Pamela D. Toler's Blog, page 122

January 17, 2014

The Amritsar Massacre: Another Step Toward Indian Independence

Narrow entrance into Jallianwala Bagh

World War I brought India one step closer to demanding its independence from Great Britain.

Indian regiments sailed overseas and fought alongside their Canadian and Australian counterparts. (If you visit the memorial gateway at Ypres, you will see how many of them died in defense of the empire.) Indian nationalists loyally supported the British government during the war, fully expecting that British victory would end with Indian self rule on the dominion model.

Instead of self-rule, India got repressive legislation. The Rowlatt Acts, passed by India’s Imperial Legislative Council in March, 1919, continued the special wartime powers of the Defense of India Act. The new act took powers originally intended to protect India against wartime agitators, including the right to imprison those suspected of “revolutionary conspiracy” for up to two years without trial, and aimed them at the nationalist movement.

Indian members of the legislative council resigned their seats in protest. Mahatma Gandhi took the protest further, declaring a national day of work stoppage in the first week of April as the first step in a full-scale campaign of non-violent, non-cooperation against the so-called “Black Acts”.

The first implementation of the new laws occurred on April 10 in the Sikh city of Amritsar. The government of the Punjab arrested Indian leaders who had organized anti-Rowlatt meetings were arrested and deported without formal charges or trials. When their followers organized a protest march, troops fired on the marchers, causing a riot. Five Englishmen were killed and an Englishwoman was attacked. (She was rescued from the rioters by local Indians.)

Brigadier General Reginald Dyer was called into Amritsar to restore order. The situation called for diplomacy and good sense. Dyer used neither. On April 13, he announced a ban on public gatherings of any kind. That afternoon, 10,000 Indians assembled in an enclosed public park called Jallianwala Bagh to celebrate a Hindu religious festival. Dyer arrived with a troop of Gurkhas and ordered them to block the entrance to the park. Giving the celebrants little warning and no way to escape, he ordered the soldiers to fire on the unarmed crowd. They fired 1650 rounds in ten minutes, killing nearly 400 people and wounding over 1000.

In Britain, Dyer was widely acclaimed as “the man who saved India.” The House of Lords passed a movement approving his actions. The Morning Post collected £26,000 for his retirement and gave him a jeweled sword inscribed “Saviour of the Punjab.”

The government of India censured Dyer’s actions and forced him to resign his commission, but did nothing to stop local officials from continuing to inflame public opinion. In the Punjab, which remained under martial law for months following the Amritsar massacre, government officials acting “in defense of the realm” repeatedly humiliated and offended the people under their rule with actions such as making Indians crawl through Jallianwala Bagh.

Instead of “saving India”, Dyer accelerated Indian nationalist activity. Many Indians who had previously been loyal supporters of the Raj now joined the Indian National Congress, India’s largest nationalist organization. Bengal poet Rabindranath Tagore resigned the knighthood he had received after winning the 1913 Nobel prize for Literature. Motilal Nehru, president of the Congress and father of the first president of independent India, declared that “all talk of reform is a mockery”. Attempts to become equal partners within the Raj were almost over. Soon the push for independence would begin.

This post previously appeared in Wonders and Marvels.

January 14, 2014

History of the World in 12 Maps

This post is about a book, a book review, and the discussion that the review sparked.

As I’ve mentioned before, I review books for Shelf Awareness for Readers. Mostly history, a little reference–and the occasional cookbook because writer does not live by history alone. Some of the books I receive for review are on subjects I’d never think to read on my own.* Others scream my name immediately. Guess which category A History of the World in Twelve Maps fell into?

Here’s my review for Shelf Awareness:

Mapping is a basic instinct, argues Jerry Brotton: humans and animals alike use mapping procedures to locate themselves in space. Map-making, on the other hand– using graphic techniques to share spatial information-is an act of the human imagination. It is never objective; the map is not the territory. And maps of the world are more subjective than most, embodying the worldview of the culture that produced them. In A History of The World in Twelve Maps, Brotton, a British history professor, looks at twelve world maps, the people who created them, and what they tell us about the time and place in which they were made. In the process, he tells the reader a great deal about how we view the world today.

Beginning with Ptolemy’s Geography and ending with the virtual maps of Google Earth, Brotton considers maps and geographical theory from Islamic Sicily and fifteenth century China as well as the more familiar worlds of medieval England and Renaissance Europe. He looks at different approaches to shared questions: how a map is oriented (north is not the universal answer), what scale to use, where the viewer stands in relation to the map and how to project a round earth on a flat surface. Along the way, he considers politics, religion, cosmology, mathematics, imperialism, scientific knowledge, and artistic license. Each map is unique; all have features in common.

A History of the World in Twelve Maps is global history in the most literal sense: twelve variations on a universal theme.

Normally I would simply re-post the review here in the Margins, with proper attribution to Shelf Awareness, and hope that it directed a few more readers to an excellent book. However, this review prompted some interesting responses from readers that I would like to share.

Graham Thatcher wrote to me with an idea about maps and perception, which he has given me permission to share:

…while teaching a persuasion course, I took a National Geographic Mercator map of the world, blocked out the names of countries, and hung it upside down on the board. We had been investigating how our individual “world views” develop and when confronted with an antipodal projection, our literal world view was unrecognizable.

I think this is brilliant and intend to try it as soon as we move into the new house, where I’ll have a bigger office and a bit of wall space.

On a similar note, fellow historian, and long-time co-conspirator, Karin Wetmore sent me the following link to an interesting map/memory/perception project: http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/01/what-you-get-when-30-people-draw-a-world-map-from-memory/282901/

What ideas do you have about turning the world–or at least our map of it–upside down?

* Being knocked off my usual paths occasionally is one of the intangible benefits of reviewing.

January 10, 2014

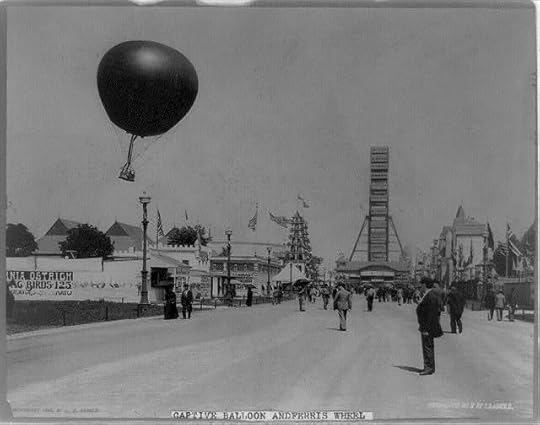

History on Display: Wonders of the 1893 World’s Fair

Last Sunday My Own True Love and I cocked a snook at cold and snow* and headed out to Chicago’s Field Museum to see what we thought was an exhibit on the 1893 World’s Fair, aka the Columbian Exposition. We had neglected to read the subtitle for the exhibit: “Opening the Vaults”. As is often our experience, what we got was much more interesting than what we expected. We thought we were going to an exhibit on the relatively familiar story of how the fair was developed: financial panic, Ferris Wheel, Little Egypt, and all.** Instead we were introduced to changing ideas about natural history and the story of how the Columbian Exposition led to the creation of what is now the Field Museum.

After a brief introduction to the fair itself,***the exhibit went on to consider four types of knowledge exhibited at the fair: animal, vegetable, mineral, and cultural. Using objects from the Field’s collections that have not been on display since 1893, the curators explained the cultural assumptions that shaped exhibits at the fair, how the exhibits developed into the Field’s collection, changes in the relevant academic disciplines in the intervening 120 years, and how modern scholars use specimens exhibited at the fair to answer new questions . If that sounds dry, it’s my fault. The exhibit itself is fascinating.

Here were some tidbits that had me reaching for my pen and notebook:

The Columbian Exposition, like the American space program, produced lots of unexpected spin-offs. For example, the company that insured the fair was worried about whether the unprecedented use of electric light bulbs was safe, so the fair’s organizers hired electrician William H Merrill to inspect the grounds. Building on his work on the fair, Merrill later founded Underwriters Laboratories (UL), a company that still tests and certifies the safety of electrical products.

Prizes were awarded to exhibitors for innovative product development. One of the first place winners still flaunts its success: Pabst Blue Ribbon Beer.

Two popular cereal products made their debut at the fair: Shredded Wheat and Cracker Jacks. Can you say “ends of the spectrum”?

The fair organizers were interested in “economic botany”. Many exhibits focused on plant products with economic potential, from raw indigo to cannabis seeds. Yes, you read that correctly. Cannabis seeds. As in pot.

I was stunned to learn that Elmer Riggs, the Field Museum’s first paleontologist, is credited with “removing ‘brontosaurus’ from the dinosaur vocabulary” ca 1903. Brontosaurus has certainly been part of my personal dinosaur vocabulary. (Thank you, Fred Flintstone.) A quick search revealed that the brontosaurus of popular culture was a mistake of the so-called Bone Wars in the early years of paleontology. Dang.

Labrador Inuits who had been hired to demonstrate their way of life in one of the “native villages” were so outraged by the conditions provided by the fair’s organizers that they sued the Fair, left the official village, and set up their own paid exhibit outside the Fair’s gates.

Wonders of the 1893 World’s Fair runs through September 7. It won’t be traveling to another museum. If you’re in the area, or if you’re obsessed with the Columbian Exposition and willing to travel, it’s well worth a visit.

*If you prefer your museum experience unhampered by other viewers, early Sunday morning is always a good choice. Early Sunday morning with blowing snow and falling temperatures is even better.

** Devil in the White City, anyone?

***Including the claim that the Columbian Exhibition is considered the greatest of the world’s fairs. Personally I think the grand-daddy of international exhibitions, the Crystal Palace exhibition of 1851, has a good claim to that title.

Photographs courtesy of the Library of Congress.

January 7, 2014

Road Trip Through History: Museum of Memory and Human Rights

The Bombing of La Moneda (the Chilean equivalent of the White House) on September 11, 1973, by the Junta’s Armed Forces.

My Own True Love and I went to Chile over the holidays for a family wedding and a spot of adventure. We set off knowing where we needed to be when and no idea about the details. We discovered strawberry juice, pisco sours, enormous holes in our knowledge of Chilean history, and the amazing kindness of strangers. We spent two nights in a cabin that looked like a hobbit hole, walked in the foothills of the Andes, and stayed up much later than we are used to.

Along the way we visited a truly powerful museum: the Museo de la Memoria et los Derechos Humanos (The Museum of Memory and Human Rights).

The museum documents the events of the military coup of September 11, 1973,* the subsequent abuses of the Pinochet years, the courage of those who stood against the regime, and the election in which Chile voted Pinochet out of power in 1988.** The exhibits are an assault on the senses, using contemporary film clips, music, photographs, and recordings. Photographs of the regime’s victims “float” against a glass wall that is two-stories high. Interviews with survivors of the coup were fascinating; interviews with survivors of the government’s human rights abuses were almost unbearable. A recording of President Allende’s final speech, broadcast under siege from the presidential palace shortly before his death, was awe-inspiring. In short, the museum shows humanity at its best and its worst.

In many ways, the Museo de la Memoria resembles Holocaust museums we’ve visited, not only in its insistence on memory and celebration of survival, but in its message of “never again”. A quotation from former Chilean president (and now president elect) Michelle Bachelet Jeria is engraved at the entrance that sums up the museum’s purpose: “We are not able to change our past. The only thing that remains to us to learn from the experience. It is our responsibility and our challenge.” Statements about and explanations of the universal declaration of human rights, passed by the United Nations in 1948, are interwoven throughout the historical exhibits.

I cannot say we had a fun morning. My Own True Love and I left the museum drained. We also were very pleased we made the effort. If you are lucky enough to have the chance to visit Chile, make the time to visit. If you don’t see Chile in your future but would like to know more about Chile under the Pinochet regime, these two books come highly recommended: Andy Beckett’s Pinochet in Piccadilly: Britain and Chile’s Hidden History and Hugh O’Shaughnessy’s Pinochet: The Politics of Torture. I haven’t read either of them yet, but I’m putting them on my need-to-read list.

*The United States is not the only country to remember 9/11 with sadness.

**I don’t know of any other instance in which a dictatorship allowed itself to be voted out of power. Do you?

Photograph courtesy of the Library of the Chilean National Congress

January 3, 2014

Boundaries

WARNING: THIS POST IS MORE ABOUT MY THOUGHT PROCESS THAN ABOUT HISTORY QUA HISTORY. FEEL FREE TO ABANDON SHIP IF THIS IS NOT YOUR THING.*

A couple of weeks ago, one of my favorite bloggers in the writing/publishing/creativity world, Dan Blank, wrote a post about choosing a single word to explore over the course of the year. I’ve read about this idea before–several times. I’ve always thought “interesting” and moved on without a pause. This time a word popped into my mind: boundaries.

It’s a word that has a lot of personal resonance for me, but that’s of no interest to you all, except to the extent that my success at defending my time to write, read, think and take road trips with My Own True Love keeps me primed to write blog posts. No mental fuel, no History in the Margins.

But the idea of boundaries is important to me in another way: it’s one of the concepts that holds my eclectic and hopefully electric vision together. I’m fascinated by the times and places where boundaries (literal and metaphorical) blur and the people who kick them down. I like to watch the way they move over time.** I’m interested in the expansion and dismantling of empires. I’m fascinated by frontiers and people who boldly go–where ever.

Over the course of 2014, I plan to think about boundaries: personal, historical, cultural, social. I suspect a lot of that thinking will show up here.

What about you?

◆ Is there a word that sums up (in part or in whole) your ideas about history?

◆ What are your thoughts about boundaries?

◆ Is there a word you plan to think about in 2014?

Onward!

* I hear the grumbles. First a holiday break, now a little musing. Don’t worry I’ve got some hard core history lined up for the next post.

** Have I mentioned how much I like maps?

December 24, 2013

Taking a Holiday

For the first time since I started History in the Margins, I’m going to take a planned break from blogging.* Unless I stumble across something that I feel I absolutely need to tell you RIGHT NOW, I’ll be back on January 3.

In the meantime, have a merry/jolly/happy/blessed time as you celebrate the victory of light over the darkness in the tradition of your choice.

*Which is not to say that there haven’t been some unplanned gaps.

December 20, 2013

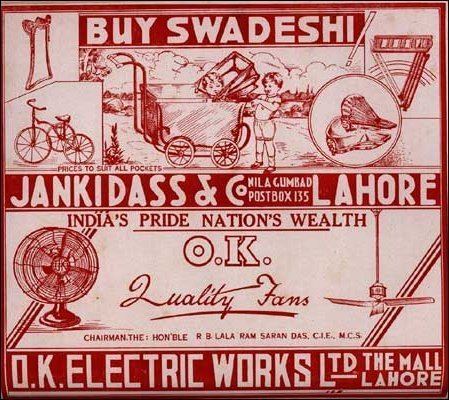

The Swadeshi Movement: The First Step Toward Indian Independence

Beginning in the 1830s, the British East India Company provided Western education to a small number of Indian elites: it was cheaper and more effective than recruiting the entire work force of the empire back home in Britain. In addition to training clerks of all kinds, the East Indian Company created as a by-product what Thomas Babington Macaulay described as “a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect”. A large proportion of this class came from Bengal province, home to Calcutta, then the capital of British India. Calcutta soon became the center of a thriving Indian intelligentsia.

Following the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857, expanded opportunities for Western education and Queen Victoria’s proclamation of equal opportunity for all races seemed to open the door for advancement. A generation of young Indians saw Western education as the path to jobs in law, journalism, education, and, most importantly, the Indian Civil Service. They soon discovered that the door was less open than it initially appeared. Thwarted in their desire to play a larger role in India’s government, the most politically conscious among them founded India’s first nationalist organizations. At first, their model was not the United States but Canada: not independence, but self-rule within the Commonwealth.

In 1905, the Indian government divided Bengal into two provinces, leaving its powerful western-educated elite a minority in its own homeland. The official explanation for the division was bureaucratic efficiency. The western-educated Bengali elite saw it as an attempt to undercut their power base.

Bengalis signed petitions against the partition and marched in protest through the streets of Calcutta. They also boycotted British imports, especially British cloth. Protestors burned British-made saris and other cloth to the cry of swa-deshi (of our own country). Wearing clothing made from swadeshi cloth became an emblem of nationalist beliefs. A few leaders called for Indians to boycott not only British goods, but British institutions, knowing that the law courts and government services could not function without the support of Indian employees. The movement soon spilled over into other regions of India.

As swadeshi sales grew and India’s industrial base boomed, the Indian government cracked down. The movement’s leaders were arrested. Politically active students found their financial air threatened. The police attacked protest marchers with long, metal-tipped poles called lathis.

After several years of increasingly violent protests, the Indian government annulled the partition of Bengal and instituted a series of reforms designed to give Indians a voice in local government. At the time, nationalist leaders were hopeful that they had taken the first step toward self-rule. In fact, the partition of Bengal proved to be the first in a series of decisions made over the next thirty years that would drive Indians to demand their independence.

December 17, 2013

Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas

It will come as no surprise to regular readers of History in the Margins–or anyone who browses my office bookshelves–that I am fascinated by maps. As I’ve mentioned before, history happens in both time and space. How can you understand an event/culture/war/empire if you don’t have a feel for its geography?

As someone interested in the times and places where cultures meet, draws lines in the sand, and change each other, I am also fascinated by New Orleans*–a city formed by the meeting and melding of cultures.

You can imagine my delight when Shelf Awareness sent me a copy of Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas to review.

Unfathomable City is no standard atlas. Essayist Rebecca Solnit and film-maker Rebecca Snedeker bring together writers, artists and cartographers to consider New Orleans, a city in which the lines between races, cultures, and even water and land blur and shift. Environmentalists, geographers, scholars, local experts and newcomers to the city explore New Orleans through the lenses of their respective concerns, their findings presented in 22 full-color, two-page maps and related essays.

The initial map and essay illustrate “How New Orleans Happened”, mapping three centuries of expansion and its causes. With the basic history and geography of the city established, the book goes on to explore both the things “everyone knows” about New Orleans and unexpected aspects of an eternally surprising city. Maps on cemeteries, the petroleum and natural gas industries and carnival parade routes are juxtaposed with maps on Arabs in New Orleans and the city’s role in the international banana trade Several maps join topics that at first seem unrelated– seafood and the sex trade, housing developments and the music industry–bringing new revelations in the process.

With beautiful maps and challenging essays, Unfathomable City presents New Orleans as infinitely complex and ultimately unknowable. The result is not a comprehensive guide to the city, but an invitation.

*But then, who isn’t fascinated by New Orleans?

A version of this review previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

December 14, 2013

Road Trip Through History: The Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum

More than a month ago I promised you a report on our visit to the LBJ Library. I fully expected to sit down and write it later that week. The fact that I wandered off into other historical by-ways is simply a reflection of how easily I’m distracted, not on the quality of the museum.

The Johnson Library was an eye-opener for me. Johnson was the president of my early childhood. My memories of him are limited to black and white photographs, set against a mental background of images from the Vietnam War. Laid over that was the image of Johnson as a major reform president, thwarted by the conflicting demands of the Great Society and the war*–the result of writing a book on the history of socialism.** I left the museum with a stronger sense of Johnson as man and as president–and a deep respect for his accomplishments. Historian Robert Dallek describes Johnson as “a tornado in pants”. That’s pretty dang accurate.

Here were some of the things that took me by surprise:

Johnson’s first job was teaching school in a rural district in Texas. His students were underprivileged Hispanics, who struggled against both poverty and discrimination. That experience shaped his political goals. If a president ever deserved to be known as the “education president” it was LBJ.

Pictures of the young LBJ with lots of hair.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, LBJ (then 33) was the first member of Congress to volunteer for active duty.

The sheer scope of reforms that his administration put in place, from civil rights bills to Head Start, the National Endowment for the Humanities, Medicare, the Clean Air Act. Johnson submitted eighty-seven bills to the first session of the eighty-ninth Congress. Eight-four of them passed.

I was particularly taken with a series of stations titled “Please hold for the president”. You pick up a telephone and hear actual phone calls made by President Johnson to members of his cabinet, members of Congress, and other political figures. It gave me chills to listen to him assure Martin Luther King, Jr. of his support for the civil rights movement. It amused me to hear Ladybird critique one of his speeches–she gave it a solid B. A tender conversation with Jacqueline Kennedy soon after her husband’s assassination brought tears to my eyes. And a call where the secure White House line got crossed with a long distance call between two ordinary American homes was laugh out loud funny.

If you’re in Austin, take the time to visit.***

*”Guns and butter” is a hard motto to live up to.

**Blatant self-promotion alert

**Heck, if you’re near any presidential library, take the time to visit. We’ve been blow away by both the Truman and Johnson libraries this year.

December 11, 2013

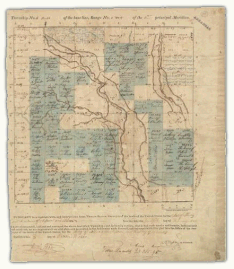

Word With a Past: Doing A Land Office Business

In 1785, the newly created United States, burdened by debts incurred in its war for independence, passed a Land Ordinance Act authorizing the Treasury Department to sell land in the public domain as a source of revenue.*

Acting on the principle of “survey before settlement”, tracts of land were surveyed into townships and plat parcels, then sold at auction to the highest bidder, or at least the minimum price set by Congress. Eager settlers poured across the Allegheny Mountains into first the Ohio lands and later the Indiana and Illinois territories. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 brought new opportunities for settlement in the “empty” territory west of the Mississippi.** Between 1800 and 1812, Congress created 19 land districts in the frontier territories and the Treasury Department sold more than 4 million acres of public land. In 1812, Congress created the General Land Office to manage the quickly growing sale of public lands.

Settlers were so eager to file land claims that district land offices were busy places. By 1832, so many claims for land had been filed that there was a backlog of some 10,500 land “patents” waiting for an official signature to make them final.*** “Land-office business” became a metaphor for a brisk business of any kind. It still is–even when the real estate market takes a turn for the worse and a two bedroom coop just won’t sell.

*If you’ve been hanging around History in the Margins for a while, this may sound familiar. America’s first interstate, the National Highway, was funded in large part by selling off bits of what became Ohio.

**Which were of course, not actually empty.

***At first all land patents were signed by the president of the United States. On March 2, 1833, Congress passed a law allowing a GLO clerk to sign on the president’s behalf.