Michael Shermer's Blog, page 7

September 1, 2015

Forensic Pseudoscience

The criminal justice system has a problem, and its name is forensics. This was the message I heard at the Forensic Science Research Evaluation Workshop held May 26–27 at the AAAS headquarters in Washington, D.C. I spoke about pseudoscience but then listened in dismay at how the many fields in the forensic sciences that I assumed were reliable (DNA, fingerprints, and so on) in fact employ unreliable or untested techniques and show inconsistencies between evaluators of evidence.

The conference was organized in response to a 2009 publication by the National Research Council entitled Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward, which the U.S. Congress commissioned when it became clear that DNA was the only (barely) reliable forensic science. The report concluded that “the forensic science system, encompassing both research and practice, has serious problems that can only be addressed by a national commitment to overhaul the current structure that supports the forensic science community in this country.” Among the areas determined to be flawed and in need of more research are: accuracy and error rates of forensic analyses, sources of potential bias and human error in interpretation by forensic experts, fingerprints, firearms examination, tool marks, bite marks, impressions (tires, footwear), bloodstain-pattern analysis, handwriting, hair, coatings (for example, paint), chemicals (including drugs), materials (including fibers), fluids, serology, and fire and explosive analysis.

Take fire analysis. According to John J. Lentini, author of the definitive book Scientific Protocols for Fire Investigation (CRC Press, second edition, 2012), the field is filled with junk science. “What does that pattern of burn marks over there mean?” he recalled asking a young investigator who joined him on one of his more than 2,000 fire investigations. “Absolutely nothing” was the correct answer. Most of the time fire investigators find nonexistent patterns, Lentini elaborated, or they think a certain mark means the fire burned “fast” or “slow,” allegedly indicated by the “alligatoring” of wood: small, flat blisters mean the fire burned slow; large, shiny blisters mean it burned fast. Nonsense, he said. It may take a while for a fire to get going, but once a couch or bed burns and reaches a certain temperature, you are not going to be able to discern much about its cause.

Lentini debunked the myth of window “crazing” in which cracks indicate rapid heating supposedly caused by an accelerant (arson). In fact, the cracks are caused by rapid cooling, as when firefighters spray water on a burning building with windows. He also noted that burn marks on the floor are not the result of a liquid deliberately poured on it. When a fire consumes an entire room, the extreme heat burns even the floor, along with melting metal and leaving burn marks under a doorway threshold, which many investigators assume implies the use of an accelerant. “Most of the ‘science’ of fire and explosive analysis has been conducted by insurance companies looking to find evidence of arson so they don’t have to pay off their policies,” Lentini explained to me when I asked how his field became so fraught with pseudoscience.

Itiel Dror of the JDI Center for the Forensic Sciences at University College London spoke about his research on “cognitive forensics”— how cognitive biases affect forensic scientists. For example, the hindsight bias can lead one to work backward from a suspect to the evidence, and then the confirmation bias can direct one to find additional confirming evidence for that suspect even if none exists. Dror discussed studies that show “that the same expert examiner, evaluating the same prints but within different contexts, may reach different and contradictory decisions.” Not just fingerprints. Even DNA analysis is subjective. “When 17 North American expert DNA examiners were asked for their interpretation of data from an adjudicated criminal case in that jurisdiction, they produced inconsistent interpretations,” Dror and his co-author wrote in a 2011 paper in Science and Justice.

No one knows how many innocent people have been convicted based on junk forensic science, but the National Research Council report recommends substantial funding increases to enable labs to conduct experiments to improve the validity and reliability of the many forensic subfields. Along with a National Commission on Forensic Science, which was established in 2013, it’s a start.

August 1, 2015

The Meaning of Life in a Formula

Harvard University paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, who died in 2002, was a tough-minded skeptic who did not suffer fools gladly when it came to pseudoscience and superstition. Gould was a secular Jew who did not believe in God, but he had a soft spot for religion, expressed most famously in his principle of NOMA—nonoverlapping magisteria. The magisterium (domain of authority) of science “covers the empirical realm: what is the universe made of (fact) and why does it work this way (theory),” he wrote in his 1999 book Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life. “The magisterium of religion extends over questions of ultimate meaning and moral value.”

In part, Gould’s motivations were personal (he told me on many occasions how much respect he had for religion and for his many religious friends and colleagues). But in his book, he claimed that “NOMA represents a principled position on moral and intellectual grounds, not a merely diplomatic solution.” For NOMA to work, however, Gould insisted that just as “religion can no longer dictate the nature of factual conclusions residing properly within the magisterium of science, then scientists cannot claim higher insight into moral truth from any superior knowledge of the world’s empirical constitution.”

Initially I embraced NOMA because a peaceful concordat is usually more desirable than a bitter conflict (plus, Gould was a friend), but as I engaged in debates with theists over the years, I saw that they were continually trespassing onto our turf with truth claims on everything from the ages of rocks and miraculous healings to the reality of the afterlife and the revivification of a certain Jewish carpenter. Most believers hold the tenets of their religion to be literally (not metaphorically) true, and they reject NOMA in practice if not in theory—for the same reason many scientists do. In his 2015 penetrating analysis of Faith vs. Fact: Why Science and Religion are Incompatible, University of Chicago evolutionary biologist Jerry A. Coyne eviscerates NOMA as “simply an unsatisfying quarrel about labels that, unless you profess a watery deism, cannot reconcile science and religion.”

Curiously, however, Coyne then argues that NOMA holds for scientists when it comes to meaning and morals and that “by and large, scientists now avoid the ‘naturalistic fallacy’—the error of drawing moral lessons from observations of nature.” But if we are not going to use science to determine meaning and morals, then what should we use? If NOMA fails, then it must fail in both directions, thereby opening the door for us to experiment in finding scientific solutions for both morals and meaning.

In The Moral Arc: How Science and Reason Lead Humanity toward Truth, Justice, and Freedom, I give examples of how morality can be a branch of science, and in his 2014 book Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality without Religion, neuroscientist Sam Harris makes a compelling case that meaning can be found through the scientific study of how the mind works (particularly during meditation and other mindful tasks), noting that “nothing in this book needs to be accepted on faith.” And Martin Seligman’s pioneering efforts to develop a science of positive psychology have had as their aim a fuller understanding of the conditions and actions that make people happy and their lives meaningful.

Yet what if science shows that there is no meaning to our lives beyond the purposes we create, however lofty and noble? What if death is the end and there is no soul to continue after life? According to psychologists Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg and Tom Pyszczynski, in their 2015 book The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life, the knowledge that we are going to die has been a major driver of human affairs and social institutions. Religion, for example, is at least partially explained by what the authors call terror management theory, which posits that the conflict between our desire to live and our knowledge of our inevitable death creates terror, quelled by the promise of an afterlife. If science takes away humanity’s primary source of terror management, will existential anguish bring civilization to a halt? I think not. We do live on—through our genes, our loves, our friends and our contributions (however modest) to making the world a little bit better today than it was yesterday. Progress is real and meaningful, and we can all participate.

July 9, 2015

Michael Shermer on Reasonable Doubt at TEDxGhent

Michael Shermer explains how a scientific way of thinking manages to improve the world in various kinds of ways. He describes how science and reason lead humanity toward truth, justice and freedom. “As democracy increases, violence decreases” is the theme of his talk. He discusses the death penalty, women and gay rights and so much more. He states that within these delicate issues, rationality and abstract thinking are the keys to increased awareness and democracy.

Learn more about Michael Shermer’s book, The Moral Arc: How Science and Reason Lead Humanity toward Truth, Justice, and Freedom on the official website.

July 1, 2015

Outrageous

The ongoing rash of police using deadly force against minority citizens has triggered a search for a universal cause—most commonly identified as racism. Such soul searching is understandable, especially in light of the racist e-mails uncovered in the Ferguson, Mo., police department by the U.S. Department of Justice’s investigation into the death of 18-year-old Michael Brown.

To whatever extent prejudice still percolates in the minds of a few cops in a handful of pockets of American society (nothing like 50 years ago), it does not explain the many interactions between white police and minority citizens that unfold without incident every year or the thousands of cases of assaults on police that do not end in police deaths (49,851 in 2013, according to the FBI). What in the brains of cops or citizens leads either group to erupt in violence?

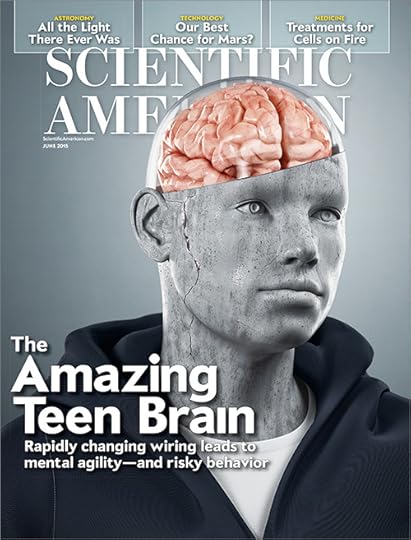

An answer may be found deep inside the brain, where a neural network stitches together three structures into what neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp calls the rage circuit: (1) the periaqueductal gray (it coordinates incoming stimuli and outgoing motor responses); (2) the hypothalamus (it regulates the release of adrenaline and testosterone as related to motivation and emotion); and (3) the amygdala (associated with automatic emotional responses, especially fear, it lights up in response to an angry face; patients with damage to this area have difficultly assessing emotions in others). When Panksepp electrically stimulated the rage circuit of a cat, it leaped toward his head with claws and fangs bared. Humans similarly stimulated reported feeling uncontrollable anger.

The rage circuit is surrounded and modulated by the cerebral cortex, particularly the orbitofrontal cortex, wherein decisions are made about how you should respond to a particular stimulus— whether to act impulsively or show restraint. In her 1998 book Guilty by Reason of Insanity, psychiatrist Dorothy Otnow Lewis notes that when a cat’s cortex is surgically detached from the lower areas of its brain, it responds to mildly annoying stimuli with ferocity and violence, not unlike a convicted killer improbably named Lucky, who had lesions between his cortical regions and the rest of his brain. Lewis suspects that Lucky’s lesions were responsible for his savage stabbing of a store clerk.

In healthy brains and under normal circumstances, cortical self-control usually trumps emotional impulses. In certain conditions that call for strong emotions, such as when you feel threatened with bodily injury or death, it is prudent for the rage circuit to override the cortex, as in a case of a woman named Susan described by evolutionary psychologist David M. Buss in his 2005 book The Murderer Next Door. As her cocaine-fueled abusive husband advanced on her with a hunting knife screaming, “Die, bitch!” Susan kneed him in the groin and grabbed the knife. What happened next is what sociologist Randall Collins calls a “forward panic”—an explosion of violence akin to the wartime massacres at Nanking and My Lai and the beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police officers. “I stabbed him in the head and I stabbed him in the neck and I stabbed him in the chest and I stabbed him in the stomach,” Susan testified at her murder trial, explaining the 193 stab wounds resulting from her uncontrollable urge to avenge her abuse. Such emotions evolved as an adaptation to threats, especially when there is not time to compute the odds of an outcome. Fear causes us to pull back and retreat from risks. Anger leads us to strike out and defend ourselves against predators or bullies.

A charitable explanation for why cops kill is that certain actions by suspects (running away, or resisting arrest, or reaching into the squad car to grab a gun) may trigger the rage circuit to fire with such intensity as to override all cortical selfcontrol. This may be especially the case if the officer is modified by training and experience to look for danger or biased by racial profiling leading to negative expectations of certain citizens’ behavior.

Future police training should include putting cops in threatening situations and giving them techniques for diffusing the outcome. In their 2011 book Willpower, Roy F. Baumeister and John Tierney describe methods for suppressing such impulses. In turn, citizens should remember that cops are working to protect us from threats to our security.

June 1, 2015

Scientia Humanitatis

In the late 20th century the humanities took a turn toward postmodern deconstruction and the belief that there is no objective reality to be discovered. To believe in such quaint notions as scientific progress was to be guilty of “scientism,” properly said with a snarl. In 1996 New York University physicist Alan Sokal punctured these pretensions with his now famous article “Transgressing the Boundaries: Toward a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity,” chockablock full of postmodern phrases and deconstructionist tropes interspersed with scientific jargon, which he subsequently admitted were nonsensical gibberish.

I subsequently gave up on the humanities but am now reconsidering my position after an encounter this past March with University of Amsterdam humanities professor Rens Bod during a European book tour for The Moral Arc. In our dialogue, Bod pointed out that my definition of science—a set of methods that describes and interprets observed or inferred phenomena, past or present, aimed at testing hypotheses and building theories—applies to such humanities fields as philology, art history, musicology, linguistics, archaeology, historiography and literary studies.

Indeed, I had forgotten the story he recounted of Italian philologist Lorenzo Valla, who in 1440 exposed the Latin document Donatio Constantini—the Donation of Constantine, which was used by the Catholic Church to legitimize its land grab of the Western Roman Empire—as a fake. “Valla used historical, linguistic and philological evidence, including counterfactual reasoning, to rebut the document,” Bod explained. “One of the strongest pieces of evidence he came up with was lexical and grammatical: Valla found words and constructions in the document that could not possibly have been used by anyone from the time of Emperor Constantine I, at the beginning of the fourth century a.d. The late Latin word Feudum, for example, referred to the feudal system. But this was a medieval invention, which did not exist before the seventh century a.d.” Valla’s methods were those of science, Bod emphasized: “He was skeptical, he was empirical, he drew a hypothesis, he was rational, he used very abstract reasoning (even counterfactual reasoning), he used textual phenomena as evidence, and he laid the foundations for one of the most successful theories: stemmatic philology, which can derive the original archetype text from extant copies (in fact, the much later DNA analysis was based on stemmatic philology).”

Inspired by Valla’s philological analysis of the Bible, Dutch humanist Erasmus employed these same empirical techniques to demonstrate that, for example, the concept of the Trinity did not appear in bibles before the 11th century. In 1606 Leiden University professor Joseph Justus Scaliger published a philological reconstruction of the ancient Egyptian dynasties, finding that the earliest one, dating to 5285 b.c., predated the Bible’s chronology for the creation of the world by nearly 1,300 years. This led later scholars such as Baruch Spinoza to reject the Bible as a reliable historical document. “Thus, abstract reasoning, rationality, empiricism and skepticism are not just virtues of science,” Bod concluded. “They had all been invented by the humanities.”

Why does this distinction matter? Because at a time when students and funding are fleeing humanities departments, the argument that they are at least good for “self-cultivation” misses their real value, which Bod has forcefully articulated in his recent book A New History of the Humanities (Oxford University Press, 2014). The transdisciplinary connection between the sciences and humanities is well captured in the German word Geisteswissenschaften, which means “human sciences.” This concept embraces everything humans do, including the scientific theories we generate about the natural world. “Too often humanities scholars believe that they are moving toward science when they use empirical methods,” Bod reflected. “They are wrong: humanities scholars using empirical methods are returning to their own historical roots in the studia humanitatis of the 15th century, when the empirical approach was first invented.”

Regardless of which university building scholars inhabit, we are all working toward the same goal of improving our understanding of the true nature of things, and that is the way of both the sciences and the humanities, a scientia humanitatis.

May 1, 2015

Terrorism as Self-Help Justice

[image error]

IN AN UNINTENTIONALLY HILARIOUS VIDEO CLIP, primatologist Frans de Waal narrates an experiment conducted in his laboratory at Emory University involving capuchin monkeys. One monkey exchanges a rock for a cucumber slice, which he gleefully ingests. But after seeing another monkey receive a much tastier grape for a rock, he angrily hurls it back at the experimenter when he is again offered a cucumber slice. He rattles the cage wall, slaps the floor and looks seriously peeved at this blatant injustice. (See the video at http://goo.gl/uTCILt.)

A sense of justice and injustice—right and wrong—is an evolved moral emotion to signal to others that if exchanges are not fair there will be a price to pay. How high a price? In the Ultimatum Game, in which one person is given a sum of money to divide with another person—with the stipulation that if the offer is accepted both keep the money, but if the offer is rejected no one gets any money—offers less than 30 percent of the sum are typically rejected. That is, we are willing to pay 30 percent to punish an offender. This is called moralistic punishment.

In a classic 1983 article entitled “Crime as Social Control,” sociologist Donald Black, now at the University of Virginia, notes that only about 10 percent of homicides are predatory in nature— murders that occur during a burglary or robbery. The other 90 percent are moralistic, a form of capital punishment in which the perpetrators are the judge, jury and executioner of a victim they perceive to have wronged them in some manner deserving of the death penalty. Black’s disturbing examples include a man who “killed his wife after she ‘dared’ him to do so during an argument,” a woman who “killed her husband during a quarrel in which the man struck her daughter,” a man who “killed his brother during a heated discussion about the latter’s sexual advances toward his younger sisters,” a woman who “killed her 21-year-old son because he had been ‘fooling around with homosexuals and drugs,’” and others “during altercations over the parking of an automobile.” Recall the murder of three Muslims in Chapel Hill, N.C., this past February, which at least partly involved a parking spot dispute.

After the Middle Ages, such morally motivated self-help justice was replaced for the most part by rationally motivated criminal justice. Black notes, however, that when people do not trust the state’s justice system or believe it to be biased against them—or when people live in weak states with corrupt governments or in effectively stateless societies—they take the law into their own hands. Terrorism is one such activity, the expression of which, Black argues in a 2004 article in Sociological Theory entitled “The Geometry of Terrorism,” is a form of self-help justice whose motives depend on the particular terrorist group. These have ranged from revolutionary Marxism in the 1970s to apocalyptic Islam today as practiced by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (known as ISIS or ISIL), which is not a state at all but a loose confederation of jihadists.

Many American liberals and media pundits have downplayed their religious motives, but as Black told me in an e-mail, “Muslim terrorists should be taken at their word that their movement is Islamic, anti-Christian, anti-Jewish, etc. We have their word as evidence, and in my view that is the proper basis on which to classify their movement. Would we have said that the violence used by Protestants and Catholics during the Protestant Reformation had nothing to do with religion? That would be absurd.”

No less absurd is the belief that jihadists are secular political agitators in religious cloak. As Graeme Wood writes in “What ISIS Really Wants,” his investigative piece in the March issue of the Atlantic, “much of what the group does looks nonsensical except in light of a sincere, carefully considered commitment to returning civilization to a seventh-century legal environment, and ultimately to bringing about the apocalypse.” Yes, ISIS has attracted the disaffected from around the world, but “the religion preached by its most ardent followers derives from coherent and even learned interpretations of Islam,” Wood concludes, adding that its theology “must be understood to be combatted.”

April 1, 2015

Paleo Diets, GMOs, and Food Taboos

IN 1980 I SUBJECTED MYSELF to a weeklong cleansing diet of water, cayenne pepper, lemon and honey, topped off with a 150-mile bicycle ride that left me puking on the side of the road. Neither this nor any of the other fad diets I tried in my bike-racing days to enhance performance seemed to work as well as the “see-food” diet one of my fellow cyclists was on: you see it, you eat it.

In its essence, the see-food diet was the first so-called Paleo diet, not today’s popular fad, premised on the false idea that there is a single set of natural foods—and a correct ratio of them—that our Paleolithic ancestors ate. Anthropologists have documented a wide variety of foods consumed by traditional peoples, from the Masai diet of mostly meat, milk and blood to New Guineans’ fare of yams, taro and sago. As for food ratios, according to a 2000 study entitled “Plant-Animal Subsistence Ratios and Macronutrient Energy Estimations in Worldwide Hunter-Gatherer Diets,” published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, the range for carbohydrates is 22 to 40 percent, for protein 19 to 56 percent, and for fat 23 to 58 percent.

And what constitutes “natural” anyway? Humans have been genetically modifying foods through selective breeding for more than 10,000 years. Were it not for these original genetically modified organisms—and today’s more engineered GMOs designed for resistance to pathogens and herbicides and for better nutrient profiles—the planet could sustain only a tiny fraction of its current population. Golden rice, for example, was modified to enhance vitamin A levels, in part, to help Third World children with nutritional deficiencies that have caused millions to go blind. As for health and safety concerns, according to A Decade of EU-Funded GMO Research, a 2010 report published by the European Commission:

The main conclusion to be drawn from the efforts of more than 130 research projects, covering a period of more than 25 years of research, and involving more than 500 independent research groups, is that biotechnology, and in particular GMOs, are not per se more risky than e.g. conventional plant breeding technologies.

So why are so many people in a near moral panic over GMOs? One explanation may be found in University of California, Los Angeles, anthropologist Alan Fiske’s four-factor relational model theory of how people and objects interact:

communal sharing (equality among people);

authority ranking (between superiors and subordinates);

equality matching (one-to-one exchange); and

market pricing (from barter to money).

Our Paleolithic ancestors lived in egalitarian bands in which food was mostly shared equally among members (communal sharing). As these bands and tribes coalesced into chiefdoms and states, unequal distribution of food and other resources became common (authority ranking) until the system shifted to market pricing.

Violations of these relations help to show how GMOs have come to be treated more like moral categories than biological entities. Roommates, for example, are expected to eat only their own food or to replace one another’s consumed items (equality matching), whereas spouses share without keeping tabs (communal sharing). If you invite friends to dinner, it would be disconcerting if they offered to pay for the meal, but if you dine at a restaurant, you are required to pay the bill and not summon the owner to your home for a comparable cuisine. All four relational models are grounded in our natural desire for fairness and reciprocity, and when there is a perceived violation, it creates a sense of injustice.

Given the importance of food for survival and flourishing, I suspect GMOs—especially in light of their association with large corporations such as Monsanto that operate on the market-pricing model—feel like an infringement of communal sharing and equality matching. Moreover, the elevation of “natural foods” to near-mythic status, coupled with the taboo many genetic-modification technologies are burdened with—remember when in vitro fertilization was considered unnatural?—makes GMOs feel like a desecration. It need not be so. GMOs are scientifically sound, nutritionally valuable and morally noble in helping humanity during a period of rising population. Until then, eat, drink and be merry.

March 1, 2015

Forging Doubt

doesn’t mean we know nothing

WHAT DO TOBACCO, food additives, chemical flame retardants and carbon emissions all have in common? The industries associated with them and their ill effects have been remarkably consistent and disturbingly effective at planting doubt in the mind of the public in the teeth of scientific evidence. Call it pseudoskepticism.

It began with the tobacco industry when scientific evidence began to mount that cigarettes cause lung cancer. A 1969 memo included this statement from an executive at the Brown & Williamson tobacco company: “Doubt is our product since it is the best means of competing with the ‘body of fact’ that exists in the minds of the general public.” In one example among many of how to create doubt, a Philip Morris tobacco executive told a congressional committee: “Anything can be considered harmful. Applesauce is harmful if you get too much of it.”

The tobacco model was subsequently mimicked by other industries. As Peter Sparber, a veteran tobacco lobbyist said, “If you can ‘do tobacco,’ you can do just about anything in public relations.” It was as if they were all working from the same playbook, employing such tactics as: deny the problem, minimize the problem, call for more evidence, shift the blame, cherry-pick the data, shoot the messenger, attack alternatives, hire industry friendly scientists, create front groups.

Documentary filmmaker Robert Kenner encountered this last strategy while shooting his 2008 film Food, Inc.. He has said that he “kept bumping into groups like the Center for Consumer Freedom that were doing everything in their power to keep us from knowing what’s in our food.” Kenner has called them “Orwellian” because such front groups sound like neutral nonprofit think tanks in search of scientific truth but are, in fact, funded by the for-profit industries associated with the problems they investigate.

Consider “Citizens for Fire Safety,” a front group created and financed in part by chemical and tobacco companies to address the problem of home fires started by cigarettes. Kenner found it while making his 2014 film Merchants of Doubt, based on the 2010 book of the same title by historians of science Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway. (I appear in an interview in the film.) To misdirect regulators and the public away from the link between cigarettes and home fires, the tobacco industry hired Peter Sparber to work with the National Association of State Fire Marshals to promote the use of chemical flame retardants in furniture. As another memo reads: “You have to fireproof the world around the cigarette.” Suddenly Americans’ furniture was awash in toxic chemicals.

Climate change is the latest arena for pseudoskepticism, and the front group du jour is ClimateDepot.com, financed in part by Chevron and Exxon and headed by a colorful character named Marc Morano, who told Kenner: “I’m not a scientist, but I do play one on TV occasionally … hell, more than occasionally.” Morano’s motto to challenge climate science, about which he admits he has no scientific training, is “keep it short, keep it simple, keep it funny.” That includes ridiculing climate scientists such as James E. Hansen of Columbia University. “You can’t be afraid of the absolute hand-to-hand combat metaphorically. And you’ve got to name names, and you’ve got to go after individuals,” he says, adding with a wry smile, “I think that’s what I enjoy the most.”

Manufacturing doubt is not difficult, because in science all conclusions are provisional, and skepticism is intrinsic to the process. But as Oreskes notes, “Just because we don’t know everything, that doesn’t mean we know nothing.” We know a lot, in fact, and it is what we know that some people don’t want us to know that is at the heart of the problem. What can we do about this pseudoskepticism?

Magicians have a saying, reiterated in Merchants of Doubt by close-up prestidigitator extraordinaire Jamy Ian Swiss: “Once revealed, never concealed.” He demonstrates it with a card trick in which a selected card that goes back into the deck ends up underneath a drinking glass on the table. It is virtually impossible to see how it is done, but once the move is highlighted in a second viewing, it is virtually impossible not to see it thereafter. The goal of proper skepticism is to reveal the secrets of dubious doubters so that the magic behind their tricks disappears.

February 1, 2015

A Moral Starting Point

Why is it wrong to enslave or torture other humans, or take their property, or discriminate against them? That these actions are wrong, almost no one disputes. But why are they wrong?

For an answer, most people turn to religion (because God says so), or to philosophy (because rights theory says so), or to political theory (because the social contract says so). In The Moral Arc, published in January, I show how science may also contribute an answer. My moral starting point is the survival and flourishing of sentient beings. By survival, I mean the instinct to live, and by flourishing, I mean having adequate sustenance, safety, shelter, and social relations for physical and mental health. By sentient, I mean emotive, perceptive, sensitive, responsive, conscious, and, especially, having the capacity to feel and to suffer. Instead of using criteria such as tool use, language, reasoning or intelligence, I go deeper into our evolved brains, toward these more basic emotive capacities. There is sound science behind this proposition.

According to the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness—a statement issued in 2012 by an international group of prominent cognitive and computational neuroscientists, neuropharmacologists and neuroanatomists—there is a continuity between humans and nonhuman animals, and sentience is the most important common characteristic. The neural pathways of emotions, for example, are not confined to higher-level cortical structures in the brain but are found in evolutionarily older subcortical regions. Artificially stimulating the same regions in human and nonhuman animal brains produces the same emotional reactions in both. Attentiveness, decision making, and the emotional capacity to feel and suffer are found across the branches of the evolutionary tree. This is what brings all humans and many nonhuman animals into our moral sphere.

The arc of the moral universe really is bending toward progress, by which I mean the improvement of the survival and flourishing of individual sentient beings. I emphasize the individual because that is who survives and flourishes, or who suffers and dies, not the group, tribe, race, gender, state or any other collective. Individual beings perceive, emote, respond, love, feel and suffer—not populations, races, genders or groups. Historically, abuses have been most rampant—and body counts have run the highest—when the individual is sacrificed for the good of the group. It happens when people are judged by the color of their skin, or by their gender, or by whom they prefer to sleep with, or by which political or religious group they belong to, or by any other distinguishing trait our species has identified to differentiate among members instead of by the content of their individual character.

The rights revolutions of the past three centuries have focused almost entirely on the freedom and autonomy of individuals, not collectives—on the rights of persons, not groups. Individuals vote, not genders. Individuals want to be treated equally, not races. In fact, most rights protect individuals from being discriminated against as individual members of a group, such as by race, creed, color, gender, and now sexual orientation and gender preference.

The singular and separate organism is to biology and society what the atom is to physics—a fundamental unit of nature. The first principle of the survival and flourishing of sentient beings is grounded in the biological fact that it is the discrete organism that is the main target of natural selection and social evolution, not the group. We are a social species, but we are first and foremost individuals within social groups and therefore ought not to be subservient to the collective.

This drive to survive is part of our essence, and therefore the freedom to pursue the fulfillment of that essence is a natural right, by which I mean it is universal and inalienable and thus not contingent only on the laws and customs of a particular culture or government. As a natural right, the personal autonomy of the individual gives us criteria by which we can judge actions as right or wrong: Do they increase or decrease the survival and flourishing of individual sentient beings? Slavery, torture, robbery and discrimination lead to a decrease in survival and flourishing, and thus they are wrong. QED.

January 1, 2015

Here Be Zombies

The 2014 premier of The Walking Dead—AMC’s postapocalyptic dystopian television series about zombies—was the most watched cable show in history. There have been a slew of popular zombie films such as Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead, Night of the Living Dead, 28 Days Later, I Am Legend and of course the perennial favorite Frankenstein. There is even a neuroscience text on the zombie brain, Do Zombies Dream of Undead Sheep? by Timothy Verstynen and Bradley Voytek (Princeton University Press, 2014), in which the authors consider real disorders that could turn the living into the living dead. Why are we so intrigued by zombies?

Zombies, for one thing, fit into the horror genre in which monstrous creatures—like dangerous predators in our ancestral environment— trigger physiological fight-or-flight reactions such as an increase in heart rate and blood pressure and the release of such stress hormones as cortisol and adrenaline that help us prepare for danger. New environments may contain an element of risk, but we must explore them to find new sources of food and mates. So danger contains an element of both fear and excitement.

We also have a fascination with liminal beings that fall in between categories, writes philosopher Stephen T. Asma in his 2009 book On Monsters (Oxford University Press). The fictional Frankenstein monster, like most zombies, is a being in between animate and inanimate, human and nonhuman. Hermaphrodites fall between male and female, and hybrid animals fall between species. Our innate templates for categorizing objects and beings are modified through experience, and when we encounter something or someone new, we check for category matches. Moderate deviation from the known category generates attention (friend or foe?), Asma says, but a “cognitive mismatch” elicits both dread and fascination. Add the emotion of disgust triggered by slime, drool, snot, blood, feces and rotting flesh, and we may find ourselves both repelled and drawn to such liminal creatures.

Distinguishing between zombies and nonzombies also hints at the deeper problem of xenophobia, which evolved as part of our nature to be suspicious of outsiders who, in our evolutionary past, were potentially dangerous. People from other groups, especially those perceived to be a threat, are moved into other cognitive categories and relabeled as mongrels, pests, vermin, rats, lice, maggots, cockroaches and parasites—all the easier to destroy them. Such labels are inevitably applied to new out-groups moving into the territory of an established in-group or conflicting economically or culturally with one—blacks moving into white neighborhoods, Jews establishing businesses in gentile-dominated markets, the Hutus resenting the dominant Tutsis in Rwanda. Fundamentalist Muslims do not “hate our freedoms” (as President George W. Bush conjectured). Instead, as Asma notes, they created a uniquely American monster in which “we are seen as godless, consumerist zombies, soulless hedonists without honor, family, or purpose.”

On our cognitive maps are areas labeled “Here Be Monsters,” where we put outsiders perceived to be dangerous. Fortunately, we have learned to curb such chauvinisms. As a result, the moral sphere has expanded to include all racial and ethnic groups as worthy of respect and equality, in principle if not always in practice. We have done so, in part, by overriding our instinctive impulses through reason, allowing us to take the perspective of another. Shakespeare worked out the logic in The Merchant of Venice when he has Shylock ask:

Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal’d by the same means, warm’d and cool’d by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? A

nd if you wrong us, do we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that.

Perhaps zombies and other fictional beings stimulate those neural regions of our nonzombie brains that allow for a healthy and nonviolent outlet for such ancient callings.

Michael Shermer's Blog

- Michael Shermer's profile

- 1155 followers