Andrew Scott's Blog, page 43

January 20, 2012

"Last year I brought back with me from the island of Ceylon a male mongoose (defined in Brehm as..."

- Anton Chekhov, "To The Management of the Moscow Zoo, 14 January 1892, Moscow"

January 17, 2012

Where Do You Buy Your Books?

Last week, I missed Borders in a way I never have before. The former location in downtown Indianapolis still makes me sad. It was a beautiful space. Did your Borders look like this on the inside?

Or like this on the outside?

Victoria and I loaded up on books during the chain's final week. We even bought a couple of signs to hang on our dining room wall ("Graphic Novels" and "Literature"). We bought so many books that we also had to buy new bookcases, which meant we had to redecorate the living room. We liked our new stuff, but felt kind of bad about how we acquired it.

I've been to Barnes & Noble a few times in the last couple of months. Borders had a better selection, overall, though I like B&N's Discover Great New Writers shelf, which seems friendly to story collections.

No, the reason I went out to B&N last week was to see if I could buy a calendar for our office. We've got a tradition: Each year Victoria gets a certain calendar that features chickens, and we take it to our campus office. We forgot to buy it before Christmas this year, since we were excited about our trip to Puerto Rico. Anyway, I bounded out to B&N, thinking I could find the calendar, maybe even at a post-holiday markdown.

Only B&N didn't have calendars. Not really. Just a table full of crappy Colts calendars even Peyton Manning's mom wouldn't touch.

I was kind of bummed, even though I scored this DC Comics Poster Book I'd had my eye on this summer, now at 75% off.

It seemed like Borders always had calendars. Shelves and shelves of calendars, often well into the new year. I began to get mad at B&N for not having calendars. Why couldn't B&N be more like Borders?

Then I remembered that having calendars—and far too much shiny physical media, such as their overpriced DVDs—was part of what did in Borders. B&N is actually more of a bookstore than Borders was, percentage-wise, even if Borders had a better selection and a greater number of titles. Or, to put it another way, Barnes & Noble has less shit that isn't books.

I'm supposed to take my business to an indie bookstore now, right? When you search for my zip code in the indie bookstore finder, most of the stores listed no longer exist, primarily sell books for children, or are actually comic book stores. Indianapolis has a great many chef-owned restaurants, but we also have chain restaurants galore. People don't really care where they buy their books, just like most people don't care where they get their food or where it comes from. Most readers, I mean. Only writers, editors, and other publishing-related people care about these details with a passion. They (we) are like foodies, a small but vocal minority.

Simply put, I don't give indie bookstores the free pass they've supposedly earned for their dedication to authors and readers over the years. Booksellers, in general, need to become more responsible about the well-being of their economic ecosystem. Books were first made returnable during the Great Depression, as publishers sought to keep their only viable sales outlets afloat during lean times. But that practice has been kept in place for more than 80 years now, so that booksellers are the only retail industry allowed to return unsold product, in practically any condition, for credit. If Kroger orders too many bananas, they're stuck with them; they can mark them down, try to make back the cost, at least, and they can learn to order fewer bananas next time. Kroger can't simply send the bananas back to India or Brazil for credit.

When it comes to the book business, this practice allows bookstores a great deal of protection. It's low-risk, and even still, the industry struggles. Returns generate money for the printer of the books, of course, and UPS/USPS or other shippers. Sellers of packing tape make out all right in this arrangement. But publishers often don't. Authors don't. The smaller the press, the more they are hurt by this practice. And if you don't accept returns, you're not ever going to have a breakout hit because bookstores won't order titles, generally, that are not returnable.

Further, when authors or publishers try to reason with a bookseller — to ask the store to order 10 copies they might actually sell, rather than order 50 copies even though they'll likely return 40 of those copies in six months — they're scoffed at like they're crazy or inexperienced or don't really understand how this all works; how could only 10 copies ever be better than 50?

I've had some great experiences with independent bookstores. I read at Carmichael's in Louisville last year, and Get Lost Bookshop sold books (and had me sign the extra copies for their store) when I read at an art gallery in Columbia, MO. I'd love to transplant a store like Von's Books to my neighborhood. But right now, there isn't a local option I'm happy with. (For Indy readers: Yes, I know the one in Broad Ripple; no, I don't like it.)

There are big indies, like Powell's. I generally like Powell's, but I don't necessarily want to throw tons of money at indie bookstores that also make a lot of money from the sale of used books. Authors and publishers don't make money from used books. Readers save money, used bookstores make money, but authors and publishers don't. Plus, for whatever reason, Powell's has my book listed at higher than cover price, which is just weird. Weird!

This won't make some of the do-gooders happy, but it's true: Amazon is friendlier to small press publishers than most independent bookstores. Their e-book agreements share more money with the publisher/author than the Google arrangement, but indie stores have aligned with the Google platform so that readers can buy e-books from local retailers. Why must authors/publishers and booksellers be at odds?

Not that Amazon is perfect. Far from it. With their fight to avoid paying sales tax and their often horrible working conditions (most warehouse employees are temporary), not to mention their highly publicized—but often inaccurately reported—effort last month to market their price-comparison app, Amazon is like a giant who wants to dance but instead crushes the entire village.

But, damn, I wanted that chicken calendar, you know? So I ordered it from Amazon while writing this post. It was only $6.99. Free shipping. We'll have it in two days.

January 11, 2012

Do we need book awards and lists to celebrate the year's "best" books?

I've given this a lot of thought lately, because it's that time of year and because this is the first time I've had a horse in the race—a book of my own.

This year's finalists for The Story Prize were announced this morning. The Story Prize is a tremendous and important effort that shines a bright light upon story collections, and Larry Dark is an advocate-warrior for short fiction. I like Larry, and if his work for The Story Prize and as the former series editor of The O. Henry Prize Stories is any indication, we are kindred readers.

Here are the finalists:

· The Angel Esmeralda by Don DeLillo (Scribner)

· We Others by Steven Millhauser (Alfred A. Knopf)

· Binocular Vision by Edith Pearlman (Lookout Books)

Does choosing these three particular titles as finalists for a prize designed to honor the short story and short-story writers ultimately devalue the singular, stand-alone story collection?

Imagine Queen's Greatest Hits or Sam Cooke's Portrait of a Legend, 1951-1964 winning the Grammy for Album of the Year. Here's an idea: Selected Stories, New and Selected Stories, and Collected Stories should not be considered for the Story Prize (TSP).

TSP's website states: "The idea that the short story is a beginner's form, one that novice writers cut their teeth on before turning to the more ambitious work of writing novels, is a common misconception. This year's finalists for The Story Prize show that—to the contrary—top fiction writers often remain devoted to the demanding form of the short story throughout their careers."

It's hard to argue that Don DeLillo is "devoted to the demanding form of the short story" since this is his first collection. The nine stories in The Angel Esmeralda, written over three decades, emerge as a de facto Selected Stories. While DeLillo has written short stories, he's not exactly a short-story writer, is he? If I may continue my shaky Grammy analogy, this is akin to Jethro Tull being nominated—and winning!—Best Metal Performance in 1988. Don DeLillo, like Jethro Tull, is not metal.

Short stories are metal. Flash the horns and all hail black metal: \m/ \m/

[Sorry about that.]

Steven Millhauser has published many novels and story collections. I admire many of his stories. But like DeLillo, Millhauser doesn't need any more attention. He won the Pulitzer Prize, for Pete's sake, and DeLillo has won the National Book Award. Only about 35% of We Others: New and Selected is devoted to new stories. If you already like Millhauser's work, do you really want to pay nearly $30 (assuming you avoid Amazon.com) for a book with only 144 pages of new fiction? By contrast, my book is about that long and costs $14.95; a reader can buy my book and another book of stories for the same price. And if you've been reading Millhauser's stories for years—"The Knife Thrower," anyone?—why would you want to pay twice for the 65% of the book you already have elsewhere on your bookshelves?

Edith Pearlman is clearly "devoted to the demanding form of the short story," and her three previous books, all story collections, found publication because of awards designed specifically to aid writers like her, "a career short story writer whose brilliant work has only recently captured much-deserved attention." Binocular Vision was also a finalist for the most recent National Book Award. It includes 18 stories found in previous books, three stories never collected during that time, and 13 new stories. Pearlman has published more than 250 short stories during her career, and this book is designed to showcase that she's been here all along, quietly chipping away at this good work. While she certainly deserves this recognition, it's a bit disheartening that it comes within months of the National Book Award's attention; this selection has the feel of a student who merely echoes a classmate's comments without contributing anything new to the discussion. Of these three finalists, I hope Binocular Vision is chosen for the Story Prize and its $20,000 cash award. Maybe it's Pearlman's year.

The Story Prize does nearly everything right, and it awards more money to fiction writers than the National Book Award Foundation. Its open policy means that Larry Dark and Julie Lindsey, an advisory board member, encountered "a field of 92 books that 60 different publishers or imprints submitted in 2011." While the $75 entry fee is pricey for small-press authors and publishers, the fees generated don't come close to covering the cost of the awards—$30,000—given to three writers each year, which means Larry, Julie, and anyone else involved work hard to raise the funds that support this worthwhile endeavor.

Perhaps the Story Prize should consider splintering its efforts into two categories. The first might honor a writer's entire career in the short story form. The second category could honor a stand-alone collection of stories, such as last year's winner, Anthony Doerr's Memory Wall.

I didn't speak up when Tobias Wolff (2008) and Mary Gordon (2006) each won The Story Prize for their New and Selected Stories, but only because the other finalists were singular collections. This trio of books is no doubt excellent. I'll buy all three soon enough. But my sincere hope is for The Story Prize to rise to even greater prominence, to be the equal, perhaps, of the National Book Awards in terms of its reach and influence, which can help boost story collection sales. I think putting its attention back on singular story collections will exponentially boost The Story Prize's relevance. It's not like there weren't excellent contenders this year.

Every single list that fails to mention my story collection is a personal affront that I will never forgive. I don't believe my book made a single list of this kind; if it did, then Google Alerts has also failed me. But please know this: If you published one of these lists online and didn't include Naked Summer, I hate you at least a little bit. And I also hate you, Google Alerts.

Off the top of my head: Michael Kardos, One Last Good Time; Seth Fried, The Great Frustration; Valerie Laken, Separate Kingdoms; Caitlin Horrocks, This Is Not Your City; Patricia Henley, Other Heartbreaks; Shannon Cain, The Necessity of Certain Behaviors; Shann Ray, American Masculine; Alan Heathcock, Volt; Daniel Woodrell, The Outlaw Album; Alethea Black, I Knew You'd Be Lovely; Steve Almond, God Bless America; Ben Loory, Stories for Nighttime and Some for the Day

January 6, 2012

"I'm only interested in stories that are about the crushing of the human heart."

- ― Richard Yates

January 4, 2012

The Spirit and the Flesh

At times, there's real bitterness in the world of writers and publishing. A few months ago, I read a blog post where dozens of writers — in the post itself, and in more than 100 comments about the post — chimed in to slam on Glimmer Train, a respectable and long-running literary journal that has published many of our best writers and paid all of them for their work. Seriously. Two sisters who aren't writers establish a fiction-only journal, stay in business for 20 years, achieve a circulation approaching 20,000 readers, make their issues available to readers who aren't necessarily writers via chain bookstores, and publish stories that earn numerous selections and honorable mentions in the year-end anthologies. How do those sisters become the enemy?

What was I going to do, jump into the middle of an online argument and try to make my case? Right, because that always works. I have sold four author interviews to Glimmer Train, and they've paid for the reprint rights to several others, so you can say that Glimmer Train has paid for the appliances in my kitchen. There's always something cooking in this house, but those online commenters won't be invited to dinner. As best I can tell, their chief complaints about Glimmer Train are the quality of the fiction they publish — which boils down to readers' preferences, ultimately — and the journal's use of contests, as if the writers paying those contest fees are somehow held hostage and forced to submit.

What was I going to do, jump into the middle of an online argument and try to make my case? Right, because that always works. I have sold four author interviews to Glimmer Train, and they've paid for the reprint rights to several others, so you can say that Glimmer Train has paid for the appliances in my kitchen. There's always something cooking in this house, but those online commenters won't be invited to dinner. As best I can tell, their chief complaints about Glimmer Train are the quality of the fiction they publish — which boils down to readers' preferences, ultimately — and the journal's use of contests, as if the writers paying those contest fees are somehow held hostage and forced to submit.

Here I am, though, caring about what these knuckleheads have to say online. It's pretty easy to stir up a mess of attention by publicly slamming on those who are successful. It's also too easy. Lately, though, I've been wondering how bad attitudes and public bitching helps writers promote their work, or lay a foundation to bring in future readers. A fiction writer cranks out a piece for the Huffington Post about writers he thinks are overrated, mostly as a way to make himself feel better, or to get back at his "enemies," as he sees them. Does that somehow help him sell more books, or build a reputation that helps his career as a fiction writer? Does it lure new readers to contemporary literature? How could it? Yet every time one of these articles appears, thousands and thousands of readers — including too many writers — click through each name on the list, generating hits and additional ad dollars for HuffPo, enough for the editors to decide to run a similar piece in the future, since it was so profitable the first time.

All writers are small-time, though, aren't we? Some are more small-time than others, granted, but wouldn't most writers be thrilled for their books to sell a hundred thousand copies? If only a hundred thousand people see a movie in its opening weekend, the movie is considered a flop. Even The Da Vinci Code, which sold more than 80 million copies, is dwarfed by the size and reach of other popular storytelling media; The Dark Knight, after all, sold more than 80 million tickets in its first 10 days.

I'm not one for resolutions at the start of a new year, but in 2012 I plan to avoid the literary/culture websites that try to build up their own contributors by means of tearing down others. Or maybe I should just take what Tony Hoagland calls "the shortcut / between the spirit and the flesh, / and punch someone in the face" and get on with my day.

January 3, 2012

More Posts to Come

I'm planning to write a new post every week in 2012, mostly about writing and publishing. If I don't stay focused on book-related topics, I'll become one of those bloggers who froths at the mouth about sports. That said, Drew Brees should be the MVP.

October 16, 2011

Journal & Courier Interview

Journal & Courier is no longer available online. Here's the reprint.>

What kind of presence does the short story have in the 21st century?

The short story is still alive and well. In fact, there are more story writers of excellence now than at any other time in history. And, given our on-demand culture, I'm hoping short stories will continue to find even more readers.

What are your thoughts on the Amazon.com initial rankings of your book, especially with Stephen King just behind you? How is the book doing now?

My publisher came up with a "Get Naked on Amazon" campaign, and we tried to get as many people as possible to buy it on June 1, which brought extra attention to the book. For a day or two, it was selling better than Stephen King's most recent book, which is also a story collection, and it stayed in the top twenty for over a week — long enough for my wife to screen-capture it, anyway. I'll take what I can get.

How did you use Greater Lafayette in your stories?

Tippecanoe County permeates every story in the book. "All That Water" is set on the Tippecanoe River. "Tornado Light" features a deadly car crash along River Road and name-checks Lincoln Cafe. I've fictionalized certain elements, like the high school and some of my former places of employment. A book by Don Kurtz called South of the Big Four, which is probably my favorite novel (one I hope to adapt into a screenplay soon), is set in the farm country north of Lafayette, and it gave me permission, as a young writer, to dig around my own fertile soil for fiction. I've never looked back.

It seems you are taking a multimedia approach with your book. Is this necessary for a new author in 2011?

For promotion, it is absolutely necessary. I like connecting online with readers and other writers. As someone who creates characters and deals in language, it's natural for me to create an online presence. It's just another persona. And high school classmates have been buying the book and sharing the links to Amazon on Facebook, which is nice.

How does it feel to have your first published book? Are you working on a follow-up?

Such a relief, actually. I worked on this book off and on for 10 years. Some of the stories date back to 1998-1999. I wrote other pages during the intervening years, including graphic novel scripts, and they're all in development. I also wrote a feature-length screenplay and one short screenplay. I'm now working on a novel set in Lafayette, as well as a linked story collection at least partially set here. I'll write about other places someday, but not yet.

Which is your favorite story in Naked Summer and why?

I don't have a favorite, but I'm happy that the title story, which is too long to publish on its own in a literary journal or magazine, is finally available to readers.

October 1, 2011

Ten Commandments for Fiction Writers

website.>

1. I am Literature, your God, and you shall have no other gods before me, but, in the end, it's just words on paper, so don't go crazy in your effort to be as good as Virginia Woolf, Ernest Hemingway, or any other writer who committed suicide. Many things are more important than Me. And you.

2. Thou shalt not make for yourself an idol, especially your editor or thesis director, who is just another person struggling to put words and ideas together in a way readers might care about.

3. Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord in vain, if only because you're a writer who can find a better word. Salinger's estate has copyrighted "Goddamn," anyway, you phoney.

4. Remember the Sabbath, especially Black Sabbath, or whatever kick-ass music will keep you from living in your precious little head for a few hours.

5. Honor thy father and mother, but don't ask them (or expect them) to read your work. And if they're assholes, don't bother honoring them.

6. Thou shalt not kill, not even your darlings. Remove them if necessary, but keep them in a folder. You may need them someday.

7. Thou shalt not commit adultery, but don't be afraid to dabble in another genre or art form. Spread it around, babies. Do something else now and then.

8. Thou shalt not steal, unless it's from Shakespeare, which is officially sanctioned.

9. Thou shalt not bear false witness, but please recognize that work can also be play, and some of the most engaging narrators in the history of literature are unreliable.

10. Thou shalt not covet, but if you do, kudos to you, because all fiction is really about desire, and aren't you lucky to understand how that works?

September 27, 2011

Try, Try Again: Rejection and Persistence

Two months before I moved to New Mexico to study fiction writing with four writers I deeply admired, I submitted a short story to magazines for the first time. Knowing a response would take a while, I listed my future address on the SASE. I had only written one story good enough to send out. A shocking coincidence: It was the only story I had ever seriously revised.

To kickstart the writing career I desperately wanted, I dutifully prepared five copies of the manuscript, personalized the cover letters, evenly sealed the manila envelopes, and worried that my stamp selection — Daffy Duck angrily eyeing the mailbox — might suggest that I wasn't serious enough to be considered.

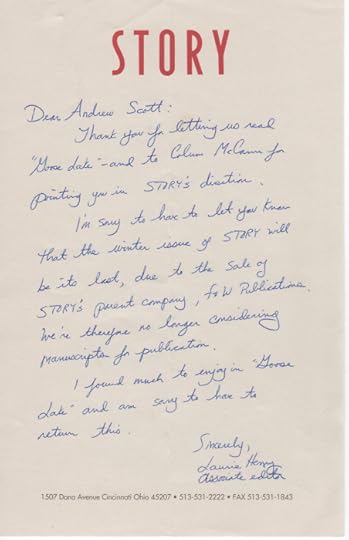

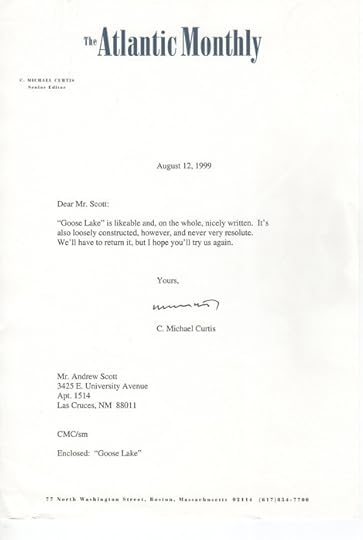

I sent the story to the New Yorker, the Atlantic, Story, Zoetrope: All-Story, and DoubleTake. I knew enough to have read each of these publications a few times. They were available at the recently opened Barnes and Noble in my hometown. I followed the submission guidelines closely. At the end of the summer, on the day my girlfriend and I arrived at our new apartment in Las Cruces, four rejection letters waited for me in the mailbox. The fifth arrived a few weeks later.

I expected rejection. Here's what I didn't expect: Only two were form rejections.

A year before, I had attended a week-long writing workshop in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where I befriended Colum McCann, whose third book had just been published. A couple of his stories had appeared in Story, my favorite magazine, so in my letter I said that Colum had told me to submit. Which wasn't exactly true. He had encouraged me to start sending out my work, though, and clearly he considered Story to be a good magazine. A little white lie wouldn't hurt.

An editor at Story had written — by hand — a personal response: I like your story, but we're going out of business.

The Atlantic sent a personalized letter, too, something I now know was a common reply to many writers enrolled in M.F.A. programs. While the letter was brief, it was signed by legendary editor C. Michael Curtis, who had helped better some of my favorite stories.

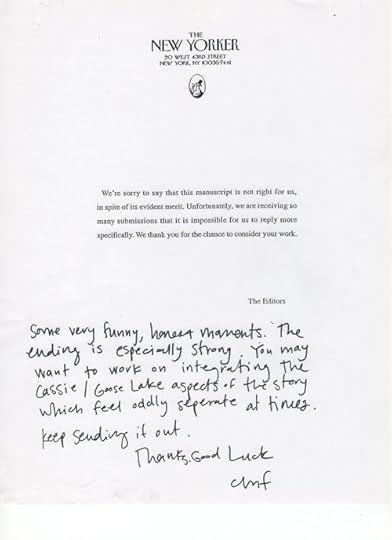

But the one that really surprised me was the note at the end of theNew Yorker's letter. I had been told to not even expect a reply, as the slush piles towered in their offices. The form cited the story's "evident merit," which was helpful, as its merit wasn't evident to me, while the handwritten note praised the story's honesty and humor, as well as its ending.

Rejection has never felt so good.

I would love to say that one of these five publications later snatched up a different story of mine, or that the story then called "Goose Lake" eventually found its way into a respectable literary journal. But that never happened.

Not that I didn't try. In that first semester of grad school, Antonya Nelson showed us her record-keeping system, which featured index cards for each magazine or journal, and an index card for each submission. Do I have to say that I promptly ran out and bought some index cards, along with a little box to organize them?

Given that I would submit 416 times to various print and online journals before my first book was published, I soon switched to Excel within a year or two — so cold and corporate, yet so sortable and searchable. The simple act of record-keeping let me track my repeated failure across the years, which led to the most important lesson I learned about the business of writing: Your work will usually be rejected, and it will be hard to "break in," and it may never get any easier. But if you don't believe in yourself, no one else will. And if you don't keep writing while facing down rejection, you'll never get past it.

After six years and 252 submissions, one of my stories was accepted for publication, but not in a literary journal. I began corresponding with an independent publisher from whom I'd purchased a chapbook written by a friend. I asked him how he found his authors. He explained, then asked if I had something I wanted to submit. I sent him three stories, and he chose to publish one of them, "Modern Love," as a stand-alone chapbook. My best friend did six pieces of artwork for the chapbook, including the cover. It's truly beautiful for reasons that have little to do with me.

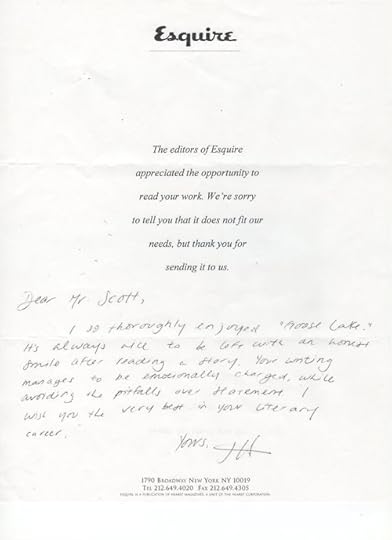

I gave the chapbook to several writers I admired, thank-you gifts for their good prose. One of them, Tom Chiarella, who writes forEsquire and served then as its fiction editor, liked what I sent him, so he mailed a cocktail napkin and asked me to write a story on it, which was later published as part of a series on the magazine's website. In the weirdest way I can imagine, my fiction found a home at Esquire.

Since 2008, I've published seven short stories, all but one of them online. While my fiction has never appeared in a print journal with a wide circulation, one publication has often led to another. One editor read, but didn't buy, my chapbook at Powell's in Portland, Oregon, then invited me to submit a story to Superstition Review, a journal in Arizona. One of the readers at Booth read my story published by Hobart, then asked me to submit. My acceptance rate has skyrocketed, partly because these stories are better now after dozens of revisions. But it's also like dating: You might never be more attractive than when you're in another's arms. One acceptance will often lead to more.

My book of stories, Naked Summer, was published in June. The first story I ever sent to magazines, now called "Lost Lake," was submitted 81 times between July 1999 and December 2010, when Press 53 offered to publish my collection. Though "Lost Lake" was never accepted by a journal, I couldn't — wouldn't — give up on the story.

Its new home begins on page 53. I hope that New Yorker editor still likes the ending.

August 29, 2011

Here are the rejection letters mentioned in my Beyond the...

Here are the rejection letters mentioned in my Beyond the Margins post. The rejections from Story, the Atlantic, and the New Yorker are for the first story I ever submitted. The fourth rejection, from Esquire, is for the same story, but after three years of revision.

Andrew Scott's Blog

- Andrew Scott's profile

- 9 followers