Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 228

December 6, 2017

IN THE GODS' OWN COUNTRY - ISLAM & CHRISTIANITY IN KERALA

Until recently, I had blithely assumed that Islam entered the Indian subcontinent from its northwest fringes – from Afghanistan and elsewhere. In November 2017, I made a trip to Kochi (Cochin) in Kerala during which we were taken to see a mosque, the first to be built on the Indian subcontinent. Built long before the Mughal invasion, it is in the Kodungallur district on the estuary of the River Periyar, about thirty kilometres north of Ernakulam. I learned that this small area of southwestern India is of historical significance for at least three religions.

Kodungallur, watered by the River Periyar and backwaters, was a globally-important historical economic area, variously known as: ‘Muziris’, ‘Cranganore’, and ‘Shingly’. Until it silted up (many centuries ago), it was one of the ports where much trade (export of: spices, textiles, pearls, gems, and other exotic valuables) occurred between foreigners from the west and the local inhabitants. The silting resulted from the opening-up of a passageway for the River Periyar from the lagoon to the Arabian Sea at Cochin (now ‘Kochi’). This reduced the flow of the river through the backwaters between Cochin and its original mouth near Kodungallur, and caused its consequent clogging up.

Long before the invasion of the Portuguese in the 15th century (AD), these foreigners included the Greeks, the Romans (who were great consumers of pepper from Kerala), the Arabs, the Jews, the Chinese, and many others. The Romans spent so much on pepper that ancient authors recorded that it led to a great depletion in the empire’s coffers. Once, I visited a museum in Kozhikode (Calicut), which had many examples of foreign coins (Roman and otherwise) that had been found in the area. Extensive finds of ancient foreign coins have also been made in the Kodungallur area.

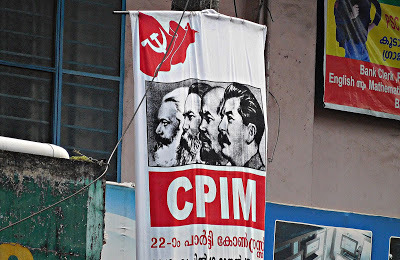

After crossing the water in a vehicle ferry from Fort Cochin, we drove along the long, slender Vypin Island through luxuriant, densely populated, countryside towards Kodungallur. The roads in this crowded tropical Garden of Eden were richly ‘decorated’ with flags and posters bearing the hammer and sickle of Communism, and placards showing portraits of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and, sometimes, Stalin and/or Che Guevara. The Communists have been an important and, most say, a constructive political influence in Kerala since the 1950s.

When we parked in Kodungallur, I spotted a banner with a fine portrait of Stalin opposite the Cheraman Jumma Masjid. This mosque was established during the life of, or very shortly after the death of, the Prophet Muhammad (c. 570-632 AD).

It is said that one night the Hindu ruler of Kodungallur Cheraman Perumal (a member of the Chera dynasty) had a dream in which the full moon was split in two. No one could explain the meaning of this until he met some traders, who had sailed across from Arabia. Their explanation led Cheraman to travel to Mecca, where he met the Prophet Muhammad, and became converted to Islam. He sent word back to Kerala that his people should embrace Islam and follow the teachings of Malik bin Deenar (died 748 AD), whom he dispatched to India. Cheraman, who remained for some years in Arabia, died on his way back to India.

When Malik arrived in Kodungallur, he was permitted to build what is now called the Cheraman Mosque. This was the first ever mosque to be constructed on the Indian subcontinent. Nothing remains of the original building. It was reconstructed in the 11th century, then again in the 14th. In 1504, the mosque was destroyed by the Portuguese when Lopo Soarez de Algabria (c. 1460-1520) attacked Kodungallur (see: “Muslim Architecture of South India”, by M Shokoohy, publ. 2003). Later, it was rebuilt, and in 1974 it was enlarged and surrounded by a modern structure. What the visitor sees from outside is largely unexceptional apart from the tiled roof of the oldest part of the mosque which can be seen above the modern extensions.

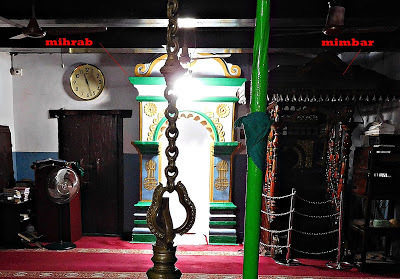

Male visitors may enter after washing their feet in a special area close to the mosque. I was shown the inner sanctuary, which is all that remains of the pre-1974 building. A remarkable feature is a large metal lampstand in which oil lamps (‘diyas’) may be held. This lampstand would not look out of place in a Hindu temple. The wooden ‘mimbar’ (pulpit) is elaborately constructed and delicately decorated. Next to it is the ‘mihrab’, a niche in the wall facing in the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca, with its semi-circular arch. This is a part of the mosque built in the 16th century. There are two graves draped with red and green silk cloths in a small room leading off from the inner sanctuary. These are the graves of Habib bin Malik and his wife Khumarriah. A door beyond the graves leads into a poky room from which women are allowed to view the graves. Although Malik bin Deenar was the first ‘Ghazi’ (leader) of the mosque, he handed it over to his relative Habib after a few years. Malik was buried elsewhere in Kerala (at Kasaragod).

The museum and gardens of the mosque are open to all. The garden has an attractive square tank (rather like a Hindu temple tank), where fishes swim. It is next to a cemetery. I noticed that several trees growing nearby were home to a colony of large bats, who hung from branches upside down and motionlessly.

The museum attached to the mosque contains a lovely model of what the mosque must have looked like before it was modernised. Like some historic mosques that I have seen in Kozhikode, the earlier Cheraman mosque, was similar architecturally to Hindu temples (and other buildings) in Kerala. Other exhibits included photographs and a wooden funeral bier. I was thrilled to stand where Islam made its first concrete foothold in India. This shrine is a site that is more evocative than visually interesting. I was told that the mosque has very few foreign visitors, who are neither Muslim nor Arab, and that I was one of its rare ‘white’ tourists.

From the Cheruman Mosque, it is a short drive to the Thiruvanchikulam Mahadeva Temple (‘Mahadeva’ for short). This Hindu temple, probably first built in the 8thcentury (AD), is dedicated to Shiva. The earliest recorded reference to it is in some Tamil hymns, which were first recorded in writing in about the 10thcentury. With its many steep, often gabled, tiled roofs, it is a typical example of Keralan temple architecture. Some buildings within the temple’s compound have several roofs, each one projecting from different levels of the building, producing a pagoda-like effect that is characteristic of many temples and other buildings in Kerala.

The white outer walls of the central building, the inner sanctum, are covered, from ground to roof-level, with dark timber planks arranged to form a huge lattice of rectangles, rather like a huge set of pigeon-holes. At the base of each rectangle, there is a small horizontal metal dish that can be used to hold oil and a taper. When lit, each of these little dishes become small diyas (lamps).

To the rear (east) of the central sanctuary, there is a shelter supported by eight thick circular columns with Doric capitals. Immediately east of this, but within the walls of the compound, there is a tall pagoda-like building whose stone walls are covered with elaborately carved pilasters. This building is above the compound’s eastern doorway.

Under the shelter, we saw a set of weighing scales. These are used to weigh offerings to the temple. For example, a donor would sit on one of the weighing pans, whilst his gift (be it rice or gold) is loaded on the other pan until it weighs the same as its donor. The scales were close to a tall metal lamp stand used for oil lamps. A simple wooden ladder rested against it. This is used to place, and light, diyas out of reach at the top of the tall stand. The base of the stand was sculpted in the form of a tortoise. Set into the floor surrounding the lampstand there were several prostrate women carved in stone, their clasped hands pointing towards the stand. Between them and the inner temple building, there was a ring of seated metal sculpted deities, each with four arms.

Many of the roof gables were decorated with painted sculptures of religious figures. Some of these supported the edge of the tiled roofs of the gables like caryatids. Apart from the buildings already described, the compound contained several smaller buildings housing shrines. Unfortunately, during our visit there was nobody about to unlock any of the buildings including the main temple.

Less than six kilometres southwest of the Temple lies the St Thomas Shrine (in the district of Azhikode) also known as the ‘Marthoma Church’. It stands close to the north bank of the River Periyar about two kilometres from its entry into the sea. It is at, or near, this spot where the apostle St Thomas is supposed to have landed in India in 52 AD, some five to six centuries before Islam reached the same district. I have injected an element of uncertainty because some authorities have proposed that Thomas first set foot in India in various places far away from Kerala. However, many agree that he landed first somewhere near to modern day Kodungallur, and this has been commemorated by the shrine, which was built in its present incarnation in the early 1950s. It replaces an earlier church in old Cranganore, which was destroyed during a battle between the (Roman Catholic!) Portuguese and the Muslims in 1536.

The shrine that faces the lovely tree-lined shores of the River Periyar is a flamboyant construction painted in white. The domed church, which lacks any architectural merit and contains a relic of St Thomas, lies between two sweeping curved colonnades topped with statues. The relic was brought to Kerala from Italy in 1953. The whole structure, church and colonnades, looks like an elaborate wedding cake or the set for a Bollywood dance routine.

Between the church and the water, there is a tall shiny metal column surmounted by a golden cross with two cross-bars. This high structure resembles those often found in or outside Hindu temples (used for holding diyas). We noticed that these columns, inspired by those associated with Hindu temples, are becoming quite common outside churches in Kerala. Both in mosques and churches that I have visited in India, features ‘borrowed’ from Hinduism can be found within them. Despite the introduction of ‘newer’ religions such as Christianity and Islam, it seems that Indian worshippers do not entirely abandon their ‘Hindu heritage’.

There is a colourful building, the Marthoma Smruthi Tharangam, which is next to the church and behind one of the colonnades. Its imaginative architectural style defies categorization. You might describe it as ‘A Keralan Disneyland meets the Vatican’. The building houses a theatre where ‘digital shows’ describing the life of St Thomas and the story of his relic may be watched.

St Thomas is believed to have been martyred in Chennai. There is a cave, which I have visited, at the top of St Thomas Mount in Chennai, where the saint was speared. It contains a slab of rock in which there are two hand-shaped impressions, which are believed to have been made Thomas’s hands. This cave, like the shrine at Kodungallur, attracts many pilgrims.

When St Thomas landed in Kerala, there were already Jews living there. Shortly after his arrival, following the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD, many more arrived as refugees. Jewish people have been associated with Kerala for a long time. For how long, the historians disagree. Most agree that Jews on King Solomon’s trading vessels visited the Keralan ports about 900 years before Christ’s birth. These Jewish mariners are believed to have brought exotic items such as peacocks, monkeys, and ivory from India to Solomon’s palace in the Holy Land. It is unlikely that any of Solomon’s people settled in Kerala.

From some centuries before and after the birth of Christ, Cranganore was ruled by the Chera dynasty. The Cheras permitted the settlement of Jewish people in Cranganore. Their descendants lived in India until after independence (in 1947) and the foundation of Israel, where many of India’s Jews migrated (for economic reasons).

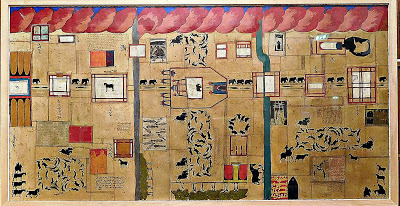

The Cheras allotted the Jews a small piece of land, named Anjuvannam, in the Cranganore district, which became a ‘Jewish kingdom’. Its inhabitants collaborated in many fruitful ways with their Chera, and then later, Chola hosts.

Various factors including the silting up of the Periyar as well as the decline of the Chera dynasty and their succession by the rival Cholas, caused many of the local Jewish people to move to Cochin. However, some Jews remained in what remained of Cranganore after it became less important than Cochin. The Jewish ‘kingdom’ of Anjuvannam continued after the fall of the Chera dynasty, which fell in the 12th century. By the time that the Portuguese began establishing themselves in Kerala, the Jewish community in Cochin was much more significant economically than that in Cranganore.

Today, several synagogues still stand in the Kodungallur, the old Cranganore, area. There was a total of twelve in Kerala during the heyday of Jewish presence in the state. We visited two synagogues near Kodungallur. Both have been looked after well, but are no longer used for worship. The two that we saw are far less-visited than the well-known and undoubtedly beautiful Pardesi Synagogue in bustling Mattancherry, in whose Jew Town the Jewish traders, of which only one remains, have been replaced by mainly Kashmiri Muslim traders, who are, incidentally, excellent salesmen.

The Paravur synagogue was first established in the 12th century AD, and then renovated by David Yakov Castlier in the late 16th, or early 17thcentury. Its architecture is typically Keralan. The first floor of the front entrance building has a deep veranda beneath a tiled roof supported by four pairs of columns. A covered passageway lined by stout columns leads from the entrance to the synagogue itself. The roof of the corridor is lined with wood.

The synagogue’s interior is simple. The original fittings have been moved to Israel, and have been replaced by replicas. If you were unaware of this, you would believe that you were seeing the originals. The carved wooden ark, or cupboard, in which the Torah scrolls were kept, has been reproduced, but is empty. The centrally located circular ‘bima’ or pulpit is wooden, constructed with turned wood balustrades. As with other synagogues in Kerala, there is an upper bima, which is formed by a semi-circular platform projecting from the first-floor gallery where women worshippers were required to be. The upper bima, a speciality of Keralan synagogues, was used only on special occasions, whereas the lower one was for routine use.

Women worshippers entered their first-floor gallery by way of the covered corridor running above that which connects the entry building to the ground floor of the synagogue. This upper corridor is lined with wooden slats which curve outwards from the floor towards the arched ceiling. In cross-section, this corridor resembles the hull of a boat. The slats sheltered women from the sun, and, also, made them difficult to see from outside.

Descriptive notices and photographs line the walls of the synagogue’s buildings. These provide information about Jewish life as it was in Kerala. From Paravur, it is a short drive (about two kilometres) to the smaller Chendamangalam Synagogue, which is close to the left bank of the Periyar. This synagogue was first built in 1420 AD, rebuilt after a fire in 1614, and renovated several times since. In the grounds in front of the main entrance, there is a small stone memorial to Sara, daughter of Israel, who died in 1269. This might have been brought by the Jews who migrated to Chendamangalam in the 13th century.

The entrance hall of the synagogue leads into the main prayer space through a door surrounded by colourful paintwork. Glass lamps of various designs hang from the colourful wooden ceiling decorated with carved, painted lotus flowers. The centrally located circular wooden bima is similar in design to that at Paravur. As in Paravur, there is an upper bima, which forms part of the gallery reserved for women. The female congregants stood or sat behind wooden lattice-work screen, the ‘meshisah’, hidden from the men during services. A staircase leads from the main entrance to the women’s area behind the screen. Another staircase with carved wooden banisters allowed the clerics to climb up from the main prayer area to the upper bima without having to see the women.

The ark, which was used to contain the Torah scrolls, is made of colourfully painted teak wood. There are three intricately carved pillars decorated with floral motifs on either side of the cupboard doors. The doors are also covered with painted plant motifs in bas-relief. The luxuriant decorative vegetation continues as decoration on the parts of the ark above the doors. Red, green, and gold are the colours which figure most on this almost baroque piece of furniture.

In the small grounds within the synagogue’s perimeter walls, there are a few gravestones with inscriptions in Hebrew.

I noticed a carved circular stone, whose perimeter was carved with a ring of leaf-shaped depressions. These were probably filled with oil and tapers, and then lit to be used as diyas. Thus, we find the diya holders characteristically used in Hindu temples not only in temples but also in mosques, churches, and synagogues. The reason for this is likely to have been because this was the normal form of lighting in India of old.

Most of Kerala’s Jewish folk have left for foreign parts. Neighbouring the synagogue in Chendamangalam, there is a newly built house bearing a Jewish name plate. The guardian of the synagogue told us that this was the home of a Keralan Jew who had left for Israel, but had returned to Kerala to live out his retirement.

We returned via the Vypin ferry station to Fort Cochin, where we were staying. On our way we drove along roads decked with Communist (and, also, BJP) banners. Our route took us past peaceful, rustic backwaters with occasional Chinese fishing nets. These backwaters are far more pleasant than those near to Alleppey, which are unpleasantly congested with boats and house-boats used by tourists.

Our brief visit to the Kodungallur district, a centre of global trade many centuries ago, was fascinating. It is an area, where four religions co-exist peacefully, and where two of them are supposed to have entered the Indian subcontinent. While reading about the history of this small corner of Kerala, one thing impressed me. That is, the almost complete lack of certainty about its early history. Like St Thomas, its story is full of doubts. To quote the small guidebook I bought at the Cheraman mosque:

“Total absence of reliable historical records make early history of Kerala a bundle of legends.”

PLEASE VISITADAM YAMEY'SWEBSITE:http://www.adamyamey.com

November 24, 2017

EXPLORING INDIA WITH A BABY

It was early in 1996. We never intended taking our nine-month old daughter to visit Hampi in the Indian state of Karnataka to see the ruins of the once great city Vijayanagara, which had in its heyday rivalled Rome in its splendour. We had hoped that her grandparents in Bangalore were going to baby-sit for us, but just before my wife and I were about to depart they felt unable to oblige. So, with little preparation, we boarded the sleeper from Bangalore to Hospet, the nearest town to Hampi. My wife clutched our little one on a narrow, hard, swaying railway bunk bed, desperately trying to prevent her from falling off.

At Hospet, our hosts, officials at a local mining company, greeted us with banners which they had made for us. They drove us to a comfortable hotel, whose rooms lacked air-conditioning and fridges. The ambient temperature never dropped below thirty Celsius, even at night. When our daughter needed a bottle of milk, we prepared it, and had to use, and then dispose, of it in less than 45 minutes because in that heat the artificial milk deteriorated rapidly.

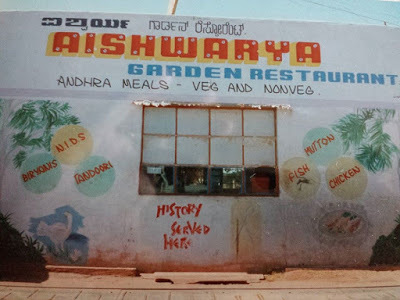

Hospet in 1996 was less sophisticated that it was, say, a decade later. We ate in simple restaurants, often outdoors under shades. Our daughter took a shine to the South Indian food that we were usually served. She took this from our plates and, also, to our horror, off the not too clean floor. Years later, I can report that unlike many of her school friends she has never suffered from allergies. I am sure that her foraging in Hospet is to some extent to be thanked for that.

Occasionally, I felt like eating North Indian food. We found places, which bore the notice “NIDS”, which meant ‘North Indian dishes served”. I should have known better than to order a ‘NID’ in a very provincial South Indian area, but I did, and was usually disappointed by the curious concoctions that appeared on my plate. On one occasion, I ordered a ‘Peshawari naan’, something that I love. What arrived was surreal. It looked like a circular pizza base that had been painted bright green, and it was covered by bits of dried fruit and fresh banana. It was almost, as they say in the USA: ‘close, but no cigar’.

Optimistically, we had taken a folding ‘buggy’ to Hospet. This never got used, as there was hardly a square metre of ground smooth enough to roll it. Luckily, our hosts drove us around the vast archaeological site in a large four-wheel drive. Our daughter, sat happily perched on or other of our laps as we bounced across the rough ground between the various attractions.

In 1996, the ruins at Hampi were in a far better condition than they are now. For example, the Vittala Temple with its musical pillars was in fine condition. Now, it is a sad shadow of what it was in 1996. It has been vandalised by evil-doers as well as by the authorities, who have tried to save it from collapsing by adding hideous concrete supports. Back in ’96, it was possible to wander from one attraction to another through a landscape romantically dotted with fragments of earlier civilisations, both Hindu and Islamic. In contrast, today the major attractions are walled off, and attract entry fees. Although I consider Hampi still to be a most exciting archaeological area, it has lost some of the charm that it had when we visited with our baby. She has not only visited Hampi thrice since and is planning another trip soon, but has also grown up to become a professional art-historian. I like to think that her early exposure to mediaeval Indian art has played a role in the evolution of her professional interests.

Our baby had no difficulty with the high temperatures and discomforts during our visit to Hampi and Hospet. She seemed to have enjoyed it immensely. Not only that, but so did the locals. Wherever we went, and this was true of most other places that we visited in India in 1996, she was adored by everyone including total strangers. We had thought that I, a ‘gora’ (a fair-skinned non-Indian), would have attracted attention during our trip from Bangalore, but this was not the case. I was ignored, but our little child was mobbed by well-meaning passers-by, especially little boys who patted her affectionately and told us how sweet she was.

Some short while after our trip to India, we visited Italy, a country famed for spoiling children with affection. At the end of our visit, we concluded that the Indians are far more ‘soppy’ about little children that even the Italians.

Enjoy books written by the author-dentist, ADAM YAMEY.Visit: http://www.adamyamey.com

October 21, 2017

A SURPRISING VILLAGE IN ESSEX

James Thorne wrote (in his “Handbook to the Environs of London”) in 1876: “East Tilbury is curiously out-of-the-way and old world like…”. It retains its feeling of being out-of-the-way, but no longer looks old world. Apart from the church, its rectory, and the fort, there are four cottages dated 1837. The rest of the buildings are much newer. The same goes for the village’s only pub, The Ship, which was rebuilt in 1957 when it looked the same as it does today. There has been an inn on its site since the 18th century, and maybe earlier. I had a mediocre lunch in the pub. I thought that was nowhere else to eat in the small village, but later discovered that the Fort (see below) has a café.

James Thorne wrote (in his “Handbook to the Environs of London”) in 1876: “East Tilbury is curiously out-of-the-way and old world like…”. It retains its feeling of being out-of-the-way, but no longer looks old world. Apart from the church, its rectory, and the fort, there are four cottages dated 1837. The rest of the buildings are much newer. The same goes for the village’s only pub, The Ship, which was rebuilt in 1957 when it looked the same as it does today. There has been an inn on its site since the 18th century, and maybe earlier. I had a mediocre lunch in the pub. I thought that was nowhere else to eat in the small village, but later discovered that the Fort (see below) has a café.

The flint and rubble gothic church of St Catherine contains much fabric dating back to mediaeval times, back to the 12th century. When viewed from the north or east, the church does not appear to have a tower. The reason is that the tower and part of the south aisle were destroyed by naval artillery in a battle between the British and the Dutch at Tilbury Hope in 1667. According to contemporaneous church records, by 1667 the tower was already in a poor state. Some say that it might have collapsed without the help of military intervention.

From the south side of the church, you can see an ugly square-based stone addition to the old church. This stump is all that was built of a replacement tower begun in the First World War by men of a garrison of the Coalhouse Fort (see below). It was to have commemorated those fallen in WW1. However, the authorities stopped the building works because the builders were not following correct procedures. Across the road from the church, stands the Rectory, an elegant brick building with large windows. It was built in the early 1830s to replace an earlier one which had been badly damaged in the battle mentioned above.

The village’s only thoroughfare continues downhill, almost to the north bank of the Thames. It ends at the car park for visitors to the Coalhouse Fort. During the early 15th century following an infiltration of the Thames by the French, King Henry IV allowed the inhabitants of East Tilbury, at that time classed as a ‘town’, to build defensive ramparts. In 1540, King Henry VIII ordered that a ‘blockhouse, be constructed at Coalhouse Point. This point on a curve in the Thames is so-named because by well before the 18thcentury coal was being unloaded from craft at this ferry point close to the village. The coal was transported westwards towards Grays and Chadwell along an ancient track known as the ‘Coal Road’.

In 1799, when it was feared that the French led by Napoleon Bonaparte would try to invade via the Thames, a new gun battery was built at East Tilbury. In the 1860s, when another French invasion was feared, a series of forts were built along the shores of the estuary of the Thames. One of these was the Coalhouse Fort at East Tilbury. Thus, the by then somewhat insignificant village became part of London’s defences.

The Fort was built between 1861 and ’74. Surrounded by a semi-circular moat and raised on a mound, the Fort is not particularly attractive. However, it is set in beautifully maintained parkland. From the slopes of the mound, there are great views of the Thames, which sweeps around the point, and its rural southern shore. The moat is separated into two sections by a short sharp-ridged stone wall, which was likely to have been built when the Fort began to be constructed. When I looked for the Fort on old detailed (25 inch to the mile) Ordnance Survey Maps (pre-1939), the moat is marked, but the Fort is not (probably, in theinterests of security). A ‘Coalhouse Battery’, which ran more-or-less parallel to the village’s only street was marked as “dismantled” on a 1938 map, but not the Coalhouse Fort.

The outer walls of the Fort have had all manner of later structures built on them: gun-emplacements, searchlight emplacements, and other shelters, whose functions were not obvious to me. There is a large concrete bunker outside the Fort, between it and the moat. Its shape might be described as three intersecting concrete blocks. This is marked on the tourist map as a ‘minefield control tower’. I believe that was it used to control electrically-fired mines in the estuary. Nearby and closer to the river, there is a smaller concrete bunker. The Fort’s interior was closed when I visited it, but I was able to get a peek through its main gates, which were open. Tramway tracks lead into the Fort. Old maps show that these led from the Fort to a small landing stage at Coalhouse Point, which is a short distance southwest of the Fort. The Fort ceased to be used after 1957.

Just over a mile north-west of the Fort, the road to East Tilbury Station passes through a most fascinating place. One of the first things you will see along the road from the Fort is a vast factory, which closed in 2005. Made of concrete and glass, but in a poor state of decoration, its flat roof carries a high water-tower labelled ‘Bata’. This was part of the factory complex that the Bata Company began building in 1932.

The Czech Thomas Bata (1876-1932) was born in the Moravian town of Zlin. He became the founder of Bata Shoes in 1894 in Zlin. He modernised shoe-making by moving it from a craftsman’s process to and mechanised, industrialised one. Bata’s company also revolutionised the way industrial enterprises were run, introducing a profit-sharing system that involved all of its workers, and provided a good reason for them to work enthusiastically. During the period between the two World Wars, the forward-thinking Bata opened factories and individual companies in countries including: Poland, Yugoslavia, India, France, Holland, Denmark, the United Kingdom and the USA. The company in India is still very active, almost every small town or village having at least one Bata retailing outlet. I have bought many pairs of comfortable Bata-manufactured shoes from Bata stores in India.

In anticipation of WW2, Bata’s son, the prudent Thomas J Bata (1914-1980), and one hundred other Czech families firm moved to Ontario (Canada) to form a Canadian Bata company. After WW2, the Communist regimes in Czechoslovakia and other ‘iron-curtain’ countries nationalised their local Bata firms. Meanwhile, Thomas J continued to develop the Bata firms in Canada and the UK, and opened up new Bata companies and factories in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America.Bata senior was keen on the ‘Garden City Movement’. He was concerned that his workers lived (close to his factories) and worked in a pleasant environment, and lacked for nothing. A pioneer of this in the UK was Titus Salt, who built his gigantic mill in the 1860s near Bradford in West Yorkshire. He created a new town, Saltaire, around his textile factory. This consisted of better than average homes for all of his workers (and their families) from the humblest to the most senior. In addition, he built schools, a hospital, open-spaces, recreation halls, a church, and other requisite of Victorian life. In Zlin, Bata created something similar, a fully-equipped town for his workers in park-like surroundings around his factory in the 1920s. The homes he built for the workers are still considered desirable today.

The factory at East Tilbury, was another example of a town built specially for its workers. One lady with whom I spoke there told me that she had worked for Bata’s for twenty-seven years. She told me that in its heyday the Bata ‘town’ was self-sufficient. It had workers’ homes, shopping facilities (including a supermarket and a Bata shoe store), a restaurant, a hotel, a cinema, a school, a library, farms, and playing fields.The factory buildings at the East Tilbury site, some of which have been adopted by other businesses, were built using a construction system devised (employing reinforced concrete frames that allowed for great flexibility of design) by the Czechs Frantisek Lydie Gahura (1891-1958), Jan Kotera(1871-1923), and Vladimir Karfic(1901-1996). The site bought by Bata in Essex in late 1931 was ideally placed in level open country near to both the railway and the river. His intention was to build a vast garden city around his factories, which was to produce boots and shoes in East Tilbury.Mr Bata senior was killed in an air-crash in 1932 near Zlin, and so never saw the completion of his creation in Essex, whose construction only began in early 1933. Construction of the factory buildings and the workers’ housing went on simultaneously. By 1934, twenty semi-detached houses of the same design as those in Zlin were built by local builders, and equipped with Czech fittings. The houses look just like many houses built in Central Europe. As Steve Rose wrote in The Guardian newspaper (19th June 2006):“East Tilbury doesn’t look like it belongs in Britain, let alone Essex, and in a sense it doesn’t. It’s a little slice of 1930s Czechoslovakia, and the most Modern town in Britain.” Later, more homes were built, but designed like many British suburban houses.

There is a huge building across the main road opposite the factory buildings. Part of its ground floor is now home to a Co-op supermarket. The whole building, which has now been converted to flats, was the ‘Bata Hotel’. Until recently, the Co-op was still named the Bata supermarket. One man, who has lived in the Bata Estate for many years, told me that he recalled seeing swarms of workmen in white protective clothing crossing the road from the factory and then entering the hotel during their lunch-break. He told me that the first floor of the hotel was a ‘restaurant’ for the factory workers.

I met this man in what is now called ‘East Tilbury Village Hall’. This was formerly the Bata cinema.Looking somewhat Central European in design, the former cinema was undergoing much-needed electrical re-fitting. In a way, I was lucky because the workers had left the door open to a building that is often locked closed these days. I entered the foyer, which was being used to store the stock of the local public library. An office to the left of the foyer used to serve as the cinema’s ticket office. A couple of old-fashioned film posters have been put on the foyer’s walls to recreate what it used to be like.

A man, who oversaw the hall’s maintenance, showed me the auditorium. It had a new wooden floor marked out for indoor sports. He explained that the floor had been ‘sprung’ when it was laid originally. This was so that it could be used as a dance-floor. The banked chairs for the audience were originally designed in an ingenious way, only lately beginning to be employed in other much newer buildings, so that they could be folded away when the hall was needed for, for example, a dance. There was a proper theatre stage at the far end of the hall. This still has the original stage lights that were fitted when the hall was built. The old-fashioned control panel for this lighting was still in place.

My guide then told me that beneath the stage, there was a reinforced bunker for use during air-raids. He took me through a door at the back of the stage, and then down some concrete steps. At the bottom, there was a heavy metal sliding-door painted grey. He slid this open to reveal the large reinforced concrete bunker beneath the stage. Its walls were thick. It is now used as a storage area.After seeing the old cinema, I entered the large grassy area to the south of it. In the centre of it, raised on a stepped plinth, there is a war memorial. The memorial bears the words: “… to the memory of those of the British Bata Shoe Company who gave their lives for freedom 1939-1945”. To the south of the memorial park, there is a large field, now used for agricultural purposes, that was once a Bata playing field.

Across the road from the war memorial in the grounds of the factory, there is a statue of Thomas Bata senior, who died in 1932. When I visited it many years ago (in the late 1980s), it stood in a small green area, a little park. During my recent visit (October 2017) it was surrounded by tall piles of sand being used by building contractors. Some of the Bata factory buildings have already been modernised and are being used for industrial or commercial operations. The main large derelict building, which is surmounted by a water tank, might be destined for conversion into ‘loft apartments’ for residential use. One building, a small tall construction near the main road, remains derelict at present. It might, one informant suggested, have been used for milling activities.During the early 1980s, British Bata began greatly reducing its production activity at East Tilbury. The Bata industrial estate finally closed in 2005. With the closing of the British Bata firm, Bata shoe-retailers, which were common in British high streets, have disappeared. The nearest Bata shoe store to the UK is now in Best (just north of Eindhoven) in the Netherlands.

From having been one of the bastions defending London from naval attack along the River Thames, East Tilbury became home for an exciting and successful industrial enterprise. Now, the extensive vestiges of this are being restored and re-used in an attempt, which looks like being successful, to keep the area alive and prosperous.

READ FASCINATING BOOKS BY ADAM YAMEY

DISCOVER MORE HERE:

http://www.adamyamey.com

October 15, 2017

DAVID HOCKNEY IN BRADFORD

The renowned contemporary artist David Hockney was born in Bradford (West Yorkshire) in 1937. In the suburbs of Bradford, there is an art gallery, Cartwright Hall, which Hockney used to visit in his youth. He said of this place: “I used to love going to Cartwright Hall as a kid, it was the only place in Bradford I could see real paintings.” He used to visit it as a schoolboy and young student during the 1940s and ‘50s. In July 2017, the establishment opened a new gallery dedicated to Hockney’s works. It was to see this that we set off by bus (a ten minute ride) from Bradford to Lister Park in which the Hall is located. What we found exceeded our expectations.

The building of Cartwright Hall (as a purpose-built art gallery) was financed by Samuel Cunliffe Lister (1815-1906), the son of a Bradford textile mill owner. Lister became wealthy through the development of new and improved textile mill technology. The house was named after Edmund Cartwright (1743-1823), an inventor of various textile processing machines including one for wool combing, which contributed greatly to Lister’s financial success. Modestly, Lister named the Hall after the inventor rather than himself.

Lister Park is extensive. It includes a fantastic feature, The Mughal Garden. If it had not been for the miserable grey sky and the absence of the Taj Mahal, with a little bit of imagination one might mistakenly believe that this garden was a replica of the water features that the Mughals delighted in creating in what became (in 1947) India and Pakistan. Opened in 2001, this garden, designed in conformity with Mughal gardening convention, reflects the cultural affinities of Bradford’s large South Asian community. This exotic-looking place, set within a conventional British municipal park, is in harmony with the multicultural range of exhibits within the Gallery.

The neo-classical Cartwright Hall was designed by the architects JW Simpson and EJ Milner Allen, both from London. Its interior is spacious, not in the least bit stuffy or airless (as for example is the National Gallery in Edinburgh).

Stained-glass by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

We began by looking at some of the works that Hockney might have examined during his youthful visits. These include paintings by well-known artists such as: Romney, Gainsborough, Reynolds, Vasari, Reni, and many of the Pre-Raphaelites. Mingling with these, there are paintings by some of Hockney’s predecessors from Bradford. One of these was Richard Eurich (1903-1992), the son of Dr Frederick William Eurich (1867-1945). Dr Eurich, who arrived in Bradford from Chemnitz (in Germany) aged seven, pioneered a method of cleaning wool so that it became free of the deadly anthrax spores that had taken the lives of many wool workers in Bradford. His son Richard studied at Bradford School for Arts and Crafts, where Hockney also studied later.

Sir William Rothenstein (1872-1945) attended Bradford Grammar School, where both Richard Eurich and, later, David Hockney were pupils. He studied art at the Slade School in London. He became a war artist in WW1. At least one of his war paintings was on display. Rothenstein was a son of Moritz Rothenstein, one of several Jewish entrepreneurs who came from Germany to Bradford in the mid-19thcentury. These entrepreneurs played important roles in promoting the city’s textile industry. William’s painting “Carrying the Law” has a particularly Jewish theme. In the 1930s, William, by then in London, hosted the Indian Nobel Prize winner Rabindranath Tagore, who dedicated his collection of poems “Gitanjali” to him.

By William Rothenstein

This brings me to something that I really liked about the Gallery. The paintings (and stained-glass) by European artists, both well-known and not so famous, are hung side-by-side with works by artists with South Asian heritage. This is done so successfully that one does not feel that there is any cultural clashing between them. It made me think how wonderful it would be if people of different origins could coexist so harmoniously.

By Sylvat Aziz

The South Asian artists, to mention but a few, include Jamini Roy (whose pictures we did not see on display during our visit), Salima Hashmi, Arpana Kaur, Sylvat Aziz, and Gurminder Sikand. In addition to these paintings, we saw one Indian film poster on display. Just opposite the main entrance on the ground floor, there is a reflective sculpture by Anish Kapoor.

By Anish Kapoor

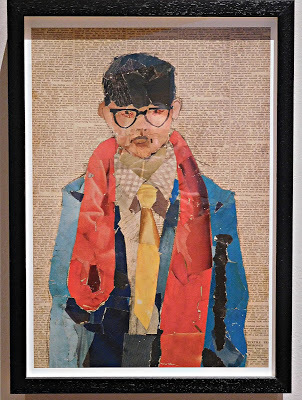

The new Hockney Gallery is itself a masterpiece of gallery curation. It contains some of Hockney’s earliest works done in the 1950s. These works, somewhat more conventional than his later creations, show him as a highly skilled draughtsman and artist. They portray his home town beautifully. The gallery also contains some of Hockney’s more current work, including a series of paintings done during one of his visits to his native Yorkshire. There is also one of his famous swimming pool pictures. The gallery features a ‘recreation’ of one of Hockney’s studios. This display includes a couple of the artist’s sketch books and pads. I was particularly intrigued by two publications on display, which were illustrated by Hockney: one was a Bradford telephone directory, and the other a guide book to Bradford.

David Hockney: Self-portrait (1954)

Our visit to the Cartwright Gallery was enjoyable, and left me thinking that even if one saw nothing else in Yorkshire, this place is a ‘must’.

The town of Saltaire is a short bus ride from Lister Park, and another mecca for lovers of Hockney’s art. Before 1851, this place did not exist. It was built by a benevolent industrialist Sir Titus Salt (1803-1876) as a model village for the workers in his textile factory, Salts Mill, which neighbours it. The place’s name derives from Sir Titus’s surname and the River Aire, which runs close to the mill. The mill is separated from it by the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. Saltaire is a well-preserved ensemble of Victorian buildings. It has been designated a ‘UNESCO World Heritage Site’.

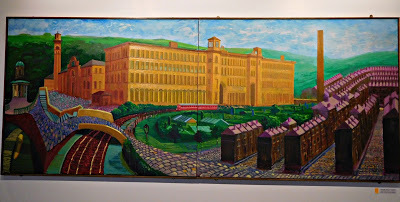

Salts Mill painted by David Hockney

Hockney lovers might focus only on the enormous Salts Mill, but this is a mistake because it would mean missing the fascinating little town, an industrial forerunner of ‘idyllic arcadian’ garden suburbs and cities, such as those in north-west London, Letchworth, and Welwyn. It is also an antecedent of garden cities designed to house factory workers such as: the Bata village at East Tilbury; Zlin in the Czech Republic; and Zelenograd (i.e. ‘green city’) near Moscow in Russia.

Victoria Street leads down towards the railway, the mill, the canal, and the river. The upper section is lined with attractive stone buildings on one side. On the other side, there is a rectangular green space, Alexandra Square, surrounded by more buildings, alms-houses. The former ‘Sir Titus Salts Hospital’ (dated 1868) stands where Victoria and Saltaire Roads cross each other.

Further down the hill, we reach the Salt Building, which is marked as ‘schools’ on an 1889 map. It was a ‘factory school’. Mill owners were obliged by laws (passed after 1833) to provide their child-workers with education. Now a part of Shipley College, it still serves an educational purpose.

Opposite this architecturally whimsical building, there is a larger one set back from the road. With two storeys of windows topped with circular arches and a grandiose central doorway surmounted by a tower, this is Victoria Hall. This was completed in 1871 for Sir Titus to the designs of Lockwood and Mawson. Originally, it was an educational institute, but now its grand hall and other rooms are also used for special occasions such as weddings.

The Salts Mill stands almost at the bottom of Victoria Street. Ignore this for the moment, and enter Albert Terrace. But, before doing so, you should take a look at the Saltaire United Reform Church, which stands in its own grounds close to the canal. This interesting Italianate building with a circular tower mounted on a circle of Corinthian pillars was built for Sir Titus in 1859, designed by Lockwood and Mawson.

Albert Terrace runs along the lower ends of several steep streets where the mill employees lived in houses of different sizes according to their inhabitant’s ranking in the firm’s hierarchy. The streets are separated by the backyards of the buildings on them, and between them the narrow back alleyways, which are now crowded with ‘wheelie-bins’ used for placing domestic refuse.

Some of the buildings on these streets are taller than their neighbours. These housed lower-paid workers. Those houses between them, which have small front gardens, were homes to foremen and supervisors. Senior members of the firm had larger houses with bigger front gardens.

On Titus Street, parallel to Albert Terrace but at a higher altitude, there are small terraced dwellings without front gardens whose front doors open straight out onto the pavement. These residences were the homes of the lowest paid workers and their families. Although different classes of mill employees were allotted different kinds of houses, all of them from the humblest to the highest lived together in close proximity. It is interesting that the founders of Hampstead Garden Suburb in North London, where I grew up, tried to achieve the same social mixing. I do not believe that it was ever achieved there.

The school on Albert Road, now a primary school, has been present since 1893 if not before. Near the south end of Albert Road at its meeting with Saltaire Road, there is a stone building whose two sets of enormous doors are surmounted with triangular pediments bearing weather-worn coats of arms. Now a restaurant, this was formerly a tramway depot.

The Salts Mill, the former textile factory, is now home to a huge exhibition of works by David Hockney. This is arranged on three floors of the building in what were once huge halls where William Blake’s ‘dark satanic mills’ churned out the materials that made Bradford prosperous. Actually, this particular mill seems to have been quite well-lit.

On the lowest floor and the one above it, the walls are hung with works by Hockney, mostly prints, but, also some paintings. Much of the floorspace in the ground floor gallery is filled with tables containing merchandise for sale, including, appropriately, artists’ materials. On the second floor, there is a vast bookshop, also lined with works by Hockney.

The uppermost floor is a huge exhibition space without merchandise. Its walls were lined with Hockney’s pictures. They can be seen at their very best in this spacious hall supported by cast-iron pillars. This gallery leads to a café, where ‘light bites’ and drinks are available.

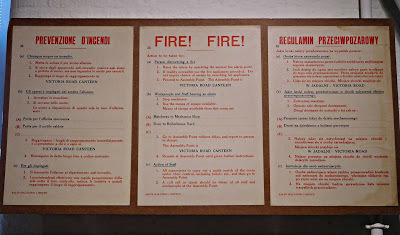

Beyond the café, there is a permanent display of objects relating to the history of Salt Mill. These include items such as: old factory equipment; examples of textiles produced; a dental chair from the factory’s own dental clinic; and a small fire-engine. On one wall there was an old notice informing workers what to do if fire broke out. This was printed in English, Italian, and Polish. The factory closed in 1986, long before Poland joined the European Union and the recent influx of working people from Poland. The existence of the Polish instructions suggests that even in the 1980s Bradford had a significant Polish population. According to an article published on a BBC website (in September 2014): “In the 1940s it was immigrants from Poland who came to Bradford. They viewed themselves as political émigrés so it was important to maintain a national identity, traditional ideas, values and customs, all of which were being suppressed in their homeland which was under Nazi rule.”

Some decorative porcelain in the museum bears the crest of the Salts family. It includes an alpaca, whose wool, combined with other animal’s fleeces, was an important contribution to the prosperity of Sir Titus’s family. Near this display of porcelain, there is a cleverly devised portrait of Sir Titus made using fabric from which pieces have been removed selectively to produce the image.

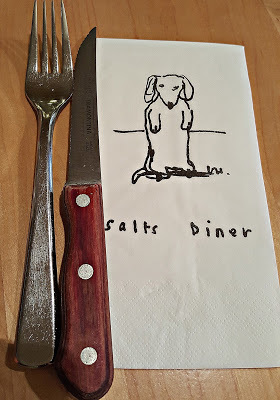

We did not eat at the café, but at Salts Diner on the floor with the gallery/bookshop. The Diner’s menu cards and napkins are designed by David Hockney. The diner’s walls are lined with the artist’s works. We ordered two dishes: a smoked chicken with mango salad, and steak with chips and Béarnaise Sauce. We washed these down with a lovely beer specially created for the Saltaire Diner. Without hesitation, I can say that this was the best quality food that we have ever eaten in a café or restaurant attached to a museum or gallery.

Napkin with a drawing by David Hockney

Although there is no shortage of works by Hockney at the Salts Mill, I much preferred the smaller but exquisitely curated gallery of his art at nearby Cartwright Hall. However, a Hockney aficionado will be missing a great experience by not making the trip ‘up north’ to see the Hockney exhibits just outside Bradford.

READ AND ENJOY BOOKS BY

ADAM YAMEYVisit: http://www.adamyamey.com

October 11, 2017

FRESTONIA lives again!

Overshadowed by the charred remains of Grenfell Tower (built in 1974 as part of the Lancaster West Estate), Freston Road runs close to Latymer Road Underground Station. During the early 1970s when tower blocks, such as the ill-fated Grenfell, were being built, Freston Road was a jumble of run-down, mostly vacant, Victorian dwellings.

Squatters moved into these empty houses in the early 1970s. When the Greater London Council (‘GLC’) wanted to redevelop the area that included Freston Road, all of the residents adopted the surname ‘Bramley’, so that the GLC would be faced with housing a very large family. When the Council threatened compulsory eviction at a meeting attended by more than 200 residents, the residents under threat declared that the area around Freston road should become an independent republic, separate from the UK. Thus, was born the ‘The Republic of Frestonia’ in 1977.

The Republic, which applied for membership of both the UN and the European Economic Community, survived for several years. Life in the ‘Republic’ was recorded in photographs by the photographer Tony Sleep. An exhibition of his beautiful photographs of life in Frestonia opened this evening (11th October 2017) at the Frestonia Gallery at 2 Olaf Street, W11 4BE. It will continue until 10th of November. The gallery is housed within the Peoples Palace (built 1902), which is almost the only remaining building amongst those which existed during the lifetime of the Republic.

In addition to the wonderfully composed black and white photographs, there are also display cases containing documents relating to the Republic. These include contemporaneous press-cuttings, the application to the UN, and special postage stamps issued by the Republic. The exhibition is a worthy homage to a fascinating episode in London’s complex history.

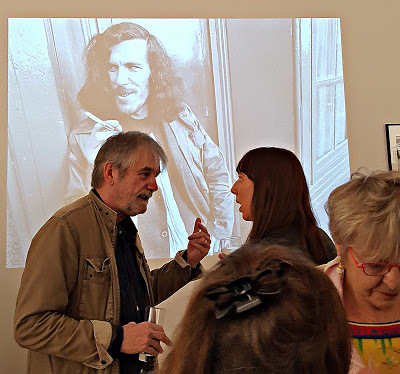

Tony Sleep with one of his photos projected behind him

The opening of the exhibition was a very special occasion. Not only was Tony Sleep present, but also some of the now ageing inhabitants the short-lived Republic.

This is an exhibition well worth visiting – not to be missed.

See also: https://londonadam.travellerspoint.com/32/

Now, it's time to read a book by ADAM YAMEY:

visit: http://www.adamyamey.com

October 8, 2017

AN ALBANIAN CONDUCTOR IN LONDON

CONCERT 7th OCT 2017 AT ST STEPHENS CHURCH SW7 4RL

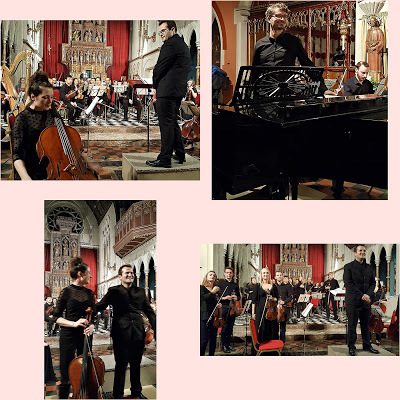

Last night (7th Oct 2017), I attended an orchestral concert performed by the London City Philharmonic, an orchestra whose players come from all over the world. The conductor was the Albanian Olsi Qinami, a founder of the orchestra. The programme, “Tales from the East”, consisted of music by eastern European composers with one exception.

The concert began with a sensitive rendering of Antonin Dvorak’s “Slavonic Dances”. This was followed by Max Bruch’s “Kol Nidrei”, Adagio on Hebrew Melodies”. Bruch was not an Eastern European, having been born a Protestant in Cologne (in 1838). He was fond of using ‘exotic’ themes in his compositions. The piece for cello soloist and orchestra, which we heard last night looks eastwards in a romantic way at a prayer of the Ashkenazi Jews, which is recited at Yom Kippur. The cellist, Alexandra Fletcher, a Londoner, played beautifully.

These two well-known pieces were followed by two compositions, which deserve to be better-known. The first was a piano concerto (“Concerto for piano and orchestra in one movement”) by Fatos Lumani (born 1983), a Professor at the State University of Tetova in Macedonia. The soloist in this powerful, invigorating piece was Shkelzen Baftiari, an Albanian Macedonian who lives in Skopje (Macedonia). His playing of this complex composition was masterful. The orchestra accompanied him skilfully, seemingly with great ease given how difficult this piece is to perform.

The evening continued with an orchestral piece, “Arbereshes Sime”, by the Albanian composer Gerti Druga. He was born in Kuçovë (Albania) in 1986. The first part of this beautiful composition was based on the melody of a song sung by the Arbëreshë people, descendants of Albanians who escaped from the Ottomans in the 15thcentury and settled in Italy, where, to this day, they speak an archaic form of Albanian and maintain the traditions of their ancestors. During second half of the piece, the music livened up considerably. It reminded me, and I mean this in a positive way, of the best of the stirring propagandistic music that the former Communist regimes used to inspire their people. The orchestra was accompanied by Shkelzen Baftiari on the piano and featured solos by the orchestra’s leader, the Finnish-born violinist Alina Hiltunen. I was not alone in enjoying this piece; the audience loved it.

After the interval, the orchestra, as always directed skilfully by Olsi Qinami, gave a great performance of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony Number 4. Lasting just under an hour, the orchestra never flagged. Their account of this moving piece was exhilarating.

If you did not attend this concert, I feel sorry for you because you missed a great musical experience!

ENJOY BOOKS WRITTEN BY ADAM YAMEYVISIT: http://www.adamyamey.com

September 5, 2017

THE KING OF THE ZULUS STAYED HERE

Melbury Road: Tower House: gargoyle

Roque’s map drawn in the early 1740s shows that Kensington was then a small village separated by open country (Hyde Park and the grounds of Kensington Palace from the western edge of London (marked by the present Park Lane). It lay on The Great West Road, a turnpike road leading from the city to Brentford and further west (e.g. Bath and Bristol). Kensington was separated from the next settlement, Hammersmith, by agricultural land with very few buildings.

The name ‘Kensington’ appeared in the Domesday Book as ‘Chenisitum’, which is based on the name of a person who held a manor in Huith (Somerset) during the reign of Edward the Confessor (ruled 1042-1066). During the 17th century, large houses such as Kensington Palace and the now demolished Campden and Holland Houses were established in Kensington and needed people to service and protect them. This and the fact that it was on the busy Great West Road must have influenced the growth and importance of the village. Being close to the ‘Great Wen’ as William Cobbett (1763-1835), a great advocate of the countryside, rudely described London, yet separated from it (as was also Hampstead), Kensington attracted people, including many artists, to live there, especially in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. During the 18th century, reaching Kensington from London, only four miles from the city’s Temple Bar, was not without danger as highwaymen operated in Hyde Park.

Mosaic by Fox schoolkids Church Str Kensington

This exploration begins (close to Notting Hill Gate Tube station) at the northern end of Church Street, which in the 1740s led from the Kensington Gravel Pits (now, Notting Hill Gate) that lined the northern edge of Bayswater to the centre of Kensington Village. Today, the road follows the same course as it did in the 18th century. Close to the Post Office and the Old Swan Pub (apparently, Christopher Wren and King William III drunk in one of its earlier reincarnations), there is an alleyway decorated with tiling designed by pupils of the nearby Fox Primary School.

Clementi lived here Kensington Church Str

Churchill Arms Kensington Church Str

Just south of some of the numerous antique dealers’ shops that line Church Street, there is an 18th century house where the Italian-born composer Muzio Clementi (1752-1832) lived for many years. Nearby, is the colourfully adorned Churchill Arms pub, which was established in the mid-18th century. It offers Thai food. A tree on the corner of Church Street and Berkeley Gardens is labelled with a plaque stating that it came from Kensington in Maryland (USA) in 1952.

Berkely Gardens

A large brick-built block of flats on Sheffield Terrace is named Campden House. This and Campden House Close, which leads off Hornton Street, are reminders that they were built on the extensive grounds of the former Campden House, which was built about 1612 (see: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/surv...). An illustration published by The Reverend Lyson in 1795 shows that this was a fine building rivalling places such as Hatfield House. Sadly, it was demolished in about 1900.

Campden House Close

Sibelius in Gloucester Walk Kensington

Corner Hornton Str and Holland Str

Charles Stanford lived here Holland Str

Corner Hornton and Holland Streets

Just before Hornton Street reaches the Town Hall and Library, it meets Holland Street. A small building on the corner was once the home of the composer Charles Stanford (1852-1924) between 1894 and 1916. Its drain pipe is embellished with two small bas-reliefs of animals. I wonder whether he ever bumped into the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius (1865-1957), who lived close by in Gloucester Walk during 1909. Opposite Stanford’s house, stands number 54 Hornton Street, which used to be number 43. The ‘43’ remains on the building, but has been struck out with a line.

Drayson Mews

Elephant and Castle Holland Street

Gordon Place

Holland Street is full of treats. Number 37 was home to the lesbian novelist Radclyffe Hall (1880-1943) between 1924 and 1929. It is worth wandering along the picturesque cobbled Drayson Mews before returning to Holland Street. The popular Victorian Elephant and Castle pub is opposite a delightful cul-de-sac Gordon Place, which is overhung with vegetation growing in the gardens lining it. The pub bears a large picture of an elephant with a castle on its back. This closely resembles part of the coat of arms of the Worshipful Company of Cutlers (see: http://www.cutlerslondon.co.uk/compan...).

Old houses, number 12 Holland Street

The artist Walter Crane (1845-1915), who collaborated with William Morris, lived in number 13 Holland Street from 1892 onwards. This house is opposite number 12, the street’s oldest surviving building, which was built about 1730. It was built on the site of a ‘dissenting house’ built in 1725 (see: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/surv...).

Carmel Court

Carmelite Monastery

Carmelite Church Kensington Church Street

Carmelite Church Kensington Church Street

The narrow partly covered Carmel Court next to number 12 leads to the south side Catholic Carmelite monastery (Victorian) and its newer Church (built between 1954 to 1959, and designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott [1880-1960]). The name of its neighbour on Church Street, Newton Court, recalls that in 1725 the scientist Isaac Newton (1643-1727) lived somewhere close-by (see: http://www.isaacnewton.org.uk/london/...). Returning via Church Street to Holland Street, there is a Lebanese restaurant on the corner. This is housed in what was the Catherine Wheel pub until 2003.

The former Catherine Wheel pub on Kensington Church Street

St Mary Abbots

St Mary Abbots Kensington

St Mary Abbots Kensington

St Mary Abbots Kensington

The lower end of Church Street is dominated by the tall spire of St Mary Abbots Church. The present building, a Victorian gothic structure, was built in the early 1870s to the designs of Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878; grandfather of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott), who died in Kensington. A sort of cloister leads from the war memorial and flower stall at the corner of Church Street to the church’s western entrance. The church’s interior is grand but not exceptional.

St Mary Abbots School Kensington

St Mary Abbots School Kensington

St Mary Abbots Gardens

To the South of the path leading to the church, there is a Victorian gothic school building, part of St Mary Abbotts Primary School. This school was founded nearby in 1645 (see: http://www.sma.rbkc.sch.uk/history-of...). In about 1709, it was housed in two buildings on the High Street, where later the old Kensington Town Hall was built (it was demolished in 1982, and replaced by a non-descript newer version on Hornton Street). High on the wall of the Victorian school building, there are two sculptured figures wearing blue clothing, a boy and a girl. These used to face the High Street on the 18th century building. The boy holds a scroll with the words: “I was naked and ye clothed me” (from Matthew in the New Testament). The school continues to thrive today.

Former public library Ken High Str

Walk through the peaceful St Mary Abbots Gardens – once a burial ground (and in the 1930s, also the site of a coroner’s court), and you will soon reach a wonderful Victorian gothic/Tudor building on the busy High Street. Faced with red bricks and white stonework, this was built as the local ‘Vestry Hall’ in 1852. It was designed by James Broadbridge. From 1889 to 1960, it housed Kensington Central Library, which is now located in a newer, less decorous, building in Hornton Street. The former Vestry Hall is now home to an Iranian bank. Incidentally, there are many Iranians living in Kensington.

Barkers High Str Kensington

Derry and Toms building High Str Kensington

Lovers of art-deco architecture need only turn their backs on the old Vestry Hall to behold two perfect examples of that style. They used to house two department stores: Derry and Toms built in 1933; and Barker’s (built in the 1930s). Barker’s took over its rival Derry and Tom’s in 1920. Both replaced older buildings, were designed by Bernard George (1894-1964), and are covered with a great variety of art-deco ornamentations. The Derry and Toms building has a wonderful roof garden,

Barkers High Str Kensington

Barkers High Str Kensington

Barkers High Str Kensington

Derry and Toms building High Str Kensington

The Kensington Roof Gardens (opened 1938) has a restaurant open to the public. In the early 1970s, the Derry and Toms building briefly housed the then extremely trendy Biba store, the inspiration of Polish-born Barbara Hulanicki. Now, there are various retail stores using the ground floors of these two buildings. The upper floors of Barker’s contain the offices of two newspapers: The Evening Standard, and The Daily Mail. A short street, Derry Street, running between these two buildings leads into Kensington Square.

Kensington Square Gardens

With a private garden in its centre, Kensington Square is surrounded by fascinating old buildings (for a history and guide, see: https://www.rbkc.gov.uk/sites/default...). The setting-out and development of the square began in 1685, when it was named ‘Kings Square’ in honour of the ill-fated James II, who had been crowned that year. In those early days, this urban square was surrounded by countryside – gardens and fields (see: “London” by N Pevsner, publ. 1952). With the arrival of the Royal Court at Kensington Palace in the 17th century (King William III, who ruled from 1689 to 1702, suffered from asthma, and needed somewhere where the air did not aggravate his condition – see: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/surv...), the square became one of the most fashionable places to live in England, but this changed when George III (ruled 1760-1820) moved the Court away from Kensington. After 1760, the square was mostly abandoned, and remained unoccupied until the beginning of the 19th century. Nowadays, its desirability as a living place for the well-off has been firmly restored.

Edward Burne Jones lived in Kensington Sq

The attractive garden in its centre is adorned with small neo-classical gazebo. The houses surrounding the garden have housed many famous people. Number 40 has a 19th century façade, which conceals an earlier one. It was the home of the pathologist Sir John Simon (1816-1904), a pioneer of public health. Between 1864 and 1867, the painter Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) lived at number 41, which has Regency features as well as newer upper floors.

11 and 12 Kensington Square

11 Kensington Sq Mazarin Herring and Talleyrand might have lived here

At the south-east corner of the square, the semi-detached numbers 11 and 12 were built between 1693 and 1702. The attractive shell-shape above the front door of number 11 bears the words: “Duchess of Mazarin 1692-8, Archbishop Herring 1737, Talleyrand 1792-4”. Although it is tempting to believe that these celebrated people lived here, this was probably not the case. The Duchess, a mistress of Charles II, is not thought to have ever lived in the square. Talleyrand (1754-1838) did stay in the square, maybe or maybe not in this house, which was then occupied by a Frenchman, Monsieur Defoeu. As for Herring (1693-1757), he did live in the square but not at number 11. So, whoever put up the wording had a sense of history, but was lacking in accuracy.

Kensington Court Mews

TS Eliot lived here

Joan Sims lived here on Thackeray Street

Thackeray Street leads to Kensington Court, where a picturesque courtyard, named Kensington Court Mews, is surrounded by former stables. South of this, its neighbour, a 19th century brick apartment block, Kensington Court Gardens, was the home and place of death of the poet TS Eliot (1888-1965). Returning to the square via Thackeray Street, we pass Esmond Court (named after one of Thackeray’s novels), where the actress, best-known for her roles in the “Carry-On” films, Joan Sims (1930-2001) lived.

John Stuart Mills 18 Kensington Sq

Maria Assumpta Church Kensington Sq

Maria Assumpta Church Kensington Sq

Heythrop College Kensington Sq

The philosopher John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) wrote important books on logic and Political Economy while living in number 18 Kensington Square (built in the 1680s) between 1837 and 1851. Close by, the row of old buildings interrupted by a newer building, the Victorian gothic Roman Catholic Maria Assumpta Church, which was built in 1875 to the designs of George Goldie (1828-1887), TG Jackson (1835-1924) and Richard Norman Shaw (1831-1912). George Goldie also designed the church’s neighbouring convent buildings, which are now adorned by a ground floor gallery consisting of six large windows and the main entrance door, which was added in the 1920s. The former convent is now the home of the University of London’s Heythrop College. Specialising in the study of philosophy and religion, the college was incorporated into the university in 1971. However, amongst all the university’s constituent colleges, Heythrop goes back the furthest, having been founded by the Jesuits in 1614. Founded in Belgium, it moved to England during the French Revolutionary Wars at the end of the 18th century.

Kensington Sq West side

30 Kensington Sq Hoare's House

Hoare's arms on 30 Kensington Square

The west side of the square presents a fine set of facades dating back to when the square was first established. Each of the buildings is of great interest, but the one which caught my attention is number 30, which is adorned with double-headed eagles, a symbol used by, to mention but a few: the Hittites, the Seljuk Turks, the Holy Roman Empire, Mysore State, the Russians, the Serbians, and the Albanians. The bicephalic birds on number 30 relate to none of these, but, instead, to the Land Tax Commissioner Charles Augustus Hoare (see: “A Collection of the Public General Statutes passed in the Sixth and Seventh Year of the Reign … of King William the Fourth 1836”) of the Hoare family of bankers. He bought the house in about 1820, and died in 1862 (see: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/surv...).

33 Kensington Sq Mrs Patrick Campbell lived here

Number 33 was built in the early 1730s. Between 1900 and 1918, the actress Mrs Patrick Campbell (1865-1940), who was born in Kensington, lived there. She is said to have inspired some of the plays written by George Bernard Shaw. From Kensington Square, it is a short walk to High Street Kensington Station, which is entered via a shopping arcade that leads to a covered octagonal entrance area decorated with floral bas-reliefs, suggestive of the era of art-nouveau.

High Street Ken Station

Cafe Nero Wrights Lane

At the corner of Wrights Lane, there is a branch of the Caffe Nero chain, which is housed in a modern, glass-clad narrow wedge-shaped building. Further down Wrights Lane, there is a charming old-fashioned tea shop, The Muffin Man, which serves excellent reasonably priced snacks and light meals. Before reaching this eatery, take a detour to visit Iverna Gardens.

St Sarkis Iverna Gdns

At the southern end of the small square, there is the Armenian Church of St Sarkis, which was built in 1922-23 with money supplied by the Gulbenkian family. Built to resemble typical traditional churches in Armenia, it was designed by Arthur Davis (1878-1951), who was born in, and died in Kensington.

Our Lady of Victories

Our Lady of Victories

Mosaics outside Our Lady of Victories

Much of the High Street is occupied by shops housed in unexceptional buildings. To the west of most of these, stands the Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady of Victories. Its entrance screen on the High Street was designed by Joseph Goldie (1882–1953). It served as the entrance to a church that was destroyed by bombing in WW2. The present church was built in 1957, designed by Adrian Gilbert Scott (1882-1963), brother of Sir Giles (see above).

Old Odeon cinema High Str Ken

Beyond the north end of Earls Court Road, two buildings are currently behind builders’ hoardings. One, the old post-office, will probably be demolished, but the other, an Odeon cinema, is to have its impressive neo-classical art-deco façade preserved, but its interior will be re-built. Originally named the ‘Kensington Kinema’, it was opened in 1926. It was closed in 2015 (see: http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/1...).

Edwardes Square east side

Scarsdale Tavern Edwardes Sq

Edwardes Sq Sir William Rothenstein lived here

Further west, a narrow road leads from the High Street into Edwardes Square. This Georgian square was laid out by a Frenchman, the architect Louis Léon Changeur, between 1811 and 1820, and named after William Edwardes (1777-1852), the 2nd Lord Kensington, who owned the land which it occupies (see: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/surv...). At the south-east corner of the square, there is an almost-hidden pub, the Scarsdale Tavern, which was established in 1867. Opposite it, is the two-storey house where the painter and writer Sir William Rothenstein (1872-1945) lived between 1899 and 1902. Like so many other London Squares, this one has a centrally located private garden. At its southern edge, there is a neo-classical pavilion, now called ‘The Grecian Temple’, and still used by the head gardener. The garden’s paths were laid out by an Italian artist Agostino Aglio (1777-1857), who, having arrived in the UK in 1803 to assist the architect William Wilkins, lived in the square between 1814 and 1820.

The Grecian Temple Edwardes Sq

Edwardes Square Studios

Edwardes Sq West side

Edwardes Square Studios opposite the Temple was home to artists including Henry Justice Ford and Clifford Bax. Better-known today than these two was the comedian Frankie Howerd (1917-1992), who also lived on the square from 1966 until his death. The north-western corner of the square leads back into the High Street. Immediately west of this, there is a row of three neighbouring Iranian food stores and an Iranian restaurant. The presence of these is symptomatic of the many emigrants from Iran, who have settled in Kensington.

Iranian shops and restaurant Hig Str Ken

2 St Mary Abbots Place

9 St Mary Abbots Place White Eagle Lodge

Just west of the Iranian establishments, there is a cul-de-sac called St Mary Abbots Place. The façade of number 2 (part of a building called Warwick Close) is adorned with wooden carvings that have an art-nouveau motif. Above an entrance to number 9, there is a bas-relief of an eagle. Until recently, this building housed a branch of ‘The White Eagle Lodge’, a spiritual organisation founded in Britain in 1936 (see: https://www.whiteagle.org/). At the end of the street, there is a large brick building with a neo-Tudor appearance. This was built for the painter Sir William Llewellyn (1858-1941).

St Mary Abbots Place White Eagle Lodge and Llewellen's brick house

St Mary Abbots Place

GK Chesterton lived on Warwick Gardens

At the northern end of Warwick Gardens, a house (number 11) bears a plaque celebrating that the writer GK Chesterton (1874-1936) lived in it. He was born in Kensington.

Column on Warwick Gdns

Column on Warwick Gdns

Opposite the house on an island around which traffic flows, there is a tall pink stone column, surrounded by palms and surmounted by an urn. It is dedicated to the memory of Queen Victoria. Dated 1904, it was designed by HL Florence, who was President of The Architectural association between 1878 and ’79.

47 Addison Road

Olympia from Napier Road

The continuation of Warwick Gardens north of the High Street is called ‘Addison Gardens’. The west side of this is lined by some 19th century houses with neo-gothic features. Napier Road leads off Addison towards, but does not reach, the Olympia exhibition halls. At the corner where the two roads meet, there is a large house, number 49 Addison Road.

49 Addison Rd

49 Addison Rd. W14 Crest of Herbert Schmalz

Behind it, and easily visible from Napier Road, this house has an extension with a huge ornately framed north-facing window. Above this, there is the date “1894” and a figure holding an artist’s palate overlaid with the intertwined initials “HS”. And below that, a motto reads in German “Strebe vorwaerts” (i.e. strive ahead). This was the studio built for the pre-Raphaelite painter Herbert Gustave Schmalz (1856-1935), who was a friend of the painters William Holman Hunt and Frederic Leighton (see below).

St Barnabas Addison Road

The delicate-looking 19th century gothic church of St Barnabas stands on Addison Road just north of Melbury Road. This was designed by Lewis Vulliamy (1791-1871), and built by 1829. Prior to its existence, the only parish church in Kensington was St Mary Abbots. St Barnabas was built to serve people living in the new housing that was rapidly covering the land to the west of the centre of Kensington (see: http://www.stbk.org.uk/about-us/#about). It never had a graveyard because by the 1820s sanitary authorities were discouraging the placing of these so close to the centre of London.

Sir Hamo Thornycroft lived here in Melbury Rd

Melbury Road is lined with grand houses built between 1860 and 1905, some of them containing large artists’ studios. Many well-known artists, members of the ‘Holland Park Circle’, have lived and worked in this street and Holland Park Road that leads off it. A plaque next to a large north facing studio window on number 2 Melbury Road commemorates that English sculptor Hamo Thornycroft (1850-1925) worked here.

8 Melbury Rd

The large number 9 is in ‘Queen Anne style’, and was built in 1880. Opposite it, number 8, designed by Richard Norman Shaw, with north-facing studios was built for the painter Marcus Stone (1840-1921). In later years, this house, now converted into flats, was from 1951-1971 the home of the film director (who made many films with Emeric Pressburger including “Black Narcissus” and “The Red Shoes”), Michael Powell (1905-1990).

Tower House Melbury Road

Tower HouseMelbury Road