An Amazing, Inspiring Elmira Prison Story and a Question

Confederate Lieutenant J. M. Waddill gives canteen to injured Union soldier during 1864 Wilderness Battle. Illustration taken from 1896 edition of Under Both Flags.

Confederate Lieutenant J. M. Waddill tells a story that begins May 5, 1864k in the middle of the Civil War’s Wilderness Battle.¹

In that battle, his unit lost its captain and first lieutenant, leaving Waddill in command. He was ordered to move his men to the rear, where they were charged with protecting a wagon train from an anticipated enemy cavalry raid, which never came.

While they waited, he heard a groan several times from a nearby thicket, and investigating, he found “30 or 40 steps from the road, in a perfect tangle of brush and vines” a young, wounded Union soldier lying face down. He gently rolled him over, expecting to find he had expired. But he was still alive. The youth had been injured in the hip and Waddill gave him his canteen, visited with him—a soldier of the 5th New York Cavalry—gave him bacon and bread. Most importantly, as there was a fire blazing nearby in woods, the lieutenant cleared away brush, tangle, leaves and rubbish from around the lad to save him from a horrible death. After making him as comfortable as possible, Waddill bid the boy goodbye, “promising to see him again, went back to [his] company.”

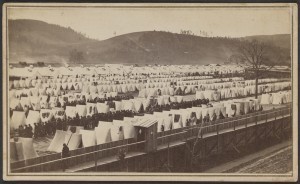

Waddill forgot the incident as he fought on during the bloody summer of ’64 in Virginia. Unfortunately, he was taken prison at Hanover. Virginia, and marched to a new prison camp in Elmira, New York. Although there was no way he would have known, Elmira, nicknamed “Hellmira” by prisoners, would have during its brief 15-month duration the highest death rate—more than 24% among the 12,000 plus soldiers incarcerated there—of any Northern prisoner of war camp.² Twenty-seven years later when he wrote his account, Waddill describes his circumstances at Elmira as merely, “My circumstances and surroundings at Elmira were not of a joyful nature. Discipline was strict, and the days were remarkably alike.” The monotony was broken by visitors from the local community who came to see the prisoners, ask them questions and give prisoners small gifts.

Elmira Prison Camp in Upstate New York had the highest death rate of any Union prison during the Civil War.

One day an older lady accompanied by an attractive younger woman visited the Elmira camp. They stopped to visit Waddill briefly, asking his name and rank and if he needed anything. They wished him a “speedy return to [his] friends” as they continued on after their brief interview.

The same women came several days later and visited with him more earnestly, asking about prison and army life. As they left, the younger lady slipped him a small New Testament. He opened it, hoping to find his lovely benefactor’s name. Instead he found a note on the fly-leaf: “Would you place yourself in the hands of a friend, and assume the attendant risks? If so, tie a bit of white cord to the bottom button of your coat, when we come next week. Confide in no one else, and destroy this.” He immediately tore out the note and “chewed it into pulp.”

The lieutenant spent the night wondering and weighing his options. Why did they want to help him, and “was it a trap?” By morning he had decided to “trust them fully.” When his visitors came again and saw the meaningful white cord, the young woman gave him a “religious tract, and, with a most indifferent, unconcerned look, passed on.” When he next found himself alone, he opened the tract and found another handwritten note:

Two weeks from this date, a woman, with a red-bordered handkerchief in her belt, will give you a thin linen coast and vest. Carry them to your quarters, conceal them, and return immediately. An old man, with gold eyeglasses, will give you pants, shoes, and collar. Do likewise with these and return. We will give you a hat, in the lining of which will be found a permit, signed by the Commandant, allowing Mr. William J. Pool, of Syracuse, to visit the prisoners. As soon as possible without exciting attention, put on your new suit and walk quietly to the exit, surrendering your permit to the guard. When outside, walk slowly, straight away from the prison for two hundred paces, when a young man will meet you. Trust yourself to him, and confide in no one else. Should anything transpire endangering you or us, cut the two bottom buttons from your coat.

The days crept by, but the day finally came and, as described, he was given the promised clothes, with his young friend lastly tossing him a hat, saying, “Here’s a Yankee hat from a Yankee girl. Will a rebel accept it?” “No, Miss,” Waddill responded, “but a Southern gentleman will.”

Once he had his complete civilian wardrobe, quick moments of doubt and hesitation followed, but he wrestled and conquered his concern and acted immediately. Dressing in his new attire, Waddill approached Elmira’s gate hoping it was his last impediment to hoped-for freedom. But a fellow prisoner recognized him and was about to talk to him, when Waddill—I suspect in desperation—pulled his knife from his pocket and said loudly, to be heard of the guard, “’Here reb, take this to cut your beef with,’ adding in a whisper, ‘For God’s sake, say nothing.’” The last minute-ruse worked, and the lieutenant surrendered his pass to the guard and walked freely through the gates.

He was met shortly by a young Avery Chauncey who took him to his father’s home and hid him from visitors, searchers and the servants in a 6-by-8-foot hidden room he and his father had created between a wall and sloping rafters. Avery, as it turned out, was the brother to the young woman who had befriended him.

The Chauncey’s hid their Confederate escapee, expecting an Elmira-wide search for the missing soldier. But, it appeared the prison administrators never missed Waddill, and he was soon invited down each evening to visit with the family, especially with Esther, the young woman whom he had first met in the prison, with whom he had grown very attached. He confessed his love for her, which fortunately was matched by her affection for the Southern gentleman. It was at that point he learned she had been the family member who had chosen him for saving:

“So it was you who selected me from among the hundreds as the object of your most disloyal intentions,” he announced.

“Yes; we looked carefully over the entire collection,” she answered…”and I decided that you should be the favored one’….”

“And why, pray, was I selected?…”

“We never told you the story, did we?…”Last spring, brother Avery was badly, wounded down in Virginia. A rebel—I mean a Confederate—officer was very good to him, giving him food and water, and protecting him from a fire which would soon have burned him to death. When he was able to move we brought him home, and he often said that when he recovered he would return the kindness to some Southerner. He has never regained his strength sufficiently to return to the army, so he decided to pay his debt by releasing one of the prisoners, all of us promising to help him. The selection of the victim was left to me, and I thought you—you looked—nice, and I felt more sorry for you than any of the others….”

When Waddill realized and confessed he had been Avery’s savior, Avery—who had always thought Waddill looked familiar—finally recognized him. The story ends with Esther marrying her Rebel lieutenant and Elmira-survivor after the war, as Waddill returned to Lee’s army to fight from Petersburg to the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse. The Waddill’s then moved to South Carolina and 27 years after the war, when he wrote his account, they were happily enjoying their lives and family together.

The Elmira Question

A great story. Romance. Drama. But I can’t help asking the questions: Was it the Fates that brought the couple together at Elmira? Or was it odds accumulating into coincidence that a man saved in Virginia unknowingly saved his saviour in New York? Or was it God that prompted a young woman in Elmira to choose one particular Rebel prisoner for salvation?

J. M. Waddill doesn’t suggest an answer, but the answer would necessarily apply to the entire Civil War.

So, what do you thing? Coincidence? Fate? God’s invisible hand? Other? Let me know.

In my next blog, I’ll write a bit more on the topic and include my take.

Sources:

¹ Vickers, George Morley. Under Both Flags: A Panorama of the Great Civil War. Veteran Publishing Company, 1896. Google Books. Web. 8 January 2015. books.goggle.com. Anecdote is found on page 176-182, <http://ow.ly/H0MUS>

² Gray, Michael P. The Business of Captivity: Elmira and Its Civil War Prison. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2001. Google Books. Web. 8 January 2015. books.google.com <http://ow.ly/H1qrk>

“Elmira Prison.” Wikipedia. N.p., n.d. Web. 9 Jan. 2015. .

Note: If you’re interested in reading more Elmira, especially primary sources, visit:

Scott, Brian. Elmira Prison Camp OnLine Library. Weblog site. Elmira Prison Camp OnLine Library. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 Jan. 2015.

The post An Amazing, Inspiring Elmira Prison Story and a Question appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.