Andrew Scott's Blog, page 42

March 24, 2012

"What’s so exciting and terrifying about the writing process is that it really is an act of..."

- Andre Dubus

"What's so exciting and terrifying about the writing process is that it really is an act of..."

- Andre Dubus

March 20, 2012

Endorsement Anxiety

First problem: the word itself, supposedly coined by a humorist in the early 20th century. More than a hundred years later, the joke's still on us. As a noun and a verb, "blurb" belittles the sweeping majesty of literature. Or maybe it limns entire narratives in a handful of words. But can a blurb be a page-turner?

Every author I know has asked for a blurb or been asked to provide a blurb. Nearly a decade ago, in a short essay about this fundamental and unquestioned element of book publishing, Steve Almond said, "Listen: when someone asks you to blurb a book they are paying you a huge compliment. At the very least, they are saying to you: 'I believe your name will help me sell books.' But more than likely they are asking you because they know and admire your work. These are not people to shit upon."

The rest of Almond's piece is sharp, insightful, and funny, like much of his writing. But why do we always insist that blurbs help sell books? The publishers and editors I've talked to about this topic admit that they don't think blurbs boost sales. Anecdotally, at least, most readers aren't so easily swayed by what we all recognize as the act of one writer doing a favor for another writer.

Yesterday, I talked with my friend Jared Yates Sexton, a writer whose debut story collection, An End to All Things, will be published later this year by Atticus Books. He's now making decisions about the possible blurbs for his book. He has a few inclinations, including one famous author we admire who, he admits, is a long shot. After much to and fro, we decided that blurbs don't really help the book, but they can help the writer's positioning within the world of other writers. At one point, I said that blurbs are like gang tattoos — useful when you end up in prison and need to let your crew and enemies know with whom you roll[1].

As a younger reader, I noted how blurbs revealed the intricate network of contemporary writers in useful ways as I randomly grabbed books at Barnes and Noble. It's how I discovered some of my favorite books and authors, moving both forward and backward across the last century.

Another writer (and former friend)[2] thinks that attending Sewanee or Bread Loaf is a built-in way to get a blurb from a famous author. They basically have to give you a blurb when you study with them there, this writer told me. I am not so sure.

When it came to asking for endorsements (my preferred term) for Naked Summer, I decided not to ask my former teachers and mentors. Hadn't they done enough for me already? Not everyone shares my mindset. In fact, sometimes it's the only option for new authors. Greg Schwipps, author of What This River Keeps, says: "No one likes asking for a favor as big as a blurb, and ideally, someone offers. But if you have to ask, is that really so bad? Haven't you been asking your writing mentors for favors the whole time you've known them? Read this, read this again, write a rec letter, please. What's one more?"

Schwipps makes a good point. None of the excellent writers I studied with have ever said no when I've asked for help. However, writers who also teach often have to go back to those mentors again and again for letters of recommendation—for teaching positions, residencies, and the like[3]. I wanted to leave a little something in the well.

Michael Nye, author of Strategies Against Extinction[4] (forthcoming) and managing editor of the Missouri Review, asked his mentor, Melanie Rae Thon, for a blurb. "She wrote a paragraph about my story collection that I felt in my chest. She somehow managed to say, with absolute precision and clarity, what she admired about my writing. And she picked up on something so unconscious in my mind, something that I feel moves me to write but which I cannot articulate, that I started to tear up. Honestly. It was as if the most perfect reader had been moved, had understood, had felt my writing in a way that I imagined could not possibly happen with another reader. The blurb means something to me."

Damn. A blurb can be an axe for the writer's frozen sea within. Score one point for Michael Nye.

I also decided not to ask any writer I considered a close friend[5]. I am also the co-editor of a literary journal, but I didn't want to ask an author whose work we'd published.

During a cross-country trip to the AWP conference last year, I debated the relative pros and cons about the process with another friend, Bryan Furuness, whose novel The Lost Episodes of Revie Bryson will be published later this year. He said I was thinking too much[6]. Clearly, I had issues about this process. But I'm not the only one.

Michael Nye continues: "I took two shots at 'big' names; one agreed, the other ignored my email. Every writer I asked already knew how gut-wrenching the process is. It's a huge favor to ask, and feels like begging, and none of us are particularly good salespeople. Everyone that agreed to write a blurb did so with enthusiasm, and that alone means a lot to me."

Caitlin Horrocks, author of This Is Not Your City, "found blurb-seeking pretty stressful. The glorious part was reading the lovely things people eventually wrote. But before that came the brainstorming with my editor of the-absolute-most-famous-people-I-have-any-possible-pretense-to-approach, and my approaching those people to often either deafening silence, or the completely understandable plea that they were too busy to read the book. Approaching other readers, like my MFA teachers, with whom I had a clear connection, was much less scary, but I was still very conscious that I was asking for a time-intensive favor. In the end, I was grateful to receive beautiful, generous blurbs from people who could have done a lot of other things with their time. But I still felt like I'd had to spend some weeks crawling around on my belly to get there."

Nobody wants to be made to crawl. No one, as Almond reminds us, wants to be shit upon. I can echo these other writers in saying that the authors who turned me down did so with considerable grace. One, a winner of the National Book Award who wrote a letter of recommendation when I applied to graduate school, admitted that he was now getting several requests a week. Another, a winner of the Pulitzer Prize, wished he had the time, but a new novel and a TV pilot had to come first. A third, a delightful story writer with a perfect mustache, congratulated me and praised the title and shared a nice memory of the campus visit during which we met, but politely conveyed that he only writes blurbs for former students. I then switched gears, asking a writer with only one book who is younger than me; he couldn't imagine why anyone would care about his endorsement.

All of these writers—men, you may have noticed—were kind and respectful when they declined a blurb request. I did not feel shat upon. A fourth male author ignored my request, though he's a shut-in these days, so it was expected. A fifth agreed to provide a blurb, and advised me to keep reminding him about deadlines; I nudged him once, then gave up, because by then I already had three blurbs and no more energy.

The first two authors I asked were women. They agreed immediately. I'm not sure what to make of that, except to say that dudes are dumb and women are awesome, my guiding philosophy since high school. Whatever we may feel about blurbs, they're not going anywhere. Like an author photo someone paid good money for, blurbs are going to hang around for a while.

[1] What is wrong with me?

[2] I am sometimes stubborn and opinionated and hold grudges. Ditto for this writer. Bad combo.

[3] Note to academia, et al.: Letters of recommendation are just really long blurbs and are, by this point, also an unexamined, expected part of the selection process. No one likes to write them. No one likes to read them. No one likes to ask for them. Can we move on from this archaic practice now?

[4] Great title. If blurbs do not sell books, perhaps good titles can.

[5] I didn't really know the three authors who blurbed Naked Summer. Alice Dark and I met only briefly four years ago at AWP. Michael Parker and I hung out at a writers' conference for a week in 1998, though he wasn't my workshop leader, and I later interviewed him for Glimmer Train. I know her much better now, but I'd only just met Elizabeth Stuckey-French a month or so before my book was accepted for publication, though she and I and Axl Rose all attended the same high school—not at the same time, sadly.

[6] Bryan also said I am "not wired right." Reader, he gets me.

February 27, 2012

#AWP12 Schedule

I'm driving up to Chicago on Wednesday for the annual AWP Conference. How nice it will be, just me and 9,500 of my closest friends and frenemies. I'll attend a few panels and hob-nob with my fellow wizards each day. There are tons of off-site events each night, too. Here are a few of the places you can find me, if you're the FBI and/or hope to see me. Press 53 will have a few copies of Naked Summer for sale, too. (Table R6)

I will, from time to time during the week, help Victoria at the Engine Books table (H14). As a reminder, I do not have an official role with her press. Engine Books is 150% pure Victoria. I'm just a supportive (read: awesome) husband, which means I run out for burritos when she's swamped making eBooks, or bring Cadbury creme eggs to help her cope with the mountain of queries. And, yes, help her out with the table when she goes to another city to promote the work of EB's excellent catalogue.

Thursday

Two big events on Thursday night. I might try to attend both. Or maybe I'll go to the book release party for Fires of Our Choosing, the debut by my friend Eugene Cross, and send the Earth-X version of myself to The Rumpus Reads for 826 Chicago.

Friday

10:30 a.m.: I'm moderating and participating in a panel about prose writers who also write screenplays. Happy to be in the company of these awesome writers.

F145. The Hollywood Stint: Prose Writers and Writing for the Screen

(Andrew Scott, Douglas Light, Tom Chiarella, John McNally, Owen King)

Red Lacquer Room, Palmer House Hilton, 4th Floor

Writing for Hollywood has long appealed to prose stylists such as Dorothy Parker, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, and many contemporary writers. These panelists will discuss writing across genres, what's required to write for the screen, how their fiction writing skills aid or hinder their attempts to please Hollywood, their dealings with producers, studios, and television networks, and the changing perceptions about screenwriting within creative writing programs.

7:30 p.m.: Myfanwy Collins and Patricia Henley read at Women and Children First, a great bookstore. 5233 N. Clark St. Chicago, IL 60640

Saturday

10:30-11:45 a.m.: Signing Naked Summer at the Press 53 table (R6) inside the bookfair, which is free to the public on Saturday.

February 23, 2012

LINES FROM "THE PRINCESS BRIDE" THAT DOUBLE AS COMMENTS IN A CREATIVE WRITING WORKSHOP

First, the amazing original.

"Doesn't sound too bad. I'll try to stay awake."

"Hold it, hold it. What is this? Are you trying to trick me?"

"Stop saying that!"

"We are men of action. Lies do not become us."

"Oh, the sot has spoken."

"Friendless, brainless, helpless, hopeless!"

"Do you always begin conversations this way?"

"Look, I don't mean to be rude, but this is not as easy as it looks, so I'd appreciate it if you wouldn't distract me."

"Beautiful, isn't it? It took me half a lifetime to invent it. I'm sure you've discovered my deep and abiding interest in pain."

"So let's just start with what we have. What did this do to you? Tell me. And remember, this is for posterity, so be honest. How do you feel?"

"A trifle simple, perhaps."

"I admit it, you are better than I am."

"Get used to disappointment."

"The battle of wits has begun."

"Truly, you have a dizzying intellect."

"We face each other as God intended. Sportsmanlike. No tricks, no weapons. Skill against skill alone."

"You mock my pain."

"Life is pain, Highness. Anyone who says differently is selling something."

"We'll never succeed. We may as well die here."

"… and thank you so much for bringing up such a painful subject. While you're at it, why don't you give me a nice paper cut and pour lemon juice on it?"

"That doesn't leave much time for dilly-dallying."

"So bow down to her if you want. Bow to her. Bow to the Queen of Slime, the Queen of Filth, the Queen of Putrescence. Boo. Boo. Rubbish. Filth. Slime. Muck. Boo. Boo. Boo."

"The Pit of Despair!"

"I'm not listening!"

"I think that's about the worst thing I've ever heard. How marvelous."

February 15, 2012

Happy Valentine's Day, Sugar

A year ago—my best guess; it may have been before or slightly after, but definitely before the AWP conference in February, where I brought home some Sugar-related swag for my wife—Victoria and I put our noggins together to try and figure out the identity of online advice columnist Sugar (see Dear Sugar at the Rumpus), since this sweet-but-tough dispenser of hard-won wisdom had inexplicably wormed into our conversations each week. The Rumpus website was abuzz with guesses about her (his?) identity, but those writers—and I apologize to those writers, many of whom are friends with Sugar—didn't write as well as Sugar.

Victoria is really good at making sentences, at recognizing syntax, that sort of thing. She once recognized a short uncredited piece in Esquire as the work of our friend Tom Chiarella. From the syntax. Who does that? Freaks of nature who read Brontë books in grade school, I guess.

We had a pretty good idea that Sugar was Cheryl Strayed. I can't remember who first figured it out—probably Victoria—but then certain clues from her weekly responses/essays seemed to click with the little bit we knew about Cheryl. And when I read Cheryl's excellent essay "Munro Country"—now one of my favorite essays—I was completely convinced.

Victoria and I sometimes teased about knowing her identity when we wrote about Sugar on Facebook. A friend from grad school and Victoria had a brief back-and-forth about it, and Cheryl wrote them a private message and kinda-sorta spilled the beans. Unofficially, you know.

Some of her readers wondered if knowing Sugar's identity would spoil the magic. Once I knew for sure that Sugar was actually this other "real" writer that I respected 100% in every possible way — well, let's just say I've never been a regular reader of advice columns until now.

Her memoir Wild is terrific. I read an early review copy in a couple of days, but I plan to order the book, as well.

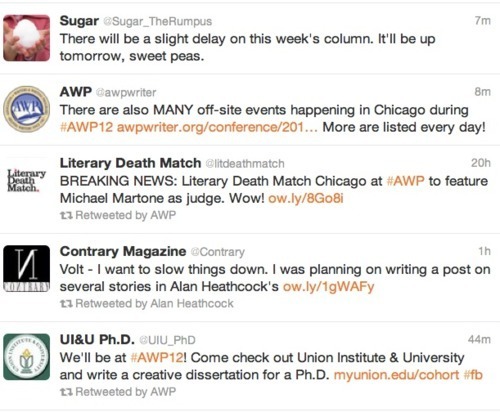

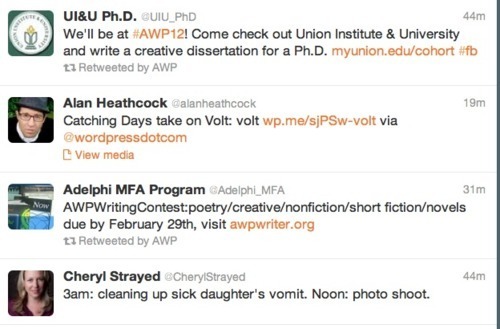

Recently, I couldn't help but notice a few compelling juxtapositions in my Twitter feed. Sugar and Cheryl seemed to post within minutes of each other quite often. I screen-captured a few of them for posterity. Click to enlarge the images so you can read the tweets.

February 1, 2012

What Do You Want from a Bookstore?

A simple post this week, one that relies on your input. I sure hope you'll leave a comment below. Repost and retweet at will.

With all of the talk about Amazon destroying the world, Barnes & Noble's "last stand," and the Borders collapse, many readers have gone searching for independent bookstores to support. If you were to start your own bookstore, as author Ann Patchett recently did, what qualities would you deem essential to its success? Or, even if you just view this hypothetical from a customer's perspective, what do you want from a bookstore?

January 27, 2012

The Grumpy Man's Guide to Etiquette for Writers and Editors

1. It's fine to tout your wares, but throw some love to people who aren't you, too. When you link to your recent publication, book, or blog post several times/days in a row, I want to punch you in the neck. This isn't Blue's Clues, Narcissus.

2. Stop using the word slush. Stop saying slush pile. Especially if you're talking about submissions sent online. There is no pile. You're just being an asshole.

3. Some agents and presses only read queries sent by mail. Some are open to e-mail queries. Nobody wants a query sent through Facebook. What the hell is wrong with you? Why "friend" an editor or agent just so you can bug them about your manuscript? RIght, because insincerity always works.

4. You know what? There is no reason for agents, et. al., to not accept queries by e-mail. You sell eBook rights? You can handle Gmail. Put that Ivy League education to work.

5. I like you. I like your book. You like my book, too. Aren't we dandy? But if you send me another event invitation to a reading that isn't within driving distance, I will cut you.

6. If an editor specifically asks you to submit work, whether it's a solicitation or part of an encouraging rejection letter, send only your best work.

7. Magazines and journals should not charge writers to submit. A contest entry is different. A writing contest is a lottery for people who look down on people who play the lottery.

8. If your submission is accepted elsewhere, withdraw it from all other journals currently considering it. If a journal uses an online submissions manager, this is exceedingly easy. Don't write the editor asking them to withdraw it. If the editor writes you back and kindly and gently explain how to use the online manager to withdraw a submission, don't respond with, "Indeed, the world gets more and more social." Whatever that means, weirdo.

9. Nobody cares how many words you wrote today. "Wooooooo, I wrote 928 words!" That's what you're supposed to do, knucklehead. Nobody in the office is running around saying, "Man, I sent the shit outta that fax! Did you see that? Boo-yah."

January 23, 2012

"Books have the same enemies as people: fire, humidity, animals, weather, and their own content."

- Paul Valery (1871-1945)

Andrew Scott's Blog

- Andrew Scott's profile

- 9 followers