Michael Shermer's Blog, page 16

November 1, 2011

Occupy This!

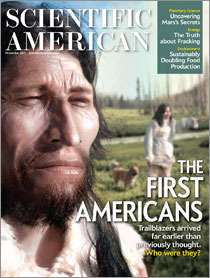

On Sunday morning, October 16, 2011, I taxied down to the Occupy Wall Street shindig from the 92nd Street Y where the Singularity Summit was unraveling as organizers scrambled to figure out how to work the wireless Internet system in the room while speakers boasted about how close we are to computers achieving human level intelligence. Human ignorance maybe, but intelligence? More on that topic later. (See my Scientific American column for January—out mid December—for my skeptical thoughts on when I think computers will achieve human level intelligence. Hint: We're five years away…and always will be. But since I don't want to sound so pessimistic, I have taken a cue from the singer/songwriters Zager and Evans, that the exordium and terminus of the singularity will be 2525 and 9595.)

When I posted some pics I snapped with my iPhone on twitter and made a couple of snide remarks, many of my fellow skeptics chided me for my insensitivity or berated me for my libertarian blindness to real social injustices being protested at the various "Occupy X" events. I call them events (or "shindigs") because my general impression is that although there are some real issues being mentioned here and there in a desultory manner, for the most part I think most people I saw were in one of two categories: (1) onlookers such as myself snapping pictures and taking in the scene; (2) participants wanting to be part of what might turn out to be this generation's (a) Woodstock or (b) Montgomery bus boycott. In my opinion it is neither, but I have to admit that I haven't inhaled that much second-hand pot smoke since I was in college (yes, even at the staunchly conservative Pepperdine University, there were bountiful plumes of pot smoke wafting down the dorm room hallways!).

I have appended various photographs at the end of this essay to let the moment speak for itself, grammatically challenged signs and all, but let me first make a few comments regarding what might be gleaned from the party atmosphere of a few salient points of political and economic significance.

Why has no one from Wall Street gone to jail for the financial meltdown? Bill Maher has asked this question several times on his HBO show Real Time. I have asked many experts myself, including economists, lawyers, and Wall Street traders. Answer: no one went to jail because they didn't break any laws. Conclusion: If you want someone punished for the meltdown you have to first change the law. Perhaps these protests are the first step in that direction, although I doubt it because I don't think Wall Street by itself caused the meltdown. It was a combination of many factors, primary being the removal of risk aversion from both Wall Street traders (and bankers) and Main Street home buyers. Still, if you want to blame Wall Streeters…

What, exactly, did these Wall Street people do that was so wrong? Well, for one, the protestors seem to think that they are too greedy. This is like standing outside the Staples Center in Los Angeles to protest that Kobe Bryant and the Lakers are too greedy because they are constantly trying to win a championship and make a ton of money in the process. That's the whole point of playing professional sports—to win and make a boatload of money in the process! Analogously, the only reason to work on Wall Street is to make a boatload of money. That's the whole point of "playing the market."

The Wall Streeters accepted bailout money that they shouldn't have gotten. Yeah, well, whose fault is that? What did you think they would do? Turn the money down? Heck no! You offer someone a handout and they'll take it, whether it is a main street worker or a Wall Street CEO. The problem is that they should never have been bailed out in the first place. That happened because of crony capitalism, which is nothing like the libertarian vision of real capitalism. So here I'm sympathetic with the Occupy X protestors: no "in profits we're capitalists, in losses we're socialists." Sorry. If you want to play the game of Risk you have to accept the losses as well as the gains.

Wall Street CEOs and their resident COOs, CFOs, traders, and the like, make too damn much money, hundreds of times more than the gap used to be between the highest paid and lowest paid members of corporations. Emotionally I am once again sympathetic to the Occupy Xers: the amount of money some of these guys makes is obscene, and the income gap between them and us is Grand Canyonesque in yawning abyss. But what's the number? How much is too much income? $1 million? $10 million? $100 million $1 billion? $10 billion? Is it really the job of some government agency to set a ceiling on how much anyone is allowed to make? Would any of my readers care to pick a number and defend it? And what if it is a number well under Bill Gates' income? He's giving most of it away to what most of us would consider very worthwhile causes (disease eradication in Africa, education in America). Is it okay to make $X if you give most of it away, or is it only okay if it is taxed away from you and spent on some cause someone else thinks is better than the causes you want to support?

The government should regulate Wall Street more. I agree that all competitions must be regulated by a well-defined set of rules that are consistently enforced with penalties assessed without prejudice or bias, from sporting contests to stock market trading. That is what the SEC is for, among other regulatory bodies. But from where I sit as an average Joe the Skeptic position of modest income who tries his hand at stock market trading in figures infinitesimally smaller than the Big Boys, it all looks like insider trading to me—from the Wall Street CEOs to the Beltway politicians appointed to look after them, who seemingly trade jobs and hold their positions no matter who is in power, Democrats or Republicans. Obama has drunk the Wall Street Kool Aid no less than Bush did. They all do. The entire system is corrupt, in that sense. Once you allow the players to dictate who enforces the rules of the game, the game is over. It would be like Barry Bonds being appointed Director of the Steroid Drug Testing Agency overseeing baseball to insure a fair contest, while he is still playing the game!

Will anything come of the Occupy This protests? Probably not. If the President of the United States can't institute changes, who can? Congress? Yeah, right, there's no corporate money tainting those jobs now is there? So here's one man's simplistic answer: no more government bail outs for anyone for anything, either on Main Street or Wall Street. Bail out money corrupts, and government bail out money corrupts absolutely.

Click a photo to enlarge it

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

The Real Science behind Scientology

IN THE 1990S I had the opportunity to dine with the late musician Isaac Hayes, whose career fortunes had just made a stunning turnabout upward, which he attributed to Scientology. It was a glowing testimonial by a sincere follower of the Church, but is it evidence that Scientology works? Two recently published books argue that there is no science in Scientology, only quasireligious doctrines wrapped in New Age flapdoodle masquerading as science. The Church of Scientology, by Hugh B. Urban, professor of religious studies at Ohio State University, is the most scholarly treatment of the organization to date, and investigative journalist Janet Reitman's Inside Scientology is an electrifying read that includes eye-popping and well-documented tales of billion-year con tracts, aggressive recruitment programs, and verbal and physical abuse of staffers.

The problem with testimonials is that they do not constitute evidence in science. As social psychologist Carol Tavris told me, "Every therapy produces enthusiastic testimonials because of the justification-of-effort effect. Anyone who invests time and money and effort in a therapy will say it helped. Scientology might have helped Isaac Hayes, just as psychoanalysis and bungee jumping might have helped others, but that doesn't mean the intervention was the reason. To know if there is anything special about Scientology, you need to do controlled studies—randomly assigning people to Scientology or a control group (or a different therapy) for the same problem." To my knowledge, no such study has been conducted. The real science behind Scientology seems to be an understanding of the very human need, as social animals, to be part of a supportive group—and the willingness of people to pay handsomely for it.

If Scientology is not a science, is it even a religion? Well, it does have its own creation myth. Around 75 million years ago Xenu, the ruler of a Galactic Confederation of 76 planets, transported billions of his charges in spaceships similar to DC-8 jets to a planet called Teegeeack (Earth). There they were placed in volcanoes and killed by exploding hydrogen bombs, after which their "thetans" (souls) remained to inhabit the bodies of future earthlings, causing humans today great spiritual harm and unhappiness that can be remedied through special techniques involving an Electropsychometer (E-meter) in a process called auditing.

Thanks to the Internet, this story—previously revealed only to those who paid tens of thousands of dollars in courses to reach Operating Thetan Level III (OT III) of Scientology—is now so widely known that it was even featured in a 2005 episode of the animated TV series South Park. In fact, according to numerous Web postings by ex-Scientologists, documents from court cases involving followers who reached OT III and abundant books and articles by ex-members who heard the story firsthand and corroborate the details, this is Scientology's Genesis. So did its founder, writer L. Ron Hubbard, just make it all up—as legend has it—to create a religion that was more lucrative than producing science fiction?

Instead of printing the legend as fact, I recently interviewed the acclaimed science-fiction author Harlan Ellison, who told me he was at the birth of Scientology. At a meeting in New York City of a sci-fi writers' group called the Hydra Club, Hubbard was complaining to L. Sprague de Camp and the others about writing for a penny a word. "Lester del Rey then said half-jokingly, 'What you really ought to do is create a religion because it will be tax-free,' and at that point everyone in the room started chiming in with ideas for this new religion. So the idea was a Gestalt that Ron caught on to and assimilated the details. He then wrote it up as 'Dianetics: A New Science of the Mind' and sold it to John W. Campbell, Jr., who published it in Astounding Science Fiction in 1950." To be fair, Scientology's Xenu story is no more scientifically untenable than other faith's origin myths. If there is no testable means of determining which creation cosmogony is correct, perhaps they are all astounding science fictions.

October 31, 2011

Social Singularity: Why Things Are Getting Progressively Better

Michael Shermer discusses the problem of tribalism, which we inherited from our primate ancestors, and which we must overcome if we are to achieve a stable and just global society. This lecture was recorded on October 15, 2011 at the 2011 Singularity Summit in New York.

October 25, 2011

Transhumanism, the Singularity and Skepticism

Michael Shermer is interviewed about his views on the future of Artificial Intelligence, the technological singularity, transhumanism, and skepticism. This is not something that Michael Shermer usually talks about. Michael also spoke at the Singularity Summit in the US this year (2011). This footage was taken at the 2011 Think Inc conference in Melbourne.

October 18, 2011

The Flake Equation

experienced the paranormal or supernatural

The Drake Equation is the famous formula developed by the astronomer Frank Drake for estimating the number of extraterrestrial civilizations:

N = R × fp × ne × fl × fi × fc × L where…

N = the number of communicative civilizations,

R = the rate of formation of suitable stars,

fp = the fraction of those stars with planets,

ne = the number of earth-like planets per solar system,

fl = the fraction of planets with life,

fi = the fraction of planets with intelligent life,

fc = the fraction of planets with communicating technology, and

L = the lifetime of communicating civilizations.

The equation is so ubiquitous that it has even been employed in the popular television series The Big Bang Theory for computing the number of available sex partners within a 40-mile radius of Los Angeles (5,812). My favorite parody of it is by the cartoonist Randall Munroe as one in a series of his clever science send-ups, entitled "The Flake Equation" (on xkcd.com) for calculating the number of people who will mistakenly think they had an ET encounter.

Such multiplicative equations for calculating the product of an increasingly restrictive series of fractional values are effective tools for making back-of-the-envelope calculations to solve problems for which we do not have precise data. To that end I thought it a useful addition to the Skeptic toolbox to create a Flake Equation for all paranormal and supernatural experiences (and in the Flake Equation I'm interested not in beliefs but in actual experiences that people report and that we hear about, because this becomes the foundation of paranormal and supernatural beliefs):

N = Pw × fp × fm × ft × nt × no × fm where…

N = Number of people we hear about who report having experienced a paranormal or supernatural phenomena,

Pw = Population of the United States (January 1, 2012: 312,938,813),

fp = Fraction of people who report having had an anomalous psychological experience or witnessed an unusual physical phenomena (1/5),

fm = Fraction of people who interpret such experiences and phenomena as paranormal or supernatural (1/5),

ft = Fraction of people who tell someone about their experience (1/10),

nt = Number of people they tell (15),

no = Number of other people told the story by original hearers (15), and

fm = Fraction of such stories reported in the media or on Internet blogs, tweets, and forums (1/10).

N = 28,164,493, or about 9 percent of the U.S. population.

To compute this figure I used the 2005/2007 Baylor Religion Survey, which reports that

23.2% say that they have "witnessed a miraculous, physical healing,"

16.3% "received a miraculous, physical healing,"

27.5% "witnessed people speaking in tongues at a place of worship,"

7.7% "spoke or prayed in tongues,"

54.5% experienced being "protected from harm by a guardian angel,"

5.9% "personally had a vision of a religious figure while awake,"

19.1% "heard the voice of God speaking to me,"

26.1% "had a dream of religious significance,"

52% "had an experience where you felt that you were filled with the spirit,"

22.1% "felt at one with the universe,"

25.7% "had a religious conversion experience,"

13.8% "had an experience where you felt that you were in a state of religious ecstasy,"

14.2% "had an experience where you felt that you left your body for a period of time,"

40.4% "had a dream that later came true," and

16.7% "witnessed an object in the sky that you could not identify (UFO)."

This works out to an average of 24.4 percent, thereby justifying my conservative 20 percent figure for fp and fm. The other numbers I gleaned from research on gossip and social networks, conservatively estimating that 10 percent of people will tell someone about their unusual experience, and that within their average social network of 150 people they will tell at least 10 percent of them (15) who in turn will pass on the story to 10 percent of their social network of 150 (15). Finally, I estimate that 10 percent of such stories will be reported in the media or recounted in blogs, tweets, forums, and the like.

Of course the final figure for N will vary considerably depending on what numbers are plugged into the equation, but the result will almost always be a number in the tens of millions, which goes a long way toward explaining why belief in the paranormal and supernatural is so ubiquitous. Experiencing is believing!

October 15, 2011

The Decline of Violence

[image error]

ON JULY 22, 2011, a 32-year old Norwegian named Anders Behring Breivik opened fire on participants in a Labour Party youth camp on the island of Utoya after exploding a bomb in Oslo, resulting in 77 dead, the worst tragedy in Norway since World War II.

English philosopher Thomas Hobbes famously argued in his 1651 book, Leviathan, that such acts of violence would be commonplace without a strong state to enforce the rule of law. But aren't they? What about 9/11 and 7/7, Auschwitz and Rwanda, Columbine and Fort Hood? What about all the murders, rapes and child molestation cases we hear about so often? Can anyone seriously argue that violence is in decline? They can, and they do—and they have data, compellingly compiled in a massive 832-page tome by Harvard University social scientist Steven Pinker entitled The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (Viking, 2011). The problem with anecdotes about single events is that they obscure long-term trends. Breivik and his ilk make front-page news for the very reason that they are now unusual. It was not always so.

Take homicide. Using old court and county records in England, scholars calculate that rates have "plummeted by a factor of ten, fifty, and in some cases a hundred—for example, from 110 homicides per 100,000 people per year in 14th-century Oxford to less than 1 homicide per 100,000 in mid-20th-century London." Similar patterns have been documented in Italy, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Scandinavia. The longer-term trend is even more dramatic, Pinker told me in an interview: "Violent deaths of all kinds have declined, from around 500 per 100,000 people per year in prestate societies to around 50 in the Middle Ages, to around six to eight today worldwide, and fewer than one in most of Europe." What about gun-toting Americans and our inordinate rate of homicides (currently around five per 100,000 per year) compared with other Western democracies? In 2005, Pinker computes, just eight tenths of 1 percent of all Americans died of domestic homicides and in two foreign wars combined.

As for wars, prehistoric peoples were far more murderous than states in percentages of the population killed in combat, Pinker told me: "On average, nonstate societies kill around 15 percent of their people in wars, whereas today's states kill a few hundredths of a percent." Pinker calculates that even in the murderous 20th century, about 40 million people died in war out of the approximately six billion people who lived, or 0.7 percent. Even if we include war-related deaths of citizens from disease, famines and genocides, that brings the death toll up to 180 million deaths, or about 3 percent.

Why has violence declined? Hobbes was only partially right in advocating top-down state controls to keep the worse demons of our nature in check. A bottom-up civilizing process has also been under way for centuries, Pinker explained: "Beginning in the 11th or 12th [century] and maturing in the 17th and 18th, Europeans increasingly inhibited their impulses, anticipated the long-term consequences of their actions, and took other people's thoughts and feelings into consideration. A culture of honour (the readiness to take revenge) gave way to a culture of dignity (the readiness to control one's emotions). These ideals originated in explicit instructions that cultural arbiters gave to aristocrats and noblemen, allowing them to differentiate themselves from the villains and boors. But they were then absorbed into the socialization of younger and younger children until they became second nature."

That second nature is expressed in the unreported "10,000 acts of kindness," as the late Stephen Jay Gould memorably styled the number of typically benevolent interactions among people for every hostile act. This is the glue that binds us all in, as Abraham Lincoln so eloquently expressed it, "every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land" through "the mystic chords of memory" that have been touched again by these better angels of our nature.

October 5, 2011

The Nightline Face-off: Does God Have a Future? Deepak Chopra v. Michael Shermer

Science and faith do battle as archrivals Michael Shermer and Deepak Chopra debate in this ABC Nightline Face-off from March 2010. This video has 12 parts. You can click to the next part at the end of each part.

You can also watch the debate on ABCNews.

September 27, 2011

The Mystic Chords of Violence's Memory

This is a review of The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, by Steven Pinker

(October 2011, Viking. 771 pages. ISBN 978-0-670-02295-3). Originally published in the Autumn issue of The American Scholar as "Getting Better All the Time."

In The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, John Ford's classic 1962 film, a clash of moral codes unfolds in the wild-west frontier town of Shinbone, Arizona. I call these moral codes the Cowboy Code, where disputes are settled and justice is served between individuals who have taken the law into their own hands, and the Law Code, where disputes are settled and justice is served between all members of the society who, by virtue of living there, have tacitly agreed to obey the rules. The Cowboy Code is represented by John Wayne's character, Tom Doniphon, a fiercely loyal and deeply honest gunslinger duty-bound to enforce justice on his own terms through the power of his presence backed by the gun on his hip. The Law Code is embodied by Jimmy Stewart's Ransom Stoddard, an attorney hell bent on seeing his beloved Shinbone make the transition from cowboy justice to the rule of law. Lee Marvin's Liberty Valance is a coarse highwayman who respects only one man, Tom Doniphon, because they share the Cowboy Code that men settle their disputes between themselves. Despite Valance's constant taunting of the law, Stoddard holds to his belief that until Valance is caught doing something illegal there can be no justice. When Doniphon tells Stoddard "You better start pack'n a handgun," Stoddard rejoins, "I don't want to kill him. I just want to put him in jail." At long last, however, Stoddard decides to take Doniphon's advice that "out here a man settles his own problems," and turns to him for gun-fighting lessons. When Valance challenges Stoddard to a dual, the overconfident naïf accepts and a late-night showdown ensues. In a darkened street, the two men square off. Stoddard is trembling in fear while Valance mocks and scorns him, shooting first too high and then too low. When Valance takes aim to kill, Stoddard shakily draws his weapon and discharges it. Valance collapses in a heap. Having felled one of the toughest guns in the west Stoddard goes on to become a local hero, building that image into political capital and working his way up from local politics to a distinguished career as a United States Senator.

So it would appear that the Law Code prevailed over the Cowboy Code, but not so fast. In the end we learn that the man who shot Liberty Valance was Tom Doniphon. Knowing that Stoddard was no match for Valance, in a flashback replay of the dual from another perspective we see Doniphon lurking in the shadows and fingering a rifle, which he engaged to kill Valance at the crucially-timed moment when the two men drew their weapons. Holding to the Cowboy Code of loyalty, Doniphon takes the secret to his grave.

The fictional Shinbone embodies any small community in transition from an informal to a formal moral code and system of justice. When everyone takes the law into their own hands there is no law, and thus the opportunities for unchecked violations of informal codes expands exponentially as populations increase, leading to an increase in violence and requiring the creation of such social technologies as codes, courts, and constitutions. The transition from the informal rule of frontier justice found in pre-modern societies to the formal rule of law pervasive throughout modern democratic nations is a result of the creation of a myriad of political and economic systems and legal and moral codes that together have led to a systematic decline of violence in what the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker calls "the civilizing process" in his book The Better Angels of Our Nature. The title comes from Abraham Lincoln's Inaugural Address on March 4, 1861, as America was about to fall into anything but a civilizing process of civil war (so his memorable words are more prescriptive than descriptive):

The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

Four years and 600,000 dead later, our better angels finally emerged. Or did they? What about the First and Second World Wars, not to mention the Holocaust, Stalin's purges, Mao's cultural revolution, Cambodia's killing fields, and the numerous genocides in Africa? With bodies stacked like cordwood and the ashes in the crematoria still cooling in living memory, how can anyone seriously argue that there has been a decline in violence? Because, Pinker demonstrates through compelling anecdotes and copious charts, long-term data trumps recent anecdotes. The idea that we live in an exceptionally violent time is an illusion created by the media's relentless coverage of violence, coupled to our brain's evolved propensity to notice and remember recent and emotionally salient events, of which violence plays second fiddle to no one. Unfortunately, our brains did not evolve to carefully track long-term trends, and thus it is that evolution, along with climate change and other historical sciences, seems counterintuitive. And Pinker's thesis is nothing if not counterintuitive: that violence of all kinds—from murder, rape, and genocide to parents spanking their kids to the treatment of blacks, women, gays, and animals—has been in decline for centuries as a result of this civilizing process.

Picking up Pinker's 771-page magnum feels daunting, but it's a page-turner from the start as he reminds us through literary anecdotes of what life was like in the foreign country known as the past. To wit, Homer's Agamemnon explains to King Menelaus his war strategy: "We are not going to leave a single one of them alive, down to the babies in their mothers' wombs—not even they must live. The whole people must be wiped out of existence, and none be left to think of them and shed a tear." The Bible (the "Good Book"), Pinker reminds us, "depicts a world that, seen through modern eyes, is staggering in its savagery. People enslave, rape, and murder members of their immediate families. Warlords slaughter civilians indiscriminately, including the children. Women are bought, sold, and plundered like sex toys. And Yahweh tortures and massacres people by the hundreds of thousands for trivial disobedience or for no reason at all." In fact, the book opens with a murder. After creating the heavens and the earth and Adam and Eve and their two boys Cain and Able, the former killed the latter. "With a world population of exactly four," Pinker notes, "that works out to a homicide rate of 25 percent, which is about a thousand times higher than the equivalent rates in Western countries today."

Pinker is not being flippant. A graph in the next chapter, for example, presents the data from dozens of studies revealing the percentage of deaths in warfare from prehistoric times to present. The contrast is striking: Prehistoric peoples and modern hunter-gatherers and hunter-horticulturalists are far more murderous than states, with percentages for the former ranging from 10 to 60 percent and an average of 24.5 percent compared to 5 percent and under for the latter. Even the bloody 20th century wars weren't so bloody by comparison: About 40 million people died in battle deaths during the century in which around six billion people lived, which amounts to 0.7 percent battle deaths. What about noncombat deaths, such as all those citizens who became the collateral damage of war? "Even if we tripled or quadrupled the estimate to include indirect deaths from war-causes famine and disease, it would barely narrow the gap between state and nonstate societies," Pinker retorts. What about all those genocides and the Holocaust? That brings the death toll up to 180 million deaths, which "still amounts to only 3 percent of the deaths in the 20th century." What about the 21st century? In 2005, Pinker computes, a grand total of 0.008, or eight tenths of one percent of Americans died in two foreign wars and domestic homicides combined. In the world as a whole, the rate of violence from war, terrorism, genocide, and killings by warlords and militias was 0.0003 of the total population, or three hundredths of one percent.

The numbers go on and on like this for hundreds of pages, punctuated by poignant anecdotes that drive home the point that things really are getting better and that these are the good old days. Readers of this book, Pinker reminds us, "no longer have to worry about abduction into sexual slavery, divinely commanded genocide, lethal circuses and tournaments; punishments on the cross, rack, wheel, stake, or strappado for holding unpopular beliefs, decapitation for not bearing a son, disembowelment for having dated a royal, pistol duels to defend their honor, beachside fisticuffs to impress their girlfriends, and the prospect of a nuclear world war that would put an end to civilization or to human life itself." You can, of course, think of a few exceptions here and there, but that's the point: what used to be commonplace is now rare, and in most of the above examples, nonexistent. Why?

Science is a three-legged stool of data, theory, and communication. Having convinced readers that violence is in decline through data well communicated, Pinker devotes the rest of his tome to his theory that the better angels of our nature are brought out by the civilizing process of two forces: the top-down rule of law and the bottom-up rule of morals. More generous than most scholars in crediting others' work, Pinker's grounds his theory in the Jewish historian Norbert Elias's 1939 book The Civilizing Process, a catalogue of examples from the archives of history demonstrating that over the centuries, "beginning in the 11th or 12th and maturing in the 17th and 18th, Europeans increasingly inhibited their impulses, anticipated the long-term consequences of their actions, and took other people's thoughts and feelings into consideration. A culture of honor—the readiness to take revenge—gave way to a culture of dignity—the readiness to control one's emotions. These ideals originated in explicit instructions that cultural arbiters gave to aristocrats and noblemen, allowing them to differentiate themselves from the villains and boors. But they were then absorbed into the socialization of younger and younger children until they became second nature."

Second nature. Our first nature is to be selfish, greedy, and nasty. Our second nature—the better angels of our nature—requires a little coaxing and persuading to come out. Analysis of medieval books of etiquette, for example, reveal that the numerous prohibitions are reducible to a few principles related to this second nature, as Pinker notes: "Control your appetites; Delay gratification; Consider the sensibilities of others; Don't act like a peasant; Distance yourself from your animal nature. And the penalty for these infractions was assumed to be internal: a sense of shame." Externally, other forces were at work along the lines of what I described in the shift from the Cowboy Code to the Law Code. These include, in Pinker's words, "the centralization of state control and its monopolization of violence, the growth of craft guilds and bureaucracies, the replacement of barter with money, the development of technology, the enhancement of trade, the growing webs of dependency among far-flung individuals," and the like.

Again—and it must be repeated in every discussion of this controversial topic—the decline of violence is tracked in a systematic sloping downward curve with occasional bumps along the way. Think of a saw blade tilted down at an angle. Individual teeth point upward, but the overall slope of the blade is downward. Or think global warming. Yes, some years are cooler—and climate deniers are only to happy to point them out—but the overall trend is that of a warming earth. The analogy applies to violence of all kind. Compared to 500 or 1000 years ago, today a greater percentage of people in more places more of the time are safer, healthier, wealthier, and freer. With the recent ascendency of the Tea Party movement and the media coverage of angry white men, liberals understandably believe that things are grim and getting worse. But, in fact, Pinker notes that "in every issue touched by the Rights Revolutions—interracial marriage, the empowerment of women, the tolerance of homosexuality, the punishment of children, and the treatment of animals—the attitudes of conservatives have followed the trajectory of liberals, with the result that today's conservatives are more liberal than yesterday's liberals."

This is a shift to be celebrated, even as we honor the principle of that other great American President, Thomas Jefferson, that eternal vigilance is the price of freedom.

September 19, 2011

The Believing Brain lecture at the University of Melbourne

In this talk (recorded at the Copland Theatre, University of Melbourne on 19 September 2011) Dr. Michael Shermer presents his comprehensive and provocative theory on how humans form beliefs and reinforce them as truths. He answers the questions of how and why we believe what we do in all aspects of our lives, from our suspicions and superstitions to our politics, economics and social beliefs.

September 14, 2011

"You've Got…" on AOL

Skeptic magazine editor Michael Shermer discusses why people are often duped…

Michael Shermer's Blog

- Michael Shermer's profile

- 1155 followers