Michael Shermer's Blog, page 21

November 16, 2010

Throwing Cold Water on a Hot Topic

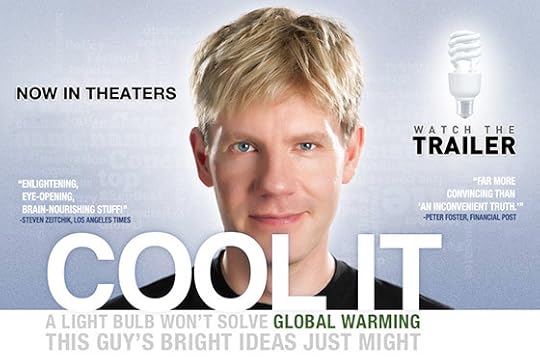

This post is a review of Cool It, a film by Bjorn Lomborg, directed by Ondi Timoner, produced by Roadside Attractions and 1019 Entertainment. Written by Terry Botwick, Sarah Gibson, and Bjorn Lomborg. Based on the book by Bjorn Lomborg. 88 minutes.

I FIRST MET BJORN LOMBORG IN 2001 upon the publication of his Cambridge University Press book, The Skeptical Environmentalist, which I found to be a refreshing perspective on what had been the doom-and-gloom, end-of-the-world scenarios that I had been hearing since I was an undergraduate in the early 1970s. Back then we were told that overpopulation would lead to worldwide hunger and starvation, that there would be massive oil depletion, precious mineral exhaustion, and rainforest extinction by the 1990s. These predictions failed utterly. I felt I had been lied to for decades by the environmentalist movement that seemed to me to be little more than a political movement that raised money by raising fears.

Lomborg's publicist thought that I might be interested in hosting him for the Skeptics Society's public science lecture series at the California Institute of Technology that I organize and host. I was, but given the highly debatable nature of many of Lomborg's claims I only agreed to host him if it could be a debate. Lomborg agreed at once to debate anyone, and this is where the trouble began. I could not find anyone to debate Lomborg. I contacted all of the top environmental organizations, and to a one they all refused to participate. "There is no debate," one told me. "We don't want to dignify that book," said another. I even called Paul Ehrlich, the author of the wildly popular bestselling book The Population Bomb — another apocalyptic prognostication that served as something of a catalyst in the 1970s for delimiting population growth — but he turned me down flat, warning me in no uncertain language that my reputation within the scientific community would be irreparably harmed if I went through with it. So of course I did because (A) truth is more important than reputation, and (B) no one threatens me and gets away with it. My own Senior Editor, Frank Miele, who is an expert on evolutionary biology and biodiversity (and is one of the fastest and most facile researchers I've ever known), challenged Lomborg on several of the chapters in his book, and we had a lively and successful debate.

My experience is symptomatic of deep problems that have long plagued the environmental movement, and for a time the political pollution of the science turned me into an environmental skeptic. That alone would be meaningless, given that I have only ever written one article on the subject (my June 2006 Scientific American column explaining that I flipped from climate skeptic to believer), but I believe that the environmental extremists had a similar effect on millions of others who remain skeptical in the teeth of what now appears to be reasonably solid evidence for anthropogenic global warming.

In fact, the documentary film Cool It, based on Lomborg's book of the same title that serves as the popular version of his more technical and scholarly first tome, opens with him stating unequivocally that global warming is real and human caused. Wait! I thought Lomborg was a climate denier? That is what his critics have accused him of being, in fact, which apparently is the charge delivered if one does not accept in full all the claims in Cool It's erstwhile anti-avatar, Al Gore's film An Inconvenient Truth. Here it might be useful to distinguish the two films by breaking down the subject matter into five questions:

Is the earth getting warmer?

Is the cause of global warming human activity?

How much warmer is it going to get?

What are the consequences of a warmer climate?

How much should we invest in altering the climate?

Al Gore's answers

Bjorn Lomborg's answers in Cool It

1

Yes

Yes

2

Yes

Yes

3

A lot

Probably a little, very unlikely a lot

4

Cataclysmic.

Debatable depending on how much warmer it will get, but very likely the consequences will be minor

5

Trillions of dollars, mostly top-down government programs to curtail oil and coal use and reduce greenhouse gases

Billions

Global warming is real and primarily human caused. With questions 3 and 4, however, estimates include error bars that grow wider the further out we run the models because complex systems like climate are notoriously difficult to predict. Lomborg (and myself) provisionally accept the estimate of the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that the mean global temperature by 2100 will increase by around 4–5 degrees Fahrenheit, and that sea levels will rise by about one foot, which Lomborg reminds us is about the same level that sea levels have risen since 1860, without any major (or for that matter minor) consequences. In other words, man-made global warming will be moderate, causing moderate changes.

Examining question 4 more closely, Lomborg computes that if global warming continues unchecked through the end of the century there will be 400,000 more heat-related deaths annually, but he then notes that there will be also be 1.8 million fewer cold-related deaths, for a net gain of 1.4 million lives. This is a typical calculation that Lomborg makes in what is essentially an economic triage for global warming — he is not saying that global warming is good or inconsequential, only that its consequences must be weighed in the balance against other problems. For example, Lomborg sites data from the World Wildlife Fund that at most we will lose 15 polar bears a year due to global warming, but what doesn't get reported is that 49 bears are shot each year. What would be more cost-effective to save polar bear lives — spend hundreds of billions of dollars to lower CO2 emissions and (maybe) lower the mean global temperature by a fraction of a degree, or limit hunting permits?

This leads to question 5 — the economics of global climate change — which Lomborg notes that if all countries had ratified the Kyoto Protocol and lived up to its standards (which most did not), according to the IPCC at best it would have postponed the 4.7°F average increase just five years from 2100 to 2105, at a cost of $180 billion a year! By comparison, although global warming may cause an increase of two million deaths due to hunger annually by 2100, the U.N. estimates that for $10 billion a year we could save 229 million people from hunger annually today.

Economics is about the efficient allocation of limited resources that have alternative uses. If you had, say, $50 billion a year to make the world a better place for more people, how would you spend it? Cool It traces Lomborg's attempt to answer this question through a group of scientists, economists, and world leaders whom he gathered in 2004 in Copenhagen to reach what he calls the "Copenhagen Consensus." These experts ranked reduction of CO2 emissions 16th out of 17 challenges. The top four were: controlling HIV/AIDS, micronutrients for fighting malnutrition, free trade to attenuate poverty, and battling malaria. A 2006 Copenhagen Consensus of U.N. ambassadors constructed a similar list, with communicable diseases, clean drinking water, and malnutrition at the top, and climate change at the bottom. A late 2008 meeting that included five Nobel Laureates recommended that President-elect Barack Obama allocate his promised $150 billion in subsidies for new technologies and $50 billion in foreign aid be allocated for research on malnutrition, immunization, and agricultural technologies. For a cool Kyoto $180 billion you can buy a lot of condoms, vitamin tablets, and mosquito nets and rescue hundreds of millions of people from disease, starvation, and impoverishment.

Cool It is an uplifting film, filled with solutions that any green technophile would love: solar, wind, wave, and geoengineering technologies take up a lion's share of the film. (And true climate skeptics will denounce Lomborg on this front as they do not believe that these alternatives can come close to replacing coal and oil as sources of energy.) To his credit, the unflappable Lomborg, with his boyish good looks and curiosity, includes in his own film harsh disparaging commentary by his long-time critic Stephen Schneider, the Stanford University climate scientist who passed away this past July. In a very classy touch, Cool It is dedicated to Schneider.

* * *

Note: If you are skeptical of Lomborg and his branch of environmental skepticism, read the Yale University economist William Nordhaus' technical book A Question of Balance (Yale University Press, 2008). Nordhaus computes the costs-benefits of various recommendations for changing the climate by either 2105 or 2205, primarily focused on the cost of curbing carbon emissions. Economists like to compute future profits and losses based on investments made today, adjusting for the value of a future dollar at an average interest rate of four percent. If we spent a trillion dollars today (the equivalent of the recent bailout or the Iraq war), how much climate change would it buy us in a century at four percent interest? Nordhaus's calculations are compared to doing nothing, where a plus value is better and a minus value worse than doing nothing. Kyoto with the U.S. is plus one and without the U.S. zero, for example, and a gradually increasing global carbon tax is a plus three. That is, a $1 trillion cost today buys us $3 trillion of benefits in a century. Al Gore's proposals, by contrast, score a minus 21, where $1 trillion invested today in Gore's plans would net us a loss of $21 trillion in 2105. Add to these calculations the numerous other crises we face, such as the housing calamity, the financial meltdown, the coming pressures of funding Social Security and Medicare, not to mention financing two wars, a failing public education system, and so forth, and suddenly global climate change is put into perspective.

November 9, 2010

What Do You Believe In?

As a skeptic and atheist I am often asked, "What do you believe in?" The ending preposition implies something more than what factual claims are to be believed, such as evolution, quantum physics, or the big bang. What is suggested by the question is what values does one believe in or hold to, especially without belief in God and religion. Here is my answer.

I believe in the Principle of Freedom: All people are free to think, believe, and act as they choose, so long as they do not infringe on the equal freedom of others.

I believe in civil liberties, civil rights, and the freedoms guaranteed in the United States Constitution, including and especially freedom of speech, freedom of association, freedom to assemble peacefully, freedom to petition grievances, freedom to worship (or not), freedom of the press, freedom of reproductive choice, freedom to bear arms, etc.

I believe in the sanctity of private property, the rule of law, and equal treatment under the law.

I believe in free will, free choice, moral culpability, and personal responsibility.

I believe in truth seeking and truth telling.

I believe in trust and trustworthiness.

I believe in fairness and reciprocity.

I believe in love, marriage, and fidelity.

I believe in family, friendship, and community.

I believe in honor, loyalty, and commitment to family, friends, and community members.

I believe in forgiveness when it is genuinely asked for or offered.

I believe in kindness, generosity, and charity, especially voluntary aid to others in need.

I believe in science as the best method ever devised for understanding how the world works.

I believe in reason and logic and rationality as cognitive tools for answering questions, solving problems, and devising solutions to life's many problems and quandaries.

I believe in technological growth, cultural advancement, and moral progress.

I believe in the almost illimitable capacity of human creativity and inventiveness for our species to flourish into the far future on this planet and others.

Ad astra per aspera!

So, if you are ever asked by a believer what you believe in, offer your own list along these lines of values that you honor, and then ask, "Why, what do you believe in? Do you not honor these values?"

The impetus for essay, which I penned on a plane to Los Angeles on October 15, 2010, was that I was asked this very question the night before during the Q&A after a talk I delivered before a sizable audience at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, sponsored by CASH (Campus Atheists, Skeptics, and Humanists), supported by several other Minnesota atheist and humanist groups, and attended as well by many believers. The woman who made the inquiry explained that as an atheist she is often asked this question in a tone implying that atheists cannot or do not believe in anything.

Nothing could be further from the truth, of course, but such is the delimiting effect of religious belief and the myth that without God anything goes. Quite the contrary. Without God, values matter more here and now than they ever could in any projected afterlife proscenium where the moral play is finally enacted.

P.S. The final line above translates as: To the stars with difficulty. The phrase originated with the Roman poet Seneca the Younger and was made famous on a plaque honoring the Apollo 1 astronauts who perished in a fire on the launch pad at Cape Canaveral.

November 7, 2010

The Skeptic's Skeptic

SCIENCE VALUES DATA and statistics and champions the virtues of evidence and experimentation. Those of us "viewing the world with a rational eye" (as the new descriptor for this column reads) also have another, underutilized tool at our disposal: rapier logic like that of Christopher Hitchens, a practiced logician trained in rhetoric. Hitchens—who is "leaving the party a bit earlier than I'd like" because of esophageal cancer, as he lamented to Charlie Rose in a recent PBS interview—has something deeply important to o!er on how to think about unscientific claims. Although he has no formal training in science, I would pit Hitchens against any of the purveyors of pseudoscientific clap trap because of his unique and enviable skill at peeling back the layers of an argument and cutting to its core.

We would all do well to observe and emulate his power to detect and dissect baloney through pure thought. To wit, after watching a quack medicine man fleecing India's poor one Sunday afternoon, the belletrist scowled in a 2003 Slate column, "What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence." The observation is worthy of elevation to a dictum.

Of course, as scientists we prefer to tether evidence, when it is available, to logical analysis in support of a claim or to pro!er counterevidence that disputes a claim. A radiant example of Hitchens's insightful thinking, coupled to the effective employment of counterevidence, is his reaction to an episode of the television series Planet Earth. As he watched, he had a revelation of creationism's profound flaws. The episode was on life underground, during which Hitchens noticed that the blind salamander had "eyes" that "were denoted only by little concavities or indentations," as he recounted in a 2008 Slate commentary. "Even as I was grasping the implications of this, the fine voice of Sir David Attenborough was telling me how many millions of years it had taken for these denizens of the underworld to lose the eyes they had once possessed."

"What can be asserted without evidence

can also be dismissed

without evidence."

—Christopher Hitchens

Creationists make a big deal about the eye, insisting that the gradual stepwise process of natural selection could not have sculpted such a complex instrument because of "irreducible complexity," meaning that the removal of any part would render it useless. Even Charles Darwin fretted about the eye in On the Origin of Species: "To suppose that the eye, with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest possible degree."

If God created the eye, then how do creationists explain the blind salamander? "The most they can do is to intone that 'the Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away,'" Hitchens mused. "Whereas the likelihood that the postocular blindness of underground salamanders is another aspect of evolution by natural selection seems, when you think about it at all, so overwhelmingly probable as to constitute a near certainty." To confirm his instincts, Hitchens queried evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, who agreed: "Why on earth would God create a salamander with vestiges of eyes? If he wanted to create blind salamanders, why not just create blind salamanders? Why give them dummy eyes that don't work and that look as though they were inherited from sighted ancestors?"

Hitchens's point is even deeper, however, when he applies the counterfactual argument of regression to the cosmos itself, noting that "there is a dialectical usefulness to considering the conventional arguments in reverse, as it were. For example, to the old theistic question, 'Why is there something rather than nothing?' we can now counterpose the findings of Professor Lawrence Krauss and others, about the foreseeable heat death of the universe…. So, the question can and must be rephrased: 'Why will our brief 'something' so soon be replaced with nothing?' It's only once we shake our own innate belief in linear progression and consider the many recessions we have undergone and will undergo that we can grasp the gross stupidity of those who repose their faith in divine providence and godly design."

The dialectical usefulness of clear logic, coupled to elegant prose (layered on top of the usual dollop of data), cannot be overstated and should be considered by scientists as another instrument of persuasion in the battle for ideas.

November 2, 2010

The Eternally Boring Hereafter

/// ATTENTION! Spoiler Alert! ///

After a string of highly successful and critically acclaimed films by Clint Eastwood (Million Dollar Baby, Gran Torino, Invictus, Flags of Our Fathers, Letters from Iwo Jima, etc.), I fully expected his latest, Hereafter, to be so well written (screenplay by Peter Morgan—Frost/Nixon, The Queen) and so compelling that stories about near-death experiences would skyrocket and that I would be preoccupied for months dealing with media inquiries about "true stories" of the hereafter. Alas, and with some relief, this will not happen as Hereafter is possibly the worst film Eastwood has ever directed.

If the hereafter is anything like its filmic namesake, then it will turn out to be glacially slow, eternally boring, and pointless, with seemingly random plot lines aimlessly wandering about the ethereal landscape. I wanted to like this film, despite my skepticism on its subject, because I like Clint Eastwood productions and I'm a sucker for a well-produced story, able and willing to suspend disbelief long enough to get emotionally involved. I tried but failed to do so with this film. It's a bomb. Don't bother to see it in the theaters, and don't even waste a couple of bucks on a Netflix rental.

The only redeeming part of the film was the striking opening scene of the tsunami in Southeast Asia that sets the background for the first plot line. An attractive French reporter leaves her lover in their hotel room to go shopping for his kids among the street vendors below. When he hears a disturbing sound and looks out the window he sees the ocean receding, followed by a massive body of water rushing back in to the shore and slamming into buildings and leveling everything in its path. From the woman's street level view tucked in among buildings she can only see trees felling and chaos approaching with only enough time to realize that there is no time to do anything about it. She is swept up in the tsunami's leading edge and slammed about cars, building debris, trees, and the like, until she is whacked on the head unconscious. Cut to minutes later when she is being given mouth-to-mouth resuscitation by rescuers, to no avail. They give up and move on to the next victim, whereupon she comes to life, after a brief encounter with the hereafter, which Eastwood portrays as a fuzzy, nebulous place with people walking about aimlessly. It's a portent of things to come.

The second plot line is Matt Damon's psychic character George, a former psychic who gave up fame and riches because his "gift" is also a curse. A cross between James Van Praagh and John Edward, George concedes to a reading for a client of his sleazy brother (Jay Mohr) and scores several hits. The brother encourages George to quit his job at a San Francisco dock and return to the psychic world, but he will have none of it as it's just too emotionally traumatic to read people's inner thoughts (that much I suspect is true, if any of it were true, which it isn't). Matt Damon's love interest is the beautiful Bryce Dallas Howard, whom he meets at a cooking class, but after nearly an hour's worth of romantic buildup to some sort of coming together, she departs the film for good after George reads her and conveys the message that her deceased father is sorry for the naughty things he did to her as a young girl.

The third plot line develops around 12-year old twins named Marcus and Jason, who live with their drug-addicted mother in London, England. Jason is hit by a car and killed, leaving Marcus to wander about the city in search of a psychic who can connect him to his brother. Here at least Eastwood had the good sense to depict what most psychics are like—scammers and flimflam artists conning their marks out of a few bucks by talking twaddle with the dead through standard cold-reading techniques. Marcus is dismayed by the idiocy of these pretenders and finally returns to the foster home where he struggles to keep his sanity.

For an hour and forty-five minutes all three of these plot lines run parallel, leaving audience members to wonder when—oh please when?!—will they finally be brought together. Finally, after what feels like an interminable marathon of tedium, George quits his job and takes a vacation in London to visit the home of his favorite author, Charles Dickens. While there he notices a flyer for a lecture about Dickens at a book fair in London, where, per chance, the French reporter is doing a signing for her new book on life after death, which she was inspired to write after an hour and a half of futzing around with her mundane reporter's job distracted by her experience with the hereafter in the tsunami. By chance, little Marcus finds himself drawn to the book fair where he recognizes George from his web page photos, and begs him for a reading, which he finally gets. Naturally, George is better than those phony psychics, and Marcus encourages George to seek out the French woman so that they may all connect to the dead. George and Marie find a love connection as well and the story ends happily ever after.

Never have I been so relieved for a movie to end. There was one memorable moment, however, and that was the opening line of the opening trailer before Hereafter even started. The trailer was for a January 2011 release called The Rite, staring Anthony Hopkins as an American priest who travels to Italy to study at an exorcism school. (You can watch the trailer here). The line that rather caught my attention as I was settling into my seat, was, "You know the interesting thing about skeptics?" To which I blurted out "No, what?" The answer: "It's that we're always looking for proof. The question is, What on earth would we do with it if we found it?" I know what I do with proof when I find it. I publish it! Another character in the trailer then says "I believe people prefer to lie to themselves than face the truth."

Here, then, in this trailer is the message for belief in the hereafter. If there were proof of it, we would publish it to the high heavens. But, since there isn't, most people prefer to lie to themselves about it rather than face the truth that it is what we do in this life that counts.

October 19, 2010

6,895

When I matriculated at Pepperdine University in 1974 and moved to the Malibu campus from my home in La Canada, my mother exercised her parental right to express her angst at my departure from the nest, now empty.

I responded with typical teenage indifference and bafflement born of ignorance. "Sheez, Mom, I'm only an hour away. What's the big deal?"

"You just wait until you have one of your own," she cried. "Then you'll know what I'm feeling."

Last month I found out when my daughter moved into her dorm at college and life as I know it has come to an end. Or so at least that's what it feels like. I find myself waking up at four in the morning, reaching for some distracting literature and finding light comfort in Anthony Bourdain's Kitchen Confidential. I entertain a fantasy of riding my bike to Mount Wilson and hurling myself off the cliff fully clipped into my pedals, sans helmet. I turn to the Internet for advice and find this on netdoctor.co.uk ("empty-nest syndrome"): "you could have a long lie in a scented bath. You may even come to see that although you've lost a teenager, you've gained a bathroom!" Oh, great, I've got a woman's disorder. I flip back to Bourdain and learn never to order fish on Mondays (weekend leftovers).

The nest's empty loneliness is almost unbearable. Why does it hurt so bad? Science has an answer: we are social mammals who experience deep attachment to our fellow friends and family, an evolutionary throwback to our Paleolithic hunter-gatherer days of living in small bands of a couple of dozen to a couple of hundred people who were either related to one another or knew one another intimately. Bonding unified the group, aiding survival in harsh climes and against unforgiving enemies, and attachment between parent and offspring assured that there is no one better equipped to look after the future survival of your genes than yourself. We are a pair-bonded species, practicing monogamy (or at least serial monogamy) long enough to get our children out of childhood.

How long is that? In the modern world it's a long time. In my case, from birth to college was 6,895 days, or just a shade under 18.9 years. (For you numerophiles, that's 165,480 hours, or 9,928,800 minutes, or 595,728,000 seconds). The quantitative figures do not begin to capture the qualitative feeling of bonding that happens between a parent and a child from the sheer amount of time spent together. Think about what those numbers mean. Every day for 6,895 days, when you get up and around in the morning your primary duty in life is to assure your child's care and safety. An unbroken chain, suddenly cut.

We parents can't help feeling this way and neuroscience explains why: there are a number of addictive chemicals such as dopamine and oxytocin that surge through the brain and body during positive social interactions (especially touch) that causes us to feel closer to one another. As my colleague at Claremont Graduate University Paul Zak has demonstrated in his lab, between strangers oxytocin creates a feeling of friendship. Between couples it leads to attraction and love. Between parents and offspring it cements a bond so solid that it is broken only under the most unusual (and usually pathological) circumstances. Mothers of serial killers have been known to weep in court and plead for leniency, even in the presence of the mothers of the murdered victims.

The empty-nest syndrome is real, but there is good news for this and all forms of loss and grief. According to the Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert, we are not very good at forecasting our unhappiness. In a comprehensive study involving six different experiments, Gilbert and his colleagues asked subjects to imagine how they would feel in a number of different scenarios that one could reasonably expect would trigger negative emotions, including the breakup of a romantic relationship, the failure to earn tenure, a defeat in a political election, negative feedback on one's personality, the death of a child, and a job rejection by a prospective employer. Most of us think that we would be miserable for a very long time. Gilbert calls this the durability bias, an emotional misunderstanding. "Common events typically influence people's subjective well-being for little more than a few months, and even uncommon events—such as losing a child in a car accident, being diagnosed with cancer, becoming paralyzed, or being sent to a concentration camp—seem to have less impact on long-term happiness than one might naively expect."

In such situations we seem to experience immune neglect, says Gilbert, where we neglect to consider the strength of our psychological immune systems to protect us against the pain of insult, defeat, regret, and loss. In his experiments, for example, Gilbert and his colleagues found that "students, professors, voters, newspaper readers, test takers, and job seekers overestimated the duration of their affective reactions to romantic disappointments, career difficulties, political defeats, distressing news, clinical devaluations, and personal rejections."

The durability bias and the failure to recognize the power of our emotional immune systems leads us to overestimate how dejected we will feel and for how long, and to underestimate how quickly we will snap out of it and feel better.

For me, taking the long view helps. How long? Deep time. Evolutionary time, in which 6,895 days represents a mere .000000005 percent of the 3.5 billion-year history of life on earth. Each of us parents makes one small contribution to the evolutionary imperative of life's continuity from one generation to the next without a single gap, an unbroken link over the eons, glorious in its contiguity and spiritual in its contemplation.

And always remember, there's no place like home…

October 13, 2010

Can You Hear Me Now?

Baseball legend Yogi Berra is said to have fretted, "I don't want to make the wrong mistake." As opposed to the right mistake? A mistake that is both wrong and right is the alleged connection between cell phone use and brain cancers. Reports of a link between the two have periodically surfaced ever since cell phones became common appendages to people's heads in the 1990s. As recently as this past May 17, Time magazine reported that despite numerous studies finding no connection between cell phones and cancer, "a growing band of scientists are skeptical, suggesting that the evidence that does exist is enough to raise a warning for consumers — before mass harm is done."

Their suggestion follows the precautionary principle, which holds that if something has any potential for great harm to a large number of people, then even in the absence of evidence of harm, the burden of proof is on the unworried to demonstrate that the danger is not real. The precautionary principle is a weak argument for two reasons: (1) it is difficult to prove a neg ative — that there is no effect; (2) it raises unnecessary public alarm and personal anxiety. Cell phones and cancer is a case study in the precautionary principle misapplied, because not only is there no epidemiological evidence of a causal connection, but physics shows that it is virtually impossible for cell phones to cause cancer.

The latest negative findings mentioned by Time come out of a $24-million research project published in the International Journal of Epidemiology ("Brain Tumour Risk in Relation to Mobile Telephone Use"). It encompassed more than 12,000 long-term regular cell phone users from 13 countries, about half of whom were brain cancer patients, which let researchers compare the two groups. The authors concluded: "Overall, no increase in risk of glioma or meningioma [the two most common types of brain tumors] was observed with use of mobile phones. There were suggestions of an increased risk of glioma at the highest exposure levels, but biases and error prevent a causal interpretation. The possible effects of longterm heavy use of mobile phones require further investigation." This application of the precautionary principle is the wrong mistake to make. Cell phones cannot cause cancer, because they do not emit enough energy to break the molecular bonds inside cells. Some forms of electromagnetic radiation, such as x-rays, gamma rays and ultraviolet (UV) radiation, are energetic enough to break the bonds in key molecules such as DNA and thereby generate mutations that lead to cancer. Electromagnetic radiation in the form of infrared light, microwaves, television and radio signals, and AC power is too weak to break those bonds, so we don't worry about radios, televisions, microwave ovens and power outlets causing cancer.

Where do cell phones fall on this spectrum? According to physicist Bernard Leikind in a technical article in Skeptic magazine (Vol. 15, No. 4), known carcinogens such as x-rays, gamma rays and UV rays have energies greater than 480 kilojoules per mole (kJ/mole), which is enough to break chemical bonds. Greenlight photons hold 240 kJ/mole of energy, which is enough to bend (but not break) the rhodopsin molecules in our retinas that trigger our photosensitive rod cells to fire. A cell phone generates radiation of less than 0.001 kJ/mole. That is 480,000 times weaker than UV rays and 240,000 times weaker than green light!

Even making the cell phone radiation more intense just means that there are more photons of that energy, not stronger photons. Cell phone photons cannot add up to become UV photons or have their effect any more than microwave or radio-wave photons can. In fact, if the bonds holding the key mole cules of life together could be broken at the energy levels of cell phones, there would be no life at all because the various natural sources of energy from the environment would prevent such bonds from ever forming in the first place.

Thus, although in principle it is difficult to prove a negative, in this case, one can say it is impossible for cell phones to hurt the brain — with the exception, of course, of hitting someone on the head with one. QED.

October 12, 2010

Touching History

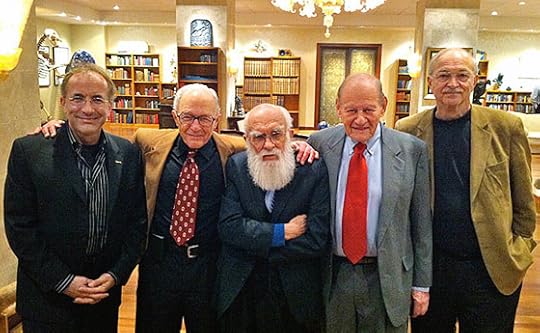

Skeptical Luminaries right to left: paranormal investigator Joe Nickell, Center for Inquiry founder Paul Kurtz, the Amazing One himself, and psychologist and magician Ray Hyman

On Sunday, October 3, a group of skeptics gathered in Falls Church, Virginia to celebrate James Randi's 82nd birthday. What an amazing meeting it was … er, an astonishing evening I mean, as Randi prefers to retain the "amazing" adjective for his moniker, James "The Amazing" Randi. Take a look at just a few of the giants present in the above photo — the legends of skepticism (from right to left: paranormal investigator Joe Nickell, Center for Inquiry founder Paul Kurtz, the Amazing One himself, and psychologist and magician Ray Hyman).

click any of the following thumbnail images to enlarge

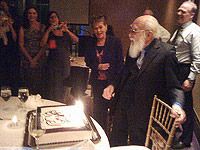

Also in attendance were Richard Dawkins, the magician Jamy Ian Swiss, the President of the James Randi Educational Foundation (JREF) D. J. Grothe, and many other skeptical luminaries from around the world, many of whom sang Randi's praises in the tribute portion of the evening. Randi was presented with a beautiful birthday cake with his inimitable likeness on the icing, and something well short of 82 candles on top to blow out, which he managed successfully.

After dinner we all adjourned to the private library of a good friend of Randi and benefactor of JREF, who kindly allowed us to peruse his collection of some of the rarest books in the history of science, along with other spectacular items of considerable interest. It is, in short, the finest collection I have ever seen anywhere in the world. Any single volume on any of the shelves would be an item worthy of possession as one's most cherished belonging, and here there were hundreds of such treasures.

How's this for starters?: The Archimedes Palimpsest, purchased at auction for $2.2 million. Check out the two sets of lines on this page: one set of bold lines in Latin that was a medieval prayer book, and the other lighter lines in Greek that was nothing less than one of the most important treatises ever published by the ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes. I highly recommend the book, The Archimedes Codex, by Reviel Netz and William Noel, that uncovers the mystery story of how this book came to auction, and the scientific detective story of how Archimedes ancient words were coaxed back to life. (Quality paper for publishing was so rare in the Middle Ages that older books were reused by scraping off the text and reprinting over it.)

If that isn't awe inspiring enough, check out the photo of a page from an ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead that Joe Nickell and I are examining. Because papyrus paper is so delicate this one is under glass (so we couldn't "touch history" directly in this case), but Joe and I were trying to find Randi's name in there somewhere…

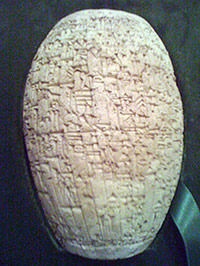

Talk about touching some old stuff, look at this many millennia-old Babylonian cylinder with cuneiform writing on it, apparently an ancient calculator of sorts (if memory serves … it was a heady evening trying to take in all these treasures).

Going back tens of thousands of years, look at the magnificent Wholly Mammoth tusk, and guess what that is in my hand: yes, that's Wholly Mammoth hair. Is there a lab somewhere in the world who could take the DNA from that hair and clone a mammoth back to life? Forget Jurassic Park; I'd settle for Paleolithic Land.

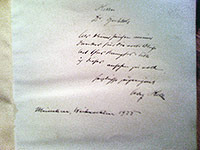

Given my interest in World War II and all things Nazi, which I had to learn in researching my book Denying History (about the Holocaust deniers), this item made the hair on the back of my neck stand up: it's a first edition of Mein Kampf. This one in particular was signed by Adolf Hitler to "Dr. Goebbels", 1925. Next to it is another first edition addressed in Hitler's hand to Hermann Goering.

As well, the library contains two Nazi enigma code machines, designed and built for encryption and decryption of messages and was used during the Second World War. The cracking of the enigma code encryption algorithms by the British led project ULTRA is said to have shortened the war by at least two years, if not being the single most important step toward victory.

There is something about touching history in this way that almost beggars description. It's visceral. Running my fingers over the cuneiform clay cuts in the cylinder while imagining some ancient Babylonian accountant or scribe holding it in one hand while pressing into the wet clay with a small writing stick in the other draws one back in time. Rubbing the tips of my fingers over the parchment paper of medieval manuscripts brings to my inner ear a Gregorian chant wafting through the cold, dank halls of a European monastery with monks keeping alive ancient wisdom through their endless hours of copying the masters.

Visiting this library, in fact, is like a time machine, transporting you back anywhere into the past you like just by touching the spine of a book and pulling it off the shelf. I know, this all sounds so … well … New Ageish. I am a materialist, a monist — someone who does not believe that there is something immaterial like a soul or spirit or essence of a thing that carries on beyond the physical material of its original pattern. But to hold an item of such antiquity and such rarity and originality overwhelms the senses and enthuses the emotions beyond what meager words such as these can convey.

I touched the past and it lived again.

September 21, 2010

God 2.0: Is the deity a nonlocal quantum mind?

Do you believe in God? In most surveys, about nine out of ten Americans respond in the affirmative. The other ten percent provide a variety of answers, including a favorite among skeptics and atheists, "which God?," spoken in a smarmy manner and followed by a litany of deities: Aphrodite, Amon Ra, Apollo, Baal, Brahma, Ganesha, Isis, Mithras, Osiris, Shiva, Thor, Vishnu, Wotan, and Zeus. "We're...

September 7, 2010

What I Believe (about Markets and Morals)

In his endearingly titled blog, "Michael, we hardly knew ye," the venerable evolutionary biologist and slayer of creationist dragons Jerry Coyne (author of Why Evolution is True) wonders if I've gone 'round the bend over capitalism and sold my skeptical soul to the Templeton Foundation, the alleged evil subsidizers of religious and capitalist propaganda. Allow me to set the record straight (again) for all my critics out there (and in reading the comments to Jerry's blog ...

September 6, 2010

Democracy's Laboratory

DO YOU BELIEVE IN EVOLUTION? I do. But when I say "I believe in evolution," I mean something rather different than when I say "I believe in liberal democracy." Evolutionary theory is a science. Liberal democracy is a political philosophy that most of us think has little to do with science.

That science and politics are nonoverlapping magisteria (vide Stephen Jay Gould's model separating science and religion) was long m...

Michael Shermer's Blog

- Michael Shermer's profile

- 1155 followers