Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 121

February 22, 2014

Re-Run: Road Trip Through History–The Utopian Communities of New Harmony

My Own True Love and I dearly love a road trip, especially if it includes a historical site or three, a quirky museum, a regional delicacy to try, walking paths, and plenty of roadside historical markers. (Anyone who thinks she might want to travel with us, be warned. We are the kind of people who turn off the road to find the historical marker rumored to be three miles to the west. )

Last weekend we packed cooler, notebook and walking shoes, said “hasta la bye-bye” to The Cat, and headed to southern Indiana.

New Harmony, Indiana, has been on our gotta-see list since last October, when I wrote about Robert Owen’s utopian community as part of a book on socialism. (Pausing for a blatant piece of self promotion. Close your eyes if it makes you queasy.)

New Harmony was home to two successive utopian communities.

The first was the Harmony Society, informally known as the Rappites: a German Pietist sect who split off from the Lutheran church at the end of the eighteenth century. They believed that the end of the world was near, but that didn’t stop them from hard work while they waited. Over the course of ten years, they successfully built a communal Christian republic in the Indiana wilderness.

In 1824, the Harmony Society sold their land and settlement to British reformer Robert Owen. Owen was a self-made factory owner with dreams of reforming society on communal lines. Self-sufficient Villages of Cooperation would replace private property. Owen’s New Harmony was less successful than that of the Harmony Society: too many artists and intellectuals and not enough farmer and tradesmen made self-sufficiency any more than a dream. In 1828, Owen sold the land to individuals at a loss.

Today the historic sites of New Harmony are well preserved and well presented, run by the University of Southern Indiana, the Indiana Historical Museums, and enthusiastic local volunteers.

We weren’t surprised that locals emphasize the achievements of the Harmony Society rather than Robert Owen’s failed experiment. We were surprised at their emphasis on weaving the past into the future. Museum architect Richard Meier, who later created the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, designed the visitor’s center, called the Atheneum in memory of Owen’s cultural experiment. Philip Johnson’s Roofless Church houses a statue by Jacques Lipschitz.

All told, we had a great visit: well designed historical exhibits, good food (eat at the Red Geranium if you go), a labyrinth to walk, old houses to look at, lots of historical markers along the way, and a few surprises. Just what a history road trip should be.

Everywhere you look, from the web site to the entrance of the Athenaeum, New Harmony asks its visitors, “What’s your vision of Utopia?” I don’t have an answer. What about you?

February 19, 2014

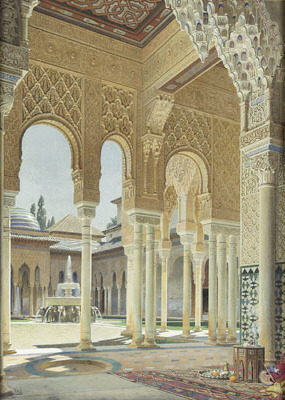

Re-Run: Muslim Spain–The Soundtrack

The perversity of the universe being what it is, the final stages of renovating our new-old house and finishing my book proposal have collided. Instead of driving myself mad trying to write blog posts or letting History in the Margins go blank for a few weeks, I decided to run some of my favorite posts from the days when only a handful of people read along. I hope to produce some new content along the way*, so re-runs will be clearly marked.

And now, without further ado, I bring you

Muslim Spain: the Soundtrack

These days, I’m spending a lot of time in Muslim Spain–a golden age of cross-cultural pollination by any standard. At a time when most of Europe was wallowing in the Dark Ages, Muslim Spain was a center of wealth, learning–and tolerance. If you wanted libraries, hot baths, or good health care, Spain was the place to be.

I recently discovered the perfect soundtrack for thinking about Muslim Spain: the ladino music of Yasmin Levy.

Ladino is the Sephardic equivalent of Yiddish. (Sephardic comes from the Hebrew word for Spain.) Spoken by the Jews of Muslim Spain, ladino began as a combination of Hebrew and Spanish. When their most Catholic majesties Isabella and Ferdinand expelled the Jews from Spain in 1492, most of them sought protection in the Muslim states of North Africa and the Ottoman Empire. Over time, their language took on elements of Arabic, Greek, Turkish, French, and the Slavic languages of the Balkans.

Ladino music, like the language itself, carries the history of the Sephardic community in its sound. It has elements in common with Portuguese fado, Spanish flamenco, Jewish klezmer music, and Turkish folk songs.

Today the ladino speaking community is small. Perhaps 20,000 speakers. Like other embattled language groups–the Gaelic speakers of Ireland, the French-speaking Cajuns of southwest Louisiana–Sephardic activists are working to keep their language alive.

Take a moment to check out this video of Jasmine Levy in performance:**

Remember. You heard it here first.

*I have some stories I’m dying to tell you. I want to tell you about Flat Arthur. I want to ponder the Roman Empire in the Middle East. I want to remember the Alamo. But first I need to get this dang proposal off to my agent and get a house finished.

**If you subscribe to History in the Margins by e-mail, you need to go to the website to see the video clip. Just click on the title.

February 14, 2014

An Extra Helping

I’ve recently started posting on Tumblr. Like History in the Margins, my Tumblr posts focus on history, writing, and writing about history, plus an occasional odd bit. Unlike my posts here, they are snapshots (sometimes literally) of what I’m working on, thinking about, and reading. I suppose you could describe them as Marginalia.

If you’d like a quick bite of history in between History in the Margin posts, drop on by: http://pdtoler.tumblr.com/.

February 11, 2014

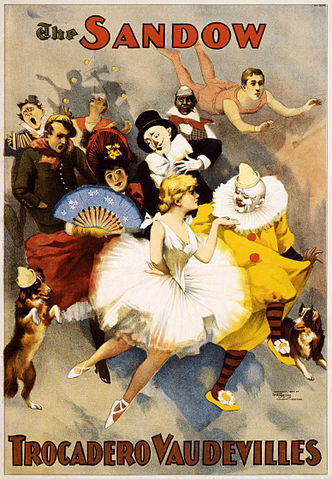

Word With A Past: Vaudeville

In 1648, revolution broke out in the streets of Paris. Known at the time as the Fronde ,* it was in many ways a rehearsal for the French Revolution(s) that would follow. Barricades went up in the streets. Aristocrats were pulled out of their carriages and shot at. Militias paraded in the public squares. There were threats of pulling down the Bastille.

In 1648, revolution broke out in the streets of Paris. Known at the time as the Fronde ,* it was in many ways a rehearsal for the French Revolution(s) that would follow. Barricades went up in the streets. Aristocrats were pulled out of their carriages and shot at. Militias paraded in the public squares. There were threats of pulling down the Bastille.

More important for the purposes of this blog post, the Fronde was fought in the media as well as in the streets. Printed placards were put up in public places and distributed door-to-door. Small notices, called billets (tickets), were strewn around the city streets. Peddlers sold political pamphlets on street corners like newspapers.** And satirical political songs, known as vaudevilles, became popular.

A contraction of the the phrase voix de ville (the voice of the town), vaudevilles were well named. Writers took popular tunes and wrote new lyrics to them about current events. Singers were paid to roam the streets and sing the latest tunes. Rich and poor alike would hum them as they went about their day. The songs became so popular that collections of greatest hits were compiled.

In eighteenth century France, vaudevilles became a way to get around restrictions on the theater. Theaters presented vaudevilles in conjunction with pantomime and comic sketches. Tap shoes optional.

* Slingshot, a name with a David and Goliath feel appropriate for a revolution that was, at base, about privilege.

** Almost a historical reference in its own right.

February 8, 2014

Déjà Vu All Over Again: Climate Change

Earlier this week I stood in a line that moved very slowly. As we waited, people began to tell weather stories–the natural consequence of five weeks of alternating snow and deep freeze. At first the stories focused on the efforts individuals had made to be in that line when the ticket office opened for a once a year event: digging out cars, walking through two feet of snow on un-shovelled sidewalks, etc. Then people moved on to tales of their experiences of the Big Chicago Snowstorm in 1967, or 1979, or 1999.

Just as I got to the head of the line, the snow began to fall again. A collective grumbling broke out. Then a voice from the back of the line said, “You know, winter used to always be like this.”

Whether that’s true depends on how you define “always”.

Over the life of our planet, glaciers have expanded and contracted more than twenty times at intervals of roughly a hundred thousand years, caused by tiny changes in the way the earth moves. “Brief” periods of interglacial warming* were followed by long periods of cold when ice covered the planet. Even those periods of warmth aren’t stable. In the most recent warm spell, following the Great Ice Age, we’ve experienced a number of dramatic climate changes, including:

The Medieval Warming Period

From roughly 800 to 1200 CE, Europeans enjoyed mild winters, long summers and good harvests. Warm centuries in Europe brought problems in other regions. Higher temperatures and changes in rainfall patterns created extended periods of drought in Central America, Central Asia, and South East Asia.

Cultural changes followed climate change. On the plus side: more stable food supplies help Europe take the first steps out of the “dark ages”,** favorable ice conditions allowed the Norse to travel pretty much everywhere, and reduced grazing land helped Genghis Khan to pull the Mongolian tribes together into an empire. On the down side: drought contributed to the end of the Chaco Canyon culture of modern New Mexico and Angkor Wat, favorable ice conditions allowed the Norse to travel pretty much everywhere, and reduced grazing land helped Genghis Khan to pull the Mongolian tribes together into an empire.***

Just to put things in context: the Medieval Warming Period was several degrees cooler than the recorded mean temperature since 1971.

The Little Ice Age

Between 1500 and 1850 CE (give or take 50 or 100 years) , things cooled off–at least in the Northern Hemisphere. Glaciers wiped out villages in the Alps. Rivers in Britain and the Netherlands froze deeply enough to support winter festivals. Even more amazing, in 1658, a Swedish army invaded Denmark by marching across the frozen Great Belt.

“Eighteen hundred and froze to death”

A violent volcano eruption in Indonesia on April 5, 1815, disrupted weather across the planet: more than twelve months of heavy rains in Europe, drought in North America and unseasonable cold everywhere.

I don’t know about you, but I suddenly feel a lot warmer.

* Brief in this case meaning 10,000 years or so.

**Short-hand for a more complicated discussion.

***Proving once again that plus or minus depends on where you stand.

Video of the Chicago Blizzard of 1967 courtesy of the Chicago Fire Department

February 5, 2014

Samurai: The Last Warrior

John Man combines travelogue, history and social commentary n Samurai: The Last Warrior, using the story of Saigo Takamori, popularly known as the “last samurai”, as his central focus.

John Man combines travelogue, history and social commentary n Samurai: The Last Warrior, using the story of Saigo Takamori, popularly known as the “last samurai”, as his central focus.

In 1877, Saigo led a hopeless rebellion against the Japanese government. Six hundred samurai armed with traditional sword and bow fought the government’s newly trained modern army in an effort to reverse the westernizing changes of the Meiji Restoration. When all was lost, Saigo committed ritual suicide; the institution of the samurai died with him. Three years after Saigo’s death, the government against which he rebelled erected a monument honoring him as a great patriot.

Man uses Saigo’s story as a lens through which to consider the history of the samurai, Japan’s rapid transformation from a feudal society to a modern one, and the ways in which samurai culture colors Japanese society today. He offers detailed explanations of both familiar elements of samurai culture, such as ritual suicide, and less familiar subjects, such as formalized sexual relationships between men. Man himself is never far from the page, whether comparing traditional samurai education with that of a British public schoolboy, visiting a class where a toned-down version of samurai-style sword fighting is taught, discussing the samurai in the context of other “honor cultures” (think street gangs), or explaining Darth Vader’s samurai roots.

Samurai is an engaging look at the final days of a military elite: a great choice if you’re interested in the the story of the last samurai (minus Tom Cruise) or the lasting influence of these warriors on Japanese culture.

A version of this review appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

February 2, 2014

Road Trip through History: The Colchagua Museum

We might not have gone to the Colchagua Museum in Santa Cruz, Chile, if one of our local hosts hadn’t recommended it so strongly. The guidebooks described it as a private collection that had been turned into a museum–something I always approach with the caution. Private collections fueled by a personal passion often create a museum that is not accessible to a viewer who does not share the passion. A wealthy collector is no guarantee that the collection will be coherent or interesting–though it will probably be well-displayed*

The Colchagua Museum focuses on Chilean history, from the prehistoric times to 2010. That’s a lot of ground for a moderately sized museum to cover. Not surprisingly, the museum is uneven in its presentation. But when it’s good–wow!

The rooms devoted to fossils, paleontology and pre-Columbian history are excellent. The artifacts displayed are some of the finest I’ve ever seen, interspersed with an occasional clearly identified reproduction needed to illustrate a specific point. The following points in particular grabbed my attention:

A very clear description of the appearance, division, convergence, and re-division of the continents over the millennia. I was aware of Pangaea, the super-continent that broke apart to form the continents as we know them. I wasn’t aware that Pangaea was probably preceded by at least one other supercontinent.

The megatherium was an actual prehistoric animal, not a detail made up by E. Nesbit in her wonderful children’s novel, Five Children and It. Some times the depths of my own ignorance amaze me.

One of the many failings of American history classes,** is that the only pre-columbian cultures we are taught about are the Aztecs, Mayans, and Incas.*** The Colchagua Museum outlines the range of Andean cultures that preceded the Incas in almost overwhelming detail.

The suggestion that the ancient Japanese may have reached South America, based on a perceived resemblance between artifacts of the Jōmon culture of Japan (10,000 BCE to 300 BCE) and the Valdivia culture of Ecuador (3500 BCE-1800 BCE). This strikes me as being roughly equivalent to thinking the ancient Egyptians settled Central America because the Central American cultures built pyramids. But I don’t really know enough about either culture to judge. I’m adding this to my Big List of Questions, but would be happy to hear from any of you who actually know something.

Once we moved past the Incas and into the rooms devoted to the period from the Spanish conquest through the nineteenth century, the exhibits felt more random. They seem to be based on the artifacts at hand rather than a clear sense of narrative.**** By the time we reached the extraordinarily handsome nineteenth century popcorn machine, we were ready to skip ahead to the exhibit that brought us to the museum.

The Great Rescue tells the story of the 33 Chilean miners who were trapped when the San José mine collapsed on August 5, 2010. For 69 days, the world watched as the Chilean government and an international team that included mining engineers, drilling experts and NASA worked to rescue the miners. It was a story that had everything: suspense, human interest, heroic engineering, and a happy ending.

The exhibit tells the story from many angles. The shanty town that grew around the mine entrance where family members waited to hear news. The history of the mine itself. How the miners survived before the rescue team made contact. The moment when a drill bit pulled up the first communication from the miners. The technical details of the rescue. The rescue itself. It ends with video footage of each miner being brought up and reunited with their families. My experience of the exhibit was both visceral and intellectual. I struggled with sympathetic claustrophobia, marveled over the technical brilliance of the solutions, and choked up more than once.

We had planned to go to the Darwin room after we finished the Great Rescue, but decided it would be an anticlimax.

* The Arthur Rubloff paperweight collection at the Art Institute of Chicago comes to mind. Pretty things, but do they really deserve their own gallery?

** By which I mean history taught in the United States, as opposed to classes about American history. Though now that I think about it, the failing is one of classes about American history taught in the United States.

***Indulge me in a small rant, will you? Obviously the only reason we are taught about these cultures is that they were standing on the shores when the Spanish invaded. (We tend to learn about the history of other countries only at the points where it intersects with our own interests.) Worse, from my perspective , our textbooks often describe these cultures as “ancient” even though they are clearly the contemporaries of the Europeans who invaded them. This is one side-step away from terming them “primitive”. Which they clearly were not.

****Though I was fascinated by a case that traced the history of printing in Latin America from pre-columbian seals to the nineteenth century printing press.

_____________________________________________________________________________

A few travel notes for anyone who finds themselves in central Chile

If you’re interested in eighteenth and nineteenth century history and have even a little Spanish, you’re better off going to the national historical museum in Santiago. The exhibits aren’t as flashy. They don’t have an audio tour (or English signs). But there is a clear narrative, not just one dang thing after another.

If you have several hours to spare, head down the road from Santa Cruz to the small town of Lola and visit the Chilean Craft Museum. Historical examples of traditional Chilean handicrafts shown in contrast with the work of modern artisans in those same crafts. Utterly fascinating, even without any Spanish.

Two words: wine tour. Trust me on this.

January 28, 2014

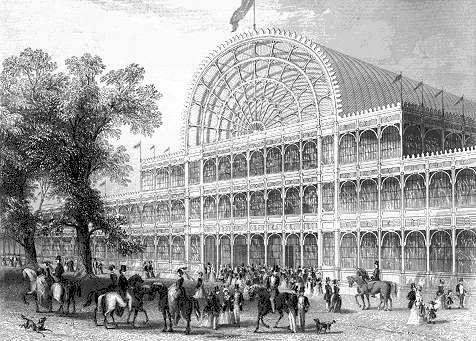

The Crystal Palace

Several weeks ago, My Own True Love and I ventured out into a frozen Chicago to attend an exhibition about the Columbian Exposition at the Field Museum. A meta-exhibit if there ever was one, Wonders of the 1893 World’s Fair deals with the changing nature of how we think about the world around us and the intellectual roots of many of today’s academic disciplines. It takes a quick glance at the colonial (and fundamentally racist) roots of anthropology, but it ignores the fact that the very idea of a World’s Fair was a by-product of British imperialism.

Which brings us to the exhibition popularly known as the Crystal Palace*: the first of the international exhibitions of industry and technology that came to be called World’s Fairs. Organized under the direction of Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, in 1851, the Crystal Palace made no attempt to hide the fact that it was an imperial exhibition. It was explicitly designed to be a celebration of Great Britain’s position as the “workshop of the world”.

Exhibits were requested from all over the world, but over half of the 14,000 exhibits represented Britain and its colonies. A 24-ton block of coal stood outside the entrance, an appropriate symbol of the industrial revolution that the exhibition celebrated. Exhibits included machinery, crafts, fine arts, and wonders such as the Koh-i-noor Diamond, on loan from Queen Victoria herself. The arched Centre Transept housed the world’s largest organ and was used as both circus tent and concert hall. The park surrounding the exhibition hall held copies of statues from around the world, a replica lead mine, and the first exhibition of life-size models of dinosaurs.

The name “Crystal Palace” was coined by the satirical magazine Punch as a commentary on the exhibition hall designed by Joseph Paxton, a gardener with a flair for building glass hot-houses. Built in less than nine months, the exhibition hall was itself a monument to British innovation and technology. Essentially a giant greenhouse, its framework of cast iron columns and girders was built with parts pre-fabricated in Birmingham. The nearly 300,000 panes of glass that made up its walls and roof were larger than anything constructed before.

The exhibition drew over six million visitors between May 1 and October 15. Prince Albert, like many later exhibition promoters who would imitate his event, emphasized its educational value. Most visitors agreed with Punch that the Exhibition was “Britannia’s great party”–and that a good time was had by all.

* It’s official name was the “Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry if All Nations”. Catchy, huh?

January 24, 2014

Flappers

The flapper of the 1920s took on a mythological character almost from the moment of her birth. With her short hair, short skirts and short attention span, she seemed like a new and unsettling breed of woman, one more aftermath of the First World War.

In Flappers: Six Women of a Dangerous Generation, Judith Mackrell explores the phenomenon through the lives of six prominent women who embodied “flapper-ness” for their contemporaries: African-American dancer Josephine Baker, actress Tallulah Bankhead, Lady Diana Cooper, steamship heiress Nancy Cunard, Polish-Russian artist Tamara de Lempicka and Zelda Fitzgerald. These women were not the flapper-next-door; thanks to both their talents and their excesses, they were tabloid fodder. They broke through the social barriers of gender, class, and, in Baker’s case, race–reinventing themselves in the process.

Part of the artistic and intellectual avant-garde, these six women experimented with new social mores and old vices. With no role models to follow, they grappled with the implications of their new independence, with often tragic results. Consequently, Flappers is not short on scandal, but it’s ultimately more than a titillating romp through the Jazz Age. Mackrell uses her larger-than-life subjects to illustrate the story of a generation in transition. She skillfully introduces social history on a personal and global scale, from dress reform and birth control to the demographic effects of the war, and ends with a thoughtful consideration of parallels with the youth culture of the 1960s. Sex, drugs, and red-hot jazz, anyone?

This review appeared previously in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

January 21, 2014

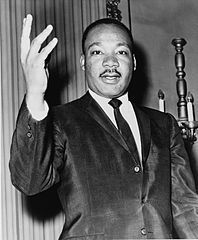

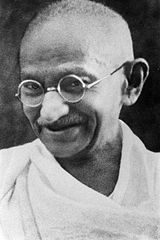

Shin-kickers From History: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Mohandas Gandhi

American civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. always claimed, “From my background I gained my regulating Christian ideals. From Gandhi, I learned my operational technique.”

The son and grandson of Baptist preachers in Atlanta, George, Martin Luther King went to Crozer Theological Seminary ready to fight for civil rights but full of doubts about the value of Christian love as a political strategy. He had adopted Reinhold Niebur’s philosophy that social evil was too intractable to be transformed by anything as simple as turning the other cheek.

A speech by Mordecai Johnson, then president of the largely Black Howard University, changed his mind. Johnson had just returned from India and had come back electrified by tales of Mahatma Gandhi’s successful struggle for Indian independence. Fascinated by Gandhi’s use of non-violent non-cooperation as a form of protest, the young theological student bought every book he could find on the Indian leader who had defeated the British empire with passive resistance and a spinning wheel. As he read, he became convinced that Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence was “the only logical approach to the solution of the race problem in the United States.”

King got his chance to apply Gandhi’s tactics for the first time in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955. On December 1st, at the end of a long work day as a seamstress in a local department store, Rosa Parks was tired and her feet hurt. She refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery city bus to a white man and was arrested. King, 27 years old and the new pastor of Dexter Street Baptist Church, was thrust into a leadership role in the protest against bus segregation that became known as the Montgomery bus boycott.

Under King’s leadership, the black protest remained orderly and peaceful. For thirteen months, the 17,000 Black residents of Montgomery refused to use the public bus system, even if it meant walking to and from work, adding hours to already long working days.

King and 90 others were arrested and indicted for illegally conspiring to obstruct the operation of a business. Unlike Gandhi and his followers, who accepted arrest as a natural consequence of civil disobedience, King appealed his conviction, thereby keeping his cause in the public eye and gaining a national reputation as a civil rights leader in the process.

In 1959, King made a pilgrimage to India as the honored guest of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who had been Gandhi’s right hand man during the battle for independence from Britain. He returned to the Unites States confirmed in his conversion to non-violence and inspired to follow the example of Gandhi’s satyagraha campaigns, particularly his march to the sea.

King’s approach to non-violent non-cooperation was not identical to Gandhi’s. The Hindu ascetic and the Baptist minister agreed that non-violence succeeds by transforming the relationship between oppressor and oppressed, allowing the powerless to seize power through self-sacrifice. But where Gandhi preached that the practice of satyagraha was rooted in patient opposition, King believed in actively confronting his antagonist.

On January 24, 1998, a statue of Gandhi was unveiled at the Martin Luther King Historical Site in Atlanta, commemorating the philosophical tie between the two men.