Elizabeth Adams's Blog, page 24

November 27, 2019

Another view of the Athens Polytechnic, looking north

I did another drawing, this time in pen. It's 12" x 9", done with a Sailor fude-nib pen, and Noodler's Lexington Grey ink, in a Stillman & Birn Gamma series sketchbook.

Here's a close-up. As I wrote on Instagram yesterday, I'm tempted to add color to this drawing, but think I'll resist. I've got a good start on a suite of drawings of Athens and Greece in this style, and feel like I'm gradually getting better at capturing the feeling of a visually complicated cityscape. The perspective and scale are relatively accurate, without being "architectural drawings" - which is what I'm aiming for: a fairly loose, artistic sketch. There are good reasons to keep these as a group, and frankly we seldom see monochromatic drawings these days, so that's a good reason to do them. But maybe I'll also do some color ones separately. Any comments/preferences?

November 25, 2019

Athens: Anarchists and Antigone

The Polytechnic University of Athens, on a bright day.

The first apartment we stayed in was located north of the center of the city, near the National Museum of Archaeology and the Polytechnic University. Last year we stayed in a tiny room in a less-than-stellar hotel in the touristic center near the Acropolis - a great location, with good breakfasts, but we could barely turn around in either the bedroom or the bath, and we heard loud guests at every hour of the day or night. This time we wanted a larger, quieter place where we could cook, and learn about another part of the city. The apartment we rented turned out to be perfect. It was on the seventh floor, with a wide balcony that looked out over the buildings and courtyard of the Technical University, site of historic resistance by students against the military junta that ruled Greece between 1967 and 1974. On November 17, 1973, after several days of escalating student demonstrations, armed police crashed through the university gates with a tank. 24 civilians, including students and a young boy, were killed, and hundreds injured, though the official government inquiry disputed these deaths. Nevertheless, this catastrophe triggered events that led to the fall of the government the following July.

After that, a law was passed making university campuses safe zones, where the police cannot enter. The Polytechnic became the main site of resistance movements, and the home of the contemporary Greek anarchist movement. The neighborhood around the campus is called Exarchia, and is controlled by anarchist groups, but we didn't feel any threat from them -- rather than being against authority in all forms, their philosophy seems to be a bit more subtle: they're against the police, capitalism, globalization, and fascism, supportive of immigrants and refugees who they see as victims of capitalistic military actions and policies.

A poster in the neighborhood. The headline at the top reads "οχι αλλοι νεκροι, οχι αλλα στρατοπεδα συγκεντρωσης", "No more dead, no more concentration camps."

Our apartment host explained that the main university building was now occupied by students, and while the area was safe, she was glad we wouldn't be there on the 17th, because that was an annual day of demonstrations, when the anarchists and police always clashed, sometimes violently, with some danger from tear gas, Molotov cocktails and the like. While we were in residence, we watched the students coming and going, as well as faculty -- apparently classes were still going on in some of the other buildings. Graffiti, posters, and large homemade banners in a several-block radius indicated the presence of active resistance by these anarchists, with messages of solidarity with refugees and migrants -- of which Greece has a disproportionate number, many in controversial detention camps -- and anti-capitalist slogans. One weekend night, there was a demonstration that went on into the wee hours, with speeches followed by live music; we had a ringside seat, but couldn't tell what was really going on.

A pencil sketch from our balcony, looking toward the courtyard of the Archaeology Museum.

The buildings of the Polytechnic University are gorgeous examples of neo-classical architecture, designed by the architect Lysandros Kaftantzoglou (1811–1885) who would not be happy to see their current condition. From our balcony we looked down over the tiled roofs of two open, colonnaded buildings modeled after the classical stoa, or marketplace with columns, common to all public agoras in ancient times, and the beautifully-proportioned main building, with its pediment and Ionic columns flanked by staircases. Part of the roof of this building has fallen in. There's a courtyard and garden filled with flowering plants and trees, and, closer to the street, monuments to the fallen students as well as the remains of the gate that was smashed by the tank back in 1973.

Socrates (right) and Plato (left) presiding over the entrance to the Academy of Athens -- the name harkening back to Plato's Academy --which is the country's national academy and highest research institution, where work is divided into three orders: Natural Sciences, Letters and Arts, Moral and Political Sciences.

Anarchistic thought has a long history in Greece, going all the way back to Socrates, who, if not being an out-and-out anarchist in a modern sense, taught his students to continually question authority, and value above all one's right to a free will. He was tried and put to death because of his criticism of the political authority and direction of the Athenian state at the time. (As a political concept, Αναρχια, "anarchy," is a Greek word that first appears in plays by Aeschylus and Sophocles around the same time, in the fifth C. BC.)

A copy of Sophocles' Antigone in modern Greek that I bought in an Athenian used bookstore. I can read the Greek alphabet and had three years of university-level ancient Greek, but don't know the modern language at all. I can only decipher it with difficulty and the help of translation programs. I've forgotten most of the ancient Greek I once knew, but I thought I might compare this text to the original and learn something: intellectual folly, probably, but it was one of those things you see when traveling, and just want to have.

As one article I read pointed out, Sophocles' play Antigone is centered on the anarchist question of whether the young protagonist, Antigone, is right to exercise her free will against both family and the authorities -- to choose to properly bury her brother against the advice of her sister, and the express decree of the king, who has forbidden the burial because her brother had died fighting against that state.

Posters for (I think) current theater productions in Athens. Sophocles' Antigone on the left, a play titled The Building" on the right.

These are human questions that have persisted throughout recorded time. It's not surprising to me that this Greek play not only continues to be performed, 2500 years after it was written, but has also inspired a number of recent works, such as Kamila Shamsie's novel Home Fire, in which a young British woman rejects her sister's (and the state's) prohibitions by trying to aid, and then bury, her brother who left Britain to fight for ISIS, then regrets his decision and tries to return home. We still have a very difficult time deciding which is the highest "right": following the authority and wishes of one's family or one's country, or doing what an individual feels to be right and just, according to their own conscience or spiritual convictions, even if the penalty is ostracism, exile, or death. Jesus' difficult and hotly-debated parable in Luke 14:26, "If anyone comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters--yes, even their own life--such a person cannot be my disciple," speaks to much the same issue.

Here in Quebec, we also have a new film titled Antigone. The writer/director Sophie Deraspe said she was inspired by her reading of the play many years before, and by the story of Fredy Villaneuva, who was killed by a Montreal police officer in 2008 after an illegal game of dice in Henri-Bourassa park escalated into a physical confrontation with police. The film is about a girl in a Montreal refugee family whose brother is shot and killed by police. Against the wishes of her family, she tries to save her remaining brother, who has been arrested and faces deportation, and then runs afoul of the law herself.

Socrates would be right at home.

November 18, 2019

Return

A sketch of the Acropolis done at home, back in October, shown here in three stages. Drawn with a Sailor fude nib pen on toned paper, with some added gouache in the other two stages below.

Apologies for my long absence here -- I've just come back from 2 1/2 weeks in Greece, and the month before was a bit crazy because J. had a show for the launch of his new book two days before we left. I don't like to post much online when I'm away; maybe it's paranoia, but it doesn't seem smart to telegraph to the world that you're not at your home or workplace for an extended period. Anyway, we're back. On Friday it was 20 degrees Celsius in Athens. Today it's -4 C. here in Montreal, and there's snow and ice on the ground and sidewalks. We were forewarned, and to be honest, it wasn't that big a shock when we stepped out of the Trudeau airport terminal into air temperature and wind I could only describe as "bracing" and a complete change of seasons from when we left. As lifelong northerners, winter feels normal to us, and we had packed extra layers in case, so we opened our suitcases near the baggage counter (like a lot of other Montrealers were doing) pulled out the hats and gloves and parkas, and stepped off into home territory. Still, the next morning we couldn't help remarking about the bougainvillea and lantana that had been blooming around us the day before, or the taste of beautifully heavy, ripe tomatoes, or the oranges, limes and lemons just getting ripe on the trees that grow along Greek streets and in gardens. As I described to a friendly barista in a favorite Athenian cafe, in Canada it really is like the tale of Persephone, where she ate six pomegranate seeds in Hades and the earth was plunged into winter for as many months. At least, that's what how Roman writers like Ovid told the tale. For the earlier Greeks, Persephone's punishment for eating food in the underworld only required that she spend a third of the year there -- a more accurate reflection of Greek seasons. Winter, even in the mountains in Greece, doesn't seem to last much more than four months.

November is the time of the olive harvest, and of pruning and burning in vineyards and olive orchards. We also saw people pruning shrubs, like overgrown laurels, and pollarding their trees, especially in villages. Their fall has been unseasonably hot -- it was certainly cooler when we visited last year -- and everyone remarked on this. Last year there was snow on Mt Parnassus and skiers already on the slopes; this year people were still swimming in the sea. But further north in Europe and in northeastern North America, the cold has been much earlier than usual, and the storms more violent. When we passed through Paris on our way home, there was snow on the ground and our flight was delayed for de-icing. I don't see how anyone can possibly deny that climate change is real.

Last year we were in Athens for a shorter time, about a week, and drove through parts of northern Greece, visiting Meteora, Thessaloniki, Vergina, and Delphi before returning to Athens. This year we spent longer in the city, on both sides of a road trip to the Peloponnese: Napflio and Epidaurus, Mycenae, Sparta and Mystras, an amazing drive over the mountains through the Langada Pass to Kalamata, down into the remote Mani Peninsula, and then back past Tripoli and Corinth, stopping for a night on the sea at Kineta, and driving above the Gulf of Corinth to visit the Osios Lukas monastery and then drive past Thebes before heading back to Athens. Along the way we met and talked to a lot of different people, and while we had planned the basic shape of the trip beforehand, a lot happened that was unexpected, which is one reason why we like traveling this way. It was such an epic trip that in some ways it doesn't seem real. It's hard for me to process all that we saw and experienced, let alone formulate words to describe it -- which is also what happened last year: I started to try, and gave up.

But I did draw quite a lot, throughout the two and a half weeks, trying to keep to my goal of doing at least one drawing a day. The only sketch I did in color was the very first one, of a baked-goods and candy seller in Syntagma Square while J. was buying SIM cards for our phones. After that I switched from the toned paper sketchbook I had made, to my usual Stillman & Birn hardcover, and sketched in pencil or ink only. Whether these drawings will form the basis for other work now remains to be seen, but I'm happy that I was able to keep up the sketching practice, even sometimes in the car as we drove through changing landscapes, and to work quickly. I was very aware of being helped by all the drawing I've done in the past -- it's like playing scales on the piano; you do get better, and more confident about tackling difficult or complicated subjects. This awareness also helped to keep me from being discouraged by the inevitable, less-satisfactory drawings. It's all a process, and these are sketches after all: a very personal way for me to record places or experiences that, for various reasons, I wanted to remember as important. Sitting down with the sketchbook for half an hour in a place that has touched me is an experience in itself that is forever linked to that drawing -- I remember the calls of the birds, people's voices, the sound of the wind, the feeling of the earth or rock or bench on which I was sitting, what I was thinking as I worked.

After two trips to Greece and one each to Sicily, Lisbon, and Rome, I know that the Mediterranean, and Greece in particular, have gotten under my skin. Actually, I suspect that they touch something that was there all along, even from childhood. I'll be exploring that in more depth over the next weeks. For now, it's good to be home, and back with this far-flung community of online friends.

October 12, 2019

The Navel of the World

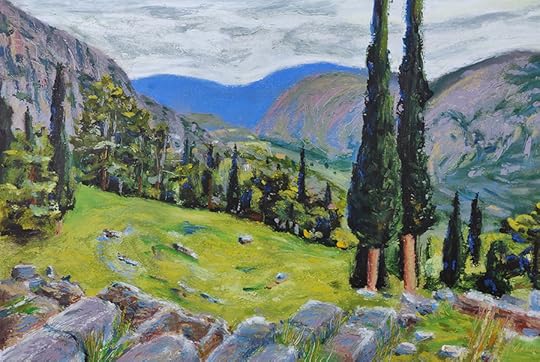

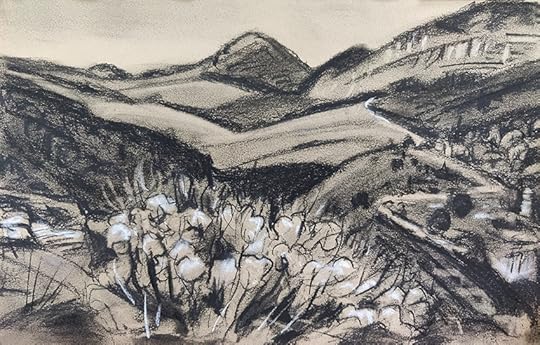

Some of you may remember that last winter I was working on a series of sketches of the landscape at Delphi, Greece. The one above remains my favorite - I even made it the screen image on my phone.

A few weeks ago I did another one, this time in oil pastel, following up on the oil pastels of Sicily. I thought maybe that medium would lend itself to this subject. Here's the full painting:

There's a lot that I like about it, and a lot I don't. My handling of the medium has gotten more confident. The color palette here works well, even though it's mostly imaginary. What doesn't work for me is the composition. It's fine for a "pretty painting" of a scene, but that's not what I'm after -- I've got photographs that serve that purpose. The circular, central lawn-like area is boring, and it makes the entire left side of the painting boring too, even though there are some interesting passages in the trees. Furthermore, the ruins in the foreground feel too literal and too prominent, even though I tried to subdue them. The result is that there are too many places for the eye to look, and this distracts from what drew me to this view in the first place. Why is it so hard to remember that, I wonder?

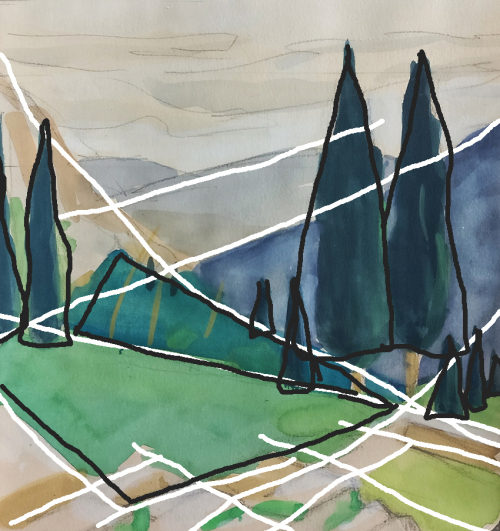

The picture is in this area:

Which is, not surprisingly, much like the gouache. Here it is again:

What makes this compositions work is the combination of strong simple shapes with intersecting angles that create tension and interest. In the gouache, which is really pared down to essentials, both in shape and in color, these elements create a locked-together composition of dark, slightly-triangular verticals held within the picture frame by the intersecting diagonals. Because the viewer isn't overwhelmed with details, and because the palette is so limited, the more abstract picture is able to create an emotional response that, for me anyway, is much closer to what I actually "felt" when standing there, and what I hoped to take away.

With the oil pastels and the picture cropped this way, I really like the strong cobalt blue with the lavender and dull green of the mountain. The foreground is missing in this crop, but the gouache helps me see better what to do with it. In addition to the beautiful, iconic trees, one of the most striking aspects of this landscape was the circular pattern of rocks and scrubby growth of the mountain behind the cedars. I like how the oil pastels have worked to capture that -- it's subtle, not detailed, but effective. Now I'm thinking about making a larger painting, in oils, based on what I've discovered by analyzing these pictures. The main message is simplify.

--

While I was working on this piece, I found a suite of poems by Seamus Heaney that he had written in Greece. One of them is set in Delphi, and it speaks of Heaney's desire to drink from the spring where all visitors to Delphi who came to consult the oracle stopped to wash and drink; the same spring was used by the Pythia and the priests for a ritual cleansing before giving an oracular pronouncement or interpreting an oracle.

The Greeks believed that the spring was located at the center of the earth. Zeus, king of the gods, had loosed two eagles from opposite ends of the world, and, flying at the same speed, they crossed paths above Delphi. Zeus let a stone fall from the air where they crossed, and where it fell became the sacred site, marked by a stone called the omphalos, or navel of the world. Under the omphalos was buried the mythological monster called Python, which had guarded the sacred spring, until it was killed by the god Apollo, to whom Delphi and the Oracle became sacred. We saw a Roman copy of this large carved stone in the museum in Delphi. The carved pattern represents a woolen net that was once thought to cover the stone.

If you've been to Delphi, you would have thought, as I did, what a long, difficult journey it must have been to get there from any of the major city-states of Greece, and then to have to add the arduous climb up the side of Mt Parnassus. I wish I had known that the spring still exists, and that there's a modern fountain by the side of the road for modern travelers, but I had no idea! Heaney, visiting in the 1960s, did know this, and of course -- as a poet who had been steeped in the Greek classics, translated some, and used so many references and stories in his own poems and plays -- he was determined to drink from it himself. The poem speaks of his frustration and its resolution, and it's an image that has now been added to my own thoughts about Delphi.

Castalian Spring

Thunderface. Not Zeus’s ire, but hers

Refusing entry, and mine mounting from it.

This one thing I had vowed: to drink the waters

Of the Castalian Spring, to arrogate

That much to myself and be the poet

Under the god Apollo’s giddy cliff—

But the inner water sanctum was roped off

When we arrived. Well then, to hell with that,

And to hell with all who’d stop me, thunderface!

So up the steps then, into the sandstone grottoes,

The seeps and dreeps, the shallow pools, the mosses,

Come from beyond, and come far, with this useless

Anger draining away, on terraces

Where I bowed and mouthed in sweetness and defiance.

--Seamus Heaney

October 5, 2019

Montreal Welcomes a Modern-Day Prophet

Text by Beth Adams, all photographs (c)2019 by Jonathan Sa'adah

I participated in the climate march last Friday, along with more than half a million other Montrealers. We had a good-sized contingent from Christ Church Anglican Cathedral, and we all met up there, and walked to the starting point together. My husband, who's a professional photographer, roamed around the route of the march, and ended up just behind the official press area at the stage where Greta Thunberg eventually spoke.

One of the young people who was marching with us said that this was her very first protest march - she grew up in the Midwestern U.S., and has just started graduate work at Montreal Diocesan Theological College. Several of us, who've already done this for a lifetime, talked to her about how she was feeling -- she was excited -- and she asked about the most recent, or most memorable, marches we'd gone to.

Students climb up the Sir George Etienne Cartier monument, for a good view at the start of the march.

There were a lot of great signs in both French and English -- I thought the large poster of Greta as Joan of Arc, in armor and dark bangs, was pretty clever, and very French, but certainly hope she doesn't meet such an awful fate.

Who could not be impressed, buoyed, and encouraged by the spirit of this preponderantly-youthful crowd, who seemed determined and mostly cheerful in spite of the dire warnings on their signs? But I noticed that the faces of many of the older people looked much more solemn: we know the stakes and the opponents now, we've been here before: against war, against nuclear power, against apartheid, for the rights of refugees, the rights of women, blacks, the disabled, those who are LGBTQ+. We're worried that this movement, as large as it is, and as absolutely right as it is, will have great difficulty prevailing over the forces arrayed against it. Nevertheless, it was a great day, and I was proud of my city and every person who had come out to march.

We had a long time to wait before getting started, and the crowd was enormous. I never made it to the end because I had another obligation, and my feet were killing me, so I bailed out in mid-afternoon and walked back home; Jonathan didn't get home for several more hours. In spite of the city making the metro free for the day, it was still very crowded, and some of the stations had been made entrance- or exit-only to try to alleviate the congestion. I was impressed, too, with the orderliness and camaraderie of the marchers, and the benign, friendly attitude of all the police. A day later, when my husband and I walked around the area where the march had ended, there was not a trace of debris or destruction from those 500,000+ people.

The Rev. Jesse Zink, Principal of the Montreal Diocesan Theological College, wrote an essay titled "Thus saith Greta", likening Greta Thunberg to an Old Testament prophet. That wasn't a comparison that had occurred to me, and it really struck hpme, especially when I saw the photographs Jonathan had taken. She stands alone and vulnerable, a child, looking even younger than her 16 years, and she yet she has the courage to speak truth to power. Rev. Zink writes:

"Like many other prophets throughout history, her ministry has imposed a cost on her: she has given up school, she has changed her life, she has been subject to accusation, slander, and attack...

In both her UN address and her Montreal speech, Thunberg leveled a straightforward generational challenge: 'You are failing us. But the young people are starting to understand your betrayal. The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And if you choose to fail us, I say: We will never forgive you.' One of the reasons climate change is such an intractable problem is precisely its inter-generational nature: the actions of one generation are largely felt in another..."

Zink speaks of the Biblical covenant between humans and God that Moses revealed as being specifically inter-generational -- in fact, "down to the thousandth generation" - in other words, forever. Other cultures and religions have similar stories that pass down the idea of stewardship for the earth to subsequent generations. Part of why human-caused climate change is so malevolent is that it violates this long inter-generational responsibility, and, I might add, destroys it in such a short period of time.

"As we discussed in the ministry seminar on Friday, the world needs prophets, evangelists, missionaries, and preachers. But we also noted that it needs priests, people who can gather the community and enable its gifts to be released. We saw that in Montreal on Friday in the relatively low-profile and anonymous group of people who provided the forum for a prophet of our time to preach her word."

In my lifetime, I don't think I've ever seen anyone quite like this young David going up against Goliath. Montreal is not a religious city any longer, but it is a principled and progressive international city where people think, and are willing to stand up for their beliefs. Last Friday, it felt like part of what the crowd was doing was holding Greta up with our bodies and our voices, giving her that forum in which to preach, and also giving her "our ears to hear." Each of us must find our own role in this crucial struggle, and we can't allow ourselves to be discouraged: it is her future, and the future of all the young and yet-to-be-born of our precious and fragile earth -- not just humans, but all living things -- that we are responsible for protecting.

September 18, 2019

A Beautiful Ending for the Summer

Our friend G. lives on a remote hillside in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, where he has a garden of breathtaking beauty. Once every summer we drive out to spend the afternoon and evening with him. This year it was a perfect day - sunny, and still warm enough to eat outside, though by the end of our meal we were all bundled up in jackets and shawls. Here's J. on the deck overlooking the garden and the hills beyond, under the grape arbor. We spent some time trying and failing to find G.'s new glasses which had fallen or gotten snagged somewhere in the garden when he was picking the bouquet for the table-- he found them himself a couple of days later -- and I sat on a rock overlooking the pond for a while, watching frogs floating lazily on the surface, legs splayed. Aren't they wonderful, G. said, and I told him I aspired to the zazen of a frog. Then we had snacks and wine, and later, a cooperative dinner of salmon, corn picked that morning, fresh green beans, salad, strawberries.

G. gave me the flowers to take home, and of course I had to sketch them the next day.

What is it about certain landscapes that gives them their particular emotional resonance and feeling? G.'s place always feels the same to me, regardless of the weather or time of year: it's one of the calmest, most quiet and peaceful places I know, and I always feel restored after being there. Some of that comes from the person who lives there, in an almost monastic lifestyle. It also comes from the way he has laid out the garden, with its stream and ponds, in the middle field, between the house and the distant mountains. Wherever you are, the garden beckons, and it is always present, like a symbolic home to which you can return but which also stays in one's memory, between the near and the far of our lives. It also contains a number of large standing rocks, and because I am tremendously fond of rocks, I revisit them each year almost like people with remembered individual personalities; I like laying my hand on them and feeling the retained warmth of the sun.

--

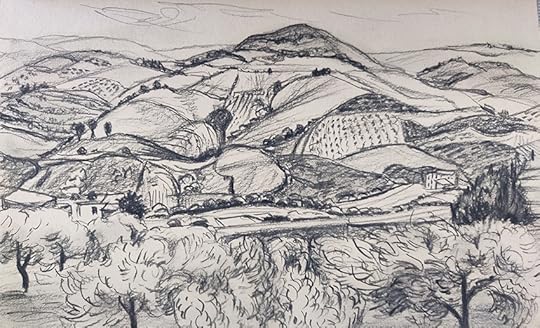

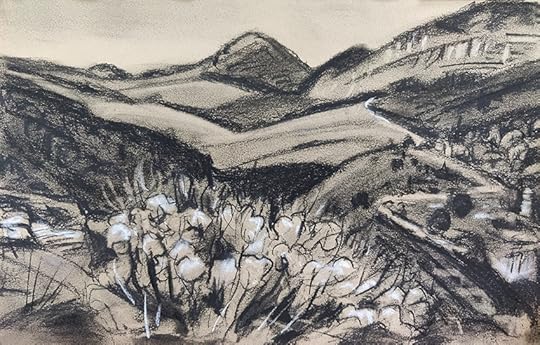

Last week I also returned to the Sicilian landscapes that have gotten so far under my skin, and did this drawing of hills and a patchwork of orchards and fields, seen from the top of the hill near the Greek theater at Segesta:

Olive trees and fields from Segesta. Charcoal on toned paper, 8.5" x 5".

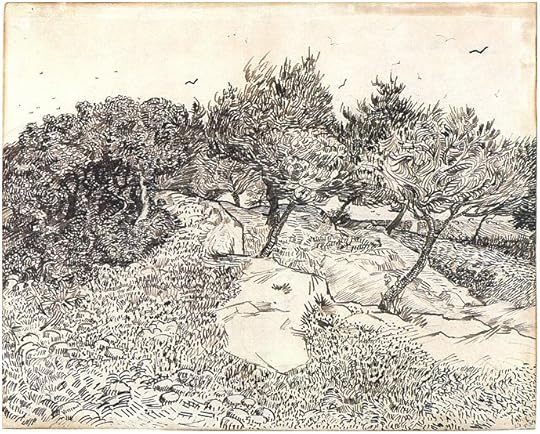

I've planned to paint this scene but wanted to draw it first. The pastoral landscape of olive trees and planted fields remind me of the subjects of some of Van Gogh's late drawings. As I work toward refining a style of my own for this sort of drawing, I look for the subject's internal rhythms and the ways the shapes interact. This is partly about finding patterns in the ways things grow or are arranged in the landscape, and partly --again -- something about the emotional temperature of the scene itself. I've always been astounded at how Van Gogh was able to convey these qualities of "IS-ness" as well as how he felt about particular places on particular days. Without imitating him, I hope to continue to work on my own language for doing something similar, because landscapes and the individual elements in them -- like trees or the pattern of an orchard -- do speak to me almost as people do. The drawing or painting thus becomes a portrait of the subject, and secondarily a portrait of the artist at a particular time of their life...

Vincent Van Gogh, Olive Trees, Montmajour, 1888.

September 11, 2019

In Memoriam

Photographer Robert Frank died yesterday at the age of 94.

Jennifer Lewis, artist, photographer, ceramicist, and one of our closest lifelong friends, died a year ago this week, at the age of 68; the day the photograph above was taken, we were together at the 2008 Robert Frank show at MoMA, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the publication of Franks' masterpiece, The Americans.

Aaron Moore, historian, professor, and husband of my dear friend Nilanjana Bhattacharjya, died on Sunday at the age of 47 -- just half that of Robert Frank.

I have no way to make sense of the unfairness of life, the time we're each allotted, or the way each of us meets our fate. What I do know is that each of these people used the time they had to be creative, to be productive and engaged, to connect with others, to try to make a difference, and to be courageous. Each of them touched me, in quite different ways, and I will always be aware of them and remember them.

Jonathan and Jenny looking at Robert Frank's contact sheets, New York City, 2008.

--

It's September 11th, a day of remembrance that goes beyond any one person. That morning, Jennifer called us in Vermont, from her roof in lower Manhattan: we were on the phone with her when the second plane hit the tower.

And on this day, I think, too, of what Robert Frank photographed in his iconic book, The Americans. Like Dave Heath, whose photographs we saw earlier this summer at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, like Jack Kerouac and Alan Ginsberg, all of whom knew each other, Frank was trying to express something tragic and destructive that he sensed at the heart of American life in the 1950s and early 60s -- something that would explode into violence later in the 1960s, and has never been resolved. Frank showed us America's racism, economic inequality and insensitivity, its feel-good culture, and above all, its denial. Now, much of the divisive toxicity that became an undercurrent after the 60s has been allowed, and encouraged, to boil over and come to the surface. So I think a post entitled In Memoriam today is also a requiem for an idea of America that is dying, and must die eventually -- but how long that will take, and at what cost, none of us can predict.

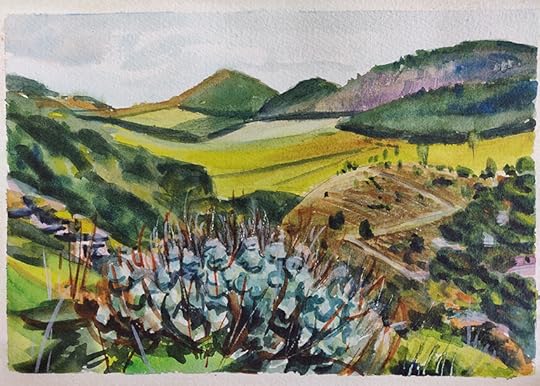

September 9, 2019

When black-and-white doesn't make it.

Here's a charcoal sketch of the view at Segesta, Sicily, that you see if you turn 90 degrees to the right from the angle in the previous post, the picture with the Artemesia bush. This direction looks into a deep gully, with areas of exposed rock that may have been a source for some of Segesta's ancient buildings. After two attempts, one in pencil and one in charcoal, I still felt that it was almost impossible to capture the essence of this landscape in black and white, so I thought I'd try a quick sketch in oil pastel. It ended up being more than a sketch, and I rather like the feeling of it. Here, the mountains came alive with both rocks and trees, the fields sparkled with color, and the abyss of the gully fell down and away.

View at Segesta. Oil pastel on paper, 9" x 6.5 ".

Here's a detail, close to life-size on my monitor, that shows a little better what the surface is like.

Oil pastels are an interesting medium. Using them is more like painting in oils, I think, than drawing in dry pastels, but with some of the qualities of both. They're also very messy - I was covered with sticky pigment by the end of this and so was my work surface. Fortunately, all Rembrandt oil pastels are non-toxic. They never really dry, though, so an oil pastel painting has to be presented behind glass.

The good thing for me is that it's almost impossible to get fussy or tight with them, because the sticks are soft, large, and blunt. You can layer and mix colors on the surface, and scratch through the paint to add some detail or texture, as I've done here, but you can't draw like you would with a small pointed tool. The palette I have is limited - about 45 colors - but that's OK for these purposes. And it's a good change from the demanding tension of watercolor.

--

Choir started again this Sunday, and it would be hard to express how glad I was to be singing again. During the summer, I'm glad of the break, but eventually I miss the music and the challenge of trying to do my best, and I miss my community of friends there. At our first rehearsal last Thursday, we sounded almost tentative to begin with, but quickly found our voices again. Yesterday's two services were very good, and it always feels like a miracle to me that with only fifteen or sixteen singers we can make as much sound as we do, or sing as subtly. This past weekend, Montreal celebrated "Les Journées du patrimoine religieux" so we had a steady stream of visitors through the doors, displays of historical photos and memorabilia, and volunteers on hand to give tours and answer questions. It also meant that we had quite a crowd of people for Evensong, which gives us a lift. This year we'll be experimenting with singing from the chancel steps so that we're not so far from the congregation as when we're up in the choir stalls or in the organ loft at the back of the church. The tricky thing is that this makes a physical separation from the organ when we do accompanied works, and there's a slight delay in the sound, so the organist has to watch the director in his monitor and play with the tempo he or she sees, which will be slightly ahead of the beat that is heard. Most listeners would not know this is going on, but it's a musical reality in many of the large cathedrals of the world.

The point of connection with painting is that in any art form, there are challenges, but also ways to overcome them!

--

This week I'm also remembering our friend Jenny, who died a year ago, and thinking of another friend whose husband died yesterday, while we were singing. He had been in difficult health for a long while, and in a crisis situation for two days, so it was not entirely unexpected, but it was still too sudden, and far too young. Suffering and death seem, at first, to be black and white, but in fact they aren't at all, because human lives are not monochromatic. We need to look at the difficult parts of life in all of their shades, not just in black and white, but in color too. Even an abyss has color and form in it, if we have the courage to look. Art, however, fixes a moment in time, while music always moves.

With its capacity to express such a wide range of human emotions, music is one of the best and only ways I can deal with death; I'm grateful for it always, but especially now.

September 1, 2019

More Sicilian Explorations, and a Watercolor Disaster

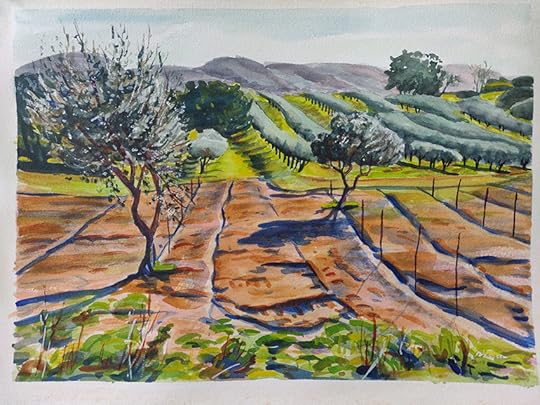

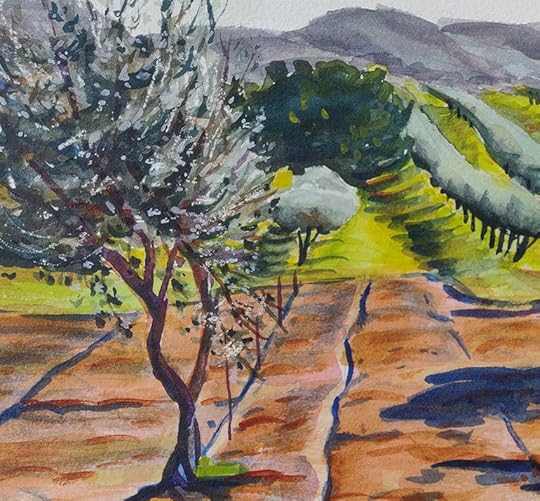

An Olive Orchard, central Sicily. Transparent watercolor on Arches cold press, 13" x 9".

Thank you to everyone who commented on the last post. I appreciated what you wrote very much, and it made me feel better to hear your solidarity and shared sorrow. One commenter, Robbie, said that he felt it was important to be informed and not turn away from the unpleasant facts -- and I agree with that very much. He also wrote: "I worry too about the exaltation I find as I delve into singing; might I be using music as a temporary insulation against a distinctly non-musical world?" My own answer is that we all need places of exaltation, because this is where we find the solace, strength, and --yes-- reasons for going on and continuing the fight for what matters. It's not insulation to spend time doing the things that make us feel the most human and join us with some of the best aspects of the human spirit throughout time, it's only insulation when that's ALL that we do. If I didn't make that clear before, I want to emphatically do so now.

One thing I try to remember is that there have always been stubborn people who have continued to do art, read and write books, make music, love and protect nature, cherish and guard all aspects of human culture, and take care of one another even when life felt the most hopeless. Often they have also been the same people who quietly sheltered refugees or the persecuted, visited prisoners, wrote underground tracts, participated in protests, smuggled food for people in need...the list goes on. These are not the people who get written about in history books, but let's try for a moment to imagine what would have happened if they had not existed. Where would we be? That's what is meant by action and contemplation as two sides of one coin. People who have found their own sources of strength and renewal -- what I like to call "wells" that we are able to go back to drink from again and again -- have more ability to see what needs to be done, and help others. So no, I don't think we need to feel guilty for spending time doing these things, not at all. We just need to try to see the whole picture, and move back and forth between the active and contemplative parts of our lives, keenly aware of what each is, and how they complement each other. As for me: our choir season starts this coming week, and I can't wait to be singing again -- for the joy and challenge it presents to me, for the community of other musicians, and for what it gives to the listeners who hear us each week. That music during the Sunday services seems more important than ever.

The painting of the olive orchard was done over two working sessions on two separate days. I'm trying for a more expressive use of color and brushwork, and it's not easy for me. Here, my original idea was to make the field (actually a very dull, uninteresting brown) a beautiful pinkish color, complementing the intense chartreuse of the grass in the orchard beyond. The shadows would be dark blue, violet, and dark green, with the painting unified by burnt orange and burnt sienna, as well as the silvery grey of the olive leaves. For a first attempt, I'm not unhappy with it, though I'd like it to be looser still. But I'm learning and progressing by pushing myself in this direction and thinking a lot about it. It would be easier in a different medium, too. A different approach might be to make the bare field violet or lavender, still complementary but toward the cool side of the spectrum rather than the warm. The feeling would be quite different -- less exuberant, but more harmonious with the silvery greens. Van Gogh and Gauguin are both great sources of inspiration for color ideas.

--

The painting at the top is the most recent. Earlier in the week I went back to the charcoal sketch from the previous post...

and made a color version of the same scene.

Artemisia bush at Segesta. Transparent watercolor on Arches cold press, 9.5 x 6.5".

I subsequently ruined this painting by running the top of it under the tap to tone down the contrast a bit, and then overworking it -- so this is my only record of it. But that's OK. If you're lucky, each watercolor painting has passages that are especially successful, or where something unexpectedly interesting (or disastrous!) happens. We can learn from these for the next one. I quite like the artemisia bush in the foreground - it retains some of the freedom of the original charcoal sketch. In hindsight, more problematic here were the brown hill and dark green vegetation at center right -- too much detail that competes with the foreground. You can see what I mean if you cover up that area with your hand. Before the rest got ruined, I washed over the brown with green, and it was much better. The strong color of the fields and the purple hill at the top, though, are important, and when I rinsed the paper, I lost that brilliance.

It was simply an error in judgement, and sometimes that can be the result of a mood, or an impulsive idea that isn't well-considered. In watercolor, unfortunately, those errors are usually fatal. I think it's important to share some of these problems here so you know they happen all the time!

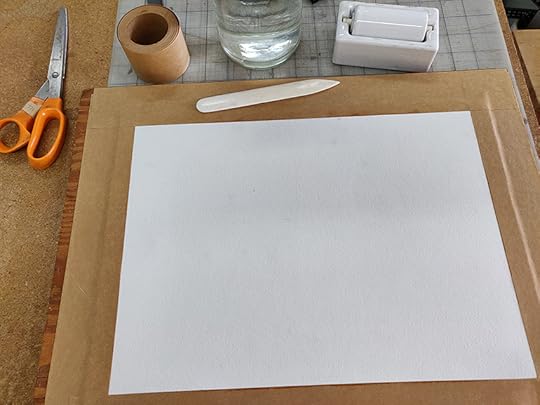

Here's my studio working method for stretching watercolor paper. This is the traditional way that my mother taught me when I was young, using gummed, water-activated kraft tape that you must moisten and then attach to the sides of high-quality paper (in this case, Arches or Fabriano 140# cold press paper) that's been soaked for at least 15 minutes, and then laid on a block of plywood. It's fussy but really works to keep that paper from buckling no matter how wet it gets, and is so much cheaper than buying pre-made watercolor blocks, or extra-heavy watercolor sheets. To remove the tape when the painting is finished, you need to carefully moisten the kraft paper backing, without getting any water on the painting itself (I use a small sea sponge soaked in water and then partially wrung out) and then the tape will release. Sometimes it's necessary to use a single-edged razor blade to remove bits of tape residue from the margins. For working outdoors or when traveling, watercolor blocks are indispensable, and I always have several of different sizes on hand, as well as sketchbooks. For the moment, it's helping me a lot to work in a larger format, mostly 22" x 30" sheets cut in quarters and then stretched with 3/4" margins.

August 23, 2019

Nonviolence

Artemisia Bush at Segesta, Sicily. Charcoal on toned paper, 8.5" x 5.5".

I'm drawing: small charcoals that would like to become big ones. This work feels like my bastion against what's going on in the world: this week we've heard about an Icelandic funeral for their first glacier to disappear; the forest fires in Brazil, devastating the rain forest, the lungs of our planet; and the insulting suggestion of buying Greenland, which may in fact be exploited in the future by the U.S. or Russia. The heat and the extreme weather in many parts of the world this summer are part of all of this.

But underpinning these catastrophes are the male aggressiveness, bravado, greed, competitiveness, and desire for domination at all costs that have driven our world since the beginning. I feel like I've been in mourning all summer. In July I re-read Tolstoy's War and Peace, in which he despairs about the human carnage and destruction caused by the Napoleonic wars, showing us, through masterful depictions of human lives, how characters of differing personalities deal with being caught up in war. I followed that with Isaiah Berlin's famous essay on Tolstoy's theories of history, "The Hedgehog and the Fox." I've also been thinking deeply about the Iliad, and Susan Sontag's essay about it titled "The Poem of Force," as I draw and paint places where the ancient Greeks once lived. My thoughts are starting to coalesce.

Where do we find freedom in such a world? And by freedom I also mean fearlessness. Is it even possible? I think we must begin by sitting in silence, developing our own inner life, and sharing thoughts with a few friends.

The problem is both macro and micro, both "out there" and personal, both structural and more amorphous and insidious: it is the very air we breathe. Every day we hear bullying language and hate speech from the most powerful leaders and from right-wing media; we see women who disagree -- from the strong women in Congress to activist Greta Thunberg -- castigated, ridiculed and attacked to the point of suggesting they should be maimed or even die. There's an increase in aggressive rhetoric not just from the right, but from the left. And it affects all of us.

Because, like prisoners in concentration camps, or victims of torture, we are, in fact, imprisoned and tortured by forces that we cannot control. It is natural to want to fight back, to fight aggression against oneself by being more aggressive, more self-protective, more tribal, but this is not and has never been the solution. Neither is it a solution to anesthetize ourselves through alcohol and drugs, consumerism, online games or social media, or escape by going about our lives as if nothing is happening. The most sensitive and thoughtful people among us see what is happening, and have seen it for some time. I am not talking about naive liberals who think that electing a woman is going to turn everything around, or that by eliminating plastic from our kitchens we're making any significant difference -- not that we shouldn't all make that effort. As Tolstoy pointed out about Napoleon and, to a lesser extent, the Tsar, one single man, no matter how charismatic or powerful, cannot gain that power unless he taps into broad undercurrents of belief already present in the population. The systemic violence, greed, racism, misogyny, homophobia, and exploitation that feed everything from war to genocide to climate change run very deeply and broadly; what Walter Wink called "The Powers and Principalities" have been operating since human societies began. By and large these systems have been dominated by white males who have believed in their right to supremacy over people of all other races, as well as over women. Even today, with all of our progress, women of every race are still below men in nearly every measure except life expectancy. And even the most intelligent and well-educated of us are often in positions where, to help families and institutions function, or in order to have some influence, we end up serving the men who actually hold the power.

I'm trying to think it through as a woman, and yet transcend anger, bitterness, frustration, feelings of impotence, to see how these violences and constraints could perhaps be gifts that can make me (and members of other marginalized/dis-empowered groups, as well as all people) actually freer than those who are caught up in turning the wheels of domination.

In order to do that, I see that I have to get off the wheel myself. One example: being largely off social media this summer has thrown what's going on there into sharp relief; I see it much more clearly. I have limited my consumption of news to a brief read of The Guardian and the front page of The New York Times every day. I don't watch television, but I've been reading widely, and choosing what I read carefully. I'm trying to get back into a practice of daily meditation and mindfulness in order to deal with my anger as well as my grief about what is happening to the natural world and our socio/political systems. I'm assessing all the ways I have been giving too much and allowing myself to be used, and considering how to be more effective with the energy, abilities, and yes, privileges, that I have.

Stepping away from time to time is part of the practice of nonviolence, which is made up of two sides of one coin: Action, and Contemplation. As Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Desmond Tutu, Jesus and many others practitioners of nonviolence have taught us, these are not dualisms, but integral parts of one continuous whole; neither can exist without the other. For me, the contemplative practices of art, music, journaling and being in nature are part of this path, and so is silent meditation, especially in a world that has become cacophonous to the point of damaging our very ability to speak effectively to one another or listen to what is said. On the other side of the coin is Action, but action (of which speech is a part) must proceed from a centered, calm, free, and deeply considered place in order to have any power against the forces that threaten everything we hold dear.

![IMG_20191126_131611[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1574952354i/28524172._SX540_.jpg)

![IMG_20191126_131611[2]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1574952354i/28524173._SX540_.jpg)

![15713383901732[878]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1574165378i/28475536._SX540_.jpg)