Michael Shermer's Blog, page 17

September 13, 2011

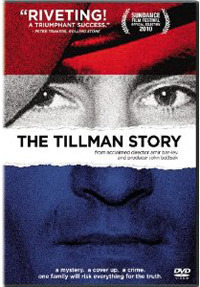

Pat Tillman's Atheism

In the 2010 documentary film, The Tillman Story, the story of Pat Tillman and his tragic death at the hands of "friendly fire" is retold. Tillman was the NFL star who gave it all up to join the military cause in Afghanistan after being inspired by 9/11 to do something for his country. He did not do it for the glory or publicity, and gave up a lucrative football career for what he perceived to be a worthy cause. After his death the U.S. government implemented a publicity campaign to use Tillman's death as a tool to promote the war as a cause so worthy that even a highly-paid NFL star believed it to be worth the sacrifice. What the government failed to mention is that Tillman was killed at the hands of his fellow soldiers during a "fog of war" incident in a steep and narrow slot canyon in which there was much confusion about where enemy fire was originating. It's a very disturbing film to watch—infuriating in fact—and Jon Krakauer's book, Where Men Win Glory, presents the story in excruciating detail in a compelling narrative.

Pat Tillman was an atheist. At his funeral his younger brother Richard got up to speak, visibly upset, noticeably inebriated, and with beer in hand proceeded to thank everyone for their warm sentiments, but upbraided those like Maria Shriver and Senator John McCain who made religious overtones in their sentiments, noting about his brother Pat: "He's not with God, he's fucking dead. He's not religious. Thanks for your thoughts, but he's fucking dead."

Later in the film there is a radio interview presented with Colonel Ralph Kauzlarich, who was the Regimental Executive Officer at Forward Operating Base Salerno on Khost, Afghanistan, under which Tillman was serving at the time of his death, and who led the military investigation into Pat's death. I found the following exchange to be among the most disturbing things in the entire film that was missed by most reviewers, starting in reference to the grieving Tillman family who were at the time vigorously pursuing an investigation into Pat's death and the government cover up of it:

Kauzlarich: "These people are having a hard time letting it go. It may be because of their religious beliefs. I don't know how an atheist thinks, but I can only imagine that that would be pretty tough. If you're an atheist and you don't believe in anything, if you die what is there to go to? Nothing. You're worm dirt. It's pretty hard to get your head around that."

Host: "So you suspect that's probably the reason this thing [the family's persistence in getting to the bottom of Pat's death] is running on."

Kauzlarich: "I think so. There's not a whole lot of trust in the system or faith in the system."

So…if you're an atheist it means that you're not going to buy into the belief that death—even a tragic, unnecessary, and friendly-fire death—will somehow be made acceptable by the belief that all will be made right in heaven where all the good Conservative Christian soldiers will meet up once again. This is very disturbing. What this knucklehead nincompoop is saying is that if the Tillman family were good Christians they would have gone along with the patriotic platitudes of the military in assuaging everyone's grief by pretending that it was all done in the name of god and country. But since the Tillmans are atheists it means that they actually want truth and justice now! How inconvenient. How pathetic. And this is yet another point against religious belief: it leads you to blur your focus on the here-and-now and let slip your grip on reality, and allow yourself to be manipulated by those who have neither the conscience nor the courage to stand up for what is right and true.

September 6, 2011

The Way of the Mister, Vol. 1: Reparative Therapy

This is the first of what will be a series of videos on differing topics. "The Way of the Mister" videos continue the ethos of the Mr. Deity worldview, but branch out in ways that would not work within the the Deity cosmography or with the Deity characters. It is the cast's desire to do more videos like this, and the ideas are pouring out of Brian Dalton. But many of them require bigger budgets than they currently have and they're hoping to rectify that with a non-profit organization which will focus on this broader mission — to educate with humor and satire.

Michael Shermer has a short cameo in this episode.

September 1, 2011

What is Pseudoscience?

is problematic

CLIMATE DENIERS ARE ACCUSED OF PRACTICING PSEUDOSCIENCE, as are intelligent design creationists, astrologers, UFOlogists, parapsychologists, practitioners of alternative medicine, and often anyone who strays far from the scientific mainstream. The boundary problem between science and pseudoscience, in fact, is notoriously fraught with definitional disagreements because the categories are too broad and fuzzy on the edges, and the term "pseudoscience" is subject to adjectival abuse against any claim one happens to dislike for any reason. In his 2010 book Nonsense on Stilts (University of Chicago Press), philosopher of science Massimo Pigliucci concedes that there is "no litmus test," because "the boundaries separating science, nonscience, and pseudoscience are much fuzzier and more permeable than Popper (or, for that matter, most scientists) would have us believe."

It was Karl Popper who first identified what he called "the demarcation problem" of finding a criterion to distinguish between empirical science, such as the successful 1919 test of Einstein's general theory of relativity, and pseudoscience, such as Freud's theories, whose adherents sought only confirming evidence while ignoring disconfirming cases. Einstein's theory might have been falsified had solar-eclipse data not shown the requisite deflection of starlight bent by the sun's gravitational field. Freud's theories, however, could never be disproved, because there was no testable hypothesis open to refutability. Thus, Popper famously declared "falsifiability" as the ultimate criterion of demarcation.

The problem is that many sciences are nonfalsifiable, such as string theory, the neuroscience surrounding consciousness, grand economic models and the extraterrestrial hypothesis. On the last, short of searching every planet around every star in every galaxy in the cosmos, can we ever say with certainty that E.T.s do not exist?

Princeton University historian of science Michael D. Gordin adds in his forthcoming book The Pseudoscience Wars (University of Chicago Press, 2012), "No one in the history of the world has ever self-identified as a pseudoscientist. There is no person who wakes up in the morning and thinks to himself, 'I'll just head into my pseudolaboratory and perform some pseudoexperiments to try to confirm my pseudotheories with pseudofacts.'" As Gordin documents with detailed examples, "individual scientists (as distinct from the monolithic 'scientific community') designate a doctrine a 'pseudoscience' only when they perceive themselves to be threatened—not necessarily by the new ideas themselves, but by what those ideas represent about the authority of science, science's access to resources, or some other broader social trend. If one is not threatened, there is no need to lash out at the perceived pseudoscience; instead, one continues with one's work and happily ignores the cranks."

I call creationism "pseudoscience" not because its proponents are doing bad science—they are not doing science at all—but because they threaten science education in America, they breach the wall separating church and state, and they confuse the public about the nature of evolutionary theory and how science is conducted.

Here, perhaps, is a practical criterion for resolving the demarcation problem: the conduct of scientists as reflected in the pragmatic usefulness of an idea. That is, does the revolutionary new idea generate any interest on the part of working scientists for adoption in their research programs, produce any new lines of research, lead to any new discoveries, or influence any existing hypotheses, models, paradigms or world views? If not, chances are it is pseudoscience.

We can demarcate science from pseudoscience less by what science is and more by what scientists do. Science is a set of methods aimed at testing hypotheses and building theories. If a community of scientists actively adopts a new idea and if that idea then spreads through the field and is incorporated into research that produces useful knowledge reflected in presentations, publications, and especially new lines of inquiry and research, chances are it is science.

This demarcation criterion of usefulness has the advantage of being bottom up instead of top down, egalitarian instead of elitist, nondiscriminatory instead of prejudicial. Let science consumers in the marketplace of ideas determine what constitutes good science, starting with the scientists themselves and filtering through science editors, educators and readers. As for potential consumers of pseudoscience, that's what skeptics are for, but as always, caveat emptor.

August 30, 2011

Skepticism 101: A Call for Course Syllabuses from Those Teaching Skeptical Courses

TO ALL TEACHERS AND PROFESSORS who are teaching courses in skepticism, critical thinking, science and pseudoscience, science and the paranormal, science studies, history or philosophy of science, the psychology of paranormal beliefs, religious studies, and the like…

Please send us your course syllabuses, reading lists, video/YouTube links, classroom demonstration ideas, student projects and experiments, research project ideas, and the like to my graduate student Anondah Saide. I want to add them to my own course syllabus on Skepticism 101, and create an online Skeptical Studies Program at Skeptic.com for teachers and professors everywhere to go to in a creative commons/open source system so that we can build a new academic field going forward with skepticism into academia.

I know that such courses are being taught around the world because for the past two decades of publishing Skeptic magazine and writing skeptical books, I receive a lot of mail from teachers and professors seeking permission to use our materials.

What I would like to do is to create academic departments of Skeptical Studies, as the next step in the skeptical movement. (See, for example, Phil Zuckerman's program of Secular Studies he is implementing this year at Pitzer College in Claremont, where I teach a graduate course in the spring. We have magazines and journals, trade books and conferences. The next step is a more organized penetration into academia via courses, textbooks, departments, and the like. I want to create a clearing house, an open-source site for people to access materials that will be made available to create your own course in Skeptical Studies, such as Skepticism 101: syllabuses, books, articles, assignments, videos, demonstrations, experiments, research projects, and the like. I am envisioning something along the lines of how psychology became an academic field a century ago.

To start the process off I share with you my own course syllabus for Skepticism 101, which I am teaching this semester starting this week at Chapman University on Tuesdays from 4–7pm with 36 freshman, the future of the skeptical movement!

Download Shermer's Course Syllabus for Skepticism 101

August 22, 2011

34 Answers About Belief

In this YouTube video series for Mahalo.com, Michael Shermer answers 34 questions about belief and rationality. Mahalo.com is an education-based website revolving around original video content filmed in Santa Monica, CA. The site aims to help people learn how to do anything and everything.

Among the 34 videos, you'll find:

Why do we need a belief in God?

Why did you write The Believing Brain

Do you think children should be taught to be more skeptical?

Is there a psychological difference between open- and close-minded people?

What are some of the strangest beliefs you've ever encountered?

Is it possible to retrain our brains and belief systems?

VIEW the entire playlist on YouTube.

Below is the second of the 34 videos. The entire series (total running time: 50 min. 32 seconds) can be viewed as a playlist on YouTube.

August 16, 2011

Folk-Wisdom Medicine versus Science-Based Medicine

This article first appeared as an alternative medicine opinion editorial for the American Medical Associations's Virtual Mentor Journal, Volume 13, Number 6: 389–393, June 2011.

For many years now there has been considerable debate between so-called complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and mainstream science-based medicine. In reality there is no debate because there is only science-based medicine and everything else that has yet to be tested. Most of CAM falls into this latter category. This does not automatically mean that all CAM claims are false; only that most of them have yet to be tested through the rigorous methods of science, which begins with the null hypothesis that holds that the hypothesis under investigation is not true (null) until proven otherwise. A null hypothesis states that X does not cause Y. If you think X does cause Y then the burden of proof is on you to provide convincing experimental data to reject the null hypothesis.

The statistical standards of proof needed to reject the null hypothesis are substantial. Ideally, in a controlled experiment, we would like to be at least 95–99 percent confident that the results were not due to chance before we offer our provisional assent that the effect may be real. Everyone is familiar with the process already through news stories about the FDA approving a new drug after extensive clinical trials. The trials to which they refer involve sophisticated methods to test the claim that Drug X (say a statin drug) improves outcomes in Disease Y (say cholesterol-related atherosclerosis). The null hypothesis states that statins do not lower cholesterol and thus have no effect on atherosclerosis. Rejecting the null hypothesis means that there was a statistically significant difference between the experimental group receiving the statins and the control group that did not.

In most cases CAM hypotheses do not pass these simple criteria. They have either failed to reject the null hypothesis, or they haven't even been rigorously tested to know whether or not they could reject the null hypothesis.

What, then, is the pull of CAM for so many people? According to a 2002 survey of U.S. adults conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine: 74.6% had used some form of complementary and alternative medicine, 14.8% "sought care from a licensed or certified" practitioner, suggesting that "most individuals who use CAM self-prescribe and/or self- medicate,"1 and that the most common CAM therapies used were prayer (45.2%), herbalism (18.9%), breathing methods (11.6%), meditation (7.6%), chiropractic (7.5%), yoga (5.1%), body work (5.0%), diet-based therapy (3.5%), progressive relaxation (3.0%), mega-vitamin therapy (2.8%), and visualization (2.1%).2

A 2004 survey of 1,400 U.S. hospitals found that over 25% offered such alternative and complementary therapies as acupuncture, homeopathy, and massage therapy. According to researchers Sita Ananth of Health Forum, an affiliate of the American Hospital Association, and William Martin, PsyD, of the College of Commerce at DePaul University in Chicago, in a news release: "More and more, patients are requesting care beyond what most consider to be traditional health services. And hospitals are responding to the needs of the communities they serve by offering these therapies."3

Herein lies one answer to understanding why CAM sells. There is a market demand for it. Why? One possibility is that people are turning to alternative medicine because their needs are not being met by traditional medicine. As the late medical historian Roy Porter was fond of pointing out, before the 20th century this certainly was the case.4 Medical historians, in fact, are in agreement that until well into the 20th century it was safer not to go to a doctor, thus leading to the success of such nonsense as homeopathy—a totally worthless nostrum that did no harm, thus allowing the body to heal itself. Since humans are pattern-seeking animals we credit as the vector of healing whatever it was we did just before getting well. This is also known as superstition, or magical thinking.

Another explanation may be found in examining what CAMers are offering that mainstream physicians are not: TLC. By this I do not just mean a hand squeeze or a hug, but an open and honest relationship with patients and their families that provides a realistic assessment of the medical condition and prospects. People are going alternative because in too many instances physicians have become highly skilled technicians—cogs in the cold machinery and massive bureaucracy of modern HMO medicine.

I witnessed the effect directly over the course of a decade during my mother's recurring and malignant meningioma brain tumors. She finally succumbed, but in the process I gained a deeper understanding of why people turn to alternative medicine. Don't get me wrong—my mother's doctors were brilliant, her care the very best available, and we have no regrets about what might have been. And that's the point. Even under such ideal conditions I found the whole experience frustrating and unfulfilling: it was nearly impossible to get honest and accurate information about my mom's condition; neither my father nor I could get doctors to return our calls; misinformation and (usually) no information was the norm; and despite my best efforts, the relationship with her physicians (with one exception—her oncologist whom I befriended), could not have been more detached.

I found it rather telling, for example, that when I identified myself as "Dr. Shermer" I got faster results at the hospital than when I was merely "Mr. Shermer" (a lie of omission, not commission, since I do have a Ph.D.), but I still found it difficult to get calls returned. Even worse, when my mom's oncologist (one of the country's best-known and well-respected in his field) called her surgeons, he too heard too many dial tones. If physicians show such a remarkable lack of professional courtesy with their own colleagues, what are the rest of us to expect?

More than anything patients want information. They want to know what is really going on. They don't want jargon. They don't want false hope or unnecessary pessimism. Studies show that patients do better when they know in detail all the steps they will have to take in their recovery process—probably because it allows them to anticipate, plan, and pace themselves. Knowledge is power, and physicians are modern-day shamans. Patients want the power that knowledge brings, and that empowerment cannot be given in the 8.5 minutes the average doctor spends per patient per visit. Patients want a relationship with their primary caretaker that allows them to ask the important questions and expect honest answers.

Physicians tend to have monologues when they should be having dialogues. The reasoning process of diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment goes on inside their heads, and what comes out is a glossed telegram of truncated lingo. The physician-patient connection is a one-way street, an authority-flunky relationship top heavy in arrogance and off-putting to anyone with a modicum of self-esteem and social awareness. If I could reduce all this into a single request, it is this: Talk to patients as if they are thoughtful, intelligent people capable of understanding and deeply curious about their condition.

So…we should turn to CAM then, right? Wrong. An even deeper problem is that CAMers lack much medical knowledge and (especially) scientific reasoning, making them dangerous. The 2002 study referenced above found that 54.9% used CAM in conjunction with conventional medicine but did not always tell their primary care physician, thus leading to possibly deadly mixtures of drugs and herbs.1 It is not a matter of everything to gain and nothing to lose by going CAM (even if your doc offers no hope), because quack medicines cost money, cause harm, and, most importantly, take away valuable time that could and should be spent with loved ones in this already too-short of a stay we have with each other.

Besides TLC, the cognitive pull of CAM is anecdotal thinking. Since humans are pattern-seeking animals, we credit whatever we did just before getting well as the vector of healing. If A appears to be connected to B, we assume that it is unless proven otherwise. This is the very antithesis of the science-based system of the null hypothesis. The recent medical controversy over whether vaccinations cause autism reveals the power of anecdotal thinking. On the one side are scientists who have been unable to find any causal link between the symptoms of autism and the vaccine preservative thimerosal, which breaks down into ethylmercury, the culprit du jour for autism's cause. On the other side are parents who noticed that shortly after having their children vaccinated autistic symptoms began to appear. These anecdotal associations are so powerful that it causes people to ignore contrary evidence: ethylmercury is expelled from the body quickly (unlike its chemical cousin methylmercury) and therefore cannot accumulate in the brain long enough to cause damage, and rates of autism diagnoses did not decline in children born after thimerosal was removed from vaccines.

The anecdotal thinking upon which CAMers rely—even if unconsciously and with the best of intentions—can be particularly dangerous in the hands of those whose intentions are less than ethical. Thus it is that any medical huckster promising that A will cure B has only to advertise a handful of successful anecdotes in the form of testimonials, and the human brain will do the rest. By way of example from the annals of medical quackery, witness the case of John R. Brinkley, one of the greatest medical quacks of the first half of the twentieth century, and his nemesis Morris Fishbein, the quackbusting editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association. Their decades-long struggle that criss-crossed the American heartland throughout the 1920s and 1930s, represents this tension between folk and scientific medicine, well summarized in Pope Brock's 2008 book Charlatan: America's Most Dangerous Huckster, the Man Who Pursued Him, and the Age of Flimflam.5

What Brinkley was selling was what all men want—sexual vitality—and he developed a surgical technique that offered the type of firm results that his male clientele so desperately sought: goat testis sewn right into the patient's scrotum, which he likened to "embedding a marble in an apple." Come one, come all. And they did, to the tune of $750 per surgery, advertised widely in newspapers (an AMA study revealed that over half of all newspaper advertising at the time was for patent medicines) and the new fangled technology—radio—which Brinkley took to like an evangelist to television. The ads featured testimonials from happy men who proclaimed their restored manhood, and these anecdotes made Brinkley a rich man as it drove customers to his practice. But as his business grew he got careless, performing operations both before and after happy hour, and fobbing off work to assistants whose medical credentials were even shadier than his own (Brinkley graduated from the unaccredited and improbably named Eclectic Medical University of Kansas City). The result was dozens of dead patients.5

This got the attention of the ambitious Morris Fishbein, whose career coincided with the rise of the AMA's attempt to rein in flimflammery through accrediting medical colleges and licensing practitioners. Fishbein made his public mark in 1923 when the Chicago Daily News sent him to investigate the "Hot Girl of Escanaba" (Michigan), a woman who suffered from a temperature of 115 degrees for two weeks. Fishbein exposed her as a "hysterical malingerer" when he discovered that a flesh colored hot water bottle was employed to elevate rectal thermometer readings. For the next two decades Fishbein pursued the country's "most daring and dangerous" swindler, as he called Brinkley, until he finally brought him down in a decisive courtroom confrontation.5

Fishbein's promotion of science-based medicine was heroic in his day, but medical flapdoodle flourishes today on the Internet so every medical association and journal needs a quackbusting Fishbein on its staff, for without such eternal vigilance folk medicine will trump scientific medicine in the minds of patients. And thus it is that skepticism should be our default rule of thumb when it comes to CAM claims.

References

Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. "Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002." Adv Data. 2004;(343):6. http://nccam.nih.gov/news/camstats/2002/report.pdf. Accessed May 17, 2011.

Barnes, Powell-Griner, McFann, Nahin, 12.

Ananth S. Health Forum 2005 Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals [news release]. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; July 19, 2006. And: www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006/07/20/health/webmd/main1823747.shtml

Porter R. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity . New York: W.W. Norton; 1999.

Brock P. Charlatan: America's Most Dangerous Huckster, the Man Who Pursued Him, and the Age of Flimflam . New York: Crown Books; 2008.

August 3, 2011

Mr. Deity and the Believing Brain

Mr. Deity seeks help from Michael Shermer to make his creatures more gullible.

August 1, 2011

Globaloney

FAST-FORWARD TO THE YEAR 2100. Computers, writes physicist and futurist Michio Kaku in Physics of the Future (Doubleday, 2011), will have humanlike intelligence, the Internet will be accessible via contact lenses, nanobots will eliminate cancers, space tourism will be cheap and popular, and we'll be colonizing Mars. We will be a planetary civilization capable of consuming the 1017 watts of solar energy falling on Earth to meet our energy needs, with the Internet as a worldwide telephone system; English and Chinese as the contenders for a planetary language; a unified culture of common foods, fashions and films; and a truly global economy with many more international trading blocs such as we see today in the European Union and NAFTA.

Kaku's vision of how the exchange of science, technology and ideas among all peoples will create a global civilization with greatly weakened nation-states and almost no war is epic in its scope and heroic in its inspiration. Many have felt similar hope for a united, peaceful future through globalization. Indeed, I evoked a similar image in my book The Mind of the Market (Holt, 2009), and I was inspired in part by Thomas Friedman's wildly popular The World Is Flat (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005), in which he argues for "a global, Web-enabled playing field that allows for multiple forms of collaboration on research and work in real time, without regard to geography, distance or, in the near future, even language."

The problem for Kaku, Friedman, me and other globalization proponents (and even opponents) is that such a future may be unattainable because of our evolved tribal natures. In fact, this is all a bunch of "globaloney," says Pankaj Ghemawat, professor of strategic management and Anselmo Rubiralta Chair of Global Strategy at IESE Business School at the University of Navarra in Barcelona, in his new book World 3.0: Global Prosperity and How to Achieve It (Harvard Business Review Press, 2011). According to Ghemawat, only 10 to 25 percent of economic activity is international (and most of that is regional rather than global). Consider the following percentages (of the total in each category): international mail: 1; international telephone calling minutes: less than 2; international Internet tra!c: 17 to 18; foreign-owned patents: 15; exports as a percentage of GDP: 26; stock-market equity owned by foreign investors: 20; first-generation immigrants: 3. As Ghemawat starkly notes, 90 percent of the world's people will never leave their birth country. Some flattened globe.

The problem, Ghemawat says, is that globalization theories fail to account for the very real distance factors (geographic and cultural). He crunches these factors into a distance coefficient akin to Newton's law of gravitation. For example, he computes, "a 1 percent increase in the geographic distance between two locations leads to about a 1 percent decrease in trade between them," a distance sensitivity of –1. Or, he calculates, "U.S. trade with Chile is only 6 percent of what it would be if Chile were as close to the United States as Canada." Likewise, "two countries with a common language trade 42 percent more on average than a similar pair of countries that lack that link. Countries sharing membership in a trade bloc (e.g., NAFTA) trade 47 percent more than otherwise similar countries that lack such shared membership. A common currency (like the euro) increases trade by 114 percent."

That analysis actually sounds encouraging to me if we use Kaku's projected time frame of 2100. But Ghemawat reminds us of our deeply ingrained tendencies to want to interact with our kin and kind and to retain our local customs and culture, which may forever balkanize any globalized scheme. Even as the E.U. expands, for instance, an average of "Eurobarometer" surveys of residents of 16 E.U. countries between 1970 and 1995 made in 2004 by researchers at the Center for Economic and Policy Research found that 48 percent trust their fellow nationals "a lot," 22 percent trust citizens of other E.U.-16 countries a lot and only 12 percent trust people in certain other countries a lot. Human nature's constitution dictates the constitution of human society. In this sense, the world we make very much depends on the world we inherit.

July 26, 2011

The Believing Brain

of belief-dependent realism

WAS PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA BORN IN HAWAII? I find the question so absurd, not to mention possibly racist in its motivation, that when I am confronted with "birthers" who believe otherwise, I find it diffcult to even focus on their arguments about the difference between a birth certificate and a certificate of live birth. The reason is because once I formed an opinion on the subject, it became a belief, subject to a host of cognitive biases to ensure its verisimilitude. Am I being irrational? Possibly. In fact, this is how most belief systems work for most of us most of the time.

We form our beliefs for a variety of subjective, emotional and psychological reasons in the context of environments created by family, friends, colleagues, culture and society at large. After forming our beliefs, we then defend, justify and rationalize them with a host of intellectual reasons, cogent arguments and rational explanations. Beliefs come first; explanations for beliefs follow. In my new book The Believing Brain (Holt, 2011), I call this process, wherein our perceptions about reality are dependent on the beliefs that we hold about it, belief-dependent realism. Reality exists independent of human minds, but our understanding of it depends on the beliefs we hold at any given time.

I patterned belief-dependent realism after model-dependent realism, presented by physicists Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow in their book The Grand Design (Bantam Books, 2011). There they argue that because no one model is adequate to explain reality, "one cannot be said to be more real than the other." When these models are coupled to theories, they form entire worldviews.

Once we form beliefs and make commitments to them, we maintain and reinforce them through a number of powerful cognitive biases that distort our percepts to fit belief concepts. Among them are:

ANCHORING BIAS: relying too heavily on one reference anchor or piece of information when making decisions.

AUTHORITY BIAS: valuing the opinions of an authority, especially in the evaluation of something we know little about.

BELIEF BIAS: evaluating the strength of an argument based on the believability of its conclusion.

CONFIRMATION BIAS: seeking and finding confirming evidence in support of already existing beliefs and ignoring or reinterpreting disconfirming evidence.

On top of all these biases, there is the in-group bias, in which we place more value on the beliefs of those whom we perceive to be fellow members of our group and less on the beliefs of those from different groups. This is a result of our evolved tribal brains that lead us not only to place such value judgment on beliefs but also to demonize and dismiss them as nonsense or evil, or both.

Belief-dependent realism is driven even deeper by a meta bias called the bias blind spot, or the tendency to recognize the power of cognitive biases in other people but to be blind to their influence on our own beliefs. Even scientists are not immune, subject to experimenter-expectation bias, or the tendency for observers to notice, select and publish data that agree with their expectations for the outcome of an experiment and to ignore, discard or disbelieve data that do not.

This dependency on belief and its host of psychological biases is why, in science, we have built-in self-correcting machinery. Strict double-blind controls are required, in which neither the subjects nor the experimenters know the conditions during data collection. Collaboration with colleagues is vital. Results are vetted at conferences and in peer-reviewed journals. Research is replicated in other laboratories. Disconfirming evidence and contradictory interpretations of data are included in the analysis. If you don't seek data and arguments against your theory, someone else will, usually with great glee and in a public forum. This is why skepticism is a sine qua non of science, the only escape we have from the belief-dependent realism trap created by our believing brains.

Flowers for Nim

When I was in a psychology graduate program in the late 1970s, the nature v. nurture debate was in full-throated either-or mode, with crudely conceived experiments and data sets marshaled to defend one side or the other, as if asking whether π or r2 is more important in calculating the area of a circle. (Thankfully this debate today has morphed into much more sophisticated research by behavioral geneticists and others to understand how nature and nurture interact, well summarized in Steven Pinker's The Blank Slate and Matt Ridley's Nature via Nurture.) In addition to the studies examining twins separated at birth and raised in separate environments, I recall that raising chimpanzees in a human environment and trying to teach them sign language garnered considerable media attention as pioneering research into understanding the nature of human (and primate) nature, along with language and cognition. These were heady times of bold experimentation, the most prominent being Project Nim, initiated and monitored by Columbia University psychologist Herbert Terrace. Terrace in particular wanted to test MIT linguist Noam Chomsky's then controversial theory that there is an inherited universal grammar that is the basis to language and unique to humans, by teaching our closest primate cousin American Sign Language (ASL). Terrace, however, did a turnabout, concluding that the signs Nim Chimpsky (a cheeky nod to Noam Chomsky) learned from his human companions and trainers amounted to little more than animal begging, more sophisticated perhaps than Skinner's rats and pigeons pressing bars and pecking keys, but in principle not so different from what dogs and cats do to beg for food, be let outside, etc.—a "Clever Hans" effect in primates. His 1979 book, Nim, outlines the project and his assessment of its results. There have been many evaluations and critiques since that time, most recently by Elizabeth Hess in her 2008 book, Nim Chimpsky: The Chimp Who Would Be Human (Bantam Books), which is the basis of the new documentary film, Project Nim, by James Marsh (whose previous film, Man on Wire, is portrays the tightrope walker Philippe Petit).

Project Nim is a dramatic and disturbing critique of Terrace's research and the treatment of Nim that also serves as something of an indictment of the entire enterprise of animal behavioral research. Having worked in an animal lab for two years training rats and pigeons in Skinner boxes, I was deeply moved by the perspective several decades have brought to what we were doing to animals back then in the name of science. There is, however, next to no science presented in this film, and perhaps that is the way it should be because how that data was collected was, by today's standard, so sloppy as to be virtually worthless, or at the very least morally questionable.

It is with some irony that Nim spent the remainder of his post-experimental life at the Black Beauty Ranch in Texas, because Project Nim is, on one level, presented from his perspective, through the eyes (often tearing up) and voices (often cracking) of his trainers and handlers. Nim was ripped from the arms of his mother at only a few weeks old. As he was the seventh of her children to be so seized she had to be tranquilized and grabbed quickly so that she did not accidentally smother her baby that she clutched to her chest in motherly love and protection, as she collapsed on the floor. Stop right there. Five minutes into the film and I'm already wondering what science tells us about the effects on a mother of having her seven children stolen from her arms.

Marsh's film shuttles between talking-head interviews with all the major players in the project (including Terrace himself) and original footage shot throughout the experiment. Nim began his childhood in an upper west side brownstone New York apartment surrounded by human siblings in the mildly dysfunctional LaFarge family spearheaded by Stephanie, who breast-fed Nim and, as he got older, allowed him to explore her nakedness even as he put himself between his adopted mother and her poet husband in an Oedipal scene right out of Freud. Just as Nim grew into his new family, surrounded by fun-loving human siblings and days filled with games and hugs, Terrace realized that scientists were not going to take him seriously because there was next to no science going on in this free-love home. (According to one of the trainers, there were no lab manuals, no diaries, no data sheets, no recordings of progress, and no one in the family even knew how to sign ASL!) So for a second time in his young life Nim was wrenched from his mother and placed into a more controlled environment in the form of a sprawling home owned by Columbia University. There a string of trainers carefully monitored Nim's progress in learning ASL, making daily trips to a lab at the university where Terrace could control all intervening variables in a manner not dissimilar to a Skinner box. There some halting progress was made, but Nim was clearly not enamored at being shuttled back and forth between the Disneylandesque environment of home and the sterile environment of the lab, and it is unclear whether his lack of significant progress was the result of cognitive shortcomings or simian protest.

In due time Nim grew into his teenage years, and as most testosterone-fueled male primates are wont to do, he became more assertive, then aggressive, then potentially dangerous in his evolved propensity to test his fellow primates for hierarchical status in the social pecking order. The problem is that adult chimpanzees are 5-10 times stronger than humans. In other words, Nim became a threat. As one of the trainers said while pointing to a scar on her arm that required 37 stitches: "You can't give human nurturing to an animal that could kill you." After several of these biting incidents that sent trainers and handlers to the hospital, including one woman who had part of her cheek ripped open, Terrace pulled the plug on the experiment and therewith shipped Nim back to the research lab in Oklahoma from whence he came. Tranquilized into unconsciousness, Nim went to sleep surrounded by loving human caretakers on a sprawling estate in New York and awoke in a grey-bar cold steel cage in Oklahoma.

Having never seen another member of his species Nim was understandably anxious and scared at the sight of grunting, hooting male chimps eager to let the youngster know his place in the pecking order. I imagined that it must have been something like being tossed into a maximum-security prison with muscle-bound, tattoo-hardened murderers and rapists looking at you like fresh meat to be pounded on. As a result, Nim slipped into a deep depression, losing weight and refusing to eat. A year later Terrace visited Nim, who greeted him eagerly and expressed himself in a manner that Terrace himself described as signaling to get him out of this hell hole. Instead, Terrace took off the next day for home and Nim slid back into a depression. Some time later he was sold to a pharmaceutical animal-testing laboratory managed by New York University where Hepatitis B vaccinations were tested on our nearest primate relatives. Footage of a tranquilized chimp being pulled out of and stuffed back into a steel-barred cage barely big enough to turn around was sickening to watch. The emotional impact of the visual imagery left me to imagine what Nim would have signed to Professor Terrace had his vocabulary developed into fully human with the necessary colorful language for emotional expression appropriate for the situation: "Screw you Herb Terrace, you traitorous back-stabbing, low-life scumbag. You took me from my mother and my species. You robbed me of my simian childhood. You gave me a new mother then took her away from me just as I grew attached. You used me and abused me in the name of bogus science to further your own career, and when I protested you sold me off like so much raw meat. How about we put you into this hell-hole environment, lock you up behind bars, feed you crappy food, and make you sleep in your own piss and shit and see how you like it?"

In reality, no chimp has such verbal language, but violent incidents between chimps and humans and research on chimpanzees in the wild enables us to imagine what Nim would have done to Terrace given the opportunity and awareness of his ultimate responsibility for Nim's fate: Nim would likely have torn off his face, ripped open his neck, eaten his genitals, and left him for dead in seconds. At least that is what this film evokes in emotional desire for revenge on Nim's behalf. To be fair, the trainers and handlers come across as caring, loving people who did the best they could under the circumstances, but they had little say in the long-term course of Nim's existence. Terrace, by contrast, who ran the show and called the shots, comes across as an almost psychopathic manipulator, an alpha male egotist who, in his own words on camera, spoke of Nim's suffering in cold clinical language, saw absolutely nothing scientifically objectionable to employing mostly young nubile graduate students, most of whom he bedded during the research project then dispensed with before moving on to the next conquest. I realize that this was the free-love 1970s in which professors and students often conducted research between the sheets, but even by those standards Terrace appears to be the very embodiment of moral turpitude.

Momentarily, Terrace partially redeemed himself in my eyes when he admitted that the data he collected changed his mind on the nature-nurture debate—since Nim did not even remotely approach the complexity of language or cognition of humans, Chomsky was probably right. What a rare treat to hear a scientist say, "I was wrong." But after thinking about it for a day I came to the conclusion that even this might have been nothing more than a way of reducing cognitive dissonance for how Nim's life turned out. If Nim is human like, then the subhuman treatment of him becomes criminal. But if Nim is little more than a rat or pigeon, merely begging for food and favors like a lowly dog, then shipping him off to a research lab to live out his life in a cold steel cage perhaps doesn't seem so deplorable. Sadly, there was no Shawshank redemption for Nim. But thanks to this film we can at least put flowers on his metaphorical grave.

Michael Shermer's Blog

- Michael Shermer's profile

- 1155 followers