Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 23

February 17, 2020

Two Still Lives

View full screen for best effect.

In the past couple of weeks, I've been trying out some semi-professional video editing programs, and learning to use their various features. I finally settled on Filmora9 for the time being; it has all the features I've wanted, with a good interface and help menus, and a not-too-steep learning curve.

One of the things I've wanted to do is to create videos using still images, either combined with actual video footage, or not, that have "camera motion" added in the editing process -- the so-called "Ken Burns effect" which actually entails a whole set of decisions involving different motions, transitions, durations, and edits. Here's my first publishable effort -- and obviously it doesn't have a sound track, that's another whole area to learn about. (Dave Bonta, I'm thinking of you and your moving poems, and all the work that's gone into them over the years.)

Video creation and editing are a lot of fun, and the perfect, picky sort of work that I like. This is something I've wanted to do for years. It should be a help for Phoenicia, for my own artwork, and for various organizations I'm involved with. The second project I've been working on is a five-minute loop of photographs J. took at the Montreal Climate March this past fall, which he'll be showing at the cathedral during Nuit Blanche on February 29, and I'll see if I can post that here after the event.

February 12, 2020

Goodbye, Mini

The life of one of our dearest feline friends is ending today. The Mini has lived with Ed and Martine for fifteen years, so we've known him almost as long as we've known them. They were two of our first friends in Montreal -- we met through our blogs even before we moved up here, and have stayed close ever since. Our shared love of cats is one of the things we have in common, and we've both taken care of each other's cats during vacations. I always liked to watch and to draw Mini, who is totally black, muscular and male, and thus totally different from our small three-colored Manon. When we have dinner at Ed and Martine's place, Mini usually hangs around and seems to recognize us, and he often gets up in one of the chairs and "sits" with us during the meal, his little face peering over the edge of the table as if he's another person with his own place. He's just a great cat, with a big personality.

But he's been sick for a while now, and the time had come for his humans to make the hard but kindest decision. His life will end at home, he'll be at peace, and we will start the process of missing him, and remembering him. My heart goes out to Ed and Martine today.

February 5, 2020

The Life of Flowers

In these days when everything human beings are doing seems so screwed up, here's something truly beautiful, both in the animation artwork and the miracle of what it's showing. Enjoy.

January 31, 2020

A Black Letter Day

Antikyra, Greece.

I just skimmed through the Guardian and the New York Times – I can only spend 15-30 minutes on the Times, in particular, or I get too depressed – and my husband asked, from the kitchen, “what are all those sighs?” It’s unbelievable, what’s going on, and the place that both the U.S. and the U.K. have come to, not to mention the world and climate change. And it’s difficult for me, sometimes, to understand my own life in this context. Everything I've based my life on and care about deeply feels irrelevant, and, at the same time, endangered.

I think it’s imperative that we try to talk about this aspect of being alive now, not just the issues that we’re all so concerned about and which are affecting us nearly every minute of every day. So many of us are living with grief, pain, and helplessness, plus we’re being fed a steady diet of anxiety, but the message given by capitalism, advertising, entertainment, and even many of our spiritual and educational institutions, is to carry on as usual: don’t talk too much about it, do your work, shore up your own future, play with your friends and family, pretend this isn’t happening as long as you possibly can. Unfortunately, most people in leadership positions have little idea how to talk about such a dire psychological crisis. And in the U.S., the denial of interconnection of all the major issues in the world has reached epic proportions. Today we read that Greece is building a floating migrant barrier. It’s horrible, but far more understandable to me than a wall on the southern U.S. border. Greece and Italy have borne the brunt of the refugee crisis for all of Europe and the rest of the world, while the richer countries have set quotas and washed their hands. And America has the gall to criticize Greece? Or refuse to acknowledge whose policies have caused the terrorism and refugee crises in the first place? How can people be capable of such hypocrisy and poor thinking? And that’s just one part of the whole interconnected mess.

So we have a probable impeachment acquittal and Brexit coming on the same day. An American who I love very much recently said to me, “This country is really booming!” They meant it, and believe it. It's as if what that person sees, and what I see, are two entirely different views of reality.

As friends who share similar views, however, we have to find ways to talk to each other, and help each other not to be crushed by the weight of grief and anxiety about the future, our sense of the sheer wrongness of what is going on, and our utter fatigue at the rigidity of the current moral divisions in society. It’s extremely difficult. If you focus on your own personal life, or on pursuits like art, for instance, it can feel like putting your head in the sand even though those pursuits are vitally important for lifting the spirit. Writing about what is wrong can be cathartic, and make us feel like we’re doing something, but does it actually do any good when no one is willing to change their mind? Is there anything truly useful that any of us can do against these sorts of forces, other than doing our best to try to change the political leadership?

I think of people in concentration camps, or civilians caught up in wars. We in the privileged West are not being literally bombarded by explosive weapons, but we are being bombarded emotionally and psychologically every single day. We are not literally imprisoned in concentration camps, but we are actually imprisoned in a situation that is doing violence to innocent people and to the earth as we watch, and this situation of being a constant witness is draining and depleting to the point of paralysis, no matter how secure we are, how much money we give, or how many changes we make in our own lifestyles.

So I also remember the importance of people who have kept hope alive in the past, and who kept LIFE alive, by living as fully, joyfully, lovingly, non-violently, and wisely as possible while being absolutely clear about what was, in fact, happening. As Thomas Merton wrote, we need to become people who can hold the darkness and the light in our hands simultaneously. This is only possible through contemplation and a great deal of thought and inner work, but that is part of the work we are being called to do.

The other part of the work is to band together to take collective action -- together we can accomplish much more than as individuals, and we can do more to help one another through this extremely challenging period of time. Do something. Help build a house for someone who can't afford it. Work collectively to force institutions to divest of fossil fuels. Sponsor a refugee family. Send aid to imprisoned Hispanic children. Teach. Bring art and music into other people's lives. Start a group where thinking, caring people like you can discuss the challenge of being alive right now. Turn your own despair into someone else's hope.

January 25, 2020

Caryatids, and an Olive Tree

My favorite site on the Acropolis is not the Parthenon, but the porch of a much smaller temple called the Erechtheum. I've been fascinated by the graceful women, holding the roof on their heads, since I first saw pictures of them almost half a century ago. When we visited in 2018, I kept looking at it from different angles, first from far and then walking close and around the building, unable to let it out of my sight for long.

A recent pen and ink sketch of mine.

This single olive tree marks the site where, according to the legend immortalized on the western pediment of the Acropolis, Poseidon and Athena competed for patronage of the city. Poseidon struck his trident against the rock of the Acropolis, and a salt spring came forth. But Athena planted an olive tree, and won the contest and the hearts of the people. Supposedly, an olive tree has always stood there, each successive one propagated from branches of its predecessor. I'm sure that's not entirely true. Somewhere nearby, a mark in the rock supposedly shows where Poseidon struck it (!)

Athena and Poseidon square off (replicas of the Acropolis pediments, Acropolis Museum, Athens)

Athena is crowned victorious next to her father Zeus, while the other gods look on.

Pericles ordered the Erechtheum to be built as part of the splendid rebuilding of the damaged Acropolis after the Persian invasion (480 BCE) that included the construction of the Parthenon. The Erechtheum was built of shining white Pentelic marble, and named after Erechtheus, an early, mythical, demi-god king of Athens. It was begun in 421 during a peaceful period, but halted after war began with Sparta, and only finally completed in 406 -- the last of these major buildings to be finished.

The Parthenon frieze shows the Panathenaic procession: in this segment, two figures hold the folded peplos, a new robe being carried up to the statue of Athena.

The temple was one of the holiest places for the Athenians. Inside was placed the ancient olivewood statue of Athena that was clothed in a new, specially-woven robe every four years, carried up to the Acropolis in the Panathenaic procession -- a statue that retained its historic, cult status even though a huge crystal and gold statue of Athena had recently been placed in the rebuilt Parthenon. A sacred serpent, said to be a reincarnation of Erechtheus, lived in one of the western chambers of the temple, and was fed on honey cakes. If the snake refused to eat the cakes, it was considered a very bad omen.

The scale of the Erectheum (far right) compared to the Parthenon.

The robed women on the Erechtheum's porch strike me as both beautiful and enigmatic -- there's something personal and almost intimate about them, especially in the context of the grandeur and immensity of the Parthenon. The Roman architect Vitruvius first used the term Caryatid: he said it refers to a town called Caryae in the Peloponnesus which sided with the Persians against Greece; after the war, the Greeks retaliated against Caryae, killing the men and enslaving the women. "The architects of the time," he writes, "designed for public buildings statues of these women, placed so as to carry a load, in order that the sin and punishment of the people of Caryae might be known and handed down even to posterity."

An archaic kore, statue of a standing, draped female figure at the Altes Museum in Berlin.

It seems plausible, considering the historical time when the Erechtheum was built, but there were many earlier examples of young, draped female figures being used as columns, from the korai of Archaic times to some of the treasuries at Delphi. And the Caryatids look anything but burdened -- part of their charm is how graceful and light they appear.

Restoration work on the caryatids in progress, 2018.

The Erechtheum's statues, of course, attracted the attention of Lord Elgin during his plunder of the Acropolis. In the early 1800s he removed one to his manor in Scotland - she is now in the British Museum - and bungled the removal of another which he had sawn into pieces. Eventually, the remaining statues were removed from the porch and placed in the old Acropolis Museum; recently they were moved to the new Acropolis Museum, where they've been cleaned and restored in place, in a process that could be observed by visitors. Obviously the statues we see today on the porch of the Erechtheum are reproductions, but they're still very beautiful. The five originals, in the museum, are placed exactly as they were on the porch, with a blank for the missing one which Greece still hopes one day will be returned.

The Acropolis Museum is one of the finest museums I've ever visited; no one who saw the state of the art of display and preservation there could argue that the Greeks are "not capable" of taking care of their own monuments, or protecting them from pollution. Probably the Elgin marbles have been better preserved by being in the British Museum over the last 200 years, but that is no longer a question; will the 21st century see the return of cultural artifacts taken by colonial powers, or will imperialist arguments continue to prevail?

January 21, 2020

Winter Sketching, Inside

I recently installed a new photo organizer on my computer, and when looking through the pictures from the last year, I realized I hadn't posted a number of interior drawings because I've been so focused on Mediterranean landscapes. So here's a catch-up post with some of those, appropriate, maybe, for the frigid days we're having here in Montreal that are keeping me mostly inside.

The watercolor and ink sketch, above, was an online gift for a friend who deserved a bouquet. The flowers were the last begonias from our terrace.

I'm inordinately fond of the little ribbed-glass salt dish in the lower right of that pictures: it came from my grandfather, and I think it has a personality, as well as almost always being somewhere on our table. Here it is again in a drawing of a late fall bouquet, some dahlias I picked just before the first frost. That's my father-in-law's Egyptian tambourine on a shelf in the right center back of the room.

Another late fall still life, below, with gourds that were a present from our friends S. and G.

Before going away this past fall, I did a number of sketches with ink and gouache on toned paper, while deciding which sketchbooks to take. Here are two of the same subject - one just in ink, done with a bent-nib fude pen, and the other with some added gouache and watercolor.

and a detail:

and here's the one with some color. I like the sketchbook page with all the scribbles and pen tests at the top.

Finally, here's a gouache still life done not at home, but at the studio, of objects sitting on my desk there. Driftwood, stones, shells, bones, old glass, two jugs that used to hold my mother's paintbrushes...

and another detail:

Which of these resonate the most with you?

January 14, 2020

A Byzantine angel, and where she came from

Hosios Loukas Monastery

During the past two years, we've visited several very old Orthodox monasteries in Greece. The most famous of them all, Mt Athos, is closed to women, so that was not a possibility, but we went to the mind-blowing clifftop monasteries at Meteora, which I'll write about here someday, and the Vlatadon monastery in Thessaloniki, founded on the site where St. Paul is thought to have preached. During this past trip, we visited the abandoned Byzantine city of Mystras in the Peleponnese, near Sparta, which contains a number of no-longer-used churches and monasteries, and the still-viable 10th century walled monastery of Hosios Loukas, located not far from Delphi on a remote mountainside north of the Gulf of Corinth. Our interest is not only in Byzantine art, but the fact that much of it was made during a brief but extraordinary period of cross-cultural flowering, when Greeks, Arabs, Italians and Normans co-mingled in this part of the Mediterranean. Much of Greece feels like it is still looking east, toward Constantinople and the early seat of the Eastern Church. Arab craftsmen often built parts of these structures, and it's not unusual to see Arabic calligraphy alongside Christian mosaics, or eastern domes, vaults, and arches, pierced-stone windows and elaborate tilework in Christian sanctuaries.

That's Peter on the left, and Paul on the right. Where the mosaics come alive the most is in portraiture -- saints, apostles, martyrs, monks, abbots, and church benefactors are shown in roundels or full-length portraits, with unique faces: you can always identify Peter, or Paul, for instance. The most dramatic portrait in many churches is the immense Christ Pantocrator, usually in the central dome or the half-dome over the apse: a depiction of Christ "the All-powerful" in a particular gesture and attitude that, in the most compelling renditions, appears to be looking straight into your soul. This one is on a wall and seems less striking.

My Christmas print this year was inspired by a mosaic from this monastery. That mosaic (upper picture, top right) was golden and glittery, but I was taken by the archangel's hairstyle and the clever way the artist had fit the portrait into the circle, and thought it could be simplified for a linocut. I gave the angel a longer face and made her gender definitely female, changed the staff into more of a wand with stars, and added floral corner motifs inspired by another ceiling, shown below.

The amount of decoration in these Byzantine monasteries and churches defies description. Every surface is decorated in some way, giving the visitor and monk alike endless things to look at, but somehow a harmonious whole is often created. In this church we were intrigued by the amount of faux painting, imitating patterned marble blocks of alternating color -- maybe a Medieval cost-saving measure.

A mosaic floor.

More faux painting, with very free, almost calligraphic brushwork.

I've come to appreciate the tilework on the floors, the painted, inlaid, or carved decorations on walls and pillars, the stylized, often naive depictions of scenes from the Old Testament and the lives of Christ and the apostles, and the technical achievement of creating these stories in the medium of mosaic.

I was quite taken with the one above, showing Jesus being baptized by John in the Jordan River. Isn't the water great? The inscription above reads "H βαπτη", "the Baptist".

And here's Jesus washing Peter's feet at the Last Supper.

These churches are filled with the smell of beeswax from the long handmade tapers that are always burning, and available in graduated sizes for you to light and place in large bowls or trays of fine sand, and the scent of myrrh, the holiest of incenses, which is burned in copious amounts, but also said to exude from the bodies of buried martyrs and saints, or from the springs of water that flow near them. And the churches always have martyrs and founding saints buried in them, their skulls often removed and placed in silver reliquaries, and devout worshippers kneeling in prayer beside the tombs, or affectionately brushing them with their fingers as they pass by, crossing themselves. Ancient icons behind glass or plexi show the marks of thousands of kisses by the faithful, who make the rounds of each sanctuary, kissing and praying before each icon in turn, as a cantor intones hours of chant.

The tomb of the monastery's founder, Luke (not the evangelist), was originally in the crypt, but his bones now lie in the tiny glass-topped coffin shown above, in a passage between the two churches on the site. Luke, known as a great healer, levitator, and worker of miracles, died in February 953, and for centuries afterward, pilgrims came to be healed by "incubation," which meant that they slept in the main church building (katholikon) or in the crypt near his tomb, breathing the scent of the myrrh, being exposed to the oil from the lamp above, and experiencing dreams in which the saint would appear and tell them what they needed to do to be healed. I found this practice particularly fascinating, because earlier in the trip we had also been to the 5th century BC Shrine of Asclepias at Epidaurus, where pilgrims did pretty much the same thing -- sleeping in the katholikon, among holy snakes that slithered on the floor, and experiencing dreams whose healing instructions were interpreted by pagan priests.

Most of the monasteries are much quieter than the Orthodox churches in the cities; in order to stay viable, they are open a few days per week to tourists, but the monks stay mostly out of sight. It's possible to see into their lives a bit, though -- there are herb and vegetable gardens and pens where chickens cluck and peacocks cry; goats and other small animals like rabbits; fruit trees; grape arbors, and, of course, a large grove or even a hillside of olive trees. The monk's cells are located in a particular building, along with a refectory (dining area) that can sometimes be glimpsed and more often not. In a corridor or cloistered walkway, there is usually a rustic iron gong or bell that summons the monks to prayer. Here we entered a former stable (now an art gallery), saw the ancient cider- and wine-presses, and a cemetery with the tombs of recent abbots. In the small shop visitors can buy food products made by the monks as well as icons, candles, incense, local herbs and ointments.

And everywhere we went, there were cats. As Hosias Loukas, near the ancient cider press, these yellow feral cats hid under a pomegranate tree, but were curious enough to let me take their picture. I sometimes felt like the ever-present cats, which seems quite well-fed, contented, and used to humans, were stand-ins for the invisible monks, showing us that daily life continues among these ancient stones.

January 2, 2020

Thoughts for the New Year

In November, I walked through the ancient agora of Athens, the "birthplace of democracy", and tried to imagine the thinkers and politicians, playwrights and artists, and countless ordinary people -- citizens and slaves, Greeks and foreigners -- whose feet had walked these same paths, and seen the same vistas.

Of course, that was 2,500 years ago; it's now a ruin. Athenian democracy fell, but its ideals and principles were taken up again in the Enlightenment, forming the basis for its modern form. Yet, on the cusp of 2020, many of us are wondering where our so-called democracies are headed. No political system lasts forever. Most of us were taught that it was the defeat of Athens by Sparta at the end of the Peloponnesian Wars (404 BC) that caused the end of Athenian democracy. Cambridge classical historian Dr. Michael Scott disagreed; he wrote that Athens actually recovered from that defeat, but that democratic ideals irrevocably crumbled later, during the 4th century BC. He says that Athenian democracy fell because of an economic downturn, unpopular foreign wars, and a surge in immigration - a situation very similar to what western democracies face today.

In an effort to remain a major player in world affairs, it abandoned its ideology and values to ditch past allies while maintaining special relationships with emerging powers like Macedonia and supporting old enemies like the Persian King. This "slippery-fish diplomacy" helped it survive military defeats and widespread political turbulence, but at the expense of its political system. At the start of the century Athens, contrary to traditional reports, was a flourishing democracy. By the end, it was hailing its latest ruler, Demetrius, as both a king and a living God.

When people are afraid, they put their faith in demagogues: it's been true forever.

And when the economy is bad, they sell their most valuable assets to foreign investors. (In 2019, Greece concluded a longterm rental of its port, Piraeus, to China, thereby giving Chinese goods a valuable, nearly permanent entry point into the EU. But this is far from the only example.)

Ultimately, the city was to respond positively to some of these challenges. Many of its economic problems were gradually solved by attracting wealthy immigrants to Athens - which as a name still carried considerable prestige.

Democracy itself, however, buckled under the strain. Persuasive speakers who seemed to offer solutions - such as Demosthenes - came to the fore but ultimately took it closer to military defeat and submission to Macedonia. Critically, the emphasis on "people power" saw a revolving door of political leaders impeached, exiled and even executed as the inconstant international climate forced a tetchy political assembly into multiple changes in policy direction.

Well. I hear Cassandra's voice again. But rather than make pessimistic predictions about the future of our governmental institutions, two questions have been foremost in my mind as I look ahead, concerning things over which I actually have some control:

First,"What can I do to make people less afraid?" and second, "How can I give hope?"

We're living in an Age of Anxiety. Some of the causes are absolutely real, and some are greatly exaggerated. Our fears and anxieties are fueled by the media of all kinds, and, as a result, these emotions keep a great many people in a perpetual state of helplessness and despair. It's easy to forget that we all have choices about how much we expose ourselves to the relentless bad news and anxiety-mongering in the mainstream media, and the fraught (or utterly superficial) conversations on social media. Real life still exists, with all of its joys, sorrows, and fascinations, and its persistent call to us to engage fully, and live fully.

I think it's incumbent on all of us in any sort of leadership position to confront, understand, and manage our own anxiety, or we cannot be effective leaders for positive change, so that is one place to start. We need to form groups, both informal and formal, for discussion and action toward positive change in our institutions and communities -- the places where we can make a difference. When we are actually doing something, instead feeling helpless, isolated, and afraid, life begins again, creativity begins again, renewal happens, hope is created, and people are attracted to join us.

And surely, there is a lot that urgently needs to be done and can be done by ordinary people, without the aid or interference of governments.

When I was traveling in Greece, I kept overhearing people at ancient sites saying things like, "Well, my friend likes this, but to me, it's just a pile of rocks," while others were avidly exploring and trying to understand what they were seeing. Life is always like that, I think. We can look out at the ancient agora -- real or metaphoric -- and see ruins built by dead people that are a mere backdrop for yet another selfie, or we can use our imaginations and see beauty, lessons from the past, and potential for the future, which is -- I am quite certain -- the desired legacy of the thinkers and creative people of previous, equally fraught times, who were human beings very much like ourselves.

What inspires you? What fills you with awe? What do you want to see preserved for the future? Where can you give hope, or lend a hand? Where do you need hope and encouragement yourself? How can we help each other in the coming year?

December 26, 2019

Books of 2019: eclectic as usual

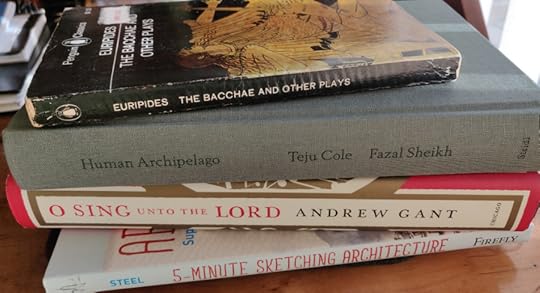

Boxing Day. Traditionally, this has been a day of curling up on the couch with a new Christmas book, but for the first time I can remember, I didn't receive a single one! I wonder if this is a trend among readers of this blog too. We don't buy or receive as many physical books, and maybe our friends and families are less likely to give them to us. I wonder, and, as a publisher, I worry. No matter -- trends haven't affected my reading patterns very much, except for the change to reading e-books borrowed from the Overdrive service at my library, or purchased on Kindle. I read almost exclusively on my phone, unless I've borrowed a physical book from the library. And though I did buy myself a couple of books about Greece that haven't arrived yet, I'm trying not to acquire too many these days -- the shelves are already overburdened. But read, I do.

I don't have a great deal to say about the books I read this year... there's a definite focus on Portuguese literature, because of traveling there and trying to write about it subsequently (a still-unfinished project). As usual, there are some classics from both ancient literature and the 19th and 20th centuries. After a debate with a friend about "the greatest novels" I decided to reread some of the candidates. Middlemarch was a first-timer for me, and I liked it. War and Peace was a re-reading, but while I had remembered the characters and basic plot, the book affected and impressed me much more now than when I read it before as a much younger person with so much less experience of life -- I think it deserves its status as one of the greatest novels ever written. I finally made it through Ulysses a few years ago, and don't plan to re-read The Brothers Karmazov, Anna Karenina, or Madame Bovary any time soon; other candidates are lined up for re-reading next year: The Magic Mountain, Moby Dick, The Sound and the Fury. But I find I'm more interested in continuing to read books in translation from world literatures that are less known to me. In addition to War and Peace, the "biggest read" was Lawrence Durrell's Alexandria Quartet, about the city where my mother-in-law spent her youth after leaving Armenia -- a city whose history is virtually disappearing.

Particular favorites this year were Compass by Mathias Enard, and two books by friends: Immigrant, Montana, by Amitava Kumar, and Human Archipelago, by Fazal Skeikh and Teju Cole. Among the Lisbon books, I especially loved For Isabel: A Mandala, and Requiem: An Hallucination, both by Antonio Tabucchi, and A History of the Siege of Lisbon, by Jose Saramago. Helen Vendler's Seamus Heaney is brilliant and illuminating. I didn't think Pachinko was incredibly well-written, but it was such a great window into a diaspora I knew little about (Koreans living in Japan). Likewise, there's always a Murakami on my list: I liked Killing Commendatore a lot, but didn't think it was in the same league as, say, 1Q84. The Frolic of the Beasts, by Yukio Mishima, is an excellent, extremely disturbing novel by the great Japanese writer.

It might be worth mentioning (since I don't think I have before) that I also regularly read and highly recommend the Canadian (but international) literary magazine Brick. I'd love to have a piece in there someday -- I came close with one this year, according to a kind letter I received from one of their editors, and will try to submit something again in 2020.

Right now I've started Flights by Olga Tokarczuk -- original, unsettling and intriguing so far. I enjoyed Greek to Me, a love letter to Greece and the Greek language by New Yorker copy editor Mary Norris, especially because since our recent trip I've been studying modern Greek - half an hour each morning, along with half an hour of French in the afternoon. In her book, Norris mentions visiting the home of the late great travel writer Patrick Leigh Fermor in Kardamyli, Greece, on the Mani peninsula. We were nearby and fascinated by the stoic ruggedness and remoteness of that region, so I've ordered a couple of Fermor's books -- one about the Mani, and the other about northern Greece -- so that will be how 2020 is likely to start out.

Finally, it was a great pleasure to hear and meet one of my literary heroes, Michael Ondaatje, this year at a reading he gave in Montreal.

What about you? Please share your favorites, or entire book list if you keep one, in the comments! I always love hearing from fellow readers at this time of year, and wish you all a happy year of reading ahead!

Book List, 2019

Drink Time! In the Company of Patrick Leigh Fermor, Dolores Payás

Greek to Me, Mary Norris

Electric Light, Seamus Heaney

The History of the Siege of Lisbon, Jose Saramago

The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, Jose Saramago (rereading)

The Man Who Loved China, Simon Winchester (audiobook, dnf)

For Isabel: A Mandala, Antonio Tabucchi

The Lives of Things, Jose Saramago

Helen, Euripedes

The Women of Troy, Euripedes

Ion, Euripedes

Falling Upward, Richard Rohr

The Proper Study of Mankind, Isaiah Berlin (bits and pieces, mainly the essay on Tolstoy "The Hedgehog and the Fox")

War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy (rereading)

Human Archipelago, Fazal Skeikh and Teju Cole

Middlemarch, George Eliot

Pachinko, Min Jin Lee

The Frolic of the Beasts, Yukio Mishima

O Sing Unto the Lord: A History of English Church Music, Andrew Gant

4 3 2 1, Paul Auster (DNF)

Pereira Maintains, Antonio Tabucchi

Warlight, Michael Ondaatje (second reading, for book club)

Requiem: an Hallucination, Antonio Tabucchi

What is Not Yours is Not Yours, Helen Oyeyemi

The Tiny Journalist, Naomi Shihab Nye

The Lisbon Poets (anthology)

Five-Minute Sketching: Architecture, Liz Steel

The Book of the Red King, Marly Youmans

Seamus Heaney, Helen Vendler

The Alexandria Quartet, Lawrence Durrell (3rd and 4th books, Mountolive, Clea)

Killing Commendatore, Haruki Murakami

The Alexandria Quartet, Lawrence Durrell (First two books: Justine, Balthazar)

The Relic Master, Christopher Buckley (DNF)

Immigrant, Montana, Amitava Kumar

Compass, Mathias Enard

December 5, 2019

A Bronze-Age Path to Self-Discovery

The "Warrior Vase", 12th c. BC, is so famous that the building in which it was discovered at Mycenae is called "The House of the Warrior Vase." I was completely crazy about this object when I first studied it: it felt to me like a sketch of Agamemnon's actual warriors going off from Mycenae to fight at Troy, while a woman, at far left, raises her hand in farewell. Agamemnon and the Trojan War are considered legendary, but the archaeological evidence from both Mycenae and Troy indicate beyond a doubt that advanced societies lived there in the Bronze Age, at least 400 years before the Homeric epics were composed, ruled by kings of great wealth and power, who traded and were in contact with other city-states and cultures in the Aegean, Egypt and North Africa, and the Middle and Near East.

I had just turned nineteen when I took my first course in Greek art: it was called "Greece in the Bronze Age", and was taught by John Coleman at Cornell University. Since childhood, I had been captivated by the Iliad and Odyssey, the Greek gods and the myths: this felt like a way to get closer. I still remember the day when John brought shards of impossibly ancient pottery into the classroom, and the first one was passed into my hands. How do we describe those moments of wonder that quickly move into some sort of inexplicable connection, and a passionate longing to plunge in deeply? By the end of that semester, after being immersed in the early cultures of Mycenae and Tiryns, the Cyclades, and the Minoan civilization in Crete, I knew for sure that this was what I wanted to study, and changed my major from biology to classics, with a focus on archaeology and ancient Greek art.

Head from a marble statue from the Cyclades, 2800-2300 BC. This sculpture originally had painted eyes and red striations on the cheek. You can see where Brancusi found inspiration. I've always loved Cycladic art because of its elemental simplicity: this particular head was chosen by the museum as one of its featured objects.

It wasn't easy; I was already a semester behind the students who had declared their decision earlier, so I had to catch up in the Greek language classes, as well as qualifying in French and German, and fit the required courses and my chosen electives into the remaining two-and-a-half years. Nevertheless, it was of the best decisions I ever made. Even though, at the end, I didn't want to pursue the academic route and become a professor, what I learned during those years studying with John, his colleagues Will Cummer, Will Provine, and Andrew Ramage, and brilliant Greek professors like Pierro Pucci, Fred Ahl, and Michael Stokes, completely changed my life. I learned how to be a scholar and my writing improved a great deal; I gained confidence in my ability to think and to express those thoughts with clarity; my interest in history, literature, and human culture deepened; I became more disciplined, and more confident about my own ability as an artist, because John encouraged me to illustrate my papers and honors thesis. I discovered, through the Greeks, my own passion for graphic design, and the use of positive and negative space, that formed the basis for my own eventual career in that field.

Flying fish swimming among fish-eggs and sea sponges, 16th century BC -- a fresco from Phylakopi on the Cycladic island of Melos. I had never seen this fragment before, and was delighted by it.

A tiny Mycenaean hedgehog.

And a huge Mycenaean octopus, amid fragments of seaweed, clearly showing the influence of Minoan art, which this vase-artist must have seen. 16th c. BC.

Through a series of unfortunate political events, my own lack of experience in traveling alone, and limited money, I never made it to Greece when I was young, even though I won a scholarship for a summer of archaeology there. Though I was considering studying the conservation of antiquities, my life took a different turn. Over the years, I would visit the famous Greek and Roman art collections in New York, Boston, London, Paris, Rome, and Berlin, including the Greek vases I loved, but many of the Bronze Age treasures that had first captivated me remained as pictures in books, or memories from classroom slideshows. Unlike the Parthenon sculptures and many of the finest Greek vases and sculptures, which had been taken from Greece long before by wealthy collectors or government-sanctioned archaeology expeditions -- stolen is the correct word -- many of the primary Bronze Age objects had stayed there, some because they were discovered later, or perhaps because fewer people prized them, and partly because some of the archaeologists who discovered them, like Heinrich Schliemann, had insisted that they remain in Greece.

The so-called "mask of Agamemnon" - a lifesize gold death mask of an unidentified Mycenaean king discovered by Heinrich Schliemann; this is one of several such gold death masks that he found.

Just one of many cases of Mycenaean gold of astonishing workmanship and detail.

A few weeks ago, I finally got to see these objects and visit some of the places where they were found. As I stood in front of the cases of Mycenaean and Cycladic art in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, I felt the years collapse: once again I was that young woman, seeing these things for the first time, feeling my heart leap with delight and fascination. How grateful, and how fortunate I felt, to be there at last!

Late in that long day of museum-looking, I went back through the galleries and made the two drawings shown here. It wasn't because I thought that my drawings would have any more value or beauty than my photographs of the objects, nor because I wasn't sure if I'd ever come back to Athens -- I certainly hope to, but one never knows about the future. All drawings aren't done for the same reasons. In this case I wanted to take the time to do this, because choosing these particular objects out of so many, and standing in front of them with the intent focus that a drawing requires, felt like a ritual act imbued with personal significance. It was a testament to relationship: not only with the objects and their anonymous makers, but with myself over time. I wanted to honor that, and so I drew.

![IMG_20200212_101923[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1581594274i/28957248._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200212_105525[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1581594274i/28957249._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20200124_100111[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1580036071i/28844768._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20191203_174646[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1575632621i/28566946._SX540_.jpg)