Michael Shermer's Blog, page 4

May 1, 2017

On Witches and Terrorists

As recounted by author and journalist Daniel P. Mannix, during the European witch craze the Duke of Brunswick in Germany invited two Jesuit scholars to oversee the Inquisition’s use of torture to extract information from accused witches. “The Inquisitors are doing their duty. They are arresting only people who have been implicated by the confession of other witches,” the Jesuits re ported. The duke was skeptical. Suspecting that people will say anything to stop the pain, he invited the Jesuits to join him at the local dungeon to witness a woman being stretched on a rack. “Now, woman, you are a confessed witch,” he began. “I suspect these two men of being warlocks. What do you say? Another turn of the rack, executioners.” The Jesuits couldn’t believe what they heard next. “No, no!” the woman groaned. “You are quite right. I have often seen them at the Sabbat. They can turn themselves into goats, wolves and other animals…. Several witches have had children by them. One woman even had eight children whom these men fathered. The children had heads like toads and legs like spiders.” Turning to the flabbergasted Jesuits, the duke inquired, “Shall I put you to the torture until you confess?”

One of these Jesuits was Friedrich Spee, who responded to this poignant experiment on the psychology of torture by publishing a book in 1631 entitled Cautio Criminalis, which played a role in bringing about the end of the witch mania and demonstrating why torture as a tool to obtain useful information doesn’t work. This is why, in addition to its inhumane elements, it is banned in all Western nations, including the U.S., whose Eighth Amendment of the Constitution prohibits “cruel and unusual punishments.”

What about waterboarding? That’s “enhanced interrogation,” not torture, right? When the late journalist Christopher Hitchens underwent waterboarding for one of his Vanity Fair columns, he was forewarned (in a document he had to sign) that he might “receive serious and permanent (physical, emotional and psychological) injuries and even death, including injuries and death due to the respiratory and neurological systems of the body.” Even though Hitchens was a hawk on terrorism, he nonetheless concluded: “If waterboarding does not constitute torture, then there is no such thing as torture.”

Still, what if there’s a “ticking time bomb” set to detonate in a major city, and we have the terrorist who knows where it is— wouldn’t it be moral to torture him to extract that information? Surely the suffering or death of one to save millions is justified, no? Call this the Jack Bauer theory of torture. In the hit television series 24, Kiefer Sutherland’s character is a badass counterterrorism agent whose “ends justify the means” philosophy makes him a modern-day Tomás de Torquemada. In most such scenarios, Bauer (and we the audience) knows that he has in his clutches the terrorist who has accurate information about where and when the next attack is going to occur and that by applying just the right amount of pain, he will extort the correct intelligence just in time to avert disaster. It’s a Hollywood fantasy. In reality, the person in captivity may or may not be a terrorist, may or may not have accurate information about a terrorist attack, and may or may not cough up useful intelligence, particularly if his or her motivation is to terminate the torture.

In contrast, a 2014 study in the journal Applied Cognitive Psychology entitled “The Who, What, and Why of Human Intelligence Gathering” surveyed 152 interrogators and found that “rapport and relationship-building techniques were employed most often and perceived as the most effective regardless of context and intended outcome, particularly in comparison to confrontational techniques.” Another 2014 study in the same journal— “In terviewing High Value Detainees”—sampled 64 practitioners and detainees and found that “detainees were more likely to disclose meaningful information … and earlier in the interview when rapport-building techniques were used.”

Finally, an exhaustive 2014 report by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence analyzed millions of internal CIA documents related to the torture of terrorism suspects, concluding that “the CIA’s use of its enhanced interrogation techniques was not an effective means of acquiring intelligence or gaining cooperation from detainees.” It adds that “multiple CIA detainees fabricated information, resulting in faulty intelligence.” Terrorists are real. Witches are not. But real or imagined, torture doesn’t work.

April 21, 2017

Science Makes America Great

Dear President Trump:

Fifty-five years ago this week President John F. Kennedy hosted a dinner honoring Nobel Prize laureate scientists, remarking:

I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.

In fact, Kennedy added, the author of the Declaration of Independence and 3rd President of the United States could “could calculate an eclipse, survey an estate, tie an artery, plan an edifice, try a cause, break a horse, and dance the minuet.”

From the earliest days of our nation, science as been at the forefront of what makes America great. Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, Benjamin Franklin, James Madison, John Adams and many of the other founding fathers were either practicing scientists or were trained in the sciences. They deliberately adapted the scientific method of gathering data, running experiments, and testing hypotheses to their construction of our nation. Their understanding of the provisional nature of findings led them to develop a political system in which doubt and disputation were the centerpieces of a functional polity.

They thought of political governance as a problem solving technology rather than as a power grabbing opportunity. They thought of democracy in the same way that they thought of science—as a method, not an ideology. They argued, in essence, that no one knows how to govern a nation so we have to set up a system that allows for experimentation. Try this. Try that. Check the results. Rinse and Repeat. That is the heart of science.

For example, there are 50 different states, each with its own constitution and set of laws. These are 50 different experiments. For example, every state has different gun control laws, so we can treat these as experiments from which we can gather results and draw conclusions: states with more guns and fewer controls have higher homicide and suicide rates.

Every time an amendment to the Constitution is ratified and enacted into law, that is an experiment. The 19th Amendment that granted women the right to vote in 1920 worked, so we still abide by it. By contrast, the 18th Amendment passed in 1919 that prohibited alcohol to test the hypothesis that it would reduce drinking and crime failed, so in 1933 the 21st Amendment was enacted, overturning it. Changing your mind when the evidence changes is a virtue, not a vice.

The centuries long experiment of using torture and the death penalty to deter crime also failed, so most states abandoned the practice in favor of other methods that work.

These are not controlled laboratory experiments like physicists and biologists run, but they are real-world experiments whose results are nevertheless valuable to social scientists, policy makers, and the public.

For example, policy experiments showed that teaching abstinence in sex education classes does not stop teens from having sex, and criminalizing abortions did not curb the practice. In both cases, information and contraception works better.

Foreign policy decisions are also experiments. For example, the United States intervention in Germany in 1941 was an experiment that very likely prevented the deaths of millions of people. The United States not intervening in Rwanda in 1994 was an experiment that very likely resulted in many more deaths. The United States intervention in Iraq appears to have been a failed experiment, whereas the result of today’s experiment of intervening in Syria is unknown. Sometimes science can be very complicated and its results difficult to interpret.

Communism was a century-long experiment that failed, as measured by the deaths of tens of millions of its own citizens. The division of North and South Korea over half a century ago was an experiment whose results we can see from space: one is dark and impoverished while the other is bright and flourishing. We can learn from such experiments, which is why Thomas Jefferson called democracy an experiment, as when he wrote in 1804:

No experiment can be more interesting than that we are now trying, and which we trust will end in establishing the fact, that man may be governed by reason and truth.

One of the hallmarks of science is its openness to criticism and the freedom to challenge any and all ideas. That is why our founding fathers also insisted on free speech and a free press, because this daring new political experiment depended on unconditional open access to knowledge and the freedom of its citizens to see and to think for themselves.

President Trump, I urge you to consider the words of a great American who helped to make our nation the most powerful on earth. J. Robert Oppenheimer was the head of the atomic-bomb building Manhattan Project, and in 1949 he proclaimed:

There must be no barriers to freedom of inquiry. There is no place for dogma in science. The scientist is free, and must be free to ask any question, to doubt any assertion, to seek for any evidence, to correct any errors. Our political life is also predicated on openness. We know that the only way to avoid error is to detect it and that the only way to detect it is to be free to inquire. And we know that as long as men are free to ask what they must, free to say what they think, free to think what they will, freedom can never be lost, and science can never regress.

April 14, 2017

How Might a Scientist Think about the Resurrection?

IMAGE ABOVE: The Bruder Klaus Field Chapel, Mechernich, Germany (near Köln), built 2005–2007 following the plans of the Swiss architect Peter Zumthor. Photograph by Michael Shermer

For the world’s two billion Christians, Easter marks the resurrection of Jesus after his crucifixion death at the hands of the Romans. It is the resurrection that sets Christians apart from all other religions. In fact, as denoted in 1 Corinthians 15: 13–14: “But if there is no resurrection of the dead, then not even Christ has been raised. And if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain.”

Did Jesus die and come back to life? In the parlance of current events, is this a fake news story, an alternative fact invented by the followers of Jesus, or did it really happen?

As a scientist who was once a born-again evangelical Christian I have given this question much thought. Although I am no longer a religious believer, I think there is reasonable evidence that a man named Jesus probably did exist, and that there are good reasons to believe he was crucified by the Romans, which was a common tool of capital punishment at the time, employed against even common thieves, such as the two men crucified on either side of Jesus. Whether or not Jesus “died for our sins” is a pure theological dogma untestable by science, but the matter of his resurrection is open to scrutiny. There are reasons to doubt the claim.

First, Jews and Muslims, along with the world’s other four billion religious people, do not believe in the resurrection of Jesus. This is especially noteworthy in the other Abrahamic religions, given that Jews and Muslims worship the same God. And although the veracity of a truth claim is not determined by majority rule, if there were compelling evidence for this all-important event wouldn’t it at least convince some in a few other religions? That Jewish Rabbis and Muslim Clerics are so well educated and professionally trained in the art of evaluating arguments and evidence speaks volumes to their skepticism of the resurrection.

Second, resurrecting someone back to life who was truly dead would be one of the most unusual events to ever happen in history, given the fact that to date approximately 100 billion people have lived and died before us and not one of them has returned to life. So the resurrection would be a one in a hundred billion event, beyond miraculous by our normal conception of that word. And yet the evidence for it is far less than the most commonplace events of that time, such as Roman wars and conquests.

Third, the scientific principle of proportionality means we should adjust our confidence in a truth claim according to the proportion of evidence for it, and the more extraordinary the claim the more extraordinary the evidence for it must be. The evidence for the assassination of Julius Caesar, for example, is extensive, even though political assassinations have been commonplace throughout history. The resurrection of Jesus is far more extraordinary, and yet proportionally the evidence for it is far less.

Fourth, there are no reliable extra-biblical sources documenting Jesus’s resurrection, which is surely something Roman scribes would have noted, given the extensive written records we have of a wide range of Roman events, from the mundane affairs of daily life to the consequential affairs of political leaders.

Fifth, the biblical sources we have for the resurrection are not dependable. The gospels were written many decades after Jesus’ death, and we know how unreliable human memory is for even recent events, much less those decades in the past. Perhaps the eyewitnesses saw or heard what they wanted or were expecting to see and hear. Such post-death apparitions are not uncommon among people who have lost a loved one. Maybe the story was exaggerated over multiple retellings, which is another commonplace phenomena. Perhaps the gospel authors added miraculous elements to real events in order to make them more divinely inspired and thus to elevate their religious beliefs to a higher status.

Sixth, even the Catholic Church—home to one billion of the world’s two billion Christians—states in its Catechism: “Although the Resurrection was an historical event that could be verified by the sign of the empty tomb and by the reality of the apostles’ encounters with the risen Christ, still it remains at the very heart of the mystery of faith as something that transcends and surpasses history.”

Ultimately, any claim that transcends and surpasses history means that science cannot, even in principle, prove or disprove it. If that is the case, then the resurrection is not a truth claim at all, but an article of faith belonging to one religion among hundreds, and with no means of determining if it is a fact or an alternative fact. In that case skepticism is warranted.

April 11, 2017

If There is No God, is Murder Wrong?

On the popular online site Prager University, the conservative radio talk show host Dennis Prager recently posted the video “If there is no God, Murder Isn’t Wrong.”

Nearly two million people have heard his argument that without God, anything goes.

I’ve known Dennis for many years and have been a guest on his show a number of times. He’s a smart guy, and we agree on many issues, but on this one I think he is wrong.

Prager’s belief that without God there can be no objective morality is, in fact, a common one many people hold. It’s wrong for 4 reasons.

1. Divine Command Theory is Fallible

The argument that our morals come from God is what philosophers and theologians call Divine Command Theory, well captured by the popular bumper sticker:

God said it. I believe it. That settles it.

This argument was refuted 2500 years ago by the Greek philosopher Plato, when he asked, in so many words:

“Is what is morally right or wrong commanded by God because it is inherently right or wrong, or is it morally right or wrong only because it is commanded by God?”

For example, if murder is wrong because God said it is wrong, what if He said it was okay? Would that make murder right? Of course not!

If God commanded murder wrong for good reasons, what are those reasons and why can’t we base our proscription against murder on those reasons alone and skip the divine middleman?

In other words, if murder is really wrong in the moral universe, then it doesn’t matter what God thinks, or if there’s a god or not, it’s still wrong.

2. The Either-Or Fallacy

We are being told that we have to choose between a God-based Absolute Morality where there are clear distinctions between right and wrong, and a Godless Relative Morality where right and wrong are just opinions.

This is what philosophers call the Either-Or Fallacy, or the Fallacy of False Alternatives. It’s a classic debate tactic in which you argue that if my opponent’s position is wrong, then my position is right. It’s called a fallacy because (1) you have to actually prove your own position, not just disprove the other person’s opinion, and (2) there may be third choice.

In fact, between Absolute Morality and Relative Morality is what I call Provisional Morality, or moral values that are true for most people in most circumstances most of the time.

All societies throughout history and around the world today, for example, have sanctions against murder. Why? Because if there were no proscription against murder no social group could survive, much less flourish. All social order would break down. We can’t have people running around killing each other willy nilly.

That said, there are exceptions to the rule that murder is wrong, even here in the Judeo-Christian west. Murder in self-defense is an example for individuals. Capital Punishment murder is an example for states. Just War murder is an example for nations.

But the fact that there are exceptions to the sanction against murder does not gainsay the provisional moral truth that murder is wrong.

3. The Religious Source of Morality is Unreliable

Divine Command Theory implies that people get their morality from God. But how? Most people don’t see burning bushes, hear the voice of God, or receive chiseled stone tablets from the almighty. So where do these ideas about right and wrong come from?

Most religious people say that they get their morality from their Holy Book. The problem with this is that God apparently dictated different moral commands for different religions, so which one is right? Each makes absolute moral truth claims that contradict one another. They can’t all be right.

Even within the Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, there is much disagreement about right and wrong. Members of these religions still commit violence in the name of God today—because religion has no method by which to determine right from wrong. It’s religion that gives us moral opinions, but science actually has a systematic method for determining truth claims.

Which brings me to my fourth and final point…

4. Absolute Morality Corrupts Absolutely

The belief in Absolute Morality inexorably leads to the conclusion that anyone who believes differently has departed from this truth and thus is unprotected by our moral obligations.

Historically this Absolutism led to crusades, inquisitions, witch hunts, religious wars, and genocides—all in the name of God. Today, it’s why suicide bombers shout out Allahu Akbar—God is Great.

These Islamic terrorists also believe in Absolute God-Given Moral Values of Right and Wrong, and they act accordingly.

What about Hitler, Stalin and Mao? Aren’t they examples of what atheism and Godless Moral Relativism leads to, as Prager says? No.

First, Hitler was not an atheist. He was a Catholic. And Stalin was Orthodox.

But all this is irrelevant because they killed in the name of ideology, not atheism, which isn’t even a belief system.

In fact, National Socialism and Communism were faux religions in those societies, and as such they provided their believers with Absolute Moral Values about Right and Wrong. And they serve as examples of why Absolute Morality Corrupts Absolutely.

Morality is not absolute. But neither is it relative. Where does it come from?

We get our morality from our parents, peers, mentors, teachers, books, and culture, and we listen to that still small voice within—our moral conscience. Morality is in our nature. We are moral beings, with real moral emotions that we can reason about, which we have doing for centuries.

Ever since the Enlightenment, religious-based theocracies have been replaced with Constitution-based democracies, and the result was the abolition of slavery and torture, the democratic rule of law, the decline of violence, and the granting of civil rights, women’s rights, children’s rights, gay rights, and animal rights, as our moral sphere has expanded ever larger.

As I documented in my book The Moral Arc, there is a real moral universe with real moral values about right and wrong, and there is an arc to that moral universe that really does bend towards truth, justice, and freedom. It’s up to us to make that happen.

April 7, 2017

Interview with Jayde Lovell of SciQ

Jayde Lovell is the host of SciQ on TYT.

April 1, 2017

What is Truth, Anyway?

According to the Oxford English Dictionary’ s first definition, a “skeptic” is “one who holds that there are no adequate grounds for certainty as to the truth of any proposition whatever.” This is too nihilistic. There are many propositions for which we have adequate grounds for certainty as to their truth:

There are 84 pages in this issue of Scientific American. True by observation.

Dinosaurs went extinct around 65 million years ago. True by verification and replication of radiometric dating techniques for volcanic eruptions above and below dinosaur fossils.

The universe began with a big bang. True by a convergence of evidence from a wide range of phenomena, such as the cosmic microwave background, the abundance of light elements (such as hydrogen and helium), the distribution of galaxies, the large-scale structure of the cosmos, the redshift of most galaxies and the expansion of space.

These propositions are “true” in the sense that the evidence is so substantial that it would be unreasonable to withhold one’s provisional assent. It is not impossible that the dinosaurs died a few thousand years ago (with the universe itself having been created 10,000 years ago), as Young Earth creationists believe, but it is so unlikely we need not waste our time considering it.

Then there are negative truths, such as the null hypothesis in science, which asserts that particular associations do not exist unless proved otherwise. For example, it is telling that among the tens of thousands of government e-mails, documents and files leaked in recent years, there is not one indication of a UFO cover-up or faked moon landing or allegation that 9/11 was an inside job by the Bush administration. Here the absence of evidence is evidence of absence.

Other propositions are true by internal validation only: dark chocolate is better than milk chocolate; Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” is the greatest rock song; the meaning of life hinges on the number 42. These types of truth are purely personal and thus unverifiable by others. In science, we need external validation.

What about religious truths? The proposition that Jesus was crucified may be true by historical validation, inasmuch as a man whom we refer to as Jesus of Nazareth probably existed, the Romans routinely crucified people for even petty crimes, and most biblical scholars—even those who are atheists or agnostics, such as renowned religious studies professor Bart Ehrman of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill—assent to this fact. The proposition that Jesus died for our sins, in contrast, is a faithbased claim with no purchase on valid knowledge. In between these is Jesus’s Resurrection, which is not impossible but would be a miracle if it were true. Is it?

The absence of evidence is evidence of absence.

The principle of proportionality demands extraordinary evidence for extraordinary claims. Of the approximately 100 billion people who have lived before us, all have died and none have returned, so the claim that one (or more) of them rose from the dead is about as extraordinary as one will ever find. Is the evidence commensurate with the conviction? According to philosopher Larry Shapiro of the University of Wisconsin–Madison in his 2016 book The Miracle Myth (Columbia University Press), “evidence for the resurrection is nowhere near as complete or convincing as the evidence on which historians rely to justify belief in other historical events such as the destruction of Pompeii.” Because miracles are far less probable than ordinary historical occurrences, such as volcanic eruptions, “the evidence necessary to justify beliefs about them must be many times better than that which would justify our beliefs in run-of-the-mill historical events. But it isn’t.”

What about the eyewitnesses? Maybe they “were superstitious or credulous” and saw what they wanted to see, Shapiro suggests. “Maybe they reported only feeling Jesus ‘in spirit,’ and over the decades their testimony was altered to suggest that they saw Jesus in the flesh. Maybe accounts of the resurrection never appeared in the original gospels and were added in later centuries. Any of these explanations for the gospel descriptions of Jesus’s resurrection are far more likely than the possibility that Jesus actually returned to life after being dead for three days.” The principle of proportionality also means we should prefer the more probable explanation over less probable ones, which these alternatives surely are.

Perhaps this is why Jesus was silent when Pontius Pilate asked him (John 18:38), “What is truth?”

March 28, 2017

Science for All

On 22 March, 2017 I posted on my Twitter account (@michaelshermer) a link to this article titled “Science march on Washington, billed as historic, plagued by organizational turmoil,” which chronicled the “infighting among organizers, attacks from outside scientists who don’t feel their interests are fairly represented, and operational disputes.” The article went on to note that “Tensions have become so pronounced that some organizers have quit and many scientists have pledged not to attend.” Predictably, politics was the divisive element, most notably identity politics involving the proper representation of race and gender diversity, and immigration, obviously in response to the election of Donald Trump. The website of the march felt the need to post an official diversity policy that reads, in part, “We acknowledge that society and scientific institutions often fail to include and value the contributions of scientists from underrepresented groups.”

My initial thought was this: So let me get this straight. As the Federal government prepares to cut science budgets across the board, and in an era of fake news and alternative facts, instead of marching to proclaim how important science is to the American economy, not to mention human survival and flourishing, along with our commitment to facts and reason, you want to send a message to the public in general and the Trump administration in particular that science—the most universal institution in human history—is a failure when it comes to diversity and inclusion?

But then I realized that this had nothing to do with the ideals of science, which I articulated in a tweet posted shortly after the link to the article:

Science is universal, international, inclusive, nonpartisan, a-political, a-gender, a-race, & a-ideological. Don't inject identity politics.

— Michael Shermer (@michaelshermer) March 23, 2017

Although clearly this tweet seemed to resonate with many (over 4000 in fact), it also brought down upon my head a heap of hate. Many couldn’t see the point I was making: that a public march celebrating science is probably not the best place to engage in an in-depth history of science and its shortcomings when it comes to women and minorities, which are well documented and against which much progress has been made the past half century. You can see the tweet, and its responses. Typical of critical replies were these:

@michaelshermer if that were true, hiring, promotion, tenure, citation, publication, conferences would mirror population demographics (1/3)

— Meredith Schwartz (@Kalendaries) March 23, 2017

Have you considered how science played a role in the development of nukes, bombs, military tech, eugenics, genocide & so on? @michaelshermer

— feral fawcett (@nixnutzich) March 23, 2017

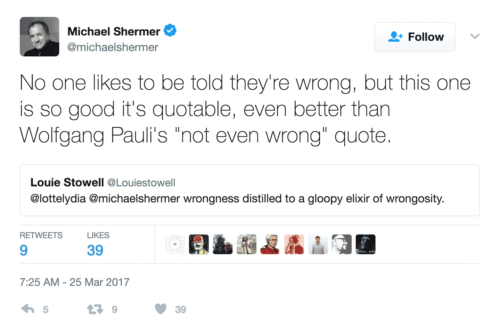

And my favorite, which I liked so much I retweeted it:

I tried to explain that I was tweeting about an ideal we should strive for (and for which science is particularly well positioned to implement), not a 140-character history of science.

I thought March for Science is to affirm our commitment to facts in the face of fake news & alternative facts, not social justice politics.

— Michael Shermer (@michaelshermer) March 23, 2017

I was promptly reminded of Hiroshima, Tuskegee, eugenics, etc., along with the documented biases against women and minorities in the past, to which I replied:

If you want to make it the March for Social Justice in Science that's a different theme than a march for commitment to facts & evidence.

— Michael Shermer (@michaelshermer) March 23, 2017

And this one in particular seemed to trigger emotions in a lot of readers:

As for my tweet science = universal, inclusive etc., there is just "Physics" not "Feminine Physics" "Transgender Physics" "Gay Physics" etc.

— Michael Shermer (@michaelshermer) March 23, 2017

Yesterday I hosted the theoretical physicist and popular science writer Lawrence Krauss for our Science Salon series and we were asked our thoughts on the March for Science by an audience member who had been following the Twitter-Storm over my tweet. Given that Krauss has worked in academia his entire career, including being involved in the hiring process of physicists, I asked him why people seem to think that science still excludes women and minorities (and others) when, in fact, it is peopled by professors who are almost entirely liberals who fully embrace the principles of inclusion (and the laws regarding affirmative action). Are we to believe that all these liberal academics, when behind closed doors, privately believe that women and minorities can’t cut it in science and so they continue to mostly hire only white men?

Krauss was unequivocal in his response. Absolutely not. There has never been a better time to be a woman in science, he explained, elaborating that at his university, Arizona State University, not only does the student body perfectly reflect the demographics of the state of Arizona, the President of ASU has mandated that if two candidates are equally qualified for a professorship, one a man and the other a woman, the woman should be selected for the job. Full stop.

This is not to say that there is perfect demographic parity in all of the sciences. There is not for a host of reasons, not the least of which is that equal opportunity for all is the goal, not perfect political identity (if that were the case then there should be affirmative action for conservatives, who are today among the least represented on college campuses). What we have been doing since the 1960s is to correct the biases of the past and open the doors to more people in more fields. To deny that there has been moral progress in this area is to deny the magnificent work of the civil rights, women’s rights, and gay rights activists of the past half century, as if their efforts counted for nothing. I wrote a book about how this happened, its title inspired as it was by the greatest of civil rights champions Martin Luther King Jr., but the story is not over. We have a long way to go but we’ve come a long way, thanks in large part to science and reason, so if there is something that I plan to march for on April 22 it is that fact, which is not an alternative fact but a real one.

March 27, 2017

Dying To Go To Heaven

This op-ed appeared on HuffingtonPost.com on March 24, 2017.

It was 20 years ago this week, March 20-26, 1997, that 39 members of the Heaven’s Gate cult “graduated” from this life to ascend to the UFO mothership that they believed would take them to an extraterrestrial paradise. I’ll never forget it. I was on book tour for Why People Believe Weird Things, and neither I nor any of my peers who study belief systems had ever heard of the cult. It was hard to fathom. Now, as I look back 20 years later, I believe the mass suicide has a deeper lesson that goes far beyond the confines of New Age fringe cults, and has relevance to understanding the motivations of today’s suicide terrorists.

An image of Marshall Applewhite during a video broadcast produced by Heaven’s Gate (religious group)

But first, let’s revisit the story. Heaven’s Gate was founded in 1975 by Marshall Applewhite and Bonnie Nettles after they met in a psychiatric hospital. They fell in love and believed their pairing had been foretold by extraterrestrials. In the 1980s and 1990s, they recruited several hundred followers, many of whom sold their possessions and lived in isolation, disconnected from their family and friends. They practiced living in dark rooms to simulate space travel and considered sex sinful, with six male members voluntarily undergoing castration.

In early 1997, the appearance of Comet Hale-Bopp foretold to them that the coming of the UFO mothership, said to be hiding behind the comet, that would take them to what they called The Evolutionary Level Above Human (TELAH), where they would live forever in unadulterated ecstasy. This story was reinforced by Art Bell, on his popular late-night radio show Coast to Coast AM, a purveyor of conspiratorial “alternative facts” (before they were known as such). Compared to eternal bliss in this extraterrestrial heaven, life on Earth was but a temporary stage in evolution. The transition was made in three waves that week, as members drank a deadly cocktail of phenobarbital, applesauce, and vodka; also pulling plastic bags over their heads for self-asphyxiation. Authorities found them all dead in a San Diego home on March 26. The event became a media circus. […]

March 20, 2017

Michael Shermer Sizzle Reel

See clips from Dr. Michael Shermer’s most noted media appearances including: twice on the Colbert Report, Larry King Live with UFOlogists, CNN, and other news shows debating creationists and Intelligent Design advocates, and other highlights from his 25 year career as a public intellectual.

4 reasons why people ignore facts and believe fake news

This op-ed appeared on BusinessInsider.com on March 18, 2017.

The new year has brought us the apparently new phenomena of fake news and alternative facts, in which black is white, up is down, and reality is up for grabs.

The inauguration crowds were the largest ever. No, that was not a “falsehood,” proclaimed by Kellyanne Conway as she defended Sean Spicer’s inauguration attendance numbers: “our press secretary…gave alternative facts to that.”

George Orwell, in fact, was the first to identify this problem in his classic Politics and the English Language (1946). In the essay, Orwell explained that political language “is designed to make lies sound truthful” and consists largely of “euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness.”

But if fake news and alternative facts is not a new phenomenon, and popular writers like Orwell identified the problem long ago, why do people still believe them? Well, there are several factors at work.

Michael Shermer's Blog

- Michael Shermer's profile

- 1155 followers