Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 231

March 15, 2017

WALKING IN AND AROUND WAPPING

An alley leading to the River Thames at Wapping

I thought that I knew all about Wapping until I met Fergy. He spent a sunny day with me showing me many historical places that I had not known about. When he offered to show me around that area, I was worried that he would insist on going to the one pub in Wapping that I have visited, the very crowded and tourist ‘infested’ ‘Prospect of Whitby close to Shadwell Basin. I need not have been concerned.

Wapping is now part of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It stretches along the northern shore (left bank) of the Thames east of the Tower of London, and inland to the Highway (the A 1203). The name Wapping derives from the group Saxon people, the ‘Waeppa’, who lived in the area. Until recent decades, Wapping, being so near the Thames, was intimately involved in all aspects of maritime life – both good and bad!

We began our walk at the Tower of London. After passing through the now very ‘glitzy’ redeveloped St Katharine Dock, filled with luxury yachts and cruisers, we began walking along the long winding Wapping High Street that follows the shoreline of the Thames.

Hermitage Riverside Memorial Garden

We came across a grassy open space. This green riverside park, the Hermitage Riverside Memorial Garden, is surrounded by blandly designed, unexciting modern apartment blocks. They stand where many decades ago the homes and workplaces of many east Londoners once stood.

Blitz Memorial

Between September 1940 and May 1941, London was heavily bombed by German warplanes. The so-called ‘Blitzkrieg’ was designed to demoralise the population of London, but failed to do so. However, it left much destruction of buildings and many human casualties. A monument in the gardens commemorates the civilians killed during the Blitz. The monument is a rectangular metal slab in which a dove-shaped window has been cut. It was designed by Wendy Taylor.

Blitz Memorial: plaque

The park and its waterfront provide an excellent place from which to view both Tower Bridge and the new 'Shard' skyscraper.

Town of Ramsgate pub

Our next stop on that warm sunny day, the ‘Town of Ramsgate’ pub, was for refreshment.

Town of Ramsgate pub

Long and narrow, stretching from the street to the waterside of the River Thames, this pub has an association with the notorious ‘Hanging Judge’, Judge Jeffreys. Just after King James II fled from Britain (in 1688) and when William of Orange (William III) was approaching London, Jeffreys tried to flee in order to follow the King abroad.

Town of Ramsgate: Judge Jeffries plaque

Having entered the ‘Town of Ramsgate’ in disguise, he was recognised by someone whom he had condemned, but had been later reprieved. A mob tried to lynch Jeffreys, but instead were persuaded to deliver him into the ‘protection’ of the Lord Mayor of London, who secured him in the Tower of London where he died of kidney disease. A small plaque in the pub records this story briefly.

Unlike its busy neighbour the ‘Prospect of Whitby’, this is still a ‘genuine’ local pub, not a ‘tourist trap’. It offers a good range of drinks as well as good food. The chicken curry that I ordered was not only tasty, but also it had been made from scratch in the pub’s kitchen rather than been brought in from an outside source and rewarmed.

Sadly, the small waterfront garden was cluttered with scaffolding connected with building works that were being carried out on its much larger neighbouring building, a converted warehouse (formerly ‘Oliver’s Wharf’). Once this building material disappears, this charming little garden will be a nice place to sit in decent weather.

St Johns Churchyard Wapping

Opposite the pub, there is a grassy open space with trees and a few old gravestones around the edges. This was the graveyard of St John’s Church, which stands on Scandrett Street that runs along the eastern edge of the graveyard. St Johns was built in 1756, but it was badly damaged by bombing in 1940 and most of the church had to be demolished. Today, the lovely tower of the church can be seen, and its ‘shell’ has been filled with a new building used secular purposes.

St Johns Churchyard Wapping: former church

Next to the church on Scandrett Street (‘Church Street’ in the 1870s), you can see the facade of the former St John’s Old School, also now used for purposes other than that for which it was built.

St Johns Churchyard Wapping: former school

Founded in 1695, the present buildings date back to 1765. Two attractive ‘Bluecoat’ figures (sculptures), a boy and a girl, are placed above the separate entrances that were used by the fifty girl pupils and the sixty boy pupils, who attended it.

St Johns Churchyard Wapping: school detail - Bluecoat uniforms

The children who attended Bluecoat Charity Schools wore blue uniforms like those displayed on the school in Wapping.

According to one source - http://www.secret-london.co.uk:

“Blue was used for charity school children because it was the cheapest dye available for clothing. Socks were dyed in saffron as that was thought to stop rats nibbling the pupils’ ankles.”

St Johns Churchyard Wapping: school windows

Another source (https://web.archive.org/web/201307070...) provides another explanation of the blue uniforms:

“Blue is not a royal colour - that is purple; it is, however, the colour of alms-giving and Charity. It was the common colour for clothes in Tudor times, and so the charity children were dressed in blue Tudor frock coats, yellow stockings and white bands.”

In any case, the Bluecoat School standing on Scandrett Street has been closed for a long time.

St Johns Churchyard Wapping: school - detail

Although the original beautiful façades, which are well-worth seeing, have been preserved, it is used for non-scholastic purposes now.

Marine Policing Unit

Moving east along Wapping High Street, we arrived at the site of Britain’s oldest police station. It is a few steps from the Town of Ramsgate pub, where Judge Jeffries, the ‘Hanging Judge’, was ‘arrested’ by an angry mob in the 17th century. Today, a newer police station stands on the site of the original one. Entering this historic police station is something that should be avoided unless you are in big trouble!

Marine Policing Station: facade on Wapping High Street

The Metropolitan Police, which now runs this police station, dates back to 1829. However, this police station (or, to be precise, the construction of an earlier police station on this site) predates this. There has been a police station here since 1798. This is recorded by a small circular plaque on its façade. In that year, Magistrate Patrick Colquhoun and Master Mariner John Harriott, founded the Marine Police Force, London’s first ever police force, to counter the epidemic of thieving from ships moored in the port of London. Therefore, this police station stands on the site of the oldest police station in the UK, if not in the world!

Marine Policing Unit: jetty

A narrow alley leads from the street to some rickety waterside steps. From here, you can see the Police landing stage, where, I am told, any corpse dredged up from the Thames is landed before being investigated. Beyond the landing stage and across the river, you can see Rotherhithe clearly. It was from here that the “Mayflower” set forth for New England in 1620.

Marine Policing Unit; view towards Rotherhithe

We walked away from the river towards the ‘White Swan and Cuckoo’ pub on Wapping Lane, which until about 1900 was known as ‘Old Gravel Lane’. The pub was built in about 1850 and occupies a corner plot. Sunlight flooded into it. There were a few other customers, one of whom was sitting upright fast asleep during the whole time we were in there (about 45 minutes).

Turners Old Star pub

After a mid-afternoon drink, we headed to another pub, nearby, which was closed, but interesting nevertheless. This is now called ‘Turner’s Old Star’. I would have loved to have entered the building because it was where the well-known artist, and in my view one of the best ever painters, Joseph Turner (1775-1851) spent many a day and night. Turner, who was fascinated by ships, sea, and water, loved being close to the River Thames. In 1833, Turner, who never married but fathered several illegitimate children, met the widowed Sophie Booth, who was to become his mistress until he died. To maintain his relationship with her a secret, he used the name ‘Puggy Booth’ whenever he was with her. When Turner inherited two cottages in Wapping, he remodelled them into a tavern, which he named ‘The Old Star’. Turner installed Sophie as its landlady, and enjoyed visiting her here to continue their romantic affair. In 1987, the ‘Old Star’ was renamed ‘Turner’s Old Star’. A plaque on the pub describes its connection with Turner.

Turners Old Star: Turner plaque

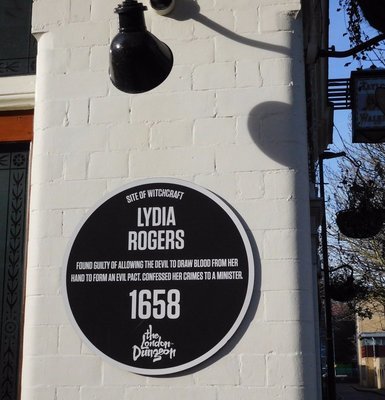

Another plaque records the memory of Lydia Rogers. She was an Anabaptist who was accused of witchcraft in the 17th century, in 1658. Lydia was a mother of two and was married to a carpenter, John Rogers. I wondered why her memorial is attached to the pub. She lived in Pump alley in Wapping, which according to an 18th century list of London's streets was off Red Lion Street in Wapping Docks. Today, what was Red Lion Street is now part of Tench Street, which is close to ‘Turner’s Old Star’ pub.

Turners Old Star: Lydia Rogers plaque

Professor Malcolm Gaskill (University of East Anglia) suggests that Pump Alley might have been the modern Meeting House Alley on which one side of the pub faces (see: https://innerlives.org/2016/10/14/hex...). He wrote of Lydia:

“This woman was accused of making a blood pact with Satan, a typical kind of diabolic union that one finds in the records, especially from the mid-seventeenth century. The devil cut a vein in her right hand to obtain the blood to use as ink for the contract. Rogers’s motive, it was said, was a lust for money. This meeting was alleged to have occurred late at night on 22 March 1658. Subsequently the minister of Wapping, Mr Johnson, spent time with her, as she lay in a diminished state, confessing to her grievous sin. She showed him the mark where the devil had drawn blood. He prayed with her, and she suffered a raving fit as the devil in her was tormented, so much so that people present in the room had to hold her down. The source for the story is “The Snare of the Devil” (1658).”

From Turner’s pub, we walked past the restored Tobacco Dock towards the border of Wapping at The Highway. Tobacco Dock was constructed in about 1811 to store tobacco. In the 1990s, it was redeveloped, hoping to make it into a recreation area, the ‘Covent Garden’ of east London. It never really ‘took off’, and has being lying largely disused since the 1990s.

We crossed The Highway to visit what Fergy aptly described as “a church within a church”.

St George in the East: Hawksmoor's church

From afar, this looks just like an ordinary church, albeit an elegant one. And, so it should be considered, because it was one of the six fine churches in London designed by the architect Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736), a clerk and student of the great Sir Christopher Wren.

St George in the East: Hawksmoor's tower

Enter the church, and then you will discover something unusual. The Hawksmoor church contains a much newer church.

St George in the East: a church within a church

The reason for this Russian doll arrangement is that during the Second World War, Hawksmoor’s church was bombed in 1941. All that remained was the outer shell and some of the towers attached. In 1964, a new church was built within the shell of Hawksmoor’s original building.

St George in the East; apse ceiling

The apse of the new church is a replica of that which existed before the bombing. For a very detailed history, see: http://www.stgitehistory.org.uk/churc....

Cable Street: street sign

The last stop on our wanderings was a place of great historical interest that I had heard about, but had never visited before. It was Cable Street, which is also a little way beyond the old boundary of Wapping.

Cable Street: a pub, now a B&B

Cable Street, near to the London Docks, was where hemp ropes were laid out and twisted into ships' cables. But, this is not what makes it so famous.

The street was a very impoverished part of London with cheap lodgings, opium dens, drinking holes, brothels, and so on. Many poor people and immigrants lived there, including a good number of Jewish people.

Cable Street mural

On the 4th of October 1936, the anti-Semitic British fascist leader and admirer of Hitler and Mussolini, Oswald Mosely, decided to organise a march of his British Union of Fascists (the ‘Blackshirts’) through the East End. Provocatively, he included the very Jewish Cable Street on his route. Attempts were made to ban the march, but it was allowed to proceed and was given police protection. The locals and many mostly left-wing sympathisers from all over London decided that Mosely and his mob were not going to be allowed to pass along Cable Street unopposed. Mosely’s opponents barricaded Cable Street, and a huge battle broke out between them and Mosely's mob. The resistance was successful. The Battle of Cable Street prevented the fascists from achieving their aims that day.

Cable Street mural: detail

The Battle has been commemorated by a wonderful mural created on one wall of St Georges Town Hall, which is on Cable Street. It was painted between 1976 and 1982 by artists including: Dave Binnington, Paul Butler, Desmond Rochford and Ray Walker. This vibrant work of art is full of symbolism, and deserves careful studying.

Cable Street: St Georges Town Hall: Civil War plaque

Most of the original buildings in Cable Street have gone. It is worth looking at the Town Hall upon whose wall is attached a memorial celebrating people from Tower Hamlets, who fought against Franco in the Spanish Civil War.

Cable Street: mural detail

Shadwell Station, served by London’s Overground, is on Cable Street, and it was there that Fergy and I ended our wonderful walk around and about Wapping.

WALKING IN AND AROUND WAPPING remains copyright of the author ADAMYAMEY, a member of the travel community Travellerspoint.

Post tags: london east-end wapping

Comment on this entry | Tweet this | Your own free travel blog | More Travellerspoint blogs

March 12, 2017

AN OASIS NEAR OXFORD STREET

I have often walked south from Oxford Street along Duke Street, and always noticed the raised pavilion with a dome on the right. It stands in what appears to have once been a square. The dome surmounts four neoclassical porticos each supported by a pair of columns with florid capitals. I have always wondered about it, but until recently did nothing about researching it. It was only lately that I explored it and its companion on Balderton Street, which runs parallel to Duke Street.

Pavilion on Brown Hart Gardens

We had arrived early in Balderton Street, where we were meeting foreign guests at their hotel, the Beaumont. With time to spare, we took a closer look at these pavilions. Staircases on either side of both pavilions lead from street level to a raised or elevated roof garden, which is about twelve to fifteen feet above street level. There is also a lift. The garden looked recently designed, and at the Balderton Street end there is a modern café that looks like an elegant glass shoe box.

Brown Hart Gardens: roof-top garden

The raised structure with its roof garden, café, and pavilions occupies the centre of a rectangular ‘square’ surrounded by mostly residential blocks on three sides and the aforementioned hotel on its fourth. It occupies the space that would usually contain a garden in London squares.

The garden and the building upon which it stands form the centre-piece of Brown Hart Gardens.

Duke Street, which runs along the eastern edge of Brown Hart Gardens was laid out on the Grosvenor Estate in the early 18th century. It was extensively re-developed in the 1870s. The Duke Street Gardens, as Brown Hart Gardens was originally named, were laid out in in the 1880s. The blocks of flats built around the gardens date from this period.

From “Survey of London: Volume 40, the Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair, Part 2 (The Buildings)”, we learn that:

“…plans were in preparation for the complete rebuilding of Duke Street and for the blocks of industrial dwellings that were to be built around Brown Hart Gardens in 1886–8. The new Duke Street appears to have been conceived as a street of shops with somewhat better-class flats over, acting as an intermediate zone between the blocks round Brown Hart Gardens to the west…”

When the gardens and its surrounding buildings were being planned, The Duke of Grosvenor, the landlord of the Grosvenor Estate, wanted (according to the Survey, quoted above):

“… to have a ‘cocoa house’ or coffee tavern and a public garden. The coffee tavern was dropped for want of an applicant, but the I.I.D.C.'s contract included an undertaking to clear a space and provide a communal garden on the site between Brown Street and Hart Street. The Duke soon took over the garden scheme except for the surrounding railings, and in 1889 it was constructed to the layout of Joseph Meston …”

The same source adds:

“…The simple garden included a small drinking fountain at the east end, a urinal at the west end and a shelter in the centre; trees were also planted. None of these features was to survive long…”

Brown Hart Gardens: GARDEN CAFE

These features disappeared as did the garden itself. For, in 1902 the street level gardens were cleared away to make way for the construction of the Duke Street Electricity Substation. Partly above ground and partly below, this electrical facility was completed in 1906. It was built for the Westminster Electric Supply Corporation to the designs of C. Stanley Peach (a leading architect of electrical installations), with C. H. Reilly as assistant. The domed pavilions at either end of it were part of the original design. The Survey describes the building well:

“As built, the sub-station rose to a greater height than had been contemplated but retained Peach's original layout, with a tall 'kiosk' or pavilion and steps at either end, a balustrade all round, and Diocletian windows along the sides to light the galleries of the engine rooms, which occupied deep basements.”

The company had managed to persuade the Grosvenor Estate to demolish the gardens because they said that they were being used by disreputable types. Of course, the presence of the new electricity building deprived the residents of the square of their garden.

The residents protested. The electricity company laid out a garden on the roof of the substation, using trees planted in tubs. According to the Survey (quoted above):

“…the 'garden' is perhaps the only place in London where quarrelling is specifically forbidden by law.”

The garden survived until the early 1980s, when the then lessees of the plot, the London Electricity Board, closed it to the public.

In late 2007, the City of Westminster decided to spend money on improving public spaces. On the 7th of December 2007, its Press Department issued a release that included the following:

“Brown Hart Gardens, which has a closed off elevated 10,000 sq foot stone deck with two listed early 20th century domed features - is one of three schemes set to benefit from a proposed multi-million renewal of the open spaces and streets surrounding three of Grosvenor's sites across Westminster….

… The proposals could see Brown Hart Gardens become a distinctive destination, opening up the square for the first time in two decades and possibly adding some much needed greenery to the area.”

The gardens were re-opened to the public after more than twenty years.

In 2012, the gardens were closed once again, but this time for a short period. They opened again in 2013, having been fully and beautifully refurbished by the Grosvenor Estate.

Brown Hart Gardens: GARDEN CAFE

The restored roof garden contains a café, currently managed by the Benugo chain. This contemporarily designed café is almost entirely surrounded by huge glass windows, making the place feel light and airy. Situated at one end of the Brown Hart Gardens roof garden, this place offers a lovely view of this horticultural oasis. So, finally, the former Duke of Grosvenor’s desire to have a café in his square has been realised.

Brown Hart Gardens water feature

The garden also contains a water feature designed by Andrew Ewing. The numerous planters (plant pots) and benches can be moved around to change the layout of this pleasant garden.

West of the gardens, there stands the Beaumont Hotel. I have not stayed here, but some friends, who were, showed us around the place, including their suite of rooms.

Beaumont Hotel: bar

Stepping into the lobby is like walking out of the 21st century and right back into the 1920s. The whole hotel is decorated in the art deco style, but it is all recently built - the hotel only opened in 2014. So, what you see is 'neo-Art Deco'. But, its brilliantly done.

Beaumont Hotel: dining room

Beaumont Hotel: a landing

Our friends' suite of rooms was also decorated in the 1920s style. It was immaculately equipped with a comfortable bed, spacious cupboards and dressing rooms, a range of magazines, a bookshelf filled with recently published books, drawers full of luxurious snacks, a coffee-maker, and so on. The en-suite bathroom was spacious and superbly equipped.

Beaumont Hotel: a hallway

This is a hotel to head for if money is no problem.

Brown Hart Gardens is only a few yards away from Selfridges and busy, crowded Oxford Street. Yet, when you reach this square, you feel as if you are miles away from the commercial chaos of London’s West End, possibly even in the heart of the countryside.

Brown Hart Gardens: view of Selfridges from Brown Hart Gardens along Balderton Street

Brown Hart Gardens provides a welcome respite from retail hustle and bustle. According to the people working in the café, few realise that it exists and it is quiet for most of the day apart from lunch time.

AN OASIS NEAR OXFORD STREET remains copyright of the author ADAMYAMEY, a member of the travel community Travellerspoint.

Post tags: gardens oasis peace selfridges hart brown

Comment on this entry | Tweet this | Your own free travel blog | More Travellerspoint blogs

March 8, 2017

WOOLWICH - above and below

My wife is a legal professional. Her work takes her to courts all over Greater London. When I am not working, I often meet her near a court, where she is working, for lunch or a snack. Recently, she was working at Woolwich County Court, near which I met her for lunch (at the good Granier Cafë in Powis Street). After lunch, I headed north a short distance to wards the River Thames.

The name Woolwich might be derived from the Anglo-Saxon words meaning 'place for trading wool'. What was once a small town used to be in the County of Kent, but is now part of the London Borough of Greenwich.

Gateway House

Within a few yards of the Thames bank and several feet above it there stands Gateway House. This magnificent art-deco building designed by George Coles and built in 1937, used to be the Odeon Cinema of Woolwich. Since about 2001, it has been used both as a conference centre and a religious centre.

Gateway House detail

Across the road from Gateway House, there stands a brick building that calls itself 'The Cathedral', or CFT Cathedral (Ebenezer Building).

Formerly, this building housed the Grenada Cinema. It was opened four months before the Odeon, which it faces, and it could seat an audience of almost 2500. Designed by a team that included Cecil Massey, Reginal Uren, and Theodore Komisarjevsky, it is now used and maintained by the Christian Faith Tabernacle. This organisation also restored what had once been a luxurious cinema to its former glory.

Theodore Komisarjevsky (1882-1954) was Russian but born in Venice (Italy). Apart from being a noted theatre director and designer, Theodore is also famous for having taught the influential Russian theatre director Konstantin Stanislavsky. In London, he designed a number of theatre and cinema interiors, of wihich the Grenada in Woolwich is a fine example.

CFT Cathedral

.

These two ex-cinemas were not actually where I was heading, but they caught my attention, and have proved to be of interest. Sadly, i was unable to enter them. My aim was to reach the nearby WOOLWICH FREE FERRY.

Woolwich Free Ferry loading at North Woolwich

There has been a ferry across the River Thames at Woolwich since the 14th century, if not before. Various ferry services crossed the river hera at woolwich between the 14th and the 19th centuries. In the same year as the Eiffel Tower was completed, 1889, the 'modern' ferry service was inaugurated using a paddle steamer. As motor traffic increased during the ealy 20th century, the idea of a bridge from Shooters' Hill to East Ham was discussed, and rejected, in the House of Commons. During the 1960s the ferry service was improved to handle the large volume of traffic more efficiently.

Woolwich Free Ferry fully loaded

In 2015, more than two million passengers (foot-passengers, vehicle drivers, and vehicle passengers) used the ferry service. Of late, pedestrian usage has decreased, but there has been no diminution of vehicle users. To this day, the ferry is FREE OF CHARGE for both vehicle users and footpassengers. This is in common with the nearby Blackwall Tunnel. Further downstream, the newer Dartford Crossings attract an ever increasing toll payment.

Woolwich Free Ferry: view of Canary Wharf and Thames Barrier

I walked down to the embarcation pier. Looking across the river you can see the northern terminal of the ferry, and also watch 'planes landing and taking off from nearbt london City Airport. Looking upstream, you get most wonderful views of the skyscrapers of Canary Wharf, and in front of them the sections of the Thames Barrier that operate the barrage gates.

Two ferry boats operate simultaneously: one leaving the north terminal at about the same time as the other leaves the southern one. I waited at the pedestrian gangplank until the ferry was ready to board.

Woolwich Free Ferry: Passenger 'gangplank' at South Woolwich

Passengers travel under cover below the car deck, which is open air.

Woolwich Free Ferry: Vehicle deck

The passenger accomodation is spacious, but a little bit 'spartan'. There are plenty of benches on which to rest during the less than five minute long voyage.

Woolwich Free Ferry passenger deck

From the passenger deck, views are somewhat restricted because there are limited openings through which to see what is outside.

Woolwich Free Ferry Ferry and Canary Wharf

The observant ferry user will not miss noticing that close to each terminal of the ferry there is a small circular building made out of red bricks.

Woolwich Free Ferry Ferry and small round, red building near southern ferry terminal

These two small, round, red brick buildings with conical roofs mark the northern and southern access points to another way of traversing the river Thames: THE WOOLWICH FOOT TUNNEL. Like the ferry, the use of this tunnel is free of charge. It is for use of pedestrians only, not cyclists.

Woolwich Foot Tunnel

Opened in 1912, the tunnel is 504 metres long, and about 3 metres below the river bed. It is fitted with a system that allows mobile telephone users to use their phones whilst in the tunnel. There are two ways of reaching the tunnel from the surface:

by stairs

Woolwich Foot Tunnel: North staircase

Or by lift:

Woolwich Foot Tunnel: Lift entrance below ground

Woolwich Foot Tunnel: inside the lift

The tunnel is for the more energetic traveller or for those who get seasick easily. It also 'operates' when the Woolwich Free Ferry is not working.

Woolwich Foot Tunnel: North Woolwich entrance

Beyond the northern terminal of the ferry at North Woolwich, I came across the OLD NORTH WOOLWICH STATION

North Woolwich Old Station

Its windows are boarded up, and from what one could see through the railings surrounding its rear, it is falling to pieces. This was once North Woolwich railway station. The lovely red bricked building that dates back to 1854 served as the ticket office until 1979.

North Woolwich Old Station: view of interior

Between 1984 and 2008, this disused station was used to house a museum. It has been closed for years. I have no idea what the future holds for this fine example of station architecture. I hope that it will not be demolished.

North Woolwich Old Station

So, what started out as being my desire to travel on the Woolwich Free Ferry has ended up as being an excursion filled with interest.

WOOLWICH - above and below remains copyright of the author ADAMYAMEY, a member of the travel community Travellerspoint.

Post tags: london river tunnel thames ferry woolwich

Comment on this entry | Tweet this | Your own free travel blog | More Travellerspoint blogs

February 11, 2017

VISITING VYPIN ISLAND - a lovely excursion from Cochin

Chinese fishing nets, Fort Cochin

Chinese fishing nets, Fort Cochin Goat on a boat: on the ferry from Vypin to Fort Cochin

Goat on a boat: on the ferry from Vypin to Fort CochinLike Venice and Istanbul, Cochin is a city where water plays an important role both functionally and aesthetically. The Cochin ‘metropolitan’ area that includes Fort Cochin, Mattancherry, the modern city of Ernakulam, Willingdon Island, and other islands is infiltrated with waterways that flow past them and out into the Arabian Sea. These watery channels are alive with shipping, lined with fishermen, flanked by warehouses, and swarming with waterfowl. The sun reflects off the waters, producing a rare quality of light that heightens the beauty of the area.

The historic city of Fort Cochin with its many historic buildings, its Chinese fishing nets, and its colourful shoreline, makes for a wonderful place for tourists to linger. I have visited the place three times in two years, and Cochin’s attraction simply continues to grow for me.

The elongated island of Vypin (aka ‘Vypeen’) runs in a north-south direction, its southernmost tip being across the estuary from Fort Cochin. Two ferries connect Vypin with Fort Cochin. One carries foot passengers only, and the other carries both vehicles and foot passengers.

Ticket office for ferry at Vypin

Ticket office for ferry at VypinThe first time that I crossed to Vypin on the foot passenger only ferry, I noticed that a section of the boat was reserved for ladies only. Indeed, the queues for the ticket boot were segregated by gender. Lately (2017), I did not notice any separation of male and female passengers.

Leaving Fort Cochin, the ferry passenger gets a good view of the Chinese fishing nets on one side, and of the waterfronts of the Brunton Boat House and its neighbours (such as the old Aspinwall warehouse complex).

The ferry captains have to navigate carefully, so as to avoid colliding with all manner of craft: everything from ocean going liners and enormous dredgers to tourist pleasure boats and smaller craft used by the local fishermen.

Boats moored at Vypin

Boats moored at VypinAs the Fort Cochin shore begins to recede and mingle with the heat haze, the Chinese fishing nets of Vypin get nearer. Behind them, it is not difficult to see a couple of huge cylindrical structures, which are part of an oil refining site near to the Arabian Sea shore.

Belts in a small shop in Vypin

Belts in a small shop in VypinBoth ferries dock at the aged, rather shabby Vypin ferry terminal, which until recently contained an even shabbier café, The Sealand, now closed. Passing through the terminal, we reach a line of small shops that face a parking area where multi-coloured busses and auto-rickshaws park. These busses carry passengers to a variety of places including Ernakulam and beaches at the northern tip of the island.

Detail on a private house in Vypin

Detail on a private house in VypinThe southern shore of Vypin is a peaceful contrast to the relatively busy shore of Fort Cochin, which faces it across the water. A good paved footpath follows the shoreline, passing several Chinese fishing net set-ups, upon whose ropes and wooden structural elements sea birds roost. On a recent visit, most the avian population consisted of white egrets. Landward of the path but partly hidden by the dense foliage of luxuriant gardens, you can just about spot low dwellings.

Taking one of the paths that lead away from the sea, one enters a series of narrow lanes lined with domestic residences surrounded by lush gardens. Wandering around these lanes reminded me of the lesser visited parts of Venice. There was hardly anyone around, little or no traffic, and a lovely calm silence.

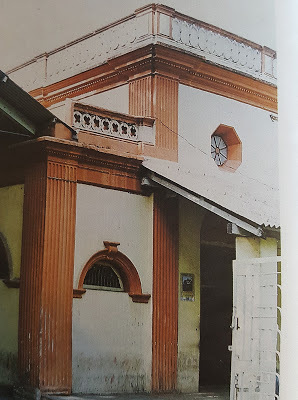

The village of Vypin is built around The Church of Our Lady of Hope, (aka "Nossa Senhora Da Esperança"), which was built during the Portuguese occupation in 1605 AD (see picture above). Along with many other Roman Catholic buildings in the Cochin district, it was badly damaged by the Dutch in 1663, but has been restored lovingly since then. Usually this is closed except for early morning masses. My wife managed to persuade a passing nun to get the sacristan to open up the church for us. While its interior (see picture below) is not as grand as some of the churches we saw in Goa, it is nevertheless worth seeing. A great anchor hangs from the northern wall of the chancel. A highly-revered effigy stands in a glass-fronted cabinet covered with a curtain near the southern wall of the church.

A short walk through more narrow lanes brings one back to the ferry station. Whereas the passenger only boat is quite comfortable for passengers, the boat that carries vehicles is less so. Passengers congregate at the covered foremost part (the bow) of the boat. Cars and vans are tightly loaded onto the ferry, and then the two wheelers motor bikes and scooters) squeeze their way into the remaining spaces including at the bow of the ship where foot passengers congregate, trying to avoid being knocked by mirrors or getting their feet run over by wheels.

Disembarking, one realises how peaceful Vypin is in comparison with Fort Cochin. This is not to say that Fort Cochin is not particularly unrestful (as is the city of Ernakulam); it is just far busier than that peaceful haven Vypin.

The vehicular ferry at Fort Cochin

The vehicular ferry at Fort Cochin

Now WATCH a short video showing a crossing from Fort Cochin to Vypin by CLICKING HERE

Church hall on Vypin Island next to Church of Our Lady of Hope

Church hall on Vypin Island next to Church of Our Lady of Hope

DISCOVER ADAM YAMEY's BOOKS by clicking: H E R E

December 15, 2016

EDWARD LEAR IN BANGALORE

Telicherry (Kerala) sketched by Edward Lear in 1874

On September, the 24th 1874, Mr Edward Lear (1812-1888), who was staying in Bangalore (now ‘Bengaluru’), wrote in his diary: “Walked to Orr and Barton’s and got my photographs…”

Lear is best known for his nonsense verse, lesser known as an artist. Although never as successful as his contemporaries (e.g Holman Hunt, Lord Leighton, Alma-Tadema, Turner, Millais, and Rossetti,) in the 19th century UK art world, he was a wonderful landscape artist. In addition, he was highly skilled at depicting flora and fauna (especially birds: he was said to rival Audubon). Oddly, his talents did not extend to great representations of the human form except in comical cartoons, at which he excelled.

Restless, Lear travelled the world in search of the ‘picturesque’. He visited many places, including Albania, which is what got me interested in him in the first place. He recorded his travels in sketchbooks, and later transformed some of these into oil paintings - the medium which he hoped to master - but never really managed. Lear described his trips in diaries that he later published as travel journals, his pen producing portraits of the places almost as eloquently as his fine sketches and watercolours.

Recently, I discovered that Lear visited India (including Ceylon). He did so at the invitation of an old friend, Thomas Baring - Lord Northbrook, who had become the Viceroy of India in 1872. I bought a reasonably priced second-hand copy of Lear's "Indian Journal", introduced and edited by Ray Murphy (published in 1953). Unlike his other travel journals (e.g. for Albania, Greece, Corsica, and Southern Italy), this book contains Lear's actual diary entries rather than a later polished-up literary version of them.

Lear describes almost every day of his trip to India, which lasted from November 1873 until January 1875, when sickness and bad back pain forced him and his Albanian servant Giorgio to end their rambles, which had taken them from the heights of the Himalayas to the deep south of India and through Ceylon.

The trip was dogged with problems: logistic, illness, food, and so on. Yet, even on the worst of days, Lear found something redeeming to write about. Lear enjoyed Indian 'local colour', but was often less than lukewarm about British colonial social life. He preferred the ‘really Indian' places to those places favoured by the British. Many a place where the British liked to spend time relaxing were loved because, to use Lear's words, because of their: “un-Indian qualities."

Lear visited Bangalore twice. His first sojourn was between the 13th of August 1874 and the 21st of that month. He arrived there on a train that passed through: “Arkonam … at the junction of the Bombay-Madras and Madras-Malabar lines.” At this his junction in Tamil Nadu, now known as ‘Arakkonam’, he had to spend a night in a waiting room. In Bangalore, he took rooms for himself and his servant in the Cubbon Hotel, which he did not rate highly on arrival. However, a few days later, he noted:“The food at this hotel is good, and the service quiet and unobtrusive…”Kora Chandy wrote in “The City Beautiful” by TP Issar (published1988): “…let me turn to Infantry Road and the present office of the Commissioner of Police. Some 100 years ago, it was the leading hotel in Bangalore, called the Cubbon Hotel. The facilities it advertised included a ball room, ‘complete suites of the bachelor’s apartments’ and ‘carriages on the premises. In the early years of the century the British Resident purchased this property and his office was located there until 1928…” In 1911, the Cubbon Hotel still existed, when it was leased by Spencer’s, which was then in the hands of the Oakshott family. The Cubbon Hotel was rated along with the (still extant) West End Hotel as being above average in Murray’s “Handbook for Travellers in India, Burma, and Ceylon” (10th edition, published 1920). Therefore, the Resident must have purchased it sometime after 1920. Maya Jayapal writes in her “Bangalore: roots and beyond” (published in 2014):“… the Cubbon Hotel… was constructed in the prevailing style of colonial architecture, sometimes called Greco-Roman. It is now the police commissioner’s office…”A photograph (see below) in TP Issar’s book confirms Jayapal’s description of the architecture.

Lear considered Bangalore: “… an odd place, not over beautiful, but contains three picturesque bits and, I think, one general view. The tall coco-palms are a chief characteristic, but the queer houses are odd indeed…”On the 15th of August, he visited the Lal Bagh gardens, concluding that: “… he had never seen a more beautiful place, terraces, trellises, etc., not to speak of some wild beasts. Flowers exquisite… There is something very rural quiet about this place… walked with Giorgio to some granite rocks, and a little tank, where I drew till it began to rain, ven I cum back…”This little excerpt exposes Lear’s liberated approach to spelling. I have visited Lal Bagh often, and have seen its large tank, which contains an island. The large tank is separated from a smaller one, often filled with waterlilies, by a causeway. I am not sure about which water feature Lear was writing. Next day, he visited Ulsoor Tank, but arrived too late to sketch it. The Tank, which is still in existence, is a veritable lake with several islands in it. Zafar Futehally and Kora Chandy writing in Issar’s book, noted:“It extended over an area of 125 acres and was constructed by Kempegowda II during the second half of the 16thcentury.”It supplied drinking water to the civilian and military population of Bangalore until the 20th century.That day he praised Bangalore in his diary: “This station is very extensive and populous, and seems in some ways the pleasantest I have known in India. A sort of homely quiet pervades everything, and the air is delightful, ditto flowers. Birds are numerous but make absurd noises.” All over India, Lear remarked on the peculiar birdsong he heard. He left Bangalore on the 21st of August, heading for Madras.

Lear returned to Bangalore on the 23rd of September 1874, arriving by train from Salem. His journey had not been uneventful. Near ‘Cajdoody’ (this is probably modern day Kadugodi, which is on a railway close to Whitefields, and, relevantly, a couple of still-extant large bodies of water), a bridge was down. Lear wrote:“Descending from the carriage, we had to walk along a narrow edge of clay by the steep side of the embankment; this was … difficult. … Next, a descent, with a crowd of natives, and still more awkward pass over loose planks to a boat … ferried across deep and rapid water, the result of a broken tank which had so swollen the stream as to carry away the bridge. Then came a hoisting up slippery wooden steps … to the level of the other train…” Lear and Giorgio arrived exhausted in Bangalore on the 23rd of September 1874 after a thirty-minute train journey from the flooded area. It was the following day that he visited Orr and Barton’s to collect some photographs – of what he does not say. Throughout his visit to India, Lear bought photographs, which he might have used to remind him of places that he had seen.

On my last visit to Bangalore in 2016, I bought some jewellery from Barton’s, whose extensive shop is within Barton Tower on MG Road. From its earliest days, it had been a jeweller but it came as news to me that it was also known for its photography. The 1920 Murray’s guide to India (see above) lists “Barton & Sons” both as a jeweller and a photographer. One of the Mr Bartons must have been an exceptional photographer. M Fazlul Hasan writes in his “Bangalore Through the Centuries” (published 1970) that when an equestrian statue of Sir Mark Cubbon was unveiled in March 1866, many photographers rushed forward to ‘snap’ it, but:“Owing, however, to the fading light and other difficulties, only two, Major Dixon and Mr Barton, succeeded.”

Bangalore was not Lear’s last port of call in India. He went on to visit several other places including Sri Lanka before returning via Kerala to Bombay, and thence back to Europe. It was noticing that he had visited Barton’s, a shop I know well, that prompted me to write this piece based on the lesser-known travels of a well-known cultural figure of the nineteenth century.

READ FASCINATING BOOKS/KINDLES BY ADAM YAMEYDISCOVER MORE by clicking: H E R E !

November 24, 2016

DESIGN MUSEUM IN LONDON

CLOTHES WITHOUT AN EMPEROR

In 1837, the Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen wrote his “Kejserens nye Klæder” (‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’). Two tailors weave some new clothes for the Emperor. No one can see them because they were invisible, they had no substance at all, they did not exist.

London’s Design Museum has just (November 2016) moved into what used to be the Commonwealth Institute (‘CI’) in Holland Park. Its construction was completed in 1962. I remember visiting the CI in the early 1960s, when its gloomy interior housed exhibits from various parts of the Commonwealth. I was more impressed by the building’s then original and fantastic architecture than by its contents.

The CI building remained closed and disused from long before the beginning of this century until this year when it re-opened as the Design Museum. The building’s exterior has been well-restored, but is somewhat hidden from the road by two ugly ‘rectanguloid’ (or box-like) low-rise tower blocks, which are an affront to both good design and good town-planning. I imagine that letting or selling space in these two buildings helped pay for the restoration of the former CI building.

The interior of the old CI building has been scooped out and replaced by a wonderful new interior, an exciting space worthy of a museum that is dedicated to design.

Sadly, the exhibition fails miserably. Leaving the splendid atrium, the visitor enters a series of ‘galleries’ crammed with ‘icons’ of (mostly) 20th century design. The cluttered exhibition spaces reminded me of charity shops or jumble sales. The only difference between the museum and the latter is that the objects on display are in better condition than those in jumble sales or charity shops.

The newly located Design Museum made me think of Hans Christian Andersen. The building is splendid, both outside and inside, but the exhibition does not deserve such a fine building. The clothing is great, but the Emperor is missing.

CLICK ABOVE TO SEE A VIDEO OF THE MUSEUM'S INTERIOR

VISIT ADAM YAMEY's WEBSITE TO DISCOVER MORE OF HIS WRITING

November 15, 2016

DISCOVERING JEWS IN BANGALORE

About ten years ago, an American Jewish acquaintance, who had just completed a tour of southern India, complained that he had seen no end of Hindu temples and Christian churches, but only one synagogue. Well, I was not surprised. Once in Venice (Italy), a religious Jew on learning that I am Jewish asked whether my wife (a gentile), an Indian, is Jewish. That got me thinking. I calculated that randomly meeting a Jew born in India was extremely improbable – it is less than 0.0005%. So, to write about the Jews of India is to describe a minute proportion of the country’s vast population. And as I write, that proportion is only likely to diminish.

While idly flicking through the Eicher street atlas for Bangalore, I noticed, quite by chance, that the city has a “Jewish Grave Yard”. I have visited this cemetery several times. It contains less than sixty graves, but together they open a window that provides a good overview of the Jewish people who have lived in India. The story of India’s Jewry has been described in detail elsewhere (for example: “India’s Jewish Heritage” edited by Shalva Weil and “Shalom India” by Monique Zetlaoui). I will present their tales as viewed through a south Indian lens.

Jews have lived in what is now Kerala since time immemorial. They lived on the Malabar Coast in, for example, Kranganore and Cochin. It is said that St Thomas came to India to convert them into Christians. He failed miserably, converting, instead, the other people who he found living there. A grave in the cemetery commemorates Elias Isaac, who came from Cochin to Bangalore to act as the schochet(ritual slaughterer) to the Moses family. Today, there are one or two elderly Jews still living in Kerala.

The oldest graves in the cemetery mark the resting places of Subedar Samuel Nagavkar (1816-1904) and Benjamin Nagavkar (1877-1910). Samuel might have served the Maharaja of Mysore, Krishnaraja Wodeyar, who donated the land for the cemetery in 1904. The Nagavkars were members of the Beni Israel community, whose origins are obscure. According to the historian HS Kehimkar, they claimed to have come from “the North” to India in about 175 BC (BCE). Many of their community still live in and around Maharastra State.

There are several other graves bearing names of Beni Israel Jews. Tor example: the horse trainer Sion E Nissim (1900-58), one of whose horses, Commoner, won the Indian Derby; Mrs Abigail Jhirad, daughter of the Subedar; and Joshua Moses Benjamin Bhonkar (1920-2005). The latter (aka ‘Joshua Benjamin’) was both a writer (“The Mystery of Israel's Ten Lost Tribes and the Legend of Jesus in India”) and a Chief Minister in the Government of India.

Whereas the origins of the Malabar and Beni Israel Jews are obscure, this is not the case with the Iraqi Jews, who came to India from the Middle East beginning in the 18thcentury. Many of them settled in Bombay and Calcutta. The most famous of them being the Sassoon family.

The Bangalore cemetery contains graves for the following families from Calcutta: Ezra, Elias, Earl, and Moses. Edward Earl (1910-1953) was the proprietor of the once well-known Earl’s Pickles company. Calcutta used to have a large Jewish community, including the Moses family, who are buried in Bangalore and originated in Iraq.

Ruben Moses (1871-1936) left Iraq to join the California gold rush. He left California for India in 1906, following the disastrous San Francisco earthquake. He headed for the Kolar gold fields, but ended up in Bangalore, where he founded a shoe store in the city’s Commercial Street. The store, which is now occupied by Woody’s veg fast-food outlet, was once the largest shoe retailer in southern Asia. His home, now long since demolished, contained a prayer hall where the city’s few local Jews and Jewish visitors from all over the world came to wordship along with the Moses family.

What did the Jews do in Bangalore apart from what I have mentioned above? Poor Moses Ashkenazy(1957-1982) was a student, who died of an overdose of drugs. Sassoon Saul Moses (d. 1975) was a ‘hawker’, as were many of my Lithuanian Jewish ancestors who arrived in South Africa in the 1890s. The widow Rebecca Elias (1927-1992) lost her husband early, and then worked in a needle factory in Bangalore. GE Moses and Isaac Cohen, neither of whom are buried in the cemetery, were, respectively, a clothes retailer and an auctioneer. The grave of RE Reuben (1877-1939) records that he was “Malarial Supervisor of the C&M Station Municipality”. I wonder whether he ever met the Nobel laureate Sir Ronald Ross (1857-1932), the pioneer of the fight against malaria. Reuben’s place of work is mentioned in Ross’s papers.

Troubles with anti-Semitism in Europe and, later, the outbreak of the Second World War (‘WW2’) led to other Jews entering the Indian Judaic scene – refugees and soldiers. They are well represented in the Bangalore cemetery. But, before describing some of them, let me not forget the Russian-born Saida Abramovka Isako, who died in 1932. She was the wife of FY Isako, who was proprietor of the ‘Russian Circus’. Her coffin was carried on a bier drawn by white circus horses. I imagine that the burials of the German refugees Siegfried Appel (1906-1939) from Bonn, Gunther and his mother Mrs Rahmer from Gleiwitz, and Dr Weinzweig, were less memorable. Carl Weinzweig (1890-1966) was a dentist (his surgery was in MG Road), as was Gunther Rahmer.

Amongst the military personnel that passed through Bangalore during WW2, was the future President of Israel, Ezer Weizman, who was stationed at an RAF base in the city. His name appears in the Moses family guestbook. Sadly, the cemetery records the casualties of war, who died in the city. These include Yusuf Guetta (1921-1943), who was evacuated from Ben-Ghazi in Libya by the British in 1941, and Private Morris Minster (1918-1942). Minster served in the South Wales Borderers Regiment and was initially buried in the grave yard. His stone remains, but he has been moved to a large Commonwealth war cemetery in Madras.

The “Jewish Grave Yard” in Bangalore encapsulates the story of the larger of the Jewish ‘groupings’ that have lived in India. The cemetery is so unknown that even a few of the Jews who have lived in the city have been unaware of it. I have met the heirs of the Jewish refugee from Germany, Mr Jacoby, who introduced popcorn and machines for making it to India and settled in Bangalore. Their nearest and dearest are resting in peace in Christian cemeteries, of which there is no shortage in Bangalore.

At the beginning, I mentioned that India’s Jewish population is diminishing. Over the years many Jews left India. My wife, who went to school in Calcutta, remembers that the city had many thriving synagogues and that there were several Jewish girls in her class. When we visited Calcutta four or five years ago, we saw three synagogues. Two of them were well-maintained, by Moslem caretakers, as is Bangalore’s Jewish cemetery. The third that we saw appeared to be about to crumble.

India can be proud to remember that, unlike so many other countries, it was not anti-Semitism that caused Jews to migrate. Just as so many other Indians have left the country to better their economic prospects, so did the Jews.

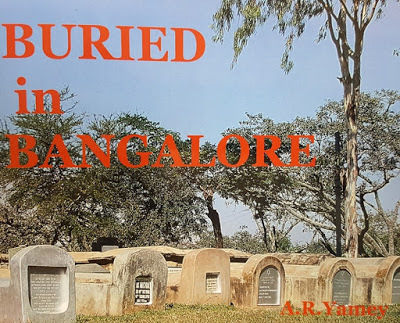

An album containing annotated photographs of all of the graves in Bangalore's 'Jewish Grave Yard' may be purchased as an e-book (or a paperback) by clicking HERE

November 8, 2016

EXPLORING ALBANIA

"REDISCOVERING ALBANIA"

A new book about Albania by Adam Yamey

Albanian people live all over the Balkans and in the Middle East, not to mention those who have migrated to Western Europe and the USA in the last two centuries. Subjects to a series of foreign rulers over the millennia, some of them now live in independent countries, which are governed by Albanians: the recently formed Republic of Kosova (‘established’ 2008), and the longer-established Republic of Albania (‘established’ 1912). Adam Yamey’s book, “Rediscovering Albania”, is about the latter, although some references are made to the former.

Adam, who has been interested in the Balkans – especially Albania – for many decades, first visited Albania in 1984, when the country was governed by a repressive regime headed by Joseph Stalin’s fervent admirer, the dictator Enver Hoxha (1908-1985). The country was then ‘hermetically’ sealed off from the rest of the world, even more so than North Korea is today. The only way for a tourist to visit Albania in 1984 was on a closely supervised guided tour during which the Albanian authorities did their best to ensure that the visitor only saw what they wanted. Their aim was to send tourists home with the impression that Albania was a ‘paradise’, which other countries ought to envy and emulate. In order to create that impression, the foreign visitor was not allowed to talk to, or otherwise communicate with, Albanian citizens; not allowed to stray from the tour group; not permitted to eat in the presence of Albanians; not allowed to take photographs of whatever interested him or her; not permitted to carry certain reading matter including religious works; and so on. Despite these restrictions, Adam came away having had an interesting view of the most beautiful country in the Balkans.

Enver Hoxha died in 1985, and was replaced by Ramiz Alia. Five years later, two years after the Berlin Wall was officially breached, Albania’s Stalinist dictatorship ended. For the first time since independence in 1912, Albanians began experiencing the closest they ever had to true democracy. In the beginning, it was not easy. During the early years of Albania’s post-Communist existence, there were many problems to be faced. For example: complex internal politics; the break-up of its neighbour, the former Yugoslavia; a civil war in 1997; Kosova’s struggle for independence.

In May 2016, Adam paid another visit to Albania. He and his wife hired a car and toured the country extensively – from the high mountains in the north to the Greek border in the south and the Macedonian border in the south-east. On this trip, Adam and his wife could: talk with any Albanian whom they met; travel wherever they wished; eat and drink with Albanians; take photographs without restrictions; carry whatever reading material they wished; and so on. They came away from the country with favourable impressions and happy memories.

During his latest trip, Adam kept a detailed travel journal. This formed the basis for writing “Rediscovering Albania”. The book charts Adam’s trip through Albania, providing personal anecdotes and observations that give the reader an idea of what to expect when visiting the country. But, there is much more. Wherever Adam went, he heard things from people, and saw sights that aroused his curiosity. On his return to London, he investigated what he experienced in detail. “Rediscovering Albania” describes Adam’s trip in the context of: Albania’s troubled history and vibrant present; the reports of earlier travellers (Francois Pouqueville, Lord Byron, Edward Lear, Edith Durham, and many others); and the opinions of Albanians, whom the author met during his journey. Also, the book includes comparisons of how the author found Albania in 1984 with what it is like today in 2016. The resulting text is an informative and entertaining introduction to one of Europe’s most fascinating, but undeservedly lesser-known, countries.

The book, which is available as a paperback and an e-book (Kindle format), contains two maps and many photographs.

As Adam took far too many pictures to be included in one book, he is posting them gradually on a Facebook page (which can be accessed and viewed by those who have no Facebook account). Visit: http://www.facebook.com/albanian2016images/

To buy a copy of the paperback: click HERE

To buy the Kindle: click HERE

September 17, 2016

A bunker in south Albania

Bunker by Lake Ohrid, near Pogradec

Most of the defensive bunkers constructed in Enver Hoxha's Albania were in the form of hemispherical concrete domes (see illustration below).

Here, I describe an unusual one that I saw next to Lake Ohrid, just north of Pogradec.

Typical Hoxha era bunkers (near Lin)

Near the village of Memelisht (north of Pogradec), we examined the huge bunker on the lakeshore (illustrated above). It was like an elongated egg in plan. Part of it protruded into the lake, and the rest caused the road to curl around it. Its entrance faced inland. 2 gun slits faced north - one slightly towards the west and the other slightly towards the east. A third faced south towards Pogradec. I peered inside, and saw a central passage with doorways leading to 3 side rooms. The corridor was clean and painted white. A few discarded bottles lay on its floor. This ‘bunker’, which was so different from other bunkers that we saw in Albania, puzzled me. Valent at the hotel believed that it had been built by the Italians to control the road between Elbasan (and the north of Albania) and the south of the country as well as Greece. This seemed a reasonable explanation for its existence and positioning.Does anyone know exactly who built it. Was it the Italians, the Albanians, or someone else?Now, please visit: Adam Yamey's website

September 11, 2016

M E T R O P O L I S

There are 2 places in London that remind me of some of the sets in Fritz Lang's film "Metropolis" (1927): the common parts (vestibules etc) of the Barbican Centre and the escalator hall of Westminster Underground Station ( rebuilt in 1999).

At Westminster there is an interchange between the Jubilee Line and the Circle/District Lines. The sub-surface Circle/District lines are separated from the far deeper Jubilee Line by a series of ecalators. The latter are housed in a huge concrete lined space. The whole ensemble is grey and gloomy, lit by lights that both illuminate and at the same time emphasise the gloomy nature of this futuristic collection of escalators, steel tubes, and other structural elements. I use the word 'futuristic' with reservation as this place resembles, as already mentioned, the sets of a film made back in 1927.

Full of human life, this interconnecting hall is rather inhuman - a collection of machines for moving hordes of people from A to B. It reminds me of factory assembly lines. Worth visiting because it is an extrordinary visual and psychological experience - and because it helps you to travel through the metropolis.

READ MORE OF ADAM YAMEY'S

WRITING

HERE