Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 120

April 3, 2014

The Invention of News

At a time when digital media is transforming the way news is delivered–and by whom– Andrew Pettegree offers a reminder that newspapers too were once a revolutionary form of delivering information. In The Invention of News: How The World Came To Know About Itself, Pettegree looks at the changing definition, use, control, and distribution of the news from the medieval world to the age of revolution.

At a time when digital media is transforming the way news is delivered–and by whom– Andrew Pettegree offers a reminder that newspapers too were once a revolutionary form of delivering information. In The Invention of News: How The World Came To Know About Itself, Pettegree looks at the changing definition, use, control, and distribution of the news from the medieval world to the age of revolution.

Building on his previous work in the ground-breaking The Book in the Renaissance,* Pettegree demonstrates how access to news became increasingly widespread, moving from private information networks run by medieval elites, through sixteenth century news pamphlets and news singers, to the newspapers of the eighteenth century. He looks at the development of postal systems, private couriers and the printing press. He considers the importance of the introduction of paper, the rise of coffee shops and the growth of a literate middle class. He discusses the roles played by news pamphlets in the Reformation and by newspapers in the American and French Revolutions.

Some of the most interesting sections of The Invention of News deal not with the development of new media, but the creation of new audiences. Technology often outpaced demand. Early printers, finding the traditional market for large books would not keep them solvent, created new markets for more ephemeral products. The first newspapers were bewildering to audiences accustomed to news pamphlets that told a single story from beginning to end. Perhaps, at some level, the medium is the message.

* Also well worth reading. Printing and the Protestant Reformation are more closely linked than you might think.

A version of this review previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

March 31, 2014

Foyle’s War

History buff-ery can lead you to unexpected places. Recently it’s led My Own True Love and I to our living room in front of the television, where we are totally absorbed in the BBC television series Foyle’s War.* It’s a police procedural set during World War II in the town of Hastings** on the southeast coast of England. The main character, detective chief inspector Christopher Foyle, would rather be in the armed services doing his part but his superiors feel he will do more good maintaining order along the coast.

The care with historical detail in the series is impressive,*** but the choice of period is more than set-dressing. The first season is overshadowed by the fear of German invasion. Subsequent seasons follow the course of the war. The murders in each episode derive directly from wartime conditions in Britain.

Even more interesting, from my perspective, is the representation of wartime British society. Patriots and heroes are shown side by side with Nazi sympathizers, rabid anti-Semites, draft dodgers, profiteers, hoarders, and soldiers irreparably damaged by their experience at the front. Innocent German refugees suffer at the hands of Britons whose patriotism has hardened into intolerance and hatred. Soldiers treat women badly. Men in important positions assume their value to the war effort exempts them from the rule of law. The government tries to cover up failures. The memory of World War I is never far away–something we often forget. This is not a simple picture of gallant little England standing alone against the Nazis. In many ways, it makes the instances of bravery, generosity and justice that appear in each episode more impressive.

We just finished season 5, which centers on the announcement of the German surrender. It will be interesting to see if the historical interest of the series holds as Foyle and his team move into the Cold War.

Don’t touch that dial.

* We are not cutting edge television viewers. The first season of Foyle’s War aired in 2002; season 9 is now in production.

** As in the Battle of Hastings–a subtle reminder that the threat of invasion from continental Europe is a pervasive element of British history, from the Romans onwards. No island is an island.

*** The only note that they don’t quite hit is the issue of scarcity. Characters talk about coupons and rations. In one episode, members of the police force drool over food being held as evidence in a profiteering case. In another, the detective team enjoys the bounty available at an agricultural worker’s boarding house. But you never get the feeling that people are never really warm, that clothing is patched and remade to make it last, or that they are hungry. If you want to get a good since of how pinched the average Briton was during the war, I suggest you read letters or popular fiction written during or just after the war. Off the top of my head, I would suggest Helene Hanff’s 84 Charing Cross Road, Angell Thirkell’s novels set during the war (pure fluff but very clear on the scarcity), or Agatha Christie.

March 21, 2014

How Paris Became Paris

In How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City, historian Joan DeJean (The Age of Comfort) argues that the real transformation occurred two centuries earlier, when Henri IV set out to rebuild a city that had been ravaged by Catholic and Protestant alike during the thirty-six years of the Wars of Religion. In 1597, wolves roamed freely in the French capital; by 1700, Paris was synonymous with culture, glamour and fashion.

In How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City, historian Joan DeJean (The Age of Comfort) argues that the real transformation occurred two centuries earlier, when Henri IV set out to rebuild a city that had been ravaged by Catholic and Protestant alike during the thirty-six years of the Wars of Religion. In 1597, wolves roamed freely in the French capital; by 1700, Paris was synonymous with culture, glamour and fashion.

Beginning with the building of the Pont Neuf (literally, the New Bridge), DeJean tells the story of a hundred years of royal vision, private funding, innovative real estate development and public planning. She also looks at how physical changes to the city created new behaviors, new institutions, and new problems. Many of the things that we think of as typically urban first appeared at this time: from public transportation and sidewalks to traffic jams and tourists. (Not the same thing as pilgrims.) Other changes are less familiar: new public spaces in which to promenade led to the new crime of cloak-snatching.

DeJean is also concerned with more than just seventeenth century urban renewal. Using a range of sources including contemporary guidebooks, plays and travel accounts, she explores how the city’s image was reinvented –creating a fantasy of Paris as what Claude Monet would later describe as “that dizzying place.”

March 18, 2014

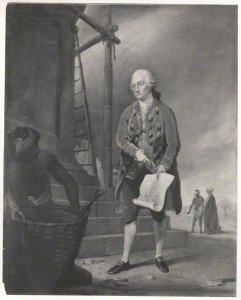

The Black Hole of Calcutta

In mid-eighteenth century India, power was up for grabs. The Mughal dynasty was in decay. Smaller regional powers flourished. European trading companies, which held their trading privileges at the discretion of Indian rulers, were constantly looking for a way to get an edge. The British and French East India Companies, in particular, maintained private armies with which to defend themselves–usually against each other.

In 1756, the British East India Company became involved in a dispute with the new Nawab of Bengal, twenty-six-year-old Siraj-ud-duala. The young Nawab looked on the growth of the British settlement at Calcutta with both greed and suspicion. When he learned that the British merchants, in anticipation of war with France, had begun to expand their fortifications without his permission, he marched on Calcutta with 30,000 foot, 20,000 horse, 400 trained elephants and 80 cannon. The city was defended by a small, badly trained, force of soldiers and militia. Siraj-ud-daula attacked early on June 20.Anyone who could escaped down river by boat in a disorganized retreat. Those who had been unable to escape surrendered by mid-day and spent the night in the the Black Hole, a cell in which the British locked up drunken soldiers. The next day, the survivors were forced to leave Calcutta and made their way downriver to Fulta, where the rest of the Calcutta merchants had taken shelter.

In 1756, the British East India Company became involved in a dispute with the new Nawab of Bengal, twenty-six-year-old Siraj-ud-duala. The young Nawab looked on the growth of the British settlement at Calcutta with both greed and suspicion. When he learned that the British merchants, in anticipation of war with France, had begun to expand their fortifications without his permission, he marched on Calcutta with 30,000 foot, 20,000 horse, 400 trained elephants and 80 cannon. The city was defended by a small, badly trained, force of soldiers and militia. Siraj-ud-daula attacked early on June 20.Anyone who could escaped down river by boat in a disorganized retreat. Those who had been unable to escape surrendered by mid-day and spent the night in the the Black Hole, a cell in which the British locked up drunken soldiers. The next day, the survivors were forced to leave Calcutta and made their way downriver to Fulta, where the rest of the Calcutta merchants had taken shelter.

The incident was made infamous by the account of one of the survivors, John Zephaniah Holwell. Published in 1758, Howell’s pamphlet, titled A Genuine Narration of the Deplorable Deaths of the English Gentlemen and others who were suffocated in the Black Hole, was popular reading in the eighteenth century and frequently reprinted. Holwell reported that 146 English, including one woman, were held in an 18 square foot cell with one small barred window; only 21 survived the night. Referring to his experience as “a night of horrors I will not attempt to describe, as they bar all description,” he went on to describe the event in horrific detail. The story became part of the mythology of empire when Thomas Babington Macaulay borrowed heavily from Holwell for his own lurid account of the incident in his 1840 essay on Lord Clive.

The incident was made infamous by the account of one of the survivors, John Zephaniah Holwell. Published in 1758, Howell’s pamphlet, titled A Genuine Narration of the Deplorable Deaths of the English Gentlemen and others who were suffocated in the Black Hole, was popular reading in the eighteenth century and frequently reprinted. Holwell reported that 146 English, including one woman, were held in an 18 square foot cell with one small barred window; only 21 survived the night. Referring to his experience as “a night of horrors I will not attempt to describe, as they bar all description,” he went on to describe the event in horrific detail. The story became part of the mythology of empire when Thomas Babington Macaulay borrowed heavily from Holwell for his own lurid account of the incident in his 1840 essay on Lord Clive.

There is no doubt that the men who attempted to defend Calcutta against Siraj-ud-daula, led by Howell himself, were incarcerated in the fort’s punishment cell, which was called the Black Hole by British soldiers. (The name continued to be used in army garrisons as late as 1863). Details of the story have since been disputed. Holwell’s numbers appear to have been exaggerated. More importantly, his claims of malice on the part of Siraj ud duala have been rejected. While it is clear is that the British prisoners were held overnight in a small, badly ventilated cell on the longest day of the year and that a substantial proportion of them did not survive, there is no evidence that the Nawab ordered the imprisonment or was even aware of it. British atrocities against Indian residents of Calcutta in the days before Siraj-ud-daula’s attack add balance to the story.

From the British point of view, retribution was rapid and thorough. Siraj ud duala’s attack on Calcutta was the first step in the events that would lead to the Battle of Plassey and the rise of the British Raj.

March 15, 2014

Blood Royal: A Medieval CSI Team In Action

In Blood Royal: A True Tale of Crime and Detection in Medieval Paris, medievalist Eric Jager returns to the world of medieval true crime stories that he popularized in The Last Duel.

In Blood Royal: A True Tale of Crime and Detection in Medieval Paris, medievalist Eric Jager returns to the world of medieval true crime stories that he popularized in The Last Duel.

On a cold night in November, 1407, a band of masked men assassinated Louis of Orleans, the powerful and unpopular brother of the intermittently insane King Charles, on a dark street in Paris. Blood Royal tells the stories of both the criminal investigation that followed and the subsequent impact of the assassination on French politics.

The first half of the book is told as a medieval murder mystery, based on working notes of the investigation written by Guillaume de Tignonville, provost of Paris and the law-enforcement officer responsible for finding who killed the royal duke. Except for the absence of modern forensic science, Tigonville’s investigation techniques will be familiar to any fan of police procedurals: from interviewing witnesses to tracing physical clues. Jager maintains a high level of suspense throughout the enquiry as Tigonville and his men eliminate suspect after suspect until they uncover the shocking solution.

The second half of Blood Royal, while equally interesting, is more traditional history. Jager examines the power vacuum in the royal family left by Orleans’ death, the civil war that followed, and Henry V’s opportunistic invasion of France. He ends with the rise of Joan of Arc on the horizon.

Blood Royal will appeal to history buffs,* true crime fans, and anyone who loves historical mysteries or police procedurals.

A Lagniappe**

If historical true crime calls your name, I’d like to call your attention to two more excellent books. I enjoyed them both, but some how never got around to mentioning them on the blog.***

Holly Tucker’s Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution is smart, riveting and occasionally gruesome. (There were passages that I would have read with my eyes closed if such a thing were possible.) Set in seventeenth century Paris, Blood Work tells the story of Jean-Baptiste Denis, a doctor who transfused calf’s blood into a well-known Parisian madman in his search for medical answers. Several days later, the madman died and Denis was charged with murder. If you like your mystery and history tied up with big questions about the point where morality and science meet, this one’s for you.

Holly Tucker’s Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution is smart, riveting and occasionally gruesome. (There were passages that I would have read with my eyes closed if such a thing were possible.) Set in seventeenth century Paris, Blood Work tells the story of Jean-Baptiste Denis, a doctor who transfused calf’s blood into a well-known Parisian madman in his search for medical answers. Several days later, the madman died and Denis was charged with murder. If you like your mystery and history tied up with big questions about the point where morality and science meet, this one’s for you.

For those of you who prefer your historical crime with a little less gore, I highly recommend The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han Van Meergeren by Jonathan Lopez. Smart, riveting and not at all gruesome, The Man Who Made Vermeers is a tale of forgers, Nazis and the glittering art world of the 1920s and 1930s. It’s probably the only book ever nominated for both a national Award for Arts Writing and an Edgar for best non-fiction crime book.

For those of you who prefer your historical crime with a little less gore, I highly recommend The Man Who Made Vermeers: Unvarnishing the Legend of Master Forger Han Van Meergeren by Jonathan Lopez. Smart, riveting and not at all gruesome, The Man Who Made Vermeers is a tale of forgers, Nazis and the glittering art world of the 1920s and 1930s. It’s probably the only book ever nominated for both a national Award for Arts Writing and an Edgar for best non-fiction crime book.

*That would be you, right?

** Or, if you prefer, “But wait! There’s more!”

***Sometimes it feels like blog post topics are like an impatient crowd. Most of them wait their turn, but one or two always elbow their way to the front.

Much of this review–minus the asides, the snarkiness, and the extras–previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

March 12, 2014

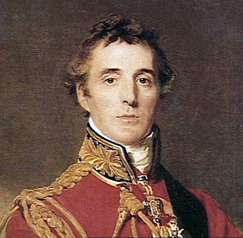

Introducing Flat Arthur, aka His Grace the Duke of Wellington

Several weeks ago, fellow Historical Novel Society member Cora Lee shared an idea that she’d been having fun with for a few months and asked if any of us would like to play along. She took the idea of “Flat Stanley” and gave it a historical twist, creating “Flat Arthur”– a two dimensional version of the multi-dimensional Arthur Wellesley, the first Duke of Wellington (1769-1842).*

Would I like to play along? Oh yeah! Over the next few months, Flat Arthur will travel with me hither and you. (Mostly to one library or another. Sorry, your Grace.) You can follow his travels and travails on my Tumblr site.

You doubtless know Wellesley as the general who defeated Napoleon at Waterloo, the feat for which he was created the 1st Duke of Wellington. Here are a few bits about Wellington that you may not know:

He gave his name to knee-high rubber boots.** He probably did not inspire Beef Wellington

He earned the nickname the “Iron Duke” during his first term as Prime Minister (1828-1830), thanks to his opposition to parliamentary reform. His position was so unpopular that he installed iron shutters on the windows of his home in London to keep angry crowds from smashing them.***

Wellesley enjoyed his first military successes in India through a combination of talent and nepotism. He fought at the Battle of Seringapatam against Tipu Sultan in the Fourth Mysore War. His older brother, Richard Wellesley, who was Governor-General of India, promoted him from colonel to major-general and named him Governor of Seringapatam and Mysore, honors that caused friction with senior officers who were by-passed in his favor. Major-General Wellesley retroactively earned his promotion with a stunning victory at Assaye in the Second Maratha War.

Stay tuned for more Wellington tidbits and Flat Arthur sightings.

* Here’s the blog post in which she introduced the idea for those of you who aren’t familiar with the original “Flat Stanley”.

**He could have given his name to something much less dignified than boots. The emperor Vespasian introduced public lavatories to Rome, where they are still known as vespasianos.

***The comparison with Margaret Thatcher, the Iron Lady, is irresistible. She embraced the nickname after it appeared in the headline of a piece in the Soviet newspaper Red Star, three years before she became Prime Minister. You can’t blame her: her previous political nickname was “Thatcher the Milk Snatcher,” earned when she cut free milk for schoolchildren from the budget during her tenure as Minister of Education. But I digress.

March 7, 2014

Dear Abigail

A million years ago, when I had first finished my doctoral dissertation and was tiptoeing toward writing about history for an non-academic audience, I headed off to a week-long writing class in Iowa. Along with the rest of my gear, I packed David McCullough’s then newly released John Adams, on the assumption that it would keep me interested during the down moments but wouldn’t distract me from the task at hand. Wrong. It kept me turning the pages like the most thrilling of thrillers.

Adams was fascinating, but the person who really caught my imagination was Abigail. I suspect I’m not the only one who felt that way. If you, too, are an Abigail fan, here’s your chance to learn more:

In Dear Abigail: The Intimate Lives and Revolutionary Ideas of Abigail Adams and Her Remarkable Sisters, Diane Jacobs returns to the topic of smart women in revolutionary times that she previously explored in her biography of Mary Wollstonecraft.

Readers are familiar with Abigail Adams thanks to her sharp-witted and loving correspondence with her husband. But John Adams wasn’t the only person who benefited from Abigail’s pen. In Dear Abigail, Jacobs uses the correspondence of Abigail and her sisters to build a picture of what it was like to watch the American Revolution from the sidelines.

Mary, Abigail, and Betsy Smith were the daughters of a wealthy and influential Massachusetts minister. They were highly educated, well read, and opinionated–and married men who valued those qualities. In their letters they complain about gender inequalities and household problems. They discuss the intellectual issues of the time from the theological questions of the Great Awakening to the philosophical underpinnings of revolution. They arrange to be inoculated for smallpox–a controversial issue at the time. They share news about the war. They worry about their parents, their husbands, and their children.

Much of the book deals with the day-to-day difficulties of the war. Of the three, Abigail suffered the most. (Some of the most poignant passages of the book show her struggling alone with a difficult pregnancy and ultimate stillbirth.) But all of them deal with shortages, lack of information, and fear.

Dear Abigail is the perfect pendant to McCullough’s John Adams: the American Revolution as seen through the eyes of three of its Founding Mothers.

Much of this review first appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

March 4, 2014

Re-Run: Cowboys and Indians, North African Style

Unlikely though it seems, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the French Foreign Legion over the last week.

I bet most of you have a few stock images of the Foreign Legion in your heads: men fleeing from their past into the desert and anonymity, absinthe, burning sands and blazing sun, those funny little billed caps with the flap down the back. (Extra points for anyone who knows what those caps are called.)

For most of us, those images come from trashy novels and B-movies that are kissing cousins to the American western at its least thoughtful. Both genres are heavy on the cavalry*, noble (or savage) armed horsemen as opponents, last chance saloons, and strong, silent heroes. Not to mention burning sands and blazing sun (see above).

And just like in the American western, the dangerous armed horseman on the ridge has his own version of the story.

Abd al-Qadir by Rudolf Ernst

Abd al-Qadir by Rudolf Ernst

If the French hadn’t invaded Algeria in 1830**, Algerian emir Abd al-Qadir would probably have been content to follow his grandfather and father as the spiritual leader of the Qadiriyah Sufi order. In the fall of 1832, when the French began to expand their control into the Algerian interior, the Arab tribes of Oran elected al-Qadir as both the head of the Qadiriyah order and as their military leader.

Al-Qadir led Arab resistance against French expansion in North Africa from 1832 to 1847. He was so successful that at one point two-thirds of Algeria recognized him as its ruler. The French signed treaties with al-Qadir and broke them. (Similarities to the American western, anyone?) After a crushing defeat in 1843, he was hunted across North Africa as an outlaw.

Abd al-Qadir surrendered at the end of 1847 and was imprisoned in France until 1853. Following his release, he settled in Damascus, where he entered the stage of world history one last time. In 1860, the Muslims of Damascus rose and began slaughtering the city’s Christians. When the Turkish authorities did nothing to stop the massacre, Abd al-Qadir and 300 followers rescued over 12,0000 Christians from the massacre. Once hunted by the French as a dangerous outlaw, Abd al-Qadir received the Legion of Honor from Napoleon III for his efforts.

Heroism is in the eye of the beholder.

*In fact, the Foreign Legion was an infantry unit. Just saying.

** Over what the French press called the Incident of the Flyswatter. I couldn’t make this stuff up.

February 27, 2014

Re-Run: Word With A Past–Maffick

The Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) started badly from the British point of view. British troops, supposedly the best trained and best equipped in the world, suffered a series of humiliating defeats at the hands of Boer farmers. (Anyone else hear echoes of another colonial war that pitted farmers against British regulars?)

The only bright spot in the morass of inefficiency and disaster was Colonel Robert Baden-Powell’s spirited–and well-publicized–defense of Mafeking, a small town on the border between British and Boer territory. (Yep. The guy who founded the Boy Scouts.)

The siege lasted for 219 days. Undermanned and inadequately armed, Baden-Powell improvised fake defenses, made grenades from tin cans, and organized polo matches and other entertainments to keep the garrison’s spirits high. The British public was able to follow “B-P’s” defense of Mafeking because the besieged town included journalists from four London papers, who paid African runners to carry their dispatches through the Boer lines.

When news of the garrison’s relief reached England, public celebrations were so exuberant that “maffick” became a (sadly underused) verb meaning to celebrate uproariously.

Maffick vt. To celebrate an event uproariously, as the relief of Mafeking was celebrated in London and other British cities.

Personally, I intend to maffick like mad when I turn this book proposal in.

February 25, 2014

Re-Run: If You Only Read One Book On Islamic History…

Last year I discovered the best general book on Islamic history I’ve ever read: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes by Tanim Ansary. I underlined as I read. I annotated. I put little Post-It tabs at critical points, the durable ones so I could go back to key arguments in the future. In short, I had a conversation with that book.

An Afghani-American who grew up in Afghanistan reading English-language history for fun, Ansary argues that Islamic history is not a sub-set of a shared world history but an alternate world history that runs parallel to world history as taught in the West. In Ansary’s account, the two visions of world history begin in the same place: the cradle of civilization nestled between the Tigris and the Euphrates. They end up at the same place: a world in which the West and the Islamic world are major and often opposing players. But the paths they take to the modern world, or more accurately the narratives that explain how “we” got to the modern world, are very different. Ansary’s book unfolds those two narratives side by side in clear, lively, and often amusing prose. I found his conclusions compelling.

If you’re only going to read one book on Islamic history, do yourself a favor: chose Destiny Disrupted. Then let me know what you think about it.