Andrew Scott's Blog, page 40

October 2, 2012

For a Limited Time Only: Get 2 Books from Press 53 for $10!

That’s right, two books for ten dollars (plus three dollars shipping, making a grand total of thirteen dollars)! Press 53 is celebrating its 100th title by giving you access to this outrageous, limited time offer! To find out more and redeem your offer, click here!

September 20, 2012

"Then they all gathered around Sonny and Sonny played. Every now and again one of them seemed to say,..."

- James Baldwin, “Sonny’s Blues”

September 16, 2012

Literary Events in Central Indiana

September has been a great month for literary events in central Indiana. Antonya Nelson read at Purdue University on 9/6, while Dan Wakefield spoke at Indy Reads Books that night. Margaret Atwood visited Butler University last week. Jess Row will read at Purdue this week, while poet Eugene Gloria will read on the DePauw University campus. Next week, Antonya Nelson will give a craft talk at DePauw, where she holds the Mary Rogers Field Distinguished University Professorship for Creative Writing this semester. Later this semester, Robert Boswell will visit DePauw, while Yiyun Li and Robert Pinsky will come to Butler.

Here’s a video of Boswell reading from the title story of The Heyday of the Insensitive Bastards.

August 31, 2012

calvinandhobbesgifs:

calvinandhobbesgifs.tumblr.com

August 22, 2012

Writer-on-Writer Crimes: A Postscript

Why did I wade into this muck? I was thinking of how Alix Ohlin, or anyone in her position, might feel. Empathy should be an essential and required part of any fiction writer’s approach. I don’t really know her, though we are Facebook friends. My post wasn’t just about that review, which is only one element in a series of recent events—a few snarky pieces about writers masquerading as praise, ongoing commentary about reviews (positive and negative), and the “clubby” culture of writers interacting on Twitter/Facebook.

Because Ohlin’s books have been out for three months, some have suggested that the NYTBR may have shelved this review back in June, but brought it out after this “reviews are too nice/writers online are too nice” discussion emerged. We might never know the exact sequence, but I am curious. I would like to know if they assigned the review to Giraldi, and why, or if he pitched the review.

That said, I didn’t write “Writer-on-Writer Crimes” to defend Ohlin or any of the other writers mentioned. I’m still waiting to receive Ohlin’s books; I haven’t read them, as I made clear in the post.

Sometimes the responders I’ve interacted with seem stranded on the other side of a wide canyon we can never hope to cross, so different are our interpretations. A few disagree that Giraldi’s review is a takedown of realism, despite a line that’s against “earnest realism” in the review. I suppose one could say he’s only against realism when it’s earnest, but Ohlin seems interested in exploring many sides of realism, often moving toward the fabulist, as Giraldi notes. One commenter insists that Giraldi’s own fiction is realistic, and therefore he can’t be against realism, but when I pointed out that his novel is about a man “confronting creatures both mythic and real—Bigfoot on the Canadian border, space aliens in Seattle,” etc., I’m told that’s still realism. Maybe the book employs certain elements of realism. But space aliens equal realism?

Others were unwilling to even consider the possibility that Ohlin’s prose could be anything but bad, given the tiny samples quoted in Giraldi’s argument. I seemed unreasonable to some for suspending judgment about her prose; there are many ways a writer can use clichés, I said, and since I know Ohlin is sometimes quite funny, it’s not hard to imagine at least a few of those ways. I still contend that a review arguing against an author’s prose style should include a fuller, more representative sample. After I read Inside and Signs and Wonders, if I agree with Giraldi’s sentiments about Ohlin’s prose, I’ll say so. I’m not against honest criticism or negative reviews, only nasty ones—and my most sincere concern, reading the review, is that he did not honestly approach the books with the hope of liking them. He did not read Ohlin’s work on its own terms. He faults her for not doing what he would do, instead of faulting her for failing at what she set out to accomplish.

Still, I caught the most flak about linking to the piece about Cheryl Strayed. Some wrote to say I was being unfair, and that the jealous woman’s post was “500% positive,” as one friend said. So I read it again. There is no longer any mention of Strayed’s 10 extra pounds and shoddy clothes, and no mention of this seriously important edit. No wonder people thought I was being unfair. They didn’t read the same post I did. The piece is still link bait, regardless. Could she have included Strayed’s name a few more times? Even in the edited version, there’s still a mocking tone applied to the “sisterhood” and the rest. I get madder the more I think about this. You want to be Sugar? Maybe you should start by actually reading her columns. Take her advice. Don’t do something like this again.

In the end, some of my comments seem a little hypocritical. I said that extremely nasty reviews are often about the reviewer climbing ladders, staking out some kind of position, carving out an identity, and getting known. Even though a nasty review distances potential readers, there are still gains to be had, which is why everyone from Colson Whitehead (in his 2002 review of Richard Ford’s story collection[1]) to young writers without any publications will raise hackles and rile up “the writing world” (a phrase I’ve seen a hundred times in the last few days).

Some have said my own post is also self-promotion, but I wasn’t “reviewing the review,” as some have said, and I didn’t write about myself. It’s mostly commentary on the last few weeks, and a quick rhetorical analysis of Giraldi’s review. I didn’t write it to promote a tiny collection of stories that’s been out for 15 months. One man noted that my post was published on a website bearing my name, a clear indictment of my own wish to climb ladders and become known. When I pointed out that I published this post on the blog portion of my author website—you know, because it’s a blog post and I’m an author with a website—he never responded. I also didn’t call for Giraldi to be blacklisted, as some have said. How could I? My blog post might have reached a few hundred readers. Maybe. I said that I wouldn’t spend money or devote any more time to writers and publications that participate in such nasty reviews. I didn’t ask anyone to join me.

After others linked to “Writer-on-Writer Crimes” and shared it online, I received many friend requests and gained new followers across the social media outlets I use, so many that I spent a lot of time on Sunday and Monday reading and answering other people’s comments about this. I have to wonder: Did I somehow gain something from wading in? At least a few people told me they bought my book because they liked the post. Writers I admire but don’t really know wrote to say they’re reading Naked Summer and enjoying the stories. And if I could gather for two weeks each summer the more than two-dozen top-shelf writers who have written me privately to thank me for the piece, Bread Loaf and Sewanee would no longer be necessary. I could replace them with the Andrew Scott Summer Writers Conference©.

You can send your money here.

[1] Ford’s comments (re: author/characters=master/slaves) were offensive, and I’m so often disappointed by the things he says, despite loving several of his books. Whitehead’s an engaging writer, so his review has its pleasures, I suppose, though Ford’s comments seem to be the impetus, which means he didn’t approach the book on its own terms. The review’s ending is sharp—one of the all-time good barbs. Whitehead’s review got people talking, long before Facebook and Twitter made it easy to fire up readers and writers. I heard about it in a bar, for instance, several days after the review appeared. There’s no doubt it boosted an already promising writer’s career and profile, but re-reading the review now, it’s easy to see that Whitehead’s self-deprecation eases his scathing approach.

August 18, 2012

Writer-on-Writer Crimes

A flurry of nasty reviews and other attacks on writers has commanded my attention of late, enough to make me consider—or reconsider, in some cases—the reasons for such behavior. The motive is usually ladder-climbing or other forms of posturing. Often the goal is to assert that one writer’s aesthetic is more valuable than another writer’s. A particularly nasty book review gets people talking. On its face, this might be called “buzz,” but it only works to raise the reviewer’s profile if we let it.

I promise to eventually address William Giraldi’s New York Time Book Review piece about Alix Ohlin’s novel and story collection, which were simultaneously released this summer. But let’s remember the context surrounding this review.

Start with Jacob Silverman’s Slate article about “the epidemic of niceness in online book culture,” which claims that Twitter’s “water cooler” vibe turns writers into champions of each other’s successes while dulling our critical capabilities.

We’ve also seen attacks on two successful writers, Cheryl Strayed and Joshua Ferris, masquerading as personal essays with overtures meant to reveal how the writer-attackers have changed or learned something useful from the negative feelings they harbored; those negative responses are, of course, shared with potentially thousands of readers online. Jealous writers/reviewers/commenters want it both ways. They want to be known, but not despised. I have provided the links, but I will not share their names. If you read these, please forget their names immediately.

And let’s also remember the unfolding circus around the review of Patrick Somerville’s novel.

It’s no secret that reviews can be scarce, even for successful, accomplished books. Even the most talked-about titles rarely score more than 20 reviews in the traditional, known outlets. Most writers now hope for only a handful of reviews in newspapers and magazines. We are more likely to see comments on Goodreads or Amazon, many of which are essentially anonymous. Culture-focused websites—Salon, Slate, and The Rumpus—provide a necessary forum for reviews, and some book-related blogs offer smart criticism.

But it’s not enough. I think most writers would welcome an explosion of smart, thoughtful reviews in prominent publications, even if it came with a dose of negative reviews. Not all negative reviews are nasty, after all.

Precious space is wasted in newspapers and magazines when reviewers focus on what to avoid, especially when most readers have likely never heard of the author or book. I’m happy to know which movies to avoid, though—studios spend millions of dollars on marketing and sometimes use intentionally deceptive tricks in the trailers, so encountering an informed response is important, even (or especially) if its negative. Hollywood players loom large in our culture, which makes them easy targets for our snark and derision. We can forget about the individual artists who collectively make a piece of cinematic art. I enjoy reading a harsh review of a film, especially if the reviewer’s intelligence matches the meanness. I’m thinking here of everything from Anthony Lane’s enduringly hilarious and formal takedowns—my favorites tackle Battlefield Earth and Mission Impossible 2—to Roxane Gay’s informal dispatches from her weekly trips to the theater.

But it’s different with books, isn’t it? No literary novel or story collection has that kind of marketing push. We aren’t bombarded with TV commercials for books, and print ads, which can be expensive—full-page ads can cost more than $40,000, while a full centerspread fetches closer to $90,000—are typically saved for book-centric publications such as the New York Times and the New Yorker. Such preaching to the choir matters, but it’s hardly a way to sizably boost the appeal of literature. Only the largest publishers can afford these high rates.

I’ll never read all of the good books other people think I should. I won’t finish the roster of books I do plan to read, and that list always grows, never shrinks. I keep trying.

I did read and enjoy Cheryl Strayed’s Wild, which received a major advance and corresponding marketing effort long before Oprah came along. Its marketing support can’t compare to even the shittiest Hollywood marketing budget. In his smart and engaging response to Giraldi’s piece, J. Robert Lennon argues that “the literary world is basically a small city. We could maybe all comfortably occupy Madison, Wisconsin. And so a book review is not read in a vacuum: when you angrily eviscerate somebody’s work, you are shitting where you eat. It is important both to support each other and criticize each other, and to find ways to do both respectfully and constructively.”

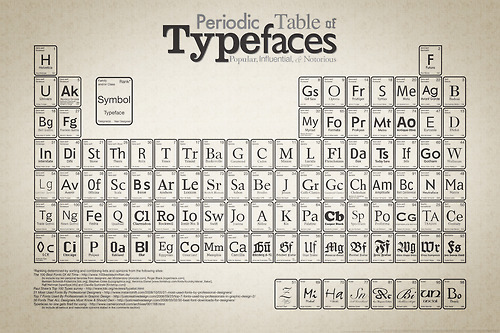

If “the literary world” excludes “regular” readers—if it really just means other writers, editors at literary journals and magazines, editors at presses both small and large, agents, publicists, sales forces, independent bookstore owners and big chain bookstore employees, distributors, professors and students in M.F.A. and Ph.D. programs in creative writing, book cover designers and typesetters, and the rest—then I’ll go a step beyond Lennon and suggest that the literary world might fit into an even smaller college town. Think Bloomington, Indiana.

We are not an army. We are small potatoes. That’s a cliché. Fine. I will be specific: We are Peruvian purple fingerlings.

Negative reviews can be useful. Benjamin Percy examines Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue in the current Esquire. J. Robert Lennon’s guidelines for writing a negative review are exemplified in Percy’s piece, which runs a full page in a periodical that isn’t devoted to books. Percy provides context with “a little fucking humility,” as Lennon says, and it’s clear Percy admires at least two of Chabon’s previous books. He is balanced in his discussion of Telegraph Avenue, the novel he finally deems “a Michael Chabon version of The Corrections.” You get the sense, as you should in all negative reviews, that Percy wanted Telegraph Avenue to succeed.

Authors aren’t supposed to respond to negative book reviews. But it’s hard, isn’t it? Especially when the piece in question isn’t exactly a review of the book. I only encountered the piece about Cheryl Strayed when it appeared on my Facebook news feed a few days later. Cheryl had commented on this post, Facebook said. The writer hoped she and Cheryl could remain Facebook friends. Cheryl, to her credit, treated the post and its author with far more restraint and grace than I would have, though in true Cheryl/Sugar fashion, she didn’t flinch from the truth, either. If you read the piece (and you don’t have to, remember), you’ll see that the writer (I’m not sharing her name on purpose) is really trying to pull herself up, somehow, by making sure you understand she is just like Cheryl in so many ways, and therefore maybe perhaps sorta kinda deserves your attention, too. One major difference not mentioned: Cheryl has never publicly pummeled another writer to get ahead or score points with readers or potential readers.

Which brings me back to Giraldi’s piece about Alix Ohlin. The review fails on every level.

The review is not as sharp as Giraldi might wish; it’s often impenetrable. This is what Giraldi considers good prose. After all, he wrote it.

He cherry-picks examples of Ohlin’s less-than-stellar prose, using only bits and pieces, never a full paragraph. Without context, I will not pan a writer’s use of clichés.

His argument attacks what is called “psychological realism” in passionate defenses of differing aesthetics. Alix Ohlin’s books provide an opportunity for a rhetorical demonstration Giraldi has likely been waiting to make for some time. Her books are not the point.

Always note to whom a writer compares himself, explicitly or implicitly. Here, Giraldi implicitly juxtaposes himself with Cervantes, Bellow, Pound, et al.

The review has a factual error. He calls Inside “Alix Ohlin’s sophomore effort,” but Inside and Signs and Wonders constitute her third and fourth books, which makes one of them at least a junior effort. This language is so high school, as is the review.

The comparison to Danielle Steele is a reviewing cliché. I mean, we all agree that Danielle Steele sucks, right? I’ve never read her work, but we can all safely assume it’s shit, since we’ve been told that so many times. Also, because it’s popular. Giraldi’s comparison makes me wonder if no male writers exhibit these traits, and if the “bad” writers most commonly referenced in reviews are disproportionately women.

The stories that are “faintly fabulist” or present a kind of “Borgesian fever dream” in Signs and Wonders are predictably praised. Division and classification can be useful. It sounds like a diverse collection, but Giraldi only likes the ones that cross into his preferred territory. Charles Baxter calls this “owl criticism” in an essay available online. It means, basically, that a reviewer who doesn’t like owls shouldn’t use that fact as the core response to a book about owls.

His mention of “women’s fiction”—which he puts in quotes—is meant as a defense against anyone who might think this review is unnecessarily harsh solely because Ohlin is a woman, or because she writes about the domestic. Giraldi, like the writers jealous of Strayed and Ferris, respectively, also wants it both ways. The reviewer dost protest too much.

He unfavorably compares Ohlin to Mavis Gallant and Alice Munro, saying she doesn’t belong in that group—“not because of her leaden obsession with pregnancy, dating and divorce, or any inherent bias in the publishing industry, but because her language is intellectually inert, emotionally untrue and lyrically asleep.” Comparing Ohlin to two other Canadian writers with vaginas, Giraldi again reveals his classification methods. But Gallant was born in 1922. Munro was born in 1931. Ohlin also compares unfavorably to Chekhov, Poe, and Borges, but that goes without saying. After all, they’re dead and had penises.

Finally, Giraldi relies on “John Erskine’s immortal coinage” about “‘the writer’s “moral obligation to be intelligent,’” which seems redundant; by this point, it’s clear that Giraldi thinks Ohlin—if I may exhibit “the complacency of the au courant”—is fucking stupid.

Sigh.

I’m so tired of this. Aren’t you? Keep in mind that most of the world doesn’t care about writers and our petty problems. Peruvian purple fingerlings, people! I’m tired of encountering essays and articles that wish to knock down more experienced or successful authors. But here’s the thing: I only know of Anis Shivani (to name one example) because he wants to rile the tiny Bloomington-sized literary world. Every town has a few idiots. Sometimes they run naked down Main Street. We try to keep them from hurting themselves or others. We want to ignore them, but there they are, naked again in the center lane.

Here’s what I’m going to do. I will no longer give my time or money to fiction writers who work to boost themselves at the expense of other fiction writers.

For several months, William Giraldi’s Busy Monsters has been on my Amazon wishlist, which I use to keep track of the books I mean to read, even when I don’t shop at Amazon. I could never quite decide to buy his novel, for some reason. He and I were part of the Newburyport Literary Festival this year. His presentation conflicted with my schedule that day, and I was bummed to miss it. I must say, I no longer regret missing his talk, and I’ve removed his novel from my wishlist, since I’m not going to buy it. I’m not going to read it. I’m not going to read any of his books in the future. I will never subscribe to AGNI, the journal he edits, or even visit its website. Not because he was mean to a writer I don’t know, but because his kind of criticism poisons the well, not just the person, and our little town can’t afford a new treatment plant.

Alix Ohlin’s books were also stuck next to Giraldi’s on my wishlist. After his review appeared, I purchased hers.

One Story just published a story by another writer known for a recent nasty review. This is the only issue of One Story I have ever tossed into the recycling bin. The website that published this particular author’s negative review—which I refused to link to above—is something I no longer read. After letting my subscription to the Sunday Times lapse this summer, I now have decided not to renew. Besides, I felt like a fool for paying good money to read on Sunday what everyone else read online for free on Thursday.

No one will notice, and my actions won’t really matter to the individuals and entities involved. This choice won’t matter to anyone but me. But if I’ve learned anything from these nasty reviews, it’s that everything I do should really be about me, anyway.

August 16, 2012

August 7, 2012

Press 53: 5 Questions, 3 Facts

Welcome back to the working week, and to ease you into it, we’ve got Andrew Scott, author of the short story collection Naked Summer, telling us about the influence of comic books and how he never (!!!) gets writer’s block.

P53: What do you do to combat writer’s block?

July 31, 2012

"Living or dying by the clock is a miserable way to do something you love."

- Barb Johnson, author of More of This World of Maybe Another

Andrew Scott's Blog

- Andrew Scott's profile

- 9 followers