Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 235

June 28, 2014

PAINTING ALBANIANS IN SICILY

Most tourists visit the small town of Palazzo Adriano to see its perfectly preserved old piazza with its unusual fountain, where the delightful movie Cinema Paradiso was filmed in 1988. We visited it for another unrelated reason. The picture below, a copy of a photograph in one of the town's museums, shows a scene from the film. The fountain is on the right side

Detail of the fountain as it is today

Palazzo Adriano is one of the 5 places in Sicily that were settled in the 15th century by Albanians fleeing from the Ottoman invaders of their homes in the Balkans. The first Albanians to arrive there were soldiers and their families, who left the Balkans before the death of their great leader Skanderbeg in 1468. More of them arrived later, bringing with them the traditions and practices of the Eastern Orthodox (Byzantine) Church. The plaque shown below, which is on the side of the town's largest Byzantine rite church, reminds us that the Albanians who came to Palazzo helped defend western Christianity from the ravages of the Ottomans.

The largest of the 5 places settled by the Albanians in Sicily is Piana degli Albanesi, someway north of Palazzo. In Piana, more than 95% of the inhabitants speak Arberesh, which is a dialect of Albanian. In Palazzo, no one speaks it anymore, but many people worship according to the Byzantine rite. We learnt this when we asked some old men who were spending time in the town's small 'Circolo Skanderbeg'. This place was filled with items relating to the town's Albanian connection. Even the lace curtain over its window was embroidered with the two-headed eagle of Albania:

The town boasts a museum of Albanian culture, the MUSEO DELLA CULTURA ARBERËSHE. It is housed in part of the castle, which overlooks the town. This grandly named institution displays only a few exhibits. Amongst these, there are a few traditional costumes that, we were told, were copied from paintings of the Arberesh made by the French artist Jean-Pierre-Louis-Laurent Houël (1735-1813).

Portrait of Houel by François André Vincent (Source: http://mbarouen.fr/en/oeuvres/portrai...)

Best known for his painting of the siege of the Bastille, he visited Sicily between 1776 and 1779. During his travels there, he painted and drew many pictures of what he saw. Many of these were bought by Russian royalty, and are now to be found in the Hermitage Gallery in St Petersburg (Leningrad). The museum in Palazzo has copies of two of these pictures, both depicting Arberesh women in traditional dress. They are illustrated below:

The marks with the crown in the lower right corners of these copies shows that they are also part of the Hermitage collection. The lower of the two pictures shown above shows what Palazzo Adriano looked like when Houël visited it. The picture below shows a part of the piazza as it is today:

We visited Palazzo Adriano hoping to find evidence of its Albanian past, and did. Even if you have no interest in the Arberesh or Albania, this well-preserved little town in the heart of western Sicily deserves a visit.

TO DISCOVER MOREWRITINGBY ADAM YAMEY,

Click H E R E

Published on June 28, 2014 07:19

May 5, 2014

CHARLIE CHAPLIN WAVED TO ME

The captions to this and the rest of the pictures in this article may be discovered by reading Adam Yamey's Charlie Chaplin waved to me

Capturing memories of youth...

"The attic of my parents’ house in north Londoncontained a number of old Revelation suitcases. These were plastered with ageing colourful paper stickers bearing the names of shipping lines and also of places such as: Cape Town, Southampton, Harwich, New York, Montreal, and Rotterdam. Had they been animate and able to speak, what tales they would have been able to tell!

If, as a child, I had become a suitcase, I too would have been covered with an exotic assortment of stickers including some of those mentioned above. But, I did not become a piece of baggage, and the stickers that I carry are not made of paper. Instead, they are memories stuck in various compartments of my brain. Unlike the inanimate objects in the attic in the eaves of our house, I am able to speak: to divulge my impressions of the places that I visited in my childhood; to describe the remarkable people I met in those places; and to reveal the unusual experiences that resulted from travelling with my learned father and my talented mother."

Adam Yamey's latest book, Charlie Chaplin waved to me, contains his memories of the holidays and trips that he took with his parents, mostly during the first eighteen years of his life.

They are worth relating because they differed markedly from the kinds of holidays that most people took during the 1960s and 1970s. Rather than exposing their children to the sun on the beach, his parents preferred to expose their 'kids' to cultural experiences that, they hoped, would benefit them in the future. This was due to Adam's father’s great interest in the history of art, which resulted from his mother having been an artist. Whereas now he appreciates what they did for him then, he did not always do so at the time ...

Here is a very brief extract from the book:

" ... my mother noticed a gondola draped with green cloths pulling up at the corner where the nearby small side canal, which ran alongside the Pensione Seguso, met the much larger Giudecca Canal. The gondolier, a young man, was dressed in green livery that matched the drapes on his highly polished black boat.

Soon after this gondola had moored, we noticed our elderly American fellow diner emerging from the main entrance of the Calcina. He headed straight for the recently arrived gondola, and then boarded it. Next, he sat down, and then started reading a newspaper whilst the gondolier began to row him across the Giudecca Canal. We watched his gondola crossing the water until it disappeared into one of the small canals that traversed the Giudecca Island. We were fascinated and intrigued. After he was out of sight, we began our morning’s activity.

My mother was never shy when she needed to know something. So, after lunch that day, she stopped our mysterious American lunch neighbour and asked him about the gondola and its liveried oarsman. He explained that everyday, he was ferried out into the lagoon in the gondola. When he reached the lagoon, he took over the oar and rowed around the waters of the lagoon for an hour before handing the oar back to the gondolier, who then rowed him back to the Calcina in time for lunch. Remarkable as it was that a non-Venetian could row a gondola competently, what he told us next was even more amazing.

Mr Milliken, as he identified himself, was, as my father was most excited to learn, none other than the director of the well-respected ClevelandArt Museum in the USA. The liveried gondolier, who we had observed, was the grandson of his late mother’s personal gondolier. She used to accompany Mr Milliken on his annual visits to Venice before WW2, and employed her own gondolier during her stays. "

"Charlie Chaplin waved to me"

by Adam Yamey

is available from:

WWW.LULU.COM

AMAZON (including KINDLE)

BARNES & NOBLE (Soon)

Published on May 05, 2014 03:21

April 19, 2014

PRESPA - WHERE THREE COUNTRIES MEET

I have been passionately interested in Albania since about 1965. Until 1984, when I visited Albania, I spent a great deal of time visiting places from which I could catch even a distant glimpse of the country. One of these places was the area containing the Prespa lakes in the north-western corner of Greece. There are two of these lakes: the Small and the Great Prespa lakes. The smaller one shares its waters between Greece (mainly) and Albania. The larger one shares its waters with Greece, Albania, and FYROM (formerly the Yugoslav Macedonia). The lakes are separated from each other by a thin strip of land, which is currently Greek territory.

Heading west along the strip of land separating the Great Prespa Lake (right) from the Small Prespa Lake (left)

In 1977, I visited the Prespa area with my parents in a chauffeur driven car. We left the main road that connects Florina with Kastoria somewhere near to the village of Vigla and joined a winding rough surfaced mountainous side-road that led more or less in a western direction. A few metres along it, we had to stop at a police post. An official recorded our car registration and our names in a huge old-fashioned ledger, and then allowed us to proceed. We had just entered the sensitive border area of Greece close to Albania.

Map of the Prespa lakes area showing places mentioned in this article.(The arrows show my approximate itinerary in 1977).

In 1977, Albania and Greece were still technically at war with each other. One of the causes of this was the Albanian claim that northern Epirus (Çamëria, in Albanian) should be returned to the ethnic Albanians, who had been expelled from it. I get the impression that the problem remains unresolved even today, at least in the minds of some Albanians.

Aghios Germanos

The road we followed wound through wild mountainous terrain. Eventually, we arrived in the tiny village of Aghios Germanos. It had a deserted appearance as we stared at it in the midday sun. Nobody was about. From there we made our way to the neck of land that separates the two Prespa lakes. We stopped along it to have lunch - I believe that we ate fish -at a small restaurant.

The strip of land separating Great Lake Prespa (in the background) from LittleLake Prespa. Adam Yamey is on the right of the group in the photo.

From where we stopped, we could see the peaks of Albanian mountains in one direction.

Great Lake Prespa. The distant headland in the right third of the picture and the barely visible mountains behind it are in Albania.

And, in the other direction we could see the distant hills of Macedonia.

Great Lake Prespa looking east towards the mountains of Macedonia (FYROM)

As we drove away from Great Prespa, we began to get good views of Little Prespa

Little Lake Prespa

We left the Prespa lakes region by way of a different road from that which we arrived there. We rejoined the main road that connects Florina with Kastoria near to the village of Trigono, where we stopped because I wanted to take a photograph of the monument whose illustration appears at the beginning of this article.

Trigono village

I had completely forgotten that I had taken this picture in 1977, and only rediscovered it this April (2014). The simple monument in white stone bears an inscription, which I have illustrated below:

My rudimentary knowledge of the modern Greek alphabet allowed me to decipher the subject's name as "Skountris Emmannou??" In vain, I searched for this name or variations of it on the Internet. Next, I wrote to my relatively new acquaintance Professor Christina Koulouri in Athens. She told me that this statue was put up in memory of a Cretan volunteer, Emmanouil Skountris. Furthermore, she informed me that he was a Greek fighter during the 'Macedonian Struggle' (1903-1908).

In brief and at the risk of gross oversimplification, the Greeks were fighting the Bulgarians to gain control of Ottoman Macedonia. There is very little about Emm. Skountris on the internet, but what follows is what I have managed to discover so far.

Trigono is known as 'Osčima' by the Bulgarians. On the 14th September 1904, Greek rebels led by the Cretan Efthimios Kaoudis fought with Bulgarian rebels at Trigono. The Greeks won this battle, but amongst the injured was Emmanouil Skountris.

A Bulgarian web-site ( click here) contains six lines of text about Skountris as well as the picture reproduced above. Using a computerised translator and a little common sense, this is what they say:

"Emmanuel Skundris Adele was born in Crete. He entered the ranks of the Greek propagandists in Macedonia in 1904, joining the the band of Evtimios Kaudis. He took part in the fighting near Kostenariyata and was slightly wounded at the Battle of Oshtima on September 14, 1904"

The variations of spelling are to be expected when transliterating from one alphabet to another. I found another picture of Skountris in a Greek website (click here). In this illustration, he is shown mounted:

When I took the picture of his monument back in 1977, I did so because I was attracted by the naivety of its sculptural style. At the time, I doubt that I even noticed the inscription below the bust. I only spotted it 37 years later! Now that I have seen photographs of Skountris, I realise that far from being naive, this sculpture is a very realistic representation of its subject.

What intrigues me is that this little monument in a tiny Greek village encapsulates the problems that have plagued the Balkan peninsula. Trigono was once just a small place in the large Ottoman Empire. Then, as this empire began to disintegrate at the end of the 19th century, it like so many other places began to be contested by the nations that evolved from the smouldering embers of the empire. Skountris is remembered because he helped to wrest the area from the rival Bulgarians. But, others in neighbouring states may still be looking hungrily at the area around Trigono and the Prespa lakes, where the borders of three countries now meet. Let us hope that whatever the aspirations of those who feel that the borders have been incorrectly drawn, peace will continue to reign in the area.

This article has been written by

Adam Yamey, who has published two books about the Balkans:

"Albania on my Mind"

&;

"Scrabble with Slivovitz"

Details of these books may be found by clicking

HERE!

Published on April 19, 2014 01:45

March 22, 2014

A FRIEND REMEMBERED

Shoreditch Town Hall, 21 March 2014

Sometime in March 1965, when I was almost 13, I attended a birthday party held by my school friend Hugh Watkins. After attending a showing of the latest James Bond film Goldfingerat our local Odeon cinema in Temple Fortune in northwest London, we had afternoon tea at Hugh’s home. It was at that tea party that I first met the brothers Francis and Michael Jacobs. They lived next door to Hugh. Michael, who shared his birthday with my mother, 15th of October, was a few months younger than me. It is curious that his mother shares the same birthday, 8th of May, with me.

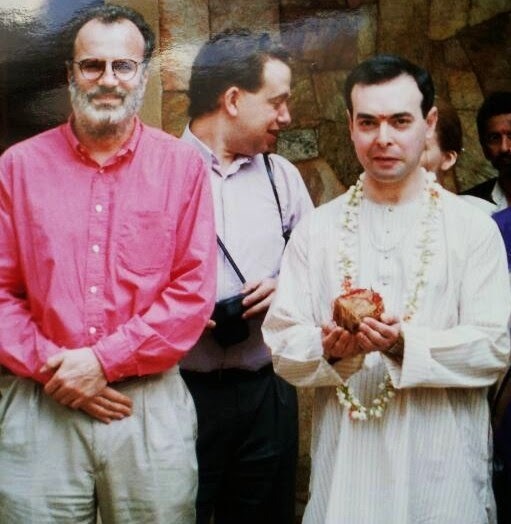

Michael Jacobs (in pink shirt) with Adam Yamey (in white robes and holding a coconut) in India, 1994

Yesterday, 21st of March 2014, I attended a large gathering to celebrate the tragically short life of Michael Jacobs. This moving occasion was beautifully organised by his wife Jackie along with his good friend Erica Davies. His death on the 11thJanuary 2014 came as a complete shock and surprise to me as I had not known of his illness. A number of people who had known him for varying numbers of years shared their memories of this remarkable person at the gathering yesterday. In this essay, I wish to share some of mine, a few of which derive from an era before which some of yesterday’s speakers knew him.

Michael was very musical. During his school years, he became an accomplished clarinettist. He told me that whenever he went on holiday, he had to carry a mouthpiece with him so as not to lose his lips' embrasure. His grandmother Sophie was friendly with John Beckett (1927-2007), a close relative of the writer Samuel Beckett. John was one of the people who began to re-introduce early music, and its ‘authentic’ performance into the concert repertoire. Sophie gave Michael and Francis a number of records that his ensemble Musica Riservata had recorded. We loved listening to these on the Jacob’s gramophone, and Michael learnt how to sing some of the renaissance songs. His renderings of these were superb, and continued to bring joy to his friends during the rest of his life. One of these, which he sang often, was called El Grillo.

During his later years at Westminster school, both Michael and I developed an interest in the Gothic and neo-Gothic eras. We were both interested, for example, in the novels of Walpole and Beckford. He carried this further by organising a ‘Gothic’ event at Westminster School. I was invited to attend this curious occasion, of which I recall little except that Michael had persuaded a number of his school mates to dress up in monk’s habits and wander around the cloisters whilst ‘Gothic’ music from his and also my collection of early music LPs was played over loudspeakers. The school authorities must have thought highly of him to allow him to put on this extraordinary event.

Michael enrolled at the prestigious Courtauld Institute of Art in about 1971. Very soon, he became recognised as one of the Institute’s better students. This caused him to be selected to join a group of academics on the Institute’s highly exclusive annual overseas excursion. He had to join the tour somewhere, which I cannot recall, in Europe. It might have been Bavaria. He asked me whether I would like to join him on a trip through the Low Countries and West Germany on his way to wherever it was that he was joining the art historical elite. I was on my university vacation, and it sounded like a good idea. We decided to camp to save money. I provided the tent, and we set off from Londonto Dover, where we crossed the English Channel.

I was carrying a rucksack with my belongings and the tent. Michael’s baggage was heavy and unwieldy. He was carrying not only the clothes and the sleeping bag that he needed for our camping trip but also things that he needed for his forthcoming trip with the academics. As this was to be a smart affair with formal dinners, he had to carry a dinner jacket and its accompaniments including smart shirts, shoes, and ties. He also lugged an enormous bag filled with huge hard-backed art books that he felt that he might need for that event. We camped somewhere near Lille in northern France on the first night. All went well until the following night, which we spent at Grimbergen just outside Brussels. We awoke the next morning to discover that the rain was falling heavily. Our tent was soaked, as were our sleeping bags. The rain managed to get into our baggage. Michael’s books got wet, and his formal clothes became dishevelled. We decided not to continue with camping, but instead to spend the rest of our trip sleeping in youth hostels.

Michael guided us to fascinating museums on our trip. He was somewhat short-sighted, and often went up close to paintings in order to - as he explained to me - examine artists’ brush-strokes. This often caused the men and women guarding the works of art to become anxious. They had nothing to fear from this young man, who was destined to become a significant art historian and a well-known writer.

When we reached the West German city of Marburg, I told Michael that I had run out of money. The £60 or so that I had budgeted had almost been spent. There was just enough to pay for my railway ticket back to London. On my way back, I had to spend the night in Liége. With nothing in my pocket except my ticket, I slept on a bench in the railway station. Michael continued on his way to meet up with the Courtauld party. Despite having had to cut it short, I enjoyed the journey and Michael introduced me to a lot of art which was unfamiliar to me. For example, had we not visited the art gallery in Dortmund, it might have been many years before I might have finally, if ever, learnt of the existence of the Blaue ReiterGroup and the marvellous expressionist paintings produced by its members.

Some years later in 1982 when I qualified as a dental surgeon, I learnt to drive and acquired a car. Michael, who never learnt to drive a car, was grateful to his many friends who were happy to enjoy his company and drive him around. I was one of them.

In 1984, Michael along with Paul Stirton published The Traveller’s Guide to Art: Great Britain & Ireland. The research for this involved a great deal of travelling around the British Isles. One holiday, I drove Michael along the south coast of Englandand around Walesso that he could visit museums and galleries in these parts. I had a cassette player in the car, and played many of the tapes that I had recorded from my large collection of Central European and Balkan music LPs. Michael enjoyed the exotic music, and once remarked to me that listening to it whilst travelling through the British countryside, made the somewhat familiar landscape seem a little less familiar, even a bit foreign and hence more interesting.

We began our journey along the south coast at Eastbourne. We arrived there in the late afternoon. Michael was dismayed to find that its art gallery was already closed. He suggested that we walk up to the building, and then try to peer in through its windows. This was unsuccessful; we could not see much inside it. Undaunted, he approached two young lads walking in the street close by. He began asking them whether they had ever visited the gallery. I thought that he was being a little over optimistic; the lads were skin-heads. And, in those days they were the least likely people to have been interested in art, and were potentially violent. Fortunately, we escaped unscathed.

During that trip, we celebrated Michael’s birthday by staying at a better than average bed and breakfast (‘B&B’) near to Newport in South Wales. He had chosen a beautiful place to stay. The breakfast that we were served was one of the best that I have ever eaten in a B&B. Apart from being offered a selection of different kinds of teas we were served perfectly prepared fish as well as the usual English breakfast items.

After visiting fine art galleries in Cardiff, Swansea, and Llanelli, we made a detour to Laugharne, where the writer Dylan Thomas lived and worked. It was a lovely spot.

The west coast of Waleswas devoid of places that were deemed suitable for his forthcoming book, but we drove along it one Sunday. We stopped for the night at an isolated village at the western end of the Lleyn Peninsula. The sole place to stay in this Welsh speaking village, which resembled the Scottish village that starred in the 1984 film Local Hero, was the place’s only pub. The village was teetotal on Sundays. So, we sat in the deserted bar eating an unsatisfactory evening meal without being able to wash it down with something alcoholic. As we were eating we could hear the thudding of loud pop music coming from somewhere in the building, but we thought nothing of it. After dinner, we decided to go for a late night stroll; Michael was a keen walker with an abundance of energy. When we left the bar and entered the lobby, some doors burst open, and a couple of young girls burst out. Seeing us, they asked us (in English rather than in their usual Welsh) whether we would like to join their party. We followed them into a room where a party was in full swing. There, we were offered beer and other alcoholic drinks; and were made to feel most welcome.

Llandudno, which we visited on the next day, had the most curious museum on our trip. It housed a collection of carved wooden Love Spoons. I can not remember whether Michael and Paul included this in their book eventually.

Throughout the trip, and others that I made with Michael, he was supposed to be our navigator. This was a good arrangement. He was a good map reader. The only problem was that Michael had a tendency to fall asleep in moving vehicles. Whilst investigating the art treasures of southern England, he was asleep as usual when we speeded through Cheltenhamand had continued beyond it. Suddenly, he woke and asked me where we were. I told him that we were almost at Gloucester. Somewhat panicked, he charmingly persuaded me that we should turn around and head back to Cheltenham which we had overshot by almost 10 miles. He had forgotten to tell me that it was supposed to be one of his stopping places before he had drifted off.

In 1986, Michael published another book, The Good and Simple Life. This book about the artist colonies of Europeat the end of the 19th century also required several chauffeurs during its research phase. I drove him to the West Country so that he could carry out field research in the Cornish towns of Newlyn and St Ives. We stayed in Newlyn, where he was allowed to bring the hand-written diaries of the artist Stanhope Forbes (1857-1947) from a local library to our bedroom in the B&B. He read them during the night, and the next morning we sat together for breakfast. We were the only two guests in the B&B, and we were confronted with a vast spread of greasy fried breakfast fare. I ate a little of it. Michael ate his share. Then, he looked at what was left on the table - a substantial amount of food - and said that we would have to finish it. I told him not to be ridiculous, but he replied that he did not want to hurt our landlady’s feelings by leaving it. He was genuinely concerned not to upset her. So, he finished it off. During the rest of the day, he kept clutching his stomach; his kind-heartedness and thoughtfulness for others was making him suffer.

I have to thank Michael for introducing me to St Ives. I have visited this beautiful little port many times since. Apart from visiting the Barbara Hepworth Museumthere, Michael and I also visited places associated with the artists who worked together in the town’s artist colony. This involved visiting the St Ives Art Club which was founded in 1890 and the archives of the town’s library.

At some stage during this trip, we stopped, and spent the night at, at Worth Matravers near to Corfe Castleon the Isle of Purbeck. He took me to a pub where the artist Augustus John (1868-1961) used to drink. When we entered, Michael asked the barman whether there were any traces of this artist in the pub, maybe some graffiti or something scratched into the woodwork of the bar. The barman, whose cultural knowledge was a microscopic fraction of Michael’s, looked at him blankly and said nothing. So, we ordered a pint or two, just as the great artist would have done many years before our arrival.

At yesterday’s memorial event, the renowned cookery writer Claudia Roden praised Michael’s culinary skills. This praise was well-deserved. Long before Roden sampled his cooking, I had been fortunate to have enjoyed many dishes prepared by him in the kitchen that he had constructed with his own hands in his home in Hackney. His mother was an excellent cook, but he surpassed her by being both excellent and also successfully ambitious. Few people could prepare a coulibiak (кулебя́ка) - in essence, a pastry filled with fish - as delicately as he did for me on at least 2 occasions.

His food was worth waiting for, and indeed one had to do just that. He would generously invite guests for dinner, but would arrive full of apologies long after them. The dishes that he would prepare for us as we sipped aperitifs never disappointed; and that was not just because we had all becomes so hungry waiting for them. As a cook, he was a genius. However, occasionally he was a little over ambitious.

This was the case when he decided to make home-made fresh pasta for a large number of people who were going to celebrate his 40th birthday at his home. He had decided to make enough fresh tagliatelle for at least 30 people. I arrived early at his house, and found him in the kitchen cranking his hand operated pasta machine. Layer after layer of strips of tagliatelle were accumulating on his kitchen table. To his dismay, he realised that they were beginning to stick to each other. I suggested to him that fresh pasta needed to be hung up to dry a bit. So, we separated the ribbons of pasta and hung them over the backs of the assortment of wooden chairs in his kitchen and anywhere else that seemed suitable. When that was complete, he had to face the problem of cooking this vast amount of pasta, and then serve it with his home-made ragu.

On another occasion, my wife and I turned up at his home the day after he had had a dinner party, at which he had served his home-made filled pasta. Not only had he made the pasta himself, but also the delicious filling. The few leftovers that he cooked for us matched the best tortellini that we hade ever eaten anywhere - and my wife had lived in Italyfor 4 years.

Michael was blessed with a great sense of humour. He was very witty. When his brother got married in Ireland, I drove Michael and Jackie to Avoca in Eire, where the wedding was being held. At the reception after the ceremony, Michael began his best man’s speech by saying something like: “Unaccustomed as I am to speaking in public…” then pausing for a few seconds before continuing, “… without being paid.” This had everyone present roaring with laughter. A few moments later, he continued: “I had originally thought of projecting a few slides showing Francis’s development from infancy to adulthood, but then I decided against it. After all, this is a family show…”

Michael’s death has left a gap in many people’s lives. As the memorial event at Shoreditch Town Halldemonstrated so vividly, he meant many different things to many people. But all of us, who attended the event, were united in at least one thing: we all felt his great affection for us. Overall, he was one of the most life-enhancing people I have ever met.

Michael Jacobs with Lopa and Adam Yamey at their wedding reception in Bangalore, 1994

I feel privileged to have been his friend and that he was one of the few people who made the long journey from Europe to India in order to celebrate my marriage to Lopa in Bangalore.

+ + + + +

Read about Adam Yamey's writing on:

http://www.adamyamey.com

Published on March 22, 2014 09:22

March 9, 2014

ALBANIANS IN VENICE

Statue of Skanderbeg near Bayswater in London

(http://londonpostcodewalks.wordpress....)

Between 1385 - when the Turks beat the Albanians at the Battle of Savra near modern day Lushnjë - and 1912, Albaniawas part of the Ottoman Empire. The Albanians did not take their defeat sitting down. They offered much resistance, the best example being that offered in the 15th century by the Albanian hero Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu (1405-1468), better known to English speakers as ‘Skanderbeg’. Despite the brave attempts of the Albanians to rid themselves of the Turks, Ottoman rule was established firmly. Many Albanians fled the country and started new lives abroad, often in places that are now part of modern Italy.This excerpt from a work in progress by Adam Yamey reveals his up until now brief experience of the Albanian community that fled from the Ottomans invading their country to Italy. The illustrations are all harvested from the Internet with one excep[tion, and their sources are given, as well as gratitude to those who posted them.

Skanderbeg's stronghold at Kruja in Albania (1984)

(Author's photograph)

Excerpt from a work in progress by Adam Yamey:

“The small Bar Redentore was just across the AcademiaBridge that straddles the Grand Canal. I am not sure why my parents favoured this amongst all of the many bars in the city, but they did. They drank good quality espresso coffees whilst we children enjoyed munching tasty tosti. These are toasted sandwiches often containing prosciutto crudo and slices of cheese. The Italians make these better than almost anyone else. The sandwiches are not squashed in a heavy grill but instead are gently suspended between the heating elements of a toaster. The result is a much lighter tasting sandwich than those prepared in the heavier grill that compresses them as it cooks. We never sat down in Italian bars, be it in Veniceor elsewhere. Even if the bar man offered to seat us, my mother refused. She knew that there was a hefty surcharge for sitting down in a bar or café.

More than 35 years after my last visit to Venicewith my parents, we visited the city with our then 10 year old daughter, who had seen pictures of the place in a magazine and was longing to visit it. Prior to arranging the visit, she was learning how to swim. We told her that once she had learnt, we would take her to Venice. This inducement worked, and we re-visited the holiday place of my childhood. During the visit I was surprised to discover that many of the shops and other businesses that we had visited in the ‘60s and ‘70s were still operating in 2005. These included a small shop selling decorative paper items made in Florence as well as the Bar Redentore, where we also stopped for a drink.

We used to reach the Redentore by walking across the Campo San Stefano, where we sometimes sat down during the afternoon, and then passing along a narrow alley, which contained a building that has long intrigued me. It was the Scuola degli Albanese. This building whose façade, which is almost impossible to photograph properly on account of the narrowness of the alley, is covered with carved stone bas-reliefs.

The facade of the Scuola degli Albanese in Venice

(http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scuola_d...)

By the time that I had reached my early teens, I had developed a great interest in the then very mysterious country of Albania. Anything connected with that place, which was then almost inaccessible to anyone from the world around it, was of great fascination to me. We used to stop and look at this building, wondering what it had to do about Albania, but I never found out … until recently.

Detail of facade of Scuola degli Albanese in Venice - a Turk contemplating the Fortress of Shkodër in Albania

(http://www.flickr.com/photos/hen-mago...)

In February 2014, I was attending a reception at the Albanian Embassy in London when I met the great scholar of Albanian matters, Bejtullah Destani. This highly approachable friendly man began talking to me. As we chatted, I suddenly remembered the Scuola degli Albanese and asked him about it. If anyone knew anything about it, it had to be him. And, I was right, but I was not prepared for his reaction. He looked surprised that I knew of its existence. He said that he believed that of the 40 or so people assembled at the reception, many of them Albanian and the others having a great interest in Albania, I was probably the only person there who had ever heard of, or even noticed, this building.

Destani told me that when the Turks invaded Albania in the 15thcentury, many Albanians fled the country. Some went to southern Italy and others to Venice. He explained that the Scuola degli Albanese was the headquarters of the Albanian confraternity in Venice. The Albanian community in Venice was extremely prosperous, and well able to hire the fashionable painter Vittorio Carpaccio to paint a series of canvases to decorate the main hall of the Scuola between 1504 and 1508. These paintings, which still exist, are no longer in the building, which has long since ceased to serve its original function; they are scattered amongst museums all over Italy. This contrasts with the set of Carpaccio’s paintings that are still in situ in the Scuola degli Schiavoni not far from St Mark’s Square. We used to visit those beautiful pictures lining the walls of a dimly lit room almost every time we visited Venice.

One of the pictures by Carpaccio that used to hang in the Scuola degli Albanese: nowin a museum in Bergamo.

(http://mescarnetsvenitiens.blogspot.c...)

Mr Destani also told me that when the Scuola degli Albanesi ceased to function as a confraternity, the entire records of the Albanian community in Venice, spanning several centuries, were transferred to the Archives of the City of Venice, where they are awaiting scholarly examination.

Santa Maria del Giglio in Venice

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Santa_Ma...)

Close to the Scuola degli Albanese, but nearer to St Marks Square, there was a church that interested me because of my interest in the Balkans. It was Santa Maria del Giglio (known by the Venetians as 'Santa Maria Zobenigo'). At the base of its florid neo-classical façade there were a number of maps carved in bas-relief. At least two of these were of places on the Dalmatian coast, namely Split and Zadar (or 'Zara', in Italian). There was another one depicting ‘Candia’, now known as Heraklion on Crete. These maps interested me. The rest of the façade interested my parents.

Map of Zara (Zadar) on facade of S. Maria del Giglio in Venice

(http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fil...)

_____________________________________________

See also:

http://mescarnetsvenitiens.blogspot.co.uk/2010/04/scuola-di-santa-maria-e-san-gallo-degli.htmlhttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scuola_degli_Albanesihttp://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storie_della_Vergine_(Carpaccio)

Adam Yamey visited Albania in 1984. His memories of this

extraordinary journey are published in his book/ e-book

"ALBANIA ON MY MIND"

This is available from Amazon, Barnes&Noble, and Bookdepository, and also www.lulu.com

Published on March 09, 2014 04:04

February 11, 2014

A MOST COSTLY RAILWAY

Retired railway locomotive in Barkly East, 2003

I never met my mother's father, Iwan Bloch, as he died many years before I was born. His eldest son, my late uncle Felix, remembers sitting with him when he returned home from work and opened his correspondence. This was in the 1920s when Germany, where Iwan's family came from and where many of them still lived, was undergoing a severe hyperinflation. Felix remembers that many of the stamps stuck on envelopes from Germany bore high denominations, many thousands or hundreds of thousand, or maybe even millions, Deutschmark.

My late mother remembers taking the train from Barkly East to Aliwal North on her way to boarding school in King Williams Town. The first part of the journey was mountainous. The train had to negotiate a series of switchbacks, and moved very slowly. She remembers that her elder brother Felix and many of the outher young boys on the train, used to jump out of it and run down the slope to the next lower stretch of railway. There, they would wait for the train to make its way down to where they were sitting by the track. This railway would probably never have existed had it not beeen for my Grandfather Iwan Bloch...

At 11 p.m. on the 8thApril 1886, a birth was recorded in the town of Diessenhofen on the Swiss side of the Rhine. The child was my grandfather Iwan Isaak Bloch. He was of German nationality as his father Salomon Bloch was born in the town facing Diessenhofen on the German side of the Rhine, Gailingen in the state of Baden. Salomon had a store there. Iwan's mother was Peppi Bloch, née Seligmann. She was one of the fifteen surviving children of Isak Rafael Seligmann of Ichenhausen in Bavaria. Iwan died in 1931 in Johannesburg, having been a successful businessman and also the Mayor of a small town in the Eastern Cape, Barkly East. This is his story.

Wedding day of Iwan Bloch and Ilse Ginsberg

Before we continue with Iwan, it is necessary to describe the events that led to his arrival in South Africa. The Mosenthals of Kassel were probably the first German Jews to have made a success of trading in South Africa. Around and shortly after 1839 Joseph Mosenthal and his brother Adolph settled in Cape Town and became general merchants. They were very successful and set up trading posts in the interior of the Cape Colony and beyond the Orange River (Saron & Hotz pp 349-55). The importance of the Mosenthals in establishing an efficient system of commerce throughout the Cape and beyond cannot be over emphasized. To quote Saron and Hotz (p. 350) they, "not only acted as intermediaries who bought and sold; they were also, by force of circumstances, the financiers and bankers of that first generation in which their business took root". Further on, Saron and Hotz write (p 353), "Firms like Mosenthals were responsible for attracting to South Africa, as assistants, many good class immigrants who were able to give services otherwise almost impossible to supply in the comparatively undeveloped state of commerce and finance. These men in turn contributed towards the further extension of trade and industry in their new homes." These homes were the small towns scattered all over the Cape Colony and along the Orange River. Iwan Bloch's uncle Sigmund Seligmann (Iwan's mother's brother) was one of these men attracted to South Africa. Louis Herrman (p. 216) noted that, "The Mosenthals and their industrial and commercial activities were the means of introducing into South Africa nearly half the Jewish families who came to this land between 1845 and 1870".

Sigmund Seligmann

The Seligmann family of Ichenhausen in Bavaria was quite enormous. Some of the family were involved in commerce in Ichenhausen during the nineteenth century. Many of them emigrated. Sigmund Seligmann had a first cousin Heinrich Bergmann who arrived in South Africa in 1849. He was a very successful member of the Mosenthal business, and by the time of his death in 1866 was running their branch (under the name of "Mosenthal and Bergman") and their bank (the Frontier Bank) in Aliwal North. I have written about Bergmann in a recently published article (see Stammbaum, issue 25, 2004). I suspect that Bergmann was one of the earliest members of the extended Seligmann family to reach South Africa. Sigmund Seligmann came to South Africa in 1874, aged 18 years (having already spent two years in the USA!). He worked in businesses in Rouxville and in Lady Grey before setting up his own trading business. His first business was started in partnership with Moss Vallentine in Dordrecht, Cape Colony, in 1884. This did well. In 1885 Sigmund decided to open another store, in Barkly East, on the Langkloof River, north of Dordrecht in the southern edge of the Drakensberg range of mountains. It is one of the highest towns in the Cape. The opening of S.Seligmann and Co. Ltd, took place in 1886. Gradually Sigmund sent for three of his nephews: Jakob Krämer, Julius Cornelius and Moritz Rosenberger (incidentally, he also was a member of the brass band of Barkly East). They came out from Germany and helped to run the business before and after Sigmund returned to Germany in 1898. Other nephews were sent out to help in the business and amongst these were Iwan Bloch and his brother Daniel.

The Seligmann store occupied the site where Lewis &the Barkly East Bottle Store stand. It was burnt down in the 1960s.The red roofed building beyond it was a store for wool bought by Seligmann's.

Now I shall digress to describe the Jewish life of Barkly East, of which there is little to report. Barkly East was mainly a commercial centre for the flourishing local sheep farmers and the wool business. Its heyday antedated the building of good motor roads. In latter years when road transport became better (after WW2) its importance declined as the farmers were able to reach bigger centres such as Queenstown and East London. Saron and Hotz make one mention of Barkly East: a Jewish cemetery was consecrated there in 1894. The earliest gravestone in the cemetery records the death of Hannah (wife of Manassah) Woolf who died in February 1894. In an appendix I have provided a list of the Jews who were buried in Barkly East, with some notes about their families. I do not know when the first Jew(s) arrived in the town, but Iwan Bloch's uncle Sigmund Seligmann was certainly there by 1885. Barkly East had no synagogue and was probably not visited much by rabbis from neighbouring towns. The last Jewish family to live in Barkly East was that of Lazer Bortz. Lazer and his family were of Russian origin. They joined Seligmann's on arrival in the town. Later they started their own business, a dealership in fuel. They left the town some years ago, in the 1980s (approx.) and were last heard of in Bloemfontein. Of all the Jewish businesses, the only one that retains its name today in Barkly East is that of Bortz, albeit under new ownership. Whilst we were visiting Barkly East last year, a curator in the town's small museum showed us a small object which she had detached from the deserted and derelict former home of the Bortz family. She asked us to identify it as she was unaware of its significance: it was the Mesusah, with its scriptural contents intact, from the family's front door!

The branch of Seligmann's at Moshesh's Ford, 2003

Before going out to South Africa, Iwan Bloch left Gailingen and lived in Zurich where he was employed in a department store. Clearly Iwan was a good choice as a helper in his uncle's store as he had already had some experience in commerce. According to information on his Certificate of Naturalization (April 1908), Iwan arrived in South Africa in 1903, aged 17 years, landing at East London (where he stayed for 6 days at Deals Hotel) in 1903. Then he went to Barkly East where he became a "general dealer's assistant" at S.Seligmann & Co. When Iwan arrived, the firm was directed by his three cousins: Krämer, Cornelius and Rosenberger. Seligmann's was not only a general dealer (they sold everything from cups to coffins, from pins to farm equipment. My late mother recalled that the firm imported the latest clothes from the leading fashion houses of Paris. Seligmann's was the 'Harrods' or 'Saks Fith Avenue' of Barkly East!). It was also involved in issuing credit to farmers and handling the wool produced by the many sheep farmers in the area. When the farmers were hard up, Seligmann's sold to them on credit, and when the wool was harvested the farmers settled their debts. Iwan worked his way up through the firm from clerk to a managing director, in conjunction with his friend and neighbour Carl Blume.

According to Iwan's obituary (in the Barkly East Reporter), "The late Mr. Bloch was born in Germany, and who was 45 years of age, came here in 1903 when he was a mere youth. He joined the firm of Messrs. S Seligmann & Co, and soon showed that he possessed a remarkable business attitude. Within a few years he and Mr. Blume had taken over the business, Mr. Bloch acting as managing director, a position he filled with great success." I am not sure exactly when Iwan became a managing director of Seligmann's, but it was most probably before 1916, when Iwan married Ilse, daughter of Senator Franz Joseph Ginsberg of King Williams Town, a signatory of South Africa's Act of Union in 1910. Her mother was Iwan Bloch's second cousin, Hedwig, née Rieser. Franz Ginsberg was not merely an important public figure in the Eastern Cape, but was also a major industrialist in the area. He was an important South African manufacturer of soap, candles and matches.

Iwan's business achievements alone would have qualified him as a success in life, but this was not enough for such a hardworking and intelligent person as he was. Returning to his obituary, " But immersed in business as he was, he found time to take his share in public life here. For twelve years he was member of the Municipal Council, and for eight years in succession he was Mayor, until he retired in September last. It is not too much to say that we never had a better Mayor, and that his term of office was marked by great progress in Municipal matters.The electric light was installed; the accommodation for Natives in the Location was twice added to; and the town greatly benefited from his knowledge of finance and his business acumen. He was ever to the forefront in the advocacy and carrying out a progressive policy, and his actions were always designed with a view to furthering the best interests of the town as a whole." Iwan was a member of the Barkly East Municipal Council from 6thMay 1919 until 21stAug 1931, a few months before his death. He was, I believe, the first Jewish member of the Council, and most probably the town's only Jewish Mayor (his term of office was 4thSep 1923 until 21stAug 1931). Even before becoming a member of the Council, Iwan appears to have been interested in public works. I have a photograph of him in 1918 standing with several of the town's officials at the opening of a dam built to improve the town's water supply. He was also Chairman of the town's Chamber of Commerce.

Iwan Bloch's home as it was in 2003

Iwan's impact on the development of Barkly East was not inconsiderable. In 1910 the town's Council had made enquiries into the possibility of acquiring an electricity generator to provide lighting for the Town Hall and the main square, but nothing came of it. Under Iwan's Mayoralty, in 1927, the electrification of Barkly East was finally achieved. Electricity was available for the use of inhabitants between the hours of 4 PM and 12 PM only! By 1930 Iwan Bloch warned the Council that the existing electricity scheme no longer met the needs of the town, and three years after his death this was remedied. Iwan's greatest municipal achievement was his involvement in bringing the railway to the town.

In about 1902 the burghers of Barkly East began to campaign to have a railway built to the town. A connection to Aliwal North would have joined Barkly East to the existing rail network of South Africa, and no doubt would have worked wonders for the prosperity of the town. A Railway Committee was established in October 1902. By November 1905 a railway had been built from Aliwal to Lady Grey, and was a success financially once it became functional. This fuelled optimism in Barkly East. By 1916 the railway had reached New England, 18 miles from Barkly East. Much campaigning for the railway occurred between 1916 and 1924 when the Railway Board of South Africa finally visited Barkly East in connection with extending the railway to the town. By the following year, Iwan Bloch had already become the Chairman of the town's Railway Committee. He received the news that the government had finally agreed to build the long awaited extension of the railway to Barkly East. Despite this there was procrastination on the part of the government, and the construction of the railway was delayed: there was a shortage of funds. It was not until May 1928 that Iwan Bloch received the following telegram from Mr. Sephton, a Member of the Legislative Assembly, "£40,000 provided for the construction of New England/Barkly East Railway".

The remains of the switchbacks on the railway just outside Barkly East, 2003

Exactly a year and two days before Iwan's death, the official opening of the railway to Barkly East was celebrated on 10thDec 1930. Two days later the Barkly East Reporter wrote, "As the train headed for the station, it was seen to consist of an engine and three of(sic) four coaches. The engine, which was decorated, had a very festive appearance. As it passed under the arch and entered the station, the Mayoress, Mrs. I.I. Bloch, performed the ceremony of christening it, by dashing a bottle of champagne…. against it". The town celebrated the arrival of the railway with a day of events including a Fancy Dress Carnival in which cars were decorated in imaginative ways. I note with some pride that the car decorated by Seligmann's won second prize in the Best Decorated Car competition. In a fancy dress parade Iwan's brother Daniel and his wife appeared as a Swiss Couple. Amongst the children in fancy dress is mention of Master Iwan Bloch, one of my two uncles, dressed up as 'Red Riding Hood'. It is of interest to note that the extension of the railway from Lady Grey to Barkly East was, according to the South and East African Handbook and Guide (1947), "….one of the most costly (about (£8,000 per mile) in South Africa owing to the mountainous nature of the terrain", and is today sadly non-functional.

How Iwan found time for leisure is a puzzle, yet he did! Barkly East was (in the Twenties and Thirties) a hive of social activity, difficult to imagine today. Iwan participated in tennis parties, held more than once a week. There was time for playing bridge, and a daily walk, not to mention many other social gatherings including golf twice a week. The family owned a number of motor cars (the most expensive newest imported models of the time) including a Hupmobile, which was used to transport the large family (Iwan had four children) on holidays to a wide range of destinations all over South Africa. My mother recalled that she and her siblings were often car-sick, and on occasion Iwan's hat acted as a receptacle for one of the symptoms of this! Iwan and his wife also made occasional trips to Europe to see family members in Germany.

In the second half of 1931, Iwan suffered a massive heart attack. He was transported to Johannesburg for medical treatment. He spent his last weeks in a nursing home (? Fairview) in Johannesburg. He passed away on the 12thDec 1931, and was buried in Johannesburg. His obituary noted that he was, "Of a kindly and sympathetic nature(and that)he will be sadly missed by a large circle of friends and by the poor alike". Although the Bloch family was not observant in religious matters it is worth noting that Iwan was buried in a Jewish cemetery, and the ceremony was officiated by a Rabbi.

He left behind him a widow and four children including my mother. His widow remarried Oscar Levy, who also worked for Seligmann's. Tragically, he died shortly after their marriage and the birth of their son. Oscar is buried in Barkly East. Seligmann's, the business continued to exist until the early 1960s, watched over by a member of the Bloch family and by the Ginsberg's in King Williams Town. A large fire in about 1965 destroyed the main building of Seligmann's. Today all that remains in Barkly East is the Bloch's former home and some of the many smaller buildings that belonged to the firm.

The railway to Barkly East no longer functions. When we visited it in 2003, we were told that traind had run on it occasionally, but since a fatal accident on one of its infrequent runs it no longer operates. However, this video made in 2001 will help you to relive the glory of the railway that my grandfather helped to create. Click on this image to see it:

Appendix: Jewish Graves in the Cemetery at Barkly East

View from Barkly East's cemetery towards an African settlement, 2003

When we visited Barkly East in August 2003 we visited the small museum there. We met the curator who very kindly provided me with a list of the Jewish graves in the cemetery. The Jewish cemetery is within Barkly East's 'white' Christian cemetery on the edge of the town on the road leading to Moshesh's Ford and Rhodes, two places at which Seligmann's had branch stores. The Jewish section is small and separated from the rest of the cemetery by a metal fence. The whole place is subject to vandalism and I suspect that in a few years time most of the graves will be unrecognizable. My list gives 11 graves: last years only 6 of these were identifiable - the rest were damaged too much to be recognised.

The listing is as follows;

Isaac ROSENBERG: London, d. 26 Apr 1956, aged 56 yrs.[Dr. Isaac Rosenberg, born in Barkly East, was a highly respected and much loved medical doctor in Barkly East.]

Emil SELIGMAN: b. 3 June 1877, d. 25 Aug. 1897[Emil Seligman(n) was born in Ichenhausen in Bavaria, and ran the branch of Seligmann's in Rhodes. He was a cousin of Iwan Bloch]

Bluma Chaia ROSENBERG: d. 30 Jul 1921, aged 52 yrs. (wife of Morris Rosenberg)[Mother of Isaac]

Nathan LEVENSON: d. 12 Jan 1927, aged 32 yrs.

Jack VALLENTINE : died 7 Mar 1897, aged 32 yrs. (son of Phillip)[Jack Vallentine, from London, worked with Sigmund Seligmann. His brother Moss Vallentine was a partner with Seligmann in a business in Dordrecht, south of Barkly East. Jack was married to Helene Perlmutter, sister of Erna Perlmutter who was married to Sigmund Seligmann. Jack's untimely death was caused by tetanus, contracted as a result of falling from a carriage.]

Hannah WOOLFE: d. 10 Feb 1894 (Wife of Manassah Woolfe)

N. JOFFEE: d. 7 Oct 1917, aged 11 mos.

8. J. JOFFEE: d. 7 Oct 1917, aged 11 mos.

VAN DER HORST: d. 5 Sep 1932, stillborn.

S. EDELSTEIN: d. 17 Sep 1944[The Edelstein's owned a retail business in Barkly East]

Oscar LEVY: died 27 Sep 1934, aged 32 yrs.[Oscar, son of Judah Levy of Melsungen in Hesse in Germany, came out to work in Seligmann's, invited by Iwan Bloch. He was highly educated. He married Iwan's widow, but died soon after.]

EXPLORE MORE WRITING BY

ADAM YAMEY

INCLUDING 2 NOVELS

SET IN SOUTH AFRICA

CLICK HERE TO DISCOVER MORE!

Published on February 11, 2014 05:00

February 7, 2014

A GREAT ALBANIAN SINGER

Vaçe Zela, the great Albanian chanteuse died on 6th February 2014 in Basel (Switzerland)

Sadly, I never met her nor attended any of her concerts. However, recordings of her songs were my first encounter with music from Albania. This excerpt from my book Albania on my Mind tells how I 'discovered' the music of V. Zela in the mid to late 1960s:

"Ihad a Phillips radio in my bedroom. It was a valve radio, rather than the more modern transistor-based instruments, which were already available in the 1960s. Once it had warmed up - a slow business taking up to a minute - and had stopped emitting crackling sounds, it was able to receive broadcasts on three wavebands including short-wave. I used to enjoy twiddling its tuning knob, and listening to broadcasts transmitted from all over the world. It was a window to the world beyond the confines of the highly manicured, desirable but rather dull, Hampstead Garden Suburb, where we lived.

One day, I tuned in on an exceptionally clear transmission, and listened with some curiosity and a great amount of surprise to a woman who was speaking perfect English with only the hint of a foreign accent. After a few minutes, she informed her audience far and wide that they were listening to the voice of Radio Tirana. I could not believe my ears. I made a mark on the tuning gauge to ensure that I would be able to find this station again. I tuned into Radio Tirana regularly, listening with astonishment and also amusement at the various commentators’ beautifully articulated words - mostly rants and raves directed against the actions of the imperialists and capitalists. These were punctuated by stirring Albanian songs sung in a style that was new to me, as I had never experienced the music of the Balkans before. Incidentally, the clarity of the transmissions from Tirana was due to it being broadcast from a reputedly very powerful transmitter.

After a short while, I decided to write a letter to Radio Tirana. Somewhat tongue in cheek, I wrote to the unknown addressee (in English) that the songs, which were being broadcasted from Albania, inspired me greatly and helped to reinforce my faith in Socialism. After addressing the letter’s envelope to ‘Radio Tirana, Tirana, Albania’, I waited with little expectation of receiving any kind of reply. I thought that it was more likely that I would receive a communication from MI5 or MI6 than anything from Albania. However, I was wrong to have been so pessimistic. A flat parcel, wrapped in brown paper and string, arrived by post a few weeks later. It was from Albania. I unwrapped it carefully, my fingers thrilling at the thought of handling something that had arrived from the mysterious country that had begun to interest me so greatly.

The package contained a 10-inch diameter long-playing gramophone record in a garishly coloured cardboard sleeve. It was decorated with an electricity pylon; musicians in folk costumes; dancers dressed likewise; a man wearing baggy Turkish-style pantaloons; and an oil derrick. The plain, unadorned record label bore the name of the recording company: Pllake Shqipetare(‘Shqipëria’ being the Albanian word for Albania). I played this endlessly, much to the dismay of my parents who did not appreciate its special musical properties. Even today, I can still hear the tune of “O djell i ri” (a song about the sun) ringing in my head."

Click on the image below to hear this song:

And, the singer of that song and a few others on the disc was the late and much lamented V Zela. There was also a song sung by her called Fëmija i parë. For many long years I believed that that title meant 'Women are equal' but 3 days ago, I learnt that it actually means ' First born baby'. My informant was none other but the Albanian scholar, Bejtullah Destani. To hear this song sunng by V. Zela: click on this image:

Those of you who are interested in reading more of my experiences of Albania and the visit that I made there in 1984 may purchase a copy of my book, Albania on my Mind, (paperback and e-book) on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Bookdepository.

Published on February 07, 2014 03:10

January 31, 2014

HITLER WITHOUT THE HOLOCAUST?

I found this book about Hitler, which was published in 2007 (ISBN: 9788131002520) and is part of a series called “Biographies of Great Personalities” aimed at younger Indian readers, in Gangaram’s Bookshop in Bangalore (India). The garishly covered book caught my eye in a large bookshop in Bangalore(India). When I flicked through it, I noticed that it was illustrated with line drawings, many of which showed Adolf Hitler in Indian settings with palm trees. At 40 Rupees (less than half a Pound Sterling), I could not resist buying the 93 page book.

Young Adolf with his mother

The author, Igen B, is a prolific writer. He has published well over 70 short books including biographies of personalities as diverse as Jesus Christ, Bhagat Singh, Mother Teresa, Ashoka the Great, Chhatrapati Shivaji, Shakuntala, and Netaji Chandra Bose. As well as these he has written versions of great Indian classics such as the Vedas, the incarnations of Lord Vishnu, and the Mahabharata. That these books are probably aimed at children is evident from the format and appearance of the books and also the fact that one of his titles is “Illustrated Model Book of School Essay etc.” Therefore, his potential audience is the innocent and impressionable younger mind. This should be remembered whilst paging through his children’s biography of Adolf Hitler.

Hitler at his mother's death-bed

More than half of the text is dedicated to Hitler’s childhood, about which not much is known in detail, his career as an artist, and his rise to power. The author of this book, Igen B, blames a disturbed childhood in a dysfunctional family for much of what Hitler was to become. The future dictator’s disillusionment with the lack of German national pride and his disappointment with the country’s leadership during WW1 were according to this book, also important formative factors. As, are also the Jews: unquestioningly, Igen B repeats the kind of dangerous nonsense about the Jews that Hitler and many Germans believed.

Hitler discusses world problems and anti-Semitism at a café in Vienna

Having gained power, we learn of Hitler’s campaign to relieve the Jews of any role in public life, and his hatred of the communists. We also learn of his desire to tear up the Treaty of Versailles, and how he went about doing so. So far, the reader is presented with something that faintly resembles what is now common knowledge about the history of Germanyjust before and during the brief, but long enough, era of Nazi rule. The penultimate 4 pages of the book describe some aspects of WW2. The last page of text is dedicated the last days of Hitler and his new bride Eva Braun.

Hitler, the artist, at work on a painting

Nowhere in the book are the mass murders perpetrated by the Nazis even hinted at, let alone mentioned. This worries me greatly considering that the book is sold in bookshops in India, and most of these also sell often more than one edition of Hitler’s pernicious ‘autobiography’ “Mein Kampf”.

Adolf Hitler meets the common people (of Germany).

Igen B’s book is aimed at an Indian audience. It is appropriate in a way that the illustrations are drawn with an Indian flavour, as many readers are unlikely to have visited Europe or are ever likely to do so. The spelling of many German words and names is peculiar. For example we read of ‘Hebzburg’ (Habsburg), ‘Strum Abtiling’ (Sturmabteilung), ‘fonn’ (von), ‘Versai’ (Versailles), and ‘Hoffbraha’ (Hofbrauhaus). Whilst these original spellings are used more than once and are thus unlikely to be typographic errors, they may also be purposeful. It is possible that the author, realising that most of his readers are likely to be unfamiliar with German pronunciation, has transliterated them so as to make them pronounceable by readers of English.

Eva Braun comforts Hiler after he has learnt of the defeat of his armies by the Soviet Russians.

I picked up this book as a curio, and read it. The author appears to have done some research, but his or her interpretation and presentation of the facts is somewhat unusual. His lack of emphasis of Hitler’s evil influence and deed in a book aimed at impressionable youngsters is worrying to say the least. The impression I had after reading it was that Hitler was portrayed as an unfortunate child, who grew up with the aim of making Germanya great nation. I was not given the impression that he was even a fraction of the monster that he was in reality. I had rather the same impression after watching the end of the film Downfall made in 2004. Hitler’s final moments during that film were almost heart-rending; the power of film and literature cannot be underrated. This is why Igen B’s book on Hitler might well be considered malevolent, even if the author’s intention was otherwise, to be purely informative.

Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun on their wedding day.(Note the somewhat oriental background)

Read about the books written by the author of this blog by clicking on: http://www.adamyamey.com

Published on January 31, 2014 02:53

December 15, 2013

An artist in Albania

I have just finished reading Edith and I , a book written by Elizabeth Gowing. I have reviewed it on https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/733589531 . It is about the life of Miss Mary Edith Durham (1863-1944), and concentrates on her visits to the area of the Balkans that is now the Republic of Kosovo. Miss Durham is known affectionately by modern Albanians, whose cause she championed before and after the First World War, as Mbretëresha e Malësoreve (the 'Queen of the Mountains').

Until I read Gowing's book, and then looked up Durham on Wikipedia, I had not realised that Miss Durham had been trained as an artist and illustrator long before she embarked on her travels to the southern Balkans. Long ago, I acquired an early edition of Durham's book entitled High Albania. It is a brilliantly written account of her travels in the rugged mountains of northern Albania and neighbouring Kosovo and of the people whom she met there.

I took a fresh look at my copy of High Albania, and realised that its author was indeed a fine illustrator. The rest of this article is dedicated to presenting a few examples of Durham's hand-drawn illustrations in her book. Her attention to detail was marvellous, as was her ability to capture the 'atmosphere' of a place. Despite the presence of her own photographs in her book, it is the drawings that help to make it really special.

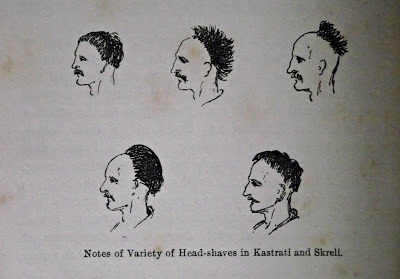

Of this picture, Miss Durham wrote, "To study head tufts one must go to church festivals. Only then are a number seen uncovered."

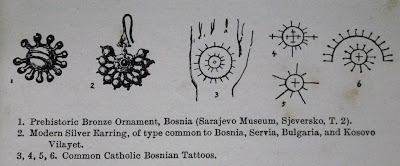

The two pictures shown above are of anthropological and/or ethnographic interest. It is not surprising to learn that Miss Durham's inherent ability to observe the characteristics of people and to report on them scientifically was recognised by the Royal Anthropological Institute (of Great Britain & Ireland) who appointed her a Fellow of it. The next 2 pictures illustrate Durham's skills in capturing both great detail and also the genreal 'atmosphere' of places that she visited.

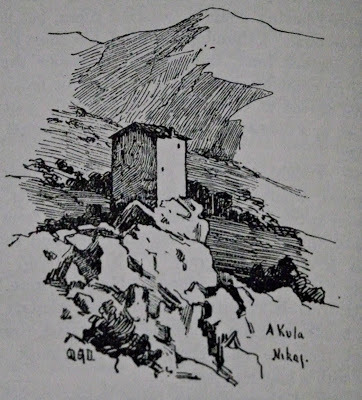

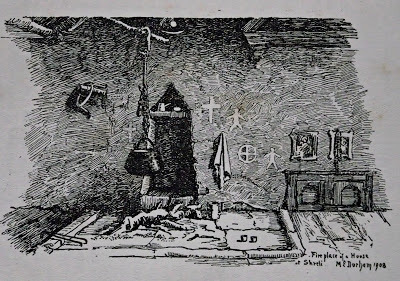

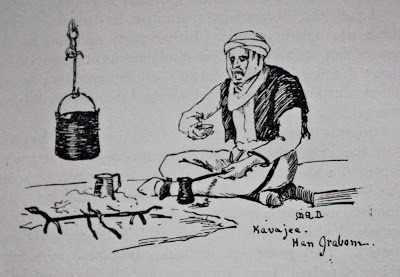

The first of these two shows the interior of a house in Skreli, in the northern highlands of Albania. The crosses drawn on the wall next to the hearth indicate that the house was home to some of the many Albanian Roman Catholics who lived in the area. The second of these, the kavajee or coffee-maker, shows him holding the jezva, in which Turkish-style coffee is brewed, in one hand and the cup into which it will be served in the other. The next picture shows Durham's skill in depicting architecture.

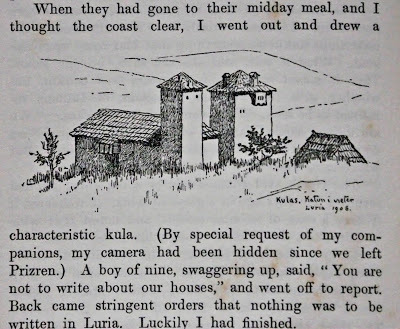

The drawing above, although very competent must have been drawn at speed, as the accompanying text, which I have copied, suggests. It shows a couple of kulle or fortified tower residences that are not only typical of the lands inhabited by Albanians but can also be found in the Mani Peninsular that projects from the southern Peloponnese (see my picture below).

As Gowing's book relates much about Durham' s visits to Kosovo, I have decided to include some of the pictures from High Albania that were drawn whilst Edith was there. Here is one showing a Serbian woman from Ipek carrying a cradle on her back:

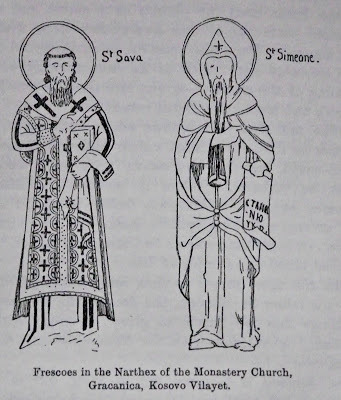

And, here is another one showing two of the fine frescoes inside the Serbian monastery at Gračanica ( Graçanicë), not far from the Kosovan capital as well as the site of the Battle of Kosovo Polje where the Serbs were narrowly defeated by the Ottoman army on the 15th June 1389.

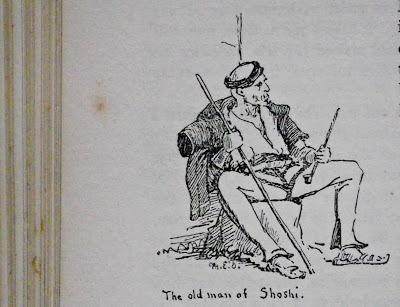

Today, visiting the monastery is not as simple as it was when I visited in 1990 (see my recently published book about Yugoslavia Scrabble with Slivovitz - click here ). When Elizabeth Gowing visited it, the Serbian monasteries in Kosovo had become like tiny rocks in a vast sea of Albanians. Surrounded by razor wire fences and guarded by heavily armed militia to protect these islets of Serbian culture from the Albanians, who rightly or wrongly lose little love for the Serbs, entry to them is subject to intensive identity checking and might be denied. The last of my examples of Durham's drawings brings us back to northern Albania, which is the main subject of High Albania. It shows an old man of Shoshi, which is somewhere north of Albania's River Drin that flows towards its mouth near to Shkodra.

I hope that this small sample of illustrations drawn by the intrepid Edwardian traveller Mary Edith Durham serve to demonstrate her skills as an artist and illuminator.

IF YOU ARE INTERESTEDIN ANY OF THE FOLLOWING: ALBANIA, KOSOVO, the BALKANS,and TRAVEL,then you need to read "ALBANIA ON MY MIND" by Adam Yamey.This book is available on Amazon&by clicking HERE

Published on December 15, 2013 07:46

November 17, 2013

ALBANIA - a haven for the Jews

"Where religious prejudice and hatred did not exist"

Thus wrote Herman Bernstein about Albania in 1934, when he was the US ambassador to that country.

A house in Berat (Albania) where Jews were hidden in WW2 (Source: Click here)

Last year, I published a brief item on my blog (click HERE ) about the idea, which was briefly mooted in the 1930s, that Albania should be considered as a new 'homeland' for the Jews. So, it was with great interest that I began reading Harvey Sarner's book about the Jews in Albania.

It appears that Jews have lived in Albania since Roman times or maybe even before. During the 12th to 14th century, there were communities in what is now Albania and what is still considered to be 'Greater Albania', notably in the now Greek city of Janina. The expulsion of the Jews from Spain in the 15th century further increased the numbers of Jews in Albania. Until the 19th century, this small population of Jews lived peacefully with their Albanian neighbours. During the 19th century when nationalists, mainly Greeks, were trying to become independent of the Turks, there were several incidents during which Jews were massacred. These occurred mainly in Corfu and Janina, and have been largely forgotten.

During the first half of 20th century before WW2, Jews in Albania were tolerated by their gentile neighbours, both Moslem and Christian. The considered themselves, and were considered by others, as being primarily Albanian rather than Jewish, even though they did adhere to Jewish religious customs. They spoke Albanian rather than Yiddish, Hebrew or Ladino (as did Jews in Thessalonika). This may have been one of the reasons that protected them from the anti-Semitism, which was so rife elsewhere in Europe. Harvey Sarner proposes 2 other reasons for tolerance of Jews in Albania: they did not set themselves apart from other Albanians and they were not so numerous that their presence adversely concerned or made the rest of the population feel threatened (as in, for example, Thessaloniki or further away in Warsaw).

I could not help wondering whether the Albanians' tolerance for Jews would not have been stretched beyond its limit had the plan, mooted in the 1930s, to create a new home for the Jews in Albania been fulfilled. The small (a few hundred) population of Jews would have been greatly enlarged by the influx of large numbers of Jews who were not Albanian, and who had little or no interest in promoting Albania's interests ahead of their own. After all the Zionists did not choose to settle in what is now Israel primarily to promote the well-being of their gentile neighbours.

When anti-Semitism became the official order of the day in Europe after Hitler came to power and began invading Europe, Albania became one of the countries that accepted Jewish refugees. Some of these had been issued with visas, but many others had fled from neighbouring Yugoslavia and to a lesser extent from Greece. The Albanian people welcomed these unfortunate refugees, and protected them from being discovered by first the Italian and then the German invaders. When asked to prepare lists of Jews in Albania, the authorities refused to do so. This was in contrast with what happened in neighbouring Greece (and the Netherlands). In Thessalonika, I remember reading in another book, the Jews themselves prepared a list of the members of their community for the Germans, and another was prepared in Janina. Both of the these Jewish communities were murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators. In Athens, where such a list was not prepared, the Jews could not be rounded up until the Nazis resorted to a dirty trick, namely offering free supplies of Matzo flour during Passover. The Jews who collected this were rounded up, and massacred. In Albania, no lists were prepared, and the Albanians, who held the safety of guests as an ancient and sacred tradition, made sure that the survival rate of Jews in their country was almost, if not, 100%.

Sarner describes some of the individuals who protected the Jews and a few of the stories of Jews who were saved by them. It would have been nice to have heard more of these, but for those who are interested, let me recommend Escape through the Balkans: The Autobiography of Irene Grunbaum written by one who experienced life as a Jewish refugee in Albania, Irene Grunbaum. Sarner, in a later chapter of his book, describes his successful efforts to have some of the Albanian rescuers recognised as Righteous Gentiles in Israel's Yad Vashem memorial.

After WW2, Albania began to be ruled by the regime headed by the most faithful disciple of Joseph Stalin, Enver Hoxha. According to Sarner, there was no anti-Semitism under Albania's Communist regime - unlike many other countries that had entered the Soviet 'bloc'. Although Hoxha's government were never pro-Israel, they were not anti-Semitic. The country isolated itself from the rest of the world. Neither Jews nor anyone else were able to leave it. In 1967, Hoxha decreed that Albania was an atheist state. Mosques and churches were destroyed or closed; there was no synagogue to be closed. Religious practices were banned, and Albanians had to choose names for their children that did not give away their original religions.

6 years after Enver Hoxha died (in 1985), the Communist regime collapsed in Albania. It was at this point that many Albanians fled from their impoverished country, many of them to Italy where they were not welcomed with open arms! In contrast, Israel welcomed those of Albania's Jews who wished to live there, and with a few exceptions most of Albania's Jews, none of whom knew any Hebrew, took up the opportunity.

Sarner's book is crammed full of interesting information, but is, sadly, poorly edited. There are many errors and inconsistencies of spelling . At first, this put me off the book, but I am glad that I persisted, and read all of this fascinating but brief volume. I would have liked to have given this book 4 out of 5 stars for its interest value, but stylistically it only deserves 3.

READ MORE ABOUT ALBANIA

IN

ALBANIA ON MY MIND

BY ADAM YAMEY

Available as a paperback or Kindle on Amazon

Published on November 17, 2013 04:47