Michael Shermer's Blog, page 18

July 19, 2011

Gambling on ET

The Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) has to be the most interesting field of science that lacks a subject to study. Yet. Keep searching. In the meantime, is there some metric we can apply to calculating the probability and impact of claims of such a discovery? There is.

In January, 2011 the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society published 17 articles addressing the matter of "The Detection of Extra-Terrestial Life and the Consequences for Science and Society," including one by Iván Almár from the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and Margaret S. Race from the SETI Institute, introducing a metric "to provide a scalar assessment of the scientific importance, validity and potential risks associated with putative evidence of ET life discovered on Earth, on nearby bodies in the Solar System or in our Galaxy." Such scaling is common in science—the Celsius scale for temperature, the Beaufort scale for wind speed, the Saffir-Simpson scale for hurricane strength, and the Richter scale for earthquake magnitude. But these scales, Almár and Race argue, fail to take into account "the relative position of the observer or recipient of information." The effects of a 7.1 earthquake, for example, depends on the proximity of its epicenter to human habitations.

An improvement may be found in the Torino Scale that computes the likelihood of an asteroid impact and the risk of its potential damage—from 1, a near miss with no danger, to 10, certain impact with catastrophic consequences. But Almár and Race note that "the scale does not include any consideration of the observations' reliability." Building on SETI's Rio Scale for evaluating the effect on society of an ET discovery, Almár and Race propose the London Scale that multiplies Q x δ, where Q (scientific importance) is the sum of four parameters:

life form (1–5, from Earth-similar life to completely alien),

nature of evidence (1-6, from indirect biomarkers

to obviously organized complex life),

type of method of discovery (1–5, from remote sensing

to return mission sample), and

distance (1–4, from beyond the Solar System to on Earth).

This sum is then multiplied by δ (a reliability factor) ranging from 0.1–0.5, from probably not real to highly reliable. The maximum Q can be is 20 x .5 = 10.

For example, Almár and Race compute the odds that the Allan Hills 84001 Martian meteorite contains alien life as (2+2+4+4)0.3 = 3.6 for scientific importance and credibility, noting that "several scientific counter-arguments have been published and the discovery has not been generally accepted." I would assess the recent claim of arsenic-based life in Mono Lake as (2+1+4+4)0.2 = 2.2, fairly low by comparison.

Such scientific scales attempt to bring some rigor and reliability to estimates of events that are highly improbable or uncertain. The process also reveals why most scientists do not take seriously UFO claims. Although the first two categories would yield a 5 and a 6 (completely alien and complex life) and its distance is zero (4, on Earth), the method of discovery is highly subjective (perceptual, psychological) and open to alternative explanation (1, other aerial phenomena) and the reliability factor δ is either obviously fake or fraudulent (0) or probably not real (0.1), and so Q = (5+6+1+4)0.1 = 1.6 (or 0 if δ = 0).

The Phoenix lights UFO claim, for example, was a real aerial phenomena witnessed by thousands on the evening of March 13, 1997. UFOlogists (and even Arizona governor Fife Symington) claim it was extraterrestrial, but what is δ for this event? It turns out that there were two independent aerial events that night, the first a group of planes flying in a "V" formation at 8:30 that started a UFO hysteria and brought people outdoors with video cameras, which then recorded a string of lights at 10:00 that slowly sank until they disappeared behind a nearby mountain range. These turned out to be flares dropped by the Air National Guard on a training mission. Ever since, people have conflated the two events and thereby transmogrified two IFOs into one UFO. So δ = 0 and Q shifts from 1.6 to 0, which is how much confidence I have in UFOlogists until they produce actual physical evidence, the sine qua non of science.

June 28, 2011

19

into a lesson in patternicity and numerology

On Friday, June 17, a film crew came by the Skeptics Society office to interview me for a documentary that I was told was on arguments for and against God. The producer of the film, Alan Shaikhin, sent me the following email, which I reprint here in its entirety so that readers can see that there is not a hint of what was to come in what turned out to be an attempted ambush interview with me about Islam, the Quran, and the number 19:

Dear Michael!

I am the director of a film crew hired by a non-profit organization, Izgi Amal, from Kazakhstan, which has no connection with the American brat, Borat. We have been working on a documentary film on modern philosophical and scientific arguments for and against God for almost a year. We have been taking shots and interviewed theologians, philosophers and scientists in England, Netherlands, USA, Turkey, and Egypt.

We are planning to finish the film by the end of this year and participate in major film festivals, including Cannes. We will allocate some of the funds to distribute thousands of copies of the film for free, especially to libraries and colleges.

Our crew will once again visit the United States and will spend the rest of June interviewing various people, from layman to artists, from academicians to activists.

Though we are far out there, we know your work and we think that it contributes greatly to the quality of this perpetual philosophical debate. We would like to include perspective and voice in this discussion. We would appreciate if you let us know what days in JUNE would be the best dates to meet you and interview you for this engaging and fascinating documentary film.

Since we are planning to interview about 10 scholars and experts of diverse positions such as atheism, agnosticism, deism, monotheism, and polytheism, it is important to learn all available days in this month of June.

Please feel free to contact us via email or our cell phone numbers, below. If you respond via email and please let us know the best phone number and times to reach you.

Peace,

Alan Shaikhi

In hindsight perhaps I should have picked up on his admission that "we are far out there," which in fact they turned out to be. Present were Mr. Shaikhin, another gentleman named Edip Yuksel, a couple of film crew hands, and a woman videographer who was setting up all the lighting and equipment. Before we began Shaikhin explained that they were actually filming two projects, and that his colleague (Mr. Yuksel) would be interviewing me after he, Shaikhin, was finished. Yuksel, in fact, was very fidgety and throughout the interview with Shaikhin I could see him out of the corner of my eye feverishly taking notes and fiddling around with books whose titles I could not see.

Shaikhin's interview, in fact, included mostly standard faire questions for such documentaries: Do I think there's a conflict between science and religion?, What do I think about this and that argument for God's existence?, Why do I think people believe in God?, etc. He was unfailingly polite and professional. Toward the end he did make some vague reference to Islam and our cover story of Skeptic on myths about the Islamic religion (the myth of the Middle East Madman, the myth of the 72 virgins, etc.), but I begged off answering anything about Islam because I haven't studied it much nor have I read the Quran.

My first clue that the interview was about to take a sharp right turn came when Shaikhin acted shocked that I would edit an issue of Skeptic on Islam without myself having read the Quran. I explained that I write very few articles in Skeptic and that my job as editor is to find writers who are experts on a subject, which was, in fact, the case with this issue when our Senior Editor Frank Miele interviewed the University of California at Santa Barbara Islamic scholar R. Stephen Humphreys. Nonetheless, Shaikhin continued to act surprised, repeating "you mean to tell me that you edited a special issue of Skeptic on Islam and haven't read the Quran?" I again explained that editors of magazines are not always (or ever) the world's leading expert on the topics they publish, which is the very reason for contracting with experts to write the articles for magazines.

With this first part of the interview completed, Edip Yuksel leaped up out of his chair like a WWF wrestler charging into the ring for his big match. He grabbed a chair and pulled it over next to mine, asked for a bottle of water for the match, and instructed the videographer to widen the shot to include him in the interview. Only it wasn't an interview. It was a monologue, with Yuksel launching into a mini-history of how he wrote Carl Sagan back in 1992 about the number 19 (he didn't say if Sagan ever wrote back), how Carl had written about the deep significance of the number π (pi) in his science fiction novel Contact, how he is a philosopher and a college professor who teaches his students how to think critically, and that he is a great admirer of my work. However (you knew this was coming, right?), there is one thing we should not be skeptical about, and that is the remarkable properties of the number 19 and the Quran.

At this point I had a vague flashback memory of the Million Man March in Washington, D.C. and Louis Farrakhan's musings about the magical properties of the number 19. The transcript from that speech confirmed my memory. Here are a few of the numerological observations by Farrakhan that day in October, 1995:

There, in the middle of this mall is the Washington Monument, 555 feet high. But if we put a one in front of that 555 feet, we get 1555, the year that our first fathers landed on the shores of Jamestown, Virginia as slaves.

In the background is the Jefferson and Lincoln Memorial, each one of these monuments is 19 feet high.

Abraham Lincoln, the sixteenth president. Thomas Jefferson, the third president, and 16 and three make 19 again. What is so deep about this number 19? Why are we standing on the Capitol steps today? That number 19—when you have a nine you have a womb that is pregnant. And when you have a one standing by the nine, it means that there's something secret that has to be unfolded.

I want to take one last look at the word atonement.

The first four letters of the word form the foundation; "a-t-o-n" … "a-ton", "a-ton". Since this obelisk in front of us is representative of Egypt. In the 18th dynasty, a Pharaoh named Akhenaton, was the first man of this history period to destroy the pantheon of many gods and bring the people to the worship of one god. And that one god was symboled by a sun disk with 19 rays coming out of that sun with hands holding the Egyptian Ankh – the cross of life. A-ton. The name for the one god in ancient Egypt. A-ton, the one god. 19 rays.

This is a splendid example of what I call patternicity: the tendency to find meaningful patterns in both meaningful and meaningless noise. And Edip Yuksel launched into a nonstop example of patternicity when he pulled out his book entitled Nineteen: God's Signature in Nature and Scripture (2011, Brainbow Press; see also www.19.org) and began to quote from it. To wit…

The number of Arabic letters in the opening statement of the Quran, BiSMi ALLaĤi AL-RaĤMaNi AL-RaĤYM (1:1) 19

Every word in Bismillah… is found in the Quran in multiples of 19

The frequency of the first word, Name (Ism) 19

The frequency of the second word, God (Allah) 19 x 142

The frequency of the third word, Gracious (Raĥman) 19 x 3

The fourth word, Compassionate (Raĥym) 19 x 6

Out of more than hundred attributes of God, only four has numerical values of multiple of 19

The number of chapters in the Quran 19 x 6

Despite its conspicuous absence from Chapter 9, Bismillah occurs twice in Chapter 27, making its frequency in the Quran 19 x 6

Number of chapters from the missing Ch. 9 to the extra in Ch. 27. 19 x 1

The total number of all verses in the Quran, including the 112 unnumbered Bismillah 19 x 334

Frequency of the letter Q in two chapters it initializes 19 x 6

The number of all different numbers mentioned in the Quran 19 x 2

The number of all numbers repeated in the Quran 19 x 16

The sum of all whole numbers mentioned in the Quran 19 x 8534

This goes on and on for 620 pages which, when divided by the number of chapters in the book (31) equals 20, which is one more than 19; since 1 is the cosmic number for unity, the first nonzero natural number, and according to the rock group Three Dog Night the loneliest number, we subtract 1 from 20 to once again see the power of 19. In fact, 19 is a prime number, it is the atomic number for potassium (flip that "p" to the left and you get a 9), in the Baha'i faith there were 19 disciples of Baha'u'llah and their calendar year consists of 19 months of 19 days each (361 days), and it's the last year you can be a teenager and the last hole in golf that is actually the clubhouse bar. In point of fact we can find meaningful patterns with almost any number:

99: names of Allah; atomic number for Einsteinium; Agent 99 on TV series Get Smart

40: 40 days and 40 nights of rain; Hebrews lived 40 years in the desert, Muhammad's age when he received the first revelation from the Archangel Gabriel and the number of days he spent in the desert and days he spent fasting in a cave

23: The 23 enigma: the belief that most incidents and events are directly connected to the number 23

11: sunspot cycle in years, the number of Jesus's disciples after Judas defected

7: 7 deadly sins and 7 heavenly virtues; Shakespeare's 7 ages of man, Harry Potter's most magical number

3: number of dimensions; the first prime number, number of sides of a triangle, the 3 of clubs—the forced pick in one of Penn & Teller's favorite card tricks

1: unity; the first non-zero natural number, it's own factorial and it's own square; the atomic number of hydrogen; the most abundant element in the universe; Three Dog Night's song about the loneliest number

π (pi): a mathematical constant whose value is the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter, or 3.13159…. Make of this what you will, but Carl Sagan did elevate π to significance at the end of Contact:

The universe was made on purpose, the circle said. In whatever galaxy you happen to find yourself, you take the circumference of a circle, divide it by its diameter, measure closely enough, and uncover a miracle—another circle, drawn kilometers downstream of the decimal point. In the fabric of space and in the nature of matter, as in a great work of art, there is, written small, the artist's signature. Standing over humans, gods, and demons, subsuming Caretakers and Tunnel builders, there is an intelligence that antedates the universe.

At this point in the filming process I interrupted Yuksel and told Shaikhin that the interview was over, that he could use the footage from the first part of the interview but not this monologue mini-lecture that was an undisguised attempt to convince me of the miraculous properties of the number 19. I didn't sign any waiver or permission to use any of the footage shot that day, but just in case I was relieved when the videographer came to me in private to apologize and explain that she had nothing to do with the rest of the crew, that she was just hired to do the filming, and that after I had put an end to the interview she stopped filming.

At some point I asked Edip why he felt so compelled to convince me of the meaningfulness of the number 19 in the Quran, when I told him that I haven't read the Quran and hold that all such numerological searches are nothing more than patternicity. The impression I got was that if he could convince a professional skeptic then there must be something to the claim. I asked him what other Islamic scholars who have read the Quran think of his claims for the number 19, and he told me that they consider him a heretic. He said it as a point of pride, as if to say "the fact that the experts denounce me means that I must be on to something."

P.S. Edip Yuksel did strike me as a likable enough fellow who seemed genuinely passionate about his beliefs, but there was something a bit off about him that I couldn't quite place until I was escorting him out of the office and he said, "I see you are a very athletic fellow. Can I show you something that I learned in a Turkish prison?" With scenes from Midnight Express flashing through my mind, I muttered "Uhhhhhh… No."

Patternicity Challenge to Readers

As a test—of sorts—I would like to hereby issue a challenge to all readers to employ their own patternicity skills at finding meaningful patterns in both meaningful and meaningless noise with such numbers and numerical relationships, both serious and lighthearted, related to the number 19 or any other number that strikes your fancy. Post them here and we shall publish them in a later feature-length article I shall write on this topic.

June 16, 2011

Center for Inquiry hosts Shermer in NY on The Believing Brain

On June 9, 2011, the Center for Inquiry (New York City) and NYC Skeptics hosted noted skeptic and bestselling author Michael Shermer for a talk about his new book, The Believing Brain: From Ghosts and Gods to Politics and Conspiracies—How We Construct Beliefs and Reinforce Them as Truths. The event was held at the Auditorium on Broadway. Full lecture, followed by Q&A.

June 1, 2011

The Myth of the Evil Aliens

about extraterrestrial intelligences

WITH THE ALIEN TELESCOPE ARRAY run by the SETI Institute in northern California, the time is coming when we will encounter an extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI). Contact will probably come sooner rather than later because of Moore's Law (proposed by Intel's co-founder Gordon E. Moore), which posits a doubling of computing power every one to two years. It turns out that this exponential growth curve applies to most technologies, including the search for ETI (SETI): according to astronomer and SETI founder Frank Drake, our searches today are 100 trillion times more powerful than 50 years ago, with no end to the improvements in sight. If E.T. is out there, we will make contact. What will happen when we do, and how should we respond?

Such questions, once the province of science fiction, are now being seriously considered in the oldest and one of the most prestigious scientific journals in the world—Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A—which devoted 17 scholarly articles to "The Detection of Extra-Terrestrial Life and the Consequences for Science and Society" in its February issue. The myth, for example, that society will collapse into fear or break out in pandemonium—or that scientists and politicians will engage in a conspiratorial cover-up—is belied by numerous responses. Two such examples were witnessed in December 2010, when NASA held a very public press conference to announce a possible new life-form based on arsenic, and in 1996, when scientists proclaimed that a Martian rock contained fossil evidence of ancient life on the Red Planet and President Bill Clinton made a statement on the topic. Budget-hungry space agencies such as NASA and private fund-raising organizations such as the SETI Institute will shout to the high heavens about anything extraterrestrial they find, from microbes to Martians. But should we shout back to the aliens?

According to Stephen Hawking, we should keep our mouths shut. "We only have to look at ourselves to see how intelligent life might develop into something we wouldn't want to meet," he noted in his 2010 Discovery Channel documentary series. "I imagine they might exist in massive ships, having used up all the resources from their home planet. Such advanced aliens would perhaps become nomads, looking to conquer and colonize whatever planets they can reach." Given the history of encounters between earthly civilizations in which the more advanced enslave or destroy the less developed, Hawking concluded: "If aliens ever visit us, I think the outcome would be much as when Christopher Columbus first landed in America, which didn't turn out very well for the Native Americans."

I am skeptical. Although we can only represent the subject of an N of 1 trial, and our species does have an unenviable track record of first contact between civilizations, the data trends for the past half millennium are encouraging: colonialism is dead, slavery is dying, the percentage of populations that perish in wars has decreased, crime and violence are down, civil liberties are up, and, as we are witnessing in Egypt and other Arab countries, the desire for representative democracies is spreading, along with education, science and technology. These trends have made our civilization more inclusive and less exploitative. If we extrapolate that 500-year trend out for 5,000 or 500,000 years, we get a sense of what an ETI might be like.

In fact, any civilization capable of extensive space travel will have moved far beyond exploitative colonialism and unsustainable energy sources. Enslaving the natives and harvesting their resources may be profitable in the short term for terrestrial civilizations, but such a strategy would be unsustainable for the tens of thousands of years needed for interstellar space travel. In this sense, thinking about extraterrestrial civilizations forces us to consider the nature and progress of our terrestrial civilization and offers hope that, when we do make contact, it will mean that at least one other intelligence managed to reach the level where harnessing new technologies displaces controlling fellow beings and where exploring space trumps conquering land. Ad astra!

May 31, 2011

Demographics of Belief

The following excerpt is from the Prologue to my new book, The Believing Brain: From Ghosts, Gods, and Aliens to Conspiracies, Economics, and Politics—How the Brain Constructs Beliefs and Reinforces Them as Truths. The Prologue is entitled "I Want to Believe." The book synthesizes 30 years of research to answer the questions of how and why we believe what we do in all aspects of our lives, from our suspicions and superstitions to our politics, economics, and social beliefs. LEARN MORE about the book.

Order the hardcover from shop.skeptic.com

According to a 2009 Harris Poll of 2,303 adult Americans, when people are asked to "Please indicate for each one if you believe in it, or not," the following results were revealing:1

82% believe in God

76% believe in miracles

75% believe in Heaven

73% believe in Jesus is God

or the Son of God

72% believe in angels

71% believe in survival

of the soul after death

70% believe in the

resurrection of Jesus Christ

61% believe in hell

61% believe in

the virgin birth (of Jesus)

60% believe in the devil

45% believe in Darwin's

Theory of Evolution

42% believe in ghosts

40% believe in creationism

32% believe in UFOs

26% believe in astrology

23% believe in witches

20% believe in reincarnation

Wow. More people believe in angels and the devil than believe in the theory of evolution. That's disturbing. And yet, such results should not surprise us as they match similar survey findings for belief in the paranormal conducted over the past several decades.2 And it is not just Americans. The percentages of Canadians and Britons who hold such beliefs are nearly identical to those of Americans.3 For example, a 2006 Readers Digest survey of 1,006 adult Britons reported that 43 percent said that they can read other people's thoughts or have their thoughts read, more than half said that they have had a dream or premonition of an event that then occurred, more than two-thirds said they could feel when someone was looking at them, 26 percent said they had sensed when a loved-one was ill or in trouble, and 62 percent said that they could tell who was calling before they picked up the phone. In addition, a fifth said they had seen a ghost and nearly a third said they believe that Near-Death Experiences are evidence for an afterlife.4

Although the specific percentages of belief in the supernatural and the paranormal across countries and decades varies slightly, the numbers remain fairly consistent that the majority of people hold some form of paranormal or supernatural belief.5 Alarmed by such figures, and concerned about the dismal state of science education and its role in fostering belief in the paranormal, the National Science Foundation (NSF) conducted its own extensive survey of beliefs in both the paranormal and pseudoscience, concluding with a plausible culprit in the creation of such beliefs:

Belief in pseudoscience, including astrology, extrasensory perception (ESP), and alien abductions, is relatively widespread and growing. For example, in response to the 2001 NSF survey, a sizable minority (41 percent) of the public said that astrology was at least somewhat scientific, and a solid majority (60 percent) agreed with the statement "some people possess psychic powers or ESP." Gallup polls show substantial gains in almost every category of pseudoscience during the past decade. Such beliefs may sometimes be fueled by the media's miscommunication of science and the scientific process.6

I too would like to lay the blame at the feet of the media, or science education in general, because the fix then seems straightforward—just improve how we communicate and educate science. But that's too easy. In any case, the NSF's own data do not support it. Although belief in ESP decreased from 65% among high school graduates to 60% among college graduates, and belief in magnetic therapy dropped from 71% among high school graduates to 55% among college graduates, that still leaves over half of educated people fully endorsing such claims! And for embracing alternative medicine, the percentages actually increased, from 89% for high school grads to 92% for college grads.

Perhaps a deeper cause may be found in another statistic: 70% of Americans still do not understand the scientific process, defined in the NSF study as grasping probability, the experimental method, and hypothesis testing. So one solution here is teaching how science works in addition to the rote memorization of scientific facts. A 2002 article in Skeptic magazine entitled "Science Education is No Guarantee of Skepticism," presented the results of a study that found no correlation between science knowledge (facts about the world) and paranormal beliefs. The authors, W. Richard Walker, Steven J. Hoekstra, and Rodney J. Vogl, concluded: "Students that scored well on these [science knowledge] tests were no more or less skeptical of pseudoscientific claims than students that scored very poorly. Apparently, the students were not able to apply their scientific knowledge to evaluate these pseudoscientific claims. We suggest that this inability stems in part from the way that science is traditionally presented to students: Students are taught what to think but not how to think."7 The scientific method is a teachable concept, as evidenced in the NSF study that found that 53% of Americans with a high level of science education (nine or more high school and college science/math courses) understand the scientific process, compared to 38% with a middle level (six to eight such courses) of science education, and 17% with a low level (less than five such courses) of science education. So maybe the key to attenuating superstition and belief in the supernatural is in teaching how science works, not just what science has discovered. I have believed this myself for my entire career in science and education. If I didn't believe it I might not have gone into the business of teaching, writing, and editing science in the first place.

Alas, I have come to the conclusion that belief is largely immune to attack by direct educational tools, at least for those who are not ready to hear it. Belief change comes from a combination of personal psychological readiness and a deeper social and cultural shift in the underlying zeitgeist of the times, which is affected in part by education, but is more the product of larger and harder-to-define political, economic, religious, and social changes.

DOWNLOAD my reading of the prologue (48MB MP3)

FOLLOW me on Twitter

References

www.harrisinteractive.com/vault/Harris_Poll_2009_12_15.pdf

www.gallup.com/poll/16915/Three-Four-Americans-Believe-Paranormal.aspx

Similar percentages of belief were found in this 2005 Gallup Poll:

Psychic or Spiritual Healing

55%

Demon possession

42%

ESP

41%

Haunted Houses

37%

Telepathy

31%

Clairvoyance (know past/predict future)

26%

Astrology

25%

Psychics are able to talk to the dead

21%

Reincarnation

20%

Channeling spirits from the other side

9%

www.gallup.com/poll/19558/Paranormal-Beliefs-Come-SuperNaturally-Some.aspx

news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/5017910.stm

Gallup News Service. 2001. "Americans' Belief in Psychic Paranormal Phenomena is up Over Last Decade." June 8.

National Science Foundation. 2002. Science Indicators Biennial Report. The section on pseudoscience, "Science Fiction and Pseudoscience," is in Chapter 7. Science and Technology: Public Understanding and Public Attitudes. Go to: www.nsf.gov/sbe/srs/seind02/c7/c7h.htm.

Walker, W. Richard, Steven J. Hoekstra, and Rodney J. Vogl. 2002. "Science Education is No Guarantee of Skepticism." Skeptic, Vol. 9, No. 3, 24–25.

May 17, 2011

Apocalypse Redux

The following article originally ran in the Wall Street Journal on Saturday, May 14, one week before Judgment Day is to arrive. The following essay is a longer and more detailed version of the story.

May 21, 2011 is the latest in a long line of predictions of the end of the world. What drives doomsayers, both religious and secular?

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

—William Butler Yeats, "The Second Coming"

God…now commandeth all men every where to repent because He has appointed a day in which He will judge the world.

—Acts, 17:30–31

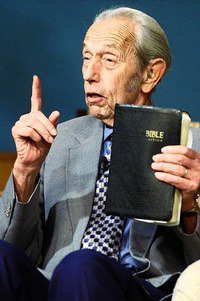

Harold Camping in 2002

That day is Saturday, May 21, says the Oakland, California-based evangelical Christian Family Radio host Harold Camping. By his calculations, May 21, 2011 marks the beginning of end of the world, when Jesus returns to judge us all and rapture those who believe in Him. How did Camping arrive at this date? Genesis 7:4 states that, "Seven days from now I will send rain on the earth for forty days and forty nights, and I will wipe from the face of the earth every living creature I have made." Seven days is actually 7,000 years because in 2 Peter 3:8 it notes that a day is as a thousand years. (Although apparently 40 days is not 40,000 years of rain.) The Noachian flood unleashed its rain of terror in 4990 B.C., so if you add 7,000 years minus 1 (because there was no year zero), you arrive at 2011. Camping claims that May 21 is the 17th day of the 2nd month of the Hebrew calendar, from which the biblical chronology of the flood is determined. Therefore, May 21 is the Big Day.

If you are still around on May 22, it means you are not one of the chosen. But there still may be time to repent before October 21, when the physical end of the world comes. What will happen when that prophecy also fails? (Camping previously predicted September 6, 1994 as Judgment Day.) Doomsayers are nothing if not resourceful. (I mean this in both senses—according to GuideStar.org, which monitors nonprofit assets, Camping's organization is worth over $100 million, raking in a cool $18 million in 2009). Not only do they not admit when they are wrong, they become even more adamant about the verisimilitude of their beliefs, spin-doctoring the nonevent into a successful prophecy, with such rationalizations as these previously employed gems:

Miscalculation of the date.

The date was a loose prediction, not a specific prophecy.

The date was more of a warning than a prophecy.

God changed his mind in response to members' prayers.

The prophecy was just a test of members' faith.

The prophecy was fulfilled physically, but not as expected.

The prophecy was fulfilled spiritually, but not recognized.

Thus it is that Jesus' first-century prophecy (in Matthew 16:28) that, "There shall be some standing here, which shall not taste of death, till they see the Son of man coming in his kingdom," did not attenuate in the least belief in the Second Coming for the past two millennia. Hundreds of predictions have been made, with the Jehovah's Witnesses possibly holding the record for the most failed dates of doom: 1874, 1878, 1881, 1910, 1914, 1918, 1920, 1925, and others up to 1975.

The classic case study in end-times psychology is the 1843 "Great Disappointment" that unfolded after William Miller became "fully convinced that sometime between March 21st, 1843, and March 21st, 1844…Christ will come and bring all his saints with him." When March 21, 1844 came and went without note, the temporary great disappointment was followed by a recalcitrant recalculating of a new date, which was the "tenth day of the seventh month of the Jewish sacred year," October 22, 1844. When the new date passed without note, one disciple announced that "our fondest hopes and expectations were blasted, and such a spirit of weeping came over us as I never experienced before. We wept and wept until the day dawned." That disciple was Hiram Edson who, after concluding that Miller had misread the Book of Daniel, determined that the Sabbath should be observed on Saturday, the seventh and last day of the Jewish week, and he went on to become a leader of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church.

But religionists hold no monopoly on the apocalypse. There are also secular end of days, from Karl Marx's end of capitalism and Francis Fukuyama's end of history, to natural and man-made doomsdays brought about by overpopulation, pollution, nuclear winter, genetically engineered viruses, Y2K, solar flares, rogue planets, black holes, cosmic collisions, polar shifts, super volcanoes, resource depletion, runaway nanotechnology, and most notably, global warming. In his book Our Final Hour, the British Astronomer Royal Sir Martin Rees put our chances of surviving the 21st century at 50 percent. Last year Stephen Hawking famously warned humanity that contact with aliens could result in our enslavement or extinction.

In all of these apocalyptic prophecies—religious and secular—there is a sense of both fear and hope, and herein lies a clue to their appeal. For most true believers the end of the world is actually a transition to a new beginning and a better life to come. For religionists, God destroys Satan and sinners and resurrects the virtuous. For secularists, good triumphs over evil in myriad ways depending on one's doomsday preferences. Radical feminists have prophesized a day when patriarchy will collapse and men and women will live in egalitarian harmony. Marxists projected communism as the liberating climax of a six-stage evolutionary process that requires the collapse of capitalism. Liberal democrats proclaimed the end of history when the Cold War was won by democracy and liberty. And most recently, the Tea Party's messiah is John Galt, the hero of Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged, who leads a strike by the men of the mind, forcing civilization to collapse into anarchy, out of the ashes from which the heroes resurrect an "Atlantis" on earth. In the book's final apocalyptic scene the heroine Dagny Taggart turns to Galt and pronounces "It's the end." He corrects her: "It's the beginning."

Whatever the circumstance or setting, it plays out the same: destruction is followed by redemption. Why? What is the underlying psychology of the apocalypse? In my new book The Believing Brain (Times Books), to be published next week should the world continue its existence, I present my thesis that we form our beliefs for a variety of subjective, emotional, and psychological reasons in the context of environments created by family, friends, colleagues, and culture; after forming our beliefs we then defend, justify, and rationalize them with a host of intellectual reasons and rational explanations. Beliefs come first, explanations for beliefs follow. The brain is a belief engine. From sensory data flowing in through the senses the brain naturally begins to look for and find patterns, and then infuses those patterns with meaning. I call this first process patternicity, or the tendency to find meaningful patterns in both meaningful and meaningless data, and the second process I describe as agenticity, or the tendency to infuse patterns with meaning, intention, and agency. Once our brains connect the dots of our world into meaningful patterns of belief, we look for and find confirming evidence to support them and employ a host of cognitive biases that insure we are always right.

In this belief model, the apocalypse is a pattern of chronology based on our cognitive percepts of passing time from past to future, with a fleeting moment (about three seconds) of a present in between. Our brains are wired to denote patterns of time from beginning to end, and then infuse those patterns with agency and intention, be it God settling moral scores or nature knocking us off our pedestal of human hubris. As well as making things right, apocalyptic visions also help us make sense of an often seemingly senseless world. The literal meaning of apocalypse is "unveiling," or "revelation," from St. John the Divine's narrative in the book of Revelation to any number of the secular chronologies that fit the events of history into a larger cosmic design. How much easier it is to suffer the slings and arrows of life when you believe that it is all a part of a deeper, unfolding plan, whether determined by God or nature. We may feel like flotsam and jetsam on the vast rivers of history, but when the currents are directed toward a final destination it elevates the meaning of our place in it.

In the face of confusion and annihilation we need restitution and reassurance. We want to feel that no matter how chaotic, oppressive, or evil the world is, all will be made right in the end. The apocalypse as history's end is made acceptable with the belief that there will be a new beginning.

May 3, 2011

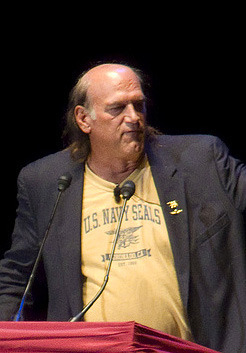

Jesse "The Body" Ventura versus Michael "The Mind" Shermer

Jesse Ventura (photo by Cory Barnes, used under CC BY-SA 2.0)

On Monday afternoon, April 11, I appeared on Southern California Public Radio KPCC's Patt Morrison show to briefly debate (dare I saw wrestle?) the former Navy Seal, Minnesota Governor, professional wrestler, television host, and author Jesse "The Body" Ventura, who was on a book tour swing through Los Angeles promoting his latest conspiracy fictions he believes are facts entitled The 63 Documents the Government Doesn't Want You To Read. (The figure of 63 was chosen, Jesse says, because that was the year JFK was assassinated.) Presented in breathtaking revelatory tones that within lies the equivalent of the Pentagon Papers, what the reader actually finds between the covers are documents obtained through standard Freedom of Information Act requests that can also be easily downloaded from the Internet.

Order the book from Amazon.com

No matter, with bigger-than-life Jesse Ventura at the conspiratorial helm everything is larger than it seems, especially when his unmistakable booming voice pronounces them as truths. I had only a few hours to read the book, but that turned out to be more than adequate since most of the documents are familiar to us conspiracy watchers and what little added commentary is provided to introduce them appears to be mostly written by Ventura's co-author Dick Russell, the pen behind the mouth for many of Jesse's books. (Since he is no longer wrestling perhaps he should change his moniker to Jesse "The Mouth" Ventura.)

Surprisingly, given his background in the military and government, Ventura seems surprised to learn that governments lie to their citizens. Shockingly true, yes, but just because politicians and their appointed cabinet assigns and their staffers sometimes lie (mostly in the interest of national security but occasionally to cover up their own incompetence and moral misdeeds), doesn't mean that every pronouncement made in the name of a government action is a lie. After all, as in the old logical chestnut—"This statement is untrue" (if it's true it's untrue and vice versa)—if everything is a lie then nothing is a lie. Likewise, I noted up front on the show, if everything is a conspiracy then nothing is a conspiracy.

Given the helter skelter nature of talk radio and Jesse's propensity to interrupt through his booming voice any dissenters from his POV, I tried to make just four points. Let's call them Conspiracy Skeptical Principles.

Conspiracy Skeptical Principle #1: There must be some means of discriminating between true and false conspiracy theories. Lincoln was assassinated by a conspiracy; JFK was not. The Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by a conspiracy of Serbian operatives that triggered the outbreak of the First World War; Princess Diana was not murdered by the Royal Family or any other secretive organization, but instead died by the most common form of death on a highway: speeding, drunk driving, and no seat belt.

Conspiracy Skeptical Principle #2: Cognitive Dissonance and the need to balance the size of the event with the size of the cause. Jesse Ventura said: "Do you mean to tell me that 19 guys with box cutters taking orders from a guy in a cave in Afghanistan brought down the most powerful nation on earth?" First of all, America is alive and well, thank you, even though Ventura has since moved to Mexico. But, yes, as a matter of fact, that is the only way such an event can happen: Sizable cohorts of operatives in prominent positions (Bush, Rumsfeld, Chaney, the CIA, the FBI, et al.) are too noticeable to get away with such a conspiracy. (By the way, 9/11 was a conspiracy: 19 members of Al Qaeda plotting to fly planes into buildings without telling us ahead of time constitutes a conspiracy.) It is the lone nuts living in the nooks and crannies of a free society (think Lee Harvey Oswald, John Hinkley, etc.) who become invisible by blending into the background scenery.

Order the Skeptic magazine 9/11 issue and read Phil Molé's take on the "9/11 Truth Movement" on Skeptic.com

Conspiracy Skeptical Principle #3: What else would have to be true if your conspiracy theory is true? Jesse proclaimed on the show that the Pentagon was hit by a missile. His proof? He interviewed a woman on his conspiracy TV show who said she worked inside the Pentagon and never saw a plane hit it. Well, first of all, earlier in the show when I brought up Jesse's conspiracy television series he discounted it, saying "that's pure entertainment." But now he wants to use an interview from that same show not as entertainment but as proof. As well, hardly anyone working in the Pentagon that day saw anything happen because they were inside the five-sided building and the plane only hit on one side, and even there, presumably (hopefully), people are actually working and not just sitting there staring out the window all day. But to the skeptical principle: As I said on the show, "If a missile hit the Pentagon, Jesse, that means that a plane did not hit it. What happened to the American Airlines plane?" Jesse's answer: "I don't know." Sorry Jesse, not good enough. It's not enough to poke holes at the government explanation for 9/11 (a form of negative evidence); you must also present positive evidence for your theory. In this case, tell us what happened to the plane that didn't hit the Pentagon because there are a lot of grieving families who would like to know what happened to their loved ones (as would several radar operators who tracked the plane from hijacking to suddenly disappearing off the screen in the same place as the Pentagon is located). Finally, I directed Jesse and our listeners to www.skeptic.com to view the photograph of the American Airlines plane debris on the lawn in front of the Pentagon, below. Are we to believe that the U.S. government timed the impact of a missile on the Pentagon with the hijackers who flew the plane into the Pentagon?

010911-N-6157F-001 Arlington, Va. (Sep. 11, 2001) — Wreckage from the hijacked American Airlines FLT 77 sits on the west lawn of the Pentagon minutes after terrorists crashed the aircraft into the southwest corner of the building. The Boeing 757 was bound for Los Angeles with 58 passengers and 6 crew. All aboard the aircraft were killed, along with 125 people in the Pentagon. (Photo by U.S. Navy Photo by Journalist 1st Class Mark D. Faram) (RELEASED)

Conspiracy Skeptical Principle #4: Your conspiracy theory must be more consistent than the accepted explanation. Jesse says that Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda did not orchestrate 9/11, and instead it was done by the Bush administration (or, he says, at least by Chaney and his covert operatives). As evidence, Jesse wants to know why Osama bin Laden has not been indicted for murder by the United States government. As well, he says, why was no one fired for not acting on the famous memos of the summer of 2001 that warned our government that Al Qaeda was financing operatives in America in flight training schools and that Osama bin Laden would strike on U.S. soil. Hold on there Jesse—first you say that Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda are innocent of this crime, and then you present evidence in the form of documents that the U.S. government was forewarned that Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda would attack us? Sorry sir, you can't have it both ways. You can't hold to two contradictory conspiracy theories at the same time and use evidence from each to support the other. (Well, you can, but that would be a splendid example of logic-tight compartments in your head keeping separate contradictory ideas.)

Finally, in frustration I presume, Jesse accused me of being a mouthpiece of the government, just parroting whatever my overlords command me to say to keep the truth hidden. That conspiracy theory happens to be true, except for the part about the mouthpiece, the government, the parrot, and the truth.

P.S. During my recent lecture tour swing through Wisconsin I was confronted at a restaurant by three 9/11 Truthers who were unable to attend my talk that night or even join the local skeptics group meeting that afternoon with me, and instead handed me a pile of literature and a DVD to watch touting the merits of the group known as Architects and Engineers for 9/11 Truth, who appear to hold fast to the belief that the WTC buildings were intentionally demolished by explosive devices AND that the hijackers (whoever they really were) somehow managed to fly the planes into the WTC buildings at precisely where the demolition experts planted the explosive devices—at the exact correct floors, at the exact angle at which the wings were tilted, because that is where the collapse of both buildings began. Check it out yourself below, along with our issue of Skeptic on 9/11 conspiracy theories, which was being read in Wisconsin by the little Wombat given to me by my hosts at the University of Wisconsin.

May 1, 2011

Extrasensory Pornception

PSI, OR THE PARANORMAL, denotes anomalous psychological effects that are currently unexplained by normal causes. Historically such phenomena eventually are either accounted for by normal means, or else they disappear under controlled conditions. But now renowned psychologist Daryl J. Bem claims experimental proof of precognition (conscious cognitive awareness) and premonition (affective apprehension) "of a future event that could not otherwise be anticipated through any known inferential process," as he wrote recently in "Feeling the Future" in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Bem sat subjects in front of a computer screen that displayed two curtains, behind one of which would appear a photograph that was neutral, negative or erotic. Through 36 trials the subjects were to preselect which screen they thought the image would appear behind, after which the computer randomly chose the window to project the image onto. When the images were neutral, the subjects did no better than 50–50. But when the images were erotic, the subjects preselected the correct screen 53.1 percent of the time, which Bem reports as statistically significant.

Bem calls this "retroactive influence"—erotic images ripple back from the future—or as comedian Stephen Colbert called it when he featured Bem on his show The Colbert Report, "extrasensory pornception."

For many reasons, I am skeptical. First, over the past century dozens of such studies proclaiming statistically significant results have turned out to be methodologically flawed, subject to experimenter bias and nonreproducible. This assessment by University of Amsterdam psychologist Eric-Jan Wagenmakers appeared along with Bem's study in the same journal.

Second, Bem's study is an example of negative evidence: if science cannot determine the causes of X through normal means, then X must be the result of paranormal causes. Ray Hyman, an emeritus professor of psychology at the University of Oregon and an expert on assessing paranormal research, calls this issue the "patchwork quilt problem" in which "anything can count as psi, but nothing can count against it." In essence, "if you can show that there is a significant effect and you can't find any normal means to explain it, then you can claim psi."

Third, paranormal effects, which are rarely allegedly detected at all, are always so subtle and fleeting as to be useless for anything practical, such as locating missing persons, gambling, investing, and so on.

Fourth, a small but consistent effect might be significant (for example, in gambling or investing), but according to Hyman, Bem's 3 percent above-chance effect in experiment 1 was not consistent across his nine experiments, which measured different effects under varying conditions.

Fifth, experimental inconsistencies plague such research. Hyman notes that in Bem's first experiment, the first 40 subjects were exposed to equal numbers of erotic, neutral and negative pictures. Then he changed the experiment midstream and, for the remaining subjects, just compared erotic images with an unspecified mix of all types of pictures. Plus, Bem's fifth experiment was conducted before his first, which raises the possibility that there might be a post hoc bias either in running the experiments or in reporting the results. Moreover, Bem notes that "most of the pictures" were selected from the International Affective Picture System, but he does not tell us which ones were not, why or why not, or what procedure he employed to classify images as erotic, neutral or negative. Hyman's list of flaws numbers in the dozens. "I've been a peer reviewer for more than 50 years," Hyman told me, "and I can't think of another reviewer who would have let this paper through peer review. They were irresponsible."

Perhaps they missed what psychologist James Alcock of York University in Toronto found in Bem's paper entitled "Writing the Empirical Journal Article" on his website, in which Bem instructs students: "Think of your data set as a jewel. Your task is to cut and polish it, to select the facets to highlight, and to craft the best setting for it. Many experienced authors write the results section first."

Bem has responded (www.dbem.ws), but I have a premonition his precognition was a postcognition.

April 19, 2011

The Immortalist

A Review of Transcendent Man: A Film About the Life and Ideas of Ray Kurzweil. Produced by Barry Ptolemy, Music by Philip Glass, inspired by the book The Singularity is Near by Ray Kurzweil. Digital release March 1, DVD release May 25.

Beware the prophet who proclaims the end of the world, the apocalypse, doomsday, judgment day, the second coming, the resurrection, or the Biggest Thing to Happen to Humanity ever will happen in the prophet's own lifetime. It is our natural inclination to assume that we are special and that our generation will witness the new dawn, but the Copernican Principle tells us that we are not special. Thus, the chances that even a science-based prophecy such as that proffered by the futurist, inventor, and scientistic visionary extraordinaire Ray Kurzweil—that by 2029 we will have the science and technology to live forever—is unlikely to be fulfilled.

Transcendent Man is Barry Ptolemy's beautifully crafted and artfully edited documentary film about Kurzweil and his quest to save humanity. If you enjoy contemplating the Big Questions in Life from a scientific perspective, you will love this film. Accompanied by the eerily haunting music of Philip Glass who, appropriately enough, also scored Errol Morris' film The Fog of War—about another bigger-than-life character who thought he could mold the world through data-driven decisions, Robert McNamara—Transcendent Man pulls viewers in through Kurzweil's visage of a future in which we merge with our machines and vastly extend our longevity and intelligence to the point where even death will be defeated. This point is what Kurzweil calls the "singularity" (inspired by the physics term denoting the infinitely dense point at the center of a black hole), and he arrives at the 2029 date by extrapolating curves based on what he calls the "law of accelerating returns." This is "Moore's Law" (the doubling of computing power every year) on steroids, applied to every conceivable area of science, technology and economics.

Ptolemy's portrayal of Kurzweil is unmistakably positive, but to his credit he includes several critics from both religion and science. From the former, a radio host named Chuck Missler, a born-again Christian who heads the Koinonia Institute ("dedicated to training and equipping the serious Christian to sojourn in today's world"), proclaims: "We have a scenario laid out that the world is heading for an Armageddon and you and I are going to be the generation that's alive that is going to see all this unfold." He seems to be saying that Kurzweil is right about the second coming, but wrong about what it is that is coming. (Of course, Missler's prognostication is the N+1 failed prophecy that began with Jesus himself, who told his followers (Mark 9:1): "Verily I say unto you, That there be some of them that stand here, which shall not taste of death, till they have seen the kingdom of God come with power.") Another religiously-based admonition comes from the Stanford University neuroscientist William Huribut, who self-identifies as a "practicing Christian" who believes in immortality, but not in the way Kurzweil envisions it. "Death is conquered spiritually," he pronounced.

On the science side of the ledger, Neil Gershenfeld, director of the Center for Bits and Atoms at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, sagely notes: "What Ray does consistently is to take a whole bunch of steps that everybody agrees on and take principles for extrapolating that everybody agrees on and show they lead to things that nobody agrees on." Likewise, the estimable futurist Kevin Kelly, whose 2010 book What Technology Wants paints a much more realistic portrait of what our futures may (or may not) hold, asks rhetorically "What happens in 40 years from now and Ray dies and doesn't have his father back? What does all this mean? Was he wrong? Well, he was right about some things. But in my observation the precursors of those technologies that would have to exist simply are not here. Ray's longing for this, his expectation, is heartwarming, but it isn't going to happen." Kelly agrees that Kurzweil's exponential growth curves are accurate but that the conclusions and especially the inspiration drawn from them are not. "He seems to have no doubts about it and in this sense I think he is a prophetic type figure who is completely sure and nothing can waiver his absolute certainty about this. So I would say he is a modern day prophet…that's wrong."

Transcendent Man is clearly meant to be an uplifting film celebrating all the ways science and technology have and are going to enrich our lives. I don't know if it is the music or the cinematography or the subject himself, but I found Transcendent Man to be a sad film about a genius who has been in agony since the premature death of his father at age 58. Fredric Kurzweil was a professional musician who Ray's mother says on camera was never around while his charge was growing up. Like father like son—Kurzweil's own workaholic tendencies in his creation of over a dozen companies starting when he was 17 meant he never really knew his father. As the film portrays the tormented inventor, Kurzweil's mission in life seems more focused on resurrecting his patriarch than rescuing humanity.

An especially lachrymose moment is when Kurzweil is rifling through his father's journals and documents in a storage room dedicated to preserving his memory until the day that all this "data" (including Ray's own fading memories) can be reconfigured into an A.I. simulacrum so that father and son can be reunited. Through heavy sighs and wistful looks Kurzweil comes off not as a proselytizer on a mission but as a man tormented. It is, in fact, the film's leitmotif. In one scene Kurzweil is shown wiping away a tear at his father's gravesite, in another he pauses over photographs and looks longingly at mementos, and in another cut at the beach Kurzweil recalls the day his father "uncharacteristically" phoned him just days before his death, as if he'd had a premonition. Although Kurzweil says he is optimistic and cheery about life, he can't seem to stop talking about death: "It's such a profoundly sad, lonely feeling that I really can't bear it," he admits. "So I go back to thinking about how I'm not going to die." One wonders how much of life he is missing by over thinking death, or how burdensome it must surely be to imbibe over 200 supplement tables a day and have your blood tested and cleansed every couple of months, all in an effort to reprogram the body's biochemistry.

There is something almost religious about Kurzweil's scientism, an observation he himself makes in the film, noting the similarities between his goals and that of the world's religions: "the idea of a profound transformation in the future, eternal life, bringing back the dead—but the fact that we're applying technology to achieve the goals that have been talked about in all human philosophies is not accidental because it does reflect the goal of humanity." Although the film never discloses Kurzweil's religious beliefs (he was raised by Jewish parents as a Unitarian Universalist), in a (presumably) unintentionally humorous moment that ends the film Kurzweil reflects on the God question and answers it himself: "Does God exist? I would say, 'Not yet.'" Cheeky.

April 5, 2011

The Woo of Creation: My evening with Deepak Chopra

On Thursday, March 31, Deepak Chopra and I squared off for a second time in person in a public venue, this time accompanied by the physicist Leonard Mlodinow on my side and Stuart Hameroff on his side (along with other panelists). The question on the table was this:

"Is there an Ultimate Reality?" and if yes, "Can it be accounted for by science such as mathematics, biology and physics?"

My answers: YES and YES

I explained that I am a Materialist and a Monist. I do not believe that there is a body and a soul, there is just a body. There is no brain and mind, just brain. The mind is just a word we use to describe what the brain does. I said, "you know I'm right" (which got a surprising laugh from the audience) because of the evidence from strokes, tumors, brain damage, senility, dementia, and Alzheimer's, all of which kill brain cells, and along with the loss of brain comes the loss of mind. I asked Deepak and Stuart where Aunt Millie's mind goes when her brain slowly disappears from the effects of Alzheimer's disease.

I noted that consciousness is just a word we use to describe our inner thoughts about the workings of the brain, and that our "soul" is just a pattern of information stored in our genes and our brains. Consciousness is just an emergent property of integrated brain modules and patterned firing of neural networks.

By contrast, I believe that Deepak's use of the word "consciousness" is very anthropocentric, once again returning humans to a central place in the cosmos as the "observers" who, in quantum mechanics, brings things into existence. If Deepak is right then the moon doesn't exist unless it is observed, and yet, quoting that great scientist Bill O'Reilly, "times come in, tides go out—never a missed communication—and they would do so whether or not humans, or any other conscious (or unconscious) being existed.

In fact, I said, Deepak's quantum consciousness is not holistic but reductionistic in the extreme. We don't need to go down that far. Quantum mechanics is not needed to explain brain functions: the neuron is the individual unit of thought, the "atom" of mind. I then worked in a little joke I wrote earlier in the day:

Quantum mechanics is spooky and weird.

Consciousness is spooky and weird.

So what? Charlie Sheen is spooky and weird, but we don't need quantum mechanics to explain his behavior. His "tiger blood" theory works just fine.

Haha.

In Deepak's worldview, everything is conscious, which means that there is no way to distinguish between consciousness and unconsciousness, which is how I often feel when I listen to Deepak.

Thought Experiment:

If humans went extinct instead of Neanderthals, how does that effect the universe?

What if the Earth were suddenly demolished by a rogue planet (as in 2012)? Would that mean the end of the universe because observers would disappear?

Are whales, dolphins, gorillas and chimps conscious and therefore integral to the universe?

What can it possibly mean to say that the universe is conscious? If you will pardon the nerd science pun, that is such a vacuous concept!

Before the debate Deepak asked me to read a paper by himself and Menas Kafatos and Rudolph Tanzi published in the Journal of Cosmology, entitled: "How Consciousness Becomes the Physical Universe." Deepak asked me to comment on it, which I did in the second half of the debate. I noted that given the prominence of "consciousness" to the central theme of the paper that one might expect it to be defined with semantic precision. Nope. Here is what the authors write:

"We will sidestep any precise definition of consciousness, limiting ourselves for now to willful actions on the part of the observer."

What can it possibly mean for the universe to be conscious in the sense of having willful actions? The universe behaves with willful action? The universe is an observer? As well, quantum mechanics only requires an observation of any kind: an electron microscope will do. Is an electron microscope willful? Does an electron microscope take action? The authors of this paper write:

Werner Heisenberg concluded that the atom "has no immediate and direct physical properties at all." If the universe's basic building block isn't physical, then the same must hold true in some way for the whole. The universe was doing a vanishing act in Heisenberg's day, and it certainly hasn't become more solid since. And Heisenberg again: "The atoms or elementary particles themselves … form a world of potentialities or possibilities rather than one of things or facts."

No, sorry, these are different levels of analysis. To prove it I challenge Deepak to climb to the top of this building and jump off and see if the ground is a potentiality or a thing! They also write:

Heisenberg: "What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning." Reality, it seems, shifts according to the observer's conscious intent.

Once again, NO! This would imply that anyone's method of questioning is just as valid as anyone else's, which would mean that the way astrologers question the universe is just as valid as that of astronomers. I concluded by saying that if you want to get a spacecraft to Mars the questions that astronomers ask are absolutely objectively really better than those of astrologers. Q.E.D.!

In Deepak's rebuttal, in discussing quantum mechanics, he actually used the phrase "the womb of creation." Nice. It's that sort of precise language that makes people all gushy and mushy about science. I pressed him for a definition of consciousness, which he gave me as "consciousness if the ground of existence." I replied that this sounded tautological to me: since reality needs consciousness to come into existence, this means that reality = consciousness = existence; or existence = existence. A is A. Very Aristotelian. But what does that really tell us?

In the end I pressed both Deepak and Stuart Hameroff for an answer as to where Aunt Millie's mind goes during the ravages of Alzheimer's disease. Stuart's answer was so rapid fire and jargon laden (something about the collapse of the wave function inside the microtubules in the neurons inside Aunt Millie's brain) that I couldn't quite get an answer, so Deepak clarified it for me later: Aunt Millie's mind is in the matrix. Okay, I asked, how does poor Aunt Millie access the matrix. "We're working on that," was the reply. Okay, fine, and if our memories really are stored somewhere outside of our brains, then that would indeed be one of the greatest discoveries ever made in the history of science: Nobel worthy. But, until that is proven, I remain … skeptical.

Post Script

I am often asked if I believe that Deepak believes what he says, with an underlying assumption behind the question that Deepak is knowingly selling snake oil and doesn't really believe his public patter. Having gotten to know Deepak over the years I can assure you that he absolutely positively believes what he says, and that while he may make a lot of money in the process of writing books, giving lectures, hosting radio and television shows, and running his various business enterprises (but, hey, that's not exactly something anathema in America), this fact is quite orthogonal to his deeper mission in life: to shift the Western worldview Eastward.

I had never met Stuart Hameroff before, but I liked him as well, sharing a beer after the debate while watching a Laker game and schmoozing about science. Although I do not accept his theory of consciousness (most neuroscientists are skeptical as well), it would be fun to engage him again in a spirited debate over the brain and the mind.

Michael Shermer's Blog

- Michael Shermer's profile

- 1155 followers