Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 232

November 8, 2016

EXPLORING ALBANIA

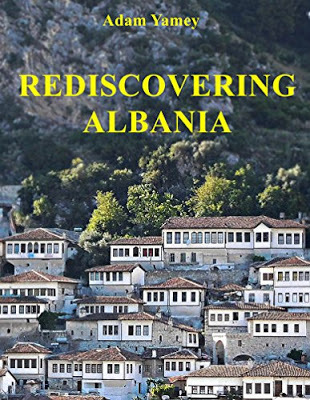

"REDISCOVERING ALBANIA"

A new book about Albania by Adam Yamey

Albanian people live all over the Balkans and in the Middle East, not to mention those who have migrated to Western Europe and the USA in the last two centuries. Subjects to a series of foreign rulers over the millennia, some of them now live in independent countries, which are governed by Albanians: the recently formed Republic of Kosova (‘established’ 2008), and the longer-established Republic of Albania (‘established’ 1912). Adam Yamey’s book, “Rediscovering Albania”, is about the latter, although some references are made to the former.

Adam, who has been interested in the Balkans – especially Albania – for many decades, first visited Albania in 1984, when the country was governed by a repressive regime headed by Joseph Stalin’s fervent admirer, the dictator Enver Hoxha (1908-1985). The country was then ‘hermetically’ sealed off from the rest of the world, even more so than North Korea is today. The only way for a tourist to visit Albania in 1984 was on a closely supervised guided tour during which the Albanian authorities did their best to ensure that the visitor only saw what they wanted. Their aim was to send tourists home with the impression that Albania was a ‘paradise’, which other countries ought to envy and emulate. In order to create that impression, the foreign visitor was not allowed to talk to, or otherwise communicate with, Albanian citizens; not allowed to stray from the tour group; not permitted to eat in the presence of Albanians; not allowed to take photographs of whatever interested him or her; not permitted to carry certain reading matter including religious works; and so on. Despite these restrictions, Adam came away having had an interesting view of the most beautiful country in the Balkans.

Enver Hoxha died in 1985, and was replaced by Ramiz Alia. Five years later, two years after the Berlin Wall was officially breached, Albania’s Stalinist dictatorship ended. For the first time since independence in 1912, Albanians began experiencing the closest they ever had to true democracy. In the beginning, it was not easy. During the early years of Albania’s post-Communist existence, there were many problems to be faced. For example: complex internal politics; the break-up of its neighbour, the former Yugoslavia; a civil war in 1997; Kosova’s struggle for independence.

In May 2016, Adam paid another visit to Albania. He and his wife hired a car and toured the country extensively – from the high mountains in the north to the Greek border in the south and the Macedonian border in the south-east. On this trip, Adam and his wife could: talk with any Albanian whom they met; travel wherever they wished; eat and drink with Albanians; take photographs without restrictions; carry whatever reading material they wished; and so on. They came away from the country with favourable impressions and happy memories.

During his latest trip, Adam kept a detailed travel journal. This formed the basis for writing “Rediscovering Albania”. The book charts Adam’s trip through Albania, providing personal anecdotes and observations that give the reader an idea of what to expect when visiting the country. But, there is much more. Wherever Adam went, he heard things from people, and saw sights that aroused his curiosity. On his return to London, he investigated what he experienced in detail. “Rediscovering Albania” describes Adam’s trip in the context of: Albania’s troubled history and vibrant present; the reports of earlier travellers (Francois Pouqueville, Lord Byron, Edward Lear, Edith Durham, and many others); and the opinions of Albanians, whom the author met during his journey. Also, the book includes comparisons of how the author found Albania in 1984 with what it is like today in 2016. The resulting text is an informative and entertaining introduction to one of Europe’s most fascinating, but undeservedly lesser-known, countries.

The book, which is available as a paperback and an e-book (Kindle format), contains two maps and many photographs.

As Adam took far too many pictures to be included in one book, he is posting them gradually on a Facebook page (which can be accessed and viewed by those who have no Facebook account). Visit: http://www.facebook.com/albanian2016images/

To buy a copy of the paperback: click HERE

To buy the Kindle: click HERE

Published on November 08, 2016 06:41

September 17, 2016

A bunker in south Albania

Bunker by Lake Ohrid, near Pogradec

Most of the defensive bunkers constructed in Enver Hoxha's Albania were in the form of hemispherical concrete domes (see illustration below).

Here, I describe an unusual one that I saw next to Lake Ohrid, just north of Pogradec.

Typical Hoxha era bunkers (near Lin)

Near the village of Memelisht (north of Pogradec), we examined the huge bunker on the lakeshore (illustrated above). It was like an elongated egg in plan. Part of it protruded into the lake, and the rest caused the road to curl around it. Its entrance faced inland. 2 gun slits faced north - one slightly towards the west and the other slightly towards the east. A third faced south towards Pogradec. I peered inside, and saw a central passage with doorways leading to 3 side rooms. The corridor was clean and painted white. A few discarded bottles lay on its floor. This ‘bunker’, which was so different from other bunkers that we saw in Albania, puzzled me. Valent at the hotel believed that it had been built by the Italians to control the road between Elbasan (and the north of Albania) and the south of the country as well as Greece. This seemed a reasonable explanation for its existence and positioning.Does anyone know exactly who built it. Was it the Italians, the Albanians, or someone else?Now, please visit: Adam Yamey's website

Published on September 17, 2016 02:28

September 11, 2016

M E T R O P O L I S

There are 2 places in London that remind me of some of the sets in Fritz Lang's film "Metropolis" (1927): the common parts (vestibules etc) of the Barbican Centre and the escalator hall of Westminster Underground Station ( rebuilt in 1999).

At Westminster there is an interchange between the Jubilee Line and the Circle/District Lines. The sub-surface Circle/District lines are separated from the far deeper Jubilee Line by a series of ecalators. The latter are housed in a huge concrete lined space. The whole ensemble is grey and gloomy, lit by lights that both illuminate and at the same time emphasise the gloomy nature of this futuristic collection of escalators, steel tubes, and other structural elements. I use the word 'futuristic' with reservation as this place resembles, as already mentioned, the sets of a film made back in 1927.

Full of human life, this interconnecting hall is rather inhuman - a collection of machines for moving hordes of people from A to B. It reminds me of factory assembly lines. Worth visiting because it is an extrordinary visual and psychological experience - and because it helps you to travel through the metropolis.

READ MORE OF ADAM YAMEY'S

WRITING

HERE

Published on September 11, 2016 03:33

August 2, 2016

PLAYING CRICKET IN ALBANIA

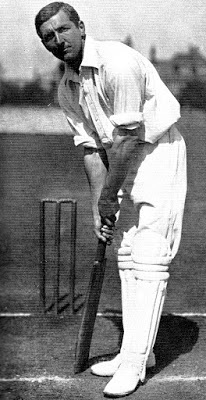

CB Fry (source: Wikipedis)

Here is an excerpt from Adam Yamey's soon to be published book "REDISCOVERING ALBANIA" ...

Albania's hero Skanderbeg (Picture by A Yamey)

My only criticism of the National Museum in Tirana was that it was poorly ventilated. After spending about 1½ hours looking around it, we returned to the enormous foyer, and slumped into 2 of the large comfortable armchairs located in the entrance foyer. These chairs reminded me of those which were provided, complete with lace anti-macassars, in the customs shed at the Han-i-Hotit Albanian border post, when I arrived there in 1984. One of the chairs in the foyer was occupied by a man, who looked as if he might have been from the Indian sub-continent. He was working on his lap-top computer. While I visited the museum’s shop, Lopa remained seated. At one stage, the man with his computer made a ‘phone call to his wife. Lopa, recognizing the man’s obvious Indian accent, asked him where he was from. He said that he was from the south of India, and was waiting for his son to return from cricket practice. We were surprised to hear that cricket was being played in Albania. Vijay told us that there was an Englishman in Tirana, who was trying to teach an Albanian rugby team to play cricket, and that there were plans to organise a cricket match between the locals and ex-patriates from the UK, Pakistan, India, and elsewhere. This match between the local Albanian Eagles and the international visitor’s team the International Lions was to be played in late June soon after we left Albania. The Eagles who were all out for 49, won by 1 run. Our friend Vicky was the 2nd highest scorer with 16 runs.Albania nearly became associated with cricket soon after gaining independence in 1912. The renowned British cricketer CB Fry (1872-1956), who was also a politician, was offered the throne of Albania in 1920, but declined it. A report in the Guardian newspaper published on the 12th August 2001 describes how the European Cricket Coach, Tim Dellor, first brought cricket to post-Communist Albania. The reporter concluded: “A seed has been sown in a dusty terrain. If it grows, could a Test match take place one day in Tirana?”. Well, the Test match is still awaited, but on the 26th May 2015, Albania hosted its first ever international match. It was between the Albanian Eagles, captained by Prince Leka II, Zog’s grandson, and the International Lions, captained by the English comedian Tony Hawks. The Albanian team won, and was awarded the Sir Norman Wisdom Trophy.[Norman Wisdom, by the way, is popular in Albania because his films were the only foreign films that were permitted to be screened in Albania whilst it was enduring more than 4 decades of Stalinist repression under its Communist dictator Enver Hoxha.]

READ MORE ABOUTBOOKS BY ADAM YAMEY by clicking HERE

Published on August 02, 2016 02:51

May 7, 2016

SHIFTY POLITICS IN SOUTH AFRICA

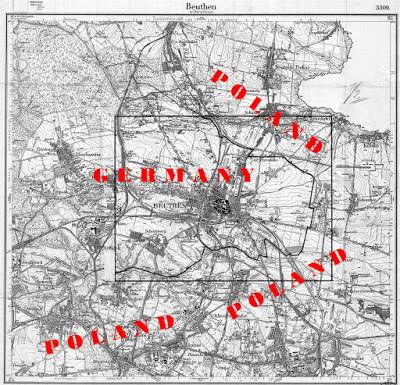

In 1862, when Adam Yamey's great-grandfather Franz Ginsberg was born, his birthplace BEUTHEN (now Bytom in Poland) was deep within German territory. After 1918 when borders shifted, Beuthen was still in Germany BUT ONLY JUST because it was surrounded on three sides by Poland which was no more than a mile from the city's heart.

While Franz Ginsberg was a Senator in the parliament of the Union of South Africa, legislation, inspired by the Minister of the Interior DF Malan (an architect of apartheid), was being formulated (in March 1930) that would severely restrict the entry into the country of Eastern European Jews. Franz Ginsberg was firmly against this.

One of Franz’s many objections was connected to the impermanence of Europe’s national borders. He said:“Considerable difficulties will arise with this Bill ... There have been perfectly new boundaries created in Europe since the war (i.e WW1), countries that formerly belonged to Germany have become, for instance, Polish ... there is Silesia too. My birthplace is in Silesia and I am very glad to think that I would not come under the ratio of prohibited countries (i.e countries, such as Poland, whose Jews were to become subject to a quota on immigration to South Africa), although that might have been the case if the boundary laid down in the Peace Treaty had been shifted a few miles...”

Sadly, the South African Government passed the Quota Act of 1930. DF Malan defended its passing. According to the issue of the JTA published in November 1931:"The Quota Act, he (i.e. Malan) declared, was introduced in the interests of the whole country, including the Jews. There was a feeling of unrest over the low type of immigrants coming from Eastern Europe, and the whole country demanded legislation to limit this immigration. The unrest threatened to develop into a feeling of hatred against the Jews, and as a result of the Quota Act this bad feeling has died down. “Cynically, Malan was presenting his anti-Jewish legislation as something that would benefit Jews already in South Africa. This was not long before South Africa’s version of the Nazis, the Greyshirts, started becoming really active.

Read more about how Franz tried to defend the rights of Eastern European Jews to enter South Africa, as well his fights for the rights of many of the less priviliged members of South African society in “Soap to Senate: A German Jew at the Dawn of Apartheid” by Adam Yamey. The book is available from Amazon and www.lulu.com

Visit www.adamyamey.com to discover more writing by Adam Yamey

Published on May 07, 2016 04:53

April 27, 2016

THE PRE-HISTORY OF APARTHEID

Senator Franz Ginsberg (1862-1936)

In the 1960s, my late mother used to mention her grandparents Franz and Hedwig, and often remarked that theirs were an odd pair of names. For a long time that was all that I knew about them. My late uncle Sven Rindl gave me an ingeniously designed family tree of our Ginsberg family many years ago, and I kept it as a curiosity. It assumed a great significance when, in about 2000, I began to become interested in the history of the families into which I was born. Soon after this, I learnt that Franz was a South African Senator and that he was held in high regard by my mother’s family. After investigating the lives of other members of my extended family, I began including Franz amongst those whom I researched. Several members of the extended Ginsberg family were kind enough to supply me with much interesting material, but at first I was unable to put them together to form a ‘big picture’ of Franz’s life. As I began to do so, I realised that not only was I discovering a great deal about his life, but also about a fascinating and important period during the history of South Africa.

I obtained a British Library Reader’s Ticket, and that was the key to unravelling Franz’s story. My great-grandfather Franz Ginsberg (1862-1936) left his birthplace in Prussia in 1880, and shifted to King Williams Town (‘King’) in the Eastern Cape of what is now South Africa. He lived there for the rest of his life. The British Library is home to a more or less complete run of one King’s newspapers, the Cape Mercury(the ‘Mercury’). When the newspapers were stored at Colindale, I used to drive there and spend several hours every Saturday morning leafing through the huge bound volumes of the paper. As I did so, fragments of the crumbling paper used to float down off the pages, which I imagine had hardly ever been looked at since they were printed in King and then bound by the library in London. I scoured every page from 1880 onwards looking for mentions of ‘Ginsberg’. Before 1885, there were no mentions of Franz because there was little reason for him to appear in the news. But, from 1885 onward both he and, to a lesser extent, his future brother-in-law the photographer Jakob Rindl began to appear at ever increasing frequency in the pages of the Mercury. For, it was in 1885, that Franz opened his own factory. It made matches. The match factory was followed by an ink factory, and then a candle factory, and later a soap factory.

Mentions of Franz in the Mercury became even more frequent after about 1890, when he entered local politics. First, he was elected a Town Councillor, then the Mayor for a while. Soon, Franz entered national politics, and became elected a Member of the Cape Parliament, a position that he held until 1910 when the Cape Colony and the three other colonies of southern Africa united to become ‘South Africa’. After unification, Franz became King’s member of the newly formed Cape Provincial Council. He remained on this until 1927, when he became the first elected Jewish Senator in South Africa. Franz’s name began appearing in the Mercury with ever increasing frequency until he became a Senator. After his ascent to the exalted position of Senator, he did not disappear from the pages of the Mercury, but mentions of him became less frequent because his civic duties in King occupied less of his time than the affairs of the Senate.

From 1885 onwards, the information that I gleaned from the pages of the Mercury, which is now stored in Yorkshire but made available in the British Library in Kings Cross, gave me a good idea of what Franz and his family were up to. The newspaper entries included detailed reports on the proceedings of the Town Council of King as well as what happened in meetings of other organisations, such as the town’s School Board, in which Franz participated actively for many years. From these reports, I began to build up a picture of how Franz functioned as a politician. The newspapers also included details of his comings and goings as well as a wealth of information about his and his family’s involvement in the life of King.

There are two other important sources of information about Franz, which I consulted. These were the reports of both the Cape Parliament and also of the South African Senate. Both of these publications reported the debates in the two legislative assemblies in great detail. The Cape Parliament reports recorded the debates as reported speech, whereas the Senate was reported more or less verbatim. Therefore, what is reported in the Senate debates is what the speakers actually said, rather than someone else’s summary. In the absence of any known recordings of Franz’s voice, what is preserved in the reports of the Senate’s debates is all that remains of the authentic voice of my great-grandfather.

In addition to the above mentioned, there was a host of other material that I consulted whilst preparing Franz’s biography. Some of this, including much interesting material about Franz’s diamond mining activities in German South West Africa (now ‘Namibia’) and his brother Gustave’s life, were from the National Archives of South Africa. Accessing this material remotely from the UK involved employing locals in South Africa to look up the documents (that I had identified in the archives’ on-line catalogue), and then photographing them to send to me. This was always most satisfactory. Books from the British Library and material sent to me by relatives provided more pieces to complete the jigsaw puzzle.

I have been researching Franz’s life for well over 10 years. Several times I tried to write his biography, but had to give up because although he achieved a great deal in many fields, his story did not seem to me to be of general interest. That was the case before I began looking in detail at what he did and said whilst he was a Member of the Cape Parliament, and then later a Senator in the Parliament of the Union of South Africa.

Franz was a Member of the Cape Parliament between 1905 and 1910. He was a Senator from 1927 until his death in 1936. Between 1910 and 1927, he was involved in provincial, rather than national, politics, representing King on the Cape Provincial Council. During the first 4 decades of the 20th century, much legislation was passed that diminished what few rights the non-Europeans ever possessed. One can safely say that this legislation paved or eased the way towards the establishment of apartheid in 1948.

Arriving in South Africa aged 18, Franz did not have a university education. His father Nathan was an accomplished academic. For religious reasons, as I explain in my book, Nathan had to turn down offers of academic positions in German universities. So, despite not having attended university it is likely that Franz was well-educated when he arrived in South Africa. When he was involved with national politics, he debated with politicians, many of whom had attained a high level of formal university education: lawyers, clerics, and so on. Yet, the reports of the debates in which he was involved demonstrate that Franz was easily able to hold his own with his highly educated colleagues in the Parliament and the Senate. Always an opponent of the Nationalists, he was able to see through the deviousness and disingenuousness of their arguments. And, being able to do so, he attempted to combat or at least to mitigate the unfair legislation that they were promoting. Sadly, he was one of a few lone voices crying out in the wilderness.

When I began to see what my investigations into Franz’s political life were revealing, I realised that writing about his life would result in something with greater interest than a simple biography. Franz’s biography opens a ‘window’ into the history of the evolution of apartheid.

Prejudice against non-Europeans in South Africa began as soon as the Dutch first dropped anchor in the waters lapping the Cape of Good Hope. During the 19thcentury, under British rule, things did not improve for the non-Europeans. By the beginning of the 20th century, ensuring the submission of the non-European population became an ever-increasing concern of legislators. The ending of the 2nd Boer war in 1902, and the desire to unify the 2 former Boer republics (the Orange Free State and Transvaal) with the 2 British colonies (Cape Colony and Natal) led to a further reduction in the political status of the non-Europeans. This was because in order to achieve unification, the British felt obliged to acknowledge, or at least not challenge, the firmly held views of the Boers that non-Europeans were to be regarded as inferiors with no rights at all.

Franz’s role in the politics of this interesting era was that of trying to ensure that non-Europeans were fairly treated. However, this is an oversimplification as I explain in my book. His approach was complex, and at times unusual. Trying to explain his activities to today’s readership in the context of his times was one of the challenges of writing his biography. I feel that this is what gives my narrative interest to a wider audience. One reader in South Africa has already written:“Your studious unravelling and compilation of Franz’s remarkable life … gave me a sense of the evolution of our country…”It is this ‘sense of the evolution’ of modern South Africa that I had hoped to convey when I published my biography of Franz Ginsberg, “Soap to Senate: A German Jew at the dawn of Apartheid.” (By Adam Yamey)

Available on Amazon Kindle and from www.lulu.com (paperback edition) by typing “Soap to Senate” in the appropriate places on these websites.

Published on April 27, 2016 15:30

Opening a window onto the pre-history of apartheid

Senator Franz Ginsberg (1862-1936)

In the 1960s, my late mother used to mention her grandparents Franz and Hedwig, and often remarked that theirs were an odd pair of names. For a long time that was all that I knew about them. My late uncle Sven Rindl gave me an ingeniously designed family tree of our Ginsberg family many years ago, and I kept it as a curiosity. It assumed a great significance when, in about 2000, I began to become interested in the history of the families into which I was born. Soon after this, I learnt that Franz was a South African Senator and that he was held in high regard by my mother’s family. After investigating the lives of other members of my extended family, I began including Franz amongst those whom I researched. Several members of the extended Ginsberg family were kind enough to supply me with much interesting material, but at first I was unable to put them together to form a ‘big picture’ of Franz’s life. As I began to do so, I realised that not only was I discovering a great deal about his life, but also about a fascinating and important period during the history of South Africa.

I obtained a British Library Reader’s Ticket, and that was the key to unravelling Franz’s story. My great-grandfather Franz Ginsberg (1862-1936) left his birthplace in Prussia in 1880, and shifted to King Williams Town (‘King’) in the Eastern Cape of what is now South Africa. He lived there for the rest of his life. The British Library is home to a more or less complete run of one King’s newspapers, the Cape Mercury(the ‘Mercury’). When the newspapers were stored at Colindale, I used to drive there and spend several hours every Saturday morning leafing through the huge bound volumes of the paper. As I did so, fragments of the crumbling paper used to float down off the pages, which I imagine had hardly ever been looked at since they were printed in King and then bound by the library in London. I scoured every page from 1880 onwards looking for mentions of ‘Ginsberg’. Before 1885, there were no mentions of Franz because there was little reason for him to appear in the news. But, from 1885 onward both he and, to a lesser extent, his future brother-in-law the photographer Jakob Rindl began to appear at ever increasing frequency in the pages of the Mercury. For, it was in 1885, that Franz opened his own factory. It made matches. The match factory was followed by an ink factory, and then a candle factory, and later a soap factory.

Mentions of Franz in the Mercury became even more frequent after about 1890, when he entered local politics. First, he was elected a Town Councillor, then the Mayor for a while. Soon, Franz entered national politics, and became elected a Member of the Cape Parliament, a position that he held until 1910 when the Cape Colony and the three other colonies of southern Africa united to become ‘South Africa’. After unification, Franz became King’s member of the newly formed Cape Provincial Council. He remained on this until 1927, when he became the first elected Jewish Senator in South Africa. Franz’s name began appearing in the Mercury with ever increasing frequency until he became a Senator. After his ascent to the exalted position of Senator, he did not disappear from the pages of the Mercury, but mentions of him became less frequent because his civic duties in King occupied less of his time than the affairs of the Senate.

From 1885 onwards, the information that I gleaned from the pages of the Mercury, which is now stored in Yorkshire but made available in the British Library in Kings Cross, gave me a good idea of what Franz and his family were up to. The newspaper entries included detailed reports on the proceedings of the Town Council of King as well as what happened in meetings of other organisations, such as the town’s School Board, in which Franz participated actively for many years. From these reports, I began to build up a picture of how Franz functioned as a politician. The newspapers also included details of his comings and goings as well as a wealth of information about his and his family’s involvement in the life of King.

There are two other important sources of information about Franz, which I consulted. These were the reports of both the Cape Parliament and also of the South African Senate. Both of these publications reported the debates in the two legislative assemblies in great detail. The Cape Parliament reports recorded the debates as reported speech, whereas the Senate was reported more or less verbatim. Therefore, what is reported in the Senate debates is what the speakers actually said, rather than someone else’s summary. In the absence of any known recordings of Franz’s voice, what is preserved in the reports of the Senate’s debates is all that remains of the authentic voice of my great-grandfather.

In addition to the above mentioned, there was a host of other material that I consulted whilst preparing Franz’s biography. Some of this, including much interesting material about Franz’s diamond mining activities in German South West Africa (now ‘Namibia’) and his brother Gustave’s life, were from the National Archives of South Africa. Accessing this material remotely from the UK involved employing locals in South Africa to look up the documents (that I had identified in the archives’ on-line catalogue), and then photographing them to send to me. This was always most satisfactory. Books from the British Library and material sent to me by relatives provided more pieces to complete the jigsaw puzzle.

I have been researching Franz’s life for well over 10 years. Several times I tried to write his biography, but had to give up because although he achieved a great deal in many fields, his story did not seem to me to be of general interest. That was the case before I began looking in detail at what he did and said whilst he was a Member of the Cape Parliament, and then later a Senator in the Parliament of the Union of South Africa.

Franz was a Member of the Cape Parliament between 1905 and 1910. He was a Senator from 1927 until his death in 1936. Between 1910 and 1927, he was involved in provincial, rather than national, politics, representing King on the Cape Provincial Council. During the first 4 decades of the 20th century, much legislation was passed that diminished what few rights the non-Europeans ever possessed. One can safely say that this legislation paved or eased the way towards the establishment of apartheid in 1948.

Arriving in South Africa aged 18, Franz did not have a university education. His father Nathan was an accomplished academic. For religious reasons, as I explain in my book, Nathan had to turn down offers of academic positions in German universities. So, despite not having attended university it is likely that Franz was well-educated when he arrived in South Africa. When he was involved with national politics, he debated with politicians, many of whom had attained a high level of formal university education: lawyers, clerics, and so on. Yet, the reports of the debates in which he was involved demonstrate that Franz was easily able to hold his own with his highly educated colleagues in the Parliament and the Senate. Always an opponent of the Nationalists, he was able to see through the deviousness and disingenuousness of their arguments. And, being able to do so, he attempted to combat or at least to mitigate the unfair legislation that they were promoting. Sadly, he was one of a few lone voices crying out in the wilderness.

When I began to see what my investigations into Franz’s political life were revealing, I realised that writing about his life would result in something with greater interest than a simple biography. Franz’s biography opens a ‘window’ into the history of the evolution of apartheid.

Prejudice against non-Europeans in South Africa began as soon as the Dutch first dropped anchor in the waters lapping the Cape of Good Hope. During the 19thcentury, under British rule, things did not improve for the non-Europeans. By the beginning of the 20th century, ensuring the submission of the non-European population became an ever-increasing concern of legislators. The ending of the 2nd Boer war in 1902, and the desire to unify the 2 former Boer republics (the Orange Free State and Transvaal) with the 2 British colonies (Cape Colony and Natal) led to a further reduction in the political status of the non-Europeans. This was because in order to achieve unification, the British felt obliged to acknowledge, or at least not challenge, the firmly held views of the Boers that non-Europeans were to be regarded as inferiors with no rights at all.

Franz’s role in the politics of this interesting era was that of trying to ensure that non-Europeans were fairly treated. However, this is an oversimplification as I explain in my book. His approach was complex, and at times unusual. Trying to explain his activities to today’s readership in the context of his times was one of the challenges of writing his biography. I feel that this is what gives my narrative interest to a wider audience. One reader in South Africa has already written:“Your studious unravelling and compilation of Franz’s remarkable life … gave me a sense of the evolution of our country…”It is this ‘sense of the evolution’ of modern South Africa that I had hoped to convey when I published my biography of Franz Ginsberg, “Soap to Senate: A German Jew at the dawn of Apartheid.” (By Adam Yamey)

Available on Amazon Kindle and from www.lulu.com (paperback edition) by typing “Soap to Senate” in the appropriate places on these websites.

Published on April 27, 2016 15:30

April 24, 2016

The genesis of apartheid in South Africa

The book "SOAP TO SENATE: A GERMAN JEW AT THE DAWN OF APARTHEID" by Adam Yamey is the story of an enterprising man. His life was dedicated to improving the lot of those who were less fortunate than him, as well as advancing his own family. He lived in South Africa during the gestation period of apartheid that was completed a dozen years after his death. Had there been more men who acted as he did, it is possible that apartheid might never have seen the light of day.

The man was my great-grandfather, the late Senator Franz Ginsberg (1862-1936).

At the age of eighteen, he migrated from Germany to King Williams Town in the eastern part of the Cape Colony (in what is now ‘South Africa’). During the 56 years that he lived there, he served his adopted country and its people generously. He was a ‘Victorian’ man. However, he stood out s being unusual amongst his contemporaries because he tried to counter the relentlessly racist tide in South African governmental policy-making - something that he was able both to observe first-hand and also to criticise in the positions of public office that he occupied for many decades.

Ten years after Franz’s death, Steve Biko, the black anti-apartheid activist, was born in the King Williams Town (‘King’). This man, a founder of the Black Consciousness Movement, was callously murdered by the South African apartheid government in 1977. They were terrified by him, his ideas, and his powerful influence. In 2003 when I visited the Steve Biko Foundation headquarters in King, I was shown a room that contained a number of commemorative wall plaques. Each of these celebrated someone who was considered to have been important by the Foundation. With the exception of one, all of the plaques commemorated black Africans involved in the struggles for their rights. The exception was one to remember my great-grandfather. At first sight, there would appear to be little to link a German Jewish immigrant, such as Franz was, with a martyr to the cause of freedom of the black people in South Africa. However, there is a connection. Biko was born and also lived in an African ‘township’ in King Williams Town. Steve’s birthplace, Ginsberg Township, was named in honour of my great-grandfather. Franz wanted it built to give his African workers better housing.

Franz arrived in South Africa with a high-school German education, and then began working as a photographer’s assistant. Within a few years, he became one of King Williams Town’s leading industrialists. Soon after that, he entered local, and then, national politics. In 1927, he was awarded a great honour: he was elected a Senator in the South African Parliament, the first Jew to be so elected.

This book describes the life of my great-grandfather, who left Germany both to seek his fortune and also to escape religious prejudice. In his adopted country, South Africa, he found himself privileged to be a white man accepted by other Europeans on the basis of merit rather than religious beliefs. However, being a man of conscience with great sympathy for his non-European neighbours, he tried to strike a moral balance between easing the lot of his severely disadvantaged non-white compatriots and safeguarding the superior advantages of the white man. Franz exemplified the words of the famous Jewish scholar Hillel the Elder: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? But if I am only for myself, who am I?”

The book is fully illustrated with photographs and maps

"SOAP TO SENATE: A GERMAN JEW AT THE DAWN OF APARTHEID"

IS

AVAILABLE IN PAPERBACK by clicking HERE

AND AS A KINDLE by clicking HERE

Or just type "SOAP TO SENATE" in the search box of either Amazon (your local regional site) or lulu.com

Published on April 24, 2016 04:30

December 20, 2015

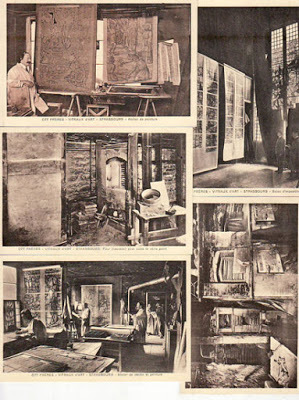

STRASBOURG or STRASSBURG? - from ALSACE to PONDICHERRY

In late November, early December 2015, I visited the southern Indian coastal city of Pondicherry (‘Pondi’). Until 1954, this small place on the coast of the Bay of Bengal was a French colony. Now, it is an Indian Union Territory. When the French left in 1954, the ethnically Indian (mainly Tamil) inhabitants of Pondy were offered the opportunity of becoming French citizens. Many accepted. So, at present many of the inhabitants of Pondi are still French subjects, and enjoy the benefits associated with this status. Apart from architecture, there are many left-overs from Pondi’s days as a French colony. For example, policemen wear red képis on their heads and street signs are bilingual: Tamil and French.

There is a church close to Pondy’s railway station, Basilique Sacre Coeur (Sacred Heart Basilica). This is an airy Gothic revival edifice, which was built between 1902 and 1907, when the first mass was held in its eastern wing. The church was completed by 1908

My interest was immediately heightened. Strassburg was the German name for the now French city of Strasbourg. However in 1908, the city was under German administration. It had been since France was defeated in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and was to remain so until the end of the First World War (‘WW1). “OTT Fres” was, I assumed, an abbreviated form of OTT Frères, which I guessed (correctly) was the manufacturer of the stained glass.

On my return to the UK, I looked up ‘OTT Frères’ on the Internet, and was gratified to discover that such a company existed. OTT Frères (OTT brothers) was a company of stained glass painters based in in Strasbourg/Strassburg. They furnished windows for a variety of buildings (churches and other public buildings) in Alsace, especially in the city of Strasbourg/Strassburg during the first two decades of the 20th century

It is of interest to note that the (French) builder of the church in Pondy chose to commission windows from a company in enemy (German) occupied Alsace, but he did. However, not all of the windows in the church were made by Ott Brothers. Some, which seemed newer in design than those made by Ott and not nearly as finely executed, were manufactured by a company in Grenoble.

Strasbourg/Strassburg, like Pondicherry, changed hands. The city remained under German control for about 47 years, whereas Pondy remained under French control for far longer: from 1674 until 1954.

I have some French relatives living in present day Strasbourg. They have been there for several generations, having moved there from southern Germany at the end of the 19th century. When Alsace-Lorraine was occupied by the Prussians in 1870-71, another of my many ancestral relatives, quite unrelated to those of my family who live in Strasbourg today, was a soldier in the Prussian Army. This man was Leo Ginsberg (1845-1895), who was born in Prussia (Breslau) and was the half-brother of my great-grandfather the South African Senator Franz Ginsberg (1862-1936). Leo settled in the occupied Alsatian city. One of his grandchildren told me that when Leo married, he and his wife were required by law to purchase a set of china dishes from the royal Prussian porcelain factories. Leo had 4 children, all of whom migrated to South Africa, where they lived in King Williams Town in which their uncle Franz had settled in 1880.

We would never have visited Sacre Coeur had I not wanted to see Pondy’s railway station, which turned out to be a bit of a disappointment visually. Since the church is across the road from the station, we felt that we should take a look at it, and I am glad that we did, as doing so revealed a tiny aspect of colonial history.

NOW VISIT

ADAM YAMEY'S

WEBSITE:

http://www.adamyamey.com

FOR SOME MORE WORKS OF INTEREST

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilic... http://www.archi-wiki.org/personnalit... http://www.hoogeduinpostcards.com/web... http://www.cc-porte-alsace.fr/tourism... & http://www.culture.gouv.fr/public/mis... https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?s...

Published on December 20, 2015 08:54

December 14, 2015

BANGALORE UBER OLA

I first visited the south Indian city of Bangalore, now called ‘Bengaluru’, in January 1994. About 30 years before that, one of London’s first ‘minicab’ companies, Meadway Cars, began carrying customers all over London. The minicabs were the first new addition to the existing modes of public carriage in London for many years. Prior to their introduction, the public could travel by bus, tube train, or in black taxis (‘Hackney Cabs’) – trams and trolleybuses had been phased out by 1964.

The options for public carriage in Bangalore in 1994 were: busses (often looking very battered), auto-rickshaws (three-wheeler ‘autos’), and private hire cars. The latter were operated by smallish private firms, and could be hired in advance for varying lengths of time and distance: for example for 4 hours and 60 Km; they were not metered. These cars were in general unmarked.

Gradually taxi companies such as ‘Easy Cabs’ hit the city’s crowded thoroughfares. Generally, they were uncomfortable Maruti vans, but they were metered. Unlike autos, they could not be hailed from the street; they had to be ordered by telephone.

The 21st century has seen not only the construction - albeit exceedingly slowly - of a metro system in Bangalore, but also the introduction of two new kinds of four-wheeler taxi. One of these is the so-called ‘Airport Taxis’ operated by companies such as Meru and KSTDC, and the other is the ‘computerised’ taxis such as are operated by the international company Uber, and the Indian company Ola. All of these new cabs may be ordered using ‘applications’ downloaded onto ‘smartphones’, and there the problems begin.

Before going any further, I must emphasise that I have not encountered any problems ordering Meru Taxis (by telephone.) However, this cannot be said of Ola and Uber, which I have attempted to order using their slick ‘apps’. On opening the Ola or Uber ‘app’, a GPS mechanism attempts to locate the potential passenger, and then displays a map showing where the nearest Uber or Ola vehicles are located, and also how long it is likely for each cab to reach the customer. Sadly, this is where things begin to go wrong. A cab which might be stated as being 5 minutes away might take as long as 30 minutes to reach you, or may not reach you at all! This is either because the GPS has not located the passenger accurately enough or because - and this is most likely - the driver is unable to comprehend the workings of the GPS system, or both. Whilst driver and passenger are attempting to meet, the former makes innumerable ‘phone calls to the latter, often adding to the confusion and frustration of the passenger.

If and when the cab (Ola or Uber) eventually arrives, the passenger should not begin to relax. Despite the fact that the cabs are fitted with devices to enable the driver to navigate from A to B, some drivers seem unable to benefit from them. And, as many of the drivers we encountered seemed to be ignorant of Bangalore’s geography, what should have been a relaxing trip becomes stressful because the passenger needs to navigate and issue instructions to the driver. So far, I have yet to be impressed by Ola and Uber. For long distances, I would recommend the slightly more expensive Meru cabs. For journeys within Bangalore, there is no substitute for the somewhat uncomfortable, yet remarkably nippy autos. On the whole, the auto drivers know their way around Bangalore, and if they don’t they sidle up to another auto and make enquiries.

It might be early days for Ola and Uber in Bangalore and that with the passage of time, they will live up to the optimistic expectations of so many Bangaloreans and others who have begun to make use of them and are currently putting up with their defects.

Visit

http://www.adamyamey.com

to read more by Adam Yamey

Published on December 14, 2015 09:39