Michael Shermer's Blog, page 13

July 3, 2012

How to Learn to Think Like a Scientist (Without Being a Geek)

On March 31, 2011, I debated Deepak Chopra at Chapman University on “The Nature of Reality” that also featured Stuart Hameroff, Leonard Mlodinow, and several other commentators, all choreographed by the Chancellor of Chapman University, mathematician Daniele Struppa. In the greenroom before the debate Dr. Struppa was reviewing my bio and noted that I am an adjunct professor at Claremont Graduate University and made a comment that I should be an adjunct professor at Chapman as well. I said something like “sure, why not?” and when he introduced me on stage he said something about how I might also one day teach there. Daniele said I could teach anything I want as part of their Freshman Foundations Courses, so I suggested a course on Skepticism 101, or how to think like a scientist (without being a geek). I taught it the Fall semester of 2011 to 35 incoming Freshman students and it was a blast.

During the semester I hatched the idea that since the Skeptics Society is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit educational organization specializing in science education, that we should organize all the course materials that professors and teachers around the world are already utilizing. That is, as I was developing my own course materials I remembered all the requests we had received over the years at the Skeptics Society from educators to reprint articles from Skeptic magazine or use videos of our Distinguished Science Lecture Series at Caltech. There are, in fact, hundreds and hundreds (maybe thousands) of such courses that go under various names that involve skepticism, science and pseudoscience, science and the paranormal, psychology and parapsychology, the psychology of belief, the history of science, the philosophy of science, science studies, critical thinking, and the like. As I went digging through our own webpage Skeptic.com and surfed the Net for other teacher’s webpages in search of good teaching materials, we thought it might be good to invite people to submit their course syllabi, lectures, Powerpoint and Keynote presentations, videos, student projects, reading lists, and the like, which we just launched last week.

EXPLORE THE SKEPTICISM 101 RESOURCE CENTER

Thanks to the support of my good friend Tyson Jacobsen I was able to hire an outstanding graduate student, Anondah Saide, to organize the Skepticism 101 program for us, which began with her TAing the Skepticism 101 course at Chapman University. Anondah was one of my graduate students at Claremont Graduate University who conducts research into the sociology of pseudoscience and the paranormal, and she has a deep interest in education and how to teach students to think critically about the paranormal and the supernatural, so she was a perfect fit for the class and this program.

The premise of the course is that we have a serious problem: we live in the Age of Science and yet pseudoscience and the paranormal are believed by far too many people still. Yes, it is better than it was 500 years ago when nearly everyone believed nonsense, but these figures from a 2009 Harris Poll of 2,303 adult Americans, who were asked to “Please indicate for each one if you believe in it, or not”:

82% believe in God

76% believe in miracles

75% believe in Heaven

73% believe in Jesus is God

or the Son of God

72% believe in angels

71% believe in survival

of the soul after death

70% believe in the

resurrection of Jesus Christ

61% believe in hell

61% believe in

the virgin birth (of Jesus)

60% believe in the devil

45% believe in Darwin’s

Theory of Evolution

42% believe in ghosts

40% believe in creationism

32% believe in UFOs

26% believe in astrology

23% believe in witches

20% believe in reincarnation

Yikes! More people believe in angels and the devil than believe in the theory of evolution. And yet, such results match similar survey findings for belief in the paranormal conducted over the past several decades, including internationally. For example, a 2006 Readers Digest survey of 1,006 adult Britons reported that 43 percent said that they can read other people’s thoughts or have their thoughts read, more than half said that they have had a dream or premonition of an event that then occurred, more than two-thirds said they could feel when someone was looking at them, 26 percent said they had sensed when a loved-one was ill or in trouble, and 62 percent said that they could tell who was calling before they picked up the phone. A fifth said they had seen a ghost and nearly a third said they believe that Near-Death Experiences are evidence for an afterlife.

This got the attention of these Chapman students and they got right into it. We had them write an Opinion Editorial as if it were going to be submitted to the New York Times or Wall Street Journal, in order to teach them how to communicate clearly and succinctly to a wider audience about a controversial idea (they could pick any idea from the course, which was quite broad in scope). They also had to do an 18-minute TED talk or participate in a 2 x 2 debate. It won’t surprise you to know that most 18-year old students are well aware of TED talks and have watched numerous videos at TED.com, including my own. The point was to teach them how to organize a short talk and say something meaningful in a brief period of time. The point of this exercise was to have a point! They did. And then some. Most were skeptical of the paranormal and the supernatural, so of course we had a few pro-atheist TED talks, but there were a couple of pro-God and pro-paranormal talks as well, just to spice things up. The most memorable talk had to be by a student who in explaining evolutionary psychology and why natural selection shaped us to prefer (that is, find attractive) symmetrical faces, clear complexions, shapely bodies (wide shoulders and a narrow waist in men, an hourglass figure in women with a 0.7 waist-to-hip ratio), and the like, then put up a slide of Rosie O’Donnell as an illustration of pure ugliness and why no male could possibly find her attractive. Needless to say, in the requisite Q&A (every talk had one) the women in the class made mince meat of this fellow.

As well, the students were given a midterm and final exam in essay format based on the readings for the course, which included my own Why People Believe Weird Things and The Believing Brain, bookended around Carl Sagan’s The Demon-Haunted World, Stuart Vyse’s Believing in Magic, and the book they all loved the most: Richard Wiseman’s Paranormality. In Paranormality, Wiseman provides numerous examples of how to test paranormal claims, and this led to the students final major assignment, which was a research project and YouTube video production to accompany it (or a Powerpoint presentation of their data). Check out the student projects that we have already posted in our Skeptical Studies Curriculum Resource Center.

The point of these exercises was to get students doing things that involve skepticism, not just reading and answering test questions, as well as encourage them to have fun doing so by trying to make their presentations entertaining as well as educational.

I also tried something new (for me anyway) in grading: Anondah and I independently rated each student’s OpEd, TED talk, midterm and final answer, research project, and YouTube video or Powerpoint presentation, then compared our ratings, added them up and divided by 2. During the student talks and presentations Anondah and I sat at the back of the room as the “judges”—I joked that we were like Simon and Paula on American Idol playing good cop-bad cop. That was kinda fun.

Because the course deals with many serious subjects, such as religious beliefs, political positions, social attitudes, and the like, we also outlined for them our policy on controversies:

Controversy Disclaimer

This course deals with many controversial topics related to people’s deepest held beliefs about god and religion, science and technology, politics and economics, morality and ethics, and social attitudes and cultural assumptions. I hope to challenge you to think about your beliefs in all these areas, and others. My goal is to teach you how to think about your beliefs, not what to think about them. I have my own set of beliefs that I have developed over the decades, which I do not attempt to hide or suppress; indeed, as a public intellectual I am regularly called upon to present and defend my beliefs in lectures, debates, interviews, articles, reviews, and opinion editorials. But in the classroom my goal is not to convince you of anything other than to think about your beliefs. I am often asked “why should we believe you?” My answer: “You shouldn’t.” Be skeptical, even of skeptics.

Finally, I explained that the goal of the course was parallel to the goal of the overall skeptical movement (as I see it anyway):

The Goals of the Skeptical Movement

Debunking. There’s a lot of bunk and someone needs to debunk it. Like the bunko squads of police departments busting scammers and con artists, skeptics bust myths.

Understanding. It’s not enough to debunk the things that people believe. We also want to understand why they believe. Through understanding comes enlightenment.

Enlightenment. The power of positive skepticism linked to reason, rationality, logic, empiricism, and science offers us a world wondrous and awe-inspiring enough.

If you want to teach your own course in Skepticism 101, or are already teaching such a course, I encourage you to go to our webpage and have a look and take what you need. All materials are free.

If you would like to support the Skepticism 101 project, please make a tax-deductible donation. We are happy to accept anything you can afford, but might I suggest a $100 donation or even an automatically recurring monthly donation of $5 or $10?

In appreciation to all those who have already help support the Skepticism 101 project.

July 1, 2012

Aunt Millie’s Mind

are neurochemistry

“WHERE IS THE EXPERIENCE OF RED IN YOUR BRAIN?” The question was put to me by Deepak Chopra at his Sages and Scientists Symposium in Carlsbad, Calif., on March 3. A posse of presenters argued that the lack of a complete theory by neuroscientists regarding how neural activity translates into conscious experiences (such as “redness”) means that a physicalist approach is inadequate or wrong. “The idea that subjective experience is a result of electrochemical activity remains a hypothesis,” Chop ra elaborated in an e-mail. “It is as much of a speculation as the idea that consciousness is fundamental and that it causes brain activity and creates the properties and objects of the material world.” “Where is Aunt Millie’s mind when her brain dies of Alzheimer’s?” I countered to Chopra. “Aunt Millie was an impermanent pattern of behavior of the universe and returned to the potential she emerged from,” Chopra rejoined. “In the philosophic framework of Eastern traditions, ego identity is an illusion and the goal of enlightenment is to transcend to a more universal non local, nonmaterial identity.”

The hypothesis that the brain creates consciousness, however, has vastly more evidence for it than the hypothesis that consciousness creates the brain. Damage to the fusiform gyrus of the temporal lobe, for example, causes face blindness, and stimulation of this same area causes people to see faces spontaneously. Stroke-caused damage to the visual cortex region called V1 leads to loss of conscious visual perception. Changes in conscious experience can be directly measured by functional MRI, electroencephalography and single-neuron recordings. Neuroscientists can predict human choices from brain-scanning activity before the subject is even consciously aware of the decisions made. Using brain scans alone, neuroscientists have even been able to reconstruct, on a computer screen, what someone is seeing.

Thousands of experiments confirm the hypothesis that neurochemical processes produce subjective experiences. The fact that neuroscientists are not in agreement over which physicalist theory best accounts for mind does not mean that the hypothesis that consciousness creates matter holds equal standing. In defense, Chopra sent me a 2008 paper published in Mind and Matter by University of California, Irvine, cognitive scientist Donald D. Hoffman: “Conscious Realism and the Mind-Body Problem.” Conscious realism “asserts that the objective world, i.e., the world whose existence does not depend on the perceptions of a particular observer, consists entirely of conscious agents.” Consciousness is fundamental to the cosmos and gives rise to particles and fields. “It is not a latecomer in the evolutionary history of the universe, arising from complex interactions of unconscious matter and fields,” Hoffman writes. “Consciousness is first; matter and fields depend on it for their very existence.”

Where is the evidence for consciousness being fundamental to the cosmos? Here Hoffman turns to how human observers “construct the visual shapes, colors, textures and motions of objects.” Our senses do not construct an approximation of physical reality in our brain, he argues, but instead operate more like a graphical user interface system that bears little to no resemblance to what actually goes on inside the computer. In Hoffman’s view, our senses operate to construct reality, not to reconstruct it. Further, it “does not require the hypothesis of independently existing physical objects.”

How does consciousness cause matter to materialize? We are not told. Where (and how) did consciousness exist before there was matter? We are left wondering. As far as I can tell, all the evidence points in the direction of brains causing mind, but no evidence indicates reverse causality. This whole line of reasoning, in fact, seems to be based on something akin to a “God of the gaps” argument, where physicalist gaps are filled with nonphysicalist agents, be they omniscient deities or conscious agents.

No one denies that consciousness is a hard problem. But before we reify consciousness to the level of an independent agency capable of creating its own reality, let’s give the hypotheses we do have for how brains create mind more time. Because we know for a fact that measurable consciousness dies when the brain dies, until proved otherwise, the default hypothesis must be that brains cause consciousness. I am, therefore I think.

June 19, 2012

The Reality Distortion Field

is a double-edge sword

Robert Friedland was a long-haired, sandal-wearing, spiritual-seeking proprietor of an apple farm commune and student at Reed College when he met Steve Jobs in 1972 and taught the future Apple computer founder a principle called the “reality distortion field” (RDF). Macintosh software designer Bud Tribble recalled, “In his presence, reality is malleable. He can convince anyone of practically anything.” And yet the blade could cut two ways: “It was dangerous to get caught in Steve’s distortion field, but it was what led him to actually be able to change reality.” Another Mac software designer named Andy Hertzfeld said, “The reality distortion field was a confounding mélange of a charismatic rhetorical style, indomitable will, and eagerness to bend any fact to fit the purpose at hand.” The first Mac team manager Debi Coleman said Jobs “reminded me of Rasputin. He laser-beamed in on you and didn’t blink. It didn’t matter if he was serving purple Kool-Aid. You drank it.” And yet when the power was properly channeled, “You did the impossible, because you didn’t realize it was impossible.”

The RDF is an extreme version of what the psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls a “pervasive optimistic bias” in his 2011 book Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). “Most of us view the world as more benign than it really is, our own attributes as more favorable than they truly are, and the goals we adopt as more achievable than they are likely to be.” For example, only 35 percent of small businesses survive in the U.S., but when surveyed 81 percent of entrepreneurs assessed their odds of success at 70 percent, and 33 percent went so far as to put it at 100 percent! “One of the benefits of an optimistic temperament is that it encourages persistence in the face of obstacles,” Kahneman notes, while also citing study in which 47 percent of inventors “continued development efforts even after being told that their project was hopeless, and on average these persistent (or obstinate) individuals doubled their initial losses before giving up.” Failure may not be an option in the minds of entrepreneurs, but it is all too frequent in reality, which is why another bias called “loss aversion” is felt by most. Thus, Jobs’s success story is also an example of a selection bias whereby those who failed tend not to have biographies.

Jobs’s optimistic bias was off the charts. According to his biographer Walter Isaacson, “At the root of the reality distortion was Jobs’s belief that the rules didn’t apply to him. He had the sense that he was special, a chosen one, an enlightened one.” Jobs’s self-importance and will to power over rules that applied only to others were reflected in numerous ways: legal (parking in handicapped spaces, driving without a license plate), moral (accusing Microsoft of ripping off Apple when both took from Xerox the idea of the mouse and the graphical user interface), personal (refusing to acknowledge paternity of his daughter Lisa even after an irrefutable paternity test), and practical (besting resource-heavy giants IBM and Xerox in the computer market with a fraction of their budgets). Jobs’s RDF unquestionably contributed to his success in revolutionizing no fewer than six industries: personal computers, animated films, digital music, cell phones, tablet computing, and digital publishing.

There was, however, one reality his distortion field could not bend to his will: cancer. In 2003 Jobs was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, which further tests revealed to be an islet cell or pancreatic neuroendrocrine tumor that is treatable with surgical removal, which Jobs refused. “I really didn’t want them to open up my body, so I tried to see if a few other things would work,” he later admitted to Isaacson with regret. Those other things included consuming large quantities of carrot and fruit juices, fasting, bowel cleansings, hydrotherapy, acupuncture and herbal remedies, a vegan diet, and, says Isaacson, “a few other treatments he found on the Internet or by consulting people around the country, including a psychic.” They didn’t work, and in the process we find the alternative medicine question, “What’s the harm?,” answered in the form of an irreplaceable loss to humanity.

Out of this heroic tragedy a lesson emerges: reality must take precedence over willful optimism, for nature cannot be distorted.

June 5, 2012

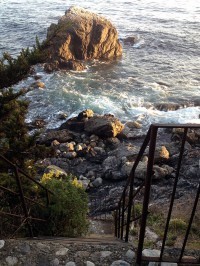

A Weekend of Woo (Or why I love the Esalen Institute)

For the forth time in my life I journeyed north on Pacific Coast Highway along the ragged California coast line north of San Simeon and the Hearst Castle where the road turns twisty and the cliffs bend vertical. The Esalen Institute is nestled on the ocean side of the highway atop some bluffs dotted with buildings that include yoga rooms, Yurts, Spartan housing overlooking the ocean, a soup kitchen-like cafeteria serving spectacularly healthy food (lots of Tofu and veggies, no tri-tips or ribs), and workshops catering to just about every belief ever investigated and found wanting in the pages of Skeptic magazine.

Nevertheless, I loved my time there once again, not only for the breathtaking scenery and unprecedented views, or the invigorating cycling and hiking, or the natural hot springs pouring out of the mountain and into elegantly designed hot tubs (clothing optional, and most opt to go without), but for the apparent incongruity made congruous when we consider our mission as skeptics to take our message of science and critical thinking to those who need to hear it most.

My workshop was entitled “Science, Spirituality, and the Search for Morality and Meaning.” First, I must say that the 24 participants in my workshop were already as skeptical as one might find at one of our Sunday Caltech lecture series meetings and dinners. All were well-read in the sciences and humanities to the point that I learned as much as I taught, and the ensuing conversations both during and after the lectures, along with at the meals, were exceptional.

Thus, I needed to trek down to the hot tubs in order to really sample the population of attendees at other workshops that weekend. What I heard was most entertaining, as well as educational in terms of why people believe weird things. To be fair, the workshop on couples massage sounded thoroughly grounded in the reality of how relaxing it can be to give and receive a massage, and I have no doubt that the couples in this class were probably brought closer to one another and learned a skill they could definitely take home with them.

But there were other workshops that sounded more like the touchy feely without the touchy. This goes by the generic descriptor of “energy work.” Lots of hot tub soakers waxed enthusiastic about getting their chakras adjusted, their Chi energy re-energized, the miracles of acupuncture, acupressure, and Chiropractic, and how this and that “natural healer” could cure everything from migraines and depression to pain and bowel ailments.

(A note parenthetical on the clothing-optional hot tubs: if you’ve never opted as such it probably sounds either positively off-putting or on-turning, depending on your imagination. It is neither. It is nothing, in fact. No one cares or stares. It actually does seem natural and normal in that environment. At night it’s pretty dark so you can’t really see anything anyway, and during the day people are discrete and polite. It’s all cool.)

If there is one work that best captures how people think (or miss-think) at Esalen it is “anecdotal.” Everything is couched in anecdotes. “I tried this” — “This worked for me” — “I know someone who said he used X for his headache” — “Ever since I started doing X my headaches have disappeared” and so on. No one ever discusses studies, experiments, control v. experimental groups, epidemiological studies, and the like. I heard one guy in the hot tub proclaim “I’m a skeptic, a man of science,” which was followed by a litany of anecdotes about the amazing wonders of this acupuncturist he’s been going to. Revealingly, someone asked him if the needles hurt. He pronounced without hesitation that the needles never ever hurt. And yet five minutes later he confessed that the ones in his hand, wrist, forearm, and shins all hurt like hell.

The problem with anecdotes is that 10 anecdotes are no better than 1, and 100 anecdotes are no better than 10. As I’ve repeated numerous times in numerous books and articles, “anecdotes do not make a science.” Or as a new trope going around these days (the source of which escapes me), “the plural of anecdote is not data.” (Who first said that? Anyone? Anyone? Bueller?) Anecdotes are fun and interesting, and they may even lead one to construct an experiment to test a hypothesis (“does sitting naked in a natural hot spring tub lead to anecdotal thinking?”), but by themselves they are often worse than nothing because they lead one to draw conclusions that are more often than not misleading or wrong.

Thus it is that in one of my hot tub sessions I brought up the famous 1990’s “Emily experiment,” in which little Emily Rosa, for her 4th grade science project, tested Therapeutic Touch (TT, or the original touchy feeling without the touchy) by observing under controlled conditions if this “healers” could even detect her “energy field” behind an opaque screen in which they slid their hands through two cut out openings at the bottom. Emily flipped a coin to determine whether she would hold her hand a few inches above the TT therapist’s left or right hand, at which point they had to declare which hand detected the energy field. As a simple coin-flip model it’s a 50/50 guess. Emily’s subjects scored less than 50%, worse than chance, even though before the experiment began they all declared that they could with 100% certainty detect her energy field standing before her. After I recounted this experiment the other people in the tub said something to the effect of “um,” and “oh, uh, okay,” and “well…uh…um.” I have no idea, of course, if they went back to their rooms and revisited their deepest held beliefs about human “energy,” but I hope to have planted a small seed that may one day grow into a skeptical tree. Who knows?

Since so much of the Esalen Institute is experiential, I’ll let my iPhone pics speak louder than my words for what it was like experiencing Esalen, one of my favorite places on the planet. (Click any image to enlarge it and view the entire image gallery.)

June 1, 2012

The Science of Righteousness

are so tribal and politics so divisive

Which of these two narratives most closely matches your political perspective?

Once upon a time people lived in societies that were unequal and oppressive, where the rich got richer and the poor got exploited. Chattel slavery, child labor, economic inequality, racism, sexism and discriminations of all types abounded until the liberal tradition of fairness, justice, care and equality brought about a free and fair society. And now conservatives want to turn back the clock in the name of greed and God.

Once upon a time people lived in societies that embraced values and tradition, where people took personal responsibility, worked hard, enjoyed the fruits of their labor and through charity helped those in need. Marriage, family, faith, honor, loyalty, sanctity, and respect for authority and the rule of law brought about a free and fair society. But then liberals came along and destroyed everything in the name of “progress” and utopian social engineering.

Although we may quibble over the details, political science research shows that the great majority of people fall on a left-right spectrum with these two grand narratives as bookends. And the story we tell about ourselves reflects the ancient tradition of “once upon a time things were bad, and now they’re good thanks to our party” or “once upon a time things were good, but now they’re bad thanks to the other party.” So consistent are we in our beliefs that if you hew to the first narrative, I predict you read the New York Times, listen to progressive talk radio, watch CNN, are pro-choice and anti-gun, adhere to separation of church and state, are in favor of universal health care, and vote for measures to redistribute wealth and tax the rich. If you lean toward the second narrative, I predict you read the Wall Street Journal, listen to conservative talk radio, watch Fox News, are pro-life and anti–gun control, believe America is a Christian nation that should not ban religious expressions in the public sphere, are against universal health care, and vote against measures to redistribute wealth and tax the rich.

Why are we so predictable and tribal in our politics? In his remarkably enlightening book, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (Pantheon, 2012), University of Virginia psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues that to both liberals and conservatives, members of the other party are not just wrong; they are righteously wrong—morally suspect and even dangerous. “Our righteous minds made it possible for human beings,” Haidt argues, “to produce large cooperative groups, tribes, and nations without the glue of kinship. But at the same time, our righteous minds guarantee that our cooperative groups will always be cursed by moralistic strife.” Thus, he shows, morality binds us together into cohesive groups but blinds us to the ideas and motives of those in other groups.

The evolutionary Rubicon that our species crossed hundreds of thousands of years ago that led to the moral hive mind was a result of “shared intentionality,” which is “the ability to share mental representations of tasks that two or more of [our ancestors] were pursuing together. For example, while foraging, one person pulls down a branch while the other plucks the fruit, and they both share the meal.” Chimps tend not to display this behavior, Haidt says, but “when early humans began to share intentions, their ability to hunt, gather, raise children, and raid their neighbors increased exponentially. Everyone on the team now had a mental representation of the task, knew that his or her partners shared the same representation, knew when a partner had acted in a way that impeded success or that hogged the spoils, and reacted negatively to such violations.” Examples of modern political violations include Democrat John Kerry being accused of being a “flip-flopper” for changing his mind and Republican Mitt Romney declaring himself “severely conservative” when it was suggested he was wishy-washy in his party affiliation.

Our dual moral nature leads Haidt to conclude that we need both liberals and conservatives in competition to reach a livable middle ground. As philosopher John Stuart Mill noted a century and a half ago: “A party of order or stability, and a party of progress or reform, are both necessary elements of a healthy state of political life.”

May 22, 2012

The Unknown Unknowns

This review of Ignorance: How it Drives Science by Stuart Firestein (Oxford University Press, May 2012, ISBN 13: 97801-998-28074) was originally published in Nature, 484, 446–447 (26 April 2012) as “Philosophy: What we don’t know.”

At a press conference on February 12, 2002, the United State Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld employed epistemology to the explain U.S. foreign entanglements and their unintended consequences: “There are known knowns. There are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns. That is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns, the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

It is this latter category especially that is the focus of Stuart Firestein’s sparkling and innovative look at ignorance, and how it propels the scientific process forward. Firestein is Professor and Chair of the Department of Biological Sciences at Columbia University, where he teaches a wildly popular course on ignorance, inviting scientists in as guest speakers to tell students not what they know but what they don’t know, and even what they don’t know that they don’t know. (Would you rather earn an A or an F in a class called “Ignorance”?, he muses.) This is a slim volume about a fat topic, but Firestein captures the essence of the problem by contrasting the public’s understanding of science as a step-wise systematic algorithm of grinding through experiments that churn out data sets to be analyzed statistically and published in peer-reviewed journals after a process of observation, hypothesis, manipulation, further observation, and new hypothesis testing, with the Princeton University mathematician Andrew Wiles’ description of science as “groping and probing and poking, and some bumbling and bungling, and then a switch is discovered, often by accident, and the light is lit, and everyone says, ‘Oh, wow, so that’s how it looks,’ and then it’s off into the next dark room, looking for the next mysterious black feline” (p. 2), in reference to the old proverb: “It is very difficult to find a black cat in a dark room. Especially when there is no cat.”

If ever there was a time to think seriously about ignorance it is in our age of digital knowledge. Consider an Exabyte of data, or one billion gigabytes (typical thumb drives that most of us carry around consist of a couple of gigabytes storage capacity). It has been estimated that from the beginning of civilization around 5,000 years ago to the year 2003, all of humanity created a grand total of five exabytes of digital information. From 2003 through 2010 we created five exabytes of digital information every two days. By 2013 we will be producing five exabytes every ten minutes. The 2010 total of 912 exabytes is the equivalent of 18 times the amount of information contained in all the books ever written. It isn’t knowledge that we need more of; it is how to think about what we know and what we don’t know that is becoming ever more critical in science, through a process Feinstein calls “controlled neglect.” Scientists “don’t stop at the facts,” he explains, “they begin there, right beyond the facts, where the facts run out” (p. 12). It must be this way, he argues, because “the vast archives of knowledge seem impregnable, a mountain of facts that I could never hope to learn, let alone remember” (p. 14). Doctors and lawyers and engineers need many facts at their ready, as do scientists, but for the latter “the facts serve mainly to access the ignorance” because this is where the action is. “Want to be on the cutting edge? Well, it’s all, or mostly, ignorance out there. Forget the answers, work on the questions” (pp. 15–16).

To Rumsfeld’s epistemological categories Firestein would one add more: unknowable unknowns, “things that we cannot know due to some inherent and implacable limitation.” He puts history in this category, but I would not, for if we take the broader construct of history as anything that happened before the present then most of astronomy, cosmology, geology, archaeology, paleontology, and evolutionary biology are historical sciences, subject to testing hypotheses no less rigorously than their experimental scientists in the lab. And I worry slightly that an overemphasis on our ignorance about this or that claim opens the door to creationists, Holocaust deniers, climate deniers, and post-modern deconstructions who wish to challenge mainstream scientists because of religious or political agendas. Acknowledging our ignorance is good, but let’s acknowledge and celebrate what science has confidently given us in the way of well-supported theories.

The Believing Brain

by Michael Shermer

In this book, I present my theory on how beliefs are born, formed, nourished, reinforced, challenged, changed, and extinguished. Sam Harris calls The Believing Brain “a wonderfully lucid, accessible, and wide-ranging account of the boundary between justified and unjustified belief.” Leonard Mlodinow calls it “a tour de force integrating neuroscience and the social sciences.”

Order the autographed hardcover

Order the unabridged audio CD

Order the Kindle edition

Order the iBook edition

Listen to the Prologue for free

That caveat aside, Ignorance includes an important discussion about scientific errors and their propagation in textbooks. I’m embarrassed to admit that I perpetrated one of these myself in my latest book, The Believing Brain, in which I repeated as gospel the “fact” that the human brain contains about 100 billion neurons. Firestein reports that his neuroscience colleague Suzana Herculano-Houzel told him it is actually around 80 billion (after undertaking an actual neural count!), and that there are an order of magnitude fewer glial cells than the textbooks report. As well, Firestein continues, the “neural spike” every neuroscientist measures and every student learns as the fundamental unit of neural activity when the cell fires, is itself a product of the electrical apparatus employed in the lab and ignores other forms of neural activity. And if that isn’t bad enough, even the famous “tongue map” in which sweet is sensed on the tip, bitter on the back, and salt and sour on the sides that is published in countless popular and medical textbooks is wrong and the result of a mistranslation of a German physiology textbook by Professor D. P. Hanig, and that the localization differences are much more complex and subtle.

These and other errors are the result of our lack of skepticism of the knowledge we have and our lack of respect for ignorance. “Ignorance works as the engine of science because it is virtually unbounded, and that makes science much more expansive” (p. 54). Indeed it is, and as the expanding sphere of scientific knowledge comes into contact with an ever increasing surface area of the unknown (thus, the more you know the more you know how much you don’t know), we would do well to remember the mathematical principle of surface area to volume ratio: as a sphere increases the ratio of its volume to surface area increases. Thus, in this metaphor, as the sphere of scientific knowledge increases, the ratio of the volume of the known to the surface area of the unknown increases, and it is here where we can legitimately make a claim of true and objective progress.

May 14, 2012

Are Religious People Healthier?

Michael Shermer on MSNBC’s Dylan Ratigan Show on religion, health, happiness, longevity, & self control…

Visit msnbc.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

May 8, 2012

Atheist Nation

Where in the world are the atheists? That is, in what part of the globe will one find the most people who do not believe in God? Answer: East Germany at 52.1%. The least? The Philippines at less than 1%. Predictably, strong belief shows a reverse pattern: 84% in the Philippines to 4% in Japan, with East Germany at the second lowest in strong belief at 8%. Not surprising, those who believe in a personal God “who concerns himself with every human being personally” is lowest in East Germany at 8% and highest in the Philippines at 92%.

These numbers, and others, were collected and crunched by Tom W. Smith of the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago, in a paper entitled “Beliefs About God Across Time and Countries,” produced for the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) and released on April 18, 2012. Smith writes: “Countries with high atheism (and low strong belief) tend to be ex-Socialist states and countries in northwest Europe. Countries with low atheism and high strong belief tend to be Catholic societies, especially in the developing world, plus the United States, Israel, and Orthodox Cyprus.”

Many religious scholars invoke the “secularization thesis” to explain lower religiosity in Northern European countries (compared to the United States) in which mass education, especially in the sciences, coupled to the fact that governments do what religions traditionally did in the past in taking care of the poor and needy. With a tight social safety net religions simply fall into disuse; with a porous social safety net people fall through the cracks and are picked up by religions. Other scholars have suggested a “supply side” explanation for the difference between the U.S. and Europe, in which churches and religions in America must compete for limited resources and customers and thus have ratcheted up the quality of religious products and services: mega churches with rock music, baby sitting, BBQs, and even free parking! Smith seems to find evidence of both forces at work, noting that “In the case of Poland, it appears that its strong Catholicism trumps the secularizing influence of Socialism,” whereas elsewhere in the world “there is also evidence that religious competition and/or religious conflict may stimulate higher belief.”

Religion is a complex phenomenon and thus explanations are likely to be complex. (I find that in the social sciences Occam’s razor is rarely true—the simpler explanation is not only usually wrong, it can be terribly misleading.) Smith notes, for example, that “Belief is high in Israel which of course has a sharp conflict between Judaism and Islam, in Cyprus which is divided along religious and ethnic lines into Greek/Orthodox and Turkish/Muslim entities, and in Northern Ireland which is split between Protestant and Catholic communities and shows much higher belief levels than the rest of the United Kingdom.” In the United States there is relatively little overt religious conflict, but intense religious competition across both major religions and denominations within Christianity.”

The outlier appears to be Japan: “The one country that shows a low association between the level of atheism and strong belief is Japan. Japan ranked lowest on strong belief, but also in the lower half on atheism (a difference of 18 positions across the two rankings when the average difference in positions was only 2.7 places). Japan is distinctive among countries in having the largest number of people (32%) in the middle categories of believing sometimes and the agnostic, not knowing response. This pattern is consistent with a general Japanese response pattern of avoiding strong, extreme response options.”

Changes in God beliefs were modest from 1991 through 2008, with the percent saying they were atheists increasing in 15 of 18 countries at an average rise of 1.7%. Between 1998 and 2008 the atheist gain was bigger, with an average increase of 2.3 points in 23 of 30 countries. Predictably, again, the corresponding belief in God decreased by roughly the same amount that atheism grew. The exceptions were Israel, Russia and Slovenia where from 1991 to 2008 there was a consistent movement towards greater belief and less atheists. Israel’s religious shift was a result of an increase in orthodox Jewish and right-wing population, “and the relative decline of the more secular and leftist segment in Israeli society.”

Most interestingly, Smith computed the overall gains and loses of religious beliefs comparing those who say “I believe in God now, but I didn’t used to.” With those say “I don’t believe in God now, but I used to.” “In 2008 there was a net gain in belief across the life course in 12 countries and a decline in 17 countries. The gains averaged 4.1 points and the losses -7.0 points for an overall change of -2.4 points.” The shifts also varied by age, with older people gaining in belief while younger people decreasing in belief. Smith concludes his study with this projection for the future of atheism:

“If the modest, general trend away from belief in God continues uninterrupted, it will accumulate to larger proportions and the atheism that is now prominent mainly in northwest Europe and some ex-Socialist states may spread more widely.”

In case you’re wondering, the percentage of Americans who say “I don’t believe in God” was 3% at 4th lowest in the world, and who said “I know God really exists and I have no doubt about it” at 60.6%, the 5th highest in the world. Americans who agreed “I don’t believe in God and I never have” was 4.4 at 6th lowest in the world, who agreed “I believe in God now and I always have at 80.8% at 3rd highest in the world. In terms of the changes in atheism and belief in God over time, from 1991 to 2008 the U.S. showed an increase of 0.7% atheists and -0.2 from 1998–2008; in 2008, taking those who said “I believe in God now, but I didn’t used to” minus “I don’t believe in God now, but I used to” nets +1.4 in the United States.

The paper is chockablock full of data figures. Here’s the press release for more information.

May 1, 2012

Much Ado about Nothing

instead of nothing

WHY IS THERE SOMETHING RATHER THAN NOTHING? This is one of those profound questions that is easy to ask but difficult to answer. For millennia humans simply said, “God did it”: a creator existed before the universe and brought it into existence out of nothing. But this just begs the question of what created God—and if God does not need a creator, logic dictates that neither does the universe. Science deals with natural (not supernatural) causes and, as such, has several ways of exploring where the “something” came from.

Multiple universes. There are many multiverse hypotheses predicted from mathematics and physics that show how our universe may have been born from another universe. For example, our universe may be just one of many bubble universes with varying laws of nature. Those universes with laws similar to ours will produce stars, some of which collapse into black holes and singularities that give birth to new universes—in a manner similar to the singularity that physicists believe gave rise to the big bang.

M-theory. In his and Leonard Mlodinow’s 2010 book, The Grand Design, Stephen Hawking embraces “M-theory” (an extension of string theory that includes 11 dimensions) as “the only candidate for a complete theory of the universe. If it is finite—and this has yet to be proved—it will be a model of a universe that creates itself.”

Quantum foam creation. The “nothing” of the vacuum of space actually consists of subatomic spacetime turbulence at extremely small distances measurable at the Planck scale—the length at which the structure of spacetime is dominated by quantum gravity. At this scale, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle allows energy to briefly decay into particles and antiparticles, thereby producing “something” from “nothing.”

Nothing is unstable. In his new book, A Universe from Nothing, cosmologist Lawrence M. Krauss attempts to link quantum physics to Einstein’s general theory of relativity to explain the origin of a universe from nothing: “In quantum gravity, universes can, and indeed always will, spontaneously appear from nothing. Such universes need not be empty, but can have matter and radiation in them, as long as the total energy, including the negative energy associated with gravity [balancing the positive energy of matter], is zero.” Furthermore, “for the closed universes that might be created through such mechanisms to last for longer than infinitesimal times, something like inflation is necessary.” Observations show that the universe is in fact flat (there is just enough matter to slow its expansion but not to halt it), has zero total energy and underwent rapid inflation, or expansion, soon after the big bang, as described by inflationary cosmology. Krauss concludes: “Quantum gravity not only appears to allow universes to be created from nothing—meaning…absence of space and time—it may require them. ‘Nothing’—in this case no space, no time, no anything!—is unstable.”

The other hypotheses are also testable. The idea that new universes can emerge from collapsing black holes may be illuminated through additional knowledge about the properties of black holes, which are being studied now. Other bubble universes might be detected in the subtle temperature variations of the cosmic microwave background radiation left over from the big bang of our own universe. NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) spacecraft is collecting data on this radiation. Additionally, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) is designed to detect exceptionally faint gravitational waves. If there are other universes, perhaps ripples in gravitational waves will signal their presence. Maybe gravity is such a relatively weak force (compared with electromagnetism and the nuclear forces) because some of it “leaks” out to other universes.

Even if God is hypothesized as the creator of the laws of nature that caused the universe (or multiverse) to pop into existence out of nothing—if such laws are deterministic—then God had no choice in the creation of the universe and thus was not needed. In any case, why turn to the supernatural when our understanding of the natural is still in its incipient stages? We would be wise to heed this skeptical principle: before you say something is out of this world, first make sure that it is not in this world.

April 24, 2012

Shermer in Seminary School

On Friday, April 13, 2012 in the chapel of the New Orleans Baptist Seminary I debated the Liberty University philosopher and theologian Gary Habermas on the question: “Is There Life After Death?” I went first. I stated that since Gary is taking the affirmative I’m suppose to defend the negative, but in fact when it comes to the afterlife, “I’m for it!” Tellingly, that line didn’t get the usual laugh it engenders in audiences, but then in seminary school the afterlife is a deadly serious subject. I began with this thought experiment:

Imagine yourself dead. What picture comes to mind? Your funeral with a casket surrounded by family and friends? Complete darkness and void? In either case you are still conscious and observing the scene.

I then outlined the problem we all have in thinking about life after death: we cannot envision what it is like to be dead any more than we can visualize ourselves before we were born, and yet everyone who ever lived has died so death is inevitable. This leads to either depression or humor. I prefer the latter. For example, Steven Wright: “I intend to live forever—so far, so good.” Or Woody Allen: “It’s not that I’m afraid to die. I just don’t want to be there when it happens.”

Of course, you won’t be there when it happens because to experience anything you must be conscious, and you are not conscious when you are dead. I then outlined four theories of life after death, gleaned from my recent Scientific American column based on Stephen Cave’s marvelous new book, Immortality, which I highly recommend reading.

The Four Theories of Immortality

1. Staying Alive. That is, one way to achieve immortality is to not die. I then reviewed the various realities involved, such as the 100 billion people who lived before us who have died, and the various problems involved with longevity efforts, genetic engineering to change the telomeres involved in aging, cryonics, and Tulane University physicist Frank Tipler’s Omega Point theory about how we will all be resurrected in the far future of the universe in super computer-generated virtual realities.

2. Resurrection. I then explained Theseus’s Ship and Shermer’s Mustang: how Poseidon’s son Theseus sailed to Crete to slay monster Minotaur and how his ship was preserved for posterity but rotted over time and every board was replaced with new wood—is that still Theseus’s ship? Ditto my 1966 Mustang, which I purchased in 1971 and wrecked and ruined to the point where there was hardly an original part on it when I still sold it as a classic car 16 years later. Is that really still a 1966 Mustang? I then segued into discussing the transformation problem (how could you be reassembled just as you were and yet this time be invulnerable to disease and death?) and Julia Sweeney’s challenge to the Mormon boys who told her that she would be made whole again and when she asked them if she’d have her uterus back (which she had removed because of cancer) told them “I don’t want it back!” And what age are you resurrected? 5, 29, 85? And how would a duplicate you be any different from your twin who happens to have your same memories?

3. Soul. I explained to these young seminarians that there isn’t a shred of evidence for anything like a “soul” that survives death, no new physical system that scientists have discovered to allow soul stuff to survive. I noted that Thomas Jefferson made this killer observation: we do not understand how the mind causes the brain to act, or how thoughts are transduced into physical movements. Adding a soul only doubles the mystery, as believers would then have to explain how the soul effects the mind, and how the mind effects the brain. In reality, I explains, there is no soul or mind. Just brain. I asked rhetorically: Under anaesthesia, where’s your soul? Why is it knocked out? And: If the soul can see, why can’t the souls of blind people see when they are alive?

4. Legacy: glory, reputation, historical impact, or children. But as Woody Allen said: “I don’t want to live on in the hearts and minds of my countrymen. I want to live on in my apartment.” Clearly this is not what most people desire for life after death, so…

Which Afterlife Theory is Correct?

Which religion’s afterlife story is the right one? Egyptian, Christian, Mormon, Scientology, Buddhist, Hindu, Deepak’s Quantum Consciousness? What are the odds that Gary Habermas’s theory of the afterlife will happen to match that of the God and Religion he believes in? Virtually 100%!

Afterlife myths follow the same pattern as all religious myths: where you happened to have been born and at what time in history determines which myth you believe. To an anthropologist from Mars these are all indistinguishable.

Where do you go to live after death?

I then noted that ever since Copernicus and the rise of modern astronomy and cosmology there is no place for heaven. This has led some to speculate that perhaps it is in another dimension. But those dimensions are physical systems subject to the laws of entropy, so that doesn’t help. I then recounted a few other “theories” of the afterlife:

Egyptians: a physical place far above the Earth in a “dark area” of space where there were no stars, basically beyond the Universe.

Vikings: Valhalla—a big hall in which to drink beer and get ready to fight again

Muslims: “the Garden” with rivers, fountains, shady valleys, trees, milk, honey and wine—all the things Arabian desert people crave, plus 72 virgins for the men. (No one seems to have asked what the women want.)

Christians: eternity with angels at the throne of God.

Hitchens: The Christian heaven is a Celestial North Korea at the throne of the dear leader

Who’s to say that Heaven will be good? What if it isn’t? What proof do we have?

What if it’s boring? My college philosophy professor Richard Hardison once asked rhetorically: “Do they have tennis courts and golf courses there?”

Ethnologist Elie Reclus describes Christian missionaries attempting to convert Inuits with the promise of a God-centered heaven. Inuit: “And the seals? You say nothing about the seals. Have you no seals in your heaven?” “Seals? Certainly not. We have angels and archangels…the 12 apostles and 24 elders, we have…” “That’s enough. Your heaven has no seals, and a heaven without seals is not for us!”

Evidence for Life After Death

Talking to the dead: Frank’s Box/Telephone to the Dead/Psychics.

Information Fields and the Universal Life Force. —21 Grams: 1907 Duncan MacDougall tried to find out by weighing six dying patients before and after their death—medical journal American Medicine: a 21-gram difference —Rupert Sheldrake

ESP and Evidence of Mind. Experimental research on psi and telepathy

Near-Death Experiences

Clue: “Near” death. Not dead.

80% of people who almost die and recover have no NDEs at all.

OBE: people “see” themselves from above. But what is doing the seeing?

TPJ (temporo-parietal junction) stimulation = OBE

G-Force Induced Loss of Consciousness, Dr. James Whinnery: “dreamlets,” or brief episodes of tunnel vision, sometimes with a bright light at the end of the tunnel, as well as a sense of floating, sometimes paralysis, and often euphoria and a feeling of peace and serenity when they came back to consciousness. Over 1,000, apoxia, oxygen deprivation: “vivid dreamlets of beautiful places that frequently include family members and close friends, pleasurable sensations, euphoria, and some pleasurable memories.”

Neurochemicals such as endorphins, serotonin, and dopamine produce feelings of serenity and peace.

Methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) triggers long-forgotten memories and produces the feeling of age regression, while di-methyl-tryptamine (DMT)—AKA “the spirit molecule”—causes the dissociation of the mind from the body and is the hallucinogenic substance in ayahuasca, a drug taken by South American shamans.

Olaf Blanke, 2002 Nature article: willfully produced OBEs electrical stimulation of the right angular gyrus in temporal lobe of 43-year old epileptic woman.

Andrew Newberg: Buddhist monks meditate, Franciscan nuns pray, brain scans show low activity in the posterior superior parietal lobe, a region of the brain the authors have dubbed the Orientation Association Area (OAA)—orient the body in physical space.

2010 discovery by Italian neuroscientist Cosimo Urgesi: damage to posterior superior parietal lobe through tumorous legions can cause patients to suddenly experience feelings of spiritual transcendence.

Ramachandran: microseizures in the temporal lobes trigger intense religiosity, speaking in tongues, feelings of transcendence.

Why do people believe in the afterlife?

Impossible to conceptualize death, or a world without life

Agenticity: we impart agency and intention to inanimate objects such as rocks and trees and clouds, and to animate objects such as predators, prey

Natural born dualists: corporeal/incorporeal, body/soul, brain/mind

Essentialism: Hitler’s jacket, Mr. Rogers’ sweater, Brad Pitt’s shirt, organ transplants

Theory of Mind (ToM). We project ourselves into the minds of others and imagining how we would feel. ToM occurs in the anterior paracingulate cortex just behind our forehead. We project ourselves into the future.

Extension of our body schema. Our brains construct a body image out of the myriad inputs from every nook and cranny of our bodies, that when woven together forms a seamless tapestry of a single individual called the self that we project into the future.

Extension of our mind schema/Decentering. afterlife is extension of our normal ability to imagine ourselves somewhere else both in space and time, including time immemorial.

Cosmic justice.

Habermas then gave his opening remarks and we went back and forth twice, took questions from the audience, and I ended with this call for us all to live life in this life and not in some imagined next life:

Not Life After Death…Life During Life

Either the soul survives death or it does not, and there is no scientific evidence that it does or ever will. Does this reality extirpate all meaning in life? No. Quite the opposite, in fact. If this is all there is, then how meaningful become our lives, our families, our friends, our communities—and how we treat others—when every day, every moment, every relationship, and every person counts; not as props in a temporary staging before an eternal tomorrow where ultimate purpose will be revealed to us, but as valued essences in the here-and-now where purpose is created by us.

Science tells us is that we are but one among hundreds of millions of species that evolved over the course of three and a half billion years on one tiny planet among many orbiting an ordinary star, itself one of possibly billions of solar systems in a commonplace galaxy that contains hundreds of billions of stars, itself located in a cluster of galaxies not so different from millions of other galaxy clusters, themselves whirling away from one another in an accelerating expanding cosmic bubble universe that very possibly is only one among a near infinite number of bubble universes. Is it really possible that this entire cosmological multiverse was designed and exists for one tiny subgroup of a single species on one planet in a lone galaxy in that solitary bubble universe? It seems unlikely.

Through a natural process of evolution, and an artificial course of culture, we have inherited the mantle of life’s caretaker on Earth, the only home we have ever known. The realization that we exist together for a narrow slice of time and a limited parsec of space, potentially elevates us all to a higher plane of humility and humanity, a provisional proscenium in the drama of the cosmos.

Matthew Arnold, Empedocles on Etna:

Is it so small a thing,

To have enjoyed the sun,

To have lived light in the Spring,

To have loved, to have thought, to have done;

To have advanced true friends, and beat down baffling foes;

That we must feign a bliss

Of doubtful future date,

And while we dream on this,

Lose all our present state,

And relegate to worlds yet distant our repose?

Michael Shermer's Blog

- Michael Shermer's profile

- 1155 followers