Michael Shermer's Blog, page 14

April 10, 2012

Are you an Atheist or Agnostic?

Recently my friend and colleague in science and skepticism Neil deGrasse Tyson, issued a public statement via BigThink.com in which he stated that he dislikes labels because they carry with them all the baggage that the person thinks they already know about that particular label, and thus he prefers no label at all when it comes to the god question and simply calls himself an agnostic.

The Believing Brain

by Michael Shermer

In this book, I present my theory on how beliefs are born, formed, nourished, reinforced, challenged, changed, and extinguished. Sam Harris calls The Believing Brain "a wonderfully lucid, accessible, and wide-ranging account of the boundary between justified and unjustified belief." Leonard Mlodinow calls it "a tour de force integrating neuroscience and the social sciences."

Order the autographed hardcover

Order the unabridged audio CD

Order the Kindle edition

Order the iBook edition

Listen to the Prologue for free

I have already written about this many times over the decades, and my 1999 book How We Believe outlines in detail why I too hate labels. In fact, in my later book, The Mind of the Market, I explained why I also do not like the label "libertarian" because people automatically think this means believing something that I very likely do not believe (e.g., that humans are by nature purely selfish, that we have no moral obligation to help others in need, that greed is the only motive that counts in business, and that Ayn Rand was actually the Messiah), and instead I prefer to go issue by issue. Nevertheless, the label "libertarian" and "atheist" stick, and as I explained in my latest book, The Believing Brain, I've largely given up the anti-label struggle and just call myself by these labels. In effect, what I once thought of as intellectual laziness on the part of my interlocuters who did not seem to want to bother to actually read my clarifications and what, exactly, I do believe about this or that issue, I now see as the normal process of cognitive shortcutting. Time is short and information is vast. Most of the time our brains just pigeonhole information into categories we already know in order to move on to the next problem to solve, such as why not one Mexican restaurant band I have ever asked seems to know one of the greatest Spanish pieces ever produced: Malagueña. It's a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside a tortilla.

Still, it is worth thinking about what the difference is between atheist and agnostic. According to the Oxford English Dictionary: Theism is "belief in a deity, or deities" and "belief in one God as creator and supreme ruler of the universe." Atheism is "Disbelief in, or denial of, the existence of a God." Agnosticism is "unknowing, unknown, unknowable."

Agnosticism was coined in 1869 by Thomas Henry Huxley to describe his own beliefs:

When I reached intellectual maturity and began to ask myself whether I was an atheist, a theist, or a pantheist…I found that the more I learned and reflected, the less ready was the answer. They [believers] were quite sure they had attained a certain 'gnosis,'—had, more or less successfully, solved the problem of existence; while I was quite sure I had not, and had a pretty strong conviction that the problem was insoluble.

Of course, no one is agnostic behaviorally. When we act in the world, we act as if there is a God or as if there is no God, so by default we must make a choice, if not intellectually then at least behaviorally. To this extent, I assume that there is no God and I live my life accordingly, which makes me an atheist. In other words, agnosticism is an intellectual position, a statement about the existence or nonexistence of the deity and our ability to know it with certainty, whereas atheism is a behavioral position, a statement about what assumptions we make about the world in which we behave.

When most people employ the word "atheist," they are thinking of strong atheism that asserts that God does not exist, which is not a tenable position (you cannot prove a negative). Weak atheism simply withholds belief in God for lack of evidence, which we all practice for nearly all the gods ever believed in history. As well, people tend to equate atheism with certain political, economic, and social ideologies, such as communism, socialism, extreme liberalism, moral relativism, and the like. Since I am a fiscal conservative, civil libertarian, and most definitely not a moral relativist, this association does not fit me. The word "atheist" is fine, but since I publish a magazine called Skeptic and write a monthly column for Scientific American called "Skeptic," I prefer that as my label. A skeptic simply does not believe a knowledge claim until sufficient evidence is presented to reject the null hypothesis (that a knowledge claim is not true until proven otherwise). I do not know that there is no God, but I do not believe in God, and have good reasons to think that the concept of God is socially and psychologically constructed.

The burden of proof is on believers to prove God's existence—not on nonbelievers to disprove it—and to date theists have failed to prove God's existence, at least by the high evidentiary standards of science and reason. So we return again to the nature of belief and the origin of belief in God. In The Believing Brain I present extensive evidence to demonstrate quite positively that humans created gods and not vice versa.

April 1, 2012

Climbing Mount Immortality

may be a major driver of civilization

IMAGINE YOURSELF DEAD. What picture comes to mind? Your funeral with a casket surrounded by family and friends? Complete darkness and void? In either case, you are still conscious and observing the scene. In reality, you can no more envision what it is like to be dead than you can visualize yourself before you were born. Death is cognitively nonexistent, and yet we know it is real because every one of the 100 billion people who lived before us is gone. As Christopher Hitchens told an audience I was in shortly before his death, "I'm dying, but so are all of you." Reality check.

In his book Immortality: The Quest to Live Forever and How It Drives Civilization (Crown, 2012), British philosopher and Financial Times essayist Stephen Cave calls this the Mortality Paradox. "Death therefore presents itself as both inevitable and impossible," Cave suggests. We see it all around us, and yet "it involves the end of consciousness, and we cannot consciously simulate what it is like to not be conscious."

The attempt to resolve the paradox has led to four immortality narratives:

Staying alive: "Like all living systems, we strive to avoid death. The dream of doing so forever—physically, in this world—is the most basic of immortality narratives."

Resurrection: "The belief that, although we must physically die, nonetheless we can physically rise again with the bodies we knew in life."

Soul: The "dream of surviving as some kind of spiritual entity."

Legacy: "More indirect ways of extending ourselves into the future" such as glory, reputation, historical impact or children.

All four fail to deliver everlasting life. Science is nowhere near reengineering the body to stay alive beyond 120 years. Both religious and scientific forms of resurrecting your body succumb to the Transformation Problem (how could you be reassembled just as you were and yet this time be invulnerable to disease and death?) and the Duplication Problem (how would duplicates be different from twins?). "Even if DigiGod made a perfect copy of you at the end of time," Case conjectures, "it would be exactly that: a copy, an entirely new person who just happened to have the same memories and beliefs as you." The soul hypothesis has been slain by neuroscience showing that the mind (consciousness, memory and personality patterns representing "you") cannot exist without the brain. When the brain dies of injury, stroke, dementia or Alzheimer's, the mind dies with it. No brain, no mind; no body, no soul.

That leaves the legacy narrative, of which Woody Allen quipped: "I don't want to achieve immortality through my work; I want to achieve it by not dying." Nevertheless, Cave argues that legacy is the driving force behind creative works of art, music, literature, science, culture, architecture and other artifacts of civilization. How? Because of something called Terror Management Theory. Awareness of one's mortality focuses the mind to create and produce to avoid the terror that comes from confronting the mortality paradox that would otherwise, in the words of the theory's proponents—psychologists Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg and Tom Pyszczynski—reduce us to "twitching blobs of biological protoplasm completely perfused with anxiety and unable to effectively respond to the demands of their immediate surroundings."

Maybe, but human behavior is multivariate in causality, and fear of death is only one of many drivers of creativity and productivity. A baser evolutionary driver is sexual selection, in which organisms from bowerbirds to brainy bohemians engage in the creative production of magnificent works with the express purpose of attracting mates—from big blue bowerbird nests to big-brained orchestral music, epic poems, stirring literature and even scientific discoveries. As well argued by evolutionary psychologist Geoffrey Miller in The Mating Mind (Anchor, 2001), those that do so most effectively leave behind more offspring and thus pass on their creative genes to future generations. As Hitchens once told me, mastering the pen and the podium means never having to dine or sleep alone.

Given the improbability of the first three immortality narratives, making a difference in the world in the form of a legacy that changes lives for the better is the highest we can climb up Mount Immortality, but on a clear day you can see forever.

March 27, 2012

Reason Rally Rocks

March 24, 2012 marked the largest gathering of skeptics, atheists, humanists, nonbelievers, and "nones" (those who tick the "no religion" box on surveys) of all stripes on the Mall in Washington, D.C., across from the original Smithsonian museum. Crowd estimates vary from 15,000 to 25,000. However many it was, it was one rockin' huge crowd that voiced its support for reason, science, and skepticism louder than any I have ever heard. Anywhere. Any time. Any place. It started raining just as the festivities gathered steam late morning, but the weather seemed to have no effect whatsoever on the enthusiasm and energy of the crowd…or the speakers and performers. The organizer and host David Silverman and his posse of tireless staff and volunteers pulled it off without a hitch. Organizing big events can be an organizational nightmare, but they did it, marking what I hope is the first of many consciousness raising events in the civil rights movement for equal treatment for us nonbelievers and skeptics.

James Randi and I arrived well before our scheduled talk time and mingled among the crowds, swamped with well-wishers and camera-hounds and feeling the love from so many people that makes fighting the good fight for science and reason well worth it when you know there are people out there who care. Hanging out behind the stage and in the wings was an especially nice treat for me as I got to watch the speakers and performers and the audience together. Someone snapped this pic:

I think I was watching Tim Minchin, whom I have never met or seen perform live. It was clear from the start that he was a major headliner as the audience exploded in energy for him, cajoling him to remove his boots and perform barefoot, one of his trademark features, along with distinct eyeliner highlighting his radiant blue eyes (he says he uses make-up in order to highlight facial expressions for audiences because his hands are usually both busy on the keyboard). Here we are hanging out after his remarkable performance. He was brilliant, funny, witty, insightful, clever, and most of all inspirational. Minchin is a genius.

[image error]

No less a showman in humor and poignancy was Mr. MythBuster Adam Savage, who quickly moved off his scripted comments to do stand-up commentary on why science is the coolest thing one can possibly do. Even though Adam said "I'm not a scientist, but I play one on TV," I disagree. I think the MythBusters are doing science, at least provisionally in testing hypotheses by running experiments over and over and over until they get some result, often not the one they were expecting. The fact that they have fun doing it, and usually blow up the experiment at the end, should not distract us from the fact that the core principle behind MythBusters is testing hypotheses, which is the core principle behind science. Adam was absolutely loved by the crowd. Here we are back stage after his talk.

[image error]

One observation: there were rumors that the Westboro Baptist Church protestors were going to be there with their now-infamous signs declaring "God Hates Fags", and in anticipation of this people decided to fight hatred and bigotry with humor and wit, pace signs that read "God Hates Figs" and this one (right) plastered on bags carried around: "God Hates Bags."

I had 5 minutes to speak. It doesn't sound like much, but consider the fact that the greatest speech ever given in American history, Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I have a Dream" speech, was only 17 minutes long, and most of his other famous speeches, such as his "How Long, Not Long" speech, were even shorter. I began my talk by inveigling the crowd to, on the count of three, yell out "Skeptics Rule," then "Science Rules" then "Reason Rules." I couldn't resist filming it with my iPhone camera. Here it is, the loudest cheer I've ever heard for skeptics, science, and reason.

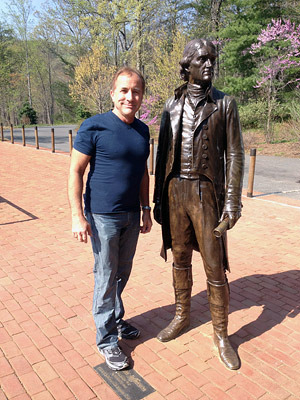

Here I am with my hero, TJ.

I veered away from my written speech here and there depending on the response from the crowd, and I added this line, which was picked up by the press and published in many places:

"America was no founded on God and religion. America was founded on reason."

I was especially motivated to make that comment because the day before I visited Thomas Jefferson's home, Monticello, which is a monument to reason. In point of fact, the Declaration of Independence is a monument to reason, along with the country it created.

March 1, 2012

Opting Out of Overoptimism

can be harmful

ARE YOU BETTER THAN AVERAGE AS A DRIVER? I know I am. I'll bet 90 percent of you think you are, too, because this is the well-documented phenomenon known as the above-average effect, part of the psychology of optimism.

According to psychologist Daniel Kahneman, in his 2011 book Thinking, Fast and Slow, "people tend to be overly optimistic about their relative standing on any activity in which they do moderately well." But optimism can slide dangerously into overoptimism. Research shows that chief financial officers, for example, "were grossly overconfident about their ability to forecast the market" when tested by Duke University professors who collected 11,600 CFO forecasts and matched them to market outcomes and found a correlation of less than zero! Such overconfidence can be costly. "The study of CFOs showed that those who were most confident and optimistic about the S&P index were also overconfident and optimistic about the prospects of their own firm, which went on to take more risk than others," Kahneman notes.

Isn't optimistic risk taking integral to building a successful business? Yes, to a point. "One of the benefits of an optimistic temperament is that it encourages persistence in the face of obstacles," Kahneman explains. But "pervasive optimistic bias" can be detrimental: "Most of us view the world as more benign than it really is, our own attributes as more favorable than they truly are, and the goals we adopt as more achievable than they are likely to be." For example, only 35 percent of small businesses survive in the U.S. When surveyed, however, 81 percent of entrepreneurs assessed their odds of success at 70 percent, and 33 percent of them went so far as to put their chances at 100 percent. So what? In a Canadian study Kahneman cites, 47 percent of inventors participating in the Inventor's Assistance Program, in which they paid for objective evaluations of their invention on 37 criteria, "continued development efforts even after being told that their project was hopeless, and on average these persistent (or obstinate) individuals doubled their initial losses before giving up." Failure may not be an option in the mind of an entrepreneur, but it is all too frequent in reality. High-risk-taking entrepreneurs override such loss aversion, a phenomenon most of us succumb to in which losses hurt twice as much as gains feel good that we developed in our evolutionary environment of scarcity and uncertainty.

This loss-aversion override by those with pervasive optimistic bias seems to work because of what I call biographical selection bias: the few entrepreneurs who succeed spectacularly have biographies (and autobiographies), whereas the many who fail do not.

Think Steve Jobs, whose pervasive optimistic bias was channeled through something a co-worker called Jobs's "reality distortion field." According to his biographer Walter Isaacson, "at the root of the reality distortion was Jobs's belief that the rules didn't apply to him…. He had the sense that he was special, a chosen one, an enlightened one." Jobs's optimism morphed into a reality-distorting will to power over rules that applied only to others and was reflected in numerous ways: legal (parking in handicapped spaces, driving without a license plate), moral (accusing Microsoft of ripping off Apple when both took from Xerox the idea of the mouse and the graphical user interface), personal (refusing to acknowledge his daughter Lisa even after an irrefutable paternity test), and practical (besting resource-heavy giant IBM in the computer market).

There was one reality Jobs's distortion field optimism could not completely bend to his will: cancer. After he was diagnosed with a treatable form of pancreatic cancer, Jobs initially refused surgery. "I really didn't want them to open up my body, so I tried to see if a few other things would work," he admitted to Isaacson. Those other things included consuming large quantities of carrot and fruit juices, bowel cleansings, hydrotherapy, acupuncture and herbal remedies, a vegan diet, and, Isaacson says, "a few other treatments he found on the Internet or by consulting people around the country, including a psychic." They didn't work. Out of this heroic tragedy a lesson emerges: reality must take precedence over willful optimism. Nature cannot be distorted.

February 28, 2012

Teaching Allah and Xenu in Indiana

Last month, the Indiana State Senate approved a bill that would allow public school science teachers to include religious explanations for the origin of life in their classes. If Senate Bill 89 is approved by the state's House its co-sponsor, Speaker of the House Dennis Kruse, hopes that this will open the door for the teaching of "creation-science" as a challenge to the theory of evolution, which he characterized as a "Johnny-come-lately" theory compared to the millennia-old creation story in Genesis: "I believe in creation and I believe it deserves to be taught in our public schools." In this bill Kruse is challenging the U.S. Supreme Court's 1987 decision in Edwards v. Aguillard that the mandatory teaching of a bible-based creation story in Louisiana public schools was violative of the first amendment and therefore unconstitutional (by a vote of 7-2, with Rehnquist and Scalia dissenting). "This is a different Supreme Court," Kruse defiantly said in an interview. "This Supreme Court could rule differently."

The language of the bill, however, was expanded by the Indiana State Senate Minority Leader Vi Simpson, a democrat, and includes the possibility of teaching the creation stories of religions other than Christianity. "The bill was originally talking about 'Creationist Science,' and I thought that was a bit of an oxymoron," Simpson told the Village Voice. "I wanted to draft an amendment that would do two things. First, it would remove it from the science realm. And second, school boards and the state of Indiana should not be in the business of promoting one religion over another." The bill now includes the following proviso: "The governing body of a school corporation may offer instruction on various theories of the origin of life. The curriculum for the course must include theories from multiple religions, which may include, but is not limited to, Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Scientology."

Scientology? Yes, Scientology has an origin story. Here it is. Imagine this account being taught in public school science classes in America: Around 75 million years ago Xenu, the ruler of a Galactic Confederation of 76 planets, transported billions of his people in spaceships to a planet named Teegeeack (Earth). There they were placed near volcanoes and killed by exploding hydrogen bombs, after which their souls, or "thetans," remained to inhabit the bodies of future earthlings, causing humans today great spiritual harm and unhappiness that may be remedied through psychological techniques involving a process called auditing and a device called an E-meter. This creation myth, formerly privy only to members who had achieved Operating Thetan Level III (OT III) through auditing, is now well known via the Internet and a widely-viewed 2005 episode of the animated sitcom television series South Park.

The absurdity of teaching religious origin stories in a science class could not be more poignant, but if there is any remaining doubt imagine the teaching of Islam and Allah in American public schools. There are, in fact, not multiple origin stories. There are only two: science-based and everything else. And legal precedence dictates that it is both inappropriate and illegal to force science teachers to teach non-science-based origin stories in science classes. Even before the U.S. Supreme Court voted against the teaching of creation-science in 1987, in 1981 the constitutionality of Arkansas Act 590, which required equal time in public school science classes for "creation-science" and "evolution-science," was ruled illegal by the federal judge William R. Overton on the grounds that creation-science conveys "an inescapable religiosity." Overton noted that the creationists employed a "two model approach" in a "contrived dualism" that "assumes only two explanations for the origins of life and existence of man, plants and animals: It was either the work of a creator or it was not." In this either-or paradigm, the creationists claim that any evidence "which fails to support the theory of evolution is necessarily scientific evidence in support of creationism." Overton slapped down this tactic: "evolution does not presuppose the absence of a creator or God and the plain inference conveyed by Section 4 [of Act 590] is erroneous." Judge Overton's opinion on why creation-science isn't science, and by extension what constitutes science, was so poignant that it was republished in the prestigious journal Science:

It is guided by natural law.

It has to be explanatory by reference to natural law.

It is testable against the empirical world.

Its conclusions are tentative.

It is falsifiable.

Overton concluded: "Creation science as described in Section 4(a) fails to meet these essential characteristics," adding the "obvious implication" that "knowledge does not require the imprimatur of legislation in order to become science."

By extension, the lesson to be gleaned from this latest legal battle in Indiana is that knowledge that requires the imprimatur of legislation is not science. QED.

February 14, 2012

The Natural & the Supernatural: Alfred Russel Wallace and the Nature of Science

A couple weeks ago, I participated in an online debate at Evolution News & Views with Center for Science & Culture fellow Michael Flannery on the question: "If he were alive today, would evolutionary theory's co-discoverer, Alfred Russel Wallace, be an intelligent design advocate?" Before reading this week's post, you can review my opening statement in my previous Skepticblog and Flannery's reply. The following is my response. A link to Flannery's final reply can be found near the end of this page.

Michael Flannery's assessment of Alfred Russel Wallace as a prescient scientist who anticipated modern Intelligent Design theory is premised on the belief that modern evolutionary biologists have failed to explain the myriad abilities of the human mind that Wallace outlined in his day as unanswered and—in his hyperselectionist formulation of evolutionary theory—unanswerable. In point of fact there are several testable hypotheses formulated by scientists—evolutionary psychologists in particular—that make the case that all aspects of the human mind are explicable by evolutionary theory. Flannery mentions just one—Steven Pinker's hypothesis that cognitive niches in the evolutionary environment of our Paleolithic hominid ancestors gave rise to abstract reasoning and metaphorical thinking that enabled future humans to navigate complex social and cognitive environments found in the modern world. In his PNAS paper Pinker outlines two processes at work: "One is that intelligence is an adaptation to a knowledge-using, socially interdependent lifestyle, the 'cognitive niche'." And: "The second hypothesis is that humans possess an ability of metaphorical abstraction, which allows them to coopt faculties that originally evolved for physical problem-solving and social coordination, apply them to abstract subject matter, and combine them productively." Together, Pinker concludes: "These abilities can help explain the emergence of abstract cognition without supernatural or exotic evolutionary forces and are in principle testable by analyses of statistical signs of selection in the human genome." Pinker then outlines a number of ways in which the cognitive niche hypothesis has been and can continue to be tested.

In point of fact, Darwin himself addressed this larger problem of "pre-adaptation": Since evolution is not prescient or goal directed—natural selection operates in the here-and-now and cannot anticipate what future organisms are going to need to survive in an ever-changing environment—how did certain modern useful features come to be in an ancestral environment different from our own? In Darwin's time this was called the "problem of incipient stages." Fully-formed wings are obviously an excellent adaptation for flight that provide all sorts of advantages for animals who have them; but of what use is half a wing? For Darwinian gradualism to work, each successive stage of wing development would need to be functional, but stumpy little partial wings are not aerodynamically capable of flight. Darwin answered his critics thusly:

Although an organ may not have been originally formed for some special purpose, if it now serves for this end we are justified in saying that it is specially contrived for it. On the same principle, if a man were to make a machine for some special purpose, but were to use old wheels, springs, and pulleys, only slightly altered, the whole machine, with all its parts, might be said to be specially contrived for that purpose. Thus throughout nature almost every part of each living being has probably served, in a slightly modified condition, for diverse purposes, and has acted in the living machinery of many ancient and distinct specific forms.1

Today this solution is called exaptation, in which a feature that originally evolved for one purpose is co-opted for a different purpose.2 The incipient stages in wing evolution had uses other than for aerodynamic flight—half wings were not poorly developed wings but well-developed something elses—perhaps thermoregulating devices. The first feathers in the fossil record, for example, are hairlike and resemble the insulating down of modern bird chicks.3 Since modern birds probably descended from bi-pedal therapod dinosaurs, wings with feathers could have been employed for regulating heat—holding them close to the body retains heat, stretching them out releases heat.4

So one testable hypothesis about the various aspects of the mind that so troubled Wallace is that cognitive abilities we exhibit today were employed for different purposes in our ancestral environment. In other words, they are exaptations, coopted for different uses today than that for which they originally evolved. But even if these hypotheses fail the tests new hypotheses will take their place to be empirically verified, rejected, or refined with additional data from the natural world. This is how science operates—the search for natural explanations for natural phenomena.

By contrast, Intelligent Design theorists offer no testable hypotheses at all, no natural explanations for natural phenomena. Instead, their answer to the mysteries of the mind is the same as that of all other mysteries of the universe: God did it. Although their narratives are gussied up in jargon-laden terms such as "irreducible complexity," "specified complexity," "complex specified information," "directed intelligence," "guided design," and of course "intelligent design"—these are not causal explanations. They are just linguistic fillers for "God did it" explanations. It is nothing more than the old "God of the gap" rubric: wherever creationists find what they perceive to be a gap in scientific knowledge, this must be where God intervened into the natural world. If they want to do science, however, they must provide testable hypothesis about how they think God (or the Intelligent Designer—ID) did it. What forces did ID use to bring about wings, eyes, and brains? Did ID intervene into the natural world at the level of species or genus? Did ID intervene at the Cambrian explosion or before (or after)? Did ID create the first cells and pack into their DNA the potential for future wings, eyes, and brains? Or did ID have to intervene periodically throughout the past billion years to build bodies one part at a time? And more to the point here, did ID layer on cortical neurons atop older naturally evolved brain structures to enable certain primates to reason more abstractly than other primates?

The reason scientists do not take seriously the claims of Intelligent Design theorists today is the same reason scientists did not take seriously Wallace's speculations about an "overarching intelligence" that guided evolution. As I noted previously, Wallace's hyperselectionism and hyperadaptationism blinded him to the possibilities offered in a multi-tiered evolutionary model where the concept of exaptation expands our thinking about how certain features might have evolved for reasons different from what they are used for today. As Wallace's biographer it is my opinion that he was driven as much by his overarching scientism of which his theory of evolution as pure adaptationism was a part, and that even his spiritualism was subsumed in his scientistic worldview.5

Read Flannery's final reply in this debate.

References

Darwin, Charles. 1862. On the Various Contrivances by Which British and Foreign Orchids Are Fertilized by Insects, and on the Good Effects of Intercrossing . London: John Murray. p. 348.

Gould, Stephen Jay and Elizabeth Vrba. 1982. "Exaptation: A Missing Term in the Science of Form." Paleobiology, 8, pp. 4–15.

Prum, R. O. and A. H. Brush. 2003. "Which Came First, the Feather or the Bird: A Long-Cherished View of How and Why Feathers Evolved Has Now Been Overturned." Scientific American, March, pp. 84–93.

Padian, Kevin and L. M. Chiappe. 1998. "The Origin of Birds and Their Flight." Scientific American, February, pp. 38–47.

Shermer, Michael. 2002. In Darwin's Shadow: The Life and Science of Alfred Russel Wallace . New York: Oxford University Press.

February 1, 2012

Lies We Tell Ourselves

In Andrew Lloyd Webber's 1970 rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar, a skeptical Judas Iscariot questions with faux innocence ("Don't you get me wrong/I only want to know") the messiah's deific nature: "Jesus Christ Superstar/Do you think you're what they say you are?"

Although I am skeptical of Jesus' divine parentage, I believe he would have answered Judas's query in the affrmative. Why? Because of what the legendary evolutionary theorist Robert Trivers calls "the logic of deceit and self-deception" in his new book The Folly of Fools (Basic Books, 2011). Here's how it works: A selfish-gene model of evolution dictates that we should maximize our reproductive success through cunning and deceit. Yet the dynamics of game theory shows that if you are aware that other contestants in the game will also be employing similar strategies, it behooves you to feign transparency and honesty and lure them into complacency before you defect and grab the spoils. But if they are like you in anticipating such a shift in strategy, they might pull the same trick, which means you must be keenly sensitive to their deceptions and they of yours. Thus, we evolved the capacity for deception detection, which led to an arms race between deception and deception detection.

Deception gains a slight edge over deception detection when the interactions are few in number and among strangers. But if you spend enough time with your interlocutors, they may leak their true intent through behavioral tells. As Trivers notes, "When interactions are anonymous or infrequent, behavioral cues cannot be read against a background of known behavior, so more general attributes of lying must be used." He identifies three:

Nervousness. "Because of the negative consequences of being detected, including being aggressed against … people are expected to be more nervous when lying."

Control. "In response to concern over appearing nervous … people may exert control, trying to suppress behavior, with possible detectable side effects such as … a planned and rehearsed impression."

Cognitive load. "Lying can be cognitively demanding. You must suppress the truth and construct a falsehood that is plausible on its face and … you must tell it in a convincing way and you must remember the story."

Cognitive load appears to play the biggest role. "Absent wellrehearsed lies, people who are lying have to think too hard, and this causes several effects," including overcontrol that leads to blinking and fidgeting less and using fewer hand gestures, longer pauses and higher-pitched voices. As Abraham Lincoln well advised, "You can fool some of the people all of the time and all of the people some of the time, but you cannot fool all of the people all of the time." Unless self-deception is involved. If you believe the lie, you are less likely to give off the normal cues of lying that others might perceive: deception and deception detection create self-deception.

Trivers's theory adds an evolutionary explanation to my own operant conditioning model to explain why psychics, mediums, cult leaders, and the like probably start off aware that a modicum of deception is involved in their craft (justified in the name of a higher cause). But as their followers positively reinforce their message, they come to believe their shtick ("maybe I really can read minds, tell the future, save humanity"). Trivers misses an opportunity to put a more positive spin on self-deception when it comes to the evolution of morality, however. As I argued in my 2004 book The Science of Good and Evil (Times Books), true morality evolved as a function of the fact that it is not enough to fake being a good person, because in our ancestral environments of small bands of hunter-gatherers in which everyone was either related to one another or knew one another intimately, faux morality would be unmasked. You actually have to be a good person by believing it yourself and acting accordingly.

By employing the logic of deception and self-deception, we can build a bottom-up theory for the evolution of emotions that control behavior judged good or evil by our fellow primates. In this understanding lies the foundation of a secular civil society.

January 31, 2012

Alfred Russel Wallace was a Hyper-Evolutionist, not an Intelligent Design Creationist

The double dangerous game of Whiggish What-if? history is on the table in this debate that inexorably invokes hindsight bias, along the lines of "Was Thomas Jefferson a racist because he had slaves?" Adjudicating historical belief and behavior with modern judicial scales is a fool's errand that carries but one virtue—enlightenment of the past for correcting current misunderstandings. Thus I shall endeavor to enlighten modern thinkers on the perils of misjudging Alfred Russel Wallace as an Intelligent Design creationist, and at the same time reveal the fundamental flaw in both his evolutionary theory and that of this latest incarnation of creationism.

Wallace's scientific heresy was first delivered in the April, 1869 issue of The Quarterly Review, in which he outlined what he saw as the failure of natural selection to explain the enlarged human brain (compared to apes), as well as the organs of speech, the hand, and the external form of the body:

In the brain of the lowest savages and, as far as we know, of the prehistoric races, we have an organ…little inferior in size and complexity to that of the highest types…. But the mental requirements of the lowest savages, such as the Australians or the Andaman Islanders, are very little above those of many animals. How then was an organ developed far beyond the needs of its possessor? Natural Selection could only have endowed the savage with a brain a little superior to that of an ape, whereas he actually possesses one but very little inferior to that of the average members of our learned societies.

(Please note the language that, were we to judge the man solely by his descriptors for indigenous peoples, would lead us to label Wallace a racist even though he was in his own time what we would today call a progressive liberal.)

Since natural selection was the only law of nature Wallace knew of to explain the development of these structures, and since he determined that it could not adequately do so, he concluded that "an Overruling Intelligence has watched over the action of those laws, so directing variations and so determining their accumulation, as finally to produce an organization sufficiently perfect to admit of, and even to aid in, the indefinite advancement of our mental and moral nature."

Natural selection is not prescient—it does not select for needs in the future. Nature did not know we would one day need a big brain in order to contemplate the heavens or compute complex mathematical problems; she merely selected amongst our ancestors those who were best able to survive and leave behind offspring. But since we are capable of such sublime and lofty mental functions, Wallace deduced, clearly natural selection could not have been the originator of a brain big enough to handle them. Thus the need to invoke an "Overruling Intelligence" for this apparent gap in the theory.

Why did Wallace retreat from his own theory of natural selection when it came to the human mind? The answer, in a word, is hyper-selectionism (or adaptationism), in which the current adaptive purpose of a structure or function must be explained by natural selection applied to the past. Birds presently use wings to fly, so if we cannot conceive of how natural selection could incrementally select for fractional wings that were fully functional at each partial stage (called "the problem of incipient stages") then some other force must have been at work. Darwin answered this criticism by demonstrating how present structures serve a purpose different from the one for which they were originally selected. Partial wings, for example, were not poorly designed flying structures but well designed thermoregulators. Stephen Jay Gould calls this process "exaptation" (ex-adaptation) and uses the Panda's thumb as his type specimen: it is not a poorly designed thumb but a radial sesamoid (wrist) bone modified by natural selection for stripping leaves off bamboo shoots.

Wallace's hyperselectionism and adaptationism were outlined more formally in an 1870 paper, "The Limits of Natural Selection as Applied to Man," in which he admitted up front the danger of proffering a force that is beyond those known to science: "I must confess that this theory has the disadvantage of requiring the intervention of some distinct individual intelligence…. It therefore implies that the great laws which govern the material universe were insufficient for this production, unless we consider…that the controlling action of such higher intelligences is a necessary part of those laws…."

After an extensive analysis of brain size differences between humans and non-human primates, Wallace then considers such abstractions as law, government, science, and even such games as chess (a favorite pastime of his), noting that "savages" lack all such advances. Even more, "Any considerable development of these would, in fact, be useless or even hurtful to him, since they would to some extent interfere with the supremacy of those perceptive and animal faculties on which his very existence often depends, in the severe struggle he has to carry on against nature and his fellow-man. Yet the rudiments of all these powers and feelings undoubtedly exist in him, since one or other of them frequently manifest themselves in exceptional cases, or when some special circumstances call them forth."

Therefore, he concludes, "the general, moral, and intellectual development of the savage is not less removed from that of civilised man than has been shown to be the case in the one department of mathematics; and from the fact that all the moral and intellectual faculties do occasionally manifest themselves, we may fairly conclude that they are always latent, and that the large brain of the savage man is much beyond his actual requirements in the savage state." Thus, "A brain one-half larger than that of the gorilla would, according to the evidence before us, fully have sufficed for the limited mental development of the savage; and we must therefore admit that the large brain he actually possesses could never have been solely developed by any of those laws of evolution…. The brain of prehistoric and of savage man seems to me to prove the existence of some power distinct from that which has guided the development of the lower animals through their ever-varying forms of being."

The middle sections of this lengthy paper review additional human features that Wallace could not conceive of being evolved by natural selection: the distribution of body hair, naked skin, feet and hands, the voice box and speech, the ability to sing, artistic notions of form, color, and composition, mathematical reasoning and geometrical spatial abilities, morality and ethical systems, and especially such concepts as space and time, eternity and infinity. "How were all or any of these faculties first developed, when they could have been of no possible use to man in his early stages of barbarism? How could natural selection, or survival of the fittest in the struggle for existence, at all favour the development of mental powers so entirely removed from the material necessities of savage men, and which even now, with our comparatively high civilisation, are, in their farthest developments, in advance of the age, and appear to have relation rather to the future of the race than to its actual status?"

Modern Intelligent Design creationists generally (with few exceptions) believe that the designer is God. Nowhere in this paper does Wallace invoke God as the overarching intelligence. In a footnote in the second edition of the volume in which this paper was published, in fact, Wallace upbraids those who accused him of such speculations:

Some of my critics seem quite to have misunderstood my meaning in this part of the argument. They have accused me of unnecessarily and unphilosophically appealing to "first causes" in order to get over a difficulty—of believing that "our brains are made by God and our lungs by natural selection;" and that, in point of fact, "man is God's domestic animal." … Now, in referring to the origin of man, and its possible determining causes, I have used the words "some other power"—"some intelligent power"—"a superior intelligence"—"a controlling intelligence," and only in reference to the origin of universal forces and laws have I spoken of the will or power of "one Supreme Intelligence." These are the only expressions I have used in alluding to the power which I believe has acted in the case of man, and they were purposely chosen to show that I reject the hypothesis of "first causes" for any and every special effect in the universe, except in the same sense that the action of man or of any other intelligent being is a first cause. In using such terms I wished to show plainly that I contemplated the possibility that the development of the essentially human portions of man's structure and intellect may have been determined by the directing influence of some higher intelligent beings, acting through natural and universal laws.

Clearly Wallace's heresy had nothing to do with God or any other supernatural force, as these "natural and universal laws" could be fully incorporated into the type of empirical science he practiced. It was not spiritualism, but scientism at work in Wallace's world-view: "These speculations are usually held to be far beyond the bounds of science; but they appear to me to be more legitimate deductions from the facts of science than those which consist in reducing the whole universe…to matter conceived and defined so as to be philosophically inconceivable."

In Wallace's science there is no supernatural. There is only the natural and unexplained phenomenon yet to be incorporated into the natural sciences. That he left no room in his evolutionary theory for exaptations of early structures for later use is no reflection on his ambitions and abilities as a scientist. It was, in fact, one of Wallace's career goals to be the scientist who brought more of the apparent supernatural into the realm of the natural, and the remainder of his life was devoted to fleshing out the details of a scientism that encompassed so many different issues and controversies that made him a heretic-scientist.

If modern Intelligent Design theorists restricted their visage to only natural causes they would, perchance, be taken more seriously by the scientific community, who at present (myself included) sees this movement as nothing more than another species of the genus Homo creationopithicus.

January 18, 2012

Singularity 101: Be Skeptical! (Even of Skeptics)

Michael Shermer appeared on the Singularity 1 on 1 podcast after meeting its creator, Nikola (a.k.a "Socrates"), at a recent Singularity Summit in New York (watch Michael's lecture). Discussion included a variety of topics such as: Michael's education at a Christian college and original interest in religion and theology; his eventual transition to atheism, skepticism, science and the scientific method; SETI, the singularity and religion; scientific progress and the dots on the curve as precursors of big breakthroughs; life-extension, cloning and mind uploading; being a skeptic and an optimist at the same time; the "social singularity"; global warming; the tricky balance between being a skeptic while still being able to learn and make progress.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST AUDIO, or watch the videos below:

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Life has Never Been So Good?

Michael Shermer appears on MSNBC's Dylan Ratigan show to discuss why life is so much better now than in any other time in history.

Michael Shermer's Blog

- Michael Shermer's profile

- 1155 followers