Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 230

May 6, 2017

Remembering the Holocaust in Harringey

Bruce Castle Garden of Remembrance

In the grounds of Bruce Castle, about which I will write in the future, there is a small fenced-off Garden of Remembrance. It is an attractively designed memorial to the victims of the Holocaust perpetrated by the Nazi Germans and their sympathisers.The garden was created by young offenders as part of their rehabilitation. Apart from a small plaque with gold letters carved into a piece of black stone, there is a sculpture made from six wooden railway sleepers.

Bruce Castle Garden of Remembrance

They stand vertically in a circle. Each one is supposed to represent one of the six million Jews killed in the Holocaust. And, each one has a single name carved on it. These six names are the first names of the six offenders who created this moving memorial. Behind that at the edge of the garden furthest away from the Castle, there is another sculpture (by Paul Margetts and Claudia Holder) representing prison bars and barbed wire.

Bruce Castle Garden of Remembrance sculpture

Part of the garden was redesigned to commemorate the life of Roman Halter (1927-2012), a Jewish Holocaust survivor who was born in Lodz, Poland. After the Second World War, Roman came to England where he became an architect, and then later a painter and sculptor. He lived in the Borough of Haringey, where this peaceful yet moving memorial garden is located.

Bruce Castle Garden of Remembrance: information notice

Remembering the Holocaust in Harringey remains copyright of the author ADAMYAMEY, a member of the travel community Travellerspoint.

Post tags: london poland holocaust harringey

Comment on this entry | Tweet this | Your own free travel blog | More Travellerspoint blogs

April 23, 2017

MONKS and NUNS, MARX and LENIN

Many years ago, in the 1980s, I was invited to join a friend for lunch at a trendy restaurant in Clerkenwell Green. A mutual friend joined us. We ordered our meal. When it arrived, there was far more empty space on the plate than food. There was a tiny piece of meat a little larger than a postage stamp, a floret of broccoli, and three minute boiled potatoes that had been whittled down to produce tiny whitish spindles. This was ‘nouvelle cuisine’, and entirely unsatisfactory. When the bill arrived, we discovered that we were being charged £25 each for these meagre, unwholesome offerings. Our mutual friend and I looked at our friend, who had suggested the restaurant. She, noticing our shocked expressions, settled our bills. I am afraid that this experience prejudiced me against Clerkenwell.

A recent visit to the area has killed my prejudice against it, and kindled a great enthusiasm.

Clerkenwell Green

Clerkenwell, which is now in the Borough of Islington, covers an area that includes: Farringdon Road, Goswell Road, Clerkenwell Road, Hatton Garden, and Smithfield Market (at its southern edge). I will confine my essay to the area around Clerkenwell Green.

The name ‘Clerkenwell’ is derived from the Old English words meaning ‘Clerks’ Well’. Remains of the well may be seen inside Well Court on Farringdon Lane. The formerly rustic Clerkenwell Green came into existence in the 12th century following the establishment of two neighbouring ecclesiastical institutions: The Knights Hospitallers’ priory of St John and, to the north-west of that, the Augustinian nunnery of St Mary. After the dissolution of these institutions by King Henry VIII between 1536 and 1541 , land was sold off and buildings had begun appearing around the green. A map drawn in 1560, shows what is now Clerkenwell Green close to the outer edge of the rest of London. The historian Riddell (see below) wrote:

“By the middle of the sixteenth century Clerkenwell had graduated from being a village on the outskirts of London, which had grown up round two monastic foundations, to being a suburb of the City”.

By the 18th century, Clerkenwell Green and its surroundings had become absorbed by the growth of London. A 1750 map shows that Clerkenwell Green and its associated buildings were on the northern edge of London. By 1860, the area could no longer be considered as being on the edge of London, but deeply within it. However, even today Clerkenwell Green, which is close to busy London thoroughfares, gives rise to feelings of its former rural past.

Clerkenwell Road: old Holborn Union offices

I will describe the area as I visited it recently, beginning with a building on Clerkenwell Road on the corner of Britton Street. This elegant red brick building decorated with neo-classical features such as pilasters and triangular pediments bears the words ‘Holborn Union Offices’ above the date 1886. Now converted into flats, this building, designed by the architectural firm H Saxon Snell and Sons, used to house the administrative offices and medical and ‘out-relief ‘departments for the Holborn Union Board of Guardians. The Board administered the Holborn Poor Law Union, which was established in 1836, a precursor of the Welfare State that tried to alleviate the lot of poor people. And, in the 19th century, Clerkenwell had of people living in squalid conditions close to, or below, the poverty line.

Across the busy Clerkenwell Road almost opposite this building, a short road leads into the southwestern side of Clerkenwell Green. Entering the Green with its trees and picturesque buildings is like stepping out of the city and into a village green.

Clerkenwell Green: The Old Sessions House

Covered in scaffolding and just visible through it, there stands a building that used to be the Middlesex Sessions House. This court house, standing at the west end of the Green, was built in the last two decades of the 18th century. The Sessions House replaced the nearby Hicks Hall that dated back to 1611, and served many of the roles played by today’s Old Bailey. The court buildings figure in Charles Dickens novel “Oliver Twist”, in which they are referred to as ‘Clerkinwell Sessions’. It was conveniently located to a nearby prison (see below). The current building was used as a court until 1921. Now, the building is being developed to join Clerkenwell’s already large population of eateries and bars (see: http://theoldsessionshouse.com). I look forward to visiting the building when it has been restored.

Marx Memorial Library

Close to the Sessions House on the north side of the Green, there stands a building, number 37a, with a revolutionary past (and, who knows, maybe also a future). Karl Marx (1818-1883) lived in London between 1849 and 1850 (but not in Clerkenwell). His memory lives on in Clerkenwell Green at the Marx Memorial Library at number 37a, which was established in 1933 to celebrate the golden anniversary of his death. I have visited this centre of socialist study and education once, on a London Open House Day (see: www.openhouselondon.org.uk/). We were shown around the library and, also, the Lenin Room. Long before the establishment of the library, Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924) worked in this building in 1902 and 1903, supervising his revolutionary newspaper ‘Iskra’. The so-called Lenin Room, which houses much of the great man’s memorabilia is possibly not the exact place in the building where he worked.

When we were shown around the Marx Memorial Library, we were taken into its basement where books and other parts of the collection are stored. The basement contains remains of subterranean mediaeval structures, 15th century vaults that lead into tunnels. We were told by our guides that these tunnels might very possibly have connected the former nunnery of St Mary with the nearby former Priory of St John. If this was the case, one might wonder why they were built.

Before becoming used as the Marx Memorial Library, the building housing it was associated with the radical activity that pervaded Clerkenwell during much of the 19th century. Clerkenwell Green itself, being one of the few open spaces in the area, was the site of open-air rallies or meetings, both for radical and religious causes. Evangelical clerics held vast outdoor meetings to attempt to bring Christianity to the poor of the area, and left-wing groups attempted to rouse the people, often beginning protest marches in the Green. Clerkenwell Green became the 19th century’s equivalent to the later Hyde Park’s ‘Speakers’ Corner’. Number 37a housed first the radical ‘London Patriotic Club’, and then later the socialist ‘Twentieth Century Press’, before it became the Marx Memorial Library.

Clerkenwell Green: Crown Tavern

Feeling thirsty already? Then, help is at hand in the form of the nearby Crown Tavern. This pub might well have had Leninist connections. First established in the 1720s, the present pub is in a building that dates from about the beginning of the 19th century. Many believe that the young Joseph Stalin met Lenin in this pub in 1903. But not everyone shares that belief (see: http://sarahjyoung.com/site/2011/01/1...). While Lenin was in London in 1902 and 1903, Stalin was not. Stalin first visited the city in 1907, along with other Russian revolutionaries including Lenin, whom he first met in Finland in 1906.

St James Church viewed from Clerkenwell Green

The southernmost stretch of the winding Clerkenwell Close (‘close’ as in ‘cathedral close’ or abbey precincts) leads from the Green towards the west end of St James Church, which is well-worth visiting. A board close to its entrance informs that there has been a church on this spot since 1100 AD. To enter the present church, which dates back to 1792, it is necessary to ring a doorbell. When I visited it, I bought a copy of a most interesting book about the church “A History of The Church of Saint James Clerkenwell” by N Ridell (published 2016). This is full of information about both the church and the area surrounding it.

St James Church: west front

The present church stands within the ‘footprint’ of an older, larger one that was demolished (because it was falling to pieces, and could no longer be repaired) in order for the new one to be built. The older, demolished church had its origins as the chapel for the Nunnery of St Mary. The north side of the older church was attached to cloisters, which still existed as late as 1786. After the dissolution of the monasteries, much of the nunnery was destroyed and the land on which it stood was sold for housing and other purposes.

There is much that could be written about the history of the St James Church, but I will confine myself to a few things that I found interesting when I visited it. Before doings so, I will mention that Clerkenwell was a parish in which certain residents (the wealthier ones!) chose their church officials by election. Choosing someone to fill the highly-prized position of vicar was often associated with much public disorder. Prior to the later 19th century, much administration of the parish – both religious and secular – was carried out by a church-based committee, the ‘Vestry’. Members of the Vestry had many opportunities to enrich themselves. I will say no more.

The west end of the church consists of three interconnected lobbies. Both the northern and the southern ones have lovely curving staircases leading to the church’s upper storeys. The southern lobby, which I entered first, has several well-preserved memorial plaques on its walls, including an elaborately sculpted one for Thomas Crosse, who died aged 49 in 1712. He did much good work for the poor children of the parish, including founding a school.

St James Church: bell ringing feat

The nave of the church is entered from the central lobby. This lobby contains two memorials that interested me. One of them commemorates the 8th of December 1800, when eight young men managed to ring a complete peal of 5040 changes on the church’s steeple bells. They achieved this remarkable feat in three hours and 15 minutes. Ridell records that the 19th century bell-ringer G Morris was able to ring a peal on the eight bells on his own, with the bell-pull cords fixed to both of his hands and feet. The other memorial relates to a disaster that occurred on Friday the 13th of December 1867.

There were several prisons near to Clerkenwell Green in the 19th century. One of them was the Clerkenwell House of Detention (or Middlesex House of Detention) on Bowling Green Lane, very close to St James Church (and to the Middlesex Sessions House, where many of the inmates had been tried). In December 1867, several Fenians (revolutionary Irish nationalists) were being held in the prison. Some of their comrades planned to rescue them by breaching the wall of the exercise yard during the prisoners’ exercise break. A barrel of explosives was placed by the wall, but the prison authorities, having caught wind of the plot, cancelled the exercise session. The explosives were detonated on the 13th of December, causing much damage to people in the neighbourhood. The memorial in the church relates that 15 people were killed, 40 were injured, and 600 families suffered material loss. The large number of families reflects the overcrowded living conditions that had developed in Clerkenwell during the 19th century, making it one of the most deprived districts in London.

St James Church: Lion and Unicorn above entrance to nave

A beautifully sculpted Lion and Unicorn (dated 1792) recline on the pediment above the entrance to the body of the church. The rectangular body of the church is light and airy. It has a curved first floor gallery and fine stained glass windows above the high altar at its eastern end. The pale Wedgewood blue ceiling is decorated with delicate stucco designs.

St James Church: organ and ceiling

The organ on the first-floor gallery is flanked by a pair of incomplete second-floor galleries, remains of what had once been complete galleries like the one below it. At the western end of the church on both sides of the central entrance doors, there are boxed pews, one of which was labelled ‘Church Officers’ Pew’. These are the last of the original box pews that formerly filled the church, and were replaced by the present more open-plan pews sometime in the 19th century.

St James Church: Church officers' box pews

A small garden to the west of the church affords a good view of the tower and steeple with its white stone and brick facing and an old clock. The church is surrounded by green open spaces, some of which were part of the original churchyard. A part of these to the north of the church must have once been the site of the garden that used to be enclosed in the former nunnery’s cloister.

Tree sculpture near St James Church. "Spontaneous City"

One tree to the east of the church contains a curious modern sculptural work, which looks like a cluster of miniature wooden bird houses wrapped around the tree’s branches. This was installed in 2011 by London Fieldworks.

Clerkenwell Close Challoner House

Following Clerkenwell Close away from the Green, we come across a newish building called ‘Challoner House’. The original house bearing this name was built on this site in about 1612 for Sir Thomas Challoner, a courtier and naturalist, and tutor to the Prince of Wales. The present Challoner House stands beside a huge Peabody Estate that extends northwards to Bowling Green Lane and westwards almost to Farringdon.

Clerkenwell Close Peabody doorway

Clerkenwell Close Peabody Buildings

The Peabody Trust built the estate in 1884 following the passing of new housing legislation in 1875. The original estate consisted of 11 blocks of flats built around a central court yard. Each of the blocks had a laundry room on their top floors, but no communal bath houses.

Clerkenwell Close Peabody Trust buildings

Clerkenwell Close Peabody courtyard

George Peabody (1795-1869) was born into a poor family in the USA. In 1837, already a successful businessman and banker, he came to London. He became the ‘father of modern philanthropy’. His Trust begun in 1862, which continues today, financed, amongst many other things, the construction of decent housing for “artisans and labouring poor of London”. Noble as was this venture in Clerkenwell, it involved the demolition of slums that housed many poor people. Many of these people were too poor to afford the albeit modest rates (rents) charged by the Peabody Trust for their superior dwellings. This resulted in many of former the slum dwellers having to squeeze into the remaining, already overcrowded, disgusting slums in the area.

Clerkenwell Close and The Horseshoe pub

Across the Close from the barrack-like, somewhat forbidding looking Peabody buildings there is a quaint corner-sited pub ‘The Horseshoe’. It existed by 1747, and stands close to a large building that was built between 1895 and 1897 as the ‘central stores of the London School Board’.

Former London School Board stores

Old notices above the street-level doors of the building, such as ‘Needlework Stores’, ‘Furniture Dept.’, and ‘Stationery Dept.’, remind the passer-by of its original purpose. Unfortunately, as soon as it was opened, it was found to be too small, and additional premises had to be found nearby.

Former London School Board stores: modified internal courtyard

Former London School Board stores: modifiedentrance

modified interior]In 1976, the premises were converted to house craft workshops, the ‘Clerkenwell Workshops’. In 2006, MAK Architects gave the building a beautiful ‘make-over’. This can be enjoyed by entering the courtyard within the building via an attractive, gently sloping central passageway.

Old Hugh Myddelton School entrance Clerkenwell Close

Almost opposite the Clerkenwell Workshops on the east side of the northernmost stretch of Clerkenwell Close, I spotted an old white stone entrance arch that had the words ‘GIRLS & INFANTS’ carved on its lintel. This was once an entrance to the Hugh Middleton School that opened in 1893. The school was built on part of the site that had been occupied by the prison, which had been attacked by the Fenians a few years earlier (see above). The prison was closed in 1885-1886, and then demolished. The main building of the school with spectacular sloping tiled roofs, which is has been used as a block of flats since 1999, was designed by the school board’s architect TJ Bailey. Part of this property’s perimeter wall is all that survives of the former prison. The school, which had been regarded as a ‘model school, was closed in 1971. One of its better-known pupils was the popular 1930’s and ‘40’s band-leader Geraldo (Gerald Walcan Bright: 1904-1974). Geraldo was not the only famous musician in Clerkenwell (see below).

Sekforde Street opposite John Groom's New Crippleage

Seckforde Street, which begins near St James Church, attracted me both because of its name and, also, its attractive buildings. Its name derives from that of Thomas Seckforde (1515-1587), a lawyer and courtier in the Court of Elizabeth I, who:

“bequeathed a part of his Clerkenwell estate … to endow almshouses in the town of Woodbridge in Suffolk.” (see: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/surv...).

Seckforde Street was laid out in the late 1820s. It cut across what had been one of the poorest parts of Clerkenwell.

Corner of St James Walk and Sekforde Street: former John Groom's New Crippleage 'factory'

A wedge-shaped building standing where Seckforde Street meets St James Walk at an acute angle has a certain elegance and some antiquity. Its main entrance at its apex is surmounted by a circular tower-like structure. This building was once part of ‘John Groom’s Crippleage’ (being a shortened version of ‘John Groom’s Crippleage and Flower Girls Mission’). Born in Clerkenwell in 1845 (died 1919), Groom, an engraver, became a philanthropist concerned with the plight of the blinded and crippled girls who eked out a living selling flowers on Farringdon and sprigs of watercress in Covent Garden. His charity enabled the girls to be fed and clothed properly, as well as housed. The building at the corner was built to the designs of W H Woodroffe and E Carritt between 1908 and 1910 to be used as a factory and warehouse for Groom’s ‘Watercress and Flower Girls’ Christian Mission’. The factory produced, amongst other things, cotton roses for the first Alexandra Rose Day in 1912. Between the 1930s and 1950s, the building was occupied by the tobacco company Gallaher’s. Now, it is used to provide office space.

Some of the existing original 19th century houses on Seckforde Street opposite the former factory, were used to provide protective housing for girls rescued by the Crippleage Mission.

Jerusalem Passage: Thomas Britton lived and worked here

Jerusalem Passage is a few steps away from the southern end of Seckforde Street. On the corner of the Passage and Aylesbury Street, a building bears a plaque to the memory of the ‘Musical Coalman’. He was Thomas Britton (1644-1714), a local charcoal merchant. Successful as a coalman, Britton was blessed with a fine singing voice and a superior intellect. He built his own library and set-up a concert hall in his Clerkenwell premises, where the plaque is affixed today. His concert hall was furnished with a harpsichord and a small organ. He attracted many of the finest musicians of his day, including JC Pepusch and GF Handel, to play in his concert hall. In addition to his commercial and musical achievements, Britton became an accomplished chemist and a highly respected, serious bibliophile – well-known to leading collectors of books and manuscripts. Even though he achieved a fine reputation in the literary, intellectual, and musical worlds, Britton continued to work as a ‘coal man’ until his death.

Priory Church of St John: garden

Jerusalem Passage leads southwards into St Johns Square, which stands on the large piece of land that was once occupied by the Priory of the Order of St John, the ecclesiastical neighbour of the former Nunnery of St Mary. In the 11th century, a hospital was set up in Jerusalem to give assistance to pilgrims. The men and women who staffed this were known as the ‘Hospitallers’. With the arrival of the Crusaders in the Holy Land, the Hospitallers became a religious order recognised by ‘The Church’. They became known as the ‘Knights of the Order of St John of Jerusalem’. In about 1140, a priory was built in Clerkenwell by the Knights. It was their London headquarters. When King Henry VIII broke with the Church in Rome, the Order was dissolved, and much of the priory demolished. Many years later in 1888, Queen Victoria granted ‘Order of St John in England’ a Royal Charter.

Gateway to Order of St John

Gateway to Order of St John

The Priory Church of the Order of St John can be entered from the Square. The present structure, which is much smaller than previous incarnations of this church, the first of which dated back to the 12th century, was badly damaged by bombing in 1941. Now restored, it stands on the site of the chancel of the much larger 15th century church. The crypt of the present church, which can occasionally be visited by members of the public, dates to the 12th century. South of the present church, there is a modern cloister with a lovely garden, where anyone can sit and rest.

Order of St Johns Museum

Not much else remains of the priory except the fine 16th century gateway south of Clerkenwell Road. During the 18th century, this building was used briefly as a coffee house, which was run by the father of the famous artist Hogarth. Today, it houses offices and meeting halls of the Order of St John on its upper floor, and a well-laid out museum on its ground floor. It illustrates not only the fascinating history of the Order but also the good work it has done over the centuries. Amongst its many exhibits, there is a painting, which might well have been executed by the great Italian artist Caravaggio.

Lawson Ward and Gammage Ltd

Jewellery and watch-making were amongst the many crafts practised in Clerkenwell. The jewellery firm of Lawson Ward & Gammage Ltd was founded in the area in 1861. There are still some descendants of the founders working in the firm. Although their current workshops are now in Hatton Garden, a clock bearing their name projects from a building in Berry Street, to the east of Clerkenwell Green.

Sutton Arms pub

Further along Berry Street on a corner site, there stands the Sutton Arms pub. This hostelry was rebuilt in 1897, but was in existence at least as early as 1848.

Northburgh House designed by Cubitt & Co Ltd

Even further along Berry Street at the corner of Northburgh Street, there is a well-restored, elegant red brick building, Northburgh House. Standing between Berry Street and Pardon Street, this former warehouse was designed and constructed by William Cubitt & Co., who also built well-known buildings including Fishmongers’ Hall, Covent Garden market, Paxton’s Crystal Palace at the Great Exhibition of 1851, and the former Euston Station (see: http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/W._Cubit...). The warehouse was built in 1893-4 for Edward Saunders, a paper-bag manufacturer. Today, the refurbished building is home to various companies.

Goswell Road Graffiti

My ‘tour’ of Clerkenwell Green and its surroundings ends in a car park at the corner of Clerkenwell Road and Goswell Road. Standing amidst the cars parked in this vacant lot of prime London building land, there are two enormous works of graffiti to be seen. One work depicting a female figure is by Italian artist Vera Bugatti (born 1979; see: http://www.verabugatti.it). The other work depicts people walking at night in a wet street with unfurled umbrellas. It is painted by British born Dan Kitchener (born 1974), a prolific street artist (see: http://www.dankitchener.co.uk/). I wonder what will happen to these pictures when eventually someone decides to build upon the presently vacant space.

Goswell Road graffiti

Clerkenwell Green and around it is full of interesting places that illustrate aspects of the history of London ranging from the 12th century to the present. Initially home to major religious establishments, the area has witnessed momentous social changes, and from being one of the poorest parts of London it has become one of the more prosperous and more fashionable parts of the city.

View of Clerkenwell Green from St James Church

MONKS and NUNS, MARX and LENIN remains copyright of the author ADAMYAMEY, a member of the travel community Travellerspoint.

Post tags: lenin london islington marx clerkenwell

Comment on this entry | Tweet this | Your own free travel blog | More Travellerspoint blogs

April 19, 2017

OUT OF INDIA

Side by side in Southall

Ever since the 17th century, people from the Indian subcontinent have been arriving in London, and settling there. Some of the earliest arrivals were seamen, who had been recruited to work for the East India Company. Others were servants of Europeans, who had been brought 'home to England' by their employers. Later on, scholars and wealthier people from India came to see, study, and maybe settle, in London. These included well-known figures such as Mahatma Gandhi, Mohamed Ali jinnah, and Jawarhalal, all of whom returned to their homeland eventually. When Idi Amin expelled the Asians from Uganda in the early 1970s, many of them settled in London and other parts of the UK. Whatever thier history, folk from India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, have established thriving communities in London and elsewhere. Parts of London could almost be India, but for the relatively dismal weather! This blog article presents pictures that I took a few years ago mainly in London's Southall, but also elsewhere in London

Mc Don-HALAL-ds. In southall

Jalebi junction. Southall

Spicy in Southall

Cooking a l'indienne, Southall

Nagina

Now only a memory, The Himalaya Cinema in Southall used to screen 'Bollywood' Movies

Himalaya Cinema: poster

Himalaya Cinema, Southall

Future leaders of modern India ate at this restaurant in the Strand, India Club Restaurant. It still exists, and looks much as it might have done in the late 1940s.(143 Strand, London WC2R 1JA)

A great Indian eatery in the Strand

Brick Lane today is the centre of a large Bangladeshi community. Neither the Moslem Bangladeshis nor their predecessors the Eastern European Jews would have approved of the food mentioned in this street sign:

Neither kosher nor halal

Thirsty? Why not have a 'pinta' at a Punjabi pub?

Punjabi pinta... Southall

In need of spiritual guidance?

Four tongues, one faith. Southall

Jain Temple, Southall

Rhapsody in blue

Shopping

Four ladies in a window, Southall

In Southall

DVD seller in Southall

Neck-lace shop in Southall

Chappals in Southall

Purely Cosmetic. Southall

The British in India

Brave companions in India

I hope that you have enjoyed these few glimpses of the colourful world that immigrants from the Indian subcontinent have introduced to brighten our life in London

Rolling a roti in Southall

OUT OF INDIA remains copyright of the author ADAMYAMEY, a member of the travel community Travellerspoint.

Post tags: london india indians pakistanis bangladeshis

Comment on this entry | Tweet this | Your own free travel blog | More Travellerspoint blogs

April 11, 2017

POLITICIANS, PROSTITUTES, and PRIVATE CLUBS

Park Lane Hilton Hotel overlooks Curzon Street

I have been visiting Curzon Street in London’s Mayfair for many decades, usually to watch a film at the Curzon Cinema. For a long time, this was one of the most comfortable cinemas in London, but now, at last, many other cinemas are providing seating at least as comfortable as that in the Curzon. Many years ago, I visited Shepherd’s Market, which is close to the Curzon Cinema, to eat at Tiddy Dol’s Restaurant. The restaurant no longer exists, but the cinema is thriving. This essay explores some of the sights on Curzon Street, an interesting thoroughfare, which is, unusually, devoid of food shops (e.g. grocery shops, butchers, etc.)

Curzon Street runs from Park Lane eastwards towards Fitzmaurice Place, which runs south from nearby Berkely Square of singing nightingale fame. It is not named, as I have always believed, after Lord Curzon (1859-1925), a former Viceroy of India. The street existed long before the Viceroy’s birth. The street has not always been known by its present name. It began life as ‘Mayfair Row’. It was named ‘Curzon’ after its one-time landlord George Augustus Curzon, third Viscount Howe.

1862 map showing Curzon Street

An 1862 map shows that Curzon Street then ran from ‘Seamore Place’, which is the site of the present Curzon Square (see below) to Half Moon Street, and then to the east of that, the street was then named ‘Bolton Row’. Bolton Row ran between Half Moon Street and where Fitzmaurice Place now runs. In 1862, the latter street did not exist, but where it is now, was part of the grounds of Lansdowne House.

A map published in 1750 shows that the former ‘Mayfair Row’ was already named ‘Curzon Street’, and ran from Park Lane to Half Moon Street where it became ‘Bolton Row’. At that time, only the southern side of Curzon Street had a few buildings along it. The northern side was devoid of buildings except for the boundary wall of the grounds of Chesterfield House (see below). Sometime between 1750 and 1800, the section of Curzon Street between the present Curzon Square and Park Lane was built on. To enter the west part of Curzon Street from Park Lane, it became necessary to enter Pitts Head Mews, which is currently bordered by the Park Lane Hilton Hotel, and then to pass northwards through a narrow alley way to reach Seamore Place (now ‘Curzon Square’). The northern end of Seamore Place was the western end of Curzon Street. And, this is how the road layout remained until after about 1930.

Number 1 Seamore Place and its grounds that extended to Park Lane (and therefore closed off direct access from Curzon Street to Park Lane). It was the home of Alfred de Rothschild (1842-1918), the first Jewish person to be the Director of the Bank of England. Benjamin Disraeli, who became one of Rothschild’s neighbours, said of number 1 Seamore Place that it was:

“...the most charming house in London, the magnificence of its decorations and furniture equalled by their good taste”

And, he was well qualified to say that because in 1880, Rothschild had given him a suite of rooms in his house to use whenever he wanted (see: “Disraeli”, by R Blake, publ. 1966, and https://family.rothschildarchive.org/...)

The house was demolished between the two world wars to enable Curzon Street to be re-connected with Park Lane. In connection with this house, the Rothschild Archive website records:

“Alfred bequeathed both the house and its contents to Almina, Countess of Carnavon, whom he acknowledged as his illegitimate daughter. The proceeds of the sales she made helped finance the excavations carried out by Lord Carnavon and Howard Carter in Egypt at which Tutankhamen's tomb was discovered.”

Curzon Square stairs

We begin our exploration of Curzon Street in Pitts Head Mews at the base of the Hilton Hotel. A short, narrow staircase leads up (northwards) from opposite the Hilton’s tea rooms into Curzon Square. The west side of Curzon Square (formerly ‘Seamore Place’, and then ‘Curzon Place’) consists of buildings that look more recent than what must have been there in the early 19th century. In addition to the Rothschild’s house, the west side of the former Seamore Place was occupied by homes belonging to people, whom the novelist Georgette Heyer would have described as being of ‘bon ton’. These houses had gardens extending to Park Lane.

Curzon Sq with stone benches

Curzon Square: sunken garden

Today, the square, which contains some slender young trees, is provided with attractive marble benches for public use. The eastern side of the square has buildings that are older than those on the western side. At least, they appear to be older. The building on the western corner of Curzon Square and Curzon Street has a fine sunken garden behind it. This is viewable from the square. The building was originally Georgian, but after suffering bomb damage in WW2, it was clumsily restored. It was in a flat inside this building that Keith Moon of “The Who” pop group died in 1978. Some years earlier, in 1974, another pop musician Mama Cass Elliot also died in the same building.

Curzon Street: number 19 Disraeli lived here

Entering Curzon Street, we find two long established clubs on its south side. One is Aspinall’s and further along there is Crockfords. Between them and Curzon Square is the former home of a Victorian Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881). He lived in number 19, which was built in about 1758, during the last year of his life. He bought the house using proceeds from the sales of his novel “Endymion”. He only lived long enough to be able to host one dinner party there, the last he was to hold before he died. Amongst the guests at this occasion was his neighbour and former host, Alfred de Rothschild, and also Lady Anne Chesterfield, with whom Disraeli had conducted a long and intimate correspondence (see: book by Blake).

CURZON STREET: lantern snuffers

Several of the houses in the row of buildings that includes number 19 have ironwork structures beside their front steps. Most of these have inverted metal cones attached to them. These cones were used to snuff out flaming torches that were used at night for illumination.

CURZON STREET: Rufus Isaacs house

Further along the street, there is a plaque on number 32. This commemorates Rufus Isaacs (1860-1935), the Jewish lawyer and statesman who lived and died in this building. Between his home and that of Disraeli, there are two clubs: Aspinalls and Crockfords. Aspinalls, now ‘Crown Aspinalls’ is an elite gambling club founded in the 1960s by John Aspinall. It moved to its present premises in Curzon Street in 1992. There is a metal model of an elephant on the doormat of the entrance to Aspinalls’s. Rather inelegantly one of its legs is attached to the railings with a bicycle clamp. This elephant may have something to do with the fact that the club’s founder John Aspinall (1926-2000), who was born in British India, was the owner of several zoos in the UK.

CURZON STREET: Elephant at Aspinalls

CURZON STREET: Crockfords

Almost its neighbour, Crockfords, another gambling club, has a longer history than Aspinalls. It was established by William Crockford (1776-1844), the son of a fishmonger, as a ‘private members’ gaming club’ in 1828. It is said that even the Duke of Wellington joined this club, if only to be able to blackball his son, Lord Douro, to prevent him from becoming a member. Crockfords was originally housed in St James Street, but moved to its present location much later. This was after Crockford had bought a share in Watier’s gaming club that was in what used to be Bolton Row (now Curzon Street). Watier’s failed, but Crockford was able to continue in the gaming business, and died a very wealthy man.

CURZON STREET Egyptian Embassy at corner of Chesterfield Gardens

Across the road from Crockfords, there stands a building owned by the Egyptian Government, a 19th century building on the corner of Curzon Street and Chesterfield Gardens. This building was bought from a Jewish banker shortly after the Egyptians had acquired Bute House (in South Audley Street, now the Egyptian Embassy) in 1925. This became the ‘Royal Egyptian Club’ for a while, and is now still used by the Egyptian government (see: http://www.egy.com/landmarks/95-02-04...). In 2013, objects from University College’s Petrie Egyptological museum were temporarily displayed in this building (see: http://www.ai-journal.com/articles/10...).

Wall at the end of Chesterfield Gdns

Chesterfield gardens is a cul-de-sac. It ends abruptly at an attractive, elegant brick wall decorated with bricked in arches and topped by a balustrade. Halfway along it, the wall increases in height and accommodates a second row of arches separated by Corinthian pilasters and surmounted by a triangular pediment. Maps drawn as late as 1862 show that Chesterfield Gardens did not yet exist, but its parallel neighbour to the east of it, Chesterfield Street, where both Beau Brummell (1778-1840) and Prime Minister Anthony Eden (1897-1977) once lived, did exist. The latter separated the grounds of Chesterfield House to its west from those of Wharncliff House (now ‘Crewe House’) to its east. Where Chesterfield Gardens runs today was, in the past, part of the grounds of Chesterfield House (built for Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield between 1747-1752), which occupied the (eastern) corner plot where South Audley Street meets Curzon Street. The house’s grounds were reduced in extent in 1869, when it was purchased by Mr Charles Magniac who created the street now known as Chesterfield Gardens. The elegant wall, which is now a protected structure, is believed to be a part of the northern wall of the former gardens of Chesterfield House (see: http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/a...). The house was demolished in 1937. Incidentally, the 4th Earl of Chesterfield’s daughter-in-law was Lady Anne Chesterfield, who had attended the only dinner party that Disraeli held in his Curzon Street home (see above).

CURZON STREET: Saudi Embassy in Crewe House

Whereas Chesterfield House no longer exists, its former neighbour to the east of Chesterfield Street still stands. Known as ‘Wharncliffe House’ prior to 1899 (when it was acquired by the Marquis of Crewe), Crewe House as it is now known, it is currently the home of the Saudi Arabian Embassy. Crewe House was built in 1730, but its interior has been much modified since then. Set well back from the street behind a large garden, this building is a now rare example of a central London mansion set in its own grounds. In 1918, during WW1, Crewe House became the headquarters of Lord Northcliffe’s department for producing and then distributing propaganda to attempt to change the minds of those fighting for Germany and its allies (see: “Secrets of Crewe House” by C Stuart, publ. 1920).

Curzon (Mayfair) Cinema

The Curzon Cinema (now ‘Curzon Mayfair’) is almost opposite Crewe House on the corner of Curzon Street and Hertford Street. This cinema, which is close to Shepherds Market (see below) is a masterpiece of 1960s architectural design, especially its largest auditorium. It was built beneath offices between 1963 and 1966 to the design of Sir John Burnet, Tait and Partners, architects in collaboration with H G Hammond.

Curzon Cinema: foyer detail

The luxurious foyer is divided into two parts by a sculptured wall screen. Tickets are sold at the long bar, which also serves drinks and snacks. Attractive abstract sculptural murals of fibre glass by William Mitchell and Associates line the side walls of the main auditorium. Its ceiling is a network of almost square recessed cells, each containing a light fitting. The seats in the auditorium are gently raked and very comfortable. The rake is slight but sufficient to ensure a good unobstructed view from each row.

Curzon cinema: auditorium mural

The Curzon Mayfair is the original member of the Curzon group of cinemas, and probably the most elegant of the group. Given its expensive Mayfair location, ticket prices are no higher than average. The reason that I first became attracted to this cinema was that during my student days (in the 1970s) it did not show as many ‘run-of-the mill’ mainstream films as most other cinemas. Like the now non-existent Academy cinemas in Oxford Street, it showed what some people refer to as ‘art films’. Nowadays, the Curzon and its branches tend to show mostly mainstream cinematic releases. Nevertheless, the Mayfair Curzon is a lovely place to enjoy watching them.

Shepherds Market

Hertford Street leads into the complex of small streets known as ‘Shepherds Market’. The market’s name has nothing to do with sheep; it commemorates Edward Shepherd, who developed the ‘piazza’ named after him during the period 1735 to 1746. It was built on fields where once a traditional May Fair used to be held. A network of cute narrow lanes surrounds the elongated piazza, which one might easily mistake for a stretch of wide street. This area is full of upmarket prostitutes, cafés, pubs, and restaurants, many of the latter providing middle-eastern fare.

Shepherds Market

One restaurant, which closed in 1998, was a landmark in Shepherds Market. This was ‘Tiddy Dol’s’, which was named after a famous Georgian street-seller of gingerbread snacks (see: http://scrumpdillyicious.blogspot.co....). I remember entering this rather gloomy eatery with my Italian brother-in-law, who wanted to try ‘real’ English food. We ordered him Welsh Rarebit, for which the restaurant was justifiably renowned. He looked at the dish in front of him, prodded its cheesy topping, and then made an involuntary expression that conveyed ‘disgust’ to me. Tiddy Dols was in the ‘epicentre’ of the prostitution ‘business’. So much so that:

“…in the late Seventies, commissionaires in the grand hotels of Park Lane would tell families of tourists not to go to Tiddy Dolls, such was the gauntlet of girls they would have to run.” (see: “The Independent” newspaper, 14th March 1996.)

Shepherds Market

Regardless of what you want out of life, Shepherds Market is a very pleasant and surprising enclave in the heart of Mayfair.

Shepherds Market: Kings Arms pub

An alleyway lined with eateries leads north from Shepherds Market past Da Corradi’s Italian long established (so long that it still displays its outdated 0171 telephone prefix code) restaurant to Curzon Street. To the left (west) of the alleyway on Curzon Street, you will find Maggs Bros. Ltd.

Shepherds Market entrance and Maggs Bookshop

This bookshop, which was founded in 1853, specialises in rare books and manuscripts. For 80 years until 2015, it used to have its premises at number 50 Berkeley Square. The business was started by Uriah Maggs (1828-1913), and remains under the ownership of his family. Apparently, one of Maggs’s more unusual dealings was the handling of a sale (for £400 in 1924) of a collection of mummified parts of Napoleon Bonaparte’s corpse including his penis (see, for example: “Lucy’s Bones, Sacred Stones, & Einstein's Brain: The Remarkable Stories Behind the Great Objects and Artifacts of History, From Antiquity to the Modern Era” by H Rachlin, publ. 2013)

Curzon Street: Heywood Hill

Almost opposite Maggs’s new premises on Curzon Street, there is another bookshop, Heywood Hill. The shop was opened by Heywood Hill in 1936, and has strong associations with Nancy Mitford (1904-1973), who was one of the famous ‘Mitford Sisters’. During WW2, Nancy, an accomplished author, worked at Heywood Hill, which, by then, had become:

“… a meeting place for London literary society and her friends.” (See: http://www.nancymitford.com/nancy/).

This bookshop, which helps the discerning reader (with ample income) to assemble collections of books for his or her library, is patronised by the Royal Family. It bears a ‘By Royal Appointment’ sign.

Curzon Street: Trumpers

Neighbouring Heywood Hill, there is a shop, Trumpers, which has nothing to do with the USA’s current president. The shop houses the premises of George F Trumper, “Court Hairdresser and Perfumer”. Founded in the 19th century by George Trumper, this is an up-market barber’s shop. Given the heritage and exclusivity of this establishment, its prices, although not cheap, are not unreasonable (see: https://www.trumpers.com/services_pri...). I have not made use of its services, but when I do go in there for a trim, I will join a host of well-known men, including King George V, Winston Churchill, John F Kennedy, Cary Grant and Michael Caine, who have all been groomed there (see: https://www.man.london/grooming/class...).

Curzon Street: Church of Christ Scientist: facade

On the same side of Curzon Street but east of Trumpers and Heywood Hill, there is the magnificent façade of the Third Church of Christ Scientist. And, it is truly a façade nowadays because it covers up the recent construction behind it. The building, of which only the façade remains, was designed by the architects Lanchester & Rickards, commenced in 1908, and opened for use in 1911. The original building had sufficient space to seat 1000 people.

Curzon Street Church of Christ Scientist: detail

The architectural writer Nikolaus Pevsner (1902-1983) remarked that the façade resembled that of a highly successful insurance company. In 1984, the Church decided to make a smaller place of worship on this site, and to develop the rest of it for use as commercial property and flats. These are tastefully arranged around a landscaped central courtyard.

Half Moon Street

The Church of Christ Scientist faces the beginning of Half Moon Street, which leads from Curzon Street to Piccadilly. The building of this street began in 1730. It was home to notable figures such as Dr Johnson’s biographer James Boswell, King Ludwig the First of Bavaria’s mistress Lola Montez, and Sax Rohmer, the creator of Dr Fu Manchu. This elegant street was also the location of Algernon Moncrieff’s ‘pad’ in Oscar Wilde’s play “The Importance of Being Ernest”. In fact, one scene is set in the: “Morning-room in Algernon’s flat in Half-Moon Street”.

Clarges Mews

Clarges Mews: western end

Before reaching the eastern end of Curzon Street, let us take a detour by entering Clarges Mews. This place is at the northern end of Clarges Street which crosses Curzon Street just east of the Church of Christ Scientist. Clarges Mews used to be called ‘Lambeth Mews’, so I discovered on an 1862 map. It still bore its earlier name on the 1891 Census. The mews runs parallel to Curzon Street and has a narrow pedestrian passage at its western end joining it to Queen Street. In “Lockies Topography of London…” published in 1810 (see: https://archive.org/stream/lockiestop...), it is stated that the mews also connected with Charles Street (this can be seen on Cross’s “New Plan of London” dated 1850), but now it does not do so.

Clarges Mews: house with a crest

This pleasant mews has one building, number 37, that captured my curiosity. It is a redbrick building with mansard windows and some white stone facings. It looks as though it might have been transported from a chic suburb of Paris. In between two of the first-floor windows there is a crest which looks like an interlinked ‘V’ and ‘R’. Above it, is the date 1890.

Clarges Mews: 1890 crest

An aerial photograph revealed to me that this building is at the rear of the courtyard of a building on Charles Street (numbers 37 and 38), Dartmouth House, which is now the English Speaking Union and is built in the same ‘French rococo’ style. Originally built in the Georgian style in the middle of the 18th century, it was modified to imitate the French style in 1870 by the banker Edward Baring (1828-1897).

In 2009, Clarges Mews hit the headlines when a group of squatters was eventually evicted from properties on Clarges Mews (see: “The Guardian” 28th January 2009). The squatters were a group of young artists that were sometimes known as the ‘Da! Collective’. According to “The Guardian” they were:

“…squatting under the banner of the Temporary School of Thought at their latest address, where they held weeks of workshops and activities. They invited members of the public into the sumptuous property to learn new skills – there were free classes on everything from Hungarian folk singing to treehouse building and how to dance the Charleston.”

At the same time as the squatters in Clarges Mews were evicted, so were others in properties along nearby Park Lane.

Landsdowne Club

The eastern end of Curzon Street, where it meets Fitzmaurice Place, is occupied by the Lansdowne Club. This private club was established in 1935 in Lansdowne House. The construction this house to the designs of Robert Adam (1728-1792) was slow, lasting from the early 1760s to the early 1780s. Looking at the outside of the building (once a private mansion with grounds extending to Berkely Square), you would never imagine that this was originally a Robert Adam building. This is because in 1933:

“Lansdowne House is radically restructured. Adam’s façade is cut back forty feet. The First Drawing Room and Great Eating Room are dismantled and shipped to America” (see: https://www.lansdowneclub.com/about-t...).

Two years later, the Bruton Club, which was housed in this building, was re-named the Lansdowne Club. In 1964, the building was further curtailed when Westminster Council demolished Lansdowne Steps to allow the extension of Curzon Street eastwards to join Fitzmaurice Place, which became a public thoroughfare in 1935.

Landsowne Club: entrance

Before becoming a club, Lansdowne House had been a private residence. Its owners had been the Marquesses of Lansdowne, members of the Shelburne family that included some Fitzmaurice ancestors. The Fifth Marquess of Lansdowne rented the house to Gordon Selfridge (1858-1947), the American owner of London’s Selfridge department store. In 1929, the Sixth Marquess of Lansdowne sold the family home to an American property developer, who, in turn, sold it to the Bruton Club.

Landsdowne Club: interior

I have been lucky enough to have been invited to dinner by a member of the Lansdowne Club. Many of its common areas, corridors, entrance hall, and dining room, are decorated in the art-deco style, and very well-maintained. Incidentally, the food in the dining room was excellent. On that cheerful note, we reach the end of my amble along Curzon Street, a thoroughfare that certainly does not lack in interest.

CURZON STREET detail on a facade opposite the Saudi Embassy

POLITICIANS, PROSTITUTES, and PRIVATE CLUBS remains copyright of the author ADAMYAMEY, a member of the travel community Travellerspoint.

Post tags: london mayfair curzon street

Comment on this entry | Tweet this | Your own free travel blog | More Travellerspoint blogs

April 5, 2017

POP GOES THE WEASEL: Wesley, Bunyan, Blake, and Crapper

The City Road runs south-east from The Angel at Islington to Old Street roundabout, and then more or less south to Finsbury Square.

Leysian Mission building

My interest in this busy road began when I noticed a Victorian building with an elaborate red stone façade, which reminded me of a similar edifice in Russell Square, the Russell Hotel. The building on City Road is just north of the Old Street Roundabout, and bears the words ‘Leysian Mission’ above its main entrance.

The City Road forms part of an inner ‘ring road’. It was built in 1761 to connect the City to Pentonville Road, effectively a road that bypassed the busy centre of London. A 1781 map in the British Library shows that the part of City Road, north of what is now the Roundabout, ran through open countryside until it reached Old Street. The part of the modern City Road that heads southwards from Old Street was more built-up, and was then called ‘Royal Row’. Several things marked near Royal Row on the 1781 map are relevant to what I will describe later. To the west of the Row, there is a large open space marked on this map as ‘Artillery Ground’, and immediately north of it there is a ‘Burial Ground’. A short distance to the west of the Burial Ground, there is a small rectangle marked as ‘Quakers Gr.” Opposite the Burial Ground, but east of it across Royal Row, there was an empty triangular plot, and immediately east of that there was a largish plot labelled ‘Foundery’.

1781 map of Royal Row, which is now the part City Road south of Old Street

I will now guide the reader northwards from what used to be the Artillery Ground to the Leysian Mission and then further north along City Road.

Finsbury Barracks

Today, a mock Tudor castle stands on the northeast corner of Artillery Ground with its façade on City Road. This incongruous structure is Finsbury Barracks. It was completed in 1857 to the designs of the architect Joseph Jennings. It was built for Honourable Artillery Company, incorporated by King Henry VIII in 1537, and is thus one of the world’s oldest military organizations. It is only a few decades ‘younger’ than the Pope’s Swiss Guards, and is the oldest regiment in the British Army. Apart from military duties, the Company provides the Honourable Artillery Company Detachment of Special Constabulary, which is a police force attached to the City of London Police. The Special Constabulary assists in maintaining law and order in the City of London (as opposed to Greater London).

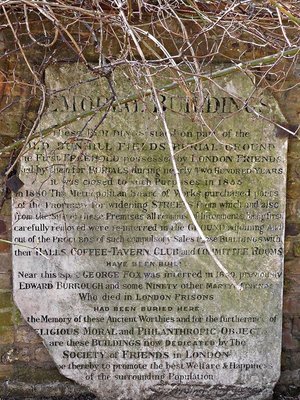

BUNHILL FIELDS with Finsbury Barracks

The burial ground to the immediate north of the Finsbury Barracks is now known as ‘Bunhill Fields’, but in the mid-18th century it was also known as ‘Tindal’s Burying Ground’. The name Bunhill is said to derive from ‘Bone Hill’, which the area was given since it was used for burials as early as during the Saxon period. Another likely explanation of the name Bone Hill is that when the St Paul’s charnel house was demolished in 1549, many thousands of bones from it were dumped in the Bunhill district. These bones were piled up and covered to produce a raised portion of land – a hill! During the Great Plague of 1665, corpses were buried in this area, but it was never consecrated by the Church of England. When Mr Tindal took over the lease for what is now Bunhill Fields in the 17th century, he permitted burials of non-conformists, that is Protestants who practised their religion outside of the Church of England. Anyone, who could afford Mr Tindal’s fees, could be buried in his graveyard. Non-conformists continued to be buried at Bunhill Fields until 1854, when it was deemed to have been completely filled up.

BUNHILL FIELDS

Today, Bunhill Fields is open to the public. Most of the graves are enclosed in grassy areas planted with flowers and surrounded by railings. Wide paved footpaths pass between the enclosures, and are much used by city workers hurrying from A to B. The place is very picturesque with many trees and a rich variety of weather-beaten gravestones, many of whom bear inscriptions that are becoming hard to read. Here and there, benches are available for the weary, and to the north of the gravestones there is a large grassy area. This venerable cemetery is overlooked in one corner by the castle-like Finsbury Barracks, and in many other directions the skyline is dominated by construction cranes and new buildings. The exception is to the east, where all that you can see between the passing traffic on the busy City road is a complex of old buildings that I will describe soon.

BUNHILL FIELDS: John Bunyan

BUNHILL FIELDS John Bunyan

Bunhill Fields is the final resting place of many well-known people as well as those whom time has forgotten. Amongst the ‘celebrities’ interred at Bunhill is the author of “Pilgrims Progress” John Bunyan (1628-1688). His monument is not enclosed, and is close to that of another author, Daniel Defoe (1660-1731), whose monument is also not behind railings.

BUNHILL FIELDS Daniel Defoe monument

Close to both of these authors, and also unenclosed, is a stone commemoration the poet and artist William Blake (1757-1827).

BUNHILL FIELDS William Blake

These three graves are easy to spot whereas those of, for example, Thomas Bayes (mathematician and clergyman) and Susanna Wesley (mother of Charles and John Wesley) are difficult to spot even though a map in the cemetery gives approximate locations for them.

BUNHILL FIELDS Detail of gravestone of John Wheatly died 1823

Close to Blake’s memorial, but behind railings, there is a black gravestone commemorating John Wheatly who died in 1823, aged 84 years. This well-preserved gravestone has a circular bas-relief showing allegorical representations of the transience of life. According to one source (https://historicengland.org.uk/listin...

“The monument is an upright slate slab with a shaped top. At the top is an inset roundel containing various funereal emblems carved in relief: a naked human figure bearing a scroll marked ‘Ashes to Ashes’ contemplates a flaming urn marked ‘Dust to Dust’ and a skull marked ‘Mortality’. He stands atop a globe bearing a text from Shakespeare's Tempest: ‘The great Globe itself - shall dissolve, &c. &c.’ On the left is a snuffed-out candle, and at the base a crucifix and an anchor, representing faith and hope respectively.”

The visitor should look out for this fine work of funerary art.

BUNHILL FIELDS Mary Page

BUNHILL FIELDS Mary Page

It is hard to miss the huge unenclosed memorial to Dame Mary Page, wife of Sir Gregory Page. She died aged 56 in 1728, so one side of the memorials proclaims. The other side of the memorial has the following written on it:

“In 67 months she was tap’d 66 times. Had taken away 240 gallons of water without ever repining her case or ever fearing the operation”.

According to one source (http://londonist.com/london/history/l...), Lady Page, a well-respected philanthropist) suffered from a form of ‘dropsy’ (or soft tissue oedema), which caused accumulation of fluid to build up in the space around her lungs. The above-mentioned source suggests that the 29 pints (13 litres) of water ‘tap’d’ on each occasion seems to be rather an exaggerated amount. Whatever the actual amount, it cannot have been pleasant for the poor lady. Recently, I suffered from a pathological accumulation of only 1 litre of superfluous fluid, and that was bad enough!

BUNHILL FIELDS: gravestone with a skull

Lady Page lies in the western half of the cemetery. Further west, about one block away from Bunhill Fields, there is what remains of another graveyard, that used by the Quakers. The Quakers - a sect of Christian ‘dissenters’ - were founded as the ‘Society of Friends’ by George Fox (1624-1691), who travelled around Britain preaching. Being ‘non-conformists’, the Quakers could not be buried in the usual graveyards where conforming Protestants were interred. In 1661, the Quakers bought a plot of land to use as a burial ground. This was four years before the establishment of the burial ground for non-conformists at nearby Bunhill Fields.

QUAKER GARDENS general view

QUAKER FIELD old memorial sign

Quakers Garden contains what little remains of the Quakers’ first cemetery. An 1871 Ordnance Survey map marked it as being ‘disused’. It is now a park equipped with a fine children's playground. A monument, recently placed, commemorates the Garden’s original purpose. And, near to the western edge of the plot, there is an old carved stone with some historical information about the Quakers’ use of the area. Near that, there is a marker which has been placed close to where George Fox was buried. These monuments are in the shadow of a small disused building that used to be the caretaker’s house for a larger complex of Quaker buildings, the Bunhill Memorial Buildings, which contained rooms for committee meetings, refreshments, etc. It is now used as a Quakers’ meeting house. The peaceful Quakers Garden is a pleasant place to sit and relax.

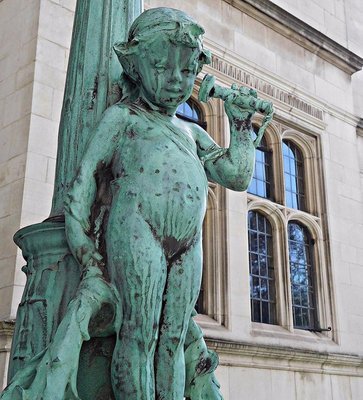

JOHN WESLEY statue and Wesleyan Chapel

Looking across the City Road from the eastern gates of Bunhill Fields, one sees a rectangular open space surrounded on three sides by old buildings. A statue of John Wesley (1703-1791) with his right hand outstretched welcomes the visitor to the paved yard behind him. He stands in front of an elegant chapel and between his former home to his left, and some administrative buildings labelled ‘Leysian Mission’ to his right. The courtyard and the buildings surrounding it form what might best be described as a ‘Wesleyan enclave’.

The Wesleyan Chapel

I entered a door to the left of the front of the chapel, and immediately noticed the smell of burning. A man of oriental appearance wearing a smart suit welcomed me, and told me that if I had come to see the museum, that would not be possible because there had been a fire the day before in the chapel’s crypt, where the museum is located. He led me across the courtyard to the rear entrance of Wesley’s house, where he introduced me to a lady who was willing to show me around the chapel.

Wesleyan Chapel: pillar in red stone

My guide took me inside the chapel, apologising that the electric supply to it had been disrupted by the fire. It was light enough to see the chapel in all its glory. The chapel is rectangular with a horseshoe shaped gallery that is supported by beautiful mottled pinkish-red pillars made from Italian stone. An article on the Chapel’s website (http://www.wesleyschapel.org.uk/histo...) says of these pillars:

“In 1891 the Chapel was transformed to commemorate the centenary of Wesley’s death. Marble pillars were donated from Methodist Churches around the world to replace the original pillars made from wooden ships’ masts donated by George III. New pews were also added and the stained glass was installed around this period.”

Wesleyan Chapel ceiling

The finely decorated ceiling rests on the four walls of the chapel without any transverse supports, making it one of the largest ‘unsupported’ ceilings of the era, the late 18th century. Designed by George Dance the Younger in the Georgian style, it was opened in 1778. There is a lot that could be written about this chapel, but I will only mention some of the things that attracted me.

Wesleyan Chapel: slide out seat for extra seating

The oak pews that are newer than the chapel itself have a curious feature. Each row of pews has at its end a drawer-like mechanism that slides out to produce a folding seat which can be used to provide extra seating. A stucco frieze runs around the base of the gallery. This consists of many identical circular designs (roundels) that, at first glance, appear to depict a dove swooping downwards with something in its beak. Closer examination reveals that the circles surrounding the doves are depictions of snakes with their tails in their mouths. The symbolism of these roundels that were designed by John Wesley relates to contrasting war and peace. Light floods into the chapel through large windows spaced at regular intervals around the walls of the gallery.

Wesleyan Chapel Wesley: roundel with dove and snake design

The simple wooden communion rail surrounding the high altar is relatively modern. It was donated by former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who was married in this chapel in 1951. I believe that her children were baptised there as well. Enclosed by this rail and immediately behind the Cross, stands a centrally placed wooden pulpit with a short helical staircase. A carved marble (or alabaster) font stands close to the main altar. Inside the basin of the font there is a square grey coloured carved stone. This came from the West Indies, and relates to the Wesleyans’ (i.e. Methodists’) interest in the abolition of slavery.

Wesleyan Chapel: font with 'slavery' stone from West Indies

A door near the font leads from the chapel to the ‘Foundery Room’. Its name is a commemoration of the first Wesleyan chapel that was built in this area in the grounds of a former foundry close to where the present chapel now stands.

Pew from original Foundery chapel now demolished

Wesleys organ

The Foundery, an ordnance workshop, was opened in 1684, but was closed following an explosion in 1716. In 1739, John Wesley acquired the site and built his first London chapel there. It was used until the present chapel was built. Wesley’s mother, who is buried in Bunhill Fields, died in the old chapel in 1742. The present ‘Foundery Room’ contains not only John Wesley’s own organ but also some of the wooden pews that were once used in the original chapel on the foundry site.

John Wesleys grave and the Wesleyan Chapel

It is worth entering the peaceful small garden/graveyard behind the chapel. Here you can see another monument to John Wesley. This one stands above his grave, upon which there is a short carved elegantly worded eulogy. I was told that at lunchtime many local workers sit in this garden eating their sandwiches.

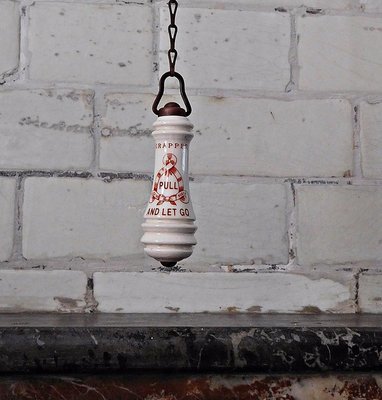

Thomas Crapper: pull and let go

Wesleyan Chapel: Victorian gents toilets

My guide was very keen that I should visit the toilets attached to the main chapel. And, I could see why. The ‘gents’ toilet is one of London’s very few perfectly preserved, still functioning, Victorian lavatories. The urinals, the washbasins, the toilet cubicles, and the china fittings, are all original. Many of the china fittings including the flush chains and the toilet bowls bear the trademark of Thomas Crapper & Company (founded 1861 see: http://www.thomas-crapper.com/The-His...). After using the facilities, I spent some time photographing them. When I returned to my guide, she hoped that I had not been unwell as I had taken so much time in the toilets. I assured her that it was fascination rather than illness that had delayed me.

Wesleys house

After seeing the chapel, I was taken back to John Wesley’s former home, and put in the care of another lady, who guided me expertly around it. Before continuing, I will try to summarise, as briefly as possible – and over-simplistically (because I am no expert on comparative religion), why John Wesley has become so well-known. He founded Wesleyan Methodism. In his “Dictionary” of 1755, Samuel Johnson defined a Methodist as:

“… one of a new kind of puritan lately arisen, so called from their profession to live by rules and in constant method”

A great preacher and leader of men, John Wesley attracted large numbers of people to his ways of worshipping God, and while so doing promoted the interests of those less privileged members of society. A great missionary and evangelical movement, Methodism attracted followers from all social classes, but especially brought its message to criminals and the labouring classes, and, also, to the black slaves, who later adopted its practises for use in their own churches. An article published by the BBC (http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religio...) summarises the beliefs of Methodists as follows:

“Methodists stand within the Protestant tradition of the worldwide Christian Church. Their core beliefs reflect orthodox Christianity. Methodist teaching is sometimes summed up in four particular ideas known as the four ‘alls’:

All need to be saved - the doctrine of original sin. All can be saved - Universal Salvation. All can know they are saved – Assurance. All can be saved completely - Christian perfection.”

The above seems to suggest that the Methodists are prepared to embrace everyone regardless of their imperfections and beliefs. The Methodists are non-conformists because they do not conform to the rules and traditions of the Church of England.

John Wesley’s home, which fronts on City Road, is a tall, narrow, typical 18th century town house. Its construction was commissioned by Wesley, and he moved into it in October 1779. The house, which is filled with contemporary fittings and furniture – some of it Wesley’s own, provides a good idea of what a remarkable man he was in addition to being a significant religious leader. I will give you a few examples of what I mean.

J Wesley and his cupboards

In a room on the first floor, there is a fine portrait of John Wesley above a fireplace flanked by two glass-fronted cupboards. These cupboards, which look as if they could have been designed in the 20th century, were designed by Wesley himself. Another room contains Wesley’s ‘jockey’ chair (which can be used either sitting normally on it or by straddling one’s legs around the chair’s slender backrest) with an attached reading stand. This room also contained a hand-cranked machine for generating static electricity. The electricity generated with this was used in order to try to cure a variety of medical disorders. Wesley was interested in medical matters, and published at least one book, “Primitive Physick, or An Easy and Natural Method of Curing Most Diseases”. It was published first anonymously in 1747, and then under his own name in 1760.

Wesley's electrotherapy machine

Wesley was used to spending almost 9 months of the year on horseback, travelling from place to place preaching. To compensate for the relative lack of exercise during the remaining months when he was not on horseback, he used an early form of exercise machine. It was a seat on springs, which could be forced to move up and down with some effort as the user exerted his muscles to effect this. The Wesley House has been fortunate enough to have been donated a genuine example of the very same machine that Wesley used.

18th century exercise machine

Wesley’s bedroom is on the second floor. A small room that leads off it contains the small desk that used to hold Wesley’s Bible and prayer books. Every morning at 5 am when he was in London, Wesley woke, and then prayed at this desk for some time before commencing the rest of the day’s activities. The small room has its own fire place, and above it a cupboard that was used as an airing cupboard.

Wesley prayed here alone every 5 am

During the tour around his house, the guide told me much about John’s family. His brother Charles (1707-1788) was a Methodist and a noted musician and writer of at least 6,000 hymns, amongst which “Hark the Herald Angels Sing” is particularly well-known. Charles’s son Samuel (1766-1837) was a contemporary of Mozart and, like him, a child musical prodigy. A brilliant composer, Samuel’s moral conduct was definitely inferior to that of his father and uncle John. Eventually, to his family’s dismay, Samuel became a Roman Catholic.

I hope that I have managed to give something of the flavour of visiting Wesley’s Chapel and home, and that this will encourage you to pay a visit to this interesting Methodist enclave.

Former Finsbury Technical College

Leonard Street that runs east of City Road just north of the Wesleyan enclave contains an elegant building with an interesting triangular pediment above its main entrance. The pediment contains carvings of old-fashioned scientific equipment and also piles of books marked “Wheatstone, Rankine, Faraday, Newton, and Liebig”. I could find no identifying marks on the building, but on examination of a detailed map published in 1897 I noticed that there was a ‘technical college’ marked where this building now stands.

Finsbury Technical College on LEONARD STREET

This was the former Finsbury Technical College, which was opened in1893 and was the first college of its kind in the UK. Its purpose was to be a ‘model trade school for the instruction of artisans and other persons preparing for intermediate posts in industrial works’ (see: http://www.herberthistory.co.uk/cgi-b...).

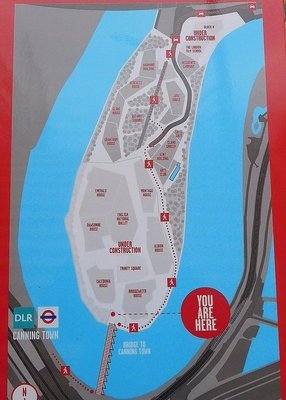

OLD STREET roundabout

North of this, City Road is interrupted by the Old Street Roundabout. In the middle of this there are two metal arcs (or semi-circles) that support 4 electronic advertising screens. Various entrances to Old Street Underground Station surround the roundabout. All of them lead to a huge subterranean shopping centre, which was built in the 1960s near the site of an ancient well, St Agnes’s Well. The shopping centre is named after this well.

Leysian Mission doorway

Having traversed the roundabout by a series of pedestrian crossings or by utilising the underground passageways, we arrive at the continuation of City Road, on whose west side stands the building that first aroused my interest in City Road, the former Leysian Mission building, now known as ‘Imperial Hall’.

The Leysian Mission was founded in 1886 by people who had attended the Leys School in Cambridge. This school, which catered for the sons of lay Methodists, was itself founded in 1875. The name derives from the fact that the school was built on the grounds of Leys Estate in Cambridge. The crest above the main entrance of the City Road building bears the Latin words ‘In Fide Fiducia’ (In Faith, Trust), which is the motto of the Leys School in Cambridge. The object of the Mission organization was to promote the welfare of the poorer people in the UK. In the era before the advent of the ‘welfare state’ it offered health services, legal assistance, sporting activities, and entertainment, to the deprived sectors of British society. To house these services, the Wesleyan Methodists set up about one hundred halls around the country. Imperial Hall on City Road was one of these.

CITY ROAD: Leysian crest

Between 1900 and 1904, the Imperial Hall was constructed according to plans drawn up by the architects Bradshaw and Gass of Bolton. Their firm Bradshaw, Gass, & Hope, which has designed many grand public buildings, was founded in 1862, and is still in business today. According to one source (https://www.imperialhall.co.uk/), the Imperial Hall contained the:

“…Great Queen Victoria Hall, which seated nearly 2,000 people, boasted a magnificent organ as well as a stunning stained glass windows by W. J. Pearce of Manchester, heavily influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement.”

In its heyday, the social centre was much-used. In 1907, about 5000 men, women, and, children made use of the Imperial Hall’s facilities every Sunday. There were over 1100 members of this branch of the Mission, and by 1912 the Mission had over 100 officers, who visited 3500 homes a week throughout the year. After the end of the First World War, this branch of the Mission helped many ex-servicemen who were returning home. During the Second World War, Imperial Hall was damaged by aerial bombing, but later restored.

By the late 1980s, the state funded welfare system was rendering the Leysian Mission’s objects redundant. The Mission building closed in 1989. Today, the interior of Imperial Hall no longer resembles its original form, but the glorious façade remains unchanged. The great hall has been removed, and the building contains sixty-three privately owned residential apartments, which vary in size from one to three bedrooms. These are not flats that would be affordable by the kind of people that the Mission was set up to assist.

Former Alexandra Trust

Another 19th century building close to this former Methodist inspired welfare centre bears the words “The Alexandra Trust Dining Rooms”. This philanthropic institution was built in 1898 by Sir Thomas Lipton (1848-1931), who had made his fortune in the tea business. This building contained a restaurant which:

“… offered very cheap meals to the poor working classes. Six boilers could heat 500 gallons of hot soup and a three-course meal cost 4.5d (2p) in 1898. Some 100 waitresses could serve up to 12,000 meals a day.” (Source: http://www.edwardianpromenade.com/)

The Alexandra provided some of the cheapest wholesome meals in the city. Today, the building houses the ‘Z Hotel Shoreditch’, a member of the Z Hotels chain.

CITY ROAD M by Montcalm

Across the road from it, there is a wedge-shaped skyscraper, a very much sharper and newer version of the Flatiron Building in Manhattan. The converging walls of this new building meet to form a razor-sharp edge where Provost Street meets City Road.

CITY ROAD M by Montcalm

This 18-storey building is called ‘M by Montcalm’ and was designed by the architectural practice of Squire and Partners. It opened in 2015.

Continuing north along City Road (on the same side as the former Alexandra Trust Dining Rooms), we reach the older part of Moorfields Eye Hospital. Founded in 1805 as an eye and ear hospital, it moved from its original site on the Moorfields (an open space upon which Finsbury Circus now stands) to its present one in 1899.

Moorfields Eye Hospital

There is an eye-shaped clock above the main entrance of the red brick building.

Moorfields Hospital extension

An ugly white tile-clad extension to the north of this building bears the name ‘King George V Extension’. This was opened in May 1935. The hospital is a world-famous centre of excellence.

Eagle Buildings

A few yards north-east of the eye hospital, there stands a 19th century building labelled ‘Eagle Dwellings’. It has shops at ground level and flats above it. Once, the music hall artiste Lily Morris (1882-1952) lived in one of the flats, in number 16 according to the 1891 Census (see: http://www.rootschat.com/forum/index....). Nowadays, Eagle Dwellings provides ‘supported accommodation’ under the auspices of a housing trust.

Victoria Miro Gallery