David Pilling's Blog, page 68

July 13, 2016

The Hooded Man cometh (again)

After claiming I rarely write reviews, I now find myself writing two in a row. This one is for Robin Hood and the Knights of the Apocalypse, a brand-new audio episode of Robin of Sherwood. For those who don't know, RoS (to use a convenient acronym) was a British TV series back in the 80s that offered a very different take on the legend of Robin Hood. More realistic in some ways - the outlaws were a convincing bunch of roughnecks living inside a damp English forest, a world away from the sun-drenched Californian redwoods of the 1938 Errol Flynn flick - it was also the first screen version of the tale to introduce pagan elements. Unlike the devout Catholic outlaw of the medieval ballads, this Robin served Herne the Hunter, an ancient spirit of the forest, and took on the guise of The Hooded Man in the fight against Norman oppression.

For many Robin of Sherwood is *the* definitive screen version of the tale, and certain elements have influenced almost every version since: for instance, it was the first to introduce the idea of a deadly Saracen warrior among Robin's band of freedom fighters. This notion was picked up - or ripped off, to be unkind - and recycled in Kevin Costner's Prince of Thieves (1991) and the more recent BBC Robin Hood (2006-09). Alan Rickman's notoriously over-the-top turn as the evil Sheriff of Nottingham also owed much to Nickolas Grace's villainous Sheriff in RoS, though for my money Grace's performance was far more subtle and interesting.

So to Robin Hood and the KOTA. Before I go any further, I should acknowledge the huge degree of love and care and effort that went into this project. It was no mean feat on the part of Barnaby Eaton-Jones and his friends at Spiteful Puppet to gather all the surviving cast, raise the money needed to fund the recording (via crowdfunding), as well as hack through the legal jungle simply to persuade ITV (who own the rights to the series) to allow the project to go ahead. Also worth mentioning is that all the money raised from sales of the recording will go to charity.

Now for the difficult bit. I'm a fan of the original show - though nowhere near as devoted or knowledgeable as many fans - and my expectations for the actual quality of the new episode were modest. Granted, Spiteful Puppet were using a leftover script by the show's creator and original screenwriter, the late Richard Carpenter, but after thirty years could they really hope to recapture the magic? Early reviews were extremely positive, bordering on the ecstatic, so my hopes were raised a little.

After listening to KOTA twice, I have to say my reaction is mixed. It's not the car crash I was dreading, far from it, but nor does it come anywhere close to the heights of the first two seasons of RoS. Part of the problem is the awkwardness of fitting a script intended for a feature-length screen film into audio format. The action scenes in particular suffer, though the producers did their best by adding swishing arrows, clanging swords, galloping hoofs etc. None of these studio tricks, impressive as they are - and KOTA is very well produced - can suppress the unintentional comedy of actors describing the action as it happens: "my sword is at your neck," Nasir grimly informs a defeated opponent at one point. Unless he's fighting a blind man, his opponent would presumably know that already.

Such criticism is perhaps unfair, since the only remedy would be to cut out the action scenes altogether. Sadly there are other issues. The script itself is derivative of earlier TV episodes, and at times comes across like an edited highlights package: Robin is once again captured by insane cultists, as he was in The Time of the Wolf, and once again has to fight a manifested demon, as he did in The Swords of Wayland (though to be fair that was Robin of Loxley, rather than his successor Robert of Huntingdon). Some of the dialogue is very clunky by Carpenter's standards, and the banter between the Merries largely falls flat. Little John and Will Scarlet, played by Clive Mantle and Ray Winstone, are given some deeply unfunny jokes to work with, while the clumsy dialogue is not helped by a hefty slice of ham acting. Colin Baker is far too shrill as the villain Gerard de Ridefort, which makes his character come across as a dull, pompous buffoon. Fortunately Anthony Head rescues the situation with a nicely understated performance as the chief villain, Guichard de Montbalm, though even he occasionally breaks into some startling Dr Evil-style peals of maniacal laughter.

Elsewhere the cast suffers from one unavoidable omission. The late Robert Addie, so memorable as the Sheriff's blustering right-hand man Guy of Gisburne, was replaced by Freddie Fox. Fox is by no means bad as Guy, and has a certain sneering menace all of his own, but he sounds nothing at all like Addie. The difference jars, at least to my ears, and it might have been a better idea to omit Guy altogether and invent a new character for Fox. Nickolas Grace as the Sheriff initially sounds uncertain, as though he struggled to re-inhabit a character left behind thirty years ago (he isn't alone in this) but by the end of the episode he's back to his best, coldly informing the wounded Guy that he 'was never any good' and leaving him to bleed.

In case all this negativity sounds depressing or infuriating, I should point out some good bits. Jason Connery is very good as Robert of Huntingdon, and perhaps gives his best performance in the role. Connery's performance in the old series still divides opinion among fans, some of whom maintain he was too young and callow for the part and not a patch on his predecessor, Michael Praed. Now, three decades on, his voice has a deeper timbre and he carries it with more authority. At times he comes across like an exasperated staff officer, curtly snapping orders at the Merries, which makes him less charming but more realistic: Robert is supposed to be a young nobleman turned outlaw in charge of a bunch of unruly wolfsheads, not all of whom welcomed his leadership at first.

Robert's relationship with Marion is kept firmly in the background, perhaps wisely since the slightly unconvincing nature of it was one of the problems of the show. However this undercuts the big dramatic moment at the end of the third season when a heartbroken Marion, thinking Robert was dead, chose to go into a convent. Her decision to come out again and rejoin him in Sherwood is dealt with in just a couple of passing lines, which is a bit of a letdown - at least for those of who enjoy wallowing in melodrama (as I do).

A mention should also go to Mark Ryan as Nasir. The brooding Nasir was given hardly any lines in the original show, but here he is almost chatty and surprisingly engaging. His brief monologue with a bird in a tree, turning to rage when the birds are all frightened away by de Ridefort, is one of the best moments. Phil Rose as Friar Tuck gets a nice scene where he baptises infants in defiance of the Interdict, but otherwise has little to do except a few fat jokes.

Another nice feature is an enlarged role for Michael Craig as Robert's father, the Earl of Huntingdon. At one point the earl is called David, pretty much confirming that he is supposed to be the historical David of Huntingdon (1144-1219), brother to a King of Scotland. This in turn makes Robert an immensely powerful man if he wants to be, not only the heir to an earldom but with a decent claim to the Scottish throne. Disappointingly - at least for a history nerd like me - little is ever made of these connections, or the potentially fascinating narrative arc. As earl, with money and power and soldiers and a king for an ally, Robert would stand a fair better chance of defeating injustice and curbing the excesses of King John. Instead he chooses to wander back to Sherwood and spend his days mooning over Marion and listening to some laddish banter. Oh well.

Despite my many criticisms of KOTA, it did leave me wanting more. There is life in this old dog (or wolfshead) yet, and plenty more scope for further adventures. Further audio episodes, provided the demand exists for them, would actually be written for audio and thus remove the problems of retro-fitting a screenplay. I see no reason why a team of able writers, steeped in RoS lore, couldn't produce quality scripts that would do the story justice and bring it to an intelligent conclusion. Now we just need to find an eccentric millionaire or two to fund it...

Published on July 13, 2016 05:44

July 8, 2016

Henry IV

Book reviews generally aren't my forte, but I've just finished reading a new biography of Henry IV by Chris Given-Wilson, professor of Medieval History at the University of Saint Andrews. The book is excellent, if very detailed and extensive and perhaps not for a casual reader, so I thought I would try my hand at a review.

Henry IV is one of those kings that failed to capture the popular imagination. Sandwiched between his flamboyant cousin Richard II and famous son Henry V, he tends to get treated as a mediocre stopgap. His relatively short reign of 14 years was enlivened by the Glyn Dwr revolt and dynamic personalities such as Harry 'Hotspur' and the dashing Prince Hal, but Henry himself remains firmly in the background, a stolid, uninteresting figure of limited ability whose main achievement in life was to father a hero.

Chris Given-Wilson's exhaustive biography of Henry should go a long way to changing this perception. Academic but accessible, Given-Wilson gives a roughly chronological account of the reign and provides detailed analysis of major aspects: the king's household, the duchy of Lancaster, Henry's struggle for solvency, the war at sea, his wars in Wales and Scotland, the problem of heresy (etc). The book is particularly strong on Henry's youth and his military adventures in Lithuania, where he won a great reputation as a crusader. As a young man Henry was a star of European chivalry, a friend and comrade-in-arms to French and Italian princes, showered with praise by the chroniclers of all nations and lusted after by an Italian noblewoman, Lucia Galeazzo: Lucia declared that she 'would have waited all the days of her life' to marry Henry, even if it meant she would 'die but three days after the marriage.' Henry was flattered, but the starstruck Lucia had to make do with marrying the Earl of Kent instead.

Having deposed Richard II and upset the balance of power in England, within a very short time Henry found himself up to his neck in troubles. Wales exploded in revolt under the charismatic Owain Glyn Dwr, the Scots and the French declared war, the duchy of Guyenne was overrun, Ireland was in turmoil, and England itself threatened to dissolve into civil war. Henry's early blunders, such as the oppressive Penal Laws he threw at the Welsh and his execution of Archbishop Scrope, only served to inflame the situation. His efforts to reduce Wales by leading a series of hopeless chevauchées, all driven back by appalling weather, further damaged his reputation. Henry's foolish refusal to discuss terms with Glyn Dwr, when the rebel leader offered them in 1402-3, prolonged the revolt for another ten years and almost led to an independent Welsh state.

The great crisis of Henry's reign came in 1403 when his former ally Hotspur suddenly raised the banner of revolt against him. Had the rebels been joined at this crucial juncture by Glyn Dwr's army, the reign might well have ended in disaster and Henry himself consigned to the list of failed usurpers. In the event Hotspur rose too soon and Henry reacted with a speed his enemies clearly didn't think him capable of. The close-run Battle of Shrewsbury, where Hotspur was killed and Henry triumphed, marked the turning point. From then on, Henry's fortunes improved and he learned from his mistakes. The English strategy in Wales changed from one of chevauchée to economic blockade, while the French alliance with Glyn Dwr was carefully unpicked by skilled diplomacy. At sea the French were repeatedly humiliated by a fleet of merchant-privateers, tacitly encouraged by Henry, until the Privateer War (as it was known) ended with English ships in command of the Channel. When the Percies rose again, Henry again acted swiftly, racing north to smash the northern conspiracy and reduce the Percy castles with artillery: the first King of England to use cannon against rebels on English soil. By the end of his reign, an English army under Henry's son Clarence was marching virtually unopposed across French soil - the first successful invasion of France since the high days of Edward III - and the rival French factions were begging for Henry's friendship. Most importantly, from his point of view, the English overseas possessions of Calais and the duchy of Guyenne were secured for another generation.

Often criticised by his parliaments, at times embarrassed by the invective hurled at him, Henry was careful never to play the role of a wilful tyrant in the Richard II mould: he listened to criticism without suppressing it, engaged with his critics and several times handed over control of his finances. In an age of supremely personal kingship, when the king was still very much the god-figure at the heart of government, Henry took pains to rule with a degree of consent. At the same time he behaved with implacable savagery towards those he deemed traitors. The fate of William Serle, repeatedly hanged and then cut down while still alive in every major town from Pontefract to London until finally cut to pieces at Tyburn, is one hideous example. Serle's excruciating progress from Yorkshire to London followed the same route as the corpse of Richard II, and was meant as a calculated act of political theatre. Yet Henry was also noted for his generosity to paupers, several examples of which are recorded. The man who ordered 'traitors' to be slowly hacked to death in public was the same who granted a starving beggar two rabbits a day from one of his parks instead of one, demonstrating the almost schizophrenic nature of medieval kings: terrible to their foes, gentle to the faithful..

In his conclusion Given-Wilson suggests that Henry's real misfortune was to fall sick just at the moment when he had achieved a measure of security. Only forty-six when he died, Henry might have reasonably expected to live for at least another decade. With all his enemies laid low and his finances - a problem throughout the rein - finally on the mend, he could have turned his considerable natural ability to governing his kingdom instead of merely hanging onto it. Instead his fate was to die of a gruesome lingering sickness which left him horribly disfigured and unable to walk or ride. The security he had achieved after years of struggle was instead exploited to the full by his son, Henry V, known to any history buff as the victor of Agincourt.

I'll leave the last line to the author: 'Unlike his son, Henry IV is not remembered as a great king, but it is not impossible to imagine that, given different circumstances, he could have been.'

Henry IV is one of those kings that failed to capture the popular imagination. Sandwiched between his flamboyant cousin Richard II and famous son Henry V, he tends to get treated as a mediocre stopgap. His relatively short reign of 14 years was enlivened by the Glyn Dwr revolt and dynamic personalities such as Harry 'Hotspur' and the dashing Prince Hal, but Henry himself remains firmly in the background, a stolid, uninteresting figure of limited ability whose main achievement in life was to father a hero.

Chris Given-Wilson's exhaustive biography of Henry should go a long way to changing this perception. Academic but accessible, Given-Wilson gives a roughly chronological account of the reign and provides detailed analysis of major aspects: the king's household, the duchy of Lancaster, Henry's struggle for solvency, the war at sea, his wars in Wales and Scotland, the problem of heresy (etc). The book is particularly strong on Henry's youth and his military adventures in Lithuania, where he won a great reputation as a crusader. As a young man Henry was a star of European chivalry, a friend and comrade-in-arms to French and Italian princes, showered with praise by the chroniclers of all nations and lusted after by an Italian noblewoman, Lucia Galeazzo: Lucia declared that she 'would have waited all the days of her life' to marry Henry, even if it meant she would 'die but three days after the marriage.' Henry was flattered, but the starstruck Lucia had to make do with marrying the Earl of Kent instead.

Having deposed Richard II and upset the balance of power in England, within a very short time Henry found himself up to his neck in troubles. Wales exploded in revolt under the charismatic Owain Glyn Dwr, the Scots and the French declared war, the duchy of Guyenne was overrun, Ireland was in turmoil, and England itself threatened to dissolve into civil war. Henry's early blunders, such as the oppressive Penal Laws he threw at the Welsh and his execution of Archbishop Scrope, only served to inflame the situation. His efforts to reduce Wales by leading a series of hopeless chevauchées, all driven back by appalling weather, further damaged his reputation. Henry's foolish refusal to discuss terms with Glyn Dwr, when the rebel leader offered them in 1402-3, prolonged the revolt for another ten years and almost led to an independent Welsh state.

The great crisis of Henry's reign came in 1403 when his former ally Hotspur suddenly raised the banner of revolt against him. Had the rebels been joined at this crucial juncture by Glyn Dwr's army, the reign might well have ended in disaster and Henry himself consigned to the list of failed usurpers. In the event Hotspur rose too soon and Henry reacted with a speed his enemies clearly didn't think him capable of. The close-run Battle of Shrewsbury, where Hotspur was killed and Henry triumphed, marked the turning point. From then on, Henry's fortunes improved and he learned from his mistakes. The English strategy in Wales changed from one of chevauchée to economic blockade, while the French alliance with Glyn Dwr was carefully unpicked by skilled diplomacy. At sea the French were repeatedly humiliated by a fleet of merchant-privateers, tacitly encouraged by Henry, until the Privateer War (as it was known) ended with English ships in command of the Channel. When the Percies rose again, Henry again acted swiftly, racing north to smash the northern conspiracy and reduce the Percy castles with artillery: the first King of England to use cannon against rebels on English soil. By the end of his reign, an English army under Henry's son Clarence was marching virtually unopposed across French soil - the first successful invasion of France since the high days of Edward III - and the rival French factions were begging for Henry's friendship. Most importantly, from his point of view, the English overseas possessions of Calais and the duchy of Guyenne were secured for another generation.

Often criticised by his parliaments, at times embarrassed by the invective hurled at him, Henry was careful never to play the role of a wilful tyrant in the Richard II mould: he listened to criticism without suppressing it, engaged with his critics and several times handed over control of his finances. In an age of supremely personal kingship, when the king was still very much the god-figure at the heart of government, Henry took pains to rule with a degree of consent. At the same time he behaved with implacable savagery towards those he deemed traitors. The fate of William Serle, repeatedly hanged and then cut down while still alive in every major town from Pontefract to London until finally cut to pieces at Tyburn, is one hideous example. Serle's excruciating progress from Yorkshire to London followed the same route as the corpse of Richard II, and was meant as a calculated act of political theatre. Yet Henry was also noted for his generosity to paupers, several examples of which are recorded. The man who ordered 'traitors' to be slowly hacked to death in public was the same who granted a starving beggar two rabbits a day from one of his parks instead of one, demonstrating the almost schizophrenic nature of medieval kings: terrible to their foes, gentle to the faithful..

In his conclusion Given-Wilson suggests that Henry's real misfortune was to fall sick just at the moment when he had achieved a measure of security. Only forty-six when he died, Henry might have reasonably expected to live for at least another decade. With all his enemies laid low and his finances - a problem throughout the rein - finally on the mend, he could have turned his considerable natural ability to governing his kingdom instead of merely hanging onto it. Instead his fate was to die of a gruesome lingering sickness which left him horribly disfigured and unable to walk or ride. The security he had achieved after years of struggle was instead exploited to the full by his son, Henry V, known to any history buff as the victor of Agincourt.

I'll leave the last line to the author: 'Unlike his son, Henry IV is not remembered as a great king, but it is not impossible to imagine that, given different circumstances, he could have been.'

Published on July 08, 2016 06:52

June 23, 2016

New blog

I'm back from my travels in the Marches (in other words, Chester and North Wales) and would like to draw attention to a new joint blog, shared with my co-author Martin Bolton, which has now gone live. See the link below:

The World Apparent blog

The focus of the blog is fantasy fiction and relevant subjects, as opposed to the mainly historical themes on here. If it sparks your fantasy, please do take a look - the first post, written by myself, is a short article on Robert E. Howard, creator of Conan the Barbarian and Solomon Kane (among other characters). Comment on the post to enter a draw for a free copy of one of our fantasy novels, The Best Weapon or The Path of Sorrow!

The World Apparent blog

The focus of the blog is fantasy fiction and relevant subjects, as opposed to the mainly historical themes on here. If it sparks your fantasy, please do take a look - the first post, written by myself, is a short article on Robert E. Howard, creator of Conan the Barbarian and Solomon Kane (among other characters). Comment on the post to enter a draw for a free copy of one of our fantasy novels, The Best Weapon or The Path of Sorrow!

Published on June 23, 2016 02:46

June 11, 2016

John Page, soldier and poet and...?

Before I head away from the land of the internet for a week - on a research trip to Chester and its surroundings, which should be fun - I thought I would provide some context for John Page, the (somewhat reluctant) hero of my current trilogy, Soldier of Fortune.

Page is based on a real-life Englishman of the real name, of whom almost nothing is known. The only enduring mark he left on history was a poem, 'The Siege of Rouen', an eyewitness narrative account set to verse of Henry V's siege of Rouen in 1418-19. The poem is unique in English verse in that it provides a first-hand account of contemporary warfare, and has been summarised as 'a complex mix of patriotism and compassion, verse chronicle and historical romance.'

Only a single version of the poem survives, inside a version of the Middle English 'Brut' chronicle. Page's intent was to flatter the king and his nobles, principally the Duke of Clarence and the Duke of Exeter, whom he describes in glowing terms as men of 'great renown.' Apart from sucking up to royalty, Page's account is invaluable for its description of siege tactics and the brutality of 15th century warfare. He begins by describing the siege of Rouen as an epic event, greater than the sieges of Jerusalem or Troy:

'And no more solemn siege was set.Since Jerusalem or Troy were got...'

Page was exaggerating, but the siege and eventual capture of Rouen was perhaps Henry V's greatest victory, of more long-term significance than his more famous triumph at Agincourt in 1415. Rouen was the ducal capital of Normandy, Henry's ancestral homeland, and its capture gave the English a solid foothold in northern France. The king, who had cut his teeth fighting in Wales, was an expert in siege warfare: the city was surrounded on all sides by a network of ditches and trenches, while bands of Irish knife-men were sent out to scour the countryside for enemy troops, prevent supplies reaching the town and destroy French villages.

The poet doesn't shy away from the grim realities of the siege and the appalling conditions faced by the people trapped inside. As winter came on and food ran low he describes the citizens forced to feed on some less than choice delicacies: 'horses, dogs, casts, mice, rats and other things not belonging to human kind...'

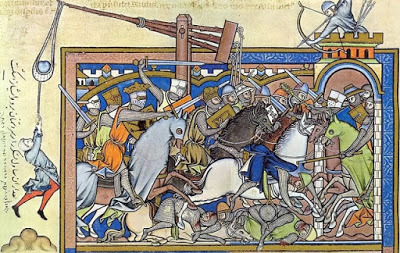

Siege of RouenFrench chroniclers accused Henry of refusing to allow the poorer citizens, ejected from the city as useless mouths, to pass through his siege lines. His hard-heartedness condemned the citizens to starve in the ditch below the walls, and there are horrifying accounts of babies being winched up to the ramparts in baskets to be baptised, then lowered again to die. Page admits that the city was starved into surrender - 'hunger breaks the stone walls' - but gives a different account of Henry's actions. According to him, Henry allowed his captains and private soldiers to take food to the citizens in the ditch if they wished, but refused any personal responsibility for their plight. "Who put them there?" he demanded of a party of French ambassadors when they begged him to allow the citizens through, "if the French wish to torment each other, it is none of my affair." The hard truth was that Henry had come to Normandy presenting himself as the scourge of the French nation, sent by God to chastise a corrupt people. He regarded the ejection of the citizens of Rouen as a deliberate ploy by the French to challenge his claim, and he could not afford to show mercy without being perceived as weak.

Siege of RouenFrench chroniclers accused Henry of refusing to allow the poorer citizens, ejected from the city as useless mouths, to pass through his siege lines. His hard-heartedness condemned the citizens to starve in the ditch below the walls, and there are horrifying accounts of babies being winched up to the ramparts in baskets to be baptised, then lowered again to die. Page admits that the city was starved into surrender - 'hunger breaks the stone walls' - but gives a different account of Henry's actions. According to him, Henry allowed his captains and private soldiers to take food to the citizens in the ditch if they wished, but refused any personal responsibility for their plight. "Who put them there?" he demanded of a party of French ambassadors when they begged him to allow the citizens through, "if the French wish to torment each other, it is none of my affair." The hard truth was that Henry had come to Normandy presenting himself as the scourge of the French nation, sent by God to chastise a corrupt people. He regarded the ejection of the citizens of Rouen as a deliberate ploy by the French to challenge his claim, and he could not afford to show mercy without being perceived as weak.

The poet himself is a shadowy figure. We know nothing of him save the little he chooses to tell us. His reason for being present at the siege - 'at that siege with the king I lay' - is unknown, and the poem reveals nothing of his status or background. One theory is that he can be identified with a John Page who was Prior of Barnwell at the time, though it is unclear why the Prior of Barnwell should have been present at a siege in Normandy. 'John Page' was a fairly common name and the muster rolls listed on the Medieval Soldier Database reveal nine archers of that name serving in Henry V's army between 1415-17: one served under the Duke of Gloucester in the Normandy expedition that culminated in the siege of Rouen. Hence it could be that the poet was one of these archers - a very unusual archer, literate and with a taste for poetry, who penned his work for the ages and then vanished back into the faceless throng, lost to history forever.

Page is based on a real-life Englishman of the real name, of whom almost nothing is known. The only enduring mark he left on history was a poem, 'The Siege of Rouen', an eyewitness narrative account set to verse of Henry V's siege of Rouen in 1418-19. The poem is unique in English verse in that it provides a first-hand account of contemporary warfare, and has been summarised as 'a complex mix of patriotism and compassion, verse chronicle and historical romance.'

Only a single version of the poem survives, inside a version of the Middle English 'Brut' chronicle. Page's intent was to flatter the king and his nobles, principally the Duke of Clarence and the Duke of Exeter, whom he describes in glowing terms as men of 'great renown.' Apart from sucking up to royalty, Page's account is invaluable for its description of siege tactics and the brutality of 15th century warfare. He begins by describing the siege of Rouen as an epic event, greater than the sieges of Jerusalem or Troy:

'And no more solemn siege was set.Since Jerusalem or Troy were got...'

Page was exaggerating, but the siege and eventual capture of Rouen was perhaps Henry V's greatest victory, of more long-term significance than his more famous triumph at Agincourt in 1415. Rouen was the ducal capital of Normandy, Henry's ancestral homeland, and its capture gave the English a solid foothold in northern France. The king, who had cut his teeth fighting in Wales, was an expert in siege warfare: the city was surrounded on all sides by a network of ditches and trenches, while bands of Irish knife-men were sent out to scour the countryside for enemy troops, prevent supplies reaching the town and destroy French villages.

The poet doesn't shy away from the grim realities of the siege and the appalling conditions faced by the people trapped inside. As winter came on and food ran low he describes the citizens forced to feed on some less than choice delicacies: 'horses, dogs, casts, mice, rats and other things not belonging to human kind...'

Siege of RouenFrench chroniclers accused Henry of refusing to allow the poorer citizens, ejected from the city as useless mouths, to pass through his siege lines. His hard-heartedness condemned the citizens to starve in the ditch below the walls, and there are horrifying accounts of babies being winched up to the ramparts in baskets to be baptised, then lowered again to die. Page admits that the city was starved into surrender - 'hunger breaks the stone walls' - but gives a different account of Henry's actions. According to him, Henry allowed his captains and private soldiers to take food to the citizens in the ditch if they wished, but refused any personal responsibility for their plight. "Who put them there?" he demanded of a party of French ambassadors when they begged him to allow the citizens through, "if the French wish to torment each other, it is none of my affair." The hard truth was that Henry had come to Normandy presenting himself as the scourge of the French nation, sent by God to chastise a corrupt people. He regarded the ejection of the citizens of Rouen as a deliberate ploy by the French to challenge his claim, and he could not afford to show mercy without being perceived as weak.

Siege of RouenFrench chroniclers accused Henry of refusing to allow the poorer citizens, ejected from the city as useless mouths, to pass through his siege lines. His hard-heartedness condemned the citizens to starve in the ditch below the walls, and there are horrifying accounts of babies being winched up to the ramparts in baskets to be baptised, then lowered again to die. Page admits that the city was starved into surrender - 'hunger breaks the stone walls' - but gives a different account of Henry's actions. According to him, Henry allowed his captains and private soldiers to take food to the citizens in the ditch if they wished, but refused any personal responsibility for their plight. "Who put them there?" he demanded of a party of French ambassadors when they begged him to allow the citizens through, "if the French wish to torment each other, it is none of my affair." The hard truth was that Henry had come to Normandy presenting himself as the scourge of the French nation, sent by God to chastise a corrupt people. He regarded the ejection of the citizens of Rouen as a deliberate ploy by the French to challenge his claim, and he could not afford to show mercy without being perceived as weak. The poet himself is a shadowy figure. We know nothing of him save the little he chooses to tell us. His reason for being present at the siege - 'at that siege with the king I lay' - is unknown, and the poem reveals nothing of his status or background. One theory is that he can be identified with a John Page who was Prior of Barnwell at the time, though it is unclear why the Prior of Barnwell should have been present at a siege in Normandy. 'John Page' was a fairly common name and the muster rolls listed on the Medieval Soldier Database reveal nine archers of that name serving in Henry V's army between 1415-17: one served under the Duke of Gloucester in the Normandy expedition that culminated in the siege of Rouen. Hence it could be that the poet was one of these archers - a very unusual archer, literate and with a taste for poetry, who penned his work for the ages and then vanished back into the faceless throng, lost to history forever.

Published on June 11, 2016 03:54

May 25, 2016

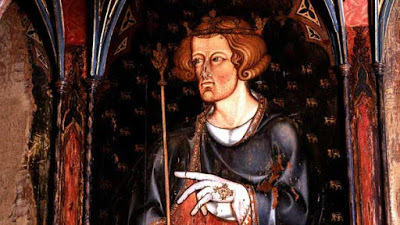

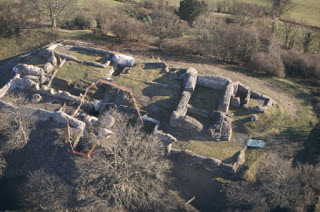

Edwardian armies

This is another in a series of blog posts on the military aspects of Edward I's reign. Some may call it an obsession, but it could be worse - I could be a Ricardian (that's a joke, in case any Ricardians out there are reading this.)

Warning: the rest of this post is a bit of a nerdfest, so any readers with no particular interest in military terms and military history might want to look away now...

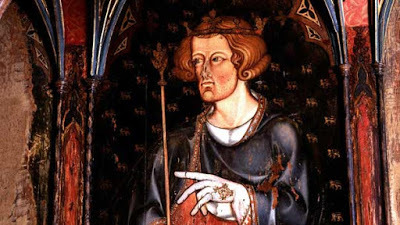

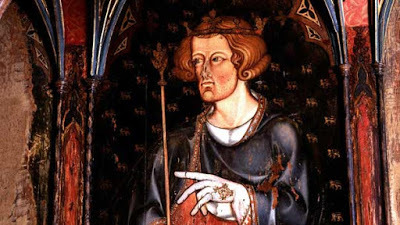

Yep. Him again.Edward seldom gets any credit for the way he restructured the old-fashioned English feudal host. He introduced the concept of paid military service in place of feudal dues and privileges, as well as a new command structure and innovative tactics. His reforms were by no means thorough, and many of them fell away during the reign of his son, Edward II, to be picked up again and improved to perfection by Edward III. Nevertheless, it was old man Longshanks who got the ball rolling.

Yep. Him again.Edward seldom gets any credit for the way he restructured the old-fashioned English feudal host. He introduced the concept of paid military service in place of feudal dues and privileges, as well as a new command structure and innovative tactics. His reforms were by no means thorough, and many of them fell away during the reign of his son, Edward II, to be picked up again and improved to perfection by Edward III. Nevertheless, it was old man Longshanks who got the ball rolling.

Prior to Edward I, the English feudal army was reasonably large, but cumbersome and lacking in experience. The majority of Englishmen in the reign of Henry III were raw fighters, and made for poor soldiers, with the exception of those living on the Welsh March and the poachers and huntsmen of Sherwood, who enjoyed some reputation for archery. Otherwise native infantry were quite useless, and largely there to make up the numbers. Desertion rates were high, training minimal, and wages pathetic. The real military elite was still composed of the mounted knights and barons and their retinues. Knights never dismounted to fight - beneath their noble dignity - and companies of horse and foot never brigaded together.

Battles such as Lewes and Evesham were won by charges of heavy horse, while the hapless infantry were ridden down and slaughtered. At Lewes Simon de Montfort drew his knights up into three bodies with a reserve. They rode forward in a single level charge, 'boot to boot', the riders heavy in their mail coats and leggings, wielding couched lances that packed a mighty punch, but were massive and difficult to wield. Rapid movements and elaborate manoeuvres were impossible. These simple, inflexible tactics were exactly the same as used by Simon de Montfort's father at the Battle of Muret in 1213, and worked well enough so long as feudal hosts fought each other. In North Wales, where the natives avoided pitched battles and led the lumbering knights a merry dance in the mountains and forests, they were ineffective. Time after time, one English feudal host after another was 'beaten bootless back' - as Shakespeare put it - from Wales, defeated by Welsh guerilla tactics and Welsh weather.

Edward, who had ample experience in his youth of the difficulties of fighting in Wales, saw the need for change. I've described in a previous post his efforts to create a bow-armed infantry, but his reforms went further than that. His first task was organisation and the systematic use of paid contracts in place of feudal dues, which allowed him to reorganise the army along structured, professional lines. For instance, a baron or 'banneret' might be contracted to raise a company of a hundred or more lances. The company was itself divided into troops, with each smaller troop led by an officer on a sub-contract. This system allowed for subordination of command, which meant that companies could act independently under their own officers instead of relying entirely on the commander-in-chief.

Companies or squadrons of cavalry could join together to form a single 'brigade' under the overall command of the king, or be split apart again under one of his nobles. In 1277 the Earls of Warwick and Lincoln each had command of a company of 125 lances, while Pain de Chaworth had 75 lances. These men, including their leaders, were all contracted to serve for a renewable period of forty days. Troops led by earls, barons, knights and ordinary troopers could be subdivided into smaller units, each with an officer, depending on necessity. Most captains were men of some status - this was still the 13th century, after all - but performance was prized above noble blood. Even the Earl of Gloucester, one of the greatest nobles in the land, was stripped of his command after leading his troops to defeat at Llandeilo in 1282.

Until his conquest of Wales, the best footmen Edward could muster were the famed mercenary crossbowmen from his duchy of Gascony. These men, described as 'the Swiss of the 13th century', were expensive and summoned in relatively small numbers. 'They came pompously', according to one chronicler, and fought with an arrogant swagger worthy of D'Artagnan, perhaps the most famous Gascon of all. Langtoft described their performance in Wales:

A medieval D'Artagnan...

A medieval D'Artagnan...

'They (the Gascons) remain with the king, receive his gifts.

In moors and mountains they clamber like lions,

They go with the English, burn the houses,

Throw down the castles, slay the wretches,

They have passed the Marches, and entered into Snowdon..."

The king was not content to rely entirely on Welsh mercenaries and the 'lions' of Gascony for his infantry. He took steps to at least improve the organisation of English footsoldiers, as he had done with the cavalry. From 1277 onwards he appointed special officers in place of regional sheriffs to oversee the raising of footmen from the English shires, and these officers were tasked with picking the best and strongest men and forming them into regular companies. A company of English foot consisted of a hundred men, led by a mounted constable or centenar. Each company was divided into units of nineteen, led by under-officers or vintenars. Thus a proper system of pay and command was introduced, though desertion rates remained high and the quality of the average English footsoldier took decades to improve: for his war in France in 1294, Edward was compelled to recruit criminals and outlaws into the infantry, since none better could be found elsewhere.

Edward's introduction of new tactics and organisation, the combination of horse and foot and introduction of the Welsh longbow as a common weapon in English armies, all paid off. At Orewin Bridge, Maes Moydog and Falkirk his enemies were destroyed by units of cavalry, archers and crossbowmen working in concert. His troops had also learned guerilla tactics from the Welsh: after the victory of Maes Moydog, units of English and Gascons in camouflage gear (white cloaks so they merged into the snow) pursued the Welsh into their own mountains.

The king had learned from bitter experience, and there were plenty of bitter experiences to come before the glory days of Edward III. Falkirk was almost lost by a foolish charge of mounted knights, straight onto the Scottish spears, and the situation only restored by the arrival of Edward and his Gascons. The arrogance of the English baronage, their ingrained belief that they could still sweep all before them with a single mounted charge, was something the king could do little to eradicate. The result was total disaster at Bannockburn in 1314, where all the lessons of Edward I's reign were forgotten and the chivalry of England smashed to pieces on Bruce's schiltrons. Even thick-headed aristocrats could hardly ignore such a lesson, and the third Edward was savvy enough to remember the innovations of his grandfather, as well as introducing a few of his own.

Warning: the rest of this post is a bit of a nerdfest, so any readers with no particular interest in military terms and military history might want to look away now...

Yep. Him again.Edward seldom gets any credit for the way he restructured the old-fashioned English feudal host. He introduced the concept of paid military service in place of feudal dues and privileges, as well as a new command structure and innovative tactics. His reforms were by no means thorough, and many of them fell away during the reign of his son, Edward II, to be picked up again and improved to perfection by Edward III. Nevertheless, it was old man Longshanks who got the ball rolling.

Yep. Him again.Edward seldom gets any credit for the way he restructured the old-fashioned English feudal host. He introduced the concept of paid military service in place of feudal dues and privileges, as well as a new command structure and innovative tactics. His reforms were by no means thorough, and many of them fell away during the reign of his son, Edward II, to be picked up again and improved to perfection by Edward III. Nevertheless, it was old man Longshanks who got the ball rolling.Prior to Edward I, the English feudal army was reasonably large, but cumbersome and lacking in experience. The majority of Englishmen in the reign of Henry III were raw fighters, and made for poor soldiers, with the exception of those living on the Welsh March and the poachers and huntsmen of Sherwood, who enjoyed some reputation for archery. Otherwise native infantry were quite useless, and largely there to make up the numbers. Desertion rates were high, training minimal, and wages pathetic. The real military elite was still composed of the mounted knights and barons and their retinues. Knights never dismounted to fight - beneath their noble dignity - and companies of horse and foot never brigaded together.

Battles such as Lewes and Evesham were won by charges of heavy horse, while the hapless infantry were ridden down and slaughtered. At Lewes Simon de Montfort drew his knights up into three bodies with a reserve. They rode forward in a single level charge, 'boot to boot', the riders heavy in their mail coats and leggings, wielding couched lances that packed a mighty punch, but were massive and difficult to wield. Rapid movements and elaborate manoeuvres were impossible. These simple, inflexible tactics were exactly the same as used by Simon de Montfort's father at the Battle of Muret in 1213, and worked well enough so long as feudal hosts fought each other. In North Wales, where the natives avoided pitched battles and led the lumbering knights a merry dance in the mountains and forests, they were ineffective. Time after time, one English feudal host after another was 'beaten bootless back' - as Shakespeare put it - from Wales, defeated by Welsh guerilla tactics and Welsh weather.

Edward, who had ample experience in his youth of the difficulties of fighting in Wales, saw the need for change. I've described in a previous post his efforts to create a bow-armed infantry, but his reforms went further than that. His first task was organisation and the systematic use of paid contracts in place of feudal dues, which allowed him to reorganise the army along structured, professional lines. For instance, a baron or 'banneret' might be contracted to raise a company of a hundred or more lances. The company was itself divided into troops, with each smaller troop led by an officer on a sub-contract. This system allowed for subordination of command, which meant that companies could act independently under their own officers instead of relying entirely on the commander-in-chief.

Companies or squadrons of cavalry could join together to form a single 'brigade' under the overall command of the king, or be split apart again under one of his nobles. In 1277 the Earls of Warwick and Lincoln each had command of a company of 125 lances, while Pain de Chaworth had 75 lances. These men, including their leaders, were all contracted to serve for a renewable period of forty days. Troops led by earls, barons, knights and ordinary troopers could be subdivided into smaller units, each with an officer, depending on necessity. Most captains were men of some status - this was still the 13th century, after all - but performance was prized above noble blood. Even the Earl of Gloucester, one of the greatest nobles in the land, was stripped of his command after leading his troops to defeat at Llandeilo in 1282.

Until his conquest of Wales, the best footmen Edward could muster were the famed mercenary crossbowmen from his duchy of Gascony. These men, described as 'the Swiss of the 13th century', were expensive and summoned in relatively small numbers. 'They came pompously', according to one chronicler, and fought with an arrogant swagger worthy of D'Artagnan, perhaps the most famous Gascon of all. Langtoft described their performance in Wales:

A medieval D'Artagnan...

A medieval D'Artagnan...'They (the Gascons) remain with the king, receive his gifts.

In moors and mountains they clamber like lions,

They go with the English, burn the houses,

Throw down the castles, slay the wretches,

They have passed the Marches, and entered into Snowdon..."

The king was not content to rely entirely on Welsh mercenaries and the 'lions' of Gascony for his infantry. He took steps to at least improve the organisation of English footsoldiers, as he had done with the cavalry. From 1277 onwards he appointed special officers in place of regional sheriffs to oversee the raising of footmen from the English shires, and these officers were tasked with picking the best and strongest men and forming them into regular companies. A company of English foot consisted of a hundred men, led by a mounted constable or centenar. Each company was divided into units of nineteen, led by under-officers or vintenars. Thus a proper system of pay and command was introduced, though desertion rates remained high and the quality of the average English footsoldier took decades to improve: for his war in France in 1294, Edward was compelled to recruit criminals and outlaws into the infantry, since none better could be found elsewhere.

Edward's introduction of new tactics and organisation, the combination of horse and foot and introduction of the Welsh longbow as a common weapon in English armies, all paid off. At Orewin Bridge, Maes Moydog and Falkirk his enemies were destroyed by units of cavalry, archers and crossbowmen working in concert. His troops had also learned guerilla tactics from the Welsh: after the victory of Maes Moydog, units of English and Gascons in camouflage gear (white cloaks so they merged into the snow) pursued the Welsh into their own mountains.

The king had learned from bitter experience, and there were plenty of bitter experiences to come before the glory days of Edward III. Falkirk was almost lost by a foolish charge of mounted knights, straight onto the Scottish spears, and the situation only restored by the arrival of Edward and his Gascons. The arrogance of the English baronage, their ingrained belief that they could still sweep all before them with a single mounted charge, was something the king could do little to eradicate. The result was total disaster at Bannockburn in 1314, where all the lessons of Edward I's reign were forgotten and the chivalry of England smashed to pieces on Bruce's schiltrons. Even thick-headed aristocrats could hardly ignore such a lesson, and the third Edward was savvy enough to remember the innovations of his grandfather, as well as introducing a few of his own.

Published on May 25, 2016 04:59

May 17, 2016

Archers!

Anyone who reads this blog will know my interest in King Edward I and his military campaigns. Lately I've been reading about his early battles against the Welsh and the baronial rebels in England. These weren't always successful, and quite often ended in humiliating defeat for the young prince: in 1257 an army of mercenaries sent to pacify West Wales on his behalf was exterminated at Coed Llathen, while Edward himself was famously defeated and captured by Simon de Montfort at Lewes. Edward's lands in the March were ravaged by his bitter rival, Robert de Ferrers, the 'wild and flighty' Earl of Derby, who also (briefly) seized many of the prince's castles.

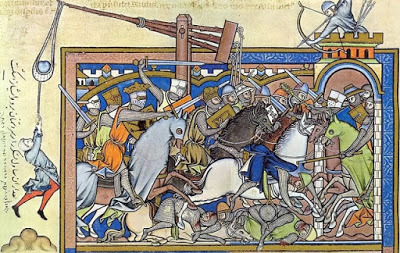

Battle scene from a 1200s MSThe watershed moment for Edward was the Battle of Evesham, where he turned the tables on his enemies and massacred de Montfort and his army. Here Edward gave the world a taste of the cold, machine-like efficiency that would define his later military career. De Montfort was hunted down on the field by a specially chosen death-squad led by the ruthless Marcher lord, Roger de Mortimer, while no quarter was given to the rebel knights and barons. Thirty noblemen were slain at Evesham, a small number compared to the thousands of common men slaughtered, but still the greatest number of nobles killed in a single battle in England since Hastings. Amid the reeking carnage and piles of dismembered corpses, Edward proved he had come of age.

Battle scene from a 1200s MSThe watershed moment for Edward was the Battle of Evesham, where he turned the tables on his enemies and massacred de Montfort and his army. Here Edward gave the world a taste of the cold, machine-like efficiency that would define his later military career. De Montfort was hunted down on the field by a specially chosen death-squad led by the ruthless Marcher lord, Roger de Mortimer, while no quarter was given to the rebel knights and barons. Thirty noblemen were slain at Evesham, a small number compared to the thousands of common men slaughtered, but still the greatest number of nobles killed in a single battle in England since Hastings. Amid the reeking carnage and piles of dismembered corpses, Edward proved he had come of age.

After Evesham, there was still plenty of fighting to do before England was settled. In the two years of hard campaigning that followed, Edward showed he had learned from his tough experiences in Wales and the March. In particular he had learned the value of the Welsh bow and the warlike qualities of Welsh soldiers, especially the archers of Gwent and Glamorgan and the spearmen of Gwynedd and Merioneth. In the spring and summer of 1266 Edward and his lieutenant, Roger Leyburn, were engaging in clearing out bands of rebels in the deep forests of the Sussex Weald and retaking the Cinque Ports, which controlled access to the Channel. This required hard fighting in thickly wooded areas, and the royal account rolls show that Edward and Leyburn hired over 500 Welsh archers to destroy the rebels hiding in the Weald. Since the Welsh were renowned as superb guerillas, skilled at ambushes and fighting in difficult terrain, they were ideal for the task.

Welsh archer, from a 14th century MSThese men were paid 3 pence a day, an unusually high wage: in Edward's later campaigns English archers were paid 2 pence a day, while his Welsh mercenaries only got 1. The Weald archers were provided with tunics priced at 3 shillings each, the cloth costing in all £30, while their total wages came to £143. This was a fairly considerable outlay, and it could be that the Welsh archers employed in this campaign were regarded as elite troops. After the rebels were defeated and the Cinque Ports reduced, many of the archers were left to guard Essex as a kind of police force. What the locals made of hundreds of Welshmen garrisoning their towns and villages is anyone's guess.

Welsh archer, from a 14th century MSThese men were paid 3 pence a day, an unusually high wage: in Edward's later campaigns English archers were paid 2 pence a day, while his Welsh mercenaries only got 1. The Weald archers were provided with tunics priced at 3 shillings each, the cloth costing in all £30, while their total wages came to £143. This was a fairly considerable outlay, and it could be that the Welsh archers employed in this campaign were regarded as elite troops. After the rebels were defeated and the Cinque Ports reduced, many of the archers were left to guard Essex as a kind of police force. What the locals made of hundreds of Welshmen garrisoning their towns and villages is anyone's guess.

The 12th century writer, Gerald of Wales, left a vivid description of Welsh soldiers:

"They are lightly armed so that their agility might not be impeded; they are clad in short garments of chain mail, have a handful of arrows, long lances, helmets and shields, but rarely appear with leg armour...those of the foot soldiers who have not bare feet, wear shoes made of raw hide, sewn up in a barbarous fashion. The people of Gwent are more accustomed to war, more famous for valour, and more expert in archery than those in any other part of Wales...."

Gerald goes on to describe the lethal efficacy of the Welsh bow, made of wild elm 'rude and uncouth, but strong', and tells of how arrows shot during an assault on Abergavenny Castle penetrated 'an iron gate which was four fingers thick...in memory of which the arrows are still preserved sticking in the gate.' Whether arrows shot from any kind of bow, even Welsh longbows, were capable of penetrating iron may be open to doubt, but Gerald's writings clearly show the Welsh bow was regarded as a fearsome weapon.

Edward wasn't the first King of England to realise the importance of archers - bowmen are mentioned in the assize of arms of Henry III's reign - but he did make a serious effort to create an organised, disciplined force of bow-armed infantry. A specially raised body of crossbowmen and archers was hired to root out rebels in Sherwood Forest in 1266, and archers from Notts and Derbyshire were often recruited to serve in his Welsh wars. In the 'little war of Chálons', fought in 1273 during Edward's return from Crusade, the French knights were dragged from their horses and butchered on the ground by Welsh bowmen and slingers in the king's retinue.

Edward wasn't the first King of England to realise the importance of archers - bowmen are mentioned in the assize of arms of Henry III's reign - but he did make a serious effort to create an organised, disciplined force of bow-armed infantry. A specially raised body of crossbowmen and archers was hired to root out rebels in Sherwood Forest in 1266, and archers from Notts and Derbyshire were often recruited to serve in his Welsh wars. In the 'little war of Chálons', fought in 1273 during Edward's return from Crusade, the French knights were dragged from their horses and butchered on the ground by Welsh bowmen and slingers in the king's retinue.

During the first Welsh war of 1277, two small, purely bow-armed corps of infantry were raised. One was drawn from Gwent and Crickhowell, the other (numbering a hundred men) from Macclesfield in Cheshire, close to the Welsh border. The Macclesfield corps served Edward as a personal guard, and the tradition of kings being guarded by a 'Macclesfield Hundred' was continued by Edward's descendants: Richard II was accompanied on his travels by a hundred Macclesfield and Welsh archers, kitted out in green and white livery (see right).

Edward's conquest of the Welsh heartlands gave him access to some of the best fighting men in Europe, and he wasn't the man to ignore such a resource. Many thousands of Welsh archers and spearmen were employed in his later wars in Gascony and Scotland (and Wales). The numbers of Welsh employed in English armies continued to rise during the reigns of Edward's immediate successors, reaching a high point in the Crécy campaign of 1346...but more of that in future posts.

Battle scene from a 1200s MSThe watershed moment for Edward was the Battle of Evesham, where he turned the tables on his enemies and massacred de Montfort and his army. Here Edward gave the world a taste of the cold, machine-like efficiency that would define his later military career. De Montfort was hunted down on the field by a specially chosen death-squad led by the ruthless Marcher lord, Roger de Mortimer, while no quarter was given to the rebel knights and barons. Thirty noblemen were slain at Evesham, a small number compared to the thousands of common men slaughtered, but still the greatest number of nobles killed in a single battle in England since Hastings. Amid the reeking carnage and piles of dismembered corpses, Edward proved he had come of age.

Battle scene from a 1200s MSThe watershed moment for Edward was the Battle of Evesham, where he turned the tables on his enemies and massacred de Montfort and his army. Here Edward gave the world a taste of the cold, machine-like efficiency that would define his later military career. De Montfort was hunted down on the field by a specially chosen death-squad led by the ruthless Marcher lord, Roger de Mortimer, while no quarter was given to the rebel knights and barons. Thirty noblemen were slain at Evesham, a small number compared to the thousands of common men slaughtered, but still the greatest number of nobles killed in a single battle in England since Hastings. Amid the reeking carnage and piles of dismembered corpses, Edward proved he had come of age. After Evesham, there was still plenty of fighting to do before England was settled. In the two years of hard campaigning that followed, Edward showed he had learned from his tough experiences in Wales and the March. In particular he had learned the value of the Welsh bow and the warlike qualities of Welsh soldiers, especially the archers of Gwent and Glamorgan and the spearmen of Gwynedd and Merioneth. In the spring and summer of 1266 Edward and his lieutenant, Roger Leyburn, were engaging in clearing out bands of rebels in the deep forests of the Sussex Weald and retaking the Cinque Ports, which controlled access to the Channel. This required hard fighting in thickly wooded areas, and the royal account rolls show that Edward and Leyburn hired over 500 Welsh archers to destroy the rebels hiding in the Weald. Since the Welsh were renowned as superb guerillas, skilled at ambushes and fighting in difficult terrain, they were ideal for the task.

Welsh archer, from a 14th century MSThese men were paid 3 pence a day, an unusually high wage: in Edward's later campaigns English archers were paid 2 pence a day, while his Welsh mercenaries only got 1. The Weald archers were provided with tunics priced at 3 shillings each, the cloth costing in all £30, while their total wages came to £143. This was a fairly considerable outlay, and it could be that the Welsh archers employed in this campaign were regarded as elite troops. After the rebels were defeated and the Cinque Ports reduced, many of the archers were left to guard Essex as a kind of police force. What the locals made of hundreds of Welshmen garrisoning their towns and villages is anyone's guess.

Welsh archer, from a 14th century MSThese men were paid 3 pence a day, an unusually high wage: in Edward's later campaigns English archers were paid 2 pence a day, while his Welsh mercenaries only got 1. The Weald archers were provided with tunics priced at 3 shillings each, the cloth costing in all £30, while their total wages came to £143. This was a fairly considerable outlay, and it could be that the Welsh archers employed in this campaign were regarded as elite troops. After the rebels were defeated and the Cinque Ports reduced, many of the archers were left to guard Essex as a kind of police force. What the locals made of hundreds of Welshmen garrisoning their towns and villages is anyone's guess. The 12th century writer, Gerald of Wales, left a vivid description of Welsh soldiers:

"They are lightly armed so that their agility might not be impeded; they are clad in short garments of chain mail, have a handful of arrows, long lances, helmets and shields, but rarely appear with leg armour...those of the foot soldiers who have not bare feet, wear shoes made of raw hide, sewn up in a barbarous fashion. The people of Gwent are more accustomed to war, more famous for valour, and more expert in archery than those in any other part of Wales...."

Gerald goes on to describe the lethal efficacy of the Welsh bow, made of wild elm 'rude and uncouth, but strong', and tells of how arrows shot during an assault on Abergavenny Castle penetrated 'an iron gate which was four fingers thick...in memory of which the arrows are still preserved sticking in the gate.' Whether arrows shot from any kind of bow, even Welsh longbows, were capable of penetrating iron may be open to doubt, but Gerald's writings clearly show the Welsh bow was regarded as a fearsome weapon.

Edward wasn't the first King of England to realise the importance of archers - bowmen are mentioned in the assize of arms of Henry III's reign - but he did make a serious effort to create an organised, disciplined force of bow-armed infantry. A specially raised body of crossbowmen and archers was hired to root out rebels in Sherwood Forest in 1266, and archers from Notts and Derbyshire were often recruited to serve in his Welsh wars. In the 'little war of Chálons', fought in 1273 during Edward's return from Crusade, the French knights were dragged from their horses and butchered on the ground by Welsh bowmen and slingers in the king's retinue.

Edward wasn't the first King of England to realise the importance of archers - bowmen are mentioned in the assize of arms of Henry III's reign - but he did make a serious effort to create an organised, disciplined force of bow-armed infantry. A specially raised body of crossbowmen and archers was hired to root out rebels in Sherwood Forest in 1266, and archers from Notts and Derbyshire were often recruited to serve in his Welsh wars. In the 'little war of Chálons', fought in 1273 during Edward's return from Crusade, the French knights were dragged from their horses and butchered on the ground by Welsh bowmen and slingers in the king's retinue. During the first Welsh war of 1277, two small, purely bow-armed corps of infantry were raised. One was drawn from Gwent and Crickhowell, the other (numbering a hundred men) from Macclesfield in Cheshire, close to the Welsh border. The Macclesfield corps served Edward as a personal guard, and the tradition of kings being guarded by a 'Macclesfield Hundred' was continued by Edward's descendants: Richard II was accompanied on his travels by a hundred Macclesfield and Welsh archers, kitted out in green and white livery (see right).

Edward's conquest of the Welsh heartlands gave him access to some of the best fighting men in Europe, and he wasn't the man to ignore such a resource. Many thousands of Welsh archers and spearmen were employed in his later wars in Gascony and Scotland (and Wales). The numbers of Welsh employed in English armies continued to rise during the reigns of Edward's immediate successors, reaching a high point in the Crécy campaign of 1346...but more of that in future posts.

Published on May 17, 2016 03:11

May 10, 2016

Soldier of Fortune (II): The Heretic

Drums...trumpets...pipes...fanfare...etc! As promised in my last post, Soldier of Fortune (II): The Heretic is now available on Kindle.

Kindle version on Amazon

“Ye who are God’s warriors and of His law...”

“Ye who are God’s warriors and of His law...”

Constantinople, 1453 AD. Sir John Page, English knight and mercenary captain, has been taken prisoner by the Ottoman Turks. To avoid execution, Page is forced to entertain the Sultan with stories of his adventures as a soldier in France, Bohemia and Italy.

In this, the second tale, Page describes his time among the fanatical Hussites in Bohemia. Condemned by the Pope as heretics, the Hussites dared to defy the might of the Catholic church and the Christian princes of Europe. In response the Pope ordered their destruction, down to the last child, and the brutal subjugation of their country.

Page joins the Hussites just as another crusade is launched against Bohemia. Led by the merciless King Sigismund, known as the Dragon of Prophecy, the crusaders will drown the land in blood rather than let heresy prevail. Bohemia’s only hope lies in Jan Zizka, a blind soldier of genius, and his army of peasant soldiers.

Caught up in a savage war of religion, Page struggles to earn the trust of his new comrades, who regard the Englishman as a potential spy. On bloody battlefields fought in nightmarish conditions, with his life and immortal soul at stake, Page is faced with a stark choice: win, or perish...

The paperback version will follow shortly - watch this space, as they say...

Kindle version on Amazon

“Ye who are God’s warriors and of His law...”

“Ye who are God’s warriors and of His law...”

Constantinople, 1453 AD. Sir John Page, English knight and mercenary captain, has been taken prisoner by the Ottoman Turks. To avoid execution, Page is forced to entertain the Sultan with stories of his adventures as a soldier in France, Bohemia and Italy.

In this, the second tale, Page describes his time among the fanatical Hussites in Bohemia. Condemned by the Pope as heretics, the Hussites dared to defy the might of the Catholic church and the Christian princes of Europe. In response the Pope ordered their destruction, down to the last child, and the brutal subjugation of their country.

Page joins the Hussites just as another crusade is launched against Bohemia. Led by the merciless King Sigismund, known as the Dragon of Prophecy, the crusaders will drown the land in blood rather than let heresy prevail. Bohemia’s only hope lies in Jan Zizka, a blind soldier of genius, and his army of peasant soldiers.

Caught up in a savage war of religion, Page struggles to earn the trust of his new comrades, who regard the Englishman as a potential spy. On bloody battlefields fought in nightmarish conditions, with his life and immortal soul at stake, Page is faced with a stark choice: win, or perish...

The paperback version will follow shortly - watch this space, as they say...

Published on May 10, 2016 01:58

April 25, 2016

The Soldier of Fortune cometh (again)

I interrupt my recent series of posts on Edward I and his wars in Wales to bring you news of my latest book. Titled Soldier of Fortune (II): The Heretic, this is the second of a planned trilogy following the adventures of Sir John Page, a semi-fictional English mercenary or 'soldier of fortune' in the early to mid-15th century.

Fall of ConstantinopleCaptured at the final siege of Constantinople in 1453, Page is literally forced to sing for his supper (or rather, his life) by the victorious Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed the Conqueror: to save his neck from the executioner's blade, Page must tell a series of Arabian Nights-style stories for the sultan's entertainment. As an old soldier with a long military career behind him, Page chooses to tell stories from his own life - possibly a little exaggerated, but only he knows that.

Fall of ConstantinopleCaptured at the final siege of Constantinople in 1453, Page is literally forced to sing for his supper (or rather, his life) by the victorious Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed the Conqueror: to save his neck from the executioner's blade, Page must tell a series of Arabian Nights-style stories for the sultan's entertainment. As an old soldier with a long military career behind him, Page chooses to tell stories from his own life - possibly a little exaggerated, but only he knows that.

Having already recited his first tale, based on his early career as a soldier in Normandy in the army of King Henry V, Page now recounts his time among the Hussites in war-torn Bohemia (part of the modern-day Czech Republic). The Hussites were followers of the martyred Bohemian preacher, Jan Hus, who was burned at the stake as a heretic in Constance in 1415. Hus was a radical who believed in cleansing the Catholic church of sin and corruption, and unsurprisingly hated by the Pope. After being thrown out of Prague University he wandered the country, preaching his ideals to the poor. He gained immense popular support, and when the news of his death reached Bohemia the people flew to arms to avenge him.

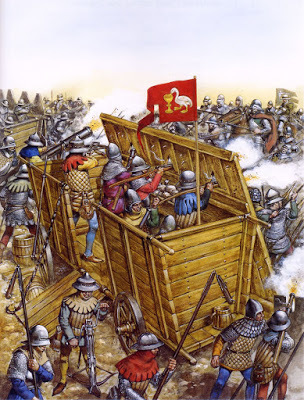

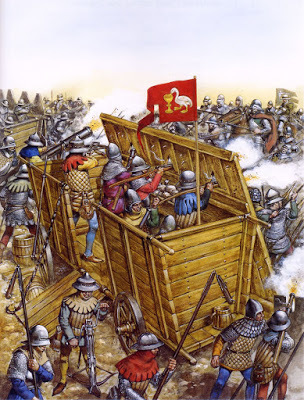

The Hussite armies were essentially made up of peasants, supported by a handful of nobles. Outnumbered and (supposedly) outclassed by the vast armies commanded by the Pope and his allies in Germany and Hungary, they should have been wiped out in a matter of weeks. Instead, thanks to innovative battle tactics and superb use of artillery, they won a series of unlikely victories against the odds. Thus the cream of the elite warrior nobility of Christendom was humiliated, time and again, by a few thousand commoners and some farm carts converted into gun-toting 'war wagons'.

The Hussite Wars, as they were called, raged for seventeen years. Page's story covers the years 1421-24, when the wars were at their height. For his sins, Page fights in the major battles and sieges, and witnesses some of the worst atrocities committed in a land riven by bitter civil conflicts, external invasions and extreme religious zealotry. During the course of the tale Page meets Jan Zizka, the famous Hussite general, meets a new love and loses old friends.

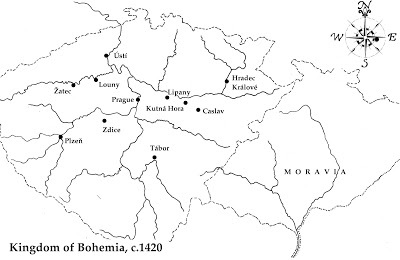

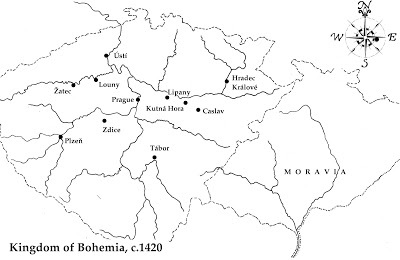

My good friend Martin Bolton has drawn a splendid map of Bohemia c.1420, which will be inside the paperback version of the book:

Soldier of Fortune (II) The Heretic is currently in the last stages of editing and will be available very soon. More details to follow soon...

A previous update on the book, including a brief account of Jan Zizka, can be read under the link below:

Hussites and Zizka

Fall of ConstantinopleCaptured at the final siege of Constantinople in 1453, Page is literally forced to sing for his supper (or rather, his life) by the victorious Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed the Conqueror: to save his neck from the executioner's blade, Page must tell a series of Arabian Nights-style stories for the sultan's entertainment. As an old soldier with a long military career behind him, Page chooses to tell stories from his own life - possibly a little exaggerated, but only he knows that.

Fall of ConstantinopleCaptured at the final siege of Constantinople in 1453, Page is literally forced to sing for his supper (or rather, his life) by the victorious Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed the Conqueror: to save his neck from the executioner's blade, Page must tell a series of Arabian Nights-style stories for the sultan's entertainment. As an old soldier with a long military career behind him, Page chooses to tell stories from his own life - possibly a little exaggerated, but only he knows that. Having already recited his first tale, based on his early career as a soldier in Normandy in the army of King Henry V, Page now recounts his time among the Hussites in war-torn Bohemia (part of the modern-day Czech Republic). The Hussites were followers of the martyred Bohemian preacher, Jan Hus, who was burned at the stake as a heretic in Constance in 1415. Hus was a radical who believed in cleansing the Catholic church of sin and corruption, and unsurprisingly hated by the Pope. After being thrown out of Prague University he wandered the country, preaching his ideals to the poor. He gained immense popular support, and when the news of his death reached Bohemia the people flew to arms to avenge him.

The Hussite armies were essentially made up of peasants, supported by a handful of nobles. Outnumbered and (supposedly) outclassed by the vast armies commanded by the Pope and his allies in Germany and Hungary, they should have been wiped out in a matter of weeks. Instead, thanks to innovative battle tactics and superb use of artillery, they won a series of unlikely victories against the odds. Thus the cream of the elite warrior nobility of Christendom was humiliated, time and again, by a few thousand commoners and some farm carts converted into gun-toting 'war wagons'.

The Hussite Wars, as they were called, raged for seventeen years. Page's story covers the years 1421-24, when the wars were at their height. For his sins, Page fights in the major battles and sieges, and witnesses some of the worst atrocities committed in a land riven by bitter civil conflicts, external invasions and extreme religious zealotry. During the course of the tale Page meets Jan Zizka, the famous Hussite general, meets a new love and loses old friends.

My good friend Martin Bolton has drawn a splendid map of Bohemia c.1420, which will be inside the paperback version of the book:

Soldier of Fortune (II) The Heretic is currently in the last stages of editing and will be available very soon. More details to follow soon...

A previous update on the book, including a brief account of Jan Zizka, can be read under the link below:

Hussites and Zizka

Published on April 25, 2016 03:10

March 30, 2016

Edward and Llewellyn, Part One

In August 1267 the ageing Henry III of England travelled with his court to the Welsh border at Montgomery. There he met with Llewellyn ap Gruffydd and granted the Welsh prince all he had long desired, including the Four Cantrefs of Perfeddwlad, the castle and lordship of Builth, and the greatest prize of all, formal recognition by the English crown of Llewellyn's title and supremacy over Wales.

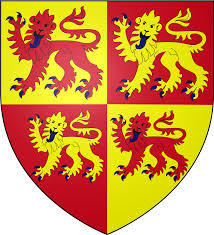

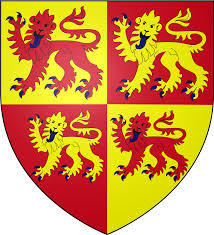

Llewellyn's arms as prince of GwyneddAmong the signatories to the deal, known as the Treaty of Montgomery, was Henry's eldest son, Edward. This was the first time Edward and Llewellyn had met in person, though they had stood on opposite sides in the recent baronial wars and fought over territory in the Welsh March. An army of mercenaries, sent into Wales on the young Edward's behalf, had been destroyed by Welsh forces at Coed Llathen in 1256. Edward's former lordship of Builth, taken by Llewellyn in 1260, was now officially given over to the prince. Yet despite this long history of antagonism the two men seemed to have got on rather well: two years later, Llewellyn wrote of his 'delight' at a second meeting with Edward. After Edward had departed for the Holy Land, Henry wrote back to Llewellyn, describing in warm terms the prince's friendship with his eldest son.

Llewellyn's arms as prince of GwyneddAmong the signatories to the deal, known as the Treaty of Montgomery, was Henry's eldest son, Edward. This was the first time Edward and Llewellyn had met in person, though they had stood on opposite sides in the recent baronial wars and fought over territory in the Welsh March. An army of mercenaries, sent into Wales on the young Edward's behalf, had been destroyed by Welsh forces at Coed Llathen in 1256. Edward's former lordship of Builth, taken by Llewellyn in 1260, was now officially given over to the prince. Yet despite this long history of antagonism the two men seemed to have got on rather well: two years later, Llewellyn wrote of his 'delight' at a second meeting with Edward. After Edward had departed for the Holy Land, Henry wrote back to Llewellyn, describing in warm terms the prince's friendship with his eldest son.

Thirteen years later, Llewellyn was fated to die in a ditch, slain by Edward's troops. His head was cut off and paraded on a spear through the streets of London, crowned with a wreath of ivy, in mockery of his princely status. Wales itself was conquered and occupied and turned into an English colony, while Llewellyn's regalia was broken up and sent to London, and his living descendants (children of his brother, Dafydd) locked up in convents or English prisons. How, from a promising start, did his relations with Edward collapse so dramatically?

The decline was slow, and far from inevitable. Relations were still amicable in 1269, when Edward intervened on Llewellyn's behalf in a violent territorial dispute with Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester. Edward risked much in doing so, for de Clare was one of the most powerful and volatile nobles in England. He had fought on both sides in the civil wars, and Edward needed his support (and cash) for the planned Crusade. De Clare was furious at Edward's judgement, and chose to stay and fight it out with Llewellyn rather than go east with his royal master.

Llewellyn's failure to prevent de Clare building his impressive castle at Caerphilly in Glamorgan might be seen as the turning point in the prince's fortunes. Up until now his career had been one long success story. Now the Marcher barons detected signs of weakness. In 1273 Humphrey de Bohun, heir to the earldom of Hereford, started to push his ancestral claims to the lordship of Brecon. He moved troops into the region, secure in the knowledge that the regent Edward left behind to govern England, Roger de Mortimer, was himself an aggressive Marcher baron and no friend of Llewellyn.