jewish delegation to negotiate peace with Nazi Germany. It feels great (think Rudy), it feels like justice (but isn’t reality), but it would not have happened, would not been effective diplomacy and would not have moved the Confederacy closer to laying down their arms/rejoining the Union. Such easy solutions are not real and do real injustice to:

the struggles and efforts of slaves, freedmen and members of the army’s “sable arm”

the challenges brought by Reconstruction

the discrimination of the Post-Reconstruction era

and the mid-20th century fight for Civil Rights.

It is bad history and a bad lesson to teach aspiring leaders and diplomats.

My last observation on Lincoln is that the end of the film seems useless, cheap and a distraction. It would have been better to shorten the film by five minutes. (Although I do always like hearing the Second Inaugural Address.)

With praise for and concerns about Spielberg’s film Lincoln, I’m looking forward to watching it again.

The post Lincoln: A great film, great acting, but why the historical flubs? appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.