Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 116

September 5, 2014

In Which I Stop Reading And Start Writing

Yesterday I reached that undefinable moment in my current project when it is time to stop reading and start writing.

For smaller projects, the moment when I’m ready to make the leap is obvious. Sometimes I reach the point where I’m not learning anything new about my subject. Other times I reach the less satisfactory* point where I’ve read everything I can find to read and hope I can spackle over the holes in my knowledge as I go. Either way, it’s time to plunge in.

With larger projects, the line between research and writing is fuzzier. I’ve never found a way to measure “enough”. I certainly never reach the point where I’ve read everything there is to read. In fact, I regularly suffer from heart-pounding moments of panic when I realize that my source lists have spiraled out of control–again.**

And yet, that magic moment comes when I know it is time to make the leap. I can see the shape of the book. I’ve identified dramatic scenes or engaging details with which to catch a reader’s imagination. The pile of books as yet unread suddenly feels burdensome rather than exciting. I am restless, fidgety, eager to start. ***

I definitely don’t know enough yet to write the book. I probably don’t know everything I need to write the book proposal. I don’t even know what I don’t know. I will find holes, write past them until there is more hole than narrative, pause to search for answers, and write again.

Today I start.

When do you know it’s time to put down the book and pick up the pen start typing?

*i.e, absolutely terrifying.

**The seductive voice of the research demon can a terrible thing. I once identified 24 academic books as sources for a 250 word article before I caught myself.

***Okay, I’ll admit it. I’m always fidgety.

Image courtesy of The Wellcome Library

September 2, 2014

Jezebel or Joan of Arc?

In June, 1857, Lakshmi Bai, the Rani of Jhansi, belatedly committed herself and her kingdom to the revolt variously known as the Indian Mutiny, the Sepoy Rebellion, or the First Indian War of Independence.

In June, 1857, Lakshmi Bai, the Rani of Jhansi, belatedly committed herself and her kingdom to the revolt variously known as the Indian Mutiny, the Sepoy Rebellion, or the First Indian War of Independence.

A Break in Tradition

The rani had long-standing grievances against the British. She was the widow of Gangadhar Rao Niwalkar, ruler of the kingdom of Jhansi. Several months before his death, the childless raja adopted a distant cousin named Damodar Rao as his son and made a will naming the five year old boy as his heir.

Adopted heirs were an accepted practice in Indian kingdoms–both Gangadhar Rao and his predecessor were adopted heirs. Unfortunately for Lakshmi Bai and her son, under the rule of Lord Dalhousie the British began an aggressive policy of annexing Indian states on what now seem flimsy excuses, most notably the Doctrine of Lapse. The British already exercised the right to recognize the succession in Indian states with which they had client relationships. Dalhousie now claimed that if the adoption of an heir to the throne was not ratified by the government, the state would pass “by lapse” to the British. Not surprisingly, few adopted heirs were so ratified.

When Gangadhar Rao died in 1853, Dalhousie refused to acknowledge Damodar Rao as the raja’s legal heir to the throne and seized control of Jhansi. Laksmi Bai, with the support of the British political agent at Jhansi and the advice of British counsel, immediately contested the decision. She continued to submit petitions arguing her case until early 1856. All her appeals were rejected.

Growing Discontent

Meanwhile, discontent had been building among the sepoys in the British East India Company’s army, thanks to a number of British decisions that appeared to be designed to undermine the faith of both Muslim and Hindu sepoys and make it easier to convert them to Christianity. The final straw was the rumor that cartridges for newly issued Enfield rifles were greased with a combination of beef and pork fat. Since the cartridges had to be bitten open, such grease would make them an abomination for both Hindu and Muslim sepoys. British officers were slow to respond to the rumors. By the time they assured their men that the cartridges were greased with beeswax and vegetable oils, the damage was done. On May 8, 1857, discontent turned to rebellion at the army garrison of Meerut. Eighty-five sepoys who refused to use the Enfield rifle were tried and put in irons. The next day, three regiments stationed at Meerut stormed the jail, killed the British officers and their families, and marched toward Delhi, where the last Mogul emperor ruled in name only.

Thousands of Indians outside the army had grievances of their own against the British. Soon Indian leaders whose power had been threatened by British reforms rose up, transforming what had begun as a mutiny into an organized resistance movement across northern India.

On June 6, troops in the East India Company army in Jhansi mutinied. Two days later, they massacred the British population and soon left for Delhi. Given Lakshmi Bai’s long-standing grievances against their government, the British were quick to blame her for the rising in Jhansi, though evidence for her initial involvement is thin. In fact, she wrote to the nearest British authority, Major Walter Erskine, on June 12 giving her account of the mutiny and asking for instructions. Erskine authorized the rani to manage the district until he could send soldiers to restore order.

With the region in chaos, Lakshmi Bai soon found herself under attack by two neighboring principalities and a distant claimant to the throne of Jhansi. Finding it necessary to defend her kingdom, she recruited an army, strengthened the city’s defenses and formed and alliance with the rebel rajas of Banpu and Shargarh. As late as February she told her advisors she would return the district to the British when they arrived.

On March 25, Major General Sir Hugh Rose and his forces arrived at Jhansi and besieged the city. Threatened with execution if captured, Lakshmi Bai resisted. In spite of a vigorous defense, on April 3, the British broke into the city, took the palace and stormed the fort.

“The Bravest and Best”

The night before the final assault, Lakshmi Bai lashed her ten-year-old adopted son to her back and escaped from the fortress, accompanied by four companions. After riding 90 some miles in 24 hours, the rani and her small retinue reached the fortress of Kalpi, where she joined three Indian leaders who had become infamous in British eyes: Nana Sahib, Rao Sahib and Tatia Tope. Defeated again and again through May and into early June, the rebel forces retreated before the British toward Gwalior.

On June 16, Rose’s forces closed in on the rebels. At the request of the other leaders, the rani led what remained of her Jhansi contingent into battle against the British. On the second day of fighting she was shot from her horse and killed. Gwalior fell soon after and organized resistance collapsed.

British newspapers named Lakshmi Bai the “Jezebel of India”, but Rose compared his fallen adversary to Joan of Arc. Reporting her death to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, he said: “Although she was a lady, she was the bravest and best military leader of the rebels. A man among the mutineers.”

In modern India, Lakshmi Bai is a national heroine. Her story has been told in ballads, novels, movies and comic books. Rose’s praise is echoed in the most popular of the folk songs about her: “How well like a man fought the Rani of Jhansi! How valiantly and well!”

August 29, 2014

And speaking of road trips on the grand scale…

In Round About the Earth: Circumnavigation from Magellan to Orbit, historian Joyce E. Chaplin describes around-the-world voyages as geodramas in which travelers present themselves as actors on a global stage–a metaphor that she extends by dividing her history of circumnavigation into three “acts”.

Chaplin begins with the fearful sea voyages of early modern man, when mariners who attempted to sail around the world were as likely to die as not. She moves on to the confident years of the imperial age, when circumnavigation became both a tool and a beneficiary of Western domination. She ends with the renewed fears and challenges of circling the globe that arose first with aviation and then with space travel. The dangers of orbiting the earth in a space ship are surprisingly similar to those of circumnavigating the globe in a fifteenth century caravel.

Round About the Earth is more than a series of adventures, though Chaplin tells plenty of stories about both major and minor figures in a lively and engaging voice. (Magellan, who didn’t actually make it around the globe. Darwin, who never conquered seasickness. Laika, the first animal in space, whose terror, pain and death were broadcast via radio and television signals.) Chaplin intertwines her travelers’ accounts with discussions of the political contexts that defined them, the technological innovations that made them easier, and, perhaps most interesting of all, the way they were reported. From bestselling fifteenth century travelers accounts to NASA’s television broadcasts, circumnavigation has been about the story as much as about the adventure.

This review previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers

August 26, 2014

In which I set down my road map and consider the globe

My Own True Love and I recently decided to cancel our Great River Road Trip. It was a good decision; our old cat and our old house both require our attention and the Mississippi will still be there come spring.

Under the circumstances, it seems appropriate to consider a bigger picture than road signs, road maps and our GPS. In short, globes.

Globes: 400 Years of Exploration, Navigation and Power, by professional globe-restorer Sylvia Sumira, is a history of globemaking from the late 15th through the late 19th centuries, when globes were used as educational tools, scientific instruments, and status symbols. It is also breathtakingly beautiful.

The first two sections of the book are scholarly articles in which Sumira considers not only who made globes, but why and how. The first of these, “A Brief History of Globes”, is clearly for specialists. The second will fascinate anyone who has wondered how globe makers wrap a flat map around a ball–a step-by-step description of the construction of printed globes from the process of forming a papier-mâché sphere around a mold to the challenges of fitting 2-D printed sections (triangular pieces called gores) around a 3-D object.

The text is almost irrelevant next to the photographs of sixty historic globes, most of them from the collection of the British Library. They range in rarity from an unusual hand-painted globe made in 17th century China to mass-produced globes from the end of the 19th century. Sumira includes printed gores drawn by master cartographers, self-assembly paper globes made as inexpensive educational aids for children, tiny pocket globes, elaborate clockwork globes, celestial globes that map the heavens and an oddly modern 19th century teaching globe that folds up like an umbrella. The brief essays that accompany the photographs consider each object both in terms of its provenance and historical context and also as a work of art.

Certainly worth a spin, Globes will grab the imagination of anyone fascinated by maps.

This review (or at least most of it) previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

August 22, 2014

Salt

Anyone who sat through a third grade social studies lesson learned that Europe’s search for pepper changed the world. Prince Henry the Navigator, Columbus, and all that. But did you know that salt played an even bigger role in world history?

Unlike pepper, we can’t live without salt. It is as essential to life as water. Our bodies need it to digest food, transmit nerve impulses, and move muscles, including the heart.

When we were hunter-gatherers, the salt we needed came from wild game. (Sometimes wild game got the salt it needed by licking the places where we urinated. The circle of life can be weird.) As mankind settled and our diet changed, we had to find salt from other sources, not only for ourselves, but for the animals we domesticated.

In theory, salt can be found almost everywhere on earth. It fills the oceans, lies in rich veins in rock near the earth’s surface, and crusts the desert beds of long vanished seas. But until the Industrial Revolution, it was often difficult to obtain.*

The law of supply and demand is almost as dependable as the law of gravity. Because salt was hard to come by, it was valuable. It was one of the first international commodities and the first government monopoly.** Merchant caravans carried it across the most inhospitable places of the earth. Governments taxed it. Roman soldiers were paid in it.*** Mohandas Gandhi staged a protest around it.

The next time you pick up the salt shaker, show a little respect.

* The phrase “back to the salt mines” is rooted in that fact that mining salt was dangerous work, historically done by slaves or prisoners. As late as the mid- 20th century, both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany used labor in the slave mines as punishment.

** China, ca 221 BCE.

***Hence the phrase “worth your salt”. Not to mention the word “salary”, which comes from the Latin word for salt.

Image courtesy of Carlos Porto at FreeDigitalPhotos.net

August 19, 2014

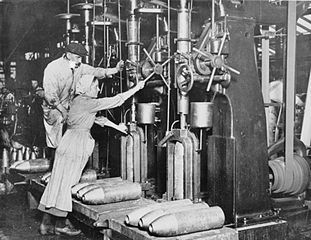

Before Rosie the Riveter…

A generation before Rosie the Riveter, munitionettes “manned”* Britain’s factories and mines, replacing the men who volunteered for General Kitchener’s New Army in 1914 and 1915.

Women were initially greeted in the work force with hostility. Male trade unionists argued that the employment of women, who earned roughly half the salary of the men they replaced, would force down men’s wages.** Some argued that women did not have the strength or the technical skills to do the work.

When universal male conscription was passed in 1916, need out-weighed social resistance. By the 1918, 950,00 women worked in Britain’s munitions industry, outnumbering men by as much as three to one in some factories.

The hours were long and the work was dangerous. Munitionettes were popularly known as “canary girls” because prolonged exposure to toxic sulphuric acid tinged their skin yellow. Deadly explosions were common.

Munitionettes were not the only women to enter Britain’s work force in World War I. Another 250,000 joined the work force in jobs that ranged from dockworkers and firefighters*** to government clerks, nurses, and ambulance drivers. The number of women in the transport industry alone increased 555% during the war.

At the end of the war, most of the munitionettes and their fellow war workers were replaced by returning soldiers. Many of them were probably glad to go. But the definition of “women’s work” had been permanently changed. The thin edge of the wedge had been inserted.

* So to speak.

** Evidently the simple solution of negotiated for women to be paid an equal wage for equal work did not occur to male dominated unions. As a consequence, women’s trade unions saw an enormous increase in membership during the war.

*** Imagine fighting a fire in a long skirt and petticoats.

August 16, 2014

Whose Remembrance?

2nd Rajput Light Infantry in action in Flanders, during the winter of 1914–15

A few statistics from the Imperial War Museum in London make it clear that the First World War was a global war in more than one sense:

Roughly 1.5 million soldiers from British India served in the war; 80,000 lost their lives. Many of them fought in the trenches on the Western Front–if you don’t believe me, check out the names of fallen Sikh, Muslim and Hindu soldiers on the Menin Gate in Ypres.

More than 15,000 soldiers from the Caribbean fought with the allied forces.

Tens of thousands of East Africans were drafted into a non-combatant Carrier Corps to support* British troops in Africa.

Chinese and Egyptian Labour Corps, with roughly 100,000 and 55,000 men, supported British troops in France and the Middle East

Taken together, those numbers change the face of World War I. And that’s not even counting participants from French colonies and “areas of influence”. Not to mention the segregated African American units who fought in France.

The Imperial War Museum is commemorating the WWI centennial with a wide ranging research project titled Whose Remembrance? focusing on the experience of the peoples of Britain’s former empire in the wars. The researchers seem to be asking questions not only about the topic itself but what it tells us about how history is constructed. This is worth watching.

*That word, supported, deserves some attention.

August 12, 2014

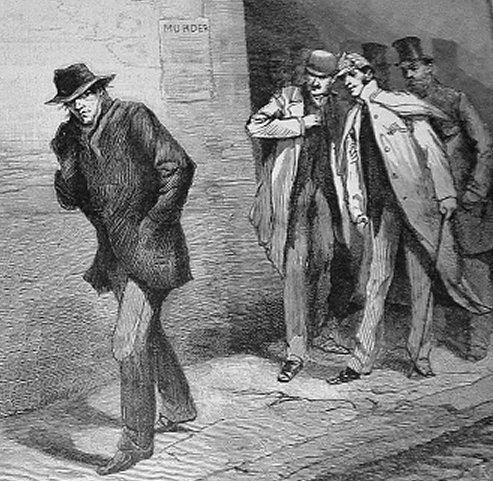

First Known Serial Killer Terrorizes The Slums of London

“A Suspicious Character” –one of a series of images from the Illustrated London News for October 13, 1888 carrying the overall caption, “With the Vigilance Committee in the East End”. (Notice the figure in the deer stalker cap–Sherlock Holmes in pursuit of Jack the Ripper?)

On August 6, 1888, Martha Tabram was stabbed to death in the Whitechapel neighborhood of London–many believe she was the first victim of the serial killer known as Jack the Ripper.*

Between August and November, five more women were murdered within a one-mile radius in London’s East End. All were prostitutes and all but one were horribly mutilated by their killer.

The East End was a notorious slum. Violence against prostitutes was not unusual. Tabram’s death received only a passing mention in the papers, described by The Daily News as a “supposed murder” even though she had been stabbed nearly forty times.* With the discovery of the second murder on August 31, the story became front-page news. The murders caught the public attention not only because of their brutality, but because of gloating letters sent to both Scotland Yard and the Central News Agency by a man calling himself Jack the Ripper. (Some or all of the letters may have been written by a journalist trying to heighten interest in the story.) Public opinion on the subject was so hot that both the Home Secretary and the London Police Commissioner resigned as a result of the failure to make an arrest.

From a historical perspective, the case provides a great deal of information about police procedure and life in the slums in Victorian London. Newspapers reported on the inquests, the investigation, and the appalling conditions prevalent in the East End. Reporters interviewed slum residents and police officers alike trying to keep the story alive.

Jack the Ripper was never caught and the number of his victims remains uncertain. (The police files included a total of eleven women whose deaths shared some of the elements associated with Jack the Ripper.) The case was officially closed in 1892, but his murders continue to fascinate armchair detectives–so much so that entire websites are devoted to “ripperology.” In the 125 years since his killing spree ended, Ripper enthusiasts have offered more than 100 possible identities for the killer, ranging from a German sailor on shore leave to Queen Victoria’s grandson Albert Victor, the Duke of Clarence.

* AKA The Whitechapel Murderer and Leather Apron. Whitechapel Murderer I get, but Leather Apron???

**Bad copy-editing? An odd variation on describing someone as a “suspected” or “accused” murderer prior to conviction? Because the fact that someone was stabbed 40 times does not necessarily mean she was murdered?

August 7, 2014

A Few WWI Books From the History in the Margins Archives

Just in case you missed them the first time around:

In The Lost History of 1914, NPR’s Jack Beatty takes on what he describes as the “cult of inevitability” surrounding the beginning of the war.

NPR’s Jack Beatty takes on what he describes as the “cult of inevitability” that surrounds historical accounts of the First World War. – See more at: http://www.historyinthemargins.com/20...

NPR’s Jack Beatty takes on what he describes as the “cult of inevitability” that surrounds historical accounts of the First World War. – See more at: http://www.historyinthemargins.com/20...

NPR’s Jack Beatty takes on what he describes as the “cult of inevitability” that surrounds historical accounts of the First World War. – See more at: http://www.historyinthemargins.com/20...

NPR’s Jack Beatty takes on what he describes as the “cult of inevitability” that surrounds historical accounts of the First World War. – See more at: http://www.historyinthemargins.com/20...

Who Made The Map Of The Modern Middle East? tells the story of how today’s Middle East was created from the remains of the Ottoman Empire during the peace negotiations are the end of the war.

Despite its title, The Making of the First World War: A Pivotal History by historian Ian F.W. Beckett is not another account of the events leading up to WWI. Instead Beckett is concerned with what he describes as “pivot points”: decisive moments that affected not only the course of the war but that of later history.

August 5, 2014

Shin-Kickers From History: William Wallace, aka Braveheart

Statue of Braveheart at Edinburgh Castle. (What? You were expecting Mel Gibson?)

In 1296, Edward I of England forced the Scottish king to abdicate and seized the throne of Scotland. Scottish unrest was immediate and widespread. It flared into full-scale rebellion in May 1297 when William Wallace led a raid against the town of Lanark, killing the English sheriff.* Under Wallace’s leadership, the Scots weakened the English hold on Scotland and raided across the border into England.** In late 1297, Wallace and his forces defeated a much larger English force at the Battle of Stirling. Wallace was subsequently knighted and made “guardian of the kingdom”, ruling Scotland in the name of its deposed king.

The victory at Stirling was a classic example of “win the battle, lose the war”. Edward marched north with his army to exact retribution. Wallace retreated deeper and deeper into Scotland. Edward followed. When the two armies met at Falkirk in July, 1298, the Scots were defeated and Wallace was forced to flee the battlefield.

Wallace resigned the title of guardian but did not give up his quest for independence. Turning to diplomacy, he sought support for the Scottish cause in France–the first step in what would be a centuries-long if occasionally shaky Franco-Scottish alliance against England.*** In his absence, Robert Bruce, Wallace’s successor as the guardian of the kingdom, negotiated a truce with Edward. Wallace refused to sign.

When Wallace returned to Scotland in 1303, Edward declared him an outlaw and offered a reward for his capture or death. For two years, Wallace continued to fight against English rule. He was captured near Glasgow on August 5, 1305–thanks to a tip from a fellow Scot–and taken to London where he was charged as an outlaw and a traitor. The result of his trial was a foregone conclusion. There was no jury and he was not allowed to speak in his own defense. Nonetheless, when accused of treason he denied the charge, saying he could not be a traitor because he had never sworn allegiance to the English king.

Wallace was drawn and quartered on August 23. His head was displayed on London Bridge. The quarters of his body were sent Newcastle, which he had savaged, and to Berwick, Stirling and Perth as a warning to would-be rebels.

Scotland regained its independence in 1328 with the Treaty of Edinburgh, only to lose it again with the Acts of Union in 1706-07. In the centuries after his death, William Wallace became an emblem of Scottish independence. (Contrary to popular belief, the winners don’t always write the history.)

Scottish independence is an issue once again, with a referendum scheduled for September 15. Polls suggest that a majority of Scots intend to vote yes for independence. Don’t touch that dial.

* The sheriff in medieval England was more than the local peace officer. As My Own True love puts it, he was a Big Wheel. The sheriff was the king’s officer at the level of the shire, responsible for collecting taxes, protecting the king’s hunting preserves, administering justice and, yes, keeping the peace.

**It’s only fair to point out that Wallace was a pretty brutal hero. He’s reported to have made a sword belt from the tanned skin of a fallen Englishman.

***Think Mary Queen of Scots. Think who supporter the Stuart pretenders.

Photograph by Kjetil Bjørnsrud. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons