Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 236

December 15, 2013

An artist in Albania

I have just finished reading Edith and I , a book written by Elizabeth Gowing. I have reviewed it on https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/733589531 . It is about the life of Miss Mary Edith Durham (1863-1944), and concentrates on her visits to the area of the Balkans that is now the Republic of Kosovo. Miss Durham is known affectionately by modern Albanians, whose cause she championed before and after the First World War, as Mbretëresha e Malësoreve (the 'Queen of the Mountains').

Until I read Gowing's book, and then looked up Durham on Wikipedia, I had not realised that Miss Durham had been trained as an artist and illustrator long before she embarked on her travels to the southern Balkans. Long ago, I acquired an early edition of Durham's book entitled High Albania. It is a brilliantly written account of her travels in the rugged mountains of northern Albania and neighbouring Kosovo and of the people whom she met there.

I took a fresh look at my copy of High Albania, and realised that its author was indeed a fine illustrator. The rest of this article is dedicated to presenting a few examples of Durham's hand-drawn illustrations in her book. Her attention to detail was marvellous, as was her ability to capture the 'atmosphere' of a place. Despite the presence of her own photographs in her book, it is the drawings that help to make it really special.

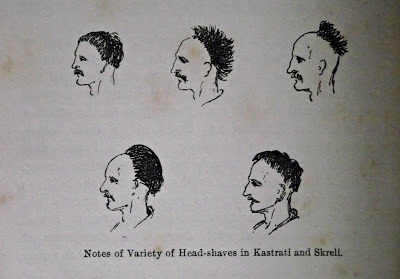

Of this picture, Miss Durham wrote, "To study head tufts one must go to church festivals. Only then are a number seen uncovered."

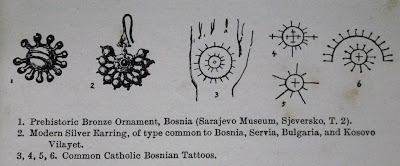

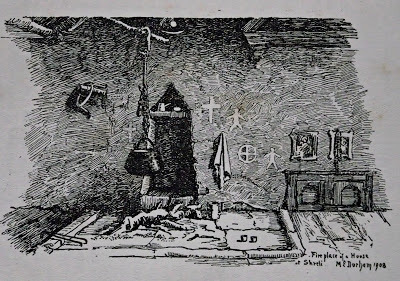

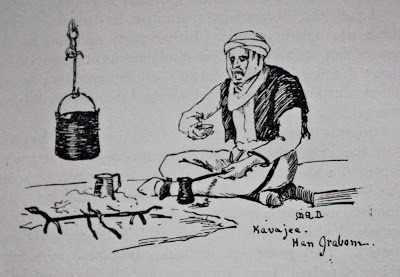

The two pictures shown above are of anthropological and/or ethnographic interest. It is not surprising to learn that Miss Durham's inherent ability to observe the characteristics of people and to report on them scientifically was recognised by the Royal Anthropological Institute (of Great Britain & Ireland) who appointed her a Fellow of it. The next 2 pictures illustrate Durham's skills in capturing both great detail and also the genreal 'atmosphere' of places that she visited.

The first of these two shows the interior of a house in Skreli, in the northern highlands of Albania. The crosses drawn on the wall next to the hearth indicate that the house was home to some of the many Albanian Roman Catholics who lived in the area. The second of these, the kavajee or coffee-maker, shows him holding the jezva, in which Turkish-style coffee is brewed, in one hand and the cup into which it will be served in the other. The next picture shows Durham's skill in depicting architecture.

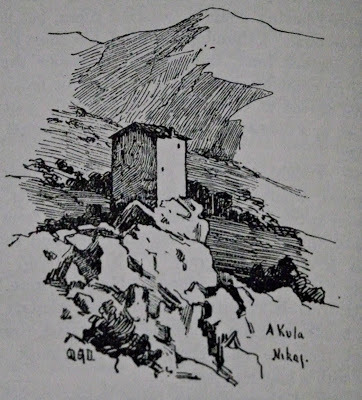

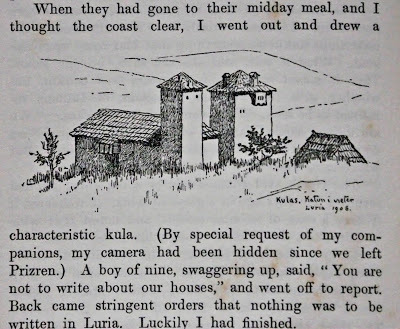

The drawing above, although very competent must have been drawn at speed, as the accompanying text, which I have copied, suggests. It shows a couple of kulle or fortified tower residences that are not only typical of the lands inhabited by Albanians but can also be found in the Mani Peninsular that projects from the southern Peloponnese (see my picture below).

As Gowing's book relates much about Durham' s visits to Kosovo, I have decided to include some of the pictures from High Albania that were drawn whilst Edith was there. Here is one showing a Serbian woman from Ipek carrying a cradle on her back:

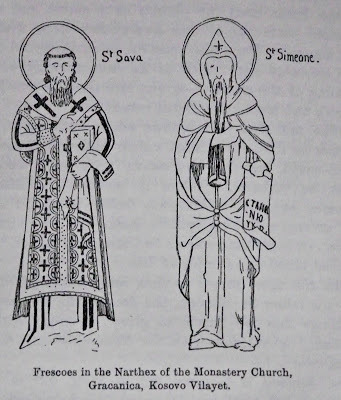

And, here is another one showing two of the fine frescoes inside the Serbian monastery at Gračanica ( Graçanicë), not far from the Kosovan capital as well as the site of the Battle of Kosovo Polje where the Serbs were narrowly defeated by the Ottoman army on the 15th June 1389.

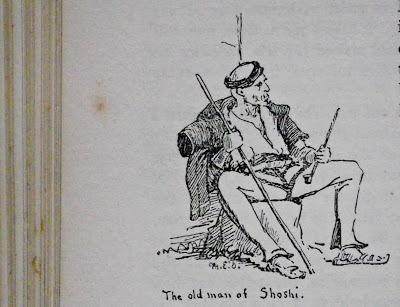

Today, visiting the monastery is not as simple as it was when I visited in 1990 (see my recently published book about Yugoslavia Scrabble with Slivovitz - click here ). When Elizabeth Gowing visited it, the Serbian monasteries in Kosovo had become like tiny rocks in a vast sea of Albanians. Surrounded by razor wire fences and guarded by heavily armed militia to protect these islets of Serbian culture from the Albanians, who rightly or wrongly lose little love for the Serbs, entry to them is subject to intensive identity checking and might be denied. The last of my examples of Durham's drawings brings us back to northern Albania, which is the main subject of High Albania. It shows an old man of Shoshi, which is somewhere north of Albania's River Drin that flows towards its mouth near to Shkodra.

I hope that this small sample of illustrations drawn by the intrepid Edwardian traveller Mary Edith Durham serve to demonstrate her skills as an artist and illuminator.

IF YOU ARE INTERESTEDIN ANY OF THE FOLLOWING: ALBANIA, KOSOVO, the BALKANS,and TRAVEL,then you need to read "ALBANIA ON MY MIND" by Adam Yamey.This book is available on Amazon&by clicking HERE

Published on December 15, 2013 07:46

November 17, 2013

ALBANIA - a haven for the Jews

"Where religious prejudice and hatred did not exist"

Thus wrote Herman Bernstein about Albania in 1934, when he was the US ambassador to that country.

A house in Berat (Albania) where Jews were hidden in WW2 (Source: Click here)

Last year, I published a brief item on my blog (click HERE ) about the idea, which was briefly mooted in the 1930s, that Albania should be considered as a new 'homeland' for the Jews. So, it was with great interest that I began reading Harvey Sarner's book about the Jews in Albania.

It appears that Jews have lived in Albania since Roman times or maybe even before. During the 12th to 14th century, there were communities in what is now Albania and what is still considered to be 'Greater Albania', notably in the now Greek city of Janina. The expulsion of the Jews from Spain in the 15th century further increased the numbers of Jews in Albania. Until the 19th century, this small population of Jews lived peacefully with their Albanian neighbours. During the 19th century when nationalists, mainly Greeks, were trying to become independent of the Turks, there were several incidents during which Jews were massacred. These occurred mainly in Corfu and Janina, and have been largely forgotten.

During the first half of 20th century before WW2, Jews in Albania were tolerated by their gentile neighbours, both Moslem and Christian. The considered themselves, and were considered by others, as being primarily Albanian rather than Jewish, even though they did adhere to Jewish religious customs. They spoke Albanian rather than Yiddish, Hebrew or Ladino (as did Jews in Thessalonika). This may have been one of the reasons that protected them from the anti-Semitism, which was so rife elsewhere in Europe. Harvey Sarner proposes 2 other reasons for tolerance of Jews in Albania: they did not set themselves apart from other Albanians and they were not so numerous that their presence adversely concerned or made the rest of the population feel threatened (as in, for example, Thessaloniki or further away in Warsaw).

I could not help wondering whether the Albanians' tolerance for Jews would not have been stretched beyond its limit had the plan, mooted in the 1930s, to create a new home for the Jews in Albania been fulfilled. The small (a few hundred) population of Jews would have been greatly enlarged by the influx of large numbers of Jews who were not Albanian, and who had little or no interest in promoting Albania's interests ahead of their own. After all the Zionists did not choose to settle in what is now Israel primarily to promote the well-being of their gentile neighbours.

When anti-Semitism became the official order of the day in Europe after Hitler came to power and began invading Europe, Albania became one of the countries that accepted Jewish refugees. Some of these had been issued with visas, but many others had fled from neighbouring Yugoslavia and to a lesser extent from Greece. The Albanian people welcomed these unfortunate refugees, and protected them from being discovered by first the Italian and then the German invaders. When asked to prepare lists of Jews in Albania, the authorities refused to do so. This was in contrast with what happened in neighbouring Greece (and the Netherlands). In Thessalonika, I remember reading in another book, the Jews themselves prepared a list of the members of their community for the Germans, and another was prepared in Janina. Both of the these Jewish communities were murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators. In Athens, where such a list was not prepared, the Jews could not be rounded up until the Nazis resorted to a dirty trick, namely offering free supplies of Matzo flour during Passover. The Jews who collected this were rounded up, and massacred. In Albania, no lists were prepared, and the Albanians, who held the safety of guests as an ancient and sacred tradition, made sure that the survival rate of Jews in their country was almost, if not, 100%.

Sarner describes some of the individuals who protected the Jews and a few of the stories of Jews who were saved by them. It would have been nice to have heard more of these, but for those who are interested, let me recommend Escape through the Balkans: The Autobiography of Irene Grunbaum written by one who experienced life as a Jewish refugee in Albania, Irene Grunbaum. Sarner, in a later chapter of his book, describes his successful efforts to have some of the Albanian rescuers recognised as Righteous Gentiles in Israel's Yad Vashem memorial.

After WW2, Albania began to be ruled by the regime headed by the most faithful disciple of Joseph Stalin, Enver Hoxha. According to Sarner, there was no anti-Semitism under Albania's Communist regime - unlike many other countries that had entered the Soviet 'bloc'. Although Hoxha's government were never pro-Israel, they were not anti-Semitic. The country isolated itself from the rest of the world. Neither Jews nor anyone else were able to leave it. In 1967, Hoxha decreed that Albania was an atheist state. Mosques and churches were destroyed or closed; there was no synagogue to be closed. Religious practices were banned, and Albanians had to choose names for their children that did not give away their original religions.

6 years after Enver Hoxha died (in 1985), the Communist regime collapsed in Albania. It was at this point that many Albanians fled from their impoverished country, many of them to Italy where they were not welcomed with open arms! In contrast, Israel welcomed those of Albania's Jews who wished to live there, and with a few exceptions most of Albania's Jews, none of whom knew any Hebrew, took up the opportunity.

Sarner's book is crammed full of interesting information, but is, sadly, poorly edited. There are many errors and inconsistencies of spelling . At first, this put me off the book, but I am glad that I persisted, and read all of this fascinating but brief volume. I would have liked to have given this book 4 out of 5 stars for its interest value, but stylistically it only deserves 3.

READ MORE ABOUT ALBANIA

IN

ALBANIA ON MY MIND

BY ADAM YAMEY

Available as a paperback or Kindle on Amazon

Published on November 17, 2013 04:47

November 10, 2013

PARIS WITHOUT EIFFEL

Four days in Paris during the autumn of 2013

TUESDAY 29 OCT 2013

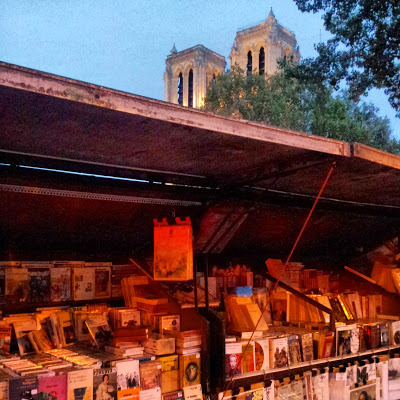

To celebrate our 20th wedding anniversary, we decided to visit Paris. Before setting off on the Eurostar train at London's St Pancras Station, I had some misgivings about revisiting a city which I had visited many times before. As soon as I stepped out of the metro train that took us from Gare du Nord to Place St Michel, these misgivings evaporated. Far from making me feel blasé, the sights of the city uplifted my soul. I felt as if I was seeing the city anew. I was filled with wonder. After taking possession of our room at the Hotel Esmeralda on the Rue St Julien le Pauvre - its window provided an excellent view of the north side of Notre Dame - we took the metro to the station named 'Stalingrad'.

We were hungry. Someone in a bar close to the station directed us to a nearby restaurant called Canal Huit. This moderately priced, unpretentious local eatery served food prepared to perfection. In addition to the marquise de jambon/chevre, which consisted of chunks of smoked ham stuffed with goats cheese, I also enjoyed beef sautéed with carrots in a richly flavoured reddish sauce - perfection. My wife ate a perfectly prepared entrecote. Satisfyingly replete, we strolled over to the nearby Bassin de la Villette, which used to serve as a port for boats using the canal system that served Paris before the advent of railways.

After looking at the Bassin, we began walking alongside the Canal St Martin that connects north-east Paris with the Seine, which it enters near to the Arsénale. At first the canal was lined by 'edgy' looking establishments, but nearer the centre of the city the canal becomes increasingly chic.

We watched a tour boat passing through one of the series of double-locks that allow ships to descend gradually to the level of the Seine.

And then we continued our pleasant stroll along the canal. Every now and then we encountered small parks along the water's edge. Often these were alongside the double-locks. Near the Place de la République, the canal disappears into a tunnel. We took a bus from the Place to Place St Michel. From there we walked to the famous bookshop called 'Shakespeare & Co.' (see: HERE for more detail), which was just around the corner from our hotel.

We waited there for the arrival of my cousin J-B, who has attended workshops at this famous establishment. Eventually, he appeared, and we accompanied him to the nearby Café Panis, which is an example of the nicest kind of traditional Parisian café. We chatted and enjoyed a supper together. After eating, we accompanied J-B to his RER station, and then took a walk around the lively part of the Quartier Latin near to our hotel.

St Severin

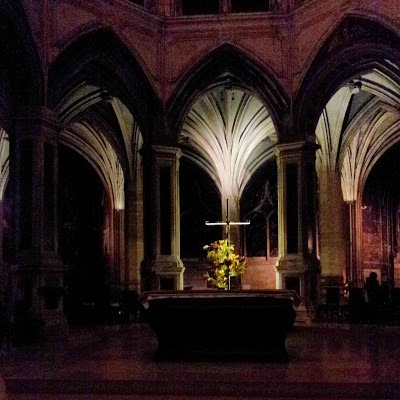

Before entering our hotel, we took a peek inside the nearby church of St Julien le Pauvre. We were able to enter it despite it being after 10 pm because a concert that had been held inside it had just ended. The church is now used by a Melkite Greek Catholic congregation. See below:

WED 30 OCT 2013

We awoke early in order to beat the queues that form soon after Notre Dame opens its doors at 8 am. I am glad that we did not have to queue as the interior of Notre Dame proved to be disappointing. Unlike many other Gothic cathedrals and churches that I have visited, the interior of N-D is sombre. It lacks the lightness and uplifting nature of other churches built at the same time as N-D. In contrast, its exterior is magnificent.

We looked at various places for breakfast. Most of the cafés in the vicinity of N-D and near to Place St Michel offer a pathetic 'breakfast menu' for at least € 7.50, that is more than £7. For this, all you are offered is a croissant, a hot drink, and a glass of orange juice. We left the banks of the Seine and walked into the Quartier Latin, where we found a neighbourhood bar. Here, we enjoyed 2 hot drinks and an excellent fresh croissant for under €5 for the two of us. We were served by a witty barman and his assistant. They made jokes as funny as any that you would associate with New York City banter. After this truly small petit déjeuner, we walked along the Boulevard St Germain and then the Rue Bonaparte, passing the house where the painter Edouard Manet was born.

St Germain des Prés

We arrived at the Musée d'Orsay just before 10 am, hoping to avoid having to join a queue, but found that a long one had already formed. The museum is housed in the shell of what used to be a railway station.

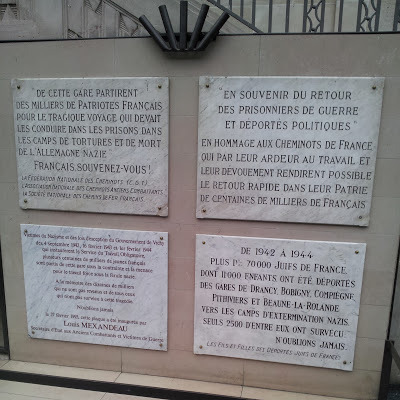

Just before joining the queue, we spotted a plaque on the exterior wall of the former station. It commemorated the deportation from this station of many innocent victims of the Nazis. While we were waiting in the line for the ticket hall of the museum in which we were hoping to enjoy seeing great works of art, I could not help thinking of those unfortunates who must have had to wait near or in this station in the early 1940s before facing a far worse fate. After 20 minutes, we entered the museum.

The best thing we saw in the museum was a well-displayed temporary exhibition called Allegro Barbaro. This is the name of a piece of music written in 1911 by the Hungarian composer Bela Bartok. The exhibition displayed paintings executed by Hungarian artists during the first 20 years of the 20th century. All of the paintings on show were of the highest artistic quality. Many were painted by Robert Bereny (1887-1953) and Joszef Rippl-Ronai (1861-1927). I particularly liked the only painting on display by the short-lived Joszef Nemes-Lamperth (1891-1924) and a couple of pictures by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946). However, all of the pictures were worth seeing.

The top floor of the museum contains a vast number of paintings by French Impressionist artists. Many of them were very familiar to me, having seen them often in reproductions. Each painting displayed was magnificent, but there were too many of them on display to be able to focus properly on individual works. Likewise, there were far too many visitors trying to view them, many of them clutching miniature electronic devices that looked like mobile 'phones. These gadgets fitted with headphones contain recorded information about selected paintings. There were too Manet (excuse the pun!) pictures and art pilgrims for my liking. Great as the pictures are, I feel that better places to enjoy the works of the Impressionists include the National Gallery and the Courtauld Institute in London.

Several floors beneath the Impressionist gallery there was a gallery containing works executed by Vincent Van Gogh whilst he lived in France. These hung alongside a number of paintings made by Gauguin in the Far East. Sadly, the crowd in this particular gallery was far too dense to enjoy these superb canvases properly.

The main space of the former railway station has been over-restored and wrecked. What must have once been a wonderful open space where passengers and porters milled around has been spoilt by the construction of step-like concrete partitions that break up the space unharmoniously. This poor treatment of space contrasts markedly with the successful handling of space in the cavernous former Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern in London. Both my wife and I left the Musée d'Orsay a little disappointed - not with the art, but with the building itself.

RER station beneath Musé d'Orsay

A long ride on a metroi train took us to the north of Paris, to the municipality of St Denis. We were hungry when we arrived, but could not face any of the 'fast-food' joints that we found near the town's main square. Eventually, we homed in on an isolated restaurant called 'Les Orangines'.

It was a time-warp. We felt as if we had stepped into a modest restaurant in provincial France in the 1960s or maybe before. It looked as if the place had not been decorated since then. When we entered, there was a bald-headed man sitting at a table directly beneath a large television screen, his eyes glued to the football match that was being broadcast with the volume turned off. Across the room next to the entrance to the kitchen there was another man with a bushy moustache. Both men were taking occasional swigs from their alcoholic drinks. Baldy was drinking Pastis; the moustachioed was drinking Scotch whiskey.

We ordered our meal from the friendly Algerian waiter, who, we discovered, was not Arab but Kabyle. While my wife awaited her cous-cous with merguez sausages and lamb kebab and I for my home-made meatballs, we asked the two other seated men whether they thought it would be safe for us to visit the Parisian district of Belleville. Baldy replied that he did not know because it was là bas in Paris rather than in his beloved St Denis. He added that it was full of les chinois unlike St Denis which was full of Pakistanis and other Moslems that he referred to as les barbus - the bearded ones. At this point the other man, the moustachioed, looked up from his drink and said that Baldy was racist. Baldy turned to him and said (in French, of course) "Yes, I am VERY racist ". The 2 men and the waiter all laughed. Shortly after this, Baldy described both Canada and India as being colonies of France.

The food arrived. It had been freshly prepared and was delicious. Usually, I do not enjoy cous-cous, but what was served was tastier than any that I had ever eaten previously.The meatballs were delicately flavoured. When I asked the waiter which meat had been used to prepare them, he replied beef. Baldy, who was nursing yet another glass of Pastis, hastened to add proudly that it was not just beef, but it was French beef. Every now and then, he made meaningless exclaimations whenever soething exciting happened on the screen above him. The mustachioed man stood up, went behind the bar, and helped himself to another large whiskey, and then, a few minutes later, a small pitcher of wine.

Baldy turned to us and asked if we had visited the Basilica at St Denis. When we told him that we were going to do that after eating, he began listing all of the attractions of his town of St Denis.He suggested that we should visit all of them after seeing the Basilica. He was very proud of St Denis, where he had lived for 62 years since leaving Spain, his native land.

Meals arrived for Baldy and the moustachioed fellow just after we had eaten ours. After serving the 2 other men, the waiter presented us with a large slice of sweet melon as a gift for our desert. After drinking coffee, we left Les Orangines, and headed for the Basilica of St Denis.

The interior of the gothic basilica is a complete contrast to that of Notre Dame. The nave was tall, light, airy, and uplifting. The apse, the north transept, and the crypt of the Basilica form the final resting places of many of France's royalty. At some point during the early 19th century (around about 1817), many royal tombs were relocated from places all over France and placed in the Basilica at St Denis. For an immoderate entry fee, we were allowed to look at this splendidly laid out collection of graves and funerary sculpture. A black marble slab in the crypt marks the resting place of Marie Antoinette, which lies next to that of her husband Louis XVI. A solitary fresh bouquet lay on her stone.

A long, slow bus ride brought us from the market place in the centre of St Denis to Porte de la Chappelle on the northern edge of Paris. On the way, we crossed the Canal St Denis, where I spotted a shanty town on one of its banks, which looked just a small version of one in Bombay, India. At Porte de la Chappelle, there were many gypsies waiting by the bus stop. Each of them was accompanied by a heavily laden shopping trolley.

We took a metro train to the Gare de l'Est. Above the entrance to the platforms there is a painting by Albert Hester, done in 1923, showing French soldiers setting off to war:

Elsewhere in the station there are monuments to those who were forced to travel against their will by the Nazis and their French collaborators in the 1940s.

We strolled along the Boulevard Strasbourg that connects the Gare de l'Est with the centre of Paris. Near the station many of the pedestrians were black Africans. There were many crowded, busy hair salons filled with Black women having their hair and nails done. After passing a couple of theatres, we turned off the boulevard and onto the Boulevard St Martin. A short way along it we came across the Porte St Martin:

We took a bus from there to Place St Denis, and ate at Café Panis, where we had eaten with J-B the day before:

For desert, I at a crèpe made at the Patisserie Sud Tunisien:

After that, we managed to enter the church of St Séverin, where we saw a religious painting with a Polish inscription beneath it.

THURS 31 OCT 2013

We are sitting in a café on the chic Ile St Louis. A little overpopulated with tourists, this small island in the Seine maintains the charm it had when I first visted Paris (with my parents) in about 1968. During that visit we stayed in the only hotel on the Ile. The hotel still exists, but is no longer the sole one and it is quite unaffordable. We have arrived on the island after a long trip form the the south to north-east of Paris.

This morning we began by travelling south towards the Place d'Italie. When our bus reached the Rue Monge, we disembarked to visit the Arenes de Lutèce. Surrounded by apartment blocks, this site contains the ruins of a Roman arena discovered in the 1870s.

After visiting this little-known archaeological site, which I first learned about from Ian Nairn' quirky guide book to Paris, Nairn's Paris (first publ. 1968), we headed for another of Nairn's recommendations, the much visited Rue Mouffetard.

After taking coffee in a small bar, where we were served by another witty barman, we entered the church of St Médard. The church is small and mostly gothic. The neo-classical pillars surrounding the high altar were built later than the rest of the church:

The Rue Mouffetard winds gently up a hillside. It is lined with foodshops displaying a wide range of mouthwatering foods - both ready-to-eat and also raw ingredients. Each display is a work of art:

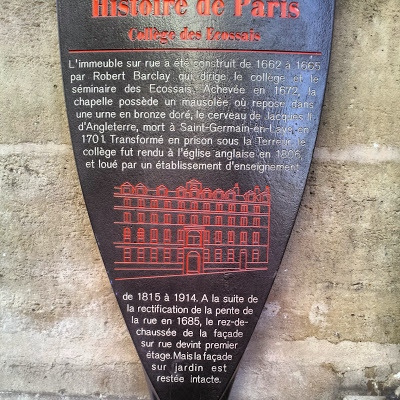

The road ends at a small attractive square at the summit of the slope. A road leads from there downhill towards the Seine, which can be seen in the distance. We passed the house where James Joyce wrote his Ulysses, and soon after that we reached the Collège des Ecossais.

A sign next to this old palace informs that the brain of King James II of England, who died in Paris in 1701, is stored in the chapel. He came to France when he refused to give up Roman Catholicism. We tried to enter the building, but were told that tourists need to make a prior appointment to do so. In general, it used to be the tradition in France that the corpses of royalty were dismembered, and the various organs, such as the heart and brain, would be interred in different locations.

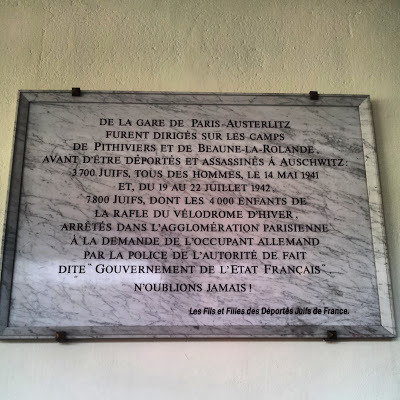

We took a bus to the Gare d'Austerlitz, where we made use of its elegant toilets. For a mere € 0.5 each we entered the suite of bathrooms and toilets, which looked more like a high class beauticians' salon than a railway station WC.

We caught a metro train from this railway terminal and headed for the north-eastern district of Belleville.

Metro station at Gare d'Austerlitz

Belleville is full of Chinese shops and restaurants. Amongst these we found and entered a modest-looking tiny Vietnamese eatery. We ordered three dishes that were prepared in the tiny kitchen in this establishment. We enjoye some of the best Vietnamese food that we have ever eaten.

The owner told us that he had come to France from Saigon 30years ago. When I asked to use the toilet, he told me that there was not one in his restaurant, but that he would take me to one nearby. I followed him out of the shop and down the street to the door to an apartment building. He opened this and took me through a leafy courtyard to the WC.

View from the 'loo'.

We walked up the steep Rue de Belleville, occasionally passing through vegetable shops that extended across the pavement and onto the roadway.

Eventually, we reached the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, a place that I have long wanted to visit having first learnt about it in Nairn's Paris many years ago. The centre-piece of this 19th century park that spreads across the slope of a hill is a cliff-like rock on the top of which there is a temple-like structure.

Many of the paths in the park were closed for repair, but that did not prevent us from seeing some of its attractions such as a delightful late 19th century café:

After leaving the park, we passed in front of the elegant 19th century Mairie of the XIXth arrondisement, before entering the metro at Laumange station.

We disembarked at Quai des Rapées, a station next to the Bassin d'Arsenale, where the Canal St Martin enters the Seine. We walked from there along the right bank of the Seine before crossing the Pont Sully in order to reach the Ile St Louis, where I wrote this entry.

As we walked along this central street on the small island we passed the church of St Louis-en-Ile, which we entered briefly:

After a refreshing beer on the island we crossesd another bridge onto the Ile de la Cité.

Having had a well-deserved rest in our hotel, we returned to Place Stalingrad to eat at the Canal Huit restaurant, where we ate a couple of days earlier. After eating another excellent meal there, we returned to the Bassin de la Villette, which is quite lively at night.

At one end of the Bassin thare ia a round building, La Rotonde designed in about 1784 by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux (1736-1806). It that now contains a restaurant. In former days it had been a customs house where dues were levied on imported goods brought to the city by the canals.

We returned to Place St Michel, where I ate a crèpe before we returned to the hotel.

FRI 01 NOV 2013

It was All Saints Day, a public holiday in France. The rain began in the morning and fell all day, but that did not deter us. We took an RER train to the Musée d'Orsay, and before crossing over the Seine on a modern foot-bridge, the Passarelle Solférino, a scruffy fellow picked up a shiny gold coloured ring from the pavement just in front of us. He asked my wife if it was hers. When she said it was not, he said that she should keep it anyway. We stepped onto the passarelle, and noticed that we were being followed by the scruffy man. He came up to us and asked us for money, claiming that he was hungry. We said 'non', and then he demanded that we return the ring, which we did. Moments later, we saw that he was trying the same trick on someone else.

The railings of the foot-bridge are covered with padlocks, love tokens. Apparently, there are so many of these that thier combined weight might threaten the integrity of the bridge.

We walked through the rain sodden Tuileries gardens, which have been disfigured by mediochre outdoor sculptures, and past the Louvre to the Rue Rivoli, which we crossed before entering the deserted courtyards of the Palais Royale.

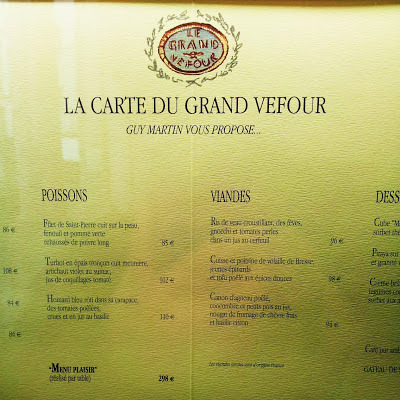

At the far end of the Palais, we passed the Le Grand Véfour, an elegant restaurant, with prices that are sky high - a set menu for €298, for example.

We continued walking through the rain towards Les Halles, stopping on the way at a beautifully designed café called Père et Fils for a coffee. We entered the magnificent gothic church of St Eustache in time to catch the tail-end of a service. As Ian Nairn once wrote, the organ's music seems to scrape away at the beautifully vaulted high ceiling of this building.

We ate la well-prepared lunch in a bistrot on Boulevard Sébastopol. After an aperitif of Pastis, I enjoyed Soupe à l'oignon followed by steak tartare. My wife enjoyed her serving of paté de foie gras de canard.

We continued to walk after we had eaten, and soon arrived at the Centre Pompidou. This building seems to have survived the passage of time well. An adventurous building, I did not think that it is as elegant as the Nat West Tower in London, which like the Pompidou Centre, also exposes its innards to the outside world.

St Merri seen from Place Stravinsky

After viewing the sculptures by Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint-Phalle that stand in the pool in the Place Stravinsky, we entered the nearby church of St Merri. Its spelling seems to be uncertain. Even within it we saw the saint's name spelled as both 'Merri' and 'Merry'.

The Rue des Rosiers, a Jewish district, not far from St Merri, was teeming with crowds of tourists. Many of them were queing outside counters selling beigels and falafels. A number of Lubavitch men dressed in black with tzitzes dangling from their belts were dancing in the streets and asking men, including me, whether they were Jewish.

A little further aloing the street, we passed a building (Hamam St Paul) that had once been the Jewish public baths. Next to it, there was a boys' school, which bore a plaque commemorating the deportaition of Jewish schoolboys to Auschwitz in 1943-44.

The 17th century Place des Vosges is truly magnificent. I had been looking forward to seeing it, but was a little disappointed. The square is surrounded by arcades in which there are now many art galleries selling unexciting works of contemporary art. Once, these vaulted arcades contained shops for the French aristocracy.

We took a bus from near the Place to Place St Michel. The route taken by the bus was fascinating as it involved driving through a narrow arch that entered the Louvre, passing the new glass pyramid before crossing the Seine near the Musée d'Orsay.

Sévres-Babylone

Cluny

We ended the day by eating dinner with another of my cousins at his home in the 7th Arrondisement. Next day, we set off for Strasbourg from the Gare de l'Est.

After returning to London, someone asked me whether we had seen the Eiffel Tower. I thought for a moment, and then realised that we had not caught even a distant glimpse of it during our few days in Paris

Metro Monge

NOW, READ ABOUT

ADAM YAMEY's

PUBLISHED BOOKS

ON:

http://www.adamyamey.com

Published on November 10, 2013 05:03

October 11, 2013

PUNK ROCK, FRIENDSHIP, AND SARAJEVO

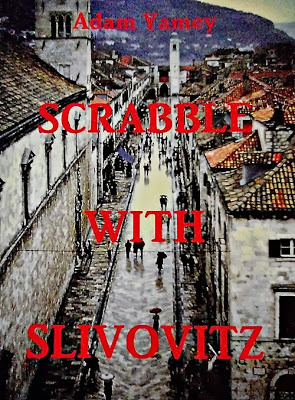

Between the years of 1967 and 1991, Adam Yamey visited Yugoslavia frequently, making many friends and enjoying a variety of interesting experiences. Recently, he wrote a book called SCRABBLE WITH SLIVOVITZ in which he relives and shares a diverse selection of his adventures.

In the first excerpt, he relates an episode that demonstrates the warmth and friendship of the peoples of a country that has sadly been torn apart by a tragic series of civil wars.

In the second excerpt, he describes how he attended one of the first ever punk rock concerts in the Yugoslav capital, Belgrade.

Get your paperback copy by clicking HEREGet your Kindle copy by clicking HERE

"Dubrovnik was the point of departure for my first visit to Sarajevo. I bought a ticket at the bus station just outside the walls of the old city, entered the bus, and headed for the seat, whose number was printed on my ticket. In those days, and maybe this is still the case today, passengers were assigned specific numbered seats on long-distance buses. Whenever I knew that I would be travelling a day or two ahead, I used to buy my ticket in advance in order to get one of the seats numbered 1 or 2, which were at the front of the bus, and therefore with the best view, and, incidentally, also with the highest risk of injury in a head-on collision.

On this particular occasion in the bus station at Dubrovnik, I found a young French tourist was sitting next to his girlfriend in my seat. I started explaining, in my poor French, that he was occupying my reserved seat. As I was doing so, a middle-aged woman, sitting near the rear of the bus, explained the situation in fluent French. The French couple vacated the incorrect seats and settled into their assigned places. These happened to be close to the woman and her friend. I could hear them conversing in French as we wound our way up along the valley of the Neretva Riverand away from the Adriatic coast. I felt a little miffed that they had found someone to converse with, but I had not.

After a few hours we stopped in a village perched high on a hillside. The young French couple said goodbye to their new friends, and left the coach. Our bus, which should have arrived in Sarajevowell before nightfall, remained parked on a steep slope in the small mountain village for hours. The few passengers who were continuing on to Sarajevo sat on a bench under a tree in the sultry afternoon sun. Eventually, I asked the lady, who could speak French, what was happening. She explained that one of the tires of our bus had been punctured, and that it was taking a long while to repair it. She revealed that she was an inhabitant of Sarajevo and that her travelling companion, an old friend of hers, was a school teacher from France. Finally, our bus was ready to depart. As it was now almost empty, I sat near to the two women and chatted to them. The sun was setting, and we were still only half way to our destination.

Soon after we began moving, the heavens opened. The mountainous region through which we were slowly making our way was filled with crashes of thunder and flashes of lightning. Torrents of rain made driving slow and difficult. I began despairing of ever reaching the city where the Hapsburg Archduke was shot in 1914. And, I was becoming concerned. I was heading for a city, which I did not know and where I had no accommodation arranged, and it was beginning to look as if would be almost midnight by the time we reached it. I asked Marija, the French-speaking lady from Sarajevo, whether she could recommend a hotel for me. She shrugged her shoulders and said that as she lived there, she did not know about hotels. At this point, her companion said to her in French,“Whenever I meet foreign students in my home town in France, I invite them to stay in my home.”Marija said nothing. It was my impression that she had not needed to hear this particular bit of information.

It was late at night when we eventually arrived in Sarajevo’s bus station. It was located far from the town centre on the main road that led to the spa at Ilidža. Miodrag was waiting for Marija, his mother-in-law, and her French friend. I was told to get into his car with them, and we drove along ill-lit rain soaked streets through the darkness of the night until we reached the end of a short, steeply inclined cul-de-sac in central Sarajevo. We entered Marija’s second floor flat, and Liljana, Marija’s daughter, served us a huge, tasty supper. At the end of the meal, I still had no idea where I would be spending the night. Before I could ask where I would be staying, Liljana showed me her mother’s spare bedroom, and told me (in good English) that I should sleep there.

After breakfast the next morning, I set off to find a hotel in which I could stay for the rest of my visit. It did not take long to find one and to reserve a room. Next, I bought a bunch of flowers - they were stems of gladioli - for my kind hostess, and returned to her flat. I entered, gave my bouquet to Marija, thanked her for looking after me, and told her that I had found accommodation. She told me not to be ridiculous; I was to cancel the hotel and to stay with her and her family."

"Every summer, there was a folk-music festival in Dubrovnik. We attended a few concerts, but these were never free of hassle. Most of my Yugoslav friends seemed to believe that it was beneath their dignity to buy tickets. Somehow, we used to smuggle ourselves into the concert without tickets, and then occupied seats which had a good view of the stage. Without exception, we managed to sit in seats that had been reserved by paid-up ticket holders. An argument would begin. There would be much swearing and even threats of violence. Eventually, a compromise was reached and everyone enjoyed the concert.

Whilst on the subject of concerts, let me whisk you away from the coast for a few moments in order to describe the occasion in Belgrade when Dijana invited me to join her and some of her friends to attend the first punk-rock concert ever to be held in the city. It was to be performed in the Students’ Cultural Centre (‘CKC’), an elegant late nineteenth century building in the heart of the town, which had once housed the Officers’ Club of Belgrade. We did not approach the main entrance, where a group of oddly dressed young people were queuing, but instead we went to a point on the pavement next to an open window. To reach the window it was necessary to cross a high cast iron fence topped with spikes. Dijana’s girlfriends scaled this easily, but I was unable to follow them; they had to return to carry me over it. We entered the building by climbing through the window, and stepped into the darkened concert hall, which was almost full.

The young audience, dressed in outlandish punk clothing, sat as quietly as if they had been awaiting a classical chamber concert at a place as sedate as London’s Wigmore Hall. The band appeared on stage and began strumming their electric guitars enthusiastically. Within seconds of their beginning, after fewer than two or three strums, the electrical supply fused, and we were plunged into an eerily dark silence. Soon, the lights returned, and we were all told to leave. The concert was, like the one which I had attended some years before in Zagreb, terminated prematurely. It was not the only concert that I attended in Belgrade, which I had to leave precipitately. Once, I was invited to attend a rock concert in a huge stadium in the city. It was a pro-Sandinista event. We left in a hurry to avoid becoming involved with the riot control police, who arrived on the scene soon after the performance began."

Published on October 11, 2013 08:13

September 22, 2013

AM I A CAMERA?

I knew that I had them. I knew where these foolscap (not even A4) pages were stored, stuffed into the pages of an old road atlas of Yugoslavia. But, I believed that they contained little more information than the list of places that I had visited with a friend when we drove around Serbia in 1990, the last time that I visited Yugoslavia. I was under the impression that the notes contained only the itinerary that we had followed when we visited lesser-known places in the heart of Yugoslavia, a country that was soon to be torn apart by uncivil civil wars.

However, when I did eventually take a look at these papers more than 20 years after having written them, I realised that I was wrong. These pages contained much more than a simple listing of where we had been and on which day; they contained extremely detailed notes about what we did at each of these places. At the insistence of the Yugoslav friend with whom I had made this trip in May 1990 I had kept a detailed contemporaneous record of our Serbian 'odyssey'.

I re-read these notes whilst I was working on the finishing touches to my book about Albania, "Albania on my mind", and it occurred to me that it would be interesting to write something about the numerous trips that I made to Yugoslavia between about 1967 and 1990. Thus, the idea of writing "Scrabble with Slivovitz - Once upon a time in Yugoslavia" (which I shall now abbreviate to 'SWS') was born. At first, I thought of writing up my 1990 notes into a short book, but soon after this I decided that I would trawl through my memories and try to write about the decades of experiences that I gleaned from visiting Yugoslavia.

I knew that I had taken many photographs during my numerous visits to ths country and its neighbours, but I had not seen them for over 20 years. They were all colour transparencies taken on 35 mm film. When I moved house in about 1993, all of these pictures were placed, along with many other surplus goods, into a lock-up in a warehouse a long way from where I moved in with my wife. I had no idea what condition they were in and what was depicted on them. Consequently, most of the text of SWS was based on what memories that remained stored in my aging brain. The only part of the book that was based on more than pure memory was my description of the last trip that I made to Yugoslavia (that was in May 1990).

Just when the manuscript of SWS was nearly ready for publication, the company which managed the long-term storage of our goods contacted us urgently. The section of the warehouse in which our storage locker was located was due to be remodelled shortly. The company needed us to move our goods to a new locker, and felt that it would be best if we were present to supervise the moving. We agreed, and whilst the moving was in progress I decided to take a look at some of the numerous boxes of colour transparencies that I had not seen for over 20 years.In each box that I examined, the colour slides were in pristine condition. We returned home, and I ordered a slide scanner from Amazon.

When the scanner arrived, I returned to our locker, and selected several boxes of slides including most of those that I had taken during my trips to Yugoslavia and its neighbours (SWS also describes excursions that I made from Yugoslavia to Bulgaria and Hungary). I scanned furiously for about 3 weeks until the scanner failed to function any more. I hasten to add that this was not due to over-use but to faulty electronics, which the supplier was gracious enough to acknowledge by making me a refund. Since returning the scanner, I have devised my own slide scanning apparatus, which, incidentally, produces far better results than the one that I bought. I may describe its construction in a future blog.

I had originally decided to illustrate SWS with pictures 'borrowed' from the Internet, from old books and old tourist brochures in my possession, but the rediscovery of my slides made me change my mind. I illustrated the book with my own photographs. And this is where the process of writing SWS became interesting. As I scanned the slides and turned them into digital images (.jpeg files), I realised that many of the things that I had written about, and which were based on what I could remember, were things that I had also photographed. It was if the act of taking the photograph not only made changes on the emulsion of the 35 mm camera film but also on my grey matter, or wherever it is that memories are stored in my head. Christopher Isherwood once wrote, "I am a camera...". Well, it appears that so am I!

The object of this little essay was to illustrate something of how my memory works, and I hope that I have succeeded in doing that. However, many of you may be wondering why Scrabble? Slivovitz or Slivovica almost everyone associates with the Balkans, and especially the lands which were once known as 'Yugoslavia', but few would have reason to associate Scrabble, a word game developed in the USA in 1938, with travels in the Balkans. Well, if you want to know why I played Scrabble in Belgrade (sometimes after eating Chinese noodles in Novi Sad) as well as Sijarinska Banja and Studenica, you will have to read my book!

"SCRABBLE WITH SLIVOVITZ - Once upon a time in Yugoslavia"

by Adam Yamey

is available by clicking HERE

OR via Amazon's online stores, where it is also available as a Kindle version.

Published on September 22, 2013 04:14

September 1, 2013

COAKER KODAI

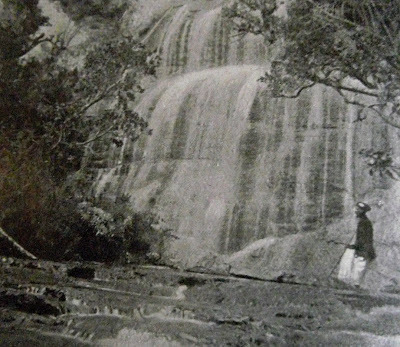

In July 2013, we visited Kodaikanal's Fairy Falls, illustrated above in a 1909 photograph, but we saw a very different sight:

The Fairy Falls were devoid of water. Despite the luxuriance of the vegetation in Kodaikanal, it is currently suffering from a lack of rainfall . The Bear Shola Falls, which we reached by a short footpath that was hemmed in by overgrown plants - many with beautiful flowers, was almost dry, but not quite:

The same was the case for Silver Cascades (illustrated in my earlier blog: CLICK HERE ). However from a distance, the artificial lake for which Kodaikanal is famous looks the same today:

as it did in 1909:

The 8 Km convoluted edge lake is bounded by a roadway.. This pleasant scenic pathway around the lake is lined with villas from different eras; stalls selling a variety of goods to visitors; and boat-houses. One group of stalls sells Tibetan goods:

There are numerous tea-stalls:

The biggest boat-house rents out anything from pedalos :

To fancy looking shikaras:

We hired a boat with an oarsman and spent about 45 minutes being rowed around a part of the lake:

There was a café in what looked like a very old Victorian dwelling:

This was closed as was the ferry station when we passed it:

We strolled around the lake on foot, but many rode on horses accompanied by grooms on bicycles:

There is a variety of trees around the water's edge, all labelled with interesting information :

At one point along the lake there was a park dedicated to the memory of an Indian patriot:

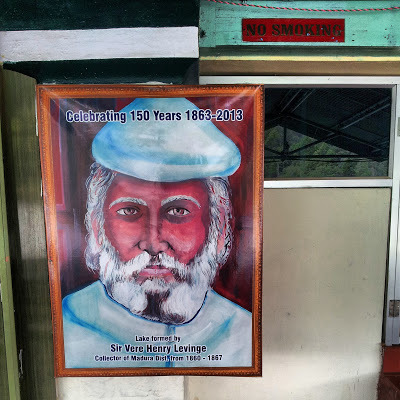

Maharaja Ripudaman Singh (4 March 1883 – 12 December 1942) was maharajah of Nabha, a Princely State in the Punjab , until 1923, when the British suspected him of nefarious deeds, and exiled him to Kodaikanal. Further around the lake, there is a monument to Sir Vere Henry Levinge(1819-1885), who created it:

Its celtic motifs make reference to his Irish origins. His portrait adorns a wall of one of the boathouses:

Within a few feet of this mnument to a British colonialist there stands a statue of Mahatma Gandhi. The lake is undoubtedly one of Kodaikanal's greatest features. Another one of these is only a few minute's walk awasy from the lake. It is Coaker's Walk, one of whose entrances lies close to the Van Allen Hospital , which was founded by Dr Van Allen in 1915. Coaker's Walk is named after Lieutenant Colonel Coaker who was on duty in Kodaikanal in 1872 when the path that runs around Mount Nebo was constructed in 1872. The views from Coaker's Walk are spectacular:

All along the path, there were stalls to amuse or distract those who hadd had enough of the panoramic splendour:

The other end of Coaker's walk is near the Doordarshan Television Tower, which may be reached after a steep climb up a forested slope. Here it is, partially enveloped by a passing cloud:

So much for outdoor attractions. Just outside the town in Shembaganur, there is a natural history museum that is in itself a museum piece:

It was founded in the 1920s by the Jesuit Philosophical Seminary of Sacred Heart, which is adjacent to it. The exhibits that have been collected by the students and professors of this institution include some curiosities including coins from the 'Saarland':

The obligatory animal skulls:

And a python spinal cord:

Even if you are not a nature lover, this antiquated museum is worth a visit. Now, you must be exhausted after all of this sight-seeing. I will reveal more about the attractions of Kodaikanal in another article

FOR SOMETHING COMPLETELY DIFFERENTREADADAM YAMEY's LATEST BOOK:

"SCRABBLE WITH SLIVOVITZ"

CLICK H E R E

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Published on September 01, 2013 09:39

August 25, 2013

A MISSIONARY POSITION

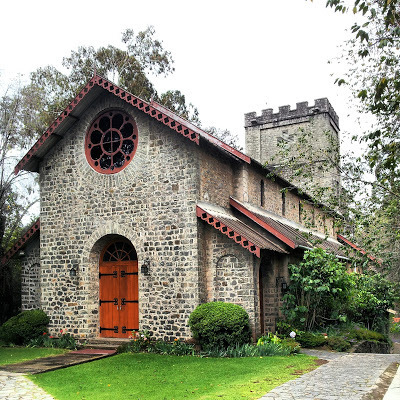

Even during the coolest time of the year, the temperature in the plains in the south of India can exceed 30 degrees Celsius. In summer, the sky's the limit! As the summer temperature soared in the plains during the 19th century, Europeans sought refuge from the heat in so-called 'hill-stations'. These included members of the American Madura Mission, who decided to set up their own hill-station in Kodaikanal. The Americans built their first church (illustrated above: picture from a 1909 guidebook) there in 1857. It was used for services until 1896 when a new church was built . By 1908, the original church had been demolished. Today, all that remains of this is an obelisk in the midst of the overgrown American Cemetery:

The cemetery is close to one of the earliest dwellings - if not the earliest - to have been built by the American Missionaries:

This building is still privately owned by some Americans and is, like the other remaining original building, built without foundations. The successor to the original church is the Union Church, which is near one of the entrances to Coaker's Walk:

We noticed a wall-mounted clock inside the church. It looked quite old, and had been supplied by a company in Madras, but had been made in the USA:

The Americans were not the only non-British 'Europeans' to settle in Kodaikanal. They were joined by Swedes and Germans. Scarcely anything remains of the Swedish settlement apart from an indication of its location on a map issued by Tamil Nadu Tourism at the rather basic tourist office on PT Road, which is almost opposite a small, super short-order restaurant called Pot Luck. The German Missionary Church stlll stands alongside its separate wooden bell-tower and is in good condition:

Two stone crosses surrounded by a circle of thorns stand near to the bell-tower. They are without inscriptions. Maybe, they mark graves. It is difficult to say whether this is the case.

A commemorative stone in the church's south wall reads as follows:

I

ISadly, I cannot find any information about this pastor G Lohmann on the Internet. This old church, which we were unable to enter, is not the only Lutheran church in Kodaikanal. There is another one opposite the main buildings of Koadikanal International School:

Within the grounds of Kodaikanal International School ('KIS'), which were priviliged to be shown around, we saw another of the town's churches. The construction of the school's chapel began in the 1930s. It is named in honour of the school's first Principal Margaret Eddy (1848-1935)

The school was founded at the beginning of the 20th century by members of several missions. Roughly 50% of its about 600 students come from outside India.

The KIS is close to a complex of restaurants that includes a pizza outlet. There is nothing surprising about this in a town with so many students, but the pious exhortations on the signboard outside it are unusual:

Maybe, we should not be so surprised as a missionary atmosphere does seem to pervade the town. We visited two other churches in the town. One of them overlooks the road that leads from Kodaikanal down the ghats to the plain far below.

This church, the Sacred Heart Church, is a Roman Catholic parish church built in 1910 to accommodate the growing Catholic congregation in Kodaikanal (For more information, click HERE ) . Here are some views inside:

The Sacred Heart was not the first Catholic church in the town. That honour goes to the Church of Our Lady of La Salette, which was built in 1866. This fine edifice stands high above the town close to the Doordarshan television tower and Hindustan Unilever's mercury thermometer factory, and also a compound whose rusting gates proclaim that they give access to the 'Oceanic Shrimping Company'.

Here is a picture of the steps leading up to the venerable church:

And here is a view of its interior:

We noticed something hanging in the church's porch. It looked rather like an embroidered Holy Icon:

We saw another of these at the Sacred Heart Church (mentioned above):

A statue of Our Lady of La Salette stands close to the La Salette Church and above its circular souvenir shop:

I have described the churches that we managed to visit in Kodaikanal. We would have liked to have investigated St Peter's Church, but it was closed each time we passed it.

Although churches predominate the landscape of Kodaikanal, there are also mosques and temples. This mosque is in the heart of the bazaar area:

And this temple, the Kurinji Andavar Temple is on the edge of town close to Chettiyar Park:

Given that Kodaikanal was built in a position chosen by Christian missionaries, I will not dwell further on these non-Christian places of worship.

READ ABOUT ADAM YAMEY'SPUBLISHED WRITINGBY CLICKING: HERE

Published on August 25, 2013 00:00

August 17, 2013

ICEBERG

The former headquarters of the White Star Line in Liverpool

A Chinaman and a Jew are sitting together in a railway compartment.After a while, the Jew gets up and hits the Chinaman.“Why did you hit me?” asks the victim.“For Pearl Harbour,” the Jew replies.“But I’m Chinese”“Chinese, Japanese it’s all the same to me.”

The train continues on its way.Some hours later, the Chinaman gets up, and hits the Jew.“Why did you do that, already?”“For the Titanic”“But I’m Jewish.”“Iceberg, Greenberg, it’s all the same to me.”

This afternoon (17 Aug 2013), we attended a performance of Titanic at the Southwark Playhouse. It is a musical drama written in 1997. It is based on a book by Peter Stone. Its lyrics and music were composed by Maury Yeston (born 1945).

This music drama rivals any that the Brecht/Weill team wrote. It is dramatic, powerful, incisive, interesting, informative, and brilliant musically. Titanic addresses the important social problems of the class system such that existed just before the First World War (‘WW1’), and still linger on today. The cast directed by Danielle Tarento sing and act beautifully. They mesmerised the audience with their energy, acting skills, and, not least, their beautiful singing. This performance of a drama with great political significance is all of the following: humorous, tear-jerking, exciting, moving, thoughtful, and realistic. As the drama unfolded, it was difficult to believe that we were not aboard that ill-fated liner.

The sinking of the Titanic in April 1912 serves as an unintentionally true-life allegory of much of the 20th century. The liner, built by Harland and Wolff in Liverpoolfor The White Star Line, was described as being unsinkable. As an Unknown Titanic crew member is supposed to have said to an embarking passenger, Mrs Sylvia Caldwell, “God himself could not sink this ship!” (see note below)While we all live our daily lives distracted by trivial, yet important enough, problems and pleasures, we, like the passengers on the Titanic, remain largely unaware that our world might be sailing towards yet another iceberg.

Note: click here

Click HERE to read Adam Yamey's new bookaboutY U G O S L A V I A

Published on August 17, 2013 14:20

August 12, 2013

GETTING UP THE GHATS

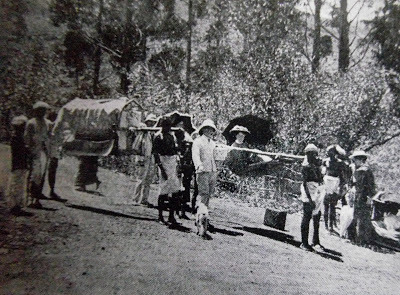

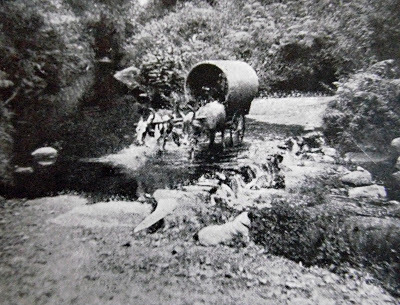

This is the first of a series of articles that I intend to write about Kodaikanal. If you should be fortunate enough to visit this southern Indian hill-station in Tamil Nadu, make sure that you buy a copy of Zai Whitaker's excellent guidebook Kodai Cocktail ( publ. by Ecumenical Book Services, Chennai, India: 2012). In it she refers to a guidebook published in 1909 by 'E.M.M.I.' and Lillingstone of Kodaikanal. I found a copy of this detailed book on the Internet, and bought it. The black and white illustrations in this article and others that I hope to write came from this venerable book.

This article deals with our journey from Bangalore to Kodaikanal by road in July 2013. We did not travel in a chair carried by local Indians as is illustrated in the picture above, nor did we travel in the superior successor to this mode of transport illustrated below.

These pictures were taken before a 'decent' road , the Law's Road was opened in 1916. We travelled in a brand new Suzuki Dezire from Bangalore. After leaving our daughter at Bangalore's international airport at 4.30 am, our driver Hanumaya drove us southwards right across Bangalore toward the Karnataka/Tamil Nadu border, which we reached soon after sunrise. We stopped at the RTO 'check-post' at Zuzuwadi, which is on the outskirts of Hosur, and after a long delay our driver paid the 100 Rupee tax that allowed us to drive in Tamil Nadu.

Hanumaya proved to be a bold driver. Between Bangalore and Dindigul, we travelled along a modern highway. Our speed never left the range 120-140 km per hour except at the numerous toll-booths that we had to pass. Although it was not particularly congested with traffic, there was some. Hanumaya was determined that none of this would slow us down. We overtook and undertook. If two trucks were overtaking, Hanumaya would shoot through the steadily closing gap between them. If two vehicles were moving towards each other, he would squeeze between them, narrowly missing contacting either of them. His driving was truly a ride of the 'white knuckle' variety.

Soon after we had left Hosur, I noticed that Hanumaya was getting sleepy. The car was drifting - at high speed - from one side of the carriage way to the other. Hanumaya, who had picked us up at 3.30 am, must have left his home an hour earlier. I suggested that we stop at a roadside café, which was part of an hotel, in order that he could take a nap. While he was fast asleep, we had coffee, but before that we needed the toilet. The proprietor of the café unlocked one of the rooms of the hotel (see below), and told us to use its en-suite bathroom.

We continued our journey after Hanumay had slept for 45 minutes. Every now and then, he stopped for a cup of tea. Here is a shop at one of these stops. Notice that its owner has placed mask-like rakshasas to ward off the evil eye.

After several hair-raising hours of dare-devil driving, we reached Dindigul, where we left the motorway. Had Hanumaya been less tired, we would have entered this town. We decided to visit it on our return. We joined the road that led towards Kodaikanal. It was not a dual carrigeway, but this did not mean that our driver needed to reduce his speed; he did not. We drove on westwards until we reached the small town of Periyakulam in which there was a huge traffic jam because a festival was in progress:

We realised that we had missed the turning for the ghat road leading up to Kodaikanal, and made a u-turn in the midst of all the festive chaos around us. After an anxious 20 minute drive retracing our steps we saw the sign to Kodaikanal and began ascending the winding road that was to take us up to 2500 metres above sea-level. At first, the road was quite good. Every now and then we encountered troupes of monkeys sitting by the roadside. They scattered away as we sped towards them.

Further on, the road deteriorated in patches, causing Hanumaya to consider slowing down a bit.

We had the feeling that Hanumaya was not familiar with mountain driving. He took curves at high speed, swinging the steering wheel around violently using only one hand. I cannot recall how many near misses we had as we met vehicles speeding down the road in the opposite direction.

We climbed upwards for the best part of an hour and a quarter until we reached a toll-booth where we had to pay a small fee for entering the district of Kodaikanal. Soon after this, a few hair-pin bends later, we arrived at a wonderful waterfall called Silver Cascades.

The falls, were were informed, were less spectacular than usual on account of poor rainfall. Near to the falls, I saw something that looked like a parody of an artwork by Damien Hirst:

It was in fact a collection of balloons that formed a shooting range for visitors to test their skills as marksmen. There was a line of stalls near the falls. They offered a variety of things for visitors. We selected one of the many tea-stalls at random and bought cups of ginger tea. This is made with freshly crushed root ginger, milk, tea powder, sugar, and powdered dried ginger. After this lot has been boiled up, it is strained through a cloth filter, and poured into cups. Here is our tea being cooled:

The tea was so delicious that we made at least one special trip out of Kodaikanal to drink it at this particular stall. Its owner told us proudly that his son was a university student studying engineering. After refreshing ourselves with his tea, we continued driving upwards until we entered the town of Kodaikanal. The temperature was about 11 degrees Celsius It had been well over 32 down in Dindigul.

We booked in at the Kodaikanal Club, an ex-colonial institution dating back to 1887. We were given a spacious room in the new block. It was nearer the dining room and other club facilities than the rather more picturesque original Victorian rooms:

Before retiring for the evening, we took a stroll around Kodaikanal's bustling bazaar area.

On our way to this we passed a few fancy shops selling spices, dried fruits, and locally made chocolate, something that I would not advise anyone to even consider tasting even the smallest of pieces!

THIS SERIES OF BLOGS ABOUT KODAIKANAL TO BE CONTINUED

Find out more about Adam Yamey's writingby clicking H E R E

Published on August 12, 2013 01:47

July 11, 2013

RUSSIAN IN BANGALORE

Luminous streaks of clouds traverse the eerily lit, crisp outlines of the Himalayan Mountains. I have never seen these lofty peaks at the roof of the world in real life. So, these images that I have are only second-hand. They derive from seeing the magnificent series of paintings by the Russian-born artist Nicholas Roerich (1874-1947). These hang in the art gallery of the Karnataka Chitrakala Parisath ('CP'), a prestigious art college in Bangalore.

The CP is located near the end of Kumara Krupa Road furthest away from the Windsor Manor Hotel. It is set amongst extensive grounds. A large vestibule, open to the elements, gives access to a number of rooms on the ground floor. These include a ticket office, which doubles up as a bookshop, and some larger rooms that are used to house occasional exhibitions of hanficrafts. When I visited recently, one room contained a display of flower arrangements and another a sale of handicrafts made in Rajasthan.

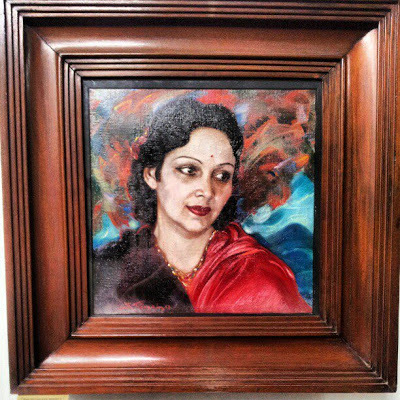

The permanent exhibition of artworks is housed in rooms on the labyrinthine first floor. The first of these rooms that one reaches after ascending the staircase contains the series of pictures of the Himalayas to which I have already referred. Nicholas Roerich, who was already an accomplished painter in Russia, his native land, had already left Russia when he began traveling in Asia in the mid 1920s. By 1928, he and his family had settled in India where he lived out the rest of his life. His son Svetoslav (1904-1993) was also a prolfic painter. A couple of galleries in the CP are dedicated to displaying his highly colourful works, which in my opinion are not as fine as his father's but good nevertheless. He married the Indian film star Devika Rani, and painted her portrait frequently. He died in Bangalore.

Although I consider the collection of Himalayan pictures painted by Nicholas Roerich to be the highlight of the CP, there are many other delights to be discovered in its ill-lit, dingy rooms. One of these contains paintings mainly by Bengali artists. The earliest of these is a collection of paintings by artists of the Kalighat school who worked in 19th century Calcutta. Paintings by members of the Tagore family including Rabindranath and Abinandranath can be seen in this room as well as some political cartoons by another relative Gaganendranath. These reminded me of the somewhat grotesquely sinister works of the German artist Georg Grosz. The works of other artists hanging in this room show the influence of European artists who were breaking the mould in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s.

Moving on, we reached some rooms containing a wide selection of paintings and sculptures from artists who were/are working in more recent times. Although many of these works were created during the last 20 years or so, they are so badly conserved that they seem as if they were made many years earlier. The lighting in these galleries was poor even after it had been switched on. This is a great shame as many of the works on display are of the highest quality.

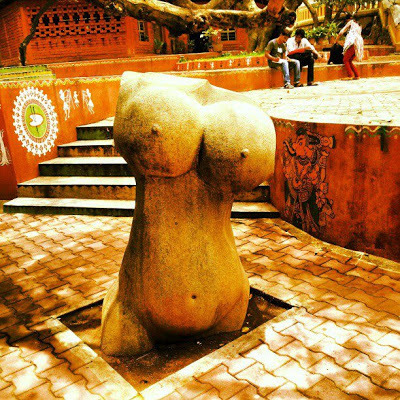

As one moves deeper into the building, one enters rooms containing everything from the sublime to the ridiculous. I will not dwell on the latter too long, but it includes sculptures that are, in my humble opinion, unworthy of public display. Two of the many rooms are worthy of a visit. Although difficult to find, the search is worth the effort.

One room contains a collection of beautiful Karnatakan leather puppets. They resemble other oriental marionettes such as those used in the Javanese shadow plays. However, they look fragile and are badly displayed, often being attached to their backing displays by ageing pieces of adhesive tape.

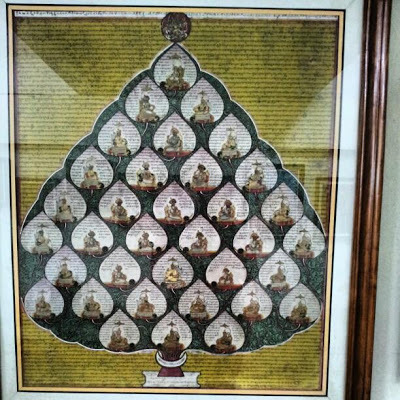

Another room, deep inside the gallery contains a collection of Mysore paintings that date back to the 14th century. Many of the paintings on display at the CP were painted far more recently than this. One of them, which particularly intrigued me, was a genealogy of the Mysore Royal family (see above). Another picture in the collection showed the influence of the Company Style of painting, popular with British patrons stationed in India during the 18th and 19th centuries (see below).

The grounds of the CP contain a newly opened café, a branch of the Kamat chain; the college's library and sculpture studios; various other out-houses; a Hindu shrine; and a multi-leveled garden studded with sculptures. Occasionally, these grounds host 'Dastakar', a fair filled with stalls selling folkloric crafts from all over India.

Until a few years ago, the CP became the nucleus of one of the most wonderful art events in Bangalore, Chitra Santhe. This event used to be held on the last Sunday of each year. The whole of Kumara Krupa Road was closed off to vehicular traffic. Artists lined the road with stalls from which they sold their works of art. Some were professional, many were students. We bought many beautifully painted watercolours from them over the years. Sadly, this event is no longer held. I do hope that it will be re-instated as soon as possible! The picture below was taken at one of these events.

The collection of art exhibited at the CP is of a far greater quality than that at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Bangalore ('NGMA'), which I wrote about earlier (see: http://yameyamey.blogspot.co.uk/2013/07/best-in-bangalore.html ). However, the care given to displaying the works at CP is far inferior to that at the NGMA. Also, the latter is very fortunate in that it is housed in a heritage building of great beauty. This said, any art lover visiting Bangalore would be well-advised not to miss devoting some time to exploring the superb collection housed in the CP.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT

ADAM YAMEY's WRITING

PLEASE VISIT:

http://www.adamyamey.com

AND

http://www.yugobook.com

Published on July 11, 2013 06:19