Michael Shermer's Blog, page 10

October 1, 2013

When Science Doesn’t Support Beliefs

Ever since college I have been a libertarian—socially liberal and fiscally conservative. I believe in individual liberty and personal responsibility. I also believe in science as the greatest instrument ever devised for understanding the world. So what happens when these two principles are in conflict? My libertarian beliefs have not always served me well. Like most people who hold strong ideological convictions, I find that, too often, my beliefs trump the scientific facts. This is called motivated reasoning, in which our brain reasons our way to supporting what we want to be true. Knowing about the existence of motivated reasoning, however, can help us overcome it when it is at odds with evidence.

Take gun control. I always accepted the libertarian position of minimum regulation in the sale and use of firearms because I placed guns under the beneficial rubric of minimal restrictions on individuals. Then I read the science on guns and homicides, suicides and accidental shootings (summarized in my May column) and realized that the freedom for me to swing my arms ends at your nose. The libertarian belief in the rule of law and a potent police and military to protect our rights won’t work if the citizens of a nation are better armed but have no training and few restraints. Although the data to convince me that we need some gun-control measures were there all along, I had ignored them because they didn’t fit my creed. In several recent debates with economist John R. Lott, Jr., author of More Guns, Less Crime, I saw a reflection of my former self in the cherry picking and data mining of studies to suit ideological convictions. We all do it, and when the science is complicated, the confirmation bias (a type of motivated reasoning) that directs the mind to seek and find confirming facts and ignore disconfirming evidence kicks in.

My libertarianism also once clouded my analysis of climate change. I was a longtime skeptic, mainly because it seemed to me that liberals were exaggerating the case for global warming as a kind of secular Millenarianism—an environmental apocalypse requiring drastic government action to save us from doomsday through countless regulations that would handcuff the economy and restrain capitalism, which I hold to be the greatest enemy of poverty. Then I went to the primary scientific literature on climate and discovered that there is convergent evidence from multiple lines of inquiry that global warming is real and human-caused: temperatures increasing, glaciers melting, Arctic ice vanishing, Antarctic ice cap shrinking, sea-level rise corresponding with the amount of melting ice and thermal expansion, carbon dioxide touching the level of 400 parts per million (the highest in at least 800,000 years and the fastest increase ever), and the confirmed prediction that if anthropogenic global warming is real the stratosphere and upper troposphere should cool while the lower troposphere should warm, which is the case.

The clash between scientific facts and ideologies was on display at the 2013 FreedomFest conference in Las Vegas—the largest gathering of libertarians in the world—where I participated in two debates, one on gun control and the other on climate change. I love FreedomFest because it supercharges my belief engine. But this year I was so discouraged by the rampant denial of science that I wanted to turn in my libertarian membership card. At the gun-control debate (as in my debates with Lott around the country), proposing even modest measures that would have almost no effect on freedom—such as background checks—brought on opprobrium as if I had burned a copy of the U.S. Constitution on stage. In the climate debate, when I showed that between 90 and 98 percent of climate scientists accept anthropogenic global warming, someone shouted, “LIAR!” and stormed out of the room.

Liberals and conservatives are motivated reasoners, too, of course, and not all libertarians deny science, but all of us are subject to the psychological forces at play when it comes to choosing between facts and beliefs when they do not mesh. In the long run, it is better to understand the way the world really is rather than how we would like it to be.

September 1, 2013

The Dangers of Keeping an Open Mind

“Alien abductors have asked him to probe them.” “Sasquatch has taken a photograph of him.” The “him” is the “Most Interesting Man in the World,” the faux character in the Dos Equis beer ad campaign, and these are my favorite skeptical lines from a litany of superfluities and braggadocios. (“In a past life, he was himself.”)

My candidate for the most interesting scientist in history I’d like to have a beer with is Alfred Russel Wallace, the 19th-century naturalist and co-discoverer (with Charles Darwin) of natural selection, whose death centennial we will marking this November. As I document in my 2002 biography of him— In Darwin’s Shadow (Oxford University Press)—Wallace was a grand synthesizer of biological data into a few core principles that revolutionized biogeography, zoology and evolutionary theory. He spent four years exploring the Amazon rain forest but lost most of his collections when his ship sank on his way home. His discovery of natural selection came during an eight-year expedition to the Malay Archipelago, where during a malaria-induced fever, it struck him that the best fit organisms are more likely to survive and reproduce.

Being open-minded enough to make great discoveries, however, can often lead scientists to make great blunders. Wallace, for example, was also a firm believer in phrenology, spiritualism and psychic phenomena, evidence for which he collected at séances over the objections of his more skeptical colleagues. Among them was Thomas Henry Huxley, who growled, “Better live a crossing-sweeper than die and be made to talk twaddle by a ‘medium’ hired at a guinea a séance.”

Wallace’s adventurous spirit led him to become ahead of his time in opposing eugenics and wasteful militarism and in defending women’s rights and wildlife preservation. Yet he was on the wrong side when he led an antivaccination campaign. He was a first-class belletrist, but he fell for a scam over a “lost poem” that Edgar Allan Poe allegedly wrote to cover a hotel bill in California. Worst of all, he scientifically departed from Darwin over the evolution of the human brain, which Wallace could not conceive as being the product of natural selection alone (because other primates succeed with much smaller brains) and thus must have been designed by a higher power. Darwin snarled, “I hope you have not murdered too completely your own and my child.”

Wallace is the prototype of what I call a “heretic scientist,” someone whose mind is porous enough to let through both revolutionary and ridiculous ideas at the same time. Other such examples abound in astrophysicist Mario Livio’s 2013 book, Brilliant Blunders (Simon & Schuster), in which he skillfully narrates the principle that “not only is the road to triumph paved with blunders, but the bigger the prize, the bigger the potential blunder.” Livio’s list includes Darwin’s stumble in postulating the incorrect theory of pangenesis, based on the inheritance of particles he called gemmules that carried traits from parents to offspring; Lord Kelvin’s gaffe of underestimating the age of the earth by almost 50 times, not because he ignored radioactivity, Livio argues, but because he dismissed the possibility of heat-transport mechanisms such as convection; Linus Pauling’s misstep in building a DNA model as a triple helix inside out (because he rushed his research in the race against Francis Crick and James Watson); Fred Hoyle’s bungle of siding with the steady state model of the universe over what he dismissively called the “big bang” model despite overwhelming evidence of the latter. As for Albert Einstein’s “biggest blunder” of adding a “cosmological constant” into his equations to account for the expanding universe, Livio claims Einstein never said it: instead Einstein applied the notion of “aesthetic simplicity” in his physical theories, which led him to reject the cosmological constant as an unnecessary complication to the equations.

How can we avoid such errors? Livio quotes Bertrand Russell: “Do not feel absolutely certain of anything.” He then conveys a central principle of skepticism: “While doubt often comes across as a sign of weakness, it is also an effective defense mechanism, and it’s an essential operating principle for science.”

August 1, 2013

Five Myths of Terrorism

Because terrorism educes such strong emotions, it has led to at least five myths. The first began in September 2001, when President George W. Bush announced that “we will rid the world of the evildoers” and that they hate us for “our freedoms.” This sentiment embodies what Florida State University psychologist Roy Baumeister calls “the myth of pure evil,” which holds that perpetrators commit pointless violence for no rational reason.

This idea is busted through the scientific study of aggression, of which psychologists have identified four types that are employed toward a purposeful end (from the perpetrators’ perspective): instrumental violence, such as plunder, conquest and the elimination of rivals; revenge, such as vendettas against adversaries or self-help justice; dominance and recognition, such as competition for status and women, particularly among young males; and ideology, such as religious beliefs or utopian creeds. Terrorists are motivated by a mixture of all four.

In a study of 52 cases of Islamist extremists who have targeted the U.S. for terrorism, for example, Ohio State University political scientist John Mueller concluded that their motives are often instrumental and revenge-oriented, a “boiling outrage at U.S. foreign policy—the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, in particular, and the country’s support for Israel in the Palestinian conflict.” Ideology in the form of religion “was a part of the consideration for most,” Mueller suggests, “but not because they wished to spread Sharia law or to establish caliphates (few of the culprits would be able to spell either word). Rather they wanted to protect their co-religionists against what was commonly seen to be a concentrated war on them in the Middle East by the U.S. government.”

As for dominance and recognition, University of Michigan anthropologist Scott Atran has demonstrated that suicide bombers (and their families) are showered with status and honor in this life and the promise of women in the next and that most “belong to loose, homegrown networks of family and friends who die not just for a cause but for each other.” Most terrorists are in their late teens or early 20s and “are especially prone to movements that promise a meaningful cause, camaraderie, adventure and glory,” he adds.

Busting a second fallacy—that terrorists are part of a vast global network of top-down centrally controlled conspiracies against the West—Atran shows that it is “a decentralized, self-organizing and constantly evolving complex of social networks.” A third flawed notion is that terrorists are diabolical geniuses, as when the 9/11 Commission report de – scribed them as “sophisticated, patient, disciplined, and lethal.” But according to Johns Hopkins University political scientist Max Abrahms, after the decapitation of the leadership of the top extremist organizations, “terrorists targeting the American homeland have been neither sophisticated nor masterminds, but incompetent fools.”

Examples abound: the 2001 airplane shoe bomber Richard Reid was unable to ignite the fuse because it was wet from rain; the 2009 underwear bomber Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab succeeded only in torching his junk; the 2010 Times Square bomber Faisal Shahzad managed merely to burn the inside of his Nissan Pathfinder; and the 2012 model airplane bomber Rezwan Ferdaus purchased faux C-4 explosives from FBI agents. Most recently, the 2013 Boston Marathon bombers were equipped with only one gun and had no exit strategy beyond hijacking a car low on gas that Dzhokhar Tsarnaev used to run over his brother, Tamerlan, followed by a failed suicide attempt inside a land-based boat.

A fourth fiction is that terrorism is deadly. Compared with the annual average of 13,700 homicides, however, deaths from terrorism are statistically invisible, with a total of 33 in the U.S. since 9/11. Finally, a fifth figment about terrorism is that it works. In an analysis of 457 terrorist campaigns since 1968, George Mason University political scientist Audrey Cronin found that not one extremist group conquered a state and that a full 94 percent failed to gain even one of their strategic goals. Her 2009 book is entitled How Terrorism Ends (Princeton University Press). It ends swiftly (groups survive eight years on average) and badly (the death of its leaders).

We must be vigilant always, of course, but these myths point to the inexorable conclusion that terrorism is nothing like what its perpetrators wish it were.

July 1, 2013

Gods of the Gaps

According to the popular series Ancient Aliens, on H2 (a spinoff of the History channel), extraterrestrial intelligences visited Earth in the distant past, as evidenced by numerous archaeological artifacts whose scientific explanations prove unsatisfactory for alien enthusiasts. The series is the latest in a genre launched in 1968 by Erich von Däniken, whose book Chariots of the Gods? became an international best seller. It spawned several sequels, including Gods from Outer Space, The Gods Were Astronauts and, just in time for the December 21, 2012, doomsday palooza, Twilight of the Gods: The Mayan Calendar and the Return of the Extraterrestrials (the ones who failed to materialize).

Ancient aliens theory is grounded in a logical fallacy called argumentum ad ignorantiam, or “argument from ignorance.” The illogical reasoning goes like this: if there is no satisfactory terrestrial explanation for, say, the Nazca lines of Peru, the Easter Island statues or the Egyptian pyramids, then the theory that they were built by aliens from outer space must be true.

Whereas the talking heads of Ancient Aliens conjecture that ETs used “acoustic stone levitation” to build the pyramids, for example, archaeologists have discovered images demonstrating how tens of thousands of Egyptian workers employed wood sleds to move the stones along roads from the quarry to the site and then hauled them up gently sloping dirt ramps of an ever growing pyramid. Copper drills, chisels, saws and awls have been found in the rubble around the Great Pyramid of Giza, and the quarries are filled with half-finished blocks and broken tools that show how the Egyptians worked the stone. Conspicuously absent from the archaeological record are any artifacts more advanced than those known to be used in the third millennium B.C.

Another alleged aliens artifact is a symbol found in the Egyptian Dendera Temple complex that vaguely resembles a modern lightbulb, with a squiggly filament inside and a plug at the bottom. Instead of featuring archaeologists who would explain that the symbol depicts a creation myth of the time (the “plug” is a lotus flower that represents life arising from the primordial waters, and the “filament” signifies a snake), ancient aliens fantasists speculate that the Egyptians were given the power of electricity by the gods. In this “if this were true, what else would be true?” line of inquiry, it is telling that no electrical wires, glass bulbs, metal filaments or electric power stations have ever been excavated.

On the lid of the sarcophagus of the Mayan king Pakal in Mexico is a “rocketlike” image that Ancient Aliens consulting producer Giorgio Tsoukalos claims depicts the ruler in a spaceship: “He is at an angle like modern-day astronauts upon liftoff. He is manipulating some controls. He has some type of breathing apparatus or some type of a telescope in front of his face. His feet are on some type of a pedal. And you have something that looks like an exhaust—with flames.” According to Mayan archaeologists, however, this depiction shows King Pakal sitting atop the sun monster and descending into the underworld (where the sun goes at night) within a “world tree”—a classic mythological symbol, with branches stretched into the heavens and roots dug into the underworld.

Ancient aliens arguments from ignorance resemble intelligent design “God of the gaps” arguments: wherever a gap in scientific knowledge exists, there is evidence of divine design. In this way, ancient aliens serve as small “g” gods of the archaeological gaps, with the same shortcoming as the gods of the evolutionary gaps—the holes are already filled or soon will be, and then whence goes your theory? In science, for a new theory to be accepted, it is not enough to identify only the gaps in the prevailing theory (negative evidence). Proponents must provide positive evidence in favor of their new theory. And as skeptics like to say, before you say something is out of this world, first make sure that it is not in this world.

Tellingly, in subsequent printings of Chariots of the Gods? the question mark was quietly dropped, and this disqualifier was added on the copyright page: “This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.” Gap closed.

June 1, 2013

CSI, Science

IN HIS BEST-SELLING ESSAY entitled “Guns,” Stephen King contrasts a mass killer’s school yearbook picture, “in which the guy pretty much looks like anybody,” and the police mug shot of someone who looks “like your worst nightmare.”

Do criminals look different from noncriminals? Are there patterns that science can discover to enable society to identify potential felons before they break the law or to rehabilitate them after? University of Pennsylvania criminologist and psychiatrist Adrian Raine attempts to answer these and related questions his book The Anatomy of Violence: The Biological Roots of Crime (Pantheon, 2013). Raine details how evolutionary psychology and neuroscience are converging in this effort. For example, he contrasts two cases that show new ways to look at the origins of wrongdoing. First is the example of “Mr. Oft,” a perfectly normal man turned into a pedophile by a massive tumor at the base of his orbitofrontal cortex; when it was resected, he returned to normalcy. Second, we learn of a murderer-rapist named Donta Page, whose childhood was so horrifically bad—he was impoverished, malnourished, fatherless, abused, raped and beaten on the head to the point of being hospitalized several times—that his brain scan “showed clear evidence of reduced functioning in the medial and orbital regions of the prefrontal cortex.”

The significance of these examples is revealed when Raine reviews the brain scans he made of 41 murderers, in which he found significant impairment of their prefrontal cortex. Such damage “results in a loss of control over the evolutionarily more primitive parts of the brain, such as the limbic system, that generate raw emotions like anger and rage.” Research on neurological patients in general, Raine adds, shows that “damage to the prefrontal cortex results in [increased] risk-taking, irresponsibility, and rule-breaking behavior,” along with personality changes such as “impulsivity, loss of self-control, and an inability to modify and inhibit behavior appropriately” and cognitive impairment such as a “loss of intellectual flexibility and poorer problem-solving skills” that may later result in “school failure, unemployment, and economic deprivation, all factors that predispose someone to a criminal and violent way of life.”

What is the difference between an aggressive tumor and a violent upbringing? One is clearly biological, whereas the other results from a complex web of biosocial factors. Yet, Raine points out, both can lead to troubling moral and legal questions: “If you agree that Mr. Oft was not responsible for his actions because of his orbitofrontal tumor, what judgment would you render on someone who committed the same act as Mr. Oft but, rather than having a clearly visible tumor, had a subtle prefrontal pathology with a neurodevelopmental origin that was hard to see visually from a PET scan?” A tumor is quickly treatable, but an upbringing— not so much.

We also need an evolutionary psychology of violence and aggression. “From rape to robbery and even to theft, evolution has made violence and antisocial behavior a profitable way of life for a small minority of the population,” Raine writes. Theft can grant the perpetrator more resources necessary for survival and reproduction. A reputation for being aggressive can grant males higher status in the pecking order of social dominance. Revenge murders are an evolved strategy for dealing with cheaters and free riders. Even child murder has an evolutionary logic to it, as evidenced by the statistic that children are 100 times more likely to be murdered by their stepfather, who would have an interest in passing on his own genes over a rival’s, than their natural father.

An evolutionary psychology and neuroscience of criminology is the next and necessary step toward producing a more moral world. In Raine’s concluding remarks, he exhorts us to “rise above our feelings of retribution, reach out for rehabilitation, and en gage in a more humane discourse on the causes of violence.” Al though some people may balk at the biological determinism inherent in such an approach and others may recoil from the preference for rehabilitation over retribution, we can all benefit from a scientific understanding of the true causes of crime.

May 6, 2013

May 1, 2013

Gun Science

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 31,672 people died by guns in 2010 (the most recent year for which U.S. figures are available), a staggering number that is orders of magnitude higher than that of comparable Western democracies. What can we do about it? National Rifle Association executive vice president Wayne LaPierre believes he knows: “The only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.” If La Pierre means professionally trained police and military who routinely practice shooting at ranges, this observation would at least be partially true. If he means armed private citizens with little to no training, he could not be more wrong.

Consider a 1998 study in the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery that found that “every time a gun in the home was used in a self-defense or legally justifiable shooting, there were four unintentional shootings, seven criminal assaults or homicides, and 11 attempted or completed suicides.” Pistol owners’ fantasy of blowing away home-invading bad guys or street toughs holding up liquor stores is a myth debunked by the data showing that a gun is 22 times more likely to be used in a criminal assault, an accidental death or injury, a suicide attempt or a homicide than it is for selfdefense. I harbored this belief for the 20 years I owned a Ruger .357 Magnum with hollow-point bullets designed to shred the body of anyone who dared to break into my home, but when I learned about these statistics, I got rid of the gun.

More insights can be found in a 2013 book from Johns Hopkins University Press entitled Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis, edited by Daniel W. Webster and Jon S. Vernick, both professors in health policy and management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. In addition to the 31,672 people killed by guns in 2010, another 73,505 were treated in hospital emergency rooms for nonfatal bullet wounds, and 337,960 nonfatal violent crimes were committed with guns. Of those 31,672 dead, 61 percent were suicides, and the vast majority of the rest were homicides by people who knew one another.

For example, of the 1,082 women and 267 men killed in 2010 by their intimate partners, 54 percent were by guns. Over the past quarter of a century, guns were involved in greater number of intimate partner homicides than all other causes combined. When a woman is murdered, it is most likely by her intimate partner with a gun. Regardless of what really caused Olympic track star Oscar Pistorius to shoot his girlfriend, Reeva Steenkamp (whether he mistook her for an intruder or he snapped in a lover’s quarrel), her death is only the latest such headline. Recall, too, the fate of Nancy Lanza, killed by her own gun in her own home in Connecticut by her son, Adam Lanza, before he went to Sandy Hook Elementary School to murder some two dozen children and adults. As an alternative to arming women against violent men, legislation can help: data show that in states that prohibit gun ownership by men who have received a domestic violence restraining order, gun-caused homicides of intimate female partners were reduced by 25 percent.

Another myth to fall to the facts is that gun-control laws disarm good people and leave the crooks with weapons. Not so, say the Johns Hopkins authors: “Strong regulation and oversight of licensed gun dealers—defined as having a state law that required state or local licensing of retail firearm sellers, mandatory record keeping by those sellers, law enforcement access to records for inspection, regular inspections of gun dealers, and mandated reporting of theft of loss of firearms—was associated with 64 percent less diversion of guns to criminals by in-state gun dealers.” Finally, before we concede civilization and arm everyone to the teeth pace the NRA, consider the primary cause of the centurieslong decline of violence as documented by Steven Pinker in his 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature: the rule of law by states that turned over settlement of disputes to judicial courts and curtailed private self-help justice through legitimate use of force by police and military trained in the proper use of weapons.

April 1, 2013

Proof of Hallucination

In Eben Alexander’s best-selling book Proof of Heaven: A Neurosurgeon’s Journey into the Afterlife (Simon & Schuster), he recounts his near-death experience (NDE) during a meningitis-induced coma. When I first read that Alexander’s heaven includes “a beautiful girl with high cheekbones and deep blue eyes” who offered him unconditional love, I thought, “Yeah, sure, dude. I’ve had that fantasy, too.” Yet when I met him on the set of Larry King’s new streaming-live talk show on Hulu, I realized that he genuinely believes he went to heaven. Did he?

Not likely. First, Alexander claims that his “cortex was completely shut down” and that his “near-death experience … took place not while [his] cortex was malfunctioning, but while it was simply off.” In King’s green room, I asked him how, if his brain was really nonfunctional, he could have any memory of these experiences, given that memories are a product of neural activity? He responded that he believes the mind can exist separately from the brain. How, where, I inquired? That we don’t yet know, he rejoined. The fact that mind and consciousness are not fully explained by natural forces, however, is not proof of the supernatural. In any case, there is a reason they are called near-death experiences: the people who have them are not actually dead.

Second, we now know of a number of factors that produce such fantastical hallucinations, which are masterfully explained by the great neurologist Oliver Sacks in his 2012 book Hallucinations (Knopf ). For example, Swiss neuroscientist Olaf Blanke and his colleagues produced a “shadow person” in a patient by electrically stimulating her left temporoparietal junction. “When the woman was lying down,” Sacks reports, “a mild stimulation of this area gave her the impression that someone was behind her; a stronger stimulation allowed her to define the ‘someone’ as young but of indeterminate sex.”

Sacks recalls his experience treating 80 deeply parkinsonian postencephalitic patients (as seen in the 1990 film Awakenings, which starred Robin Williams in a role based on Sacks), and notes, “I found that perhaps a third of them had experienced visual hallucinations for years before “L-dopa was introduced—hallucinations of a predominantly benign and sociable sort.” He speculates that “it might be related to their isolation and social deprivation, their longing for the world—an attempt to provide a virtual reality, a hallucinatory substitute for the real world which had been taken from them.”

Migraine headaches also produce hallucinations, which Sacks himself has experienced as a longtime sufferer, including a “shimmering light” that was “dazzlingly bright”: “It expanded, becoming an enormous arc stretching from the ground to the sky, with sharp, glittering, zigazgging borders and brilliant blue and orange colors.” Compare Sacks’s experience with that of Alexander’s trip to heaven, where he was “in a place of clouds. Big, puffy, pink-white ones that showed up sharply against the deep blue-black sky. Higher than the clouds—immeasurably higher—flocks of transparent, shimmering beings arced across the sky, leaving long, streamerlike lines behind them.”

In an article in the Atlantic last December, Sacks explains that the reason hallucinations seem so real “is that they deploy the very same systems in the brain that actual perceptions do. When one hallucinates voices, the auditory pathways are activated; when one hallucinates a face, the fusiform face area, normally used to perceive and identify faces in the environment, is stimulated.” Sacks concludes that “the one most plausible hypothesis in Dr. Alexander’s case, then, is that his NDE occurred not during his coma, but as he was surfacing from the coma and his cortex was returning to full function. It is curious that he does not allow this obvious and natural explanation, but instead insists on a supernatural one.”

The reason people turn to supernatural explanations is that the mind abhors a vacuum of explanation. Because we do not yet have a fully natural explanation for mind and consciousness, people turn to supernatural explanations to fill the void. But what is more likely: That Alexander’s NDE was a real trip to heaven and all these other hallucinations are the product of neural activity only? Or that all such experiences are mediated by the brain but seem real to each experiencer? To me, this evidence is proof of hallucination, not heaven.

March 1, 2013

Dictators and Diehards

on earth

In Tyler Hamilton’s 2012 book The Secret Race (written with Daniel Coyle), the cyclist exposes the most sophisticated doping program in the history of sports, orchestrated by Lance Armstrong, the seven-time Tour de France winner now stripped of his titles after a thorough investigation by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency. Hamilton shows how such an elaborate system was maintained through the “omertà rule”—the code of silence that leads one to believe everyone else believes doping is the norm—and reinforced by the threat of punishment for speaking out or not complying.

The broader psychological principle at work here is “pluralistic ignorance,” in which individual members of a group do not believe something but mistakenly believe everyone else in the group believes it. When no one speaks up, it produces a “spiral of silence” that can lead to everything from binge drinking and hooking up to witch hunts and deadly ideologies. A 1998 study by Christine M. Schroeder and Deborah A. Prentice, for example, found that “the majority of students believe that their peers are uniformly more comfortable with campus alcohol practices than they are.” Another study in 1993 by Prentice and Dale T. Miller found a gender difference in drinking attitudes in which “male students shifted their attitudes over time in the direction of what they mistakenly believed to be the norm, whereas female students showed no such attitude change.” Women, however, were not immune to pluralistic ignorance when it comes to hooking up, as shown in a 2003 study by Tracy A. Lambert and her colleagues, who found “both women and men rated their peers as being more comfortable engaging in these behaviors than they rated themselves.”

When you add an element of punishment for those who challenge the norm, pluralistic ignorance can transmogrify into purges, pogroms and repressive political regimes. European witch hunts, like their Soviet counterparts centuries later, degenerated into preemptive accusations of guilt, lest one be thought guilty first. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn described a party conference in which Joseph Stalin was given a standing ovation that went on for 11 minutes, until a factory director finally sat down to the relief of everyone. The man was arrested later that night and sent to the gulag for a decade. A 2009 study by Michael Macy and his colleagues confirmed the effect: “People enforce unpopular norms to show that they have complied out of genuine conviction and not because of social pressure.”

Bigotry is ripe for the effects of pluralistic ignorance, as evidenced in a 1975 study by Hubert J. O’Gorman, which indicated that “in 1968 most white American adults grossly exaggerated the support among other whites for racial segregation,” especially among those leading segregated lives, which reinforces the spiral of silence.

Fortunately, there is a way to break this spiral of ignorance: knowledge and communication. Tyler’s confession led to the admission of doping by others, thereby breaking the code of silence and leading to openness about cleaning up the sport. In the Schroeder and Prentice study on college binge drinking, they found that exposing incoming freshmen to a peer-directed discussion that included an explanation of pluralistic ignorance and its effects significantly reduced subsequent student alcoholic intake. Moreover, Macy and his colleagues found that when skeptics are scattered among true believers in a computer simulation of a society in which there is ample opportunity for interaction and communication, social connectedness acted as a prophylactic against un popular norms taking over.

This is why totalitarian and theocratic regimes restrict speech, press, trade and travel and why the route to breaking the bonds of such repressive governments and ideologies is the spread of liberal democracy and open borders. This is why even here in the U.S.—the land of the free—we must openly endorse the rights of gays and atheists to be treated equally under the law and why “coming out” helps to break the spiral of silence. Knowledge and communication, especially when generated by science and technology, o!er our last best hope on earth.

February 12, 2013

Towards a Science of Morality: A Reply to Massimo Pigliucci

In this year’s annual Edge.org question “What should we be worried about?” I answered that we should be worried about “ The Is-Ought Fallacy of Science and Morality.” I wrote: “We should be worried that scientists have given up the search for determining right and wrong and which values lead to human flourishing”. Evolutionary biologist and philosopher of science Massimo Pigliucci penned a thoughtful response, which I appreciate given his dual training in science and philosophy, including and especially evolutionary theory, a perspective that I share. But he felt that my scientific approach added nothing new to the philosophy of morality, so let me see if I can restate my argument for a scientific foundation of moral principles with new definitions and examples.

First, morality is derived from the Latin moralitas, or “manner, character, and proper behavior.” Morality has to do with how you act toward others. So I begin with a Principle of Moral Good:

Always act with someone else’s moral good in mind, and never act in a way that it leads to someone else’s moral loss (through force or fraud).

You can, of course, act in a way that has no effect on anyone else, and in this case morality isn’t involved. But given the choice between acting in a way that increases someone else’s moral good or not, it is more moral to do so than not. I added the parenthetical note “through force or fraud” to clarify intent instead of, say, neglect or acting out of ignorance. Morality involves conscious choice, and the choice to act in a manner that increases someone else’s moral good, then, is a moral act, and its opposite is an immoral act.

Given this moral principle, the central question is this: On what foundation should we ground our moral decisions? We have to ground the foundations of morality on something, and we secularists (skeptics, humanists, atheists, et al.) are in agreement that “divine command theory” is untenable not only because there probably is no God, but even if there is a God divine command theory was refuted 2500 years ago by Plato through his “Euthyphro’s dilemma,” in which he asked “whether the pious or holy is beloved by the gods because it is holy, or holy because it is beloved of the gods?”, showing how it must be the former—moral principles must stand on their own with or without God. Rape, for example, is wrong whether or not God says it is wrong (in the Bible, in fact, God offers no prohibition against rape, and in fact seems to encourage it in many instances as a perquisite of war for victors). Adultery, which is prohibited in the Bible, would still be wrong even if it were not listed in the Decalogue.

How do we know that rape and adultery are wrong? We don’t need to ask God. We need to ask the affected moral agent—the rape victim in question, or our spouse or romantic partner who is being cuckold. They will let you know instantly and forcefully precisely how they feel morally about that behavior.

Here we see that the Golden Rule (“Do unto others as you would have them do unto you”) has a severe limitation to it: What if the moral receiver thinks differently from the moral doer? What if you would not mind having action X done unto you, but someone else would mind it? Most men, for example, are much more receptive toward unsolicited offers of sex than are women. Most men, then, in considering whether to approach a woman with an offer of unsolicited sex, should not ask themselves how they would feel as a test. This is why in my book The Science of Good and Evil I introduced the Ask-First Principle:

To find out whether an action is right or wrong, ask first.

The moral doer should ask the moral receiver whether the behavior in question is moral or immoral. If you aren’t sure that the potential recipient of your action will react in the same manner you would react to the moral behavior in question, then ask…before you act. (This principle applies to rational sane adults and not to children or mentally ill adults. Asking a 12-year old girl raised in a polygamous family belonging to the Fundamentalist Latter Day Saints if she feels it is moral to marry a man in his 60s who is already married to many other women is not a rational test because she does not have the capacity for moral reasoning.)

But what is the foundation for why we should care about the feelings of potentially affected moral agents? To answer this question I turn to science and evolutionary theory.

Given that moral principles must be founded on something natural instead of supernatural, and that science is the best tool we have devised for understanding the natural world, applying evolutionary theory to not only the origins of morality but to its ultimate foundation as well, it seems to me that the individual is a reasonable starting point because, (1) the individual is the primary target of natural selection in evolution, and (2) it is the individual who is most effected by moral and immoral acts. Thus:

The survival and flourishing of the individual is the foundation for establishing values and morals, and so determining the conditions by which humans best survive and flourish ought to be the goal of a science of morality.

Here we find a smooth transition from the way nature is (the individual struggling to survive and flourish in an evolutionary context) to the way it ought to be (given a choice, it is more moral to act in a way that enhances the survival and flourishing of other individuals). Here are three examples:

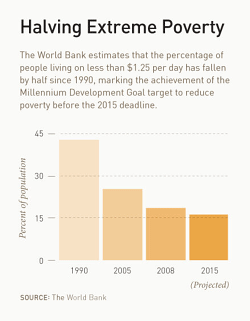

In his annual letter Bill Gates outlined how and why the progress of the human condition can best be implemented when tracked through scientific data: “I have been struck again and again by how important measurement is to improving the human condition. You can achieve amazing progress if you set a clear goal and find a measure that will drive progress toward that goal.”

One notable sign of progress is seen in this graph from Gates’ Annual Letter (right).

If the survival and flourishing of the individual is the foundation of values and morals, then this graph tracks moral progress because we can say objectively and absolutely that reducing extreme poverty by half since 1990 is real moral progress. On what basis can we make such a claim? Ask the people who are no longer living on less than $1.25 a day. They will tell you that living on more than $1.25 a day is absolutely better than living on less than $1.25 a day. Why is it better? Because individuals are more likely to survive and flourish when they have the basics of life.

This is why Bill Gates is backing with his considerable wealth and talent the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals program that is supported by 189 nations, in which the year 2015 was set as a deadline for making specific percentage improvements across a range of areas including health, education, and basic income. Gates reports, for example, that the number of polio cases has decreased from 350,000 in 1988 to 222 in 2012. Is that a moral good? Ask the 350,000 polio victims. They’ll tell you. Or ask the 5.1 million children under the age of 5 who didn’t die in 2011, who in 1990 would have died (Unicef reports that the number of children under 5 years old who died worldwide was 12 million in 1990 and 6.9 million in 2011).

Caption from Gates’ Annual Letter: Getting a closer look at charts documenting rural health progress at the Germana Gale Health Post in Ethiopia. Over the past year I’ve been impressed with progress in using data and measurement to improve the human condition (Dalocha, Ethiopia, 2012).

A second example may be found on the opposite end of the economic sale in a study conducted for the National Bureau of Economic Research entitled “Subjective Well-Being, Income, Economic Development and Growth” by the University of Pennsylvania economists Daniel Sacks, Betsey Stevenson, and Justin Wolfers, in which they compared survey data on subjective well-being (“happiness”) with income and economic growth rates in 140 countries. The economists found a positive correlation between income and happiness within individual countries, in which richer people are happier than poorer people; and they also found a between-country difference in which people in richer countries are happier than people in poorer countries. As well, they found that an increase in economic growth was associated with an increase in subjective well being: “These results together suggest that measured subjective well-being grows hand in hand with material living standards.” How much difference? “A 20 percent increase in income has the same impact on well-being, regardless of the initial level of income: going from $500 to $600 of income per year yields the same impact on well-being as going from $50,000 to $60,000 per year.” Contrary to previous studies, the economists found no upper limit in which more money does not correlate with more happiness. As well, on a 0–10 scale measuring “life satisfaction,” people in poor countries averaged a 3, people in middle-income countries averaged a 5–6, and people in rich countries averaged a 7–8 (Americans rate their life satisfaction as a 7.4). The economists’ conclusion confirms my moral science theory that the survival and flourishing of individuals is what counts:

The fact that life satisfaction and other measures of subjective well-being rise with income has significant implications for development economists. First, and most importantly, these findings cast doubt on the Easterlin Paradox and various theories suggesting that there is no long-term relationship between well-being and income growth. Absolute income appears to play a central role in determining subjective well-being. This conclusion suggests that economists’ traditional interest in economic growth has not been misplaced. Second, our results suggest that differences in subjective well-being over time or across places likely reflect meaningful differences in actual well-being.

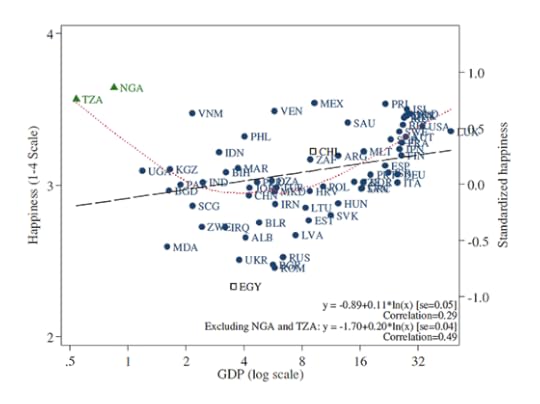

Here is the figure for the relationship between happiness and GDP from this study:

World Values Survey, 1999–2004, and author’s regressions. Sources for GDP per capita are described in the text. The happiness question asks, “Taking all things together, would you say you are: ‘very happy,’ ‘quite happy,’ ‘not very happy,’ [or] ‘not at all happy’?” Data are aggregated into country averages by first standardizing individual level data to have mean zero and standard deviation one, and then taking the within-country average of individual happiness. The dashed line plots fitted values from the reported OLS regression (including TZA and NGA); the dotted line gives fitted values from a lowess regressions. The regression coefficients are on the standardized scale. Both regressions are based on nationally representative samples. Observations represented by hollow squares are drawn from countries in which the World Values Survey sample is not nationally representative; see Stevenson and Wolfers (2008), appendix B, for further details. Sample includes sixty-nine developed and developing countries.

Why does money matter morally? Because it leads to a higher standard of living. Why does a higher standard of living matter morally? Because it increases the probability that an individual will survive and flourish. Why does survival and flourishing matter morally? Because it is the basis of the evolution of all life on earth through natural selection.

There are many more examples like these in which we can employ science to derive all sorts of findings that show how various social, political, and economic conditions lead to an increase or decrease of the survival and flourishing of individuals. This is why in my Edge.org essay I discussed data from political scientists and economists showing that democracies are better than dictatorships and that countries with more open economic borders and free trade are better off than countries with more closed economic borders and restricted trade (think North Korea, whose citizens are on average several inches shorter than their South Korean counterparts because of their crappy diets). These are measurable differences that allow us to draw scientific conclusions about moral progress or regress, based on the increase or decrease of the survival and flourishing of the individuals living in those countries. The fact that there may be many types of democracies (direct v. representative) and economies (with various trade agreements or membership in trading blocks) only reveals that human survival and flourishing is multi-faceted and multi-causal, and not that because there is more than one way to survive and flourish means that all political, economic, and social systems are equal. They are not equal, and we have the scientific data and historical examples to demonstrate which ones increase or decrease the survival and flourishing of individuals.

In this Feb. 6, 2013 photo, bystanders watch as a woman accused of witchcraft is burned alive in the Western Highlands provincial capital of Mount Hagen in Papua New Guinea.

(Credit: AP)

One final example on the regress side of the moral ledger: On Wednesday, February 6, 2013, a 20-year old woman and mother of one named Kepari Leniata was burned alive in the Western Highlands of Papua New Guinea because she was accused of sorcery by the relatives of a six-year-old boy who died on February 5. As in witch hunts of old, the conflagration on a pile of rubbish was preceded by torture with a hot iron rod, after which she was bound and doused in gasoline and ignited while surrounded by gawking crowds that prevented police and authorities from rescuing her. Tragically, a 2010 Oxfam study reported that beliefs in sorcery and witchcraft are not uncommon in the highlands of New Guinea, as well as in many parts of Melanesia in which many people still “do not accept natural causes as an explanation for misfortune, illness, accidents or death,” and instead place the blame for their problems on supernatural sorcery and black magic.

By now it seems risibly superfluous to explain why this is immoral and what the solution is, but in case there is any doubt: We know that belief in supernatural sorcery and witchcraft and their concomitant consequences of torturing and murdering whose so accused is wrong because it decreases the survival and flourishing of individuals—just ask first the woman about to be torched. The immediate solution is the enforcement of laws prohibiting such acts. The ultimate solution is science and education in understanding the natural causes of things and the debunking of supernatural beliefs in sorcery and witchcraft. And it is science that tells us why witchcraft and sorcery is immoral.

Note to my readers: What I am outlining here is the basis for my next book, The Moral Arc of Science, which I am researching and writing now, so I ask you to post your critiques here or email me your constructive criticisms. My role model is Charles Darwin, who solicited criticisms of his theory of evolution and included them in a chapter entitled “Difficulties on Theory” in On the Origin of Species. Of course, if you agree with me, and/or think of additional examples in support of my theory, then I would appreciate hearing those as well!

Michael Shermer's Blog

- Michael Shermer's profile

- 1155 followers